Depression shows a strong association with numerous chronic physical conditions, Reference Prince, Patel, Saxena, Maj, Maselko and Phillips1–Reference Patten, Beck, Kassam, Williams, Barbui and Metz6 including diabetes, arthritis, multiple sclerosis, congestive heart failure, hypertension, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and end-stage renal disease. There are further associations with non-specific syndromes such as obesity, Reference Scott, McGee, Wells and Oakley Browne7 chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. Reference Patten, Beck, Kassam, Williams, Barbui and Metz6 The coexistence of depression and chronic physical conditions predicts significantly worsened health status Reference Moussavi, Chatterji, Verdes, Tandon, Patel and Ustun8 and functional disability. Reference Egede2 Depression is considered by some to be a modifiable risk factor for morbidity and mortality in conditions such as diabetes Reference Ismail, Winkley, Stahl, Chalder and Edmonds9–Reference Von Korff, Katon, Lin, Simon, Ludman and Oliver11 and cardiovascular disease. Reference Taylor12–Reference Frasure-Smith and Lesperance14 In addition, suicide may be relatively more common in those with certain chronic physical illnesses. Reference Allebeck, Bolund and Ringback15,Reference Christensen, Vestergaard, Mortensen, Sidenius and Agerbo16 Individuals with depression are three times less likely to adhere to medical treatment than individuals without depression. Reference DiMatteo, Lepper and Croghan17

Effective treatment of depression might therefore be expected to improve functional disability and health-related quality of life for people with depression and chronic physical health problems. Even if these predicted benefits are discounted, the effective treatment of depression in chronic physical illness can be considered no less desirable than the effective treatment of depression in the absence of physical health problems. In the clinical care of this population, however, depression is often not recognised and diagnosed. When it is recognised, some clinicians may be reluctant to prescribe antidepressants in physical illness because of concerns about adverse physical effects or drug interactions. Our aim was to systematically appraise the effects of treating depression with pharmacological treatment in adults with chronic medical conditions and to calculate their effect size and assess their effect on remission rates and quality of life.

In 2009, the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) produced evidence-based guidelines on the treatment of depression in chronic physical health problems. 18 As part of this process, we conducted a systematic review of the efficacy and safety of antidepressant medication in depression in the context of chronic physical conditions.

Method

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

The full review protocol has been published in the guideline on depression in chronic physical health problems, which was commissioned by NICE. 18 Briefly, a search was conducted for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving the comparison of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), venlafaxine, duloxetine, mirtazapine, mianserin, trazodone (and other named antidepressants licensed since 1958) with placebo or other antidepressants in participants with depression and a chronic physical illness using five electronic bibliographic databases (CENTRAL, CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO).

A priori defined chronic physical health problems included asthma, cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, end-stage renal disease, epilepsy, general medical illness, HIV disease, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, rheumatoid arthritis and stroke. Participants with a range of (sometimes unspecified) chronic physical conditions recruited from general medical wards or receiving home healthcare for chronic conditions were grouped under general medical illness for the purposes of this analysis. Depression was defined as a DSM or ICD diagnosis of depression or identified as scoring positive for depression according to a validated depression scale.

Included outcomes were remission, response, discontinuation for any reason, discontinuation due to adverse events, mean score on a validated depression scale, mean score on quality of life measure and physical health outcomes.

Extensive search terms for depression and RCTs were used with no limitations set for interventions, outcomes, or physical health conditions in order to maximise sensitivity of the search (see the online supplement for details of the search strategy used for MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and PsycINFO). The search was part of a larger search for evidence relevant to the depression and chronic physical health problem guideline. Each database was searched from inception to March 2009. Additional papers were found by searching the references of retrieved articles, tables of contents of relevant journals, previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses of depression and chronic physical health problems, written requests to experts and suggestions made by the members of the Guideline Development Group. The search was repeated in December 2009.

Quality assessment

All studies that met the eligibility criteria above were assessed for methodological quality using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) checklist for RCTs (includes items on method of randomisation, allocation concealment, masking, completion of treatment and differences between groups other than treatment). 19 Studies that were not clearly described as randomised were excluded from the efficacy review. Effectiveness trials were included in the safety review if they included a sample size greater than 200 and had a control group. We created GRADE profiles and classified the overall quality of the evidence (high, moderate, low, very low) using the GRADE system, Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Vist, Kunz, Falck-Ytter and onso-Coello20 which takes into account quality assessment of individual studies (as examined in the SIGN checklist discussed above), the consistency of the results (consistency indicated by I Reference Egede2 less than 50% were downgraded) and the directness (whether or not participants were sufficiently applicable to the target population of the review, see above) of the evidence.

Data extraction

The assessment of study quality and outcome data extraction were completed by one systematic reviewer and double-checked by a second for accuracy, with disagreements resolved by discussion. Where available, data were extracted for the following efficacy outcomes: mean depression scale score (both clinician-rated and patient-rated scales were extracted where available. For studies reporting more than one scale, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) Reference Hamilton21 was extracted in favour of other clinician-rated scales. Similarly, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) Reference Beck and Beamesderfer22 was favoured over other self-report measures); response (e.g. proportion of participants experiencing a 50% improvement in depression score); remission (no longer meeting the cut-off for depression diagnosis on a depression scale); quality of life (e.g. Short Form–36 (SF–36)); 23 and physical health symptoms. With regard to safety and tolerability, the main outcome measure assessed was withdrawals from trials due to adverse effects. We also recorded and compared numbers of participants leaving studies early for any reason.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was used, where appropriate, to synthesise the evidence using Review Manager 5 software for Windows. Reference Cochrane24 Intention-to-treat with last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) was favoured over observed case (although it was recognised that the LOCF may introduce an unknown level of bias). For consistency of presentation, all continuous data were entered into Review Manager in such a way that negative effect sizes represented an effect that favoured the active drug. The standardised mean difference (SMD) or effect size was calculated from continuous data and the risk ratio (RR) was calculated from binary data. Data from more than one study were pooled using a random-effects model. Publication bias was assessed by visually inspecting the symmetry of funnel plots and, formally, using Egger's test. Reference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder25

Results

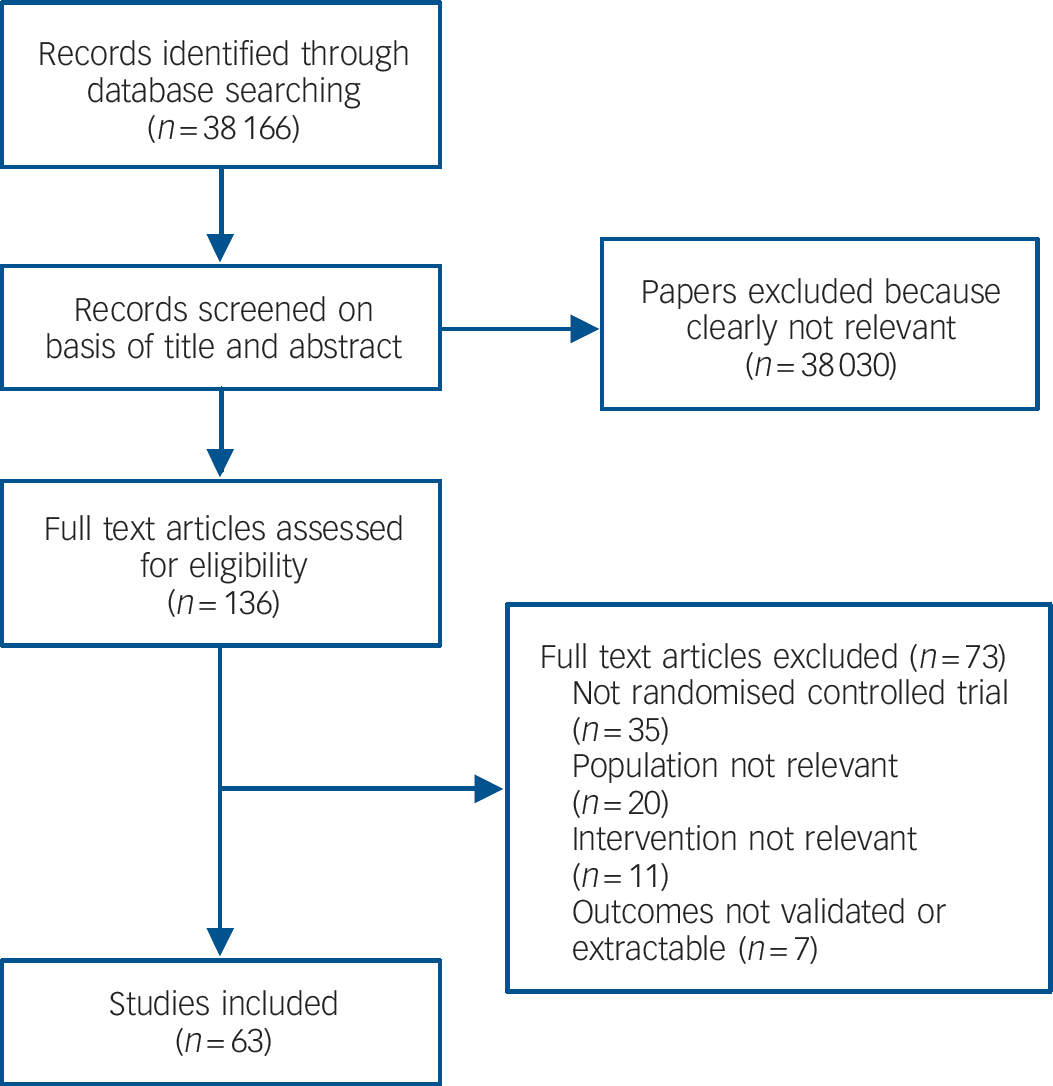

We found 63 studies meeting inclusion criteria (Fig. 1 and online Table DS1). There was no evidence of publication bias as assessed by funnel plots and Egger's test for all comparisons.

SSRIs v. placebo

A total of 35 RCTs compared SSRIs with placebo for people with depression and chronic physical health problems. Reference Musselman, Somerset, Guo, Manatunga, Porter and Penna26–Reference McFarlane, Kamath, Fallen, Malcolm, Cherian and Norman60 (One of these reports Reference Tollefson and Holman42 was treated as three separate trials by abstracting data from an a priori secondary analysis Reference Small, Birkett, Meyers, Koran, Bystritsky and Nemeroff61 that grouped participants according to the number of chronic physical illnesses from which they suffered.) All but three Reference Chen, Wang, Chen, Sheng and Zhu29,Reference Paile-Hyvarinen, Wahlbeck and Eriksson45,Reference Yang, Zhao and Bai53 were double-blind trials. Seven studies examined the treatment of depression in stroke, five in diabetes, four each in cardiovascular disease, cancer, Parkinson's disease and general medical illness, three in HIV, two in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and one in asthma, renal disease and multiple sclerosis.

Fig. 1 Study flow diagram for efficacy studies.

Fig. 2 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) v. placebo: mean change in observer-rated depression rating scale score.

MDD, major depressive disorder; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MS, multiple sclerosis; GM, general medical illness; CVD, cardiovascular disease; Std., standard; IV, inverse variance.

There was consistent evidence that SSRIs had a small-to-medium benefit on depression outcomes in comparison with placebo whether the analysis considered all studies or was confined to double-blind studies only (Fig. 2). The SSRIs were associated with higher levels of remission and response when compared with placebo (Table 1). Remission: (all studies: RR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.73–0.91; double blind only: RR = 0.88, 95% CI 0.81–0.95), response: (all studies: RR = 0.83, 95% CI 0.71–0.97; double blind only: RR = 0.89, 95% CI 0.81–0.98).

Table 1 Evidence summary of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors v. placebo

| Participants (studies), n | Quality of the evidence, GRADE | Effect size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | SMD | RR | 95% CI | ||

| Depression | |||||

| Continuous measures | |||||

| Patient rated | 923 (12) | Moderatea | – 0.19 | – 0.36 to –0.02 | |

| Observer rated | 2133 (26) | Lowa,c | – 0.34 | – 0.47 to –0.20 | |

| Not achieving success/remission | |||||

| Observer rated | 1197 (14) | Moderatea | 0.81 | 0.73 to 0.91 | |

| Patient rated | 60 (1) | Moderated | 0.74 | 0.46 to 1.18 | |

| Non-response | |||||

| Patient rated | 279 (3) | Lowb,c | 0.73 | 0.44 to 1.22 | |

| Observer rated | 1267 (19) | Lowa,c | 0.83 | 0.71 to 0.97 | |

| QoL: continuous measures, e.g. SQOLI, FACT–G | 524 (7) | Moderatea | – 0.27 | – 0.44 to –0.1 | |

| Physical outcome/QoL – General physical functioning/well-being (SF–36 physical component) | 338 (5) | Moderateb | 0.02 | – 0.19 to 0.23 | |

| Leaving the study early | |||||

| Any reason | 3137 (25) | Moderatea | 1.13 | 0.97 to 1.32 | |

| As a result of adverse events | 1661 (13) | Moderatea | 1.80 | 1.16 to 2.78 | |

A robust positive effect was also found for mean change in depression rating scale score (effect size), although there were differences in the size of the effect depending on whether patient-rated or observer-rated scales were used. Patient-rated scales (all studies: SMD = –0.19, 95% CI –0.36 to –0.02; double blind only: SMD = –0.20, 95% CI –0.38 to – 0.02). Observer-rated scales (all studies: SMD = –0.34, 95% CI – 0.48 to –0.20; double blind only: SMD = –0.28, 95% CI – 0.39 to –0.17) (Table 1 andFig. 2).

There were mixed data concerning tolerability of SSRIs. No differences were found compared with placebo for leaving the study for any reason (RR = 1.13, 95% CI 0.97–1.32). However, participants receiving SSRIs were more likely to leave the study early because of adverse events (RR = 1.80, 95% CI 1.16–2.78).

There were fewer data on health-related quality of life and physical health outcomes. Where these were reported, measures differed substantially between studies. In total there were seven studies that provided data on quality of life, indicating a small benefit in favour of SSRIs (SMD = –0.27, 95% CI – 0.44 to –0.10). There were five studies reporting the physical subscale of the SF–36 23 that showed no difference between groups (SMD = 0.02, 95% CI –0.19 to 0.23).

It was not possible or appropriate to pool data on physical health outcomes because of differences between physical health conditions in which outcomes were examined, but also because of varied reporting of outcomes.

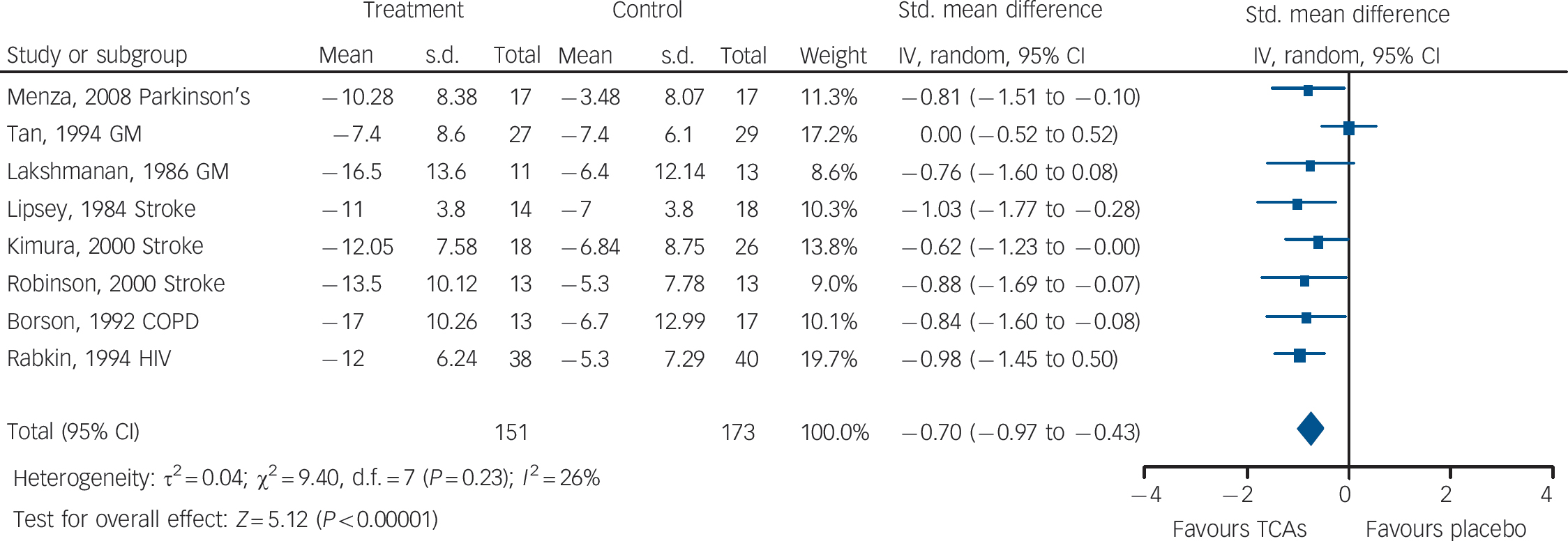

Fig. 3 Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) v. placebo: mean change in observer-rated depression rating scale score.

GM, general medical illness; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Std., standard; IV, inverse variance.

TCAs v. placebo

We found nine double-blind RCTs that compared TCAs with placebo, Reference Robinson, Schultz, Castillo, Kopel, Kosier and Newman30,Reference Andersen, Aabro, Gulmann, Hjelmsted and Pedersen62–Reference Tan, Barlow, Abel, Reddy, Palmer and Fletcher69 mostly conducted in the 1980s and 1990s. Three of these studies examined the effect of TCAs in depression occurring in the context of stroke, two in general medical illness and one each in Parkinson's disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes and HIV.

There was evidence of medium-to-large benefits on most depression outcomes (Table 2 andFig. 3). Participants receiving TCAs were more likely to respond to treatment (RR = 0.55, 95% CI 0.43–0.70). There was no statistically significant effect on remission (RR = 0.70, 95% CI 0.40–1.25) (two studies reported this outcome). Mean differences on observer-rated depression scales were of a medium-to-large magnitude (SMD = –0.70, 95% CI –0.97 to –0.43) (Fig. 3). Similar effects were found on patient-rated scales (SMD = –0.58, 95% CI –1.14 to – 0.02).

Table 2 Evidence summary of tricyclic antidepressants v. placebo

| Participants (studies), n | Quality of the evidence, GRADE | Effect size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMD | RR | 95% CI | |||

| Depression | |||||

| Continuous measures: observer rated | 324 (8) | Moderatea | – 0.70 | – 0.97 to –0.43 | |

| Non-response (<50% improvement): observer rated | 224 (5) | Moderatea | 0.55 | 0.43 to 0.70 | |

| Not achieving success/remission (reaching a specified cut- off): patient rated | 75 (2) | Lowb,c | 0.70 | 0.40 to 1.25 | |

| Leaving the study early | |||||

| Any reason | 302 (6) | Moderateb | 1.23 | 0.81 to 1.88 | |

| As a result of adverse events | 239 (5) | Moderateb | 1.88 | 0.99 to 3.57 | |

There was evidence of a trend for TCAs being less well tolerated compared with placebo (Table 2). People on TCAs were not significantly more likely to leave the study for any reason (6 studies, 302 participants) (RR = 1.23, 95% CI 0.81–1.88), but were numerically more likely to leave because of adverse events (5 studies, 239 participants) (RR = 1.88, 95% CI 0.99–3.57).

There were very limited data on quality of life and physical health outcomes and so a meta-analysis of these outcomes was not undertaken.

Other drugs v. placebo

There was one study of trazodone Reference Raffaele, Rampello, Vecchio, Tornali and Malaguarnera70 in post-stroke depression that indicated large benefits in comparison with placebo for mean depression rating scale score (SMD = –1.03, 95% CI – 1.93 to –0.13). This study was not double blind. There was one double-blind study of mirtazapine in depression after myocardial infarction. Reference van den Brink, van Melle, Honig, Schene, Crijns and Lambert71 Participants in the mirtazapine group were less likely to leave the study for any reason compared with placebo (RR = 0.57, 95% CI 0.35–0.94). There were small suggested benefits in favour of mirtazapine in terms of remission (0.87, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.21), response (0.83, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.20) and effect size (SMD = –0.21, 95% CI –0.62 to 0.20), but none of these effects was statistically significant. Wise and colleagues Reference Wise, Wiltse, Iosifescu, Sheridan, Xu and Raskin72 conducted a double-blind trial on duloxetine in elderly individuals with medical comorbidities that was found to be associated with a small-to-medium benefit in terms of mean difference on depression scale score (patient-rated: SMD = –0.37, 95% CI –0.67 to –0.14; observer-rated: SMD = – 0.43, 95% CI –0.71 to –0.16).

Two studies examined mianserin v. placebo Reference Costa, Mogos and Toma73,Reference van Heeringen and Zivkov74 (both double blind), which suggested strong benefits favouring mianserin on leaving the study for any reason (RR = 0.43, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.75), response (RR = –0.47, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.74) and mean difference for depression score as measured on the HRSD (mean difference –5.97, 95% CI –9.14 to –2.80, SMD = –0.64, 95% CI –1.00 to –0.29). We included one trial of psychostimulants for people with HIV Reference Wagner and Rabkin75 that lasted 2 weeks. There was a small non-significant effect on depression (SMD = – 0.36, 95% CI –1.20 to 0.49), but a large effect on fatigue (SMD = – 1.64, 95% CI –2.64 to –0.65).

SSRIs v. TCAs

We found 14 studies comparing TCAs and SSRIs. Reference Musselman, Somerset, Guo, Manatunga, Porter and Penna26,Reference Chen, Wang, Chen, Sheng and Zhu29,Reference Robinson, Schultz, Castillo, Kopel, Kosier and Newman30,Reference Menza, Fronzo Dobkin, Marin, Mark, Gara and Buyske38,Reference Devos, Dujardin, Poirot, Moreau, Cottencin and Thomas50,Reference Li and Ma76–Reference Pollock, Laghrissi-Thode and Wagner84 Four of these studies were not double blind. Reference Chen, Wang, Chen, Sheng and Zhu29,Reference Li and Ma76,Reference Huang82,Reference Antonini, Tesei, Zecchinelli, Barone, De and Canesi83 Three of the studies examined the effect of antidepressants in depression in the context of Parkinson's disease, three in cancer and one each in epilepsy, HIV, stroke, cardiovascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis and ‘vascular depression’.Table 3 and Figs4 and5 summarise the main outcomes of the analysis comparing SSRIs and TCAs.

Table 3 Evidence summary of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors v. tricyclic antidepressants

| Participants (studies), n | Quality of the evidence, GRADE | Effect size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | SMD | RR | 95% CI | ||

| Depression | |||||

| Continuous measures: observer rated | 471 (9) | Moderatea,b | 0.14 | – 0.12 to 0.41 | |

| Remission (below cut-off): observer rated | 170 (5) | Moderatea | 1.11 | 0.83 to 1.48 | |

| Non-response (<50% reduction): observer rated | 625 (8) | Moderatea | 1.00 | 0.83 to 1.21 | |

| Leaving the study early | |||||

| Any reason | 699 (10) | Moderatea | 0.80 | 0.56 to 1.14 | |

| As a result of adverse events | 441 (8) | Moderatea | 0.90 | 0.54 to 1.51 | |

Efficacy did not differ between the two groups of drugs (Fig. 5), with no statistically significant or clinically relevant differences observed on remission response or effect size (Table 3, top three rows)

There was a trend for SSRIs to be associated with better tolerability (Fig. 4). For example, people who received SSRIs were numerically less likely to leave the study early for any reason (Fig. 3) and numerically less likely to leave the study due to adverse events, but neither of these findings were statistically significant (Table 3, bottom two rows).

Other head-to-head comparisons

We found four head-to-head trials of comparisons other than SSRIs compared with TCAs. All but one Reference Zhao, Puurunen, Sivenius, Jolkkonen and Schallert85 were double-blind trials. All trials indicated little if any benefit of one drug or drug class over another. The trials covered a range of medical conditions including diabetes, Reference Gulseren, Gulseren, Hekimsoy and Mete86 epilepsy, Reference Robertson and Trimble87 stroke Reference Zhao, Puurunen, Sivenius, Jolkkonen and Schallert85 and general medical illness, Reference Schifano, Garbin, Renesto, De Dominicis, Trinciarelli and Silvestri88 and included participants with both mild and moderate depression. One study comparing two different SSRIs Reference Gulseren, Gulseren, Hekimsoy and Mete86 (n = 23) did not indicate any benefit for either drug (fluoxetine and paroxetine) in terms of efficacy and tolerability, with no statistically significant differences observed on leaving the study early (RR = 0.46, 95% CI 0.05 to 4.38), remission (RR = 0.76, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.80), response (RR = 1.15, 95% CI 0.41 to 3.21) or effect size (SMD = 0.00, 95% CI –0.88 to 0.88). Another comparing citalopram and venlafaxine Reference Zhao, Puurunen, Sivenius, Jolkkonen and Schallert85 (n = 82) did not indicate any benefit for either drug. The outcomes for leaving the study early (RR = 0.69, 95% CI 0.31–1.55), remission (RR = 0.90, 95% CI 0.71–1.13) and response (RR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.50–1.13) were not statistically significantly different. Based on one small study Reference Robertson and Trimble87 (n = 42), there was no benefit in terms of efficacy for TCAs when compared with nomifensine, with response data indicating no statistically significant differences (RR = 3.50, 95% CI 0.89–13.78). One further study Reference Schifano, Garbin, Renesto, De Dominicis, Trinciarelli and Silvestri88 (n = 48) compared maprotiline and mianserin but found no statistically significantly differences between the two. For example, results for leaving the study early (RR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.51), response (RR = 0.75 (95% CI 0.47 to 1.19) and effect size (SMD = –0.47, 95% CI –1.15 to 0.21) did not indicate that one drug was more efficacious than the other.

Safety studies

There were three studies that met the eligibility criteria of the review on the safety of antidepressants in chronic physical health problems. Each addressed the use of antidepressants after myocardial infarction.

Fig. 4 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) v. tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): leaving the study for any reason.

CVD, cardiovascular disease.

Fig. 5 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) v. tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): mean change in observer-rated depression rating scale score.

CVD, cardiovascular disease; Std., standard; IV, inverse variance.

MIND–IT (Myocardial Infarction and Depression – Intervention Trial)

This study focused on the safety of antidepressants in people who had a myocardial infarction and within this study a nested RCT was conducted comparing mirtazapine and placebo (which is included in the meta-analysis described earlier). Reference van den Brink, van Melle, Honig, Schene, Crijns and Lambert71 Details are given inTable 4. It was observed Reference van Melle, de Jonge, Honig, Schene, Kuyper and Crijns89 that antidepressant use did not affect remission or cardiac event rate. In a follow-up subanalysis, response to mirtazapine seemed to predict lower risk of cardiac events (7.4% over 18 months) than both absence of pharmacological treatment (control group; event rate 11.2%) and failure of pharmacological treatment (event rate 25.6%). Reference de Jonge, Honig, van Melle, Schene, Kuyper and Tulner90

Table 4 Safety studies of antidepressants after myocardial infarction

| Study | Design | Intervention (n) | Control (n) | Participants (n) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIND–IT Reference van Melle, de Jonge, Honig, Schene, Kuyper and Crijns89 | Double-blind comparison of antidepressant v. care as usual | Mirtazapine (47) followed by citalopram (15) if no response or placebo (44) followed by citalopram (23) if no response (n = 91, in total) | Usual care (122) (20 received antidepressants) | Participants with depression after MI (n = 213) | Non-remission: 30.5% intervention, 32.1% control (OR = 0.93, 95% CI 0.53–1.63) |

| Cardiac events: 14% intervention, 13% control | |||||

| Use of antidepressant not associated with altered rate of cardiac events (OR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.38–1.84) | |||||

| ENRICHD Reference Berkman, Blumenthal, Burg, Carney, Catellier and Cowan91 | Secondary comparison of outcomes in participants receiving antidepressants | Antidepressant use (initially sertraline) (n = 446) | No antidepressant use (n = 1388) | Participants with depression after MI (n = 1834) | All cause mortality: adjusted mortality 0.63 (95% CI 0.43–0.93) |

| Recurrent MI: adjusted mortality 0.57 (95% CI 0.38–0.87) | |||||

| Use of antidepressants reduced mortality and recurrence of MI | |||||

| SADHART Reference Glassman, O'Connor, Califf, Swedberg, Schwartz and Bigger36 | Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled comparison of sertraline and placebo | Sertraline 50–200 mg day for 24 weeks (n = 186) | Placebo for 24 weeks (n = 183) | Participants with depression post-MI (74%) or unstable angina (26%) (n = 369) | Response rates: 67% sertraline, 53% placebo (P = 0.01) |

| Severe cardiovascular adverse events: 14.5% sertraline, 22.4% placebo (NS) | |||||

| Sertraline no different from placebo on measures of left ventricular ejection fraction, QTc prolongation and other measures of cardiovascular function or mortality |

ENRICHD (Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease)

This US study looked at people who had experienced a myocardial infarction. It mainly consisted of participants who had a relatively recent myocardial infarction (median 6 days), as compared with a minimum period of 3 months post-myocardial infarction for MIND-IT. In a paper concerned with outcomes relating to antidepressant use, Reference Berkman, Blumenthal, Burg, Carney, Catellier and Cowan91 it was reported that there was high usage of antidepressants (mainly SSRIs) in both treatment (baseline 9.1%, 6 months 20.5%, end of follow-up 28%) and usual care (baseline 3.8%, 6 months 9.4%, end of follow-up 20.6%) groups (Table 4). For the primary outcome of the study, death or non-fatal myocardial infarction, there was a reduced risk for those taking antidepressants, particularly SSRIs. Reference Taylor, Youngblood, Catellier, Veith, Carney and Burg92

SADHART (Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial)

This trial Reference Glassman, O'Connor, Califf, Swedberg, Schwartz and Bigger36 included 369 patients with an acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina and comorbid major depressive disorder. (The data on the efficacy of sertraline for depression symptoms were included in the meta-analysis described earlier.) Sertraline appeared neither to increase nor decrease cardiovascular risks or mortality but was more effective than placebo in treating depression (Table 4).

Discussion

Main findings

In this systematic review we have examined the key outcomes of 63 randomised controlled trials (5794 participants) of antidepressants in a range of chronic physical conditions. Antidepressants of all types appear to be effective in depression in the context of chronic physical conditions but no particular drug or group of drugs was shown to have clear superiority in respect to efficacy or tolerability. Antidepressants of all groups were less well tolerated than placebo (although with TCAs this did not reach statistical significance). Only SSRIs were observed to improve quality of life measures; data were insufficient to draw conclusions about other antidepressants.

The effect size calculated here for antidepressants in depression occurring in the context of physical illness is broadly similar to that seen in depression not associated with physical illness: usually between 0.2 and 0.6. Reference Turner, Matthews, Linardatos, Tell and Rosenthal93 For SSRIs in physical illness, the effect size was shown to be around 0.3 (depending on the subanalysis conducted) and around 0.6 for TCAs. No inferences should be drawn from the numerical differences in effect size noted for different drugs because in all cases confidence intervals overlapped and moreover, each effect size was calculated from markedly different studies in different populations. Participants receiving either SSRIs or TCAs were more likely (around twice as likely) to leave studies early because of adverse effects. Notably, confidence intervals for TCAs did not exclude the possibility of their being no different from placebo, although with fewer studies involving TCAs, this may at least partly be a result of relatively lower statistical power compared with SSRIs. Data on other drugs were insufficient to draw conclusions in this regard.

Our results are similar to those of a recent Cochrane review of antidepressants in physically ill people. Reference Rayner, Price, Evans, Valsraj, Higginson and Hotopf94 Using somewhat different search criteria, this review included 44 placebo-controlled studies involving 3372 participants (25 studies and 1674 participants in the efficacy analysis). Antidepressants, as a group, were found to be more efficacious than placebo (response: odds ratio (OR) = 2.33, 95% CI 1.80–3.00). The SSRIs, but not the TCAs, were associated with a statistically significant increased risk of withdrawal from trials (at 6–8 weeks, for SSRIs OR = 1.43, 95% CI 1.04–1.96; TCAs OR = 1.69, 95% CI 0.98–2.92).

Overall, no particular drug can be recommended in any particular physical condition based on data reviewed here or in the above mentioned Cochrane review. Reference Rayner, Price, Evans, Valsraj, Higginson and Hotopf94 Nonetheless, SSRIs may be seen as drugs of choice in people with chronic physical health problems assuming interactions and contraindications do not preclude their use. Choice of SSRI may be influenced by findings of a matrix meta-analysis in people without physical health problems that suggested that sertraline and escitalopram had advantages in respect to efficacy and acceptability, Reference Cipriani, Furukawa, Salanti, Geddes, Higgins and Churchill95 with sertraline recommended as a first-choice drug.

Sertraline, mirtazapine and possibly other SSRIs (such as citalopram) appear to be safe post-myocardial infarction (when considering safety outcomes from effectiveness studies included). The advantages of effectiveness studies are, first, that sample sizes tend to be larger and provide longer follow-up than efficacy studies in this area. Second, effectiveness trials seek to minimise differences between study conditions and routine clinical practice and so such findings are more readily applicable to clinical practice. Therefore it is important to compare the results found in these trials with the efficacy trials reviewed above to assess whether they confirm conclusions of the efficacy studies and/or provide additional data not usually reported in other trials. However, it should also be noted there are clear disadvantages in that given the complexity and the reduced level of control usually associated with these studies, it is often difficult to draw firm conclusions on causality. What is clear from these effectiveness studies is that mirtazapine, sertraline and citalopram have, at worst, no deleterious effect on cardiac outcome following myocardial infarction. This is a finding in accord with other safety studies. Reference Strik, Honig, Lousberg, Lousberg, Cheriex and Tuynman-Qua34,Reference Rigotti, Thorndike, Regan, McKool, Pasternak and Chang96 What is less clear is the effect of antidepressants on depression post-myocardial infarction. By no means all studies show a clear advantage for antidepressants over placebo or control in depression post-myocardial infarction (for example, MIND–IT Reference van den Brink, van Melle, Honig, Schene, Crijns and Lambert71 found no advantage for antidepressants over control – this is usually explained by the ephemeral nature of depression after myocardial infarction). However, the possibility that antidepressants might improve mortality post-myocardial infarction and that this may be related to their efficacy in depression should encourage their use. Depression post-myocardial infarction increases mortality by up to sixfold, Reference Frasure-Smith, Lesperance and Talajic13,Reference Frasure-Smith, Lesperance, Juneau, Talajic and Bourassa97,Reference Frasure-Smith, Lesperance and Talajic98 so any positive effects of treatment on mortality are to be welcomed.

Strengths and limitations

There are three important limitations to the present analysis. First, study quality tended to be rated as low or moderate, largely because authors often failed to describe methods of randomisation or efficacy of masking. An important number of studies were not double blind in design. Most studies included only small numbers of participants (usually around 20–60, although there were a handful of much larger studies). Second, the method of analysis – the grouping of drugs by drug class – is open to censure. We could have analysed by individual physical condition and examined the effect of (perhaps all) antidepressants in, say, depression occurring in the context of epilepsy or multiple sclerosis. However, there was a considerable disparity in the number of studies conducted and number of participants included in different physical conditions and so statistical power is likely to have varied considerably. We might then have concluded that antidepressants were effective in treating depression occurring in the context of certain physical conditions but not others. Apparent lack of effect may have then been a result of low statistical power rather than the absence of efficacy. Third, we were unable to determine outcomes for quality of life and physical outcomes for most drug groups. Of 36 studies comparing SSRIs with placebo, 7 included quality-of-life measures and for SSRIs a clear advantage was shown over placebo. For other drugs, too few individual studies included these outcomes for us to make a clear evaluation of their effects.

Advantages of our method include a rigorous and clearly described search technique and quality assessment that uncovered a large number of studies published. Combining study outcomes by meta-analysis allowed us to see clear benefits for drugs or drug groups for which the findings of most individual trials were equivocal. For example, only 6 of 25 trials comparing SSRIs with placebo clearly favoured the SSRI being studied (that is, showed statistically significant advantages). Our meta-analysis of these studies showed a clear efficacy advantage for SSRIs on a range of outcomes.

Clinical implications

Antidepressants appear to be effective but relatively poorly tolerated in the treatment of depression occurring in the context of chronic physical illness. No particular drug or drug group is preferred, although SSRIs may be better tolerated than TCAs and have a clear benefit on quality of life. The SSRIs may also be less likely than TCAs to be involved in pharmacodynamic interactions because they largely lack sedative, antimuscarinic and arrhythmogenic properties. The use of SSRIs (such as sertraline and citalopram) and mirtazapine is safe post-myocardial infarction and may confer benefits on cardiac mortality. Despite clinical concerns over adverse effects and drug interactions, antidepressants should not be withheld in the treatment of depression associated with chronic physical illness.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.