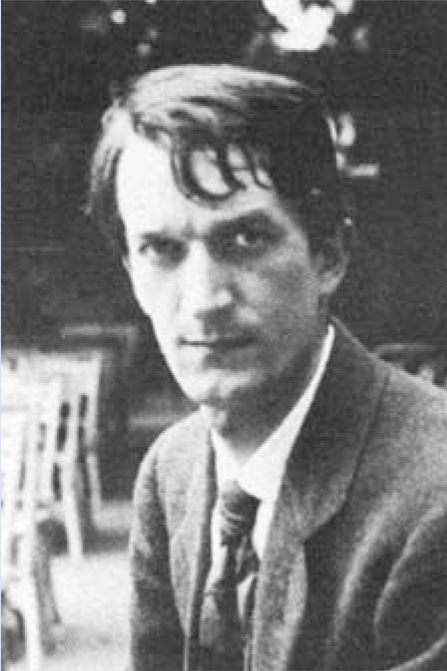

Rembrandt Bugatti was born in Milan in 1884. His family belonged to Italy's artistic nobility, and his conspicuous first name was given to him by his uncle, the notable painter Giovanni Segantini.

Among the family's friends was Russian sculptor Prince Paolo Troubetzkoy, who introduced young Bugatti to the particulars of plasticine sculpture; the Prince also shared his enthusiasm for the animal world, with its grand diversity of species providing excellent fodder for a visual artist. When Bugatti was in his teens, his family relocated to Paris, where he met gallery owner Adrian Hebrard, who commissioned and exhibited the budding sculptor's early bronze offerings. Still under Prince Troubetzkoy's influence, Bugatti began frequenting the wildlife sanctuary at Paris’ Jardin de Plantes, where he closely observed the fauna's kaleidoscopic array of physical and behavioural traits. Having immersed himself in animal study and refined his artistic talents, Bugatti moved to Antwerp, where he sculpted such works as the ‘Sacred Hamadryas Baboon’. Additionally, his rendition of a silver elephant was appropriated by his elder brother, Eltore, when he became a renowned manufacturer of the coveted Bugatti Royale.

Despite his promising artistic career, Rembrandt Bugatti contended with bouts of depression; he found some alleviation in his sculptures; his other solace was found at the Antwerp Zoo, home to a vibrant and glorious gathering of lions, panthers, and his especially beloved elephants. In these formidably colossal creatures, the artist saw the best of human qualities – maternal care, fraternal revelry, and communal cooperation. He endeavoured to convey these qualities in sculptures suggestive of immense potential energy; yet he lamented that there was only so much a still art form could depict of the wondrous elephantine movements.

However, Bugatti's lament over a fundamentally artistic problem would pale in comparison to the ensuing heartbreak found with the arrival of World War I. The outside world had fallen into chaos. Those denizens of the Antwerp Zoo – glorious as they may have been – were ultimately just beasts; amidst the massive slaughter of humans, only the slightest of concern could remain for these animals, who were expunged by zookeepers in a collective ‘mercy killing’. The animals were victims of a conflict they could never begin to comprehend. As for Bugatti, he understood all too well. The latest in warfare technology had made a grand debut. With mustard gas, tanks, and industrial-sized casualties, there were far greater issues at hand than the artist's microcosmic suffering over dead animals.

But the artist was suffering indeed; Bugatti's depression returned with a vengeance; the landscape of his psyche would grow as bleak as the wartime European landscape, and ultimately as deadly; he died by suicide in 1916, at the age of 31.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.