Cannabis use in adolescence has been linked to suboptimal adjustment in young adulthood, typically for those who begin or progress to heavy use. Reference Hall, Degenhardt and Lynskey1,Reference Moore, Zammit, Lingford-Hughes, Barnes, Jones and Burke2 Although common in many countries, Reference Hall and Degenhardt3 most adolescents use cannabis infrequently and it remains unclear whether they are also at risk of negative outcomes. Little prospective research has examined the later life circumstances of adolescent cannabis users who do not progress to heavier use. In one small study of children (n = 85) raised in California during the 1970s, children who experimented with cannabis were reportedly better adjusted psychologically than those who abstained until 18 years. Reference Shedler and Block4 This finding was not replicated in a more recent Californian study which reported that adolescent abstainers had better peer, family and school engagement and less ‘deviant behaviour’ at 23 years than experimenters. Reference Tucker, Ellickson, Collins and Klein5 In this paper we report data from a 10-year population-based cohort study, focusing on: (a) associations between occasional cannabis use during adolescence and psychosocial and drug use outcomes in young adulthood (20–24 years); and (b) modification of these associations according to the trajectory of cannabis use between adolescence and age 20 years, and according to other potential risk factors. We focused in particular on the effect of adjustment for cigarette smoking in adolescence, because of its strong association with cannabis use.

Method

Sample

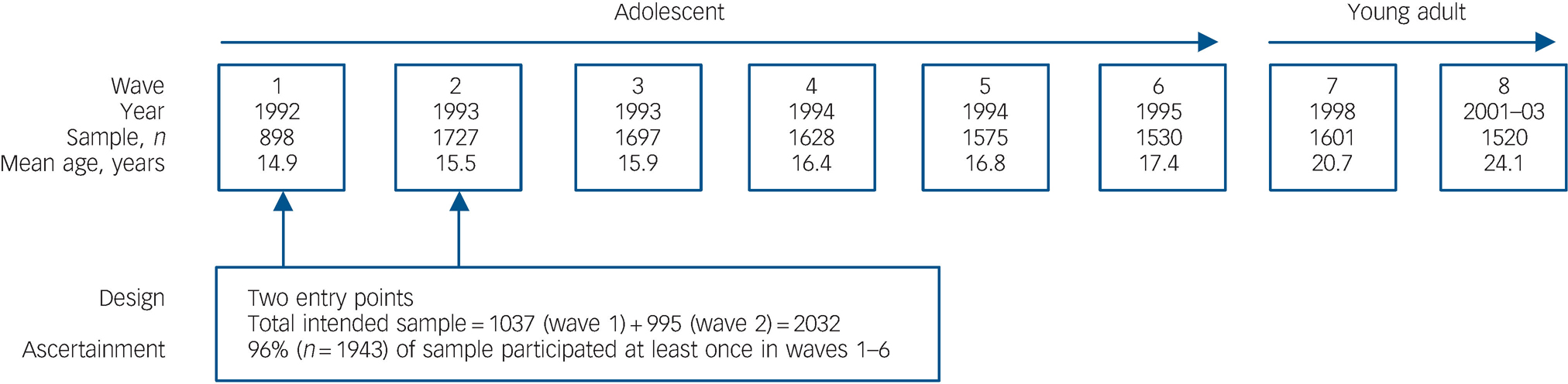

We conducted an eight-wave cohort study, 1992–2003, examining health among young people in Victoria, Australia. Data collection was approved by The Royal Children's Hospital's Ethics in Human Research Committee. The cohort was a representative sample of Victorian mid-secondary school adolescents in 1992, defined in a two-stage cluster sample, with two classes selected at random from a state-wide sample of 44 schools, one class entering the study in year nine, at 13–14 years of age (wave 1) and the second 6 months later (wave 2). Participants were interviewed at four 6-month intervals during the teens (waves 3–6) with two follow-ups in young adulthood: 20–21 years (wave 7) and 24–25 years (wave 8). In waves 1–6, participants self-administered the questionnaire on laptop computers with telephone follow-up of those absent from school. Waves 7 and 8 were undertaken using computer-assisted telephone interviews. Reference Paperny, Aono, Lehman, Hammar and Risser6

From a total sample of 2032 students, 1943 (96%) participated at least once during the adolescent phase (Fig. 1). In wave 8 (April 2001 to April 2003), 1520 were interviewed. Reasons for non-completion at wave 8 were refusal (n = 269), loss of contact (n = 150) and death (n = 4). In this sample, participation from waves 1 to 6 was: 6 waves, n = 543; 5 waves, n = 617; 4 waves, n = 192; 3 waves, n = 56; 2 waves, n = 43; 1 wave, n = 69.

Fig. 1 Sampling and ascertainment in the Victorian Adolescent Health Cohort, 1992–2003.

Measures

Background measures

These included school location, place of birth, parental education and employment status.

Adolescent cannabis use (waves 1–6)

Past 6-month use was categorised as ‘none’, ‘less than weekly’ (occasional) and ‘weekly–daily’ (weekly+). Individuals were classified according to maximum frequency in waves 1–6 (maximum adolescent use). Frequency of use was assessed without specifying method or dose.

Other adolescent measures

Tobacco smoking was recorded using a 7-day retrospective diary and maximum smoking frequency (waves 1–6). Occasional smoking included any smoking within the past month; daily smoking including smoking 6–7 days of the past week.

Long-term high alcohol risk was assessed using a retrospective 1-week diary which provided estimates of alcohol consumed. Participants drinking more than 280 g in the previous week were classified as risky drinkers, according to 2007 draft Australian guidelines. 7

Symptoms of depression and anxiety were assessed at each wave using the computerised revised Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R). Participants with scores >11 Reference Coffey, Carlin, Lynskey, Li and Patton8–Reference Harrington, Fudge, Rutter, Pickles and Hill11 in any wave were classified as symptomatic.

Young adulthood cannabis use (waves 7 and 8)

Maximum past-year cannabis use was categorised into: <5 times (none); >5 times but less than weekly (occasional); and weekly or more (weekly+).

Other outcomes at 24 years (wave 8)

Post-school qualifications and current receipt of government benefits were identified in the final wave. Symptoms of depression and anxiety were assessed with the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ–12), Reference Goldberg12 and were dichotomised at a score >2, a threshold believed to delineate a mixed depression–anxiety state at a lower level than syndromes of major depression and anxiety disorder but where clinical intervention would be appropriate. Reference Lewis and Williams9,Reference Lewis, Pelosi, Araya and Dunn10

Those who had smoked cigarettes within the past month were also identified in wave 8. Nicotine dependence was measured using the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) and was defined as a score of 4 or more, corresponding to a cut-point of 7 or more on the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Reference Fagerstrom, Heatherton and Kozlowski13 Alcohol dependence (DSM–IV) in the past year was assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview 2.1 (CIDI). 14 DSM–IV cannabis dependence among past-year weekly+ users was also assessed using the CIDI. Other illicit drug use included amfetamine, ecstasy and cocaine.

Analysis

We graphed the gender-adjusted prevalence of young adult outcomes according to adolescent cannabis use, stratified by cannabis use frequency at 20 years. Gender-adjusted proportions were obtained using predicted values from logistic regression models. Associations between categories of adolescent cannabis use and outcomes at 24 years were assessed using odds ratios. Wald tests and confidence intervals (CI) were used to assess statistical significance and precision.

Around 22% of the original Victorian Adolescent Health Cohort Survey participants were not interviewed for wave 8 data, and a minority provided data at all waves. Consequently, the results of ‘complete-case’ analyses based on only those with complete data at all waves could potentially be biased. Analyses were therefore performed using the method of multiple imputation Reference Schafer15 to allow for missing data on outcomes and predictor variables. This method has advantages over simpler imputation methods such as mean substitution and last observation carried forward, both in its potential to reduce bias and in the appropriate accounting for variance due to uncertainty about the true unobserved values.

Under the multiple imputation method, several copies of the data-set are created using a modelling process that imputes a value for each missing item, and final analyses are obtained by combining the results obtained by applying standard complete-data methods to each of the imputed data-sets. Imputed values are randomly drawn using a modelling process that allows for uncertainty in the model parameters, and includes predictive information from related variables that may or may not have missing values themselves. In this study, a multivariate normal model was used to impute the missing data to create five different complete data-sets used for the analyses of this paper.

Variables measuring alcohol and drug use, and variables known to be associated with alcohol and drug use, from all eight waves were included in the imputation model, along with key sociodemographic covariates (gender, age, rural/urban residence and parental education). This was done with the stand-alone software package NORM for Windows, applying adaptive rounding post-imputation for binary measures. Reference Bernaards, Belin and Schafer16

Data analysis used Stata 10.0 for Windows with multiple imputation analysis performed using special-purpose Stata commands. Reference Carlin, Galati and Royston17 Parameters were estimated by averaging across the imputed data-sets with Wald-type confidence intervals obtained under multiple imputation using Rubin's combination rules. Reference Schafer15

Results

A third of the cohort (34%; 95% CI 32–37) had used cannabis in the past 6 months in at least one adolescent wave: 331 users (64%, 95% CI 59–68) reported only occasional use and 190 (36%, 95% CI 32–41) reported weekly+ use. In the first adult wave (20 years, wave 7), 60% reported using cannabis, of whom 77% (n = 702) used occasionally and 23% (n = 208) used weekly+. At 24 years (wave 8), 33% (n = 508) used cannabis, of whom 63% (n = 318) reported occasional use and 37% (n = 190) reported weekly+ use.

Association between adolescent cannabis use, background factors and adolescent measures

Adolescent cannabis use was less common in females and in participants born outside Australia (Table 1). Weekly+ users were less likely to have parents with low education, and were more likely to have attended a metropolitan school, than non-users. Depression/anxiety symptoms, alcohol use and cigarette smoking were more likely among both occasional and weekly+ cannabis users compared with non-users.

Table 1 Association of adolescent cannabis use with background factors and other adolescent measures in 1520 cohort participants

| Maximum adolescent cannabis use (waves 1-6) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (n = 999) | Occasional use (n = 331) | Weekly+ use (n = 190) | ||||

| Measure | n a | n (%)b | n (%) | ORc (95% CI) | n (%) | ORc (95% CI) |

| Background factors | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 824 | 582 (71) | 162 (20) | 1 | 80 (10) | 1 |

| Male | 696 | 417 (60) | 169 (24) | 1.5 (1.1-1.9) | 110 (16) | 1.9 (1.4-2.7) |

| Australian birth | ||||||

| Yes | 1339 | 857 (64) | 303 (23) | 1 | 180 (13) | 1 |

| No | 181 | 143 (79) | 28 (15) | 0.55 (0.35-0.89) | 10 (6) | 0.35 (0.17-0.69) |

| Parental education | ||||||

| Parent completed high school | 1035 | 674 (65) | 225 (22) | 1 | 136 (13) | 1 |

| Low parental education | 485 | 325 (67) | 106 (22) | 0.98 (0.74-1.3) | 54 (11) | 0.82 (0.57-1.18) |

| School | ||||||

| Rural | 398 | 263 (66) | 90 (33) | 1 | 45 (11) | 1 |

| Melbourne metropolitan | 1122 | 736 (66) | 241 (21) | 0.96 (0.69-1.3) | 145 (13) | 1.2 (0.80-1.7) |

| Adolescent measures (waves 1-6) | ||||||

| Depression/anxiety symptoms | ||||||

| No | 789 | 570 (72) | 153 (19) | 1 | 67 (8) | 1 |

| Yes | 731 | 430 (59) | 178 (24) | 1.5 (1.2-2.1) | 123 (17) | 2.4 (1.7-3.5) |

| High-risk alcohol use | ||||||

| No | 1373 | 960 (70) | 288 (21) | 1 | 125 (9) | 1 |

| Yes | 147 | 40 (27) | 42 (29) | 3.6 (1.9-6.8) | 65 (44) | 13 (7.5-22) |

| Cigarette smoking | ||||||

| No | 805 | 709 (88) | 81 (10) | 1 (1) | 16 (2) | 1 |

| Yes | 715 | 290 (41) | 250 (35) | 7.5 (5.6-10) | 174 (24) | 27 (15-49) |

Adolescent cigarette smoking was strongly associated with cannabis use. Eight in ten (81%) adolescent cannabis users also reported cigarette smoking, and 59% of smokers reported cannabis use. There was no evidence of effect modification by gender (each interaction Wald chi-squared P>0.1).

Young adult outcomes according to level and trajectory of adolescent cannabis use at 20 years

We classified individuals according to their cannabis use trajectory between the adolescent phase and 20 years: 42% of non-users in adolescence had initiated cannabis use by 20 years, typically occasional use (90%). Of the 331 adolescent occasional users, 28 (8%) abstained at 20 years, 236 (71%) persisted with that level of use, and 67 (20%) escalated to weekly+ use.

Figure 2 displays prevalence estimates of outcomes at age 24 years according to adolescent-onset cannabis use, and frequency of cannabis use at age 20 years, adjusted for gender. For the psychosocial outcomes (post-school qualifications, receipt of welfare, and depression/anxiety), persistent weekly users (those using weekly in adolescence and adulthood) had worse outcomes compared with those who never used, but there was considerable overlap in the confidence intervals around estimates for other categories of users. There was possibly a trend to greater risk of not having post-school qualifications with increasing adolescent cannabis use, which we explore in more detail below.

Fig. 2 Gender-adjusted prevalence of each outcome at age 24 years according to level of cannabis use during adolescence, and then by level of cannabis use at age 20 years. The diameter of the circle reflects the precision of the estimate (essentially the size of the subgroup); the vertical lines represent the 95% confidence interval around the estimate.

a. Cell frequencies were too small to allow for sensible estimation of proportion and standard errors.

In contrast, patterns in the estimates and confidence intervals for substance use outcomes could be distinguished more clearly, particularly with illicit drugs, where there was a tendency for risk to increase if cannabis use at 20 years was higher. For example, adolescent occasional cannabis users who progressed to weekly+ use at 20 years were more likely to meet criteria for cannabis dependence and use other illicit drugs at 24 years than occasional cannabis users who did not escalate their use.

Young adult outcomes according to level of adolescent cannabis use

Adolescent cannabis users were less likely than non-users to have gained post-school qualifications by 24 years (Table 2). This association remained after adjustment for background factors and adolescent alcohol use and depressive symptoms, but further adjustment for adolescent cigarette smoking substantially reduced the association (Table 2). Similarly, the association between weekly+ cannabis use and government welfare at 24 years was reduced after additional adjustment for adolescent smoking.

Table 2 Association of cannabis use in adolescence with psychosocial outcomes and substance use at 24 years in 1520 cohort participants, adjusted progressively for: gender; gender, background factors, adolescent depression and alcohol use; and gender, background factors, adolescent depression, alcohol use and cigarette smoking

| Outcome at 24 years (wave 8) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial outcomes | Licit substance use | Illicit substance use | ||||||

| Maximum level of adolescent cannabis use (waves 1-6) | Post-school qualificationsa (n = 1130) | Government welfare (n = 120) | Depression/anxiety (GHQ > 2) (n = 321) | Alcohol dependence (n = 187) | Nicotine dependence (n = 147) | Any cannabis use (n = 508) | Cannabis dependence (n = 111) | Other substances (n = 236) |

| No use (n = 999) | ||||||||

| n (%)b | 786 (79) | 67 (7) | 204 (20) | 187 (9) | 55 (5) | 216 (22) | 15 (1) | 108 (11) |

| OR | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Occasional use (n = 331) | ||||||||

| n (%) | 230 (70) | 26 (8) | 75 (23) | 50 (15) | 50 (15) | 154 (46) | 33 (10) | 92 (28) |

| Model 1,c OR (95% CI) | 0.63 (0.47-0.83) | 1.2 (0.73-2.1) | 1.2 (0.88-1.7) | 1.6 (1.1-2.4) | 3.1 (2.0-4.8) | 3.0 (2.3-4.0) | 7.1 (3.5-14) | 3.1 (2.1-4.4) |

| Model 2,d OR (95% CI) | 0.69 (0.51-0.91) | 1.2 (0.68-2.0) | 1.2 (0.81-1.6) | 1.5 (1.0-2.3) | 2.8 (1.7-4.4) | 2.9 (2.2-3.9) | 6.4 (3.2-13) | 2.9 (2.1-4.2) |

| Model 3,e OR (95% CI) | 0.98 (0.71-1.3) | 0.97 (0.55-1.7) | 0.94 (0.65-1.4) | 1.3 (0.82-2.0) | 1.3 (0.79-2.1) | 2.2 (1.6-3.0) | 4.0 (1.9-8.4) | 2.4 (1.6-3.6) |

| Weekly+ use (n = 190) | ||||||||

| n (%) | 113 (60) | 27 (14) | 42 (22) | 43 (23) | 42 (22) | 139 (73) | 55 (29) | 114 (60) |

| Model 1,c OR (95% CI) | 0.41 (0.29-0.58) | 2.4 (1.3-4.3) | 1.3 (0.85-1.9) | 2.6 (1.7-4.0) | 5.0 (3.2-7.7) | 9.3 (6.3-14) | 25 (13-47) | 12 (8.1-17) |

| Model 2,d OR (95% CI) | 0.50 (0.34-0.73) | 2.1 (0.97-4.4) | 1.2 (0.77-1.8) | 2.2 (1.3-3.6) | 3.9 (2.4-6.4) | 8.6 (5.7-13) | 21 (11-41) | 11 (7.2-16) |

| Model 3,e OR (95% CI) | 0.84 (0.55-1.3) | 1.6 (0.68-3.7) | 0.88 (0.55-1.4) | 1.7 (0.95-2.9) | 1.3 (0.77-2.3) | 5.6 (3.5-9.0) | 10 (4.7-22) | 7.8 (4.9-12) |

Both alcohol and nicotine dependence at 24 years occurred more often among adolescent cannabis users, with occasional users intermediate in risk level between non-users and weekly+ users. However, adjustment for adolescent cigarette use accounted almost entirely for these associations.

All drug use outcomes at 24 years were more common among adolescent cannabis users than non-users, even after adjustment. Occasional adolescent cannabis users were at a risk that was intermediate between the non-users and the more frequent users.

Discussion

Different levels and trajectories of adolescent cannabis use were associated with different risks for drug use in young adulthood. Those who were, or became, heavier users were at greatest risk, whereas those who maintained a stable, occasional pattern of use – the most populous group of adolescent-onset cannabis users – were at less marked, but still elevated, risk of drug use problems at age 24 years. Occasional users in adolescence who persisted with occasional use were at higher risk for drug use and drug use problems than non-users and those who only began occasional use after adolescence.

Occasional adolescent cannabis use was associated with lower educational attainment, but this association was substantially attenuated after adjustment for adolescent tobacco use. It seems unlikely that tobacco smoking directly affects educational attainment but this finding does raise a possibility that the social milieu linked to both tobacco smoking and cannabis use may contribute to such outcomes. Reference Mathers, Toumbourou, Catalano, Williams and Patton18 A recent study suggested that peer and parental influences that are linked to smoking during adolescence also predict poor school grades and thus smokers were more likely to have poorer academic outcomes. Reference Tucker, Martinez, Ellickson and Edelen19

Adolescent cannabis use has become normative in many countries. In some, it may be linked to social competence, popularity and exploration of new experiences; in others, it may reflect low family connection, low school commitment and affiliation with a similarly disengaged peer group. Conversely, abstention may be the result of social reservedness. Reference Shedler and Block4,Reference Tucker, Ellickson, Collins and Klein5,Reference Suris, Akre, Berchtold, Jeannin and Michaud20 Continued occasional cannabis use was not related to later depression/anxiety. In contrast, early and continued occasional cannabis use did predispose to later drug use.

This study was consistent with well-conducted, population-based cohort study findings that the timing of cannabis use onset may also be important. Reference Brook, Balka and Whiteman21,Reference Kandel, Yamaguchi and Chen22 Importantly, the current study found that even if early-onset cannabis use began and remained as occasional use, nonetheless, risks for drug use and drug use problems remained elevated. By studying the varying trajectories of use, this study has suggested that although a clear dose–response relationship exists between cannabis use and other outcomes, whereby regular users were most likely to have adverse outcomes during young adulthood, occasional adolescent-onset cannabis use that persists into young adulthood is clearly related to increased risks of some adverse outcomes, particularly drug use. The link between early-onset cannabis use and subsequent drug involvement – the so-called ‘gateway effect’ – has been the subject of much debate. Reference Hall23–Reference Morral, McCaffrey and Paddock25 Disagreement remains about the reasons why such associations persist, but researchers have proposed biochemical explanations that suggest that early-onset drug use might affect the maturing adolescent brain such that the user becomes more sensitive to (or disposed towards) other drug effects. Reference Schenk and Kandel26 Others suggest that learning and socially mediated processes are more important, whereby young users simply ‘learn’ to incorporate drug use into their lives and/or that use is accompanied by entry into social circles that are characterised by multiple types of drug use. Reference Hall23–Reference Morral, McCaffrey and Paddock25 Our findings regarding occasional use might be considered to be more consistent with psychosocial rather than biochemical mediation for the association, given the relatively infrequent exposure to the drug itself. Reference Schenk and Kandel26

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of this study are its population-based sample and the frequent detailed measures of drug use and psychosocial outcomes over a 10-year period. One limitation is that non-response in longitudinal studies is associated with drug use; however, we had relatively high participation rates and used multiple imputation to attempt to minimise non-response biases. All data were based on self-report which was not externally validated, but this has been accepted as an appropriate way in which to gain information about population behaviours. Reference Fendrich, Mackesy-Amiti, Johnson, Hubbell and Wislar27,Reference Harrison28 There were also no negative consequences for admitting to drug use. Reference Harrison28

Some cannabis use may not have been ‘captured’ within assessment windows in the adolescent waves owing to the 6-month timeframes. This is probably minimal because of the very high levels of cannabis use that were nonetheless documented, and the similarity in levels compared with other young people assessed in Australia around the same timeframe. 29 Wave 8 cannabis dependence may have been underestimated since only weekly+ users were assessed. However, comparison with Australian survey data found this was unlikely to occur. Reference Coffey, Carlin, Degenhardt, Lynskey, Sanci and Patton30 Finally, the small size of some groups limited the precision of some comparisons.

Implications

Occasional adolescent cannabis use was associated with higher levels of drug use in young adulthood compared with non-users. The confounding effect of tobacco use for a number of outcomes suggests possible mediating effects of underlying risk-taking behaviours in increasing risk for some adverse psychosocial outcomes. Exaggerated messages about severe harms of occasional cannabis use would be unfounded and at odds with the experience of this group. Yet interventions to reduce escalation of both cannabis and other drug use among occasional users do seem warranted. Given that occasional users are unlikely to present to specialised services, this message might be best delivered through screening in primary care or community-level health education. Reference Toumbourou, Stockwell, Neighbors, Marlatt, Sturge and Rehm31

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.