The question of whether gender identity disorder, also known as transsexualism, goes hand in hand with psychiatric problems has been investigated in a number of studies. Reference Verschoor and Poortinga1-Reference Bodlund, Kullgren, Sundbom and Hojerback10 Still, the relationship between psychiatric morbidity and transsexualism remains a hot topic for researchers. Furthermore, the classification of gender identity disorder or transsexualism in the forthcoming DSM-5 and ICD-11 as a mental disorder is being questioned. Reference Meyer-Bahlburg11 The aetiology of gender identity disorder also remains unclear. The relationship between this disorder and psychiatric morbidity is of great clinical importance, as follow-up studies have demonstrated that psychiatric comorbidity is one of the major negative prognostic features for the outcome of gender reassignment surgery. Reference De Cuypere and Vercruysse12,Reference Dhejne, Lichtenstein, Boman, Johansson, Langstrom and Landen13 Furthermore, debate on whether psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial dysfunctioning are a consequence rather than a cause of gender identity disorder is ongoing. However, research shows contradictory findings concerning the prevalence of coexisting psychiatric problems. Some studies of psychological functioning of individuals with gender identity disorder report a high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidity, Reference Verschoor and Poortinga1-Reference Hepp, Kraemer, Schnyder, Miller and Delsignore4 whereas other studies show results comparable with the general population. Reference Cole, O'Boyle, Emory and Meyer5-Reference Hoshiai, Matsumoto, Sato, Ohnishi, Okabe and Kishimoto8 Furthermore, differences in psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial functioning have been described between people depending on the direction of their gender reassignment (male to female v. female to male), and between individuals with early (pre-pubertal) onset and late (post-pubertal) onset gender identity disorder; most studies found more psychological problems in male to female reassignment, Reference De Cuypere, Jannes and Rubens2,Reference Gomez-Gil, Trilla, Salamero, Godas and Valdes7-Reference Landen, Walinder and Lundstrom9 whereas Bodlund et al reported more personality disorders in people who had undergone female to male procedures. Reference Bodlund, Kullgren, Sundbom and Hojerback10 Although there is no single, generally accepted definition of early- and late-onset transsexual development as yet, Reference Nieder, Herff, Cerwenka, Preuss, Cohen-Kettenis and De14 some studies have found that people with late-onset transsexualism showed more psychiatric problems than those with early-onset transsexualism. Reference Smith, van, Kuiper and Cohen-Kettenis15

The contradictory findings of the aforementioned studies are due partially to methodological differences, different ways of collecting data and differences in chosen instruments. Moreover, some studies suffer from serious flaws such as selection bias. As long as 30 years ago, Lothstein criticised the lack of systematic assessment and objective data collection. Reference Lothstein16 During recent decades the quality of research on gender identity disorder has improved substantially, resulting in larger and more reliable data-sets; nevertheless, large, prospective multicentre European studies with systematic data collection are still lacking. Our study is intended to fill this gap as part of the European Network for the Investigation of Gender Incongruence (ENIGI), an international collaboration initiated to set up diagnostic protocols and assessment batteries. Reference Kreukels, Haraldsen, De Cuypere, Richter-Appelt, Gijs and Cohen-Kettenis17 The major aim of our study was to investigate the prevalence of psychiatric problems in individuals with gender identity disorder seeking gender reassignment therapy. We compared different groups in terms of direction of gender reassignment, time of onset, comparison with the general population and clinic attended.

Method

Four countries participate in the ENIGI network: The Netherlands, Belgium, Germany and Norway. Reference Kreukels, Haraldsen, De Cuypere, Richter-Appelt, Gijs and Cohen-Kettenis17 Data were collected in Amsterdam, Ghent, Hamburg and Oslo between January 2007 and October 2010. The study was approved by the local ethics committees.

Participants

Adults seeking gender reassignment therapy and surgery at the four gender clinics were asked to participate. Patients were excluded from the study if they were experiencing psychosis at the time of assessment, were under 17 years old or had insufficient command of the language of the country in which they lived. Both self-administered questionnaires and clinical interviews were used in all gender identity clinics. All data were collected within the first 6 months of the diagnostic phase. All clinicians involved were trained psychologists or psychiatrists with experience in the field of gender identity disorder.

Measures

Gender identity disorder

Clinicians used a self-constructed scoring sheet with 23 items based on the DSM-IV-TR symptoms and diagnostic criteria for gender identity disorder and gender identity disorder in childhood (see the online supplement to this paper). Reference Paap, Kreukels, Cohen-Kettenis, Richter-Appelt, De and Haraldsen18,19 These items consisted of a combination of a symptom and an ‘aspect’ (severity, onset, duration, frequency and persistence); see Paap et al for a detailed analysis of this instrument). Reference Paap, Kreukels, Cohen-Kettenis, Richter-Appelt, De and Haraldsen18

Gender dysphoria

The Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale (UGDS) was used to measure the degree of experienced gender dysphoria. Reference Cohen-Kettenis and Van Goozen20

Axis I disorders

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview - Plus version 5.0.0 (MINI-Plus) was used to measure Axis I diagnoses. Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller21 This is a short, structured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV psychiatric disorders, allowing clinicians to assess Axis I diagnoses at the time of the interview (‘current diagnosis’) and disorders that have a longer history (‘current and lifetime diagnosis’).

Axis II disorders

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) was used to assess Axis II diagnoses; this is a semi-structured clinical interview. Reference First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams and Benjamin22 For logistic reasons the SCID-II was not administered in The Netherlands. As a consequence, results regarding Axis II disorders are based on data from Ghent, Hamburg and Oslo only.

Terminology

In this paper we use the term ‘gender identity disorder’ only when we refer to the clinical diagnosis.

Onset

Disorders were labelled as ‘early-onset’ when they met both criteria A and B for a diagnosis of gender identity disorder in childhood (see the online supplement); if they fulfilled neither criterion, they were categorised as ‘late-onset’ gender identity disorder. A residual group comprised cases fulfilling only one criterion (A or B). Reference Nieder, Herff, Cerwenka, Preuss, Cohen-Kettenis and De14

Statistical analysis

Chi-squared tests were used to test for differences in the occurrence of psychiatric problems among groups. The variables we tested included: gender (male to female v. female to male), country (Belgium, Germany, The Netherlands, Norway) and onset age (early v. late). Analyses were performed separately for Axis I and Axis II disorders. Axis I disorders were divided into six clusters: affective, anxiety, eating, substance-related, psychotic and other disorders. If marked differences were found for a certain group of disorders, a logistic regression analysis was performed with the psychiatric disorder as dependent variable and the group variables as independent variables to gain more insight in the relative contributions of each of the group variables in predicting whether or not the disorder was present. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 16.0.1 for Windows.

Results

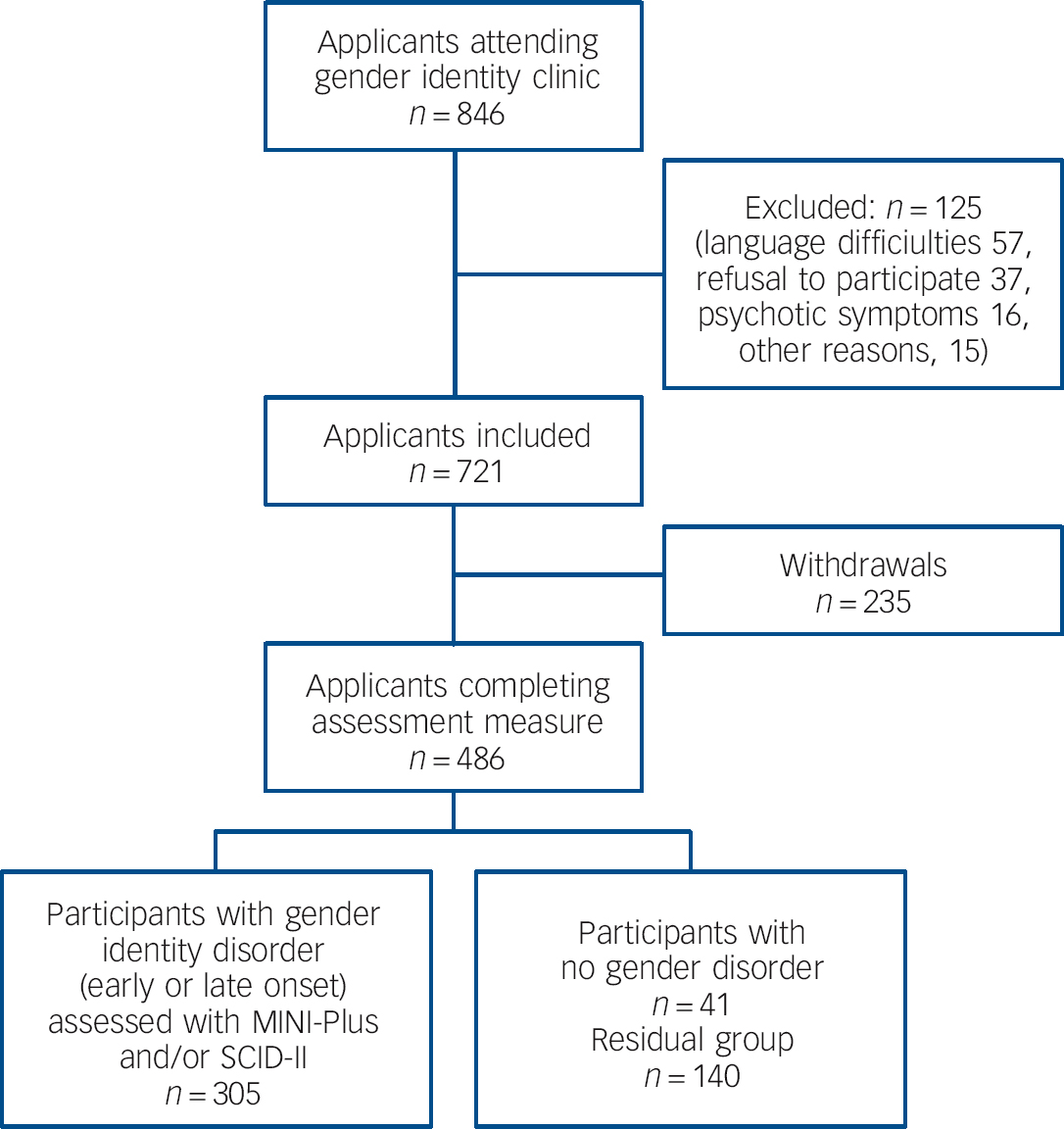

During the inclusion period 846 persons applied for treatment at the four gender clinics. Of these applicants, 125 were excluded from the study owing to an insufficient command of the language of the questionnaires (n = 57, 46%), refusal to participate (n = 37, 30%), clear psychotic symptoms at the time of application (n = 16, 13%) or for other reasons (n = 15, 11%). Consequently, 721 individuals completed at least one diagnostic instrument (Fig. 1). Some instruments were not completed owing to withdrawal (failing to attend consultations) or refusal to participate in the clinical interviews. Sample characteristics with regard to gender ratio, onset age and age at assessment are shown in Table 1. At the end of the inclusion period 305 individuals fulfilled criteria for early- or late-onset gender identity disorder and had been assessed by means of the MINI-Plus and/or the SCID-II. Forty-one applicants did not fulfil the gender identity disorder criteria and 140 were categorised into the residual gender identity disorder group. Of our final sample of 305 participants, 182 (59.7%) requested male to female and 123 (40.3%) female to male reassignment.

Axis I disorders

Almost 70% of the final sample of 305 participants showed one or more Axis I disorders current and lifetime (Table 2), mostly affective and anxiety disorders (respectively 60% and 28%). Prevalence rates were similar in both genders. No association was found between the presence of a current and lifetime Axis I diagnosis and age at assessment (P = 0.189). Patients with a current Axis I diagnosis were younger than those without one (P = 0.017). The degree of gender dysphoria was not associated with the presence of an Axis I diagnosis in general, neither was it associated with specific diagnoses such as depressive episode, panic attack, agoraphobia or substance-related problems. In the total cohort there was no difference in the prevalence of Axis I disorders between the early- and late-onset subgroups and this was true for both genders (P = 0.6 for the total cohort, P= 0.4 for the male to female group and P = 0.9 for the female to male group).

Fig. 1 Selection procedure and numbers of participants: early onset (fulfilled both DSM-IV criteria A and B in childhood); late onset (neither DSM-IV criterion); residual group (one criterion). MINI-Plus, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview - Plus; SCID-II, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Axis II Disorders.

Table 1 Sample characteristics with regard to gender ratio, onset age and age at assessment

| Belgium n = 63 |

Germany n = 57 |

The Netherlands n = 147 |

Norway n = 38 |

All countries n = 305 |

P Footnote a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender ratio (MtF:FtM) | 2.15:1 | 1.04:1 | 2.27:1 | 0.47:1 | 1.48:1 | <0.0001 |

| MtF, n | 43 | 29 | 102 | 8 | 182 | |

| FtM, n | 20 | 28 | 45 | 30 | 123 | |

| Age at onset, n (%) | ||||||

| Early onset | ||||||

| MtF | 25 (58) | 13 (45) | 50 (49) | 4 (50) | 92 (51) | |

| FtM | 20 (100) | 24 (86) | 37 (82) | 29 (97) | 110 (89) | |

| Late onset | ||||||

| MtF | 90 (49) | 0.01Footnote b | ||||

| FtM | 13 (11) | |||||

| Age at assessment, years: mean (s.d.) | ||||||

| MtF | 35.6 (9.9) | 34.6 (11.8) | 36.5 (13.2) | 21.6 (3.7) | 35.3 (12.3) | <0.0001Footnote c |

| FtM | 29.9 (9.0) | 29.2 (10.8) | 31.2 (11.3) | 22.8 (5.4) | 28.5 (10.1) |

FtM, female to male reassignment; MtF, male to female reassignment.

a. Differences between countries for the MtF plus FtM groups combined.

b. Early v. late onset.

c. Kruskal-Wallis test.

With regard to the prevalence of Axis I disorders among the four countries, we found a difference between countries among male to female transsexual subgroups, both for current and current and lifetime diagnoses (P = 0.001 for current diagnoses, P = 0.009 for current and lifetime diagnoses). Male to female transsexual patients in Germany and Norway showed higher prevalence rates compared with those in Belgium and The Netherlands. No difference was found between the female to male transsexual subgroups. Differences between countries were found for the affective cluster (P = 0.001 for both current and lifetime and current) and anxiety cluster (P = 0.029 for current and lifetime, P = 0.028 for current). In Germany, up to 80% of participants with the diagnosis of gender identity disorder showed affective symptoms currently or in the past compared with approximately 50% in the other countries. The Dutch patients had fewer anxiety symptoms currently or in the past compared with the other countries (20% rather than 30-40%).

Table 2 Axis I comorbidity in the four countries assessed with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview - Plus

| Belgium | Germany | The Netherlands | Norway | All countries | P Footnote a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n | ||||||

| MtF | 43 | 28 | 102 | 7 | 180 | |

| FtM | 20 | 25 | 45 | 28 | 118 | |

| One or more Axis I disorders, n (%) | ||||||

| Current | NS | |||||

| MtF | 13 (30) | 15 (54) | 34 (33) | 7 (100) | 69 (38) | |

| FtM | 8 (40) | 12 (48) | 16 (36) | 8 (29) | 44 (37) | |

| Current and lifetime | NS | |||||

| MtF | 25 (58) | 25 (89) | 66 (65) | 7 (100) | 123 (68) | |

| FtM | 19 (95) | 18 (72) | 30 (67) | 17 (61) | 84 (71) | |

| Affective disorders, n (%) | ||||||

| Current | 8 (13) | 21 (40) | 37 (25) | 15 (43) | 81 (27) | 0.005 |

| Current and lifetime | 29 (46) | 43 (81) | 88 (60) | 19 (54) | 179 (60) | <0.0001 |

| Anxiety disorders, n (%) | ||||||

| Current | 14 (22) | 13 (24) | 15 (10) | 8 (23) | 50 (17) | 0.035 |

| Current and lifetime | 24 (38) | 20 (38) | 31 (21) | 10 (29) | 85 (28) | 0.020 |

| Substance-related disorders, n (%) | ||||||

| Current | 4 (6) | 4 (8) | 14 (10) | 2 (6) | 24 (8) | NS |

| Current and lifetime | 16 (25) | 6 (11) | 23 (16) | 2 (6) | 47 (16) | 0.028 |

| Eating disorders, n (%) | ||||||

| Current | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | NS |

| Current and lifetime | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 1 (1) | 2 (6) | 6 (2) | NS |

| Psychotic disorders, n (%) | ||||||

| Current and lifetime | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 1 (3) | 4 (1) | NS |

FtM, female to male reassignment; MtF, male to female reassignment; NS, not significant.

a. Difference between countries for the MtF plus FtM groups combined.

In almost 30% of the participants suicide risk was identified (meaning they had suicidal ideations and/or plans during the preceding month and/or had ever attempted suicide). Female to male and male to female subgroups reported similar degrees of suicidal ideation (P = 0.671). There was no difference between the early- and late-onset groups (P = 0.165). Suicide risk was not associated with having an Axis II diagnosis (P = 0.536). No difference was found between the four countries.

A logistic regression was performed with ‘affective disorder’ as a dependent variable to gain a better understanding of the factors that might be associated with the differences between the countries. We chose to retain only significant effects in the final model. A forward step-wise strategy was used, adding the following variables one at a time: assessment age (⩽30 years v. >30 years), onset age, gender and country. Interaction effects between variables were also calculated and added to the model. Our final model contained the variables country, gender and country×gender. The main effects of country and gender were no longer significant when the interaction effect was added. The interaction effect indicated that people undergoing male to female reassignment were more likely to have an affective disorder in Germany (odds ratio (OR) = 11.4, P = 0.013) and Norway (OR = 20.0, P = 0.014); Belgium was used as the reference category. No difference between the countries was found for the female to male subgroups.

Axis II disorders

Schizoid, avoidant and borderline personality disorders were most prevalent, in 5%, 4% and 7% of our sample respectively. The overall prevalence rate for personality disorders was 15% (Table 3). No difference was found between the male to female transsexual group (12% had one or more personality disorders) and the female to male group (one or more personality disorders in 18%). The Axis II prevalence rates were similar in the three countries. In the total cohort and in the male to female subgroup there was no difference in prevalence of Axis II disorders between the early- and late-onset groups. In the female to male group, individuals with late-onset disorder had significantly more personality disorders (P = 0.003). Individuals showing borderline personality disorder were younger at the time of application to the clinic (P = 0.009); this group also showed a trend towards stronger gender dysphoria (P = 0.073). Personality disorders were also clustered in three groups. Cluster C disorders were most common (63% of all personality disorders), followed by cluster B (45%) and cluster A (41%). No difference was found between the four countries with regard to clusters of personality disorders.

Discussion

Overall, we found that Axis I disorders were more common in applicants for treatment of gender identity disorder compared with the general populations of the participating countries. Reference Bruffaerts, Bonnewyn, Van Oyen, Demarest and Demyttenaere23-Reference Kringlen, Torgersen and Cramer26 On closer inspection we found that this difference was mainly due to affective and anxiety disorders, with the gender identity disorder group showing higher rates than the general population. This was the case in all four countries and for both male to female and female to male reassignment groups. Other Axis I clusters were found to be equally prevalent compared with the general population. Although the prevalence rates of affective and anxiety disorders in the general population differed slightly between the four countries, this cannot fully account for the differences we found in our population. A new study would be needed to assess which factors (e.g. patient and clinician characteristics or social differences among the countries) might explain these findings.

Table 3 Axis II disorders assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders

| Belgium n = 60 |

Germany n = 55 |

Norway n = 29 |

All countries n = 144 |

P Footnote a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One or more Axis II disorders, n (%) | 10 (17) | 10 (18) | 2 (7) | 22 (15) | NS |

| Cluster A | 4 (7) | 3 (6) | 2 (7) | 9 (6) | NS |

| Cluster B | 5 (8) | 3 (6) | 2 (7) | 10 (7) | NS |

| Cluster C | 8 (13) | 6 (11) | 0 (0) | 14 (10) | NS |

NS, not significant.

a. Difference between countries.

The incongruence between gender identity and social life and/or bodily characteristics experienced by individuals diagnosed with gender identity disorder can cause much distress that may lead to affective and anxiety problems and even disorders. Follow-up studies often show a resolution of depressive and anxious symptoms throughout the treatment process. Reference Mate-Kole, Freschi and Robin27-Reference Gomez-Gil, Vidal-Hagemeijer and Salamero29 Furthermore, the phenomenon of ‘minority stress’ can also explain the high prevalence of affective disorders. Social discrimination and stigmatisation may cause a diminished quality of life, particularly with regard to mental health. Reference Newfield, Hart, Dibble and Kohler30

The findings with regard to the prevalence of suicide risk confirm results on this topic. Reference Hoshiai, Matsumoto, Sato, Ohnishi, Okabe and Kishimoto8,Reference Terada, Matsumoto, Sato, Okabe, Kishimoto and Uchitomi31,Reference Haas, Eliason, Mays, Mathy, Cochran and D'Augelli32 Terada et al reported that the high prevalence of suicidality in their gender identity disorder population was not related to psychiatric comorbidity. Reference Haas, Eliason, Mays, Mathy, Cochran and D'Augelli32 This suggests that gender identity disorder is an independent risk factor for suicidal behaviour and this could be interpreted as an (inappropriate) coping strategy. Reference Terada, Matsumoto, Sato, Okabe, Kishimoto and Uchitomi31 In a report on suicide and suicide risk in transgender populations, Haas et al emphasised high suicide and suicide attempt rates. Reference Haas, Eliason, Mays, Mathy, Cochran and D'Augelli32 Besides the high prevalence of depression, anxiety and substance misuse in these populations, factors such as parental rejection and discrimination are linked to elevated risk of suicidal behaviour. A longitudinal study in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth by Liu & Mustanski showed that childhood gender non-conformity and victimisation were associated with increased risk of self-harm and suicidal ideation. Reference Liu and Mustanski33 In our study, suicidality was assessed using the MINI-Plus interview, which was also used to measure Axis I disorders; we therefore could not investigate whether there was an association between suicide risk and having an Axis I disorder. No association was found between suicide risk and the presence of personality disorder, which again illustrates that gender identity disorder may be an independent risk factor for suicidality.

Major psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder or psychosis were rarely found and did not exceed prevalence in the general population. Reference Bruffaerts, Bonnewyn, Van Oyen, Demarest and Demyttenaere23-Reference De Graaf, Ten Have, van and van25 Since the presence of psychosis was explicitly defined as an exclusion criterion, there was a severe bias. However, the low number of applicants (16 of 846) excluded for this reason does not suggest that our findings were a severe underestimation of the true prevalence.

Comparison between the prevalence of Axis I disorders in our study and rates in the general population should be interpreted with caution: epidemiological studies in different countries use different instruments and sometimes data on certain clinical categories are simply missing. Still, it is clear that the prevalence of both current and current and lifetime Axis I disorders in our study population is higher than in the general population of all four countries. This difference is mainly due to the high prevalence (up to three times higher compared with the general population) of affective and anxiety disorders. For example, current affective problems occur at rates between 6% (Belgium and The Netherlands) and 11-12% (Germany and Norway) in the general population, whereas in our sample prevalence rates ranged from 13% and 25% (Belgium and The Netherlands) to 40% and 35% (Germany and Norway). Reference Bruffaerts, Bonnewyn, Van Oyen, Demarest and Demyttenaere23-Reference Kringlen, Torgersen and Cramer26 The European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project, conducted in six European countries (including Belgium, Germany and The Netherlands), found a lifetime prevalence of any mental disorder in 25% of respondents, a much lower percentage than in our cohort (see above). Any mood disorder and any anxiety disorder were found in 14%. Women were twice as likely to have any mental problem compared with men, especially with regard to mood and anxiety disorders which occurred two to three times more frequently in women. Reference Alonso, Angermeyer, Bernert, Bruffaerts, Brugha and Bryson34 In our sample Axis I disorders were equally distributed in the male to female and female to male reassignment subgroups, except in Norway where they were more common in the female to male group.

The low degree of psychopathology with regard to personality disorders replicates the findings of some earlier studies, Reference Miach, Berah, Butcher and Rouse35 but contradicts the high prevalence of such disorders found in similar studies by Hepp et al and Madeddu et al: both studies also used the SCID-II interview and included only people with gender identity disorder, Reference Hepp, Kraemer, Schnyder, Miller and Delsignore4,Reference Madeddu, Prunas and Hartmann36 as we did in our study. A potential explanation for our findings contradicting those of Hepp et al and Madeddu et al could be that some individuals with a personality disorder were more reluctant to participate in our study owing to a lack of confidence in professional caregivers. Our findings accord with prevalence rates of personality disorders in the general population of Germany (10.0%) and Norway (13.4%). Reference Maier, Lichtermann, Klinger, Heun and Hallmayer37,Reference Torgersen, Kringlen and Cramer38 No information on prevalence exists for Belgium; however, in The Netherlands the prevalence is 13.5%.39 Moreover, the distribution in clusters of personality disorders found in this study resembles the distribution found in epidemiological studies in Germany, Norway and The Netherlands. Reference Maier, Lichtermann, Klinger, Heun and Hallmayer37-39 Statistics on the Axis II data should be interpreted with caution, owing to the low numbers in most disorder categories.

In contrast to some reports (and the general impression among clinicians) that individuals with late-onset gender identity disorder are more psychiatrically affected, Reference Smith, van, Kuiper and Cohen-Kettenis15 no difference concerning psychiatric comorbidity, whether Axis I and Axis II, was found between individuals with early- v. late-onset disorder. The only exception was among the female to male reassignment group, in which those with late-onset disorder showed more Axis II problems than those with early-onset disorder, but numbers were very small (only four individuals in the late-onset group) and this finding needs to be replicated in a larger study.

In conclusion, our findings show that individuals with gender identity disorder have more psychiatric problems than the general population: mostly these are affective and anxiety problems. Although more decisive conclusions cannot be drawn owing to the cross-sectional design of our study, psychopathological symptoms seem to be closely related to the individual’s longstanding and strongly felt identification with the other gender. Further research should focus on long-term follow-up studies using standardised diagnostic and therapeutic protocols in order to determine whether the Axis I diagnosis rate decreases with treatment and whether such a decrease manifests in any particular subcategory of patient. This might lead to a better understanding of the nature of gender identity disorder and of the psychiatric symptoms experienced in connection with this disorder.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all clinicians who participated in this study, collected the data and were responsible for the data entry

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.