By definition, personality disorders are associated with a significant burden on the individuals with the disorder, those around them and on society in general. The probability of consulting and receiving effective treatment from psychiatric services varies according to demography, degree of disability and diagnosis (Reference Saarento, Rasanen and NieminenSaarento et al, 2000; Reference Andrews, Issakidis and CarterAndrews et al, 2001). Fewer individuals with a personality disorder make contact with psychiatric services compared with those with other conditions such as schizophrenia and depression (Reference Andrews, Issakidis and CarterAndrews et al, 2001) and their probability of withdrawing from treatment is considerably higher (Reference Percudani, Belloni and ContiniPercudani et al, 2002). We need to know more about the general distribution and prevalence of these disorders, the factors that influence their course and outcome, and their impact on new and existing mental health services, as well as on other services.

The decision to make personality disorder a separate diagnostic axis (Axis II) in the DSM–III classification increased research into these conditions. The current DSM–IV classification (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) includes ten categories of personality disorder, which can be divided into three clusters. Comparative epidemiological data are limited, as large-scale surveys of mental disorder have usually included only one category, antisocial personality disorder (Reference MoranMoran, 1999); all others were previously considered to have poor diagnostic reliability. Some surveys, mostly in the USA, have included the full range of categories of personality disorder to measure prevalence, but these have usually omitted clinical syndromes of mental disorder and are handicapped by reliance on self-report measures (Reference Reich, Yates and NduagubaReich et al, 1989; Reference Zimmerman and CoryellZimmerman & Coryell, 1989; Reference Bodlund, Ekselius and LinstromBodlund et al, 1993); clinical interviews (Reference Drake, Adler and VaillantDrake et al, 1988; Reference Samuels, Nestadt and RomanoskiSamuels et al, 1994); inclusion of telephone interviews (Reference Zimmerman and CoryellZimmerman & Coryell, 1989; Reference Black, Noyes and PfohlBlack et al, 1993; Reference Klein, Riso and DonaldsonKlein et al, 1995); small sample sizes (Reference Black, Noyes and PfohlBlack et al, 1993; Reference Klein, Riso and DonaldsonKlein et al, 1995); and unrepresentative samples such as students (Reference Lenzenweger, Loranger and KorfineLenzenweger et al, 1997), psychiatric patients’ relatives (Reference Zimmerman and CoryellZimmerman & Coryell, 1989; Reference Black, Noyes and PfohlBlack et al, 1993) and control groups from other studies (Reference Zimmerman and CoryellZimmerman & Coryell, 1989; Reference Maier, Lichtermann and KlingerMaier et al, 1992; Reference Black, Noyes and PfohlBlack et al, 1993; Reference Moldin, Rick and Erlenmayer-KimlingMoldin et al, 1994; Reference Klein, Riso and DonaldsonKlein et al, 1995). Surveys that have adopted stricter epidemiological criteria have used more restricted age ranges (Reference Samuels, Eaton and BienvenuSamuels et al, 2002) or been confined to urban areas (Reference Lenzenweger, Loranger and KorfineLenzenweger et al, 1997; Reference Torgersen, Kringlen and CramerTorgersen et al, 2001). Only two previous surveys have sampled an epidemiologically representative population and adjusted their estimates to provide an accurate reflection of population demography (Reference Torgersen, Kringlen and CramerTorgersen et al, 2001; Reference Samuels, Eaton and BienvenuSamuels et al, 2002), with the majority relying instead on unweighted samples (Table 1).

Table 1 Prevalence of personality disorders in community studies using structured clinical diagnostic instruments

| Study | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zimmerman & Coryell (Reference Zimmerman and Coryell1989) | Maier et al (Reference Maier, Lichtermann and Klinger1992) | Black et al (Reference Black, Noyes and Pfohl1993) | Moldin et al (Reference Moldin, Rick and Erlenmayer-Kimling1994) | Klein et al (Reference Klein, Riso and Donaldson1995) | Lenzenweger et al (Reference Lenzenweger, Loranger and Korfine1997) | Torgersen et al (Reference Torgersen, Kringlen and Cramer2001) | Samuels et al (Reference Samuels, Eaton and Bienvenu2002) | |

| Sample size, n | 797 | 452 | 247 | 302 | 229 | 258 | 2053 | 742 |

| Location | Iowa, USA | Mainz, Germany | Iowa, USA | New York, USA | New York, USA | New York, USA | Oslo, Norway | Baltimore, USA |

| Instrument | SIDP | SCID—II | SIDP | PDE | PDE | IPDE | SIDP | IPDE |

| Diagnostic system | DSM—III | DSM—III—R | DSM—III | DSM—III—R | DSM—III—R | DSM—III—R | DSM—III—R | DSM—IV |

| Sample (method) | Relatives of patients and normal controls | Normal controls, their partners, and relatives | Relatives of obsessive—compulsive and normal control probands | Normal controls, parents and their children | Relatives of normal controls | University students age 18-19 years (two-stage procedure) | Individuals from National Register (weighted data) | Individuals reinterviewed from previous survey, aged 34-94 years (weighted data) |

| Personality disorder: prevalence, % | ||||||||

| Paranoid | 0.9 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 2.4 | 0.7 |

| Schizoid | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 0.9 |

| Schizotypal | 2.9 | 0.7 | 3.2 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Antisocial | 3.3 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 4.1 |

| Borderline | 1.6 | 1.1 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Histrionic | 3.0 | 1.3 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 0.2 |

| Narcissistic | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.9 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.03 |

| Avoidant | 1.3 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 5.2 | 0.4 | 5.0 | 1.8 |

| Dependent | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.1 |

| Obsessive—compulsive | 2.0 | 2.2 | 9.3 | 0.7 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.9 |

| Passive—aggressive | 3.3 | 1.8 | 10.5 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 1.7 | |

| Self-defeating | 0.0 | 0.8 | ||||||

| Sadistic | 0.2 | |||||||

| Any | 14.31 | 10.0 | 22.31 | 7.3 | 14.8 | 3.92 | 13.4 | 9.0 |

We therefore estimated the prevalence of individual categories of personality disorder using the DSM–IV system, the associations between personality disorder and demographic characteristics, co-occurring mental (Axis I) disorders, and use of clinical and institutional services, in a two-phase survey of a representative sample of adults aged 16–74 years in Great Britain, conducted in 2000.

METHOD

Sample

The sample was drawn from those participating in the British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity, aged 16–74 years and living in private households in England, Wales or Scotland (Reference Singleton, Bumpstead and O'BrienSingleton et al, 2001). This was a two-phase survey (Reference Shrout and NewmanShrout & Newman, 1989). In phase I, participants completed computer-assisted interviews with Office for National Statistics interviewers, in an interview lasting on average 1½ h. The Royal Mail's small users Postcode Address File was used as the sampling frame for private households. Postcode sectors were stratified within each National Health Service region on the basis of socio-economic profile. Initially, 438 postal sectors were selected with a probability proportional to size, i.e. the number of delivery points. Postal sectors contain on average 2550 of these. Within each of these sectors, 36 were selected, yielding a sample of 15 804 delivery points. These were visited to identify private households with at least one person aged 16–74 years. The Kish grid method (Reference KishKish, 1965) was used to select systematically one person in each household.

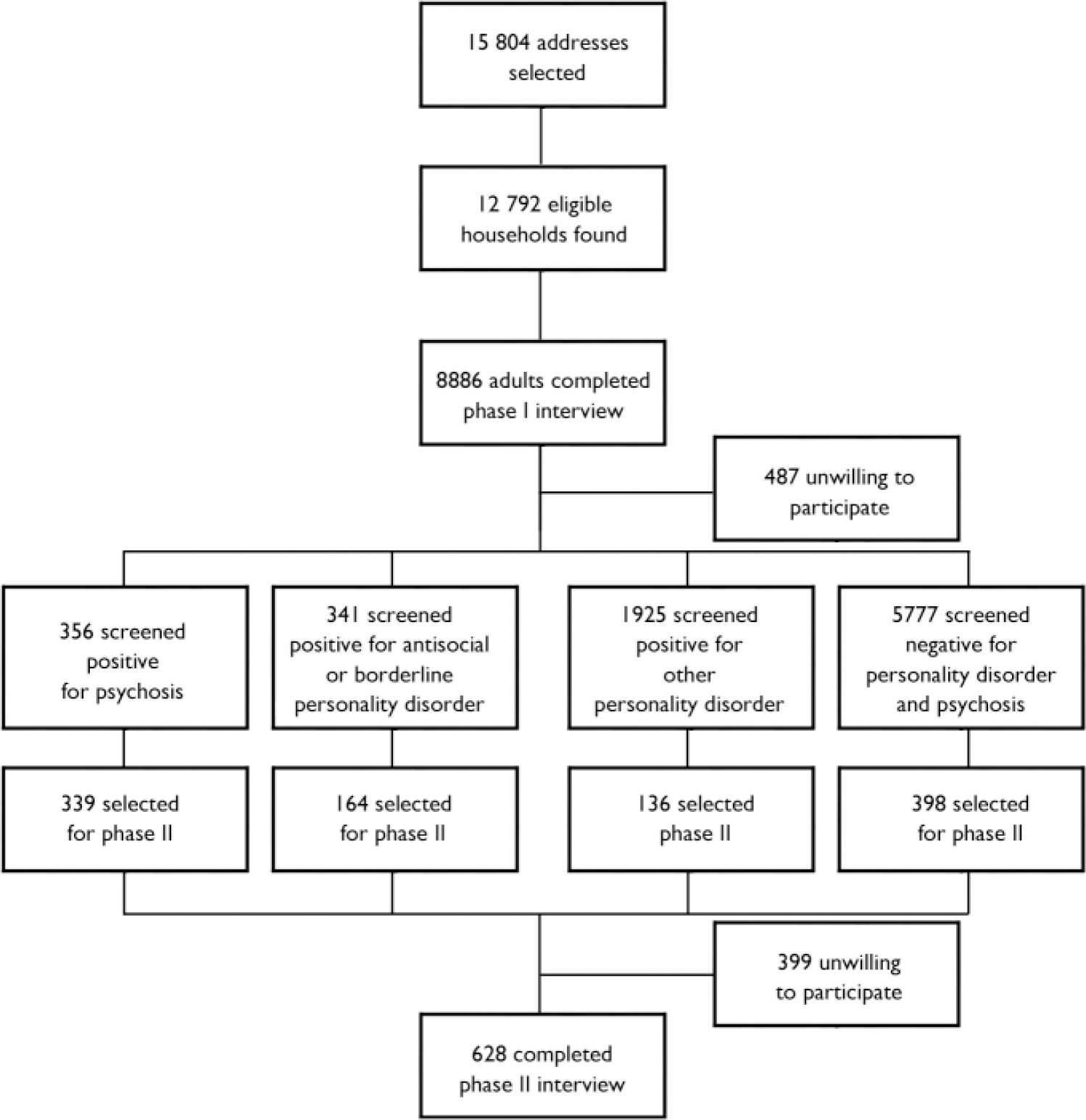

A total of 8886 adults completed a first-phase interview, a response rate of 69.5%. Respondents who completed the initial interview were asked whether they would be willing to be contacted, if selected, to take part in the second phase. The phase II sample was then drawn on the basis of scores on two self-report diagnostic instruments (Fig. 1), to include:

Fig. 1 Sampling procedure for two-phase survey.

-

(a) all who satisfied one or more of the sift criteria for psychotic disorder, regardless of whether they sifted positive for personality disorder as well;

-

(b) half of those who sifted positive for antisocial and borderline personality disorder, with no evidence of psychotic disorder;

-

(c) one in 14 of those who sifted positive for other personality disorders, with no evidence of psychotic disorder;

-

(d) one in 14 of those who showed no evidence of either psychosis or personality disorder.

Of those selected for the second phase, 638 (61.6%) agreed to participate and were interviewed by seven graduate psychologists who had received training and clinical experience extending over a month in the use of the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN; Reference Wing, Babor and BrughaWing et al, 1990; World Health Organization Division of Mental Health, 1999) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis II disorders (SCID–II; Reference First, Gibbon and SpitzerFirst et al, 1997). They were supervised throughout the fieldwork period by an experienced field manager to provide quality assurance and standardisation.

Compared with the respondents, those who refused an interview had significantly different demographic characteristics: they were less likely to be White (2.9% v. 8.5%, P=0.001), more likely to have no educational qualification (39.7% v. 31.0%, P=0.004), less likely to have a degree (9.7% v. 16.0%, P=0.004), and more likely to be of lower social class (31.3% v. 22.2%, P<0.001) and to be living in rented accommodation (43.1% v. 33.9%, P=0.003). These differences were taken into account in the weighting procedure. Other background factors, including age, gender, legal marital status, employment status and family type, were similar in respondents and non-respondents.

Measurement of personality disorder and mental disorder

Possible cases of personality disorder were identified in the first phase using the screening questionnaire of SCID–II (Reference First, Gibbon and SpitzerFirst et al, 1997). Participants gave ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses to 116 questions which they entered themselves on a laptop computer. Categories of Axis II disorder derived from this instrument were created by applying algorithms developed using data obtained using the Structured Clinical Interview administered by trained interviewers in a previous survey of prisoners (Reference Singleton, Meltzer and GatwardSingleton et al, 1998). In the analysis of that survey, the cut-off points were manipulated in order to increase levels of agreement, measured by the kappa coefficient, between both individual criteria and diagnoses measured in the initial screening questionnaire and the subsequent clinical interviews. This allowed diagnoses to be obtained from the self-completion self-completion instrument. The sensitivity and specificity of the SCID–II screen for personality disorder ranged from 0.62 to 1.0 and from 0.88 to 1.0 respectively.

Participants were also screened for the indications of psychotic disorder in the first-phase interview. The following criteria were considered indicative of possible psychosis: a positive response to the section in the Psychosis Screening Questionnaire (Reference Bebbington and NayaniBebbington & Nayani, 1994) relating to auditory hallucinations; self-report of having received a diagnosis of psychosis or of psychotic symptoms in the health section of the interview; receipt of antipsychotic medication; and having had an in-patient stay in a mental hospital or ward. Fulfilment of any of these criteria determined selection for a second-phase interview, in which psychotic disorder was assessed using the SCAN. In addition, affective and anxiety disorders (including generalised anxiety disorder, mixed anxiety and depression disorder, depressive episode, phobias, obsessive–compulsive disorder and panic disorder) in the week preceding interview were assessed in the first phase using the revised version of the Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS–R; Reference Lewis and PelosiLewis & Pelosi, 1990). A positive response to one or more of these conditions was combined into a single category of affective/anxiety disorder. The principal instrument to assess alcohol misuse was the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Reference Babor, de la Fuente and SaundersBabor et al, 1992), which defines hazardous alcohol use as an established pattern of drinking which brings the risk of physical and psychological harm over the year before interview. Prevalence of alcohol dependence in the previous 6 months was assessed using the Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SAD–Q; Reference Stockwell, Murphy and HodgsonStockwell et al, 1983). A number of questions designed to measure drug use were included in the phase I interviews. Positive response, for a series of different substances, to any of five questions to measure drug dependence over the past year were included (Reference Singleton, Bumpstead and O'BrienSingleton et al, 2001).

For the purpose of this study, four combined categories of clinical syndromes were used: psychotic disorders over the previous 12 months assessed as present, using the SCAN in phase II and combined into a single category, ‘functional psychosis’; measures obtained in phase I of ‘hazardous drinking’ from self-report, using the AUDIT; a combined category of ‘any’ drug dependence; and ‘any’ affective/anxiety disorder identified with the CIS–R.

Questions were included in phase I on self-reported healthcare service use, criminal justice involvement, and placement in local authority and institutional care in childhood.

Statistical analysis

To estimate the prevalence of personality disorder in the population in Great Britain, weights were used to adjust for the effects of the differential probabilities of selection and non-response in both phases of the survey. In the second phase, the information from phase I was used to group people into weighting classes and non-response weights were calculated accordingly (Fig. 1). To control for effects of selecting one individual per household and for underrepresentation of any subgroups according to national demography, it was necessary to adjust variance estimates and to account for any deviations from selecting a simple random sample. The weighting procedure therefore took into account respondents’ relative chances of selection, non-response and also selection bias with respect to age, gender and region. This analysis is based on the 626 persons who completed both a second-phase SCID–II and a scan interview, so the weighting takes account of varying probabilities of selection and non-response at both stages.

Details of the procedures used in constructing the weighting variables have been given by Singleton et al (Reference Singleton, Bumpstead and O'Brien2001). As would be expected, comparisons between unweighted and weighted prevalences of personality disorder, based on the second-phase sample, showed considerable differences. Weighted analysis was performed throughout this study. The weighted prevalences and their confidence intervals were calculated by means of the SVYTAB procedure in Stata version 7.0.

As in DSM–IV, we have grouped the personality disorders into three clusters: cluster A disorders (the ‘odd–eccentric’ group, including paranoid, schizoid and schizotypal categories), cluster B disorders (the flamboyant, dramatic–emotional or erratic group, including the antisocial, borderline, histrionic and narcissistic categories) and cluster C disorders (the anxious–fearful group, including avoidant, dependent and obsessive–compulsive categories). The weighted prevalence of each of these clusters was compared across demographic characteristics. For each of the variables under consideration, Pearson's χ2 statistic corrected for the survey design was used to test the difference of prevalence between category groups of the factors. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 11.0 was used for this analysis.

Weighted multilevel multivariate logistic regression (Reference Yang, Heath and GoldsteinYang et al, 2000) was used to analyse the association between the clusters and each of the Axis I mental disorder categories, to take into account both the high level of comorbidity between personality disorders by estimating the residual correlation between clusters, and the post-stratification effect by allowing random effects across the Postcode Address File areas. The multilevel logistic model was used for the association between service uses and each cluster. The same adjustments on age, gender, marital status and social class were made. The statistical package MLwiN (version 1.10; Reference Rasbash, Browne and GoldsteinRasbash et al, 2000) was used for the models.

All statistical software was for Windows.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study sample and the subgroup with personality disorder

The study sample comprised 626 participants following weighting. Of these, 355 (56.7%) were female, 608 (97.1%) were White and 416 (66.5%) came from urban areas (Table 2). Nearly half the sample were married or cohabiting, just over a quarter were single and one in seven were divorced. Two-thirds of the sample were home owner-occupiers. Respondents with any personality disorder were more likely to be male, older, separated or divorced, unemployed or economically inactive, of lower social class, living in rented accommodation and living in an urban area.

Table 2 Socio-demographic and socio-economic characteristics of sample (n=626) and participants with any personality disorder

| Prevalence: any personality disorder | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents n (%) | Unweighted (%) | Weighted % (95% CI) | |

| Age group | |||

| 16-34 years | 167 (26.7) | 11.4 | 3.4 (1.5-7.2) |

| 35-54 years | 284 (45.4) | 12.3 | 4.4 (2.5-7.4) |

| 55-74 years | 175 (27.9) | 7.4 | 5.8 (2.3-13.6) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 271 (43.3) | 13.3 | 5.4 (3.2-9.1) |

| Female | 355 (56.7) | 8.7 | 3.4 (1.7-6.7) |

| Ethnic origin | |||

| White | 608 (97.1) | 10.5 | 4.5 (2.8-6.8) |

| Other | 18 (2.9) | 16.7 | 2.6 (0.6-10.3) |

| Legal marital status | |||

| Married/cohabiting | 299 (47.8) | 8.0 | 4.1 (2.1-7.9) |

| Separated | 33 (5.3) | 24.2 | 14.2 (3.7-41.7) |

| Single | 176 (28.1) | 9.1 | 1.9 (1.0-3.7) |

| Divorced | 90 (14.4) | 20.0 | 14.5 (7.2-27.2) |

| Widowed | 28 (4.5) | 3.6 | 0.4 (0-2.8) |

| Educational qualifications | |||

| Any qualification | 432 (69.0) | 9.3 | 4.3 (2.4-7.3) |

| No qualification | 194 (31.0) | 13.9 | 4.7 (2.6-8.6) |

| Employment status | |||

| Working full-time | 265 (42.3) | 6.4 | 3.2 (1.6-6.4) |

| Working part-time | 103 (16.5) | 4.9 | 1.1 (0.4-3.2) |

| Unemployed | 20 (3.2) | 35.0 | 15.5 (4.8-39.9) |

| Economically inactive | 238 (38.0) | 16.0 | 7.4 (3.8-13.6) |

| Social class1 | |||

| I | 33 (5.3) | 9.1 | 6.4 (1.1-29.9) |

| II | 181 (28.9) | 7.2 | 3.7 (1.4-10.0) |

| IIINM | 151 (24.1) | 8.6 | 2.0 (0.9-4.3) |

| IIIM | 103 (16.5) | 10.7 | 3.3 (1.4-7.6) |

| IV | 92 (14.7) | 18.5 | 10.8 (4.7-16.7) |

| V | 42 (6.7) | 16.7 | 5.6 (1.7-16.7) |

| Armed Forces | 2 (0.3) | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Housing tenure | |||

| Owned outright | 135 (21.6) | 4.4 | 2.0 (0.4-9.1) |

| Owned with mortgage | 278 (44.4) | 7.2 | 3.1 (1.5-6.1) |

| Rented from LA or HA | 167 (26.7) | 21.6 | 12.2 (6.6-21.3) |

| Rented from other source | 45 (7.2) | 8.9 | 2.3 (0.4-12.4) |

| Type of area | |||

| Urban | 416 (66.5) | 13.0 | 5.2 (3.2-8.5) |

| Semi-rural | 148 (23.6) | 7.4 | 3.4 (1.5-7.5) |

| Rural | 62 (9.9) | 3.2 | 1.7 (0.2-5.6) |

| Base | 626 (100.0) | 10.7 | 4.4 (2.9-6.7) |

Prevalence of personality disorders

The unweighted prevalences of personality disorders from the second stage of the survey showed that 10.7% of the sample (4.4% weighted) had at least one DSM–IV disorder, with men more likely to have a disorder (13.3%; weighted 5.4%) compared with women (8.7%; weighted 3.4%) (Table 2). All personality disorder categories were more prevalent in men, apart from the schizotypal category. The weighted prevalences of individual disorders were between 0.06% and 1.9%, but there was no case of narcissistic or histrionic disorder identified among those sampled in the survey. After weighting, the most prevalent personality disorder was the obsessive–compulsive type (1.9%), with dependent and schizotypal disorders being the least frequent (weighted 0.06%) (Table 3).

Table 3 Prevalence of personality disorder from clinical interviews, according to gender

| Personality disorder | Male | Female | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Weighted prevalence % (95% CI) | n | Weighted prevalence % (95% CI) | n | Weighted prevalence % (95% CI) | |

| Paranoid | 9 | 1.2 (0.4-3.1) | 6 | 0.3 (0.1-1.0) | 15 | 0.7 (0.3-1.7) |

| Schizoid | 5 | 0.9 (0.3-2.6) | 2 | 0.8 (0.2-3.5) | 7 | 0.8 (0.3-1.7) |

| Schizotypal | 1 | 0.02 (0.0-0.1) | 1 | 0.1 (0.03-0.3) | 4 | 0.06 (0.02-0.2) |

| Cluster A | 13 | 2.0 (0.9-4.2) | 10 | 1.1 (0.4-3.3) | 23 | 1.6 (0.8-2.9) |

| Antisocial | 11 | 1.0 (0.5-2.1) | 3 | 0.2 (0.05-0.7) | 14 | 0.6 (0.3-1.1) |

| Borderline | 9 | 1.0 (0.3-3.2) | 7 | 0.4 (0.2-1.1) | 16 | 0.7 (0.3-1.7) |

| Cluster B 1 | 19 | 2.0 (1.0-3.9) | 8 | 0.5 (0.2-1.2) | 27 | 1.2 (0.7-2.2) |

| Avoidant | 9 | 1.0 (0.3-2.8) | 12 | 0.7 (0.3-1.8) | 21 | 0.8 (0.4-1.7) |

| Dependent | 2 | 0.2 (0.04-1.0) | 1 | 0.02 (0.0-0.2) | 3 | 0.1 (0.03-0.5) |

| Obsessive—compulsive | 7 | 2.6 (1.0-6.6) | 6 | 1.3 (0.3-5.6) | 13 | 1.9 (0.9-4.3) |

| Cluster C | 16 | 3.2 (1.5-7.0) | 18 | 2.0 (0.7-5.4) | 34 | 2.6 (1.4-4.8) |

| Any personality disorder | 36 | 5.4 (3.2-9.1) | 31 | 3.4 (1.7-6.7) | 67 | 4.4 (2.9-6.7) |

| Personality disorder unspecified2 | 14 | 4.8 (2.3-7.3) | 20 | 6.6 (3.8-9.4) | 34 | 5.7 (3.8-7.6) |

The mean number of personality disorder diagnoses among those who qualified for such a diagnosis was 1.92; of these, 53.5% had one disorder only, with 21.6% having two, 11.4% having three and 14.0% having between four and eight diagnoses. Classification of personality disorder by cluster showed cluster C to be the most frequent (2.6% weighted), with cluster A (1.6% weighted) and cluster B (weighted 1.2%) less prevalent. The weighted prevalence of antisocial personality disorder was five times greater in men (1.0%) than in women (0.2%).

Association with demographic characteristics

Table 4 shows that cluster A disorders were more common in participants who were separated or divorced, unemployed with a low weekly income and of lower social class; cluster B disorders were more prevalent in younger age groups, in men, separated or divorced people, those of lower social class and those renting their accommodation; cluster C disorders showed no individual association with demographic characteristics apart from employment status, where more were economically inactive.

Table 4 Weighted prevalence of personality disorder by demographic characteristics

| Demographic characteristic | Weighted prevalence | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster A disorders | Cluster B disorders | Cluster C disorders | ||||||||||

| % | χ2 | d.f. | P | % | χ2 | d.f. | P | % | χ2 | d.f | P | |

| Age group | 1.00 | 2 | 0.36 | 3.33 | 2 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 2 | 0.82 | |||

| 16-34 years | 4.6 | 5.6 | 4.9 | |||||||||

| 35-54 years | 2.5 | 5.6 | 5.7 | |||||||||

| 55-74 years | 2.3 | 0.0 | 4.2 | |||||||||

| Gender | 1.52 | 1 | 0.22 | 8.12 | 1 | 0.005 | 1.61 | 1 | 0.20 | |||

| Male | 4.1 | 6.8 | 6.3 | |||||||||

| Female | 2.3 | 2.0 | 4.0 | |||||||||

| Ethnic origin | 0.37 | 1 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.62 | 0.60 | 1 | 0.44 | |||

| White | 1.7 | 1.2 | 2.6 | |||||||||

| Other | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||||||||

| Legal marital status | 3.27 | 2 | 0.04 | 3.00 | 2 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 2 | 0.43 | |||

| Married or widowed | 2.0 | 2.7 | 5.4 | |||||||||

| Separated or divorced | 7.5 | 9.0 | 7.1 | |||||||||

| Single | 3.6 | 5.4 | 3.5 | |||||||||

| Educational qualifications | 4.24 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.81 | 2.15 | 1 | 0.14 | |||

| Any qualification | 0.9 | 1.1 | 3.1 | |||||||||

| No qualification | 3.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 | |||||||||

| Employment status | 6.83 | 3 | 0.0003 | 2.17 | 3 | 0.09 | 4.08 | 3 | 0.007 | |||

| Working full-time | 0.8 | 3.5 | 2.3 | |||||||||

| Working part-time | 1.8 | 2.1 | 4.5 | |||||||||

| Unemployed | 18.7 | 14.3 | 0.0 | |||||||||

| Economically inactive | 5.6 | 5.7 | 9.7 | |||||||||

| Social class | 2.63 | 5 | 0.02 | 2.47 | 5 | 0.02 | 0.64 | 5 | 0.70 | |||

| I | 0.0 | 2.0 | 4.1 | |||||||||

| II | 0.5 | 2.3 | 4.0 | |||||||||

| IIINM | 1.0 | 2.5 | 4.0 | |||||||||

| IIIM | 5.2 | 4.8 | 5.4 | |||||||||

| IV | 7.1 | 11.6 | 9.1 | |||||||||

| V | 5.9 | 4.4 | 6.3 | |||||||||

| Housing tenure | 3.52 | 1 | 0.06 | 18.3 | 1 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 1 | 0.26 | |||

| Owned | 2.2 | 1.9 | 4.3 | |||||||||

| Rented | 4.9 | 9.4 | 6.4 | |||||||||

| Type of area | 0.63 | 2 | 0.50 | 0.19 | 2 | 0.78 | 1.50 | 2 | 0.22 | |||

| Urban | 3.4 | 4.5 | 5.7 | |||||||||

| Semi-rural | 3.5 | 4.6 | 5.3 | |||||||||

| Rural | 0.8 | 2.6 | 0.0 | |||||||||

| Weekly gross income | 3.48 | 3 | 0.016 | 0.26 | 3 | 0.85 | 1.54 | 3 | 0.20 | |||

| Under £100 | 5.5 | 4.9 | 4.7 | |||||||||

| £100-£200 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 7.7 | |||||||||

| £200-£400 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 2.7 | |||||||||

| £400 and over | 0.0 | 5.1 | 3.8 | |||||||||

Axis comorbidity

There was a high level of comorbidity between personality disorder categories in different clusters. For example, 6 (32%) participants with cluster A disorder had a cluster B disorder, compared with 20 (3%) with no cluster A disorder (OR=12.95, 95% CI 4.31–38.89; P<0.001); 9 (48%) with cluster A disorder had a cluster C disorder, compared with 22 (4%) with no cluster A disorder (OR=23.96, 95% CI 8.64–66.47; P<0.001). Similarly, 7 (27%) participants with cluster C disorder had a cluster B disorder, compared with 24 (4%) with no cluster C disorder (OR=8.56, 95% CI 3.01–24.36; P<0.001). Cramer's correlation coefficient was 0.25 for comorbidity between cluster A and cluster B disorders, 0.29 for that between cluster A and cluster C, and 0.16 between cluster B and cluster C.

There were clear associations between the individual clusters of personality disorder and mental disorder (Table 5). After adjustments for gender, age, social class and marital status, cluster B disorders were associated with both functional psychosis and affective/anxiety disorders, and cluster C disorders were associated with affective/anxiety disorders, but demonstrated a negative association with hazardous drinking.

Table 5 Weighted multilevel multivariate logistic regression analysis of association between personality disorder cluster and mental disorder: estimated odds ratio, models adjusted for gender, age, social class and marital status

| Mental disorder | Cluster A OR (95% CI) | Cluster B OR (95% CI) | Cluster C OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional psychosis | 2.83 (0.59-13.6) | 7.44 (2.20-25.2)** | 2.52 (0.66-9.54) |

| Affective/anxiety disorder | 2.70 (0.99-7.34) | 20.3 (5.70-71.6)*** | 4.21 (1.93-8.80)* |

| Alcohol dependence | 1.61 (0.45-5.71) | 4.21 (1.69-10.5)* | 0.46 (0.10-2.13) |

| Hazardous drinking | 0.83 (0.29-2.42) | 1.51 (0.65-3.48) | 0.36 (0.13-0.99)* |

| Drug dependence | 1.32 (0.22-7.76) | 1.87 (0.57-6.11) | 1.93 (0.53-7.07) |

Reported use of health services and other agencies

The unadjusted analyses showed strong associations between consultations in primary care, attendance for counselling services, and psychiatric admission for those with a personality disorder, but after adjustment most of these associations disappeared (Table 6). However, those with cluster A disorders were three times more likely to have been in local authority care before the age of 16 years; those with cluster B disorders were more likely to have had a criminal conviction, to have spent time in prison and have been in local authority or institutional care; those with cluster C disorders were more likely to have received psychotropic medication and counselling (Table 6).

Table 6 Weighted multilevel logistic regression analysis of association between personality disorder clusters and service use: estimated odds ratios of unadjusted and adjusted models

| Service use | Cluster A | Cluster B | Cluster C | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted1 | Unadjusted | Adjusted1 | Unadjusted | Adjusted1 | |||||||

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| GP consultation (psychological problems) | 3.72 | (1.46-9.51)** | 1.25 | (0.31-5.07) | 4.63 | (1.95-10.90)*** | 1.40 | (0.39-5.02) | 4.10 | (1.88-8.96)*** | 2.04 | (0.73-5.81) |

| Psychiatric consultation (secondary/tertiary care) | 2.25 | (0.33-15.30) | 0.50 | (0.08-3.06) | 6.54 | (0.62-69.50) | 2.64 | (0.23-30.80) | 2.03 | (0.39-10.70) | 0.67 | (0.11-3.92) |

| Community care service | 1.19 | (0.41-3.43) | 0.38 | (0.09-1.70) | 2.69 | (0.92-7.84) | 0.73 | (0.22-2.44) | 3.08 | (1.37-6.94)** | 1.45 | (0.49-4.26) |

| Psychotropic medication | 3.77 | (1.37-10.30)* | 0.85 | (0.18-3.97) | 3.22 | (1.11-9.35)* | 0.70 | (0.15-3.38) | 7.23 | (3.15-12.60)*** | 3.06 | (1.08-8.62)* |

| Counselling | 1.76 | (1.28-2.42)*** | 1.26 | (0.73-2.20) | 1.74 | (1.23-2.46)** | 1.05 | (0.61-1.83) | 2.34 | (1.76-3.10)*** | 1.86 | (1.26-2.73)** |

| Psychiatric admission | 3.46 | (1.34-8.86)* | 1.19 | (0.20-7.13) | 2.08 | (0.86-5.00) | 1.05 | (0.25-4.42) | 3.13 | (1.44-6.80)*** | 1.91 | (0.62-5.85) |

| Criminal conviction | 1.64 | (0.54-5.04) | 0.61 | (0.15-2.54) | 12.90 | (5.30-31.20)*** | 10.6 | (2.72-41.3)*** | 1.28 | (0.46-3.57) | 0.56 | (0.18-1.70) |

| Period in prison | 3.79 | (0.51-15.90) | 1.37 | (0.29-6.36) | 12.40 | (4.20-36.20)*** | 7.57 | (1.01-56.6)* | 1.55 | (0.30-7.94) | 0.24 | (0.03-1.70) |

| Local authority care (before age 16 years) | 2.88 | (1.35-6.14)** | 3.18 | (1.14-8.83)* | 3.07 | (1.33-7.11)** | 6.00 | (1.77-20.4)* | 1.25 | (0.58-2.70) | 1.45 | (0.53-4.01) |

| Institutional care (before age 16 years) | 4.87 | (1.59-14.90)** | 2.53 | (0.53-12.2) | 16.20 | (6.12-43.10)*** | 18.0 | (3.87-83.8)*** | 2.67 | (0.85-8.35) | 1.01 | (0.24-4.29) |

DISCUSSION

Comparison with previous surveys

This survey, the first to report on the prevalence and correlates of personality disorders in a large national sample in Great Britain, demonstrates that a substantial number of people in the general household population have a personality disorder. The high level of comorbidity of these disorders (mean number 1.92) is higher than the level of 1.48 found in a Norwegian study (Reference Torgersen, Kringlen and CramerTorgersen et al, 2001), but is lower than that found in clinical populations (Reference Alnaes and TorgersenAlnaes & Torgersen, 1988; Reference ZimmermanZimmerman, 1994). Nevertheless, the prevalence of personality disorder in our study (4.4%) is lower than that found in nearly all previous surveys which have used structured clinical interviews, conducted in other countries. These rates have ranged from 3.9% to 22.3% (Reference Zimmerman and CoryellZimmerman & Coryell, 1989; Reference Maier, Lichtermann and KlingerMaier et al, 1992; Reference Black, Noyes and PfohlBlack et al, 1993; Reference Moldin, Rick and Erlenmayer-KimlingMoldin et al, 1994; Reference Klein, Riso and DonaldsonKlein et al, 1995; Reference Lenzenweger, Loranger and KorfineLenzenweger et al, 1997; Reference Torgersen, Kringlen and CramerTorgersen et al, 2001; Reference Samuels, Eaton and BienvenuSamuels et al, 2002). Differences between prevalence rates in different studies may be explained by differences in sampling procedures, diagnostic instruments and number of disorder categories included, rather than true differences between populations (see Table 1). All studies in this field are handicapped by the poor diagnostic reliability of personality disorder and its poor temporal stability (Reference ZimmermanZimmerman, 1994). For example, following recalculation, the prevalence among university students in New York fell from 6.7% to 3.9% when cases of personality disorder ‘not otherwise specified’ were removed from the analysis to make it compatible with diagnoses included in other surveys (Reference Lenzenweger, Loranger and KorfineLenzenweger et al, 1997). Similarly, passive–aggressive personality disorder, included in certain earlier studies, was removed from the DSM–IV glossary. Studies using this system included fewer categories. Nevertheless, sampling may have had a greater impact on the earlier studies, which were mainly conducted in the USA. Most were opportunistic, examining prevalences in comparison groups from local communities which had been included in other experimental studies. Some included controls, or even the relatives of the psychiatric patients, from the original study. The latter would be expected to have a high prevalence of psychiatric morbidity, including personality disorder. Only the populations of Oslo (Reference Torgersen, Kringlen and CramerTorgersen et al, 2001) and Baltimore (Reference Samuels, Eaton and BienvenuSamuels et al, 2002) were prospectively surveyed with the intention of measuring the prevalence of personality disorder in a representative sample. The low prevalence found in Britain when compared with these surveys requires further explanation.

A series of factors are likely to have led to these differences. Both the Baltimore and Oslo surveys were conducted in urban locations, whereas our survey covered a wider range of locations, but found a higher prevalence of personality disorder in British urban areas. The findings of the Baltimore study for individual categories of personality disorder were closest to our own findings for all categories except antisocial disorder. Table 1 demonstrates that surveys in the USA have consistently found higher prevalences of antisocial personality disorder than European surveys, except for a survey in Iowa which included relatives of patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder and which demonstrated high prevalences of passive–aggressive and obsessive–compulsive personality disorders. Antisocial personality disorder is especially prevalent in US inner-city locations (Reference Robins, Tipp, Przybeck, Robbins and RegierRobins et al, 1991) and contributed to the finding of an overall prevalence of personality disorder in Baltimore twice that in Great Britain. However, the differences between Oslo and Britain, both European countries, are more difficult to explain. The Oslo survey included the largest sample, selected participants on the basis of a national register, was not a two-phase survey and had a relatively low rate of attrition. The survey included provisional categories of self-defeating and sadistic disorders, as well as passive–aggressive disorder, which were excluded from DSM–IV. These additional categories are likely to have increased the overall prevalence in Oslo. Higher prevalences of certain personality disorders in the Norwegian survey could reflect cultural differences. Table 1, however, demonstrates that surveys using the Structured Interview for DSM–III–R Personality (SIDP; Reference Pfohl, Blum and ZimmermanPfohl et al, 1989) found consistently high prevalences. This questions whether the diagnostic threshold for personality disorder is lower when using this instrument and leads to false-positive findings. The SIDP may be unsuitable for future epidemiological study, as the face validity of findings that one in every seven adults in Oslo and one in every five in Iowa have a disorder of personality is questionable.

We have been able to report robust findings that replicate other work. Cluster C personality disorders are more prevalent than those in clusters A and B, and all personality disorders appear to be more prevalent in men than in women. People with a personality disorder are much more likely to be unemployed or economically inactive and less likely to own their own accommodation, compared with those who do not have such a disorder. Cluster B disorders become less common with increasing age, but this is not shown to occur with the other clusters, and people who are separated and divorced have a higher prevalence of personality disorders than others. These findings receive some support from studies in clinical populations, which have also shown an improvement in cluster B disorders over time (Reference Seivewright, Tyrer and JohnsonSeivewright et al, 2002) and a higher level of contact with clinical services (Reference Bender, Dolan and SkodolBender et al, 2001; Reference Jackson and BurgessJackson & Burgess, 2004), and the associations of cluster B disorders with psychoses and cluster B and C disorders with neurotic disorders are also similar (Reference Reich, Perry and SheraReich et al, 1994; Reference Moran, Walsh and TyrerMoran et al, 2003).

Limitations

The sample interviewed was restricted to general households and did not include people in psychiatric institutions, the homeless or those in prison. A survey among prisoners in England and Wales which used the same research diagnostic instruments demonstrated a very high prevalence of personality disorder, especially the antisocial category (Reference Singleton, Meltzer and GatwardSingleton et al, 1998). Nevertheless, Robins et al (Reference Robins, Tipp, Przybeck, Robbins and Regier1991) have pointed out that the overwhelming majority of people with antisocial personality disorder at any one time are in the community. On the other hand, our sample size in the second phase was not sufficient to detect respondents with rater categories of disorder, such as narcissistic and histrionic personality disorder. Samuels et al (Reference Samuels, Eaton and Bienvenu2002) argued that progress in understanding the epidemiology of abnormal personality would benefit from studying greater numbers of people with specific personality disorders, either by sampling a larger number or by the development of better screening instruments to enrich the sample for specific disorders (see Reference Lenzenweger, Loranger and KorfineLenzenweger et al, 1997).

The first-phase sample compared favourably with other surveys in terms of the response rate, but the two-phase method inevitably led to further attrition in the second phase, leading to additional adjustments to the prevalences of personality disorder through the weighting procedure. However, the weighting procedure may not have ultimately eliminated response bias due to attrition.

Personality disorder in this survey was measured only on the basis of face-to-face interviews with participants and did not include information from other informants. It has been argued that collateral information should be included when making diagnoses of these conditions. However, Zimmerman (Reference Zimmerman1994) concluded that agreement between the two sources of information is generally poor and that the data remain insufficient to recommend one over the other.

Impact on services

Gender and the impact of personality disorder on use of services revealed some important differences from previous studies in clinical populations. The evidence that those with personality disorders, particularly cluster B disorders, consult services much more frequently than others (Reference Bender, Dolan and SkodolBender et al, 2001; Reference Jackson and BurgessJackson & Burgess, 2004) was shown in the unadjusted prevalences in our study, but disappeared after adjusting for demographic and Axis I disorders. Only the higher rate of counselling and psychotropic medication prescription for those with cluster C disorders remained in the adjusted model, suggesting that personality disorder in the absence of comorbid Axis I disorder might not be as important in the use of healthcare services as is often postulated. This may be explained by the current organisation and delivery of mental health services in the UK and by our findings that people with cluster A and B disorders are more likely to present for treatment of their comorbid Axis I disorders than their Axis II disorders. Nevertheless, services for individuals with a primary diagnosis of personality disorder are being introduced in the UK (Home Office & Department of Health, 1999; National Institute for Mental Health in England, 2003).

Future preventive strategies

The high incidence of personality disorder in those who have been in local authority or institutional care, particularly in the cluster B group, and their subsequent criminal convictions, suggest that preventive and treatment strategies in this population could have a major influence on public health. Currently much less attention is given to the involvement of these individuals in treatment programmes (American Psychiatic Association, 2001) and there are arguments for a change in focus here. Furthermore, interventions during childhood and adolescence are increasingly shown to be effective and cost-efficient (Reference Coid, Farrington and CoidCoid, 2003; Reference Welsh, Farrington and CoidWelsh, 2003). The fundamental question is whether services should continue to focus on a small group of symptomatic, help-seeking individuals with type S (treatment-seeking) disorders (Reference Tyrer, Mitchard and MethuenTyrer et al, 2003) or on the larger, currently ‘hidden’ population we have identified with multiple social impairments, those leaving social services and institutional care for children, and those presenting in adulthood to criminal justice instead of healthcare agencies.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Approximately 1 in 20 community residents in Britain have a personality disorder.

-

▪ Certain demographic subgroups have an especially high prevalence of personality disorders.

-

▪ The number of people with cluster B personality disorders who have been in care in childhood and are at greater risk of entering the criminal justice system indicates a need for preventive interventions.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Not all of those selected to participate in the study could be examined.

-

▪ The sample size precluded investigation of rare personality disorders.

-

▪ The survey did not include data obtained from informants or collateral sources.

Acknowledgement

The Office for National Statistics was supported by a grant from the Department of Health.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.