Previous studies have suggested (serotonergic) neurotoxicity of the recreational drug ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, MDMA). Reference Reneman, de Win, van den Brink, Booij and den Heeten1,Reference Parrott2 However, given that most ecstasy users are polydrug users, these findings are still debated as few have adequately controlled for this. Reference Schuster, Lieb, Lamertz and Wittchen3 The current study, part of The Netherlands XTC Toxicity (NeXT) study, Reference de Win, Jager, Vervaeke, Schilt, Reneman, Booij, Verhulst, den Heeten, Ramsey, Korf and van den Brink4 was designed to control for polydrug use by including a sample that varied in the type and amount of drugs used. The relatively low correlations between the use of ecstasy and other substances allowed for the use of linear multiple regression analysis to differentiate between the effects of ecstasy and of other substances without problems of multicollinearity. A combination of both single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques was used to simultaneously assess structural and functional aspects of potential ecstasy-induced neurotoxicity.

Method

Participants

In total, 71 participants (44 male, 27 female; mean age 23 years, s.d.=3.8, range 18–37) were included. A detailed description of the recruitment procedure can be found in a special design paper on the NeXT study. Reference de Win, Jager, Vervaeke, Schilt, Reneman, Booij, Verhulst, den Heeten, Ramsey, Korf and van den Brink4

Recruitment aimed to include a sample of individuals with variations in the amount and type of drugs used to keep correlations between the different drugs as low as possible. Potential candidates interested in participating in the study were asked to fill out a questionnaire on their drug use, but were masked to the inclusion criteria. Besides the typical heavy polysubstance ecstasy users, preference was given to candidates who were either ‘selective ecstasy users’ (100 ecstasy pills or more lifetime, but no or almost no use of other drugs except for cannabis) or ‘polydrug-but-no-ecstasy users’ (extensive experience with amphetamine and/or cocaine, but (almost) no ecstasy use, i.e. <10 pills lifetime). In the end, the sample included 33 heavy ecstasy users and 38 non-ecstasy users, with both ecstasy users and non-ecstasy users showing considerable variation in type and amount of other drugs taken, for example some heavy ecstasy users reported minimal use of other drugs such as cannabis, amphetamine or cocaine, whereas others were moderate or frequent users of one or more other psychoactive drugs. Similarly, some ecstasy-naïve individuals used no drugs at all, whereas other ecstasy-naïve individuals reported incidental or frequent use of amphetamine and/or cocaine and/or cannabis. Individuals were recruited using a combination of targeted site sampling, advertisement and snowball sampling. All participants had to be between 18 and 35 years of age. Exclusion criteria included severe medical or neuropsychiatric disorders; use of psychotropic medications affecting the serotonin system; pregnancy; use of intravenous drugs; and contraindications for MRI. Participants had to abstain from using psychoactive substances for at least 2 weeks and from alcohol for at least 1 week before examinations. Pre-study abstinence was checked with urine drug screening (enzyme-multiplied immunoassay for amphetamines, MDMA, opioids, cocaine, benzodiazepines, cannabis and alcohol).

Besides SPECT and MRI, individuals underwent functional MRI and cognitive testing reported in separate publications. Reference Jager, de Win, van der Tweel, Schilt, Kahn, van den Brink, van Ree and Ramsey5,Reference Schilt, Win, Jager, Koeter, Ramsey, Schmand and van den Brink6 Participants were paid to participate (€150 for 2 days). The study was approved by the local medical ethics committee and written informed consent from each person was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Assessment of ecstasy use and potential confounders

Lifetime use of ecstasy (number of tablets), cannabis (number of ‘joints’), amphetamines (number of occasions), cocaine (number of occasions), and use of alcohol (units/week) and tobacco (cigarettes/week) were assessed using substance-use questionnaires and the Substance Abuse Scales of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI, version 5) Reference Van Vliet, Leroy and van Megen7 for DSM–IV clinical disorders. Hair samples were collected from all but 19 participants (hair too short or hair dyed) for analysis on previous ecstasy use (gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy). Hair analyses (n=52) confirmed previous ecstasy use in 86% of individuals who reported to have used ecstasy. In addition, results from hair analyses showed no evidence for previous use of ecstasy in 96% of participants who had reported being ecstasy-naïve. Altogether, agreement between self-reported ecstasy use and ecstasy use according to hair analyses was 90%, resulting in a kappa of 0.81, which represents excellent overall chance adjusted agreement. Verbal IQ was estimated using the Dutch version of the National Adult Reading Test. Reference Nelson8

MRI acquisition and post-processing

Acquisition

Magnetic resonance imaging was performed on a 1.5 T scanner (Signa Horizon, LX 9.0, General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) using the standard head coil. Acquisition, post-processing and quality control were performed with the same methods as used in another substudy of the NeXT study. Reference de Win, Reneman, Jager, Vlieger, Olabarriaga, Lavini, Bisschops, Majoie, Booij, den Heeten and van den Brink9 For completeness, we have summarised the most relevant aspects of the employed methods. The protocol included axial proton density- and T2-weigthed imaging; three voxel-based proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) scans; diffusion tensor imaging; perfusion-weighted imaging; and high-resolution T1-weigthed 3D imaging. The 1H-MRS voxels were placed in the left centrum semiovale (frontoparietal white matter) and in mid-frontal and mid-occipital grey matter in analogy to previous studies. Reference Chang, Grob, Ernst, Itti, Mishkin, Jose-Melchor and Poland10,Reference Reneman, Majoie, Flick and den Heeten11 Throughout the study, positioning of participants in the scanner and positioning of the slices and voxels were performed by the same examiner and according to protocol in order to keep positioning as reproducible as possible.

Post-processing

Spectra derived from 1H-MRS were analysed using Linear Combination of Model spectra (LCModel). Reference Provencher12 Ratios of N-acetylaspartate (NAA; neuronal marker), choline (Cho; reflecting cellular density) and myoinositol (mI; marker for gliosis) relative to (phospho)-creatine (Cr) were calculated.

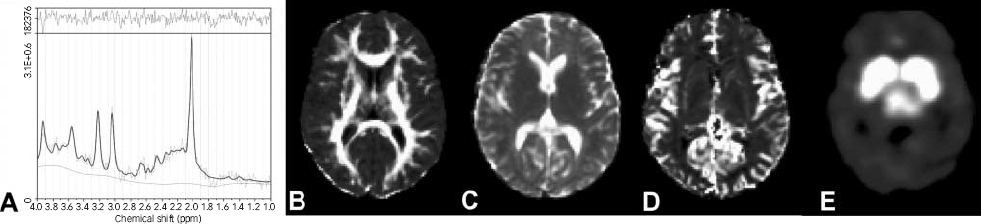

Apparent diffusion coefficient and fractional anisotropy maps were calculated from the diffusion tensor imaging Reference Hunsche, Moseley, Stoeter and Hedehus13 and cerebral blood volume maps from the perfusion-weighted imaging scans. Fractional anisotropy, apparent diffusion coefficient and cerebral blood volume were spatially normalised by registration to the Montreal Neurological Institute brain template (MNI152), and segmentation was performed to separate into cerebral spinal fluid, white and grey matter (Fig. 1). The cerebral blood volume maps were intensity-scaled to mean individual cerebral blood volume intensity of white matter derived from the segmentation procedure to generate relative cerebral blood volume maps.

Fig. 1 Representative images of an individual (a) 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy after analysis by Linear Combination of Model spectra and representative (b) fractional anisotropy; (c) apparent diffusion coefficient; (d) regional relative cerebral blood volume; and (e) [123I]β-CIT binding images after transformation to the spatially normalised Montreal Neurological Institute brain template.

Regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn on the MNI152 brain template in thalamus, putamen, globus pallidus, head of the caudate nucleus, centrum semiovale (frontoparietal white matter), and dorsolateral frontal, mid-frontal, occipital, superior parietal, and temporal cortex (Fig. 2). Only grey matter voxels were included for the cortical ROIs, whereas white and grey matter voxels were included for the ROIs of the basal ganglia (i.e. excluding cerebral spinal fluid voxels). Selection of ROIs was based on findings of previous studies, which indicated that ecstasy-induced abnormalities are most prominent in basal ganglia and certain cortical areas; ecstasy-induced abnormalities in white matter were rarely reported and thus not expected. As cortical grey matter has very low anisotropy, it is very difficult to get reliable fractional anisotropy and apparent diffusion coefficient measurements in cortical areas. For this reason, only ROIs in white matter and basal ganglia were taken into account in the measurements of fractional anisotropy and apparent diffusion coefficients. Within the ROIs, individual mean values of fractional anisotropy, apparent diffusion coefficient, and regional relative cerebral blood volume (rrCBV) were calculated. Values of fractional anisotropy, apparent diffusion coefficient and rrCBV from ROIs in left and right hemispheres were averaged.

Fig. 2 Regions of interest used for analyses of diffusion tensor imaging and perfusion-weighted imaging scans drawn on magnetic resonance brain template at three levels. 1, thalamus; 2, globus pallidus; 3, putamen; 4, caudate nucleus; 5, dorsolateral frontal cortex; 6, mid-frontal cortex; 7, occipital cortex; 8, superior parietal cortex; 9, temporal cortex; 10, white matter of the centrum semiovale.

SPECT acquisition and post-processing

Acquisition

In a subgroup of the population (n=47) SPECT imaging was performed with the radioligand [123I]2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl)-tropane ([123I]β-CIT) that binds to serotonin transporters, dopamine transporters and, to a lesser extent, noradrenaline transporters. The procedure of radiosynthesis of [123I]β-CIT and acquiring of SPECT images were the same as previously described. Reference de Win, Habraken, Reneman, van den Brink, den Heeten and Booij14 A bolus of approximately 110 MBq (3 mCi) [123I]β-CIT was injected intravenously and SPECT images were acquired 4 h after the injection, when stable specific uptake to serotonin transporters is expected to be reached. Reference de Win, Habraken, Reneman, van den Brink, den Heeten and Booij14

Post-processing

Attenuation correction of all images was performed as previously described. Reference de Win, Habraken, Reneman, van den Brink, den Heeten and Booij14 Images were reconstructed in 3D mode (www.neurophysics.com). All SPECT scans were registered (rigid body) to the T1-3D MRI scans of the same participant using a software package developed for 3D and 4D registration of multiple scans for radiotherapy application. Reference Wolthaus, van Herk, Muller, Belderbos, Lebesque, de Bois, Rossi and Damen15 Next, the same program was used to register the individual MRI scans to the MNI152 brain using affine transformations. For both registration steps an algorithm was used that maximises mutual information of the voxels of the scans to be registered. Reference Maes, Collignon, Vandermeulen, Marchal and Suetens16 Finally, the software package was used to resample the individual SPECT images to the MNI152 brain (Fig. 1), resulting in 91×109×92 voxel images with voxel sizes of 2×2×2mm3. In this way, all SPECT images could be analysed together.

For quantification, both ROI and voxel×voxel analyses were performed. For the ROI analysis, regions were drawn on the MNI152 template in midbrain, thalamus and temporal, frontal and occipital cortex. We did not measure serotonin transporter uptake in the putamen, caudate nucleus and globus pallidus, because there is no specific uptake to serotonin or dopamine transporters in these regions 4 h after [123I]β-CIT injection. Activity in the cerebellum was assumed to represent non-displaceable activity (non-specific binding and free radioactivity). Specific to non-specific binding ratios were calculated as (activity in ROI–activity in cerebellum)/activity in cerebellum. The image registration was visually inspected to check its quality.

For the voxel×voxel analysis, the Statistical Parametric Mapping software (SPM2, Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, Functional Imaging Laboratory, London, UK; www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) was used. Reference Friston, Holmes, Worsley, Poline, Frith and Frackowial17 The registered scans were intensity-scaled to the corresponding mean cerebellar non-specific counts per voxel. The mean cerebellar counts were obtained from the ROI analysis. Then, smoothing was applied with SPM2 (Gaussian kernel with a 16 mm full width at half maximum) to reduce inter-individual anatomical differences that remained after stereotactical normalisation. Reference Worsley, Marrett, Neelin and Evans18

Statistical analyses

Substance use variables and potential confounders

Self-reported histories of drug use may not be fully accurate and there is variation in the amount of MDMA in different ecstasy tablets. In addition, drug use variables in the current study were not normally distributed, not even after log transformation. Therefore, drug use variables were dichotomised using cut-off scores, which were fixed to balance the distribution of users and non-users of a particular drug. For ecstasy, amphetamines and cocaine the cut-off score was arbitrarily determined at >10 tablets/occasions lifetime. For cannabis, the cut-off score was set higher (>50 joints lifetime), because experimenting with cannabis is much more common than with other illicit drugs. Table 1 shows cut-off values, frequency distributions, means (s.d.) and medians for the substance variables in the total sample.

Table 1 Demographic features and drug usage patterns for the whole sample a (n=71)

| Variable | Cut-off value | Participants, n | Mean (s.d.) | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 44 | ||||

| Female | 27 | ||||

| Age, years | 71 | 23.3 (3.8) | 22.6 | 18–37 | |

| IQ (DART score) | 71 | 101 (7.7) | 100 | 83–122 | |

| Ecstasy users | >10 tablets lifetime | 33 | 322 (354) | 250 | 15–2000 |

| Amphetamine users | >10 occasions lifetime | 18 | 151 (154) | 120 | 15–600 |

| Cocaine users | >10 occasions lifetime | 22 | 72 (70) | 43 | 12–300 |

| Cannabis users | >50 joints | 42 | 1234 (1622) | 688 | 56–6650 |

| Alcohol users | >10 units per week | 36 | 22 (12) | 22 | 12–60 |

| Tobacco users | >10 cigarettes per week | 32 | 85 (46) | 80 | 17–200 |

DART, Dutch version of the National Adult Reading Test

a. Mean (s.d.), median and range for the different drugs show only values from individuals classified as users

Phi coefficients were calculated to assess the associations between dichotomised drug-use and demographic variables (Table 2). The relatively low association between some independent variables does not affect the validity of the regression model, because each regressor is adjusted for the predictive effect of all other regressors in the model. The variance inflation factor was used to estimate multicollinearity. In the various analyses, variance inflation factor values ranged from 1.0 to 1.7, indicating that factor correlations did not cause over-specification of the regression model, allowing for reliable estimation of the independent effects of the various drugs on the neuroimaging parameters.

Table 2 Phi correlations between dichotomised substance use variables in the whole sample a (n=71)

| Age | Gender | DART IQ | Alcohol | Tobacco | Ecstasy | Amphetamine | Cocaine | Cannabis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

| Gender | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | ||

| DART IQ | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | –0.23 | |||

| Alcohol | NS | NS | NS | NS | 0.38 | ||||

| Tobacco | 0.40 | NS | 0.31 | 0.41 | |||||

| Ecstasy | 0.43 | 0.54 | NS | ||||||

| Amphetamine | 0.45 | NS | |||||||

| Cocaine | NS | ||||||||

| Cannabis | NS |

DART, Dutch version of the National Adult Reading Test; NS, not significant

a. Substance use variables are dichotomised (0=below cut-off value, 1=above cut-off value; see Table 1 for classification criteria)

Gender was included in all regression analyses because previous studies indicated that females are more vulnerable to the effects of ecstasy than males. Reference Reneman, de Win, van den Brink, Booij and den Heeten1 The most important potential drug-use confounders amphetamine, cocaine and cannabis were included in all adjusted regression analyses. Additional confounders (age, verbal IQ, alcohol, tobacco) were chosen based on theoretical grounds per modality to reduce the number of regressors in the regression model: for 1H-MRS, verbal IQ was added as an additional confounder because a relationship between brain metabolites and verbal IQ was reported; Reference Jung, Brooks, Yeo, Chiulli, Weers and Sibbitt19 for diffusion tensor imaging no additional confounders were included in the analyses; and for perfusion-weighted and SPECT imaging, tobacco was added because previous studies showed a relationship between smoking and brain perfusion, Reference Zubieta, Heitzeg, Xu, Koeppe, Ni, Guthrie and Domino20 as well as between smoking and serotonin transporter densities. Reference Staley, Krishnan-Sarin, Zoghbi, Tamagnan, Fujita, Seibyl, Maciejewski, O'Malley and Innis21 Age was not included as a confounder, because of the relatively small age-range within the sample.

Linear regression MRI and SPECT region of interest analyses

To assess the specific effects of ecstasy and contributions of other drugs on the outcome parameters of MRI and SPECT imaging, linear multiple regression analyses were performed. Two different stepwise multiple linear regression models were used with imaging parameters as dependent variables.

Model 1 estimated the upper bound effect of ecstasy on outcome parameters, i.e. with adjustment for the effects of gender (and also verbal IQ in the case of 1H-MRS), but without correction for the effects of other drugs. In the first step, gender (and IQ) was entered as the independent variable and in a second step, ecstasy was entered. The effect of ecstasy was quantified as the R 2-change between the first and the second steps of the model. This model resembles the approach in previous studies that compared ecstasy users with non-users. However, the effect of ecstasy in this model is likely to be an overestimation of the real independent effect of ecstasy owing to the lack of correction for the impact of other drugs on the imaging parameters of neurotoxicity.

Model 2 estimated the lower bound effect of ecstasy on outcome parameters after adjustment for the effects of gender, IQ and the use of substances other than ecstasy. In analogy to model 1, first gender (and IQ in the case of 1H-MRS) and substance use other than ecstasy (cannabis, amphetamines and cocaine in all analyses and tobacco in the case of perfusion-weighted imaging and SPECT) were entered in the model as independent variables. In a second step, ecstasy was entered as an additional independent variable. Similar to model 1, the independent effect of ecstasy use was quantified as the R 2-change between the first and second steps of the model. The effect of ecstasy in model 2 is presumably an underestimation of the real independent effect of ecstasy, because of possible over-correction for the effects of other drugs.

Linear regression analyses were performed using SPSS version 11.5 for Windows. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Besides R 2, unstandardised regression coefficients (B) were used to reflect the predictive power of the different regressors. In the online Table DS1, B values are reported with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and in the text with their two-tailed significance level (P value).

SPECT voxel×voxel analysis

For the voxel×voxel analyses we did not use the sample as a whole as in the other analyses (because in SPM it was not possible to perform similar voxel-based linear regression analyses in the sample as a whole as for the ROI analyses), but divided the sample (n=47) into five groups, based upon the dichotomised drug-use variables (Table 1). The groups included: heavy ecstasy polydrug users (n=10); selective ecstasy and cannabis users (n=4); ecstasy-naïve polydrug (amphetamine and/or cocaine and cannabis) users (n=5); ecstasy-naïve cannabis users (n=16); and drug-naïve controls (n=12). The [123I]β-CIT binding ratios of the stereotactically and intensity-normalised and smoothed SPECT images were compared between the five groups on a voxel×voxel basis by means of the spatial extent statistical theory using SPM2. Reference Friston, Holmes, Worsley, Poline, Frith and Frackowial17,Reference Worsley, Marrett, Neelin and Evans18 The positron emission tomography (PET)/SPECT model ‘single subject conditions and covariates’ was chosen. Five conditions and no covariates were included. The main comparison was between ecstasy users and non-users (groups 1 and 2 v. groups 3, 4 and 5). Because this showed some significant clusters, post hoc comparisons were made between the different groups to analyse whether significant differences were caused by ecstasy or by other substances. An effect was considered statistically significant if a cluster of at least 20 connected voxels reached a P value <0.001 (one-sided; T=3.30, uncorrected for multiple comparisons). Clusters of voxels surviving the thresholds were colour-coded and superimposed on the MNI152 template.

Results

Sample characteristics and substance use

Characteristics of demography and substance use of the total sample are presented in Table 1. Mean cumulative dose of ecstasy within the ecstasy group was 322 tablets (s.d.=354). Mean time since last ecstasy use within this group was 8.2 weeks (s.d.=9.8), age at first use 17.7 years (s.d.=2.8) and usual ecstasy dose was 2.7 tablets per session (s.d.=1.6).

1H-MRS, diffusion tensor imaging and perfusion-weighted imaging

Two participants had enlarged lateral ventricles (one ecstasy-naïve cannabis user and one ecstasy polydrug user), hampering matching to the MNI template, so the diffusion tensor imaging and perfusion-weighted imaging of these people were not included. Owing to technical problems, 1H-MRS was not performed in two individuals and diffusion tensor imaging in one person. Therefore, we report measurements of 1H-MRS and rrCBV in 69 participants and of fractional anisotropy and apparent diffusion coefficient in 68 participants.

Online Table DS1 shows results from the linear regression analyses. There was no significant effect of ecstasy use on the brain metabolites ratios NAA/Cr, Cho/Cr and mI/Cr in any of the three regions. With diffusion tensor imaging no significant effects of ecstasy on apparent diffusion coefficient in basal ganglia were observed, but ecstasy did have a significant negative effect on fractional anisotropy in the thalamus (model 1: R 2 ecstasy=16.6%; B ecstasy=–20.09, P<0.001). After adjusting for other drugs, the negative effect of ecstasy on thalamic fractional anisotropy remained significant (model 2: R 2 ecstasy=9.7%; B ecstasy=–18.76, P=0.006). Also, gender had a significant effect on fractional anisotropy in the thalamus (lower in females) (B gender=–11.95, P=0.043). Ecstasy had a significant positive effect on rrCBV in the thalamus (model 1: R 2 ecstasy=7.3%; B ecstasy=0.094, P=0.024) and the temporal cortex (model 1: R 2 ecstasy=8.1%; B=0.111, P=0.018). These effects remained statistically significant after correction for other substances (model 2: R 2 ecstasy=6.4%; B ecstasy=0.114, P=0.037 for the thalamus and R 2 ecstasy=6.8%; B ecstasy=0.131, P=0.030 for the temporal cortex).

According to model 2, amphetamine had a positive effect on mid-occipital mI/Cr ratios (B amphetamine=0.085, P=0.031), a negative effect on fractional anisotropy in the centrum semiovale (B amphetamine=–24.53, P=0.033) and a negative effect on rrCBV in the superior parietal cortex (B amphetamine=–0.109, P=0.038). Use of cocaine had a positive effect on both Cho/Cr (B cocaine=0.027, P=0.030) and mI/Cr (B cocaine=0.144, P=0.004) ratios in the centrum semiovale, whereas cocaine had a negative effect on Cho/Cr in the mid-frontal cortex (B cocaine=–0.027, P=0.036). Cannabis did not have any significant effect on magnetic resonance outcome parameters.

[123I]β-CIT SPECT

Region of interest analyses showed a significant negative effect of ecstasy on [123I]β-CIT binding in the thalamus (model 1: R 2 ecstasy=31.0%; B ecstasy=–0.394, P<0.001), frontal cortex (model 1: R 2 ecstasy=16.4%; B ecstasy=–0.090, P=0.005) and temporal cortex (model 1: R 2 ecstasy=21.1%; B ecstasy=–0.160, P=0.001) (online Table DS1). After adjustment for amphetamines, cocaine, cannabis and tobacco (model 2), the effect remained significant in the thalamus (R 2 ecstasy=15.2%; B ecstasy=–0.343, P=0.003), but not in the frontal and temporal cortex (P=0.140 and P=0.076 respectively). Amphetamine, cocaine and cannabis use did not have significant effects on [123I]β-CIT binding in any of the ROIs.

Also with voxel×voxel analysis, lower [123I]β-CIT binding was observed in the thalamus of ecstasy users compared with non-users (Z max=5.07, P corrected, cluster-level=0.001; coordinates of the highest Z-value: 2, −22, 8) (online Fig. DS1). The degree of [123I]β-CIT binding in the cingulate gyrus was also significantly lower in ecstasy users than in non-users, although this should be interpreted with caution, because the highest Z-value was exactly in the midline (Z max=4.15, P corrected, cluster-level<0.001; coordinates of the highest Z-value: 0, 42, 8). post hoc, the same cluster of significantly lower [123I]β-CIT binding in the thalamus was observed in ecstasy users when we compared ecstasy users with substance-using controls (groups 1 and 2 v. groups 3 and 4), when we compared ecstasy polydrug users with ecstasy-naïve polydrug users (group 1 v. group 3), and when we compared selective ecstasy and cannabis users with ecstasy-naïve cannabis users (group 2 v. group 4). The cluster of significantly lower [123I]β-CIT binding in the anterior cingulate gyrus was observed in ecstasy users when we compared ecstasy users with substance-using controls (groups 1 and 2 v. groups 3 and 4) and when we compared selective ecstasy and cannabis users with ecstasy-naïve cannabis users (group 2 v. group 4), but not when we compared ecstasy polydrug users with ecstasy-naïve polydrug users (group 1 v. group 3). No clusters of increased [123I]β-CIT binding were observed in ecstasy users in any of the comparisons. Selective ecstasy and cannabis users did not have clusters of significantly different [123I]β-CIT binding than ecstasy polydrug users (group 1 v. group 2). Cannabis users did not significantly differ from drug-naïve controls (group 4 v. group 5), and ecstasy-naïve polydrug users did not differ on [123I]β-CIT binding from drug-naïve controls (group 3 v. group 5).

Discussion

Use of the party drug ecstasy has been associated with decreased serotonergic function as shown by decreased densities of serotonin transporters in membranes of serotonin axons, decreased neurocognitive performance, and increased depression scores in ecstasy users. Reference Reneman, de Win, van den Brink, Booij and den Heeten1,Reference Parrott2 The loss of transporters in serotonergic terminals most likely represents axonal injury, since preclinical studies show that ecstasy typically induces axonal injury/loss of serotonergic cells and that the serotonergic cell bodies remain intact. Reference Hatzidimitriou, McCann and Ricaurte22 However, the validity of findings suggesting ecstasy-related neurotoxicity in humans is debated because most studies have methodological limitations, including inadequate control of potential confounders such as polydrug use. The present study was designed to overcome limitations of previous studies, by adequately controlling for polydrug use and by combining, for the first time, advanced magnetic resonance and SPECT imaging techniques in the same sample to study different aspects of brain involvement.

Polydrug confounding in human ecstasy studies

Because almost all ecstasy users are polydrug users Reference Schuster, Lieb, Lamertz and Wittchen3 it is difficult to differentiate effects of ecstasy from potential effects of other psychoactive drugs. Some studies reported that signs of neurotoxicity in ecstasy users might be related not to ecstasy use alone but rather to polydrug use or the use of other psychoactive drugs such as cannabis, amphetamines or cocaine. Reference Gouzoulis-Mayfrank and Daumann23 Only some of the previous studies adequately controlled for use of drugs other than ecstasy by including a group of ‘pure’ ecstasy users, Reference Halpern, Pope, Sherwood, Barry, Hudson and Yurgelun-Todd24 by including a drug-using but ecstasy-naïve control group Reference Montgomery, Fisk, Newcombe and Murphy25 or by statistically adjusting for polydrug use. Reference Verkes, Gijsman, Pieters, Schoemaker, de Visser, Kuijpers, Pennings, de Bruin, Van de Wijngaart, van Gerven and Cohen26 However, these attempts have limitations because ‘pure’ ecstasy users are very rare Reference Schuster, Lieb, Lamertz and Wittchen3 and drug use in the control groups was generally lower than in the ecstasy groups and mainly comprised the use of cannabis and much less the use of amphetamines and cocaine. Controlling for polydrug use in a statistical regression analysis was generally hampered by the fact that cannabis, cocaine and amphetamine use were almost always strongly correlated with ecstasy use, leading to multicollinearity and the impossibility of statistical adjustment for these potential confounders in multiple regression analysis. Reference Verkes, Gijsman, Pieters, Schoemaker, de Visser, Kuijpers, Pennings, de Bruin, Van de Wijngaart, van Gerven and Cohen26

In our study we used a new approach by including a carefully selected sample of drug users with specific variations in amount and type of drugs used. This strategy successfully reduced the magnitude of the correlations between ecstasy use and the use of other substances, and allowed us to use linear multiple regression analysis to differentiate between the effects of ecstasy and of other substances.

Specific effects of ecstasy on the thalamus

The most interesting finding is that different imaging techniques all showed a specific effect of ecstasy on the thalamus. Even after adjustment for amphetamine, cocaine, cannabis and other relevant potential confounders, a significant effect of ecstasy, and no effects of any of the other drugs, was found on [123I]β-CIT binding (reduced), fractional anisotropy (reduced) and rrCBV (increased) in the thalamus. As [123I]β-CIT SPECT was previously validated to assess in vivo binding to serotonin transporters, the finding of decreased [123I]β-CIT binding probably reflects lower serotonin transporter densities in ecstasy users. Reference de Win, Habraken, Reneman, van den Brink, den Heeten and Booij14,Reference de Win, de Jeu, de Bruin, Habraken, Reneman, Booij and den Heeten27 Moreover, the thalamus is a serotonin transporter-rich area and previous studies showed that [123I]β-CIT binding in the thalamus is mainly related to transporter binding, although the thalamus also contains noradrenaline transporters. Diffusion tensor imaging measures diffusional motion of water molecules in the brain which is normally restricted in amplitude and direction by cellular structures such as axons. Reference Le Bihan, Turner, Douek and Patronas28 When axons are damaged, extracellular water content increases and fractional anisotropy decreases. Therefore, it is likely that the observed decreased fractional anisotropy is related to ecstasy-induced axonal injury. An alternative explanation could be that decreased fractional anisotropy relates to increased brain perfusion in the thalamus, which also gives an increase in extracellular water content. As ecstasy was previously shown to reduce extracellular serotonin and serotonin is involved in regulation of brain microcirculation, mainly as a vasoconstrictor, Reference Cohen, Bonvento, Lacombe and Hamel29 ecstasy-induced serotonin depletion may have led to vasodilatation and the observed increase in rrCBV. Taken together, it seems that these measurements in the thalamus converge in the direction of decreased serotonergic function, with decreased serotonin transporter binding and decreased fractional anisotropy values probably reflecting damage to serotonergic axons and increased rrCBV due to decreased vasoconstriction caused by depletion of serotonin. Previous studies in animals also showed ecstasy-induced axonal damage to the serotonergic axons of the thalamus, although signs of re-innervation after a period of recovery were also observed. Reference Ricaurte, Martello, Katz and Martello30 As the thalamus plays a key role in awareness, attention and neurocognitive processes such as memory and language, Reference Herrero, Barcia and Navarro31 one can speculate that ecstasy-induced serotonergic damage to the thalamus is (partly) responsible for reduced verbal memory performance frequently reported in ecstasy users.

Integration with prior SPECT/PET studies

Previous imaging studies in ecstasy users mainly used PET or SPECT techniques with tracers that bind to the serotonin transporter. Reference Reneman, de Win, van den Brink, Booij and den Heeten1 In line with the current study, almost all of these studies reported decreased binding in the thalamus of ecstasy users. However, most of these studies also reported lower serotonin transporter-binding in other subcortical and cortical areas, although these areas varied in different studies. When only adjusted for gender and not for other substances, we also observed lower [123I]β-CIT binding in ecstasy users in the frontal cortex, mainly located in the anterior cingulate gyrus as shown by the voxel×voxel analysis, and temporal cortex. However, decreased [123I]β-CIT binding in these areas seemed to be related to poly-drug use in general, and not to ecstasy or any other drug in particular, because none of the psychoactive substances was a significant predictor in the adjusted model. Moreover, decreased [123I]β-CIT binding ratios in areas with few serotonin transporters, such as the cortical areas, should be interpreted with caution. Reference de Win, Habraken, Reneman, van den Brink, den Heeten and Booij14 We did not observe decreased [123I]β-CIT binding in midbrain and occipital cortex as previously observed and we could not reproduce findings that women might be more susceptible than men to the effects of ecstasy on the serotonergic system. Reference Reneman, de Win, van den Brink, Booij and den Heeten1,Reference Parrott2 A recent PET study in patients who had previously been treated with the appetite suppressants fenfluramine and dexfenfluramine (known serotonergic neurotoxins in animals) also showed reductions in serotonin transporters, and these reductions were greatest in the thalamus. Reference McCann, Szabo, Vranesic, Seckin, Duval, Dannals and Ricaurte32 This finding is of particular interest since these patients had no or low exposure to drugs of misuse.

Integration with prior magnetic resonance studies

Only few previous studies used advanced magnetic resonance techniques to assess ecstasy-induced neurotoxicity. One preliminary study measured apparent diffusion coefficients in ecstasy users, although not in the thalamus, and reported an increased apparent diffusion coefficient in the globus pallidus of ecstasy users, suggesting axonal damage. Reference Reneman, Majoie, Habraken and den Heeten33 In our study we did not find any effect of ecstasy on apparent diffusion coefficient measurements, as would be expected, especially because we did find a decrease in fractional anistropy, which is often related to an increase in apparent diffusion coefficient. The same study of Reneman et al Reference Reneman, Majoie, Habraken and den Heeten33 (not including measurements in the thalamus) also examined brain perfusion and showed increased rrCBV values in the globus pallidus of ecstasy users. Another study by our group reported increased rrCBV values in the globus pallidus and thalamus of two former ecstasy users who had been abstinent for 18 weeks on average. Reference Reneman, Habraken, Majoie, Booij and den Heeten34 In our study we did not observe increased rrCBV values in the globus pallidus. However, we observed an increase in rrCBV, only related to ecstasy and not to other drugs, in the thalamus and also in the temporal cortex, an area that was not included in the previous studies. Cerebrovascular changes in ecstasy users were also observed in a previous SPECT study, measuring regional cerebral blood flow. Reference Chang, Grob, Ernst, Itti, Mishkin, Jose-Melchor and Poland10

With 1H-MRS, we did not find indications of neuronal damage (i.e. no decrease in NAA/Cr ratios and no increase in Cho/Cr and mI/Cr ratios in ecstasy users. However, we did not perform 1H-MRS in the thalamus, because it is technically difficult to obtain reliable 1H-MRS measurements in that area owing to magnetic field inhomogeneities and partial volume effects. Previous studies showed lower NAA/Cr ratios in the frontal cortex of ecstasy users with an average cumulated dose of more than 700 tablets, probably reflecting neuronal loss, whereas others found no difference in NAA/Cr ratios in cortical brain regions in individuals with more moderate lifetime doses. Reference Reneman, de Win, van den Brink, Booij and den Heeten1 Therefore, these effects may only become apparent after very heavy ecstasy (polydrug) use. On the other hand, a recent experimental study in non-human primates observed reductions in NAA in the hypothalamus even after low MDMA exposure. Reference Meyer, Brevard, Piper, Ali and Ferris35 An increased myoinositol in parietal white matter was observed in only one study. Reference Reneman, de Win, van den Brink, Booij and den Heeten1

Effects of other drugs

In addition to the effects of ecstasy, the current study design enabled us to explore effects of other substances on the outcome parameters. Amphetamine use, mainly D-amphetamine in The Netherlands, also showed some significant effects on the outcome parameters. However, the different imaging techniques showed effects of amphetamine in different brain areas, and therefore these findings are less consistent than the converging findings of the ecstasy effects on the thalamus. Amphetamine users showed an increased mI/Cr ratio in the mid-occipital grey matter and decreased fractional anisotropy in the centrum semiovale, and decreased rrCBV in the superior parietal grey matter. As it is known that D-amphetamine use is mainly associated with dopaminergic toxicity, Reference Booij, de Bruin and Gunning36 these effects may be related to damage of the dopaminergic system. Cocaine had a positive effect on Cho/Cr and mI/Cr ratios in the centrum semiovale, which might be related to increased glial activation. In contrast, cocaine had a negative effect on the Cho/Cr ratio in the mid-frontal grey matter. A previous study of cocaine users showed increased mI/Cr ratios in both frontal grey and white matter, as well as a decreased NAA/Cr ratio in the frontal cortex. Reference Chang, Ernst, Strickland and Mehringer37 Cocaine did not have any significant effect on outcomes of diffusion tensor imaging, perfusion-weighted imaging or SPECT measurements. Cannabis use had no significant effect on any of the outcome parameters. Also, other studies showed little evidence that chronic cannabis use causes permanent brain damage Reference Iversen38 or changes in cerebral blood flow, Reference Tunving, Thulin, Risberg and Warkentin39 although there are indications that mild cognitive impairment can occur in very heavy chronic cannabis use. Reference Solowij40

Limitations

Owing to its cross-sectional design and lack of baseline data it is difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding the causality of the observed relationships between ecstasy use and the neuroimaging outcome parameters, because it is possible that differences between ecstasy users and controls were pre-existent. We had to rely on the retrospective self-reported records of drug use in the past using drug-history questionnaires of which the reliability is uncertain. Hair analyses supported the plausibility of self-reported data on ecstasy use in our study, although it yields no information on patterns of ecstasy use, i.e. frequency, dosage or cumulative lifetime dose. There will also have been variation in dosage and purity of ecstasy tablets, although pill-testing confirms that in The Netherlands 95% of the tablets sold as ecstasy contain MDMA as a major component, as previously discussed. Reference de Win, Jager, Vervaeke, Schilt, Reneman, Booij, Verhulst, den Heeten, Ramsey, Korf and van den Brink4 Also, environmental circumstances under which ecstasy was taken and simultaneous use of other substances were heterogeneous. Because of our recruitment strategy, the current sample cannot be regarded as representative of all heavy ecstasy users. Therefore, the point estimate of the effect of ecstasy on the neurotoxicity parameters should be interpreted with caution. More important, the specific recruitment strategy allowed us to test whether the observed neurotoxic effect of ecstasy remained significant after statistical control for the use of other drugs such as cannabis, amphetamines and cocaine. Although we succeeded in creating relatively independent factors for ecstasy and cannabis use, correlations between use of ecstasy and amphetamine and cocaine were relatively low but still substantial and statistically significant. None the less, correlations between use of ecstasy and other illicit drugs were lower than usually found after random recruitment among frequent ecstasy users Reference Scholey, Parrott, Buchanan, Heffernan, Ling and Rodgers41 and statistical collinearity analyses did not suggest any problems of multicollinearity, indicating that the regression model allowed for reliable estimation of the effects of the various drugs. Moreover, the association between ecstasy use and its most commonly used co-drug, cannabis, was successfully removed as a result of sample stratification, thereby controlling for an important confounder. To prevent measuring acute pharmacological effects, participants had to abstain from psychoactive drugs for 2 weeks before examinations. This may have led to some inevitable selection, especially among heavy cannabis users. Finally, we did not correct for multiple comparisons in order to minimise the risk of false-negative results (type II errors). Reference Rothman42 The use of various imaging techniques and assessments in different brain regions may have introduced some false-positive findings (type I errors).

Acknowledgements

The NeXT study was supported by a grant of The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development as part of their Program Addiction (ZonMw 310-00-036). S.D.O. participates in the Virtual Laboratory for e-Science project, which is supported by a BSIK grant from the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. We thank Professor M. Moseley (Lucas MRS Center, Stanford University, USA) for support in the implementation of the diffusion tensor imaging protocol. We also thank Dirk Korf for his help on the design of the study; Hylke Vervaeke for recruiting volunteers; Sarah Dijkink and Ivo Bisschops for assistance with data collection; Jacco Visser and other technicians for making the SPECT scans; Benoit Faivre, Dick Veltman, Matthan Caan, Frans Vos, Marcel van Herk and Jan Habraken for their help in analysing the SPECT data; Erik-Jan Vlieger and Jeroen Snel for their help on the post-processing of the diffusion tensor imaging and perfusion-weighted imaging scans; Charles Majoie for reading all anatomical magnetic resonance scans; and Maarten Koeter and Ben Schmand for their advice on the statistical analysis.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.