Fatal self-harm is a global problem responsible for around 1 million deaths each year (World Health Organization, 2001; Reference Krug, Dahlberg and MercyKrug et al, 2002). In most countries the highest incidence is in elderly people, in part because self-harm is more often fatal in this age group (Reference Spicer and MillerSpicer & Miller, 2000; Reference Miller, Azrael and HemenwayMiller et al, 2004; Reference Muhlberg, Becher and HeppnerMuhlberg et al, 2005). The high incidence is commonly explained by elderly people using larger amounts of poison or more lethal methods, and being more intent on dying, owing to chronic illness and social isolation (Reference Harwood, Jacoby, Hawton and van HeeringenHarwood & Jacoby, 2000; Reference Conwell, Duberstein and CaineConwell et al, 2002; Reference Krug, Dahlberg and MercyKrug et al, 2002).

One contributor to the age-related pattern of fatal self-harm that is little discussed is the physical vulnerability of elderly people (Reference Conwell, Duberstein and CaineConwell et al, 2002). Elderly people may die more often than young people after self-harm because their bodies may be unable to cope with either the act or its treatment. It has so far been difficult to assess this vulnerability while controlling for severity of the attempt, since data on (for example) the height jumped from or the number of tablets ingested as markers of severity are not readily available.

The most common single poison taken for self-harm in Sri Lanka is yellow oleander (Thevetia peruviana) seeds (Eddleston et al, Reference Eddleston, Ariaratnam and Meyer1999, Reference Eddleston, Gunnell and Karunaratne2005a ). Compared with other poisons, oleander seeds are highly toxic in small quantities. Most patients take between one and seven seeds and on admission find it easy to recall exactly how many they have ingested. Since it is therefore possible to quantify the number of seeds ingested, and thereby control for the severity of the attempt, we have been able to use oleander seed poisoning to look at the effect of age on outcome, independent of the act's severity. We have recruited over 1900 oleander-poisoned patients to a cohort study that has allowed us to address the issue of physical vulnerability in selfharming elderly people.

METHOD

All patients admitted to the adult medical wards of Anuradhapura or Polonnaruwa general hospitals were seen on admission and managed following a standard protocol. The number of seeds ingested, possible confounders, and outcome were recorded prospectively by study doctors. We used the program Stata (release 8.0 for Windows) for analyses. A randomised controlled trial of superactivated charcoal was nested within this cohort until the trial's termination on 16 October 2004, when no effect of charcoal on outcome was noted (Reference Eddleston, Juszczak and BuckleyEddleston et al, 2005b ). Ethics approval was received from Colombo, Sri Lanka, and Oxfordshire, UK, research ethics committees.

RESULTS

Between 31 March 2002 and 22 October 2004, a sample of 1939 patients poisoned with oleander were recruited to the cohort (age range 12-77 years, median 21 years); 1021 (52.7%) of them were male. The number of seeds ingested was reported by 1697 (87.5%) patients and varied from 0.25 to 30 (median 3.0, interquartile range 2-5). Men ingested more seeds than women (median 3.5 v. 3.0) and older people ingested more seeds than younger people (median number of seeds ingested 3.5 by those aged under 25 years v. 4.5 by those aged 45 years and over; Spearman's rank correlation between age and seed number r=0.18, P<0.001).

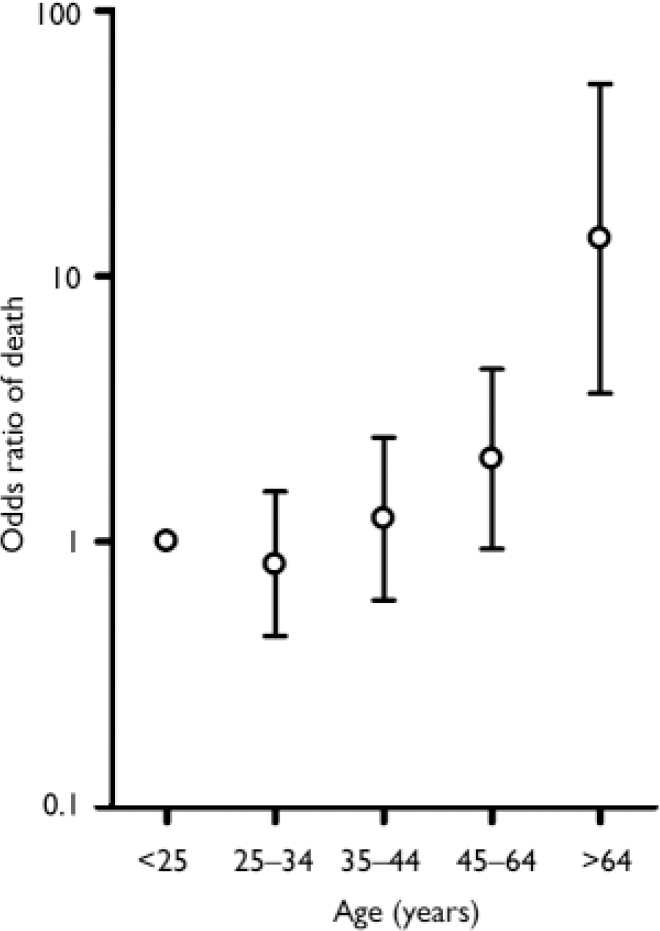

Ninety-four of the 1939 patients (4.8%) died. The female case fatality was lower than the male case fatality (3.9% v. 5.7%; OR=0.68, 95% CI 0.44-1.04). In gender-adjusted logistic regression models restricted to the 1697 cases with data on seed number, the risk of death increased with age (OR=1.40, 95% CI 1.18-1.66, for every 10-year increase in age). Additionally controlling for the number of seeds ingested, the odds ratio of death for every 10-year increase in age was slightly attenuated (OR=1.32, 95% CI 1.10-1.58) in age (Fig. 1). The odds ratio of death for people over the age of 65 years was 13.8 (95% CI 3.6-53.0) compared with people under the age of 25 years.

Fig. 1 Odds ratio of death for patients poisoned by yellow oleander, controlled for number of seeds ingested and grouped by age, relative to those under 25 years old. Bars indicate 95% CI.

In age- and gender-adjusted models, the number of seeds ingested was independently associated with risk of death: OR for every additional seed ingested, 1.21 (95% CI 1.14-1.28). Associations were unaffected in models controlling for whether or not the patient took part in the randomised trial or the treatment received.

DISCUSSION

Although the literature on fatal self-harm in elderly people always discusses their high intent to die (Reference Harwood, Jacoby, Hawton and van HeeringenHarwood & Jacoby, 2000; Reference de Leode Leo, 2001; Reference Krug, Dahlberg and MercyKrug et al, 2002), these people's relative physical vulnerability to the act of self-harm and to its treatment is only rarely mentioned (Reference Conwell, Duberstein and CaineConwell et al, 2002). We have noted many elderly people dying in Sri Lanka from pesticides and oleander seeds who reported ingesting relatively small amounts. However, we are unaware of any previous empirical study of their greater vulnerability to the effects of self-poisoning, controlling for the quantity of poison ingested. Using the example of yellow oleander poisoning, we show in this study that the excess deaths among elderly people, when controlled for the amount of poison ingested and therefore the severity of the act, is due in part to their increased frailty. Some of the vulnerability may result from comorbid illnesses such as ischaemic heart disease, which would make the use of atropine (the conventional treatment for oleander poisoning) more hazardous. Another reason might be that the lower body weight of elderly people and/or their reduced elimination of poisons result in higher concentrations.

There are two main limitations to our analysis. First, inaccuracies in the reported number of seeds ingested will limit our ability to control fully for the effect of severity (as measured by the quantity of oleander seeds consumed), leading to an over-estimate of the effect of age. Nevertheless, seed number was associated with case-fatality, and controlling for seed number in our model only slightly (by 20%) attenuated the associations we observed. Furthermore, unlike self-poisoning with pharmaceuticals - in which tens, if not hundreds, of tablets are often ingested - the number of oleander seeds ingested is far fewer (median 3) and therefore the reported number ingested is likely to be reasonably accurate. Second, it is possible that other factors such as delays in seeking treatment or greater absorption of poison might contribute to their poorer outcome.

This study shows that elderly people are highly susceptible to the effects of poisoning and may die despite taking a relatively small amount of poison. This is likely to be true for all poisons, not just yellow oleander. Suicide prevention efforts in this age group must involve not only improved mental health and social services, and restriction of access to lethal means, but also access to high-quality medical treatment and antidotes to reduce the number of elderly patients who die from self-harm.

Acknowledgements

We thank the provincial director, hospital directors, consultant physicians and medical and nursing staff of the study hospitals for their support, the Ox - Col study doctors for their work, and Robin Jacoby for review. M. E. is a Wellcome Trust Career Development Fellow and is funded by grant 063560 from the Tropical Interest Group. The South Asian Clinical Toxicology Research Collaboration is funded by the Wellcome Trust/National Health and Medical Research Council International Collaborative Research Grant 071669MA.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.