There has been a growing policy focus on young people's mental health. Three-quarters of lifetime mental illness are first experienced in adolescence, making prevention efforts in the first two decades vital.1 There are also stark sociodemographic differences in adolescent mental health difficulties,2 with far-reaching consequences for widening inequalities and adverse social, economic and health outcomes throughout life.Reference Clayborne, Varin and Colman3 Prevalence estimates from the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) indicated that almost 16% of 14-year olds reported high levels of depressive symptoms, and 15.7% reported self-harming.Reference Patalay and Gage4 Estimates from the 2017 Mental Health of Children and Young People in England Study, the only other source of nationally generalisable prevalence rates, reported that 16.9% of 17- to 19-year-olds had a diagnosable mental disorder.2

In this paper, focusing on mental ill health at age 17 in the MCS, we present the prevalence of high psychological distress in the past 30 days, 12-month prevalence of self-harm and lifetime prevalence of attempted suicide. We delineate inequalities in these mental ill health outcomes by gender, ethnicity, sexuality and socioeconomic position.

Method

Participants

Participants are from the age 17 sweep of the MCS (2018–19), a UK birth cohort study of individuals born at the start of the millennium. At age 17, 10 625 families participated, of whom 10 345 completed the self-report survey, with 10 103 completing a mental health measure, these are our analysis sample (mean age: 17.18, s.d. = 0.34, 51.3% female, 80.9% White, 3% mixed race, 10.9% Asian, 3.6% Black and 1.6% other ethnicities; 26.7% in poverty). In total, 10.6% identified as non-heterosexual at age 17 (6.5% bisexual, 2.5% gay or lesbian and 1.6% other). (Details of the study design, variables and attrition can be found at5).

Ethics approval for the age 17 sweep were obtained from the National Research Ethics Service Research Ethics Committee (REC) North East – York (REC ref: 17/NE/0341). Participants provided informed consent before completing the assessments.

Measures

Psychological distress

Participants responded to the K6 measure of psychological distress.Reference Kessler, Green, Gruber, Sampson, Bromet and Cuitan6 It asks respondents how often in the past 30 days they felt, for example hopeless, with five response options ranging from none of the time to all of the time. Total scores range from 0 to 24, higher scores indicating greater distress. The scale has moderate and severe thresholds, and we use the severe threshold (≥13) considered indicative of serious mental illness,Reference Kessler, Green, Gruber, Sampson, Bromet and Cuitan6,Reference Prochaska, Sung, Max, Shi and Ong7 hereafter referred to as ‘high psychological distress’.

Self-harm

Self-harm was reported in response (yes or no) to the question ‘During the last year, have you hurt yourself on purpose in any of the following ways?: cut or stabbed, burned, bruised or pinched, overdose, pulled out hair, other.’

Attempted suicide

Attempted suicide was reported in response to ‘Have you ever hurt yourself on purpose in an attempt to end your life?’ and coded yes or no.

Inequality indicators

Gender was recorded at birth. Ethnicity was parent-reported in childhood. Sexual identity was self-reported at age 17. Socioeconomic position was based on household income at age 14 that was Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development equivalised and categorised into quintiles; poverty status is based on having below 60% of median income.

Analysis

Prevalences have been weighted to account for both the complex survey design and non-response to follow-up, to generate nationally representative estimates. Details of loss-to-follow-up, data access, analysis software and code are presented in the Supplementary material available at https://doi.org10.1192/bjp.2020.258.

Results

The overall prevalence of high psychological distress was 16.1% (95% CI 14.7–17.7), 12-month prevalence of self-harm was 24.1% (95% CI 22.6–25.7) and lifetime prevalence of attempted suicides was 7.4% (95% CI 6.6–8.3%).

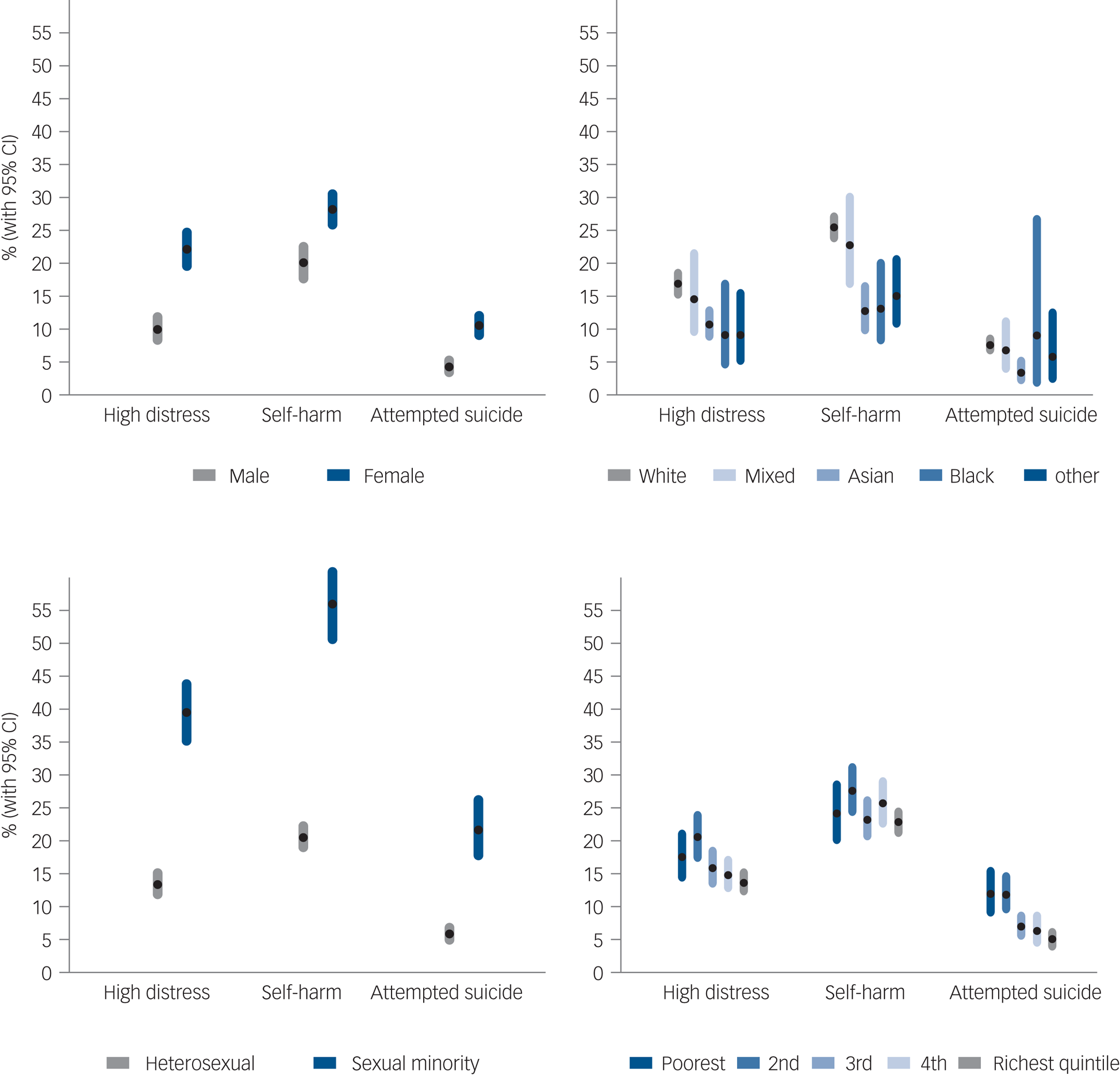

Figure 1 includes prevalences of high psychological distress, self-harm and attempted suicide by gender, ethnicity, sexuality and socioeconomic status (Supplementary Fig. 1 shows distributions of psychological distress by these factors).

Fig. 1 National prevalence estimates of high psychological distress (K-6 score ≥13), 12-month prevalence of self-harm and lifetime prevalence of self-harm with suicidal intent (attempted suicide) by (a) gender, (b) ethnicity, (c) sexuality and (d) income at age 17 years in the UK Millennium Cohort Study.

Females reported higher average psychological distress, with 22% experiencing high psychological distress compared with 10% of males. Females also reported higher levels of self-harm (28%) and attempted suicide (10.6%) than males (20% and 4.3%, respectively). Supplementary Fig. 2 shows types of self-harming behaviour by gender.

High psychological distress and self-harm were most prevalent in White respondents (Fig. 1). Attempted suicide rates were similar across most ethnic groups, with the lowest prevalence reported by Asian adolescents.

Large disparities were observed by sexuality with over half of sexual minorities having reported self-harming (55.8%) and about one-fifth (21.7%) attempted suicide (compared with 20.5% and 5.8%, respectively, in heterosexual adolescents).

Prevalences of high psychological distress and suicide attempts demonstrated a socioeconomic pattern, with some evidence of an income gradient, especially in attempted suicide where rates in the two poorest income quintiles are twice (around 12%) that for adolescents from higher-income families (around 6%). Self-harming behaviour is not patterned by family income, being similar across income quintiles.

Discussion

This paper highlights: (a) high prevalences of psychological distress, self-harm and attempted suicide among 17-year olds, and (b) gender-, ethnic-, socioeconomic- and sexuality-based inequalities in who experiences these difficulties at this age.

High prevalences have also been recently reported elsewhere with 15.4% of 17- to 19-year-olds having reported ever self-harming or attempted suicide.2 In contrast, lifetime self-harm prevalence in the UK adults was 6%Reference McManus, Gunnell, Cooper, Bebbington, Howard and Brugha8 and high psychological distress based on the K-6 in US adults was, for instance, 8.6%.Reference Prochaska, Sung, Max, Shi and Ong7

Our findings reflect well-established higher prevalences in females. However, the male–female gap in self-harm at age 17 (males 20.1%, females 28.2%) was considerably narrower than at earlier ages (males 8.5%, females 22.8%),Reference Patalay and Gage4 highlighting the greater increase in self-harming in males between ages 14 and 17.

Ethnic differences were similar to those reported elsewhere for this generation whereby White adolescents report the highest levels of distress.2 An exception is attempted suicide, which demonstrated few ethnic differences. The reasons for observed ethnic differences in distress and self-harm and the lack of ethnic differences in attempted suicide might include inequalities in support and access to services in ethnic minority groups.Reference Edbrooke-Childs and Patalay9

Sexual minority adolescents report the highest prevalences, with around 2–4 times the rates of self-harm and attempted suicide compared with their heterosexual peers. These findings highlight the need to better support this group and for parents, educators and clinicians to be aware that sexual minority adolescents might be struggling and need appropriate support, as they often also experience greater bullying, assault and a host of adverse co-occurring mental health related outcomes.Reference Amos, Manalastas, White, Bos and Patalay10

The distribution of psychological distress scores (Supplementary Fig. 1) highlighted that although the mean scores in the socioeconomically disadvantaged group are higher, they are also more dispersed, with more disadvantaged adolescents reporting both higher and lower distress. Of note, prevalence of attempted suicide was almost double (around 12%) in the poorest two quintiles compared with the other income groups.

Like all longitudinal cohorts, MCS suffers from non-random attrition, and although this is accounted for by weights in analyses it is possible that the loss-to-follow-up of more disadvantaged participants might result in underestimation of prevalences. At age 14, the symptom measure included was different, precluding making any direct comparisons in distress prevalences between ages 14 and 17.

Age 17 marks an important age before many key life transitions, including the ending of compulsory education and moving away from home. With the ending of support from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) around this critical age, many young people fall through the gaps between CAMHS and adult mental health services, potentially further worsening outcomes at the precise time when support is most required.Reference Singh, Paul, Ford, Kramer, Weaver and McLaren11 These findings underline the urgent mental health support need in this generation. On the cusp of adulthood, they warn of a further widening in health, economic and social inequalities.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.258

Data availability

The Millennium Cohort Study data are available to all researchers, free of cost from the UK Data Service (https://www.ukdataservice.ac.uk).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the cooperation of the Millennium Cohort Study families who voluntarily participate in the study. We thank the Economic and Social Research Council and the co-funding by a consortium of UK government departments for funding the MCS through the Centre for Longitudinal Studies (CLS) at the UCL Institute of Social Research. We would also like to thank a large number of stakeholders from academic, policymaker and funder communities and colleagues at CLS involved in data collection and management. The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of this report.

Author contributions

P.P. and E.F. conceptualised the study and interpreted the data. P.P. conducted the analysis and drafted the manuscript. Both authors approved the final version and consented to its publication.

Funding

The Millennium Cohort Study is primarily funded by the Economic and Social Research Council with co-funding from a consortium of government departments.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.