Perinatal mental health is a leading public health issue because of its negative effect on both maternal and child outcomes and its significant economic cost to society if left untreated. Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman and McCallum1,Reference Howard, Molyneaux, Dennis, Rochat, Stein and Milgrom2 A common mental health problem women experience during the perinatal (pregnancy and postpartum) period is anxiety Reference Garthus-Niegel, von Soest, Knoph, Simonsen, Torgersen and Eberhard-Gran3 and despite it being a frequent comorbidity with depression, Reference Falah-Hassani, Shiri and Dennis4 it has received limited attention from researchers and health professionals. This is an important clinical omission given the ever-growing evidence indicating maternal anxiety both antenatally and postnatally may lead to serious negative outcomes. Maternal antenatal anxiety has been associated with increased childbirth fear, Reference Hall, Hauck, Carty, Hutton, Fenwick and Stoll5 a preference for Caesarean section delivery, Reference Rubertsson, Hellstrom, Cross and Sydsjo6 decreased effective coping strategies, Reference George, Luz, De Tychey, Thilly and Spitz7 higher rates of eating disorders Reference Micali, Simonoff and Treasure8 and an increased risk for suicide. Reference Farias, Pinto, Teofilo, Vilela, Vaz and Nardi9 It also has important neonatal implications as it has been linked to increased preterm birth rates, Reference Ibanez, Charles, Forhan, Magnin, Thiebaugeorges and Kaminski10,Reference Sanchez, Puente, Atencio, Qiu, Yanez and Gelaye11 lower Apgar scores Reference Berle, Mykletun, Daltveit, Rasmussen, Holsten and Dahl12 and decreased birth length. Reference Broekman, Chan, Chong, Kwek, Cohen and Haley13 Further, antenatal anxiety is a risk factor for poor child developmental trajectories. Reference Glover14 In a study conducted in the Netherlands, antenatal anxiety early in pregnancy significantly increased the risk for cognitive disorders in children at 14 and 15 years of age. Reference Van den Bergh, Mennes, Oosterlaan, Stevens, Stiers and Marcoen15 In the same population, hierarchical multiple regression analyses showed that maternal anxiety at 12–22 weeks' gestation explained 22%, 15% and 9% of the variance in cross-situational attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms, externalising problems and self-reported anxiety, respectively, among Dutch children aged 8 and 9 years. Reference Van den Bergh and Marcoen16 The link between antenatal anxiety and behavioural/emotional problems in children at 4 years of age after adjusting for covariates has also been reported in a UK study. Reference O'Connor, Heron and Glover17 More recently, maternal antenatal anxiety was associated with an increased risk of child attention problems after accounting for confounders. Reference Van Batenburg-Eddes, Brion, Henrichs, Jaddoe, Hofman and Verhulst18 Similar adverse effects have been found for maternal postnatal anxiety, which has been associated with negative and disengaged parenting Reference McLeod, Wood and Weisz19–Reference Bögels and Brechman-Toussaint21 and overcontrolling maternal behaviours that increase the likelihood of internalising and externalising difficulties in the child. Reference Barker, Jaffee, Uher and Maughan20,Reference Williams, Kertz, Schrock and Woodruff-Borden22,Reference Joussemet, Vitaro, Barker, Cote, Nagin and Zoccolillo23 The emergent evidence highlights the need for early identification of maternal anxiety across the perinatal period and the provision of effective treatment. However, reliable estimates of maternal anxiety to guide clinical interventions are unknown because of widely varying published prevalence rates. The aim of this systematic review was to establish summary estimates for the prevalence of maternal anxiety in the antenatal and postnatal periods.

Method

Search strategy and study eligibility

The protocol and reporting of the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis were based on PRISMA guidelines. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group24 Comprehensive literature searches were conducted in MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Web of Science, Scopus, ResearchGate and Google Scholar from 1950 until 13 January 2016 using predefined key terms (online Table DS1) such as (postpartum OR puerperium OR pregnancy OR gestation OR postbirth OR post-birth OR antenatal OR prenatal OR postnatal) AND (mood disorders OR depressive disorder OR depression OR depressive symptoms OR anxiety disorders OR anxiety). We used MeSH terms and key words in MEDLINE and Emtree terms and key words in Embase. The titles and abstracts of all identified citations were screened for relevance and the full text of potentially relevant articles were obtained and assessed for eligibility. In addition, the reference lists of relevant articles were hand searched.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: (a) included women who were 16 years or older; (b) assessed for antenatal or postnatal anxiety using a validated diagnostic or self-report instrument; (c) reported the results of peer-reviewed research based on cross-sectional or cohort studies; and (d) provided data in order to estimate the prevalence of anxiety. Studies were excluded if they: (a) were conducted among self-selected volunteers; (b) recruited high-risk women; (c) reported results for only a subsample of a study population; (d) reported duplicate data from a single database; (e) reported only mean data; (e) reported combined prevalence for depression and anxiety; or (f) did not report a cut-off point for anxiety. We contacted over 70 authors for additional information, particularly those who reported only mean data, no cut-off data or had missing information, with approximately a third providing us with additional results. For studies with duplicate data from a single database, we selected the study with the larger sample size.

Data extraction and quality assessment

We extracted individual details of the included studies such as year of publication, study population, recruitment method, sample size used in the analysis, measure of anxiety, cut-off points, timing of assessments and prevalence of anxiety variously defined. The risk of bias in the included studies was independently rated by two reviewers (K.F.-H. and R.S.) using criteria adapted from the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool for observational studies. Reference Armijo-Olivo, Stiles, Hagen, Biondo and Cummings25 Three domains were assessed: selection bias, detection bias and attrition bias. Selection bias was classified as: (a) low: likely to be representative of the target population or subgroup of the target population (i.e. specific age group or geographic area) and response rate was 80% or higher; (b) moderate: likely to be somewhat representative of the target population or a restricted subgroup of the target population and response rate was 60–79%; or (c) high: target population was self-referred/volunteers, or response rate was less than 60%. Detection bias was classified as follows: (a) low: the outcome was defined by clinical diagnosis; (b) moderate: the outcome was assessed by a validated questionnaire; or (c) high: the outcome was self-reported. Finally, attrition bias was classified as follows: (a) low: follow-up participation rate was more than 80% or missing data was less than 20%; (b) moderate: follow-up participation rate was 60–79% or missing data was 20–40%; or (c) high: follow-up participation rate was less than 60% or missing data was more than 40%. Any disagreements in quality ratings were resolved by discussion (K.F.-H., R.S.), and if necessary with the involvement of another author (C.-L.D.).

Data synthesis and analysis

Many studies reported an estimate for the prevalence of antenatal or postnatal anxiety for more than one time point for the same participants. In order to include each study with multiple time-points only once in a specific meta-analysis, an overall prevalence of antenatal or postnatal anxiety was estimated using an average sample size and an average number of events (for example estimate for the 1–24 weeks' postnatal anxiety symptoms). The prospective cohort studies included in the current meta-analysis determined the prevalence of anxiety rather than the incidence of anxiety. We therefore combined both cross-sectional and cohort studies in a single analysis. Anxiety was assessed using diverse measures, cut-off scores and perinatal time periods. We performed meta-analyses based on the following anxiety categories: (a) self-reported state anxiety symptoms, (b) self-reported trait anxiety, (c) clinical diagnosis of any anxiety disorder, and (d) clinical diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder. We further performed analyses according to pregnancy trimester and postpartum time period. We used a random-effects meta-analysis to combine the estimates of different studies. Reference Higgins and Green26 The presence of heterogeneity across the studies was assessed using the I 2-statistic. Reference Higgins and Thompson27 An I 2-statistic less than 25% indicates small inconsistency and more than 50% indicates large inconsistency. Reference Higgins and Thompson27 We used meta-regression to assess the differences between subgroups. Reference Higgins and Green26 We performed subgroup analyses according to year of publication (⩾2009 v. ⩽2010), income of study country based on World Bank categories (low to middle income v. high income), selection bias and attrition bias. Stata (version 13) was used for the meta-analyses.

Results

Study characteristics

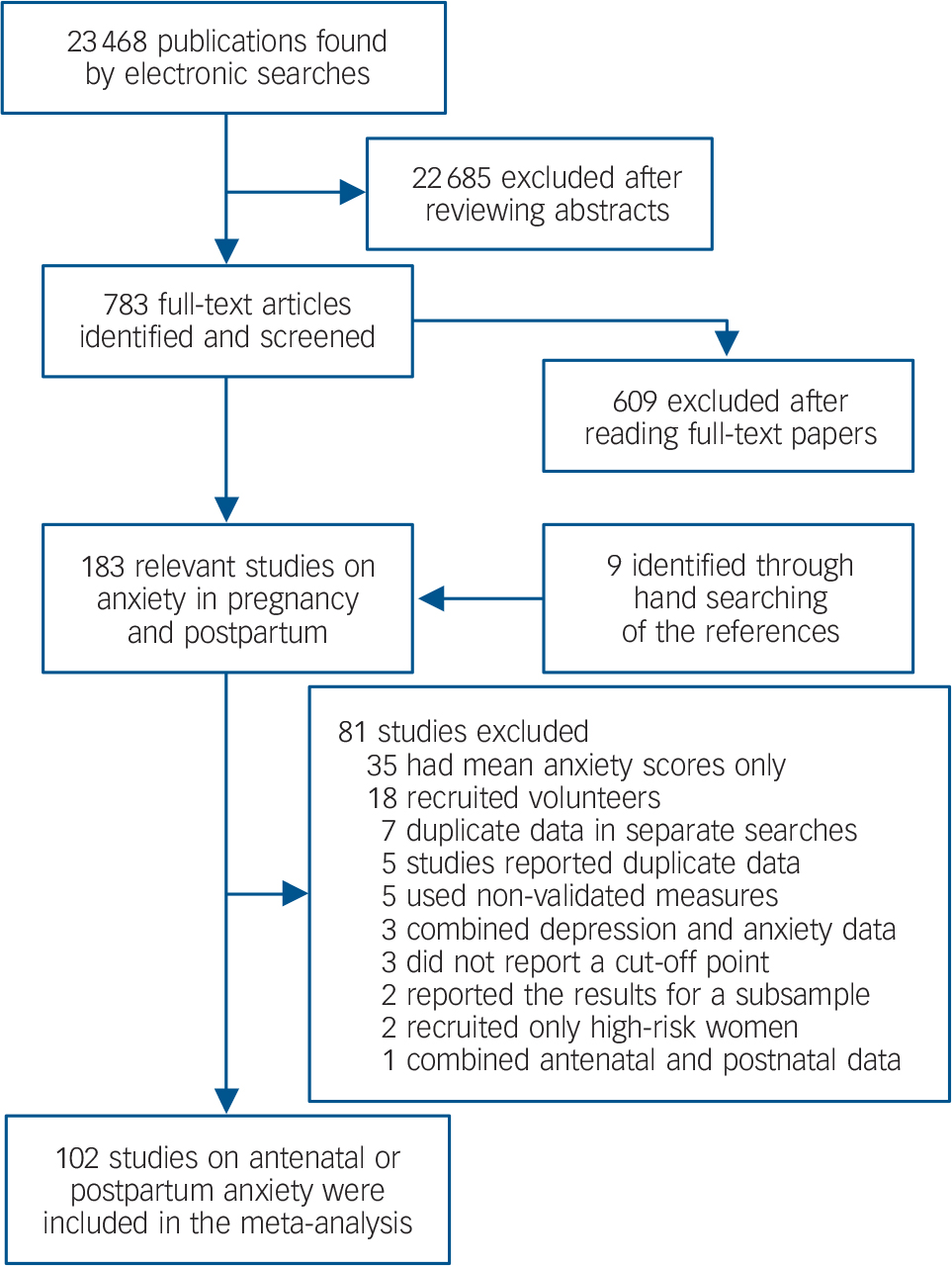

The study selection process is presented in Fig. 1. The literature search yielded 23 468 unique references, of which 22 685 were excluded following title and abstract screening. Overall, 783 full papers were retrieved and assessed. Of these, 183 papers were relevant following full-text screening: 174 were identified from searches of electronic databases and 9 from hand searches of references. From these 183 studies, a further 81 were excluded primarily for only having mean anxiety scores (n = 35) and volunteer samples (n = 18). In total, 102 studies on antenatal or postnatal anxiety were included in the meta-analyses with assistance from 26 authors who were contacted and provided additional information to allow their studies to be incorporated (see Acknowledgements).

Fig. 1 Flow diagram for identifying studies on the prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety.

Characteristics of the included studies are provided in online Table DS2. In total, 70 studies provided data on the prevalence of antenatal anxiety and 57 studies provided data related to postnatal anxiety. The studies were conducted in 34 different countries spanning six continents and included 221 974 women. The countries with the largest number of included studies comprised the USA (n = 19), Australia (n = 11), Brazil (n = 9), Canada (n = 8), France (n = 4), Netherlands (n = 4), Norway (n = 4), UK (n = 4), Germany (n = 3) and Sweden (n = 3). Ten countries from the Asian continent provided data (Bangladesh, China, Hong Kong, Israel, Japan, Jordan, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore and Vietnam) as did four countries from Africa (Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa and Tanzania). In total, there were 24 countries classified as low to middle income using World Bank categories. The majority of studies used the self-report State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) to measure state anxiety symptoms (n = 51) or trait anxiety (n = 24). The most common diagnostic interviews to assess for any anxiety disorders or generalised anxiety disorder were the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (n = 6), Composite International Diagnostic Interview (n = 5) and Structural Clinical Interview for DSM (n = 5). When evaluated by the modified Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool, eight studies were rated as having low risk of selection bias, 69 as having moderate risk and 25 studies as having high risk (Table 2). In total, 17 studies were rated as having low risk of detection bias, 85 as having moderate risk, and none as having high risk. For attrition bias, 77 studies were rated as low risk, 17 as moderate risk and 8 as high risk.

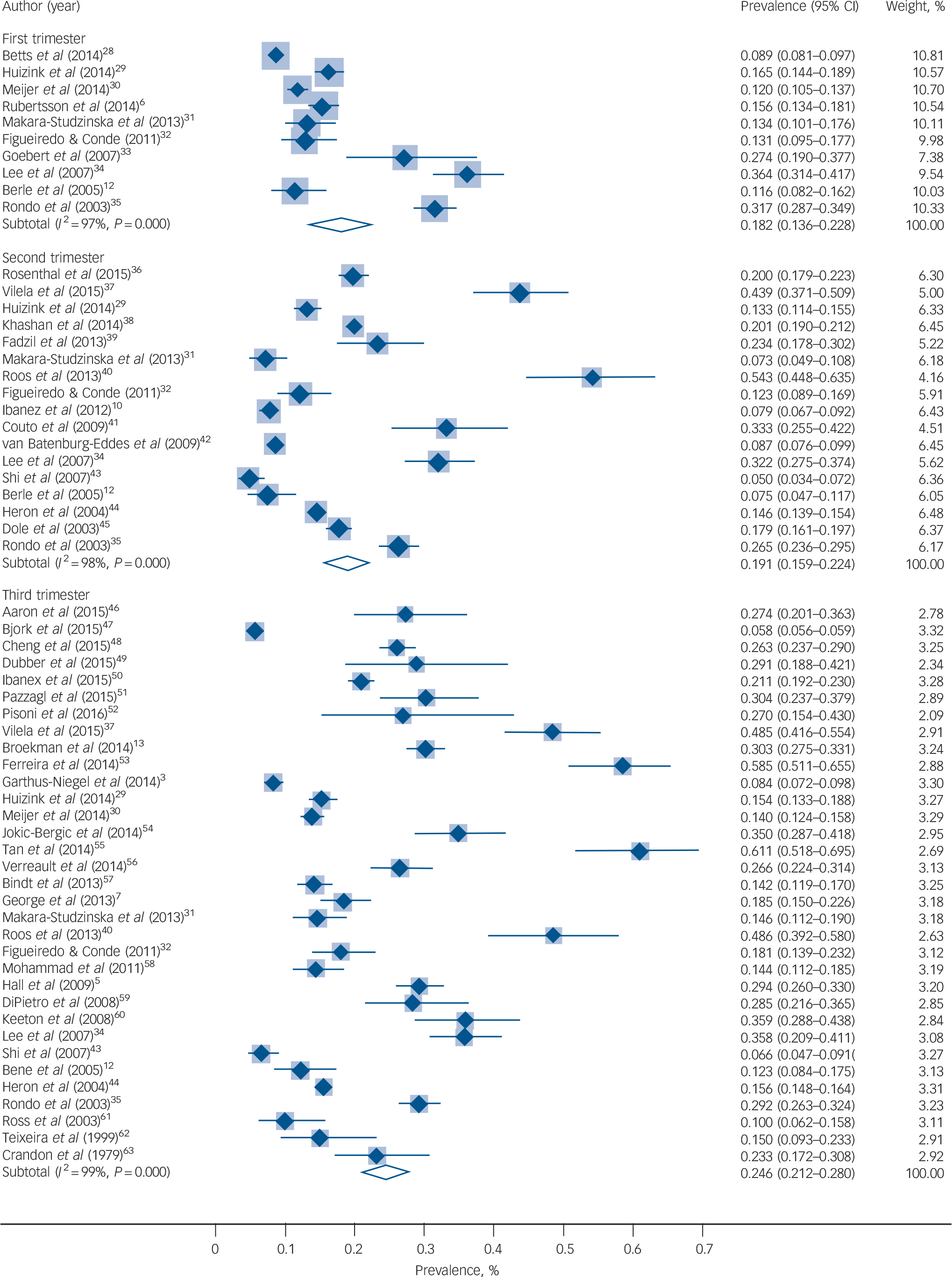

Prevalence of antenatal anxiety

Meta-analytic pooling of the estimates yielded the prevalence of self-reported anxiety symptoms to be 18.2% (95% CI 13.6–22.8, 10 studies, n = 10 577) Reference Rubertsson, Hellstrom, Cross and Sydsjo6,Reference Berle, Mykletun, Daltveit, Rasmussen, Holsten and Dahl12,Reference Betts, Williams, Najman and Alati28–Reference Rondo, Ferreira, Nogueira, Ribeiro, Lobert and Artes35 for the first trimester, 19.1% (95% CI 15.9–22.4, 17 studies, n = 24 499) Reference Ibanez, Charles, Forhan, Magnin, Thiebaugeorges and Kaminski10,Reference Berle, Mykletun, Daltveit, Rasmussen, Holsten and Dahl12,Reference Huizink, Menting, Oosterman, Verhage, Kunseler and Schuengel29,Reference Makara-Studzinska, Morylowska-Topolska, Sygit, Sygit and Gozdziewska31,Reference Figueiredo and Conde32,Reference Lee, Lam, Sze Mun Lau, Chong, Chui and Fong34–Reference Dole, Savitz, Hertz-Picciotto, Siega-Riz, McMahon and Buekens45 for the second trimester and 24.6% (95% CI 21.2–28.0, 33 studies, n = 116 720) Reference Garthus-Niegel, von Soest, Knoph, Simonsen, Torgersen and Eberhard-Gran3,Reference Hall, Hauck, Carty, Hutton, Fenwick and Stoll5,Reference George, Luz, De Tychey, Thilly and Spitz7,Reference Berle, Mykletun, Daltveit, Rasmussen, Holsten and Dahl12,Reference Broekman, Chan, Chong, Kwek, Cohen and Haley13,Reference Huizink, Menting, Oosterman, Verhage, Kunseler and Schuengel29–Reference Figueiredo and Conde32,Reference Lee, Lam, Sze Mun Lau, Chong, Chui and Fong34,Reference Rondo, Ferreira, Nogueira, Ribeiro, Lobert and Artes35,Reference Vilela, Pinto, Rebelo, Benaim, Lepsch and Dias-Silva37,Reference Roos, Faure, Lochner, Vythilingum and Stein40,Reference Shi, Tang, Cheng, Su, Qi and Yang43,Reference Heron, O'Connor, Evans, Golding, Glover and Team44,Reference Aaron, Bonacquisti, Geller and Polansky46–Reference Crandon63 for the third trimester (Table 1 and Fig. 2). The overall pooled prevalence for self-reported anxiety symptoms across the three trimesters was 22.9% (95% CI 20.5–25.2, 52 studies, n = 142 833). The prevalence for self-reported trait anxiety was 29.1% (95% CI 11.7–46.4, 4 studies, n = 2388) for the first trimester, and 32.5% (95% CI 27.6–37.4, 12 studies, n = 5568) for the third trimester. The prevalence for a clinical diagnosis of any anxiety disorder was 18.0% (95% CI 15.0–21.1, 2 studies, n = 615) for the first trimester, 15.2% (95% CI 3.6–26.7, 4 studies, n = 3002) for the second trimester and 15.4% (95% CI 5.1–25.6, 4 studies, n = 1603) for the third trimester. The prevalence of a clinical diagnosis of a generalised anxiety disorder was 5.3% (95% CI 1.5–9.1, 3 studies, n = 3338) for the first trimester, 0.3% (95 CI % 0.1–0.6, 2 studies, n = 1862) and 4.1% (95% CI 1.0–7.2, 4 studies, n = 1455) for the second and third trimester, respectively. Overall, the prevalence of any anxiety disorder across the three trimesters was 15.2% (95% CI 9.0–21.4, 9 studies, n = 4648, Table 1 and online Fig. DS1) and that of a generalised anxiety disorder was 4.1% (95% CI 1.9–6.2, 10 studies, n = 6910, Table 1 and online Fig. DS2).

Fig. 2 Prevalence of antenatal anxiety symptoms.

Table 1 Prevalence of antenatal anxiety

| All studies | Studies without high risk of selection/attrition bias | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time period, measure and outcome |

Studies, n |

Sample | Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

I 2, % | Studies, n |

Sample | Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

I 2, % |

| First trimester | ||||||||

| Self-report | ||||||||

| Trait anxiety | 4 | 2 388 | 29.1 (11.7–46.4) | 99.0 | 2 | 1 532 | 38.4 (36.1–40.7) | 99.6 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 10 | 10 577 | 18.2 (13.6–22.8) | 97.3 | 9 | 8 974 | 19.1 (13.3–24.8) | 97.6 |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||||||||

| Any anxiety disorder | 2 | 615 | 18.0 (15.0–21.1) | 99.7 | 2 | 615 | 18.0 (15.0–21.1) | 99.7 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 3 | 3 338 | 5.3 (1.5–9.1) | 94.7 | 3 | 3 338 | 5.3 (1.5–9.1) | 94.7 |

| Second trimester | ||||||||

| Self-report | ||||||||

| Trait anxiety | 1 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – |

| Anxiety symptoms | 17 | 24 499 | 19.1 (15.9–22.4) | 97.9 | 13 | 18 430 | 19.4 (15.7–23.2) | 97.3 |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||||||||

| Any anxiety disorder | 4 | 3 002 | 15.2 (3.6–26.7) | 98.7 | 4 | 3 002 | 15.2 (3.6–26.7) | 98.7 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 2 | 1 862 | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 97.3 | 2 | 1 862 | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 97.3 |

| Third trimester | ||||||||

| Self-report | ||||||||

| Trait anxiety | 12 | 5 568 | 32.5 (27.6–37.4) | 92.5 | 8 | 4 168 | 31.4 (25.9–36.9) | 92.4 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 33 | 116 720 | 24.6 (21.2–28.0) | 98.9 | 22 | 16 120 | 23.4 (19.9–26.9) | 95.9 |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||||||||

| Any anxiety disorder | 4 | 1 603 | 15.4 (5.1–25.6) | 97.6 | 2 | 615 | 14.2 (11.5–16.9) | 99.6 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 4 | 1 455 | 4.1 (1.0–7.2) | 92.5 | 3 | 958 | 2.3 (0.2–4.4) | 80.1 |

| First, second or third trimester | ||||||||

| Self-report | ||||||||

| Trait anxiety | 18 | 8 086 | 31.5 (26.3–36.7) | 96.3 | 11 | 5 372 | 34.3 (28.5–40.1) | 94.9 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 52 | 142 833 | 22.9 (20.5–25.2) | 99.0 | 35 | 35 656 | 22.4 (19.6–25.1) | 97.8 |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||||||||

| Any anxiety disorder | 9 | 4 648 | 15.2 (9.0–21.4) | 97.7 | 6 | 3 560 | 14.8 (6.4–23.3) | 98.0 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 10 | 6 910 | 4.1 (1.9–6.2) | 97.3 | 9 | 6 413 | 3.6 (1.4–5.7) | 97.3 |

Prevalence of postnatal anxiety

The prevalence of self-reported anxiety symptoms was 17.8% (95% CI 14.2–21.4, 14 studies, n = 10 928) at 1–4 weeks postpartum, 14.9% (95% CI 12.3–17.5, 22 studies, n = 19 158) at 5–12 weeks postpartum, 15.0% (95% CI 13.7–16.4, 39 studies, n = 145 293) at 1–24 weeks postpartum, and 14.8% (95% CI 10.9–18.8, 7 studies, n = 11 528) at >24 weeks postpartum (Table 2 and online Fig. DS3). The prevalence of having a clinical diagnosis of any anxiety disorder was 9.6% (95% CI 3.4–15.9, 5 studies, n = 2712) at 5–12 weeks postpartum, 9.9% (95% CI 6.1–13.8, 9 studies, n = 28 495) at 1–24 weeks postpartum and 9.3% (95% CI 5.5–13.1, 5 studies, n = 28 244) at >24 weeks postpartum (Table 2 and online Fig. DS1). The prevalence of a generalised anxiety disorder was 6.7% (95% CI 0.6–12.7, 4 studies, n = 1979) at 5–12 weeks postpartum, 5.7% (95% CI 2.3–9.2, 6 studies, n = 2667) at 1–24 weeks postpartum, and 4.2% (95% CI 1.5–6.9, 4 studies, n = 1950) at >24 weeks postpartum (Table 2 and online Fig. DS2).

Table 2 Prevalence of postnatal anxiety

| All studies | Studies without high risk of selection/attrition bias | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time period, measure and outcome |

Studies, n |

Sample | Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

I 2, % | Studies, n |

Sample | Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

I 2, % |

| 1–4 weeks postpartum | ||||||||

| Self-report | ||||||||

| Trait anxiety | 6 | 2 724 | 23.1 (14.5–31.7) | 97.1 | 6 | 2 724 | 23.1 (14.5–31.7) | 97.1 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 14 | 10 928 | 17.8 (14.2–21.4) | 96.1 | 12 | 10 065 | 17.8 (13.9–21.6) | 96.2 |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||||||||

| Any anxiety disorder | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5–12 weeks postpartum | ||||||||

| Self-report | ||||||||

| Trait anxiety | 5 | 1 260 | 23.4 (13.8–33.0) | 92.8 | 4 | 1 140 | 23.1 (11.4–34.8) | 94.6 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 22 | 19 158 | 14.9 (12.3–17.5) | 97.1 | 16 | 14 024 | 15.2 (11.5–18.9) | 97.5 |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||||||||

| Any anxiety disorder | 5 | 2 712 | 9.6 (3.4–15.9) | 97.6 | 4 | 2 413 | 11.3 (2.6–19.9) | 98.1 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 4 | 1 979 | 6.7 (0.6–12.7) | 97.8 | 4 | 1 979 | 6.7 (0.6–12.7) | 97.8 |

| 1–24 weeks postpartum | ||||||||

| Self-report | ||||||||

| Trait anxiety | 10 | 3 533 | 23.2 (16.0–30.4) | 96.6 | 8 | 3 313 | 22.8 (14.6–31.0) | 97.3 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 39 | 145 293 | 15.0 (13.7–16.4) | 98.5 | 26 | 45 104 | 17.2 (14.3–20.0) | 98.8 |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||||||||

| Any anxiety disorder | 9 | 28 495 | 9.9 (6.1–13.8) | 97.8 | 7 | 28 096 | 9.9 (5.4–14.4) | 98.2 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 6 | 2 667 | 5.7 (2.3–9.2) | 94.5 | 6 | 2 667 | 5.7 (2.3–9.2) | 94.5 |

| >24 weeks postpartum | ||||||||

| Self-report | ||||||||

| Trait anxiety | 1 | |||||||

| Anxiety symptoms | 7 | 11 528 | 14.8 (10.9–18.8) | 95.9 | 5 | 9 714 | 11.5 (8.2–14.8) | 89.2 |

| Clinical diagnosis | ||||||||

| Any anxiety disorder | 5 | 28 244 | 9.3 (5.5–13.1) | 98.0 | 5 | 28 244 | 9.3 (5.5–13.1) | 98.0 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 4 | 1 950 | 4.2 (1.5–6.9) | 89.3 | 4 | 1 950 | 4.2 (1.5–6.9) | 89.3 |

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

Excluding studies with high risk of selection or attrition bias did not change markedly the estimates for the prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety symptoms, any anxiety disorder or a generalised anxiety disorder (Tables 1 and 2). The prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety symptoms as well as that of antenatal and postnatal anxiety disorder did not differ with regard to year of publication (>2010 v. <2009), selection bias and attrition bias (Table 3). However, the prevalence of antenatal anxiety symptoms across all trimesters was significantly higher in low- to middle-income countries (34.4%, 95% CI 25.0–43.8, 13 studies, n= 5089) in comparison with high-income countries (19.4% 95% CI 17.0–21.8, 39 studies, n= 137 744). The prevalence of postnatal anxiety symptoms across the first 6 months postpartum was also significantly higher in low- to middle-income countries (25.9%, 95% CI 13.7–38.1, 5 studies, n= 2159) in comparison with high-income countries (13.7%, 95% CI 12.3–15.0, 34 studies, n= 143 134) (Table 3). Studies with moderate or high risk of selection bias may have overestimated the prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety symptoms.

Table 3 Prevalence of anxiety symptoms and any anxiety disorder according to year of publication, country income and methodological quality

| Anxiety symptoms | Any anxiety disorder | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies, n |

Sample | Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

P | Studies, n |

Sample | Prevalence, % (95% CI) |

P | |

|

Antenatal (first, second

or third trimesters) |

||||||||

| Publication year | 0.99 | 0.15 | ||||||

| ⩽2009 | 20 | 19 193 | 23.2 (18.9–27.5) | 5 | 3 437 | 19.5 (8.3–30.8) | ||

| ⩾2010 | 32 | 123 640 | 22.6 (19.8–25.4) | 4 | 1 211 | 10.0 (3.7–16.2) | ||

| Country income | 0.001 | 0.53 | ||||||

| Low to middle | 13 | 5 089 | 34.4 (25.0–43.8) | 3 | 1 245 | 18.2 (1.7–34.8) | ||

| High | 39 | 137 744 | 19.4 (17.0–21.8) | 6 | 3 403 | 13.4 (8.2–18.7) | ||

| Selection bias | 0.11 | 0.55 | ||||||

| Low | 4 | 13 034 | 15.3 (11.2–19.3) | 2 | 1 284 | 22.8 (20.6–25.1) | ||

| Moderate | 34 | 28 376 | 22.1 (19.0–25.1) | 4 | 2 276 | 10.5 (5.5–15.6) | ||

| High | 14 | 101 423 | 27.5 (21.9–33.1) | 3 | 1 088 | 16.2 (1.1–31.4) | ||

| Attrition bias | 0.23 | – | ||||||

| Low | 41 | 122 748 | 24.4 (21.1–27.7) | 8 | 4 548 | 14.6 (8.1–21.2) | ||

| Moderate or high | 11 | 20 085 | 16.3 (13.3–19.2) | 1 | – | – | ||

| Postnatal (0–24 weeks) | ||||||||

| Publication year | 0.92 | 0.78 | ||||||

| ⩽2009 | 16 | 15 832 | 15.6 (12.8–18.3) | 4 | 26 657 | 8.1 (3.9–12.3) | ||

| ⩾2010 | 23 | 129 461 | 14.9 (13.3–16.6) | 5 | 1 838 | 10.8 (4.3–17.3) | ||

| Country income | 0.04 | – | ||||||

| Low to middle | 5 | 2 159 | 25.9 (13.7–38.1) | 1 | 871 | – | ||

| High | 34 | 143 134 | 13.7 (12.3–15.0) | 8 | 27 624 | 8.4 (5.3–11.5) | ||

| Selection bias | 0.60 | 0.57 | ||||||

| Low | 3 | 12 930 | 9.2 (4.7–13.8) | 1 | 871 | – | ||

| Moderate | 25 | 36 325 | 17.3 (14.2–20.5) | 6 | 27 225 | 8.2 (4.6–11.8) | ||

| High | 11 | 96 038 | 15.1 (12.0–18.2) | 2 | 399 | 4.4 (2.4–6.4) | ||

| Attrition bias | 0.41 | 0.91 | ||||||

| Low | 20 | 101 650 | 16.4 (13.5–19.3) | 7 | 28 096 | 9.9 (5.4–14.4) | ||

| Moderate | 15 | 37 971 | 17.3 (13.9–20.6) | 2 | 399 | 4.4 (2.4–6.4) | ||

| High | 4 | 5672 | 8.7 (5.8–11.6) | 0 | – | – | ||

Discussion

Main findings

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety. Included were 102 studies involving 221 974 women from 34 countries with 26 study authors providing additional information to promote the comprehensiveness and generalisability of the meta-analytic results. Overall, the prevalence rate for self-report anxiety symptoms in the first trimester was 18.2% increasing as the pregnancy progressed to 24.6% in the third trimester. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms across the three trimesters was 22.9%. Postnatally, 17.8% of women experienced significant anxiety symptoms in the first 4 weeks following childbirth but rates stabilised to approximately 15% thereafter. When diagnostic interviews were employed, the prevalence rate for any anxiety disorder during the first trimester was 18% decreasing marginally to approximately 15% in the final two trimesters of pregnancy. The prevalence of any anxiety disorder continued to decrease postnatally and ranged from 9.3 to 9.9% across the first year. As expected, rates for a generalised anxiety disorder were lower at 4% across the pregnancy and increased slightly to 4.2–5.7% postnatally. Overall, our findings demonstrate anxiety is a common mental health problem among pregnant and postpartum women internationally and that rates are significantly higher in this maternal population than in the general adult population. Reference Alonso, Lepine and Committee64,Reference Wittchen and Jacobi65

In interpreting the results, it is important to note that the majority of studies assessed anxiety using self-report instruments that measured anxiety symptoms rather than gold-standard diagnostic clinical interviews for various anxiety disorders. Although the sensitivity and specificity of these self-report instruments vary substantially, the most frequently used measure in this review was the STAI, a finding consistent with previous research. Reference Meades and Ayers66 Self-report measures do have limitations, such as potentially inflated prevalence estimates, but they also have high clinical utility in obstetric/midwifery, public health and primary care practices, where the majority of perinatal mental health problems are managed. Health professionals in these settings often have limited clinical expertise and time for diagnostic interviews and with research clearly suggesting informal surveillance misses at least 50% of cases, Reference Gavin, Gaynes, Lohr, Meltzer-Brody, Gartlehner and Swinson67 self-report measures are crucial for systematic case identification. To reflect the heterogeneity of the measures included in this meta-analysis, a range of prevalence estimates was reported in addition to a single estimate.

Prevalence rates in different countries

The varying prevalence rates between the included studies may further be attributed to diverse settings, recruitment strategies, inclusion and exclusion criteria, data-collection methods and follow-up time periods. Language or translation complexities and variations in conveying psychiatric symptoms are other potential methodological issues. Reference Bandelow and Michaelis68 However, there might also be real differences in prevalence rates because of cultural influences. This may partially explain the significantly higher self-reported anxiety rates found both antenatally and postnatally between low- to middle-income countries and high-income countries in this review. Whereas genetic and neurobiological determinants are probably evenly distributed among all women and are relevant aetiological factors, Reference Bandelow and Michaelis68 the distribution of anxiety may be different across cultures, supporting environmental influences in the aetiology of perinatal anxiety. Our results are consistent with another systematic review that found rates of ‘common perinatal mental disorders’ among World Bank categorised low- and middle-income countries were significantly greater than those reported in high-income countries. Reference Fisher, Cabral de Mello, Patel, Rahman, Tran and Holton69 Together, these findings challenge the idea that women's mental health is protected by culturally prescribed traditional postpartum rituals. There is also growing evidence that many risk factors for perinatal mental health in low- and middle-income countries may be influenced by conditions that transcend the woman's control. These risk factors include gender-based issues such as bias against female infants, restricted housework and infant care roles, and excessive unpaid workloads especially in multigenerational households. Reference Fisher, Cabral de Mello, Patel, Rahman, Tran and Holton69 Perinatal mental health in low- and middle-income countries has only recently started to receive attention partially because of previous priorities targeting maternal mortality. As such, in this review there were considerably more studies conducted in high-income countries than in low- to middle-income countries. High-quality research addressing perinatal mental health in low- and middle-income countries is warranted to guide clinical interventions and policies.

Prevalence rates over time

Although the media often portrays an increase in anxiety prevalence rates, there is no reliable evidence to support the notion that mental disorders in general are rising. Reference Kessler, Demler, Frank, Olfson, Pincus and Walters70,Reference Wittchen, Jacobi, Rehm, Gustavsson, Svensson and Jonsson71 This is consistent with our results where we found no difference in prevalence rates for anxiety symptoms or disorders between studies published before 2010 and those published afterwards. However, rates of mental health treatment seeking have increased and may be the reason for the general perception that anxiety is more prevalent. Reference Bandelow and Michaelis68 Despite improvements in treatment, anxiety remains undetected and untreated in the general population Reference Alonso, Angermeyer, Bernert, Bruffaerts, Brugha and Bryson72 and in perinatal women. To date, perinatal mental health research and clinical practice has disproportionately targeted depression with limited attention on anxiety. This is an important omission given a recent review indicating clinically relevant associations between antenatal anxiety and adverse child outcomes, with a 10 to 15% attributable risk of child behavioural problems related to antenatal anxiety and stress. Reference Glover14

Comorbid maternal depression and anxiety

The importance of comorbid maternal depression and anxiety has been highlighted in several studies. An Australian study found that a third of pregnant and postnatal women with major depression had comorbid anxiety. Reference Austin, Hadzi-Pavlovic, Priest, Reilly, Wilhelm and Saint73 In a US population-based study incorporating 4451 postpartum women, a third of women with anxiety symptoms also reported depressive symptoms. Reference Farr, Dietz, O'Hara, Burley and Ko74 Assessing comorbidity is important because research with non-postnatal populations has shown that comorbid depression and anxiety manifests into more severe symptoms with poorer acute and long-term outcomes, Reference Rivas-Vazquez, Saffa-Biller, Ruiz, Blais and Rivas-Vazquez75 is more difficult to treat than each disorder alone, Reference Emmanuel, Simmonds and Tyrer76 increases the risk for suicide Reference Fawcett77 and requires specific treatment strategies for both sets of symptoms. Reference Rivas-Vazquez, Saffa-Biller, Ruiz, Blais and Rivas-Vazquez75 The US Task Force for Prevention Screening now endorses screening for perinatal depression, Reference Siu, Bibbins-Domingo, Grossman, Baumann and Davidson78 however, not identifying anxiety symptoms as well underestimates the prevalence of mental health disorders and the need for perinatal mental health services. Matthey et al Reference Matthey, Barnett, Howie and Kavanagh79 suggests there is a ‘hierarchical diagnostic custom’ where depression takes precedence in clinical practice even when anxiety symptoms are a prominent feature. This focus on depression can result in individuals with anxiety (but without depression) being undetected and untreated.

Trait anxiety

Finally, trait anxiety, a condition clinically different from state anxiety symptoms, refers to the tendency to report negative emotions such as fears and worries across situations and is characterised by a stable perception of environmental stimuli as threatening. In this review, trait anxiety was high with prevalence rates ranging from 29 to 33% antenatally and decreasing to 23% postnatally. Although rarely examined, antenatal trait anxiety has been associated with increased risk for preterm birth among African American women. Reference Catov, Abatemarco, Markovic and Roberts80 If trait anxiety is an enduring maternal characteristic then its impact on the child is also likely to continue postnatally. This notion is supported in several studies. In a prospective US study with pregnant women, increasing trait anxiety was associated with poorer overall infant cognition. Reference Keim, Daniels, Dole, Herring, Siega-Riz and Scheidt81 In an Australian study, trait anxiety was a predictor of maternal report of difficult infant temperament at 4–6 months postpartum. Reference Austin, Hadzi-Pavlovic, Leader, Saint and Parker82 Further, a German study found trait anxiety was significantly correlated with impaired maternal bonding. Reference Dubber, Reck, Muller and Gawlik49 These results suggest that maternal trait anxiety may be as important as state anxiety symptoms or disorders and warrants further investigation. Antenatal psychological treatment interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy may optimise child outcomes. Reference Austin, Hadzi-Pavlovic, Leader, Saint and Parker82 Further, treating maternal trait anxiety may be an important step to determine whether reducing trait anxiety has a direct effect on preterm birth risk. Reference Catov, Abatemarco, Markovic and Roberts80

Implications

The prevalence of maternal anxiety in the antenatal and postnatal periods were estimated among 221 974 women from 34 countries. Results suggest anxiety across the perinatal period is highly prevalent and merits clinical attention similar to that given to perinatal depression. Prevalence rates were significantly higher in low- to middle-income countries possibly indicating cultural influences. The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease paradigm (DOHaD) Reference Heindel and Vandenberg83 suggests that human health and development have their origin in early life from conception to early childhood. During this period, the interplay between maternal and environmental factors programme fetal and child development through physiological changes that have long-lasting consequences on later health. Research to develop evidence-based interventions to reduce fetal and child exposure to risk factors such as perinatal anxiety is warranted in order to promote healthy child development.

Funding

We thank Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing of University of Toronto for providing the Tom Kierans International Postdoctoral Fellowship to K.F.-H.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following authors for providing additional data: Abiodun O. Adewuya, Reference Adewuya and Afolabi84 Mostafa Amr, Reference Amr and Hussein Balaha85 Marte Helene Bjørk, Reference Bjork, Veiby, Reiter, Berle, Daltveit and Spigset47 Alexa Bonacquisti, Reference Aaron, Bonacquisti, Geller and Polansky46 Birit F. P. Broekman, Reference Broekman, Chan, Chong, Kwek, Cohen and Haley13 Shayna Cunningham, Reference Rosenthal, Earnshaw, Lewis, Reid, Lewis and Stasko36 Deborah Da Costa, Reference Verreault, Da Costa, Marchand, Ireland, Dritsa and Khalife56 Janet DiPietro, Reference DiPietro, Costigan and Sipsma59 Natasa Jokic-Begic, Reference Jokic-Begic, Zigic and Nakic Rados54 Susan Garthus-Niegel, Reference Garthus-Niegel, von Soest, Knoph, Simonsen, Torgersen and Eberhard-Gran3 Fragiskos Gonidakis, Reference Gonidakis, Rabavilas, Varsou, Kreatsas and Christodoulou86 Wendy Hall, Reference Hall, Hauck, Carty, Hutton, Fenwick and Stoll5 Courtney Pierce Keeton, Reference Keeton, Perry-Jenkins and Sayer60 Sarah Keim, Reference Keim, Daniels, Dole, Herring, Siega-Riz and Scheidt81 Sheila W. McDonald, Reference McDonald, Kingston, Bayrampour, Dolan and Tough87 Barbara Menting, Reference Huizink, Menting, Oosterman, Verhage, Kunseler and Schuengel29 Khitam Mohammad, Reference Mohammad, Gamble and Creedy58 Chiara Pazzagli, Reference Bindt, Guo, Bonle, Appiah-Poku, Hinz and Barthel57 Chantal Razurel, Reference Razurel and Kaiser88 Patricia H. C. Rondó, Reference Rondo, Ferreira, Nogueira, Ribeiro, Lobert and Artes35 Annerine Roos, Reference Roos, Faure, Lochner, Vythilingum and Stein40 Anne-Laure Sutter-Dallay, Reference Sutter-Dallay, Giaconne-Marcesche, Glatigny-Dallay and Verdoux89 Heidi Stöckl, Reference Mahenge, Stockl, Likindikoki, Kaaya and Mbwambo90 Jan Taylor, Reference Taylor and Johnson91 Ana Amelia F. Vilela Reference Vilela, Pinto, Rebelo, Benaim, Lepsch and Dias-Silva37 and Vincenzo Zanardo. Reference Zanardo, Gasparetto, Giustardi, Suppiej, Trevisanuto and Pascoli92

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.