A variety of cognitive deficits, especially verbal memory and general executive dysfunction, have been reported in people with bipolar disorder. Reference Savitz, Solms and Ramesar1 Nevertheless, effect sizes are small and findings differ across studies. Reference Robinson, Thompson, Gallagher, Goswami, Young and Ferrier2 Possible confounding variables are mood, medication, substance use and childhood abuse. Reference Savitz, van der Merwe, Stein, Solms and Ramesar3,Reference Savitz, van der Merwe, Stein, Solms and Ramesar4 Extant literature also suggests that a diathesis for the development of psychotic features (in the form of schizotypal personality traits) may have an impact on cognitive function. Reference Park, Holzman and Goldman-Rakic5 Approximately half of all patients with bipolar disorder present with psychotic features as defined by DSM–IV on at least one occasion, 6,Reference Keck, McElroy, Havens, Altshuler, Nolen and Frye7 and schizotypal personality traits have been noted to be salient in samples of people with the disorder. Reference Rossi and Daneluzzo8–Reference Schurhoff, Laguerre, Szoke, Meary and Leboyer10 In line with these data, patients with bipolar disorder reportedly display distinct cognitive profiles according to whether or not they have a history of psychotic features, Reference Glahn, Bearden, Barguil, Barrett, Reichenberg and Bowden11 although see the study by Bora et al. Reference Bora, Vahip, Akdeniz, Gonul, Eryavuz and Ogut12 This is a profoundly important issue because it goes to the heart of the nosological foundations of psychiatry. Significant differences in neurocognitive function between patients with bipolar disorder and remitted psychosis and those with no history of psychosis, not attributable to medication or another confound, would provide preliminary evidence for a nosological distinction between the two ‘subtypes’ of bipolar disorder, raising questions about the validity of categorical distinctions between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia-spectrum illness as defined in DSM–IV. 6

In this study we evaluated the performance of two groups of patients with bipolar disorder, one with and one without a history of psychotic features, on a battery of memory and executive tasks while controlling for mood, antipsychotic medication use, alcohol misuse/dependence and childhood trauma. Further, we examined the relationship between neuropsychological performance and possible predisposition to the development of psychotic features in the form of scores on the Schizotypal Personality Scale (STA). Reference Claridge and Broks13

Method

Sample

A cohort of 350 White individuals from 47 South African bipolar disorder pedigrees was recruited between 1997 and 2001 as part of a genetics research project. The criterion for recruitment was the presence of two or more affected first-degree relatives. Thereafter, pedigrees were enlarged if they provided genetically informative information. Probands and their relatives were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders (SCID–I). Reference First, Spitzer and Gibbon14 As in a number of other studies, Reference Glahn, Bearden, Barguil, Barrett, Reichenberg and Bowden11,Reference Bora, Vahip, Akdeniz, Gonul, Eryavuz and Ogut12 the lifetime presence or absence of psychotic features was evaluated during the diagnostic interview. Psychotic features were defined as the presence of hallucinations or delusions during manic or depressive episodes. Informed consent and ethics approval for the study was obtained.

In a follow-up study conducted between 2003 and 2005, a battery of neuropsychological tests was administered to 225 of the original participants. Reasons for sample attrition were as follows: remote location, 37 (10.5%); refusal to participate, 42 (12.0%); death, 22 (6.3%); emigration, 18 (5.1%); and confounding neurological condition (e.g. history of stroke), 6 (1.7%). Of this cohort, 49 participants were diagnosed with type I bipolar disorder and 61 of their relatives were unaffected. The latter group did not have any psychiatric diagnosis. Twenty-five of the participants with type I bipolar disorder had a positive history of psychosis (bipolar(+P) group) and 24 had no history of psychosis (bipolar(–P) group). Patients with a serious medical illness, a neurological disorder or any other condition (such as a head injury) that could affect cognition were excluded from the study. One participant had undergone electroconvulsive therapy approximately 6 weeks prior to the testing.

Psychometric testing

Well-validated neuropsychological tasks measuring various aspects of executive function and verbal and visual memory were given to the cohort. The mood state of the sample at the time of testing was measured with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (ASRM). Reference Beck and Steer15,Reference Altman, Hedeker, Peterson and Davis16 The neuropsychological assessment took approximately 1 h per person to complete and was administered in the following order: South African Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (SA–WAIS) Reference Claasen, Krynauw, Mathe and Paterson17 general knowledge sub-test (a measure of premorbid functioning); Digit Span forward and reverse (attention and verbal working memory); the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) for verbal fluency; the Rey Complex Figure (RCF) test (visual spatial functioning and visual memory); the Stroop Colour–Word test (cognitive control); the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) for verbal learning and memory; and the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) for cognitive flexibility and set-shifting. Details of these tests are available in standard texts such as that by Spreen & Strauss. Reference Spreen and Strauss18

For the RCF test, two variables were used in the analysis: RCF recall, which refers to the recall score obtained by the participant after the copy condition, and Snow's correction, which is the recall score controlled for the quality of the initial copy of the diagram. Concerning the RAVLT, the following variables were used in the analysis: learning rate, which is the score obtained in trial 1 subtracted from the score obtained in trial 5; total recall, which is the sum of the score obtained on the first five trials; and recognition, which refers to the ability of the participant to recognise the words that were learned after a distracter – in this case the WCST. Two variables were used from the Stroop test: number of words, which refers to the number of words read correctly during the interference condition of the task, and number of errors made by the participant during the interference condition. Four self-explanatory variables were derived from the WCST: number of categories obtained, trials taken to complete the first category, number of perseverative errors and failure to maintain cognitive set.

The BDI has been shown to be a reliable (test–retest r=0.74–0.93) and valid measure of depression. Reference Beck and Steer15 Scores of 10–18, 19–29 and 30 or more are indicative of mild, moderate and severe depression respectively. The ASRM correctly classified 85.5% of patients with mania (scores of 6 or more) and 87.3% of those without mania in the test development sample. The ASRM shows good test–retest reliability (r=0.86–0.89) and concurrent validity with other mania scales (r=0.718 and r=0.766). Reference Altman, Hedeker, Peterson and Davis16

Childhood abuse was measured with the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), Reference Bernstein, Stein, Newcomb, Walker, Pogge and Anluvalia19 a validated and widely used self-report instrument for both clinical and non-clinical populations. Correlations with therapist ratings of abuse were reported to be statistically significant for all five CTQ sub-scales (emotional, physical and sexual abuse, emotional and physical neglect), ranging from 0.36 to 0.75. Reference Spreen and Strauss18 In line with these data, Prescott et al found that actual observations of child–parent interactions correlate well with self-reported recollections of punitive experiences. Reference Prescott, Bank, Reid, Knutson, Burraston and Eddy20

Schizotypal personality traits were measured with the STA, Reference Claridge and Broks13 which is modelled on DSM–III criteria for schizotypal personality disorder. Unlike the categorical view of illness represented by the DSM, however, the STA makes the assumption that schizotypal traits, and therefore predisposition to psychotic breakdown, are a continuously distributed phenomenon in the population, and therefore the scale can be used on a normal population. Scores on the questionnaire range from 0 to 37. The scale has proved to discriminate well between people with a history of psychotic features and control groups, and test–retest correlations of 0.64 after 4 years have been reported. Reference Jackson and Claridge21 It has also been the subject of at least three independent principal component analyses which have identified three or four factors variously labelled as ‘magical thinking’, ‘unusual perceptual experiences’; ‘paranoid suspiciousness’ and ‘social anxiety’. Reference Jackson and Claridge21

Procedure

The majority of individuals were tested during the day in their own homes; a small number of study participants were assessed in a counselling room at the Division of Human Genetics at the University of Cape Town. Participants were in a stable condition, few having being recently hospitalised. Approximately 180 of the neuropsychological assessments were conducted by a neuropsychologist (J.S.). The balance were conducted by a psychiatric nurse and two graduate students who were trained in the administration of the task.

Statistical analysis

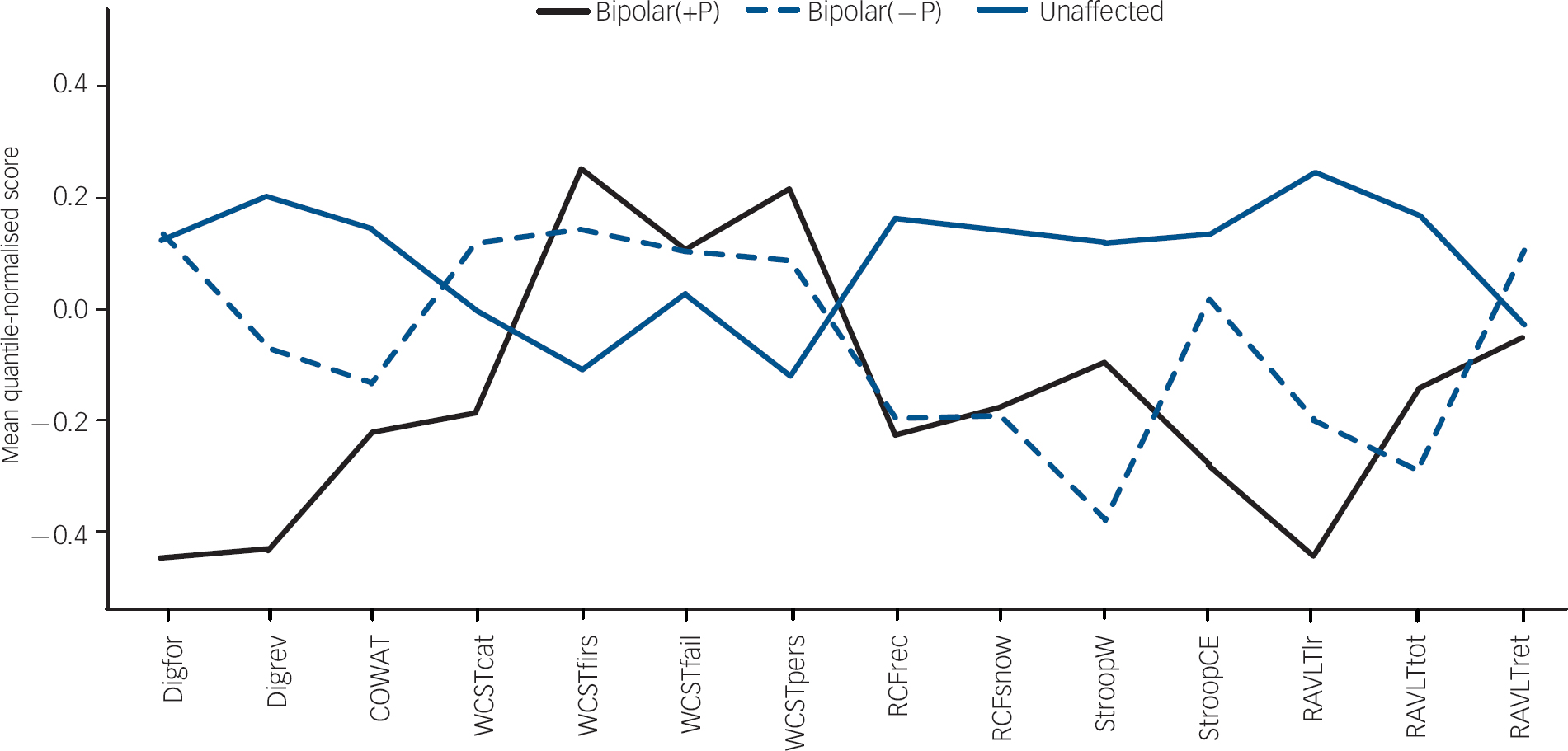

The statistical program R (www.r-project.org) was used for all statistical analyses. Because the distributions of some of the neuropsychological task scores were skewed, all scores are summarised with median and range. Most of the scales, such as RAVLT total recall, could be analysed as continuous variables, whereas three variables were discrete (counts) with a built-in maximum score of less than 10. All continuous scores were transformed to an approximate standard normal distribution with quantile normalisation as described by Pilia et al. Reference Pilia, Chen, Scuteri, Orru, Albai and Dei22 A graph comparing the means of the unadjusted transformed (quantile-normalised) continuous scores between the diagnostic groups was created to illustrate their relative sizes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Unadjusted means of quantile-normalised scores on neuropsychological tasks across the three diagnostic groups: bipolar disorder with psychosis (bipolar(+P)), bipolar disorder without psychosis (bipolar(–P)) and unaffected relatives. COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; Digfor, Digit Span forwards; Digrev, Digit Span reverse; RAVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (lr, learning rate; rec, recognition; tot, total recall); RCF, Rey Complex Figure (rec, recall; snow, Snow's correction); StroopW, Stroop number of words; StroopCE, Stroop number of errors; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (cat, number of categories; fail, failure to maintain cognitive set; firs, trials to complete first category; pers, perseverative errors).

We used generalised linear mixed-effects models to derive all test results reported here, namely tests for equality of means of diagnostic groups for demographic variables, as well as neuropsychological task scores and also the tests of association between neuropsychological test scores and STA. These models are complex because data from family members are dependent and require special methods to obtain valid significance tests. We therefore had to adjust our models by including family membership as a random effect, to control for the fact that some participants were related to one another. Not doing so can result in spuriously strong measures of association because related persons might obtain similar values owing to their shared genetic and environmental background. We also adjusted the models for some or all of the following variables (as fixed covariates): age, gender, total CTQ score, antipsychotic medication use, SCID-defined alcohol misuse or dependence, and self-rated depression scores as measured by the BDI.

Generalised linear models enable one to model variables with different distributions, and therefore one does not need to assume underlying normality for all variables used. The transformed continuous variables were modelled as normal (Gaussian) distributions. The binomial distribution was used for variables with a built-in maximum score: Stroop errors, WCST number of categories and WCST failure to maintain cognitive set. We used the Poisson distribution to model the number of hospitalisations.

A separate model was used to compare each variable (demographic and neuropsychological) simultaneously between the three diagnostic groups. For the neuropsychological variables, a second model was used to test their association with STA. Each model provides an estimate, standard error and probability value for the association between the modelled variable or score and each of the variables included in the model. The estimates and all other statistics are adjusted for each other. Because estimates of effects and their standard errors based on quantile-normalised variables (as well as those based on the binomial distribution) cannot be meaningfully interpreted, only the directions of the effects are given, not the estimates. Similarly, the complexity of these models means that statistics (global probability values) for the simultaneous testing of the three diagnostic groups are not provided.

Results

Demographic and clinical data

Demographic and clinical data are summarised in Table 1. At the time of testing, patients with a history of psychosis (bipolar(+P) group) and to a lesser extent the patients without such history (bipolar(–P) group) were, on average, significantly more depressed than their unaffected relatives (P=0.0001 and P=0.0072 respectively). The mood states as assessed with the BDI and ASRM across the groups are shown in Table 2. The bipolar(+P) group reported more childhood trauma, including sexual abuse, than both the bipolar(–P) group (P=0.0062) and unaffected individuals (P=0.0014). They also scored higher on self-reported schizotypy than both the bipolar(–P) group (P=0.0400) and unaffected relatives (P=0.001). Participants in the bipolar(+P) group were also more likely than healthy controls to have a history of alcohol misuse or dependence (P=0.0117).

Table 1 Demographic and psychometric differences across the groups (tests adjusted for family relatedness)

| Bipolar(+P) (n=25) | Bipolar(–P) (n=24) | Unaffected (n=61) | P | Summary of significant difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 45.2 (13.4) | 50.8 (16.3) | 50.7 (18.9) | 0.3718 | |

| Age at onset, years: mean (s.d.) | 24.3 (8.5) | 30.2 (13.7) | 0.1469 a | ||

| Gender, male: n (%) | 11 (44) | 14 (58) | 33 (54) | NA b | |

| WAIS general knowledge score: mean (s.d.) | 11.0 (1.4) | 11.5 (1.5) | 11.1 (1.7) | 0.6263 a | |

| Education, years: mean (s.d.) | 14.4 (2.4) | 16.2 (3.5) | 15.6 (3.7) | 0.2591 | |

| Medication, n (%) | |||||

| Antipsychotic | 5 (20.0) | 7 (29.2) | 0 (0.0) | NA b | Bipolar(–P)>bipolar(+P) (P=0.0317); bipolar(+P)>unaffected (P<0.0001); Bipolar(–P)>unaffected (P<0.0001) |

| Antidepressant | 13 (52) | 11 (46) | 2 (3) | NA b | Bipolar(+P)>unaffected (P=0.0001); bipolar(–P)>unaffected (P<0.0003) |

| Lithium | 7 (28) | 11 (45) | 0 (0.0) | NA b | Bipolar(+P)>unaffected (P<0.0001); bipolar(–P)>unaffected (P<0.0001) |

| Mood stabiliser | 15 (60) | 6 (25) | 0 (0.0) | NA b | Bipolar(+P)>unaffected (P<0.0001); bipolar(–P)>unaffected (P<0.0001) |

| Alcohol misuse/dependence, n (%) | 6 (24) | 3 (13) | 0 (0) | NA b | Bipolar(+P)>unaffected (P<0.0117) |

| Hospitalisations for depression, n: mean (s.d.) | 1.8 (2.2) | 1.7 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | NA c | |

| Hospitalisations for mania, n: mean (s.d.) | 4.2 (4.9) | 2.3 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | NA c | |

| Psychometric scores, mean (s.d.) | |||||

| Depression (BDI) | 11.3 (9.3) | 8.7 (10.6) | 4.4 (4.1) | <0.0001 | Bipolar(+P)>unaffected (P=0.0001); bipolar(–P)>unaffected (P=0.0072) |

| Hypomania (ASRM) | 3.2 (3.0) | 3.7 (4.2) | 2.5 (2.6) | 0.2411 | |

| CTQ sexual abuse | 11.3 (6.9) | 7.0 (4.0) | 6.9 (3.7) | 0.0038 a | Bipolar(+P)>bipolar(–P) (P=0.0062); bipolar(+P)>unaffected (P=0.0014) |

| CTQ total abuse | 48.8 (20.2) | 44.4 (18.5) | 36.3 (9.3) | 0.0288 a | Bipolar(+P)>unaffected (P=0.0123) |

| Schizotypy (STA) | 15.2 (6.7) | 11.9 (8.8) | 7.4 (4.7) | 0.0020 a | Bipolar(+P)>unaffected (P=0.0001); bipolar(+P)>bipolar(–P) (P=0.0400) |

ASRM, Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; bipolar(+P), bipolar disorder with positive history of psychosis; bipolar(–P), bipolar disorder with no history of psychosis; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; NA, not available; STA, Schizotypal Personality Scale; WAIS, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale

Table 2 Mood state of sample at time of testing

| Mood state | Bipolar(+P) n (%) | Bipolar(–P) n (%) | Unaffected relatives n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Euthymic | 11 (44) | 16 (67) | 51 (84) |

| Mildly depressed | 9 (36) | 6 (25) | 2 (3) |

| Moderately depressed | 4 (16) | 1 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Severely depressed | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Hypomanic | 8 (32) | 8 (33) | 7 (11) |

Bipolar(+P), bipolar disorder with positive history of psychosis; bipolar(–P), bipolar disorder with no history of psychosis

a. Transformed variable tested

b. Dichotomous (binomial) variable tested, so global P-value not available

c. Poisson counts tested, so global P-value not available

The observed differences between the study groups on chronological age, age at onset, gender ratio, SA–WAIS general knowledge scores, years of education and self-reported hypomania were not significant. There was, however, a significant difference between the two bipolar disorder groups in the numbers of people taking antipsychotic medication (P=0.0317), but not any other class of medication.

Neuropsychological data

Table 3 shows the median and range of the neuropsychological task scores in the three groups. Figure 1 shows the means across diagnostic groups of the unadjusted, transformed, neuropsychological task scores. These scores provide an indication of the relative effect sizes in the form of standard deviations from the mean. However, these are unadjusted scores; standard errors are therefore not shown on the graph since these error bars would not correspond to differences between the covariate-adjusted means.

Table 3 Neuropsychological task performance scores across the groups

| Bipolar(+P) | Bipolar(–P) | Unaffected relatives | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | ||||

| Digit Span | |||||||||

| Forward | 8 | 5–13 | 10 | 6–13 | 10 | 4–14 | |||

| Reverse | 5 | 3–10 | 6 | 3–12 | 7 | 2–12 | |||

| COWAT | 36 | 14–57 | 39 | 9–62 | 39 | 20–67 | |||

| Rey Complex Figure | |||||||||

| Recall | 20 | 4–31 | 19 | 8–34 | 24 | 4–35 | |||

| Snow's correction | 56 | 11–100 | 52 | 24–94 | 69 | 10–97 | |||

| RAVLT | |||||||||

| Learning rate a | 4 | 0–8 | 5 | 1–9 | 6 | 1–11 | |||

| Total recall | 47 | 20–66 | 43 | 15–65 | 49 | 25–69 | |||

| Recognition | 10 | 0–15 | 8 | 3–15 | 11 | 1–15 | |||

| Stroop task | |||||||||

| Number of words | 95 | 50–112 | 89 | 42–112 | 104 | 44–112 | |||

| Errors | 1 | 0–8 | 2 | 0–7 | 2 | 0–8 | |||

| WCST | |||||||||

| Number of categories | 3 | 0–5 | 4 | 0–5 | 3 | 0–5 | |||

| Trials to complete first category | 12 | 11–64 | 11 | 11–64 | 11 | 10–64 | |||

| Perseverative errors | 14 | 2–75 | 9 | 5–86 | 9 | 0–45 | |||

| Failure to maintain cognitive set | 0 | 0–2 | 0 | 0–3 | 0 | 0–3 | |||

Bipolar(+P), bipolar disorder with positive history of psychosis; bipolar(–P), bipolar disorder with no history of psychosis; COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; RAVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

a. Trial 5 minus trial 1

Table 4 contains the probability values for pairwise tests of equality in neuropsychological task performance across the groups. These tests were adjusted for age, gender, BDI score, CTQ total abuse score, antipsychotic medication, alcohol misuse/dependence, other pairwise comparisons and family relatedness. Where a significant difference was found, the direction of the effect is shown. Because these tests were applied to transformed scores, the effect sizes (and their standard errors) cannot be interpreted meaningfully and are therefore not given.

Table 4 Probability values of individual pairwise adjusted tests for differences in neuropsychological task performance scores across the groups a

| Bipolar(+P) v. bipolar(–P) | Bipolar(+P) v. unaffected | Bipolar(–P) v. unaffected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | P | P | Nature of significant difference | |

| Digit Span | ||||

| Forward | 0.1087 | 0.1345 | 0.8748 | |

| Reverse | 0.1608 | 0.0066 ** | 0.1307 | Bipolar(+P)<unaffected |

| COWAT | 0.9547 | 0.6142 | 0.6296 | |

| Rey Complex Figure | ||||

| Recall | 0.6605 | 0.1342 | 0.2528 | |

| Snow's correction | 0.6735 | 0.5757 | 0.3418 | |

| RAVLT | ||||

| Learning rate | 0.2004 | 0.0025 ** | 0.0383 * | Both bipolar(+P) and bipolar(–P) <unaffected |

| Total recall | 0.2683 | 0.0132 * | 0.1084 | Bipolar(+P)<unaffected |

| Recognition | 0.2875 | 0.0195 * | 0.1543 | Bipolar(+P)<unaffected |

| Stroop task | ||||

| Number of words | 0.5464 | 0.4466 | 0.1202 | |

| Errors | 0.1250 | 0.0350 * | 0.4213 | Bipolar(+P)<unaffected |

| WCST | ||||

| Number of categories | 0.0951 | 0.5387 | 0.2243 | |

| Trials to complete first category | 0.8717 | 0.7622 | 0.8851 | |

| Perseverative errors | 0.2649 | 0.0327 * | 0.2718 | Bipolar(+P)<unaffected |

| Failure to maintain cognitive set | 0.9172 | 0.3373 | 0.2888 |

Bipolar(+P), bipolar disorder with positive history of psychosis; bipolar(–P), bipolar disorder with no history of psychosis; COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; RAVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

a. Tests adjusted for age, gender, Beck Depression Inventory score, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire total abuse score, antipsychotic medication, alcohol misuse, other pairwise comparisons and family relatedness

* P<0.05

** P<0.01

There was no statistically significant difference between the three study groups on Digit Span forward, visual memory (RCF) and verbal fluency (COWAT). The bipolar(+P) group performed significantly worse than their unaffected relatives on the RAVLT learning rate (P=0.0025), total recall (P=0.0132) and recognition sub-tests (P=0.0195) and on the perseverative score sub-scale of the WCST (P=0.0327), as well as the reverse Digit Span (P=0.0066). The bipolar(–P) group only differed significantly from unaffected relatives on the learning rate sub-test of the RAVLT (P=0.0383). Although the bipolar(–P) group performed better than the bipolar(+P) group, the difference did not reach statistical significance for any of the neuropsychological measures (Table 4). The bipolar(+P) group made fewer errors on the Stroop task than their unaffected counterparts (P=0.0350) but did not differ significantly from the bipolar(–P) group (P=0.1250) (Table 4).

Schizotypal personality traits and cognitive performance

After adjusting for the covariates age, gender, alcohol misuse/dependence and BDI score, we found a significant negative association between STA scores and reverse Digit Span (P=0.0375), as well as RAVLT learning rate (P=0.0307). A trend towards significance (negative association) was seen with respect to the number of colour words obtained on the Stroop task (P=0.0647). There was also a significant positive association between STA scores and visual memory as measured by the RCF (P=0.0218) (Table 5).

Table 5 Probability values for test of association between schizotypal personality traits and neuropsychological task performance

| Task | P a | P b | Direction of association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digit Span | |||

| Forward | 0.2586 | 0.3149 | |

| Reverse | 0.0375 * | 0.0468 * | Negative |

| COWAT | 0.4605 | 0.5086 | |

| Rey Complex Figure | |||

| Recall | 0.0218 * | 0.0125 * | Positive |

| Snow's correction | 0.0781 | 0.0386 * | Positive |

| RAVLT | |||

| Learning rate | 0.0307 * | 0.0576 | Negative |

| Total recall | 0.3257 | 0.1608 | |

| Recognition | 0.6636 | 0.4494 | |

| Stroop task | |||

| Number of words | 0.0647 | 0.1181 | |

| Errors | 0.7809 | 0.6563 | |

| WCST | |||

| Number of categories | 0.8462 | 0.9657 | |

| Trials to complete first category | 0.7547 | 0.9829 | |

| Perseverative errors | 0.0935 | 0.0805 | |

| Failure to maintain cognitive set | 0.8615 | 0.9240 |

COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; RAVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; WCST, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test

a. Adjusted for age, gender, Beck Depression Inventory score, alcohol misuse/dependence and family relatedness

b. Additionally adjusted for antipsychotic medication use and Childhood Trauma Questionnaire total abuse score

* P<0.05

After adjusting for the previously mentioned covariates, as well as total CTQ score and antipsychotic medication use, the negative association between STA scores and the reverse Digit Span score still held (P=0.0468) and the observed negative relationship between the RAVLT learning rate and STA scores showed a trend towards significance (P=0.0576). Once again there was a significant positive relationship between STA scores and visual memory as evinced by the RCF test.

Discussion

Demographic and clinical data

The trend towards a younger age at onset of bipolar disorder in the group with a history of psychosis compared with the group without such a history (mean 24.3 years v. 30.2 years) is congruent with much of the published research. Reference Yildiz and Sachs23 The literature also notes an association between exposure to childhood abuse and an earlier age at illness onset. Reference Mann, Bortinger, Oquendo, Currier, Li and Brent24 In line with these data, our bipolar(+P) group had higher levels of self-reported childhood trauma, including sexual abuse, than the bipolar(–P) group and unaffected counterparts. This result adds to a growing literature detailing the relationship between childhood abuse and vulnerability to the development of psychotic features (reviewed by Read et al Reference Read, van Os, Morrison and Ross25 ). Most of this work has focused on psychosis in the context of schizophrenia. In one of the few exceptions, Neria et al reported that 40% of those in their first-admission psychotic bipolar disorder sample had been physically assaulted in the past, Reference Neria, Bromet, Carlson and Naz26 and patients with bipolar disorder who were exposed to childhood sexual abuse were more likely to present with hallucinations than their non-abused counterparts. Reference Hammersley, Dias, Todd, Bowen-Jones, Reilly and Bentall27 Given our results, we suggest that greater scrutiny of the role of childhood abuse in the development of bipolar disorder with psychotic features is warranted in future studies.

Startup found an association between self-reported exposure to childhood abuse and schizotypy as measured by the Oxford–Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences in volunteers from a psychology department. Reference Startup28 A similar association between schizotypal personality disorder and early maltreatment, especially neglect, has been noted. Reference Berenbaum, Valera and Kerns29 In our study, those in the bipolar(+P) group not only reported more abuse, but displayed higher levels of schizotypal personality traits compared with the bipolar(–P) group (P=0.0400). We are aware of three studies that have addressed the issue of schizotypal personality traits in bipolar disorder. Rossi et al noted levels of self-reported schizotypal personality traits in a clinically stabilised, manic bipolar disorder sample that were similar to those in a sample of patients with schizophrenia, and higher than those of healthy controls. Reference Rossi and Daneluzzo8 Heron et al found that a euthymic bipolar disorder cohort scored midway between a schizophrenia cohort and a background control group on the King's Schizotypy Questionnaire, but patients with bipolar disorder with and without a history of psychotic features did not differ on the questionnaire. Reference Heron, Jones, Williams, Owen, Craddock and Jones9 On the other hand, Schurhoff et al assessed schizotypal traits in first-degree relatives of probands with schizophrenia, psychotic bipolar disorder and non-psychotic bipolar disorder: the schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder relative groups did not differ on the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SPQ), but the relatives of psychotic bipolar disorder probands scored significantly higher on the disorganisation sub-scale of the SPQ than the non-psychotic relative group. Reference Schurhoff, Laguerre, Szoke, Meary and Leboyer10

These data are also partially consistent with family studies, which have demonstrated that the rates of schizotypal traits in relatives of patients with psychotic bipolar disorder, but not non-psychotic bipolar disorder, approximate those found in relatives of people with schizophrenia. Reference Squires-Wheeler, Skodol, Bassett and Erlenmeyer-Kimling30 Similarly, a longitudinal study reported that 35% of those scoring highly on a self-report measure of schizotypal personality traits developed various affective disorders, including bipolar disorder, after a 10-year hiatus. Reference Chapman, Chapman, Kwapil, Eckblad and Zinser31

The greater usage of antipsychotics in our bipolar(–P) group probably reflects the broadening scope of conditions other than psychosis for which these drugs appear to be useful. Various types of antipsychotic medication have shown promise as mood stabilisers or antidepressants in bipolar disorder. Reference Cousins and Young32 Congruent with this phenomenon, neither the Glahn et al nor the Bora et al samples were characterised by an excess of antipsychotic use among patients with bipolar disorder and a history of psychosis. Reference Glahn, Bearden, Barguil, Barrett, Reichenberg and Bowden11,Reference Bora, Vahip, Akdeniz, Gonul, Eryavuz and Ogut12

Neuropsychological findings

Working memory

We are aware of at least five studies that have reported deficiencies in digit span performance in people with remitted bipolar disorder. Reference Savitz, Solms and Ramesar1,Reference Robinson, Thompson, Gallagher, Goswami, Young and Ferrier2 Further, Ferrier et al noted impaired reverse digit span, as well as spatial span, as measured by the Cambridge Automated Test Battery (CANTAB), in first-degree relatives of patients with bipolar disorder. Reference Ferrier, Chowdhury, Thompson, Watson and Young33 Our finding of significantly poorer verbal working memory performance in the bipolar(+P) group is potentially important given the salience of this problem in schizophrenia. Comprehensive literature reviews and meta-analyses have noted that working memory dysfunction is a core feature of schizophrenia. Reference Bowie and Harvey34,Reference Lee and Park35 A recent meta-analysis has also suggested that the deficit extends to first-degree relatives of people with schizophrenia. Reference Trandafir, Meary, Schurhoff, Leboyer and Szoke36 In fact, Mitropolou et al have argued that working memory impairment is the key cognitive deficit in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Reference Mitropoulou, Harvey, Zegarelli, New, Silverman and Siever37 On the basis of the schizophrenia literature, and our results showing the Digit Span test to most clearly differentiate the bipolar(+P) group from the bipolar(–P) and control groups (Fig. 1), it seems a reasonable hypothesis that a disruption in working memory performance may be peculiar to, or at least more salient in, bipolar disorder cases with a history of psychotic features.

One difficulty with our hypothesis lies in the fact that patients with type II bipolar disorder, who rarely have a history of psychotic features, have also been reported to have working memory impairments as measured by reverse Digit Span. Reference Torrent, Martínez-Arán, Daban, Sánchez-Moreno, Comes and Goikolea38 Nevertheless, the sample in question might have been unusual in that approximately 20% of participants had a history of psychotic symptoms. Moreover, the sample also showed forward Digit Span performance deficits, raising the possibility that their working memory impairment was secondary to a phonological loop dysfunction. Of note is the study by Taylor Tavares et al which reported no significant spatial working memory impairment associated with type II bipolar disorder. Reference Taylor Tavares, Clark, Cannon, Erickson, Drevets and Sahakian39

Verbal memory

The significantly poorer performance of both bipolar disorder groups on the learning rate sub-test of the RAVLT (P=0.025 and P=0.0383) is consistent with much of the literature. Reference Savitz, Solms and Ramesar1,Reference Robinson, Thompson, Gallagher, Goswami, Young and Ferrier2,Reference Robinson and Ferrier40 The greater impairment in performance among the bipolar(+P) group, who also performed less well than healthy relatives on the total recall scale of the RAVLT (P=0.0132), is also consistent with the sparse literature on the topic.

Martinez-Aran et al found that patients with remitted bipolar disorder and a history of psychosis performed worse than healthy controls on the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT), Reference Martinez-Aran, Vieta, Reinares, Colom, Torrent and Sanchez-Moreno41 but the impact of antipsychotic medication on performance in this sample is a matter of debate. A follow-up study by the same group (n=35 and n=30 respectively) again emphasised the association between a history of psychotic features and verbal memory impairment. Reference Martinez-Aran, Torrent, Tabares-Seisdedos, Salamero, Daban and Balanza-Martinez42 On the other hand, the euthymic bipolar disorder sample of Kieseppa et al displayed CVLT-defined verbal learning and memory deficits compared with healthy controls, Reference Kieseppa, Tuulio-Henriksson, Haukka, Van Erp, Glahn and Cannon43 but fractionating the sample into patients with (n=20) or without (n=6) a history of psychotic features did not yield significant differences between the two bipolar disorder subgroups.

Bora et al administered various tests of executive and memory function, including the RAVLT. Reference Bora, Vahip, Akdeniz, Gonul, Eryavuz and Ogut12 Participants with bipolar disorder who had a history of psychosis (n=40) performed worse than controls on the recall sub-tests of the RAVLT, but did not differ significantly from their counterparts with no history of psychosis (n=25). Although Glahn et al did not report significant verbal memory performance differences between their two groups, Reference Glahn, Bearden, Barguil, Barrett, Reichenberg and Bowden11 approximately half of the sample were ill at the time of testing and it is unclear how this affected the results of their study.

Cognitive control

Impaired performance on the Stroop task, a measure of cognitive control (the ability to suppress prepotent responses to stimuli), has been reported in individuals with bipolar disorder in remission (e.g. Martinez-Aran et al Reference Martinez-Aran, Vieta, Reinares, Colom, Torrent and Sanchez-Moreno41 and Ali et al Reference Ali, Denicoff, Altshuler, Hauser, Li and Conrad44 ). This Stroop-induced executive dysfunction has also been reported to extend to the unaffected relatives of bipolar disorder probands, Reference Zalla, Joyce, Szoke, Schurhoff, Pillon and Komano45 and we recently observed an increase in Stroop errors in people with major depressive disorder who were members of an extended pedigree with bipolar-spectrum illness. Reference Savitz, van der Merwe, Solms and Ramesar46 In light of these data, our finding that the bipolar(+P) group actually made fewer errors than healthy relatives on the Stroop task seems unlikely to be genuine unless it is reflective of a compensatory strategy on the part of the bipolar(+P) group (i.e. reading the words more slowly).

Cognitive flexibility

The greater number of perseverative errors made on the WCST by our bipolar(+P) group compared with the healthy relative group is consistent with the finding of Bora et al that patients with a history of psychosis obtained fewer categories on the WCST than patients with bipolar disorder but no psychosis. Reference Bora, Vahip, Akdeniz, Gonul, Eryavuz and Ogut12 It is also congruent with studies noting a greater number of WCST perseverative errors in adults with schizotypal personality disorder, Reference Diforio, Walker and Kestler47 as well as in the adolescent offspring of people with schizophrenia compared with healthy controls. Reference Diwadkar, Montrose, Dworakowski, Sweeney and Keshavan48 Perseveration can be regarded as a so-called ‘bias against disconfirmatory evidence’, a trait reportedly indicative of vulnerability to schizophrenia. Reference Buchy, Woodward and Liotti49 This trait has been reported to be salient in a non-clinical sample with high scores on the SPQ. Reference Buchy, Woodward and Liotti49

Schizotypal personality traits and neurocognitive function

A methodological weakness of previous studies has been the exclusive reliance on DSM–IV criteria. As Glahn et al noted, Reference Glahn, Bearden, Barguil, Barrett, Reichenberg and Bowden11 an alternative, quantitative method of modelling psychotic features may be a better method of testing cognition–psychosis relationships than the traditional ‘yea or nay’ method of labelling people based on the SCID–I. Obtaining a valid quantitative measure of a history of psychotic features is difficult, however, and essentially suffers from the same weakness as a dichotomous retrospective diagnosis of a history of psychosis. We therefore also made use of an alternative approach, namely quantifying the level of schizotypal personality traits in our sample. Schizotypal personality traits theoretically reflect an individual's vulnerability to psychotic breakdown and by extension a genetic liability to schizophrenia. Reference Kendler and Walsh50 These personality characteristics have been shown to cluster in the unaffected relatives of patients with schizophrenia in one study, Reference Appels, Sitskoorn, Vollema and Kahn51 together with cognitive impairment. Reference Nuechterlein, Asarnow, Subotnik, Fogelson, Payne and Kendler52 Further, pre-emptive treatment of these vulnerable population groups with antipsychotic medication has met with some success. Reference McGorry, Yung and Phillips53

Working memory

The significant negative association between scores on the STA and performance on the reverse Digit Span complements our finding that the DSM–IV-defined bipolar(+P) group, but not the bipolar(–P) group, performed significantly more poorly than unaffected relatives on the Digit Span task (P=0.0066 and P=0.1608 respectively). It is also consistent with neuropsychological studies of high-risk populations displaying schizotypal personality traits.

Working memory impairment as measured by digit span, Reference Squires-Wheeler, Friedman, Amminger, Skodol, Looser-Ott and Roberts54 the delayed alternation task, Reference Dickey, McCarley, Xu, Seidman, Voglmaier and Niznikiewicz55 the dot task, Reference Roitman, Cornblatt, Bergman, Obuchowski, Mitropoulou and Keefe56 the paced auditory serial attention test Reference Mitropoulou, Harvey, Zegarelli, New, Silverman and Siever37 and a test of visual working memory, Reference Farmer, O'Donnell, Niznikiewicz, Voglmaier, McCarley and Shenton57 has been reported in patients with schizotypal personality disorder. In fact, spatial working memory impairment has been reported to constitute an endophenotypic marker for vulnerability to psychotic breakdown. Reference Wood, Pantelis, Proffitt, Phillips, Stuart and Buchanan58 Congruent with these data, self-report measures of schizotypal personality traits have also been shown to predict working memory performance. Performance on a spatial working memory task was found by Park et al to be more impaired in people who scored higher on the Perceptual Aberration Scale Reference Park, Holzman and Goldman-Rakic5 and a follow-up study replicated this effect with the SPQ. Reference Park and McTigue59 More recently, Kopp noted a deficit in the executive control of working memory in participants scoring highly on the SPQ. Reference Kopp60

Visual memory

Visual memory dysfunction per se is not generally regarded as a particularly salient feature of the schizotypal personality disorder cognitive profile, Reference Myles-Worsley, Ord, Ngiralmau, Weaver, Blailes and Farone61 although some studies have certainly noted impairments. Reference Savitz, Solms and Ramesar1,Reference Robinson, Thompson, Gallagher, Goswami, Young and Ferrier2 Nevertheless, the positive association between STA scores and RCF performance in our sample is counter-intuitive and is not supported by the literature. We raise the possibility that this is a false positive result.

Verbal declarative memory

The negative association between STA scores and scores obtained on the learning rate sub-test of the RAVLT is consistent with a meta-analysis of 20 studies examining verbal memory function in first-degree relatives of people with schizophrenia, which reported impairment in verbal declarative memory with a small to moderate effect size. Reference Whyte, McIntosh, Johnstone and Lawrie62

In conclusion, we find no evidence that ‘psychotic’ and ‘non-psychotic’ subtypes of bipolar disorder are qualitatively different from each other in terms of their cognitive function. Nevertheless, the two putative subtypes of bipolar disorder appear to be quantitatively different, suggesting that they may lie on a nosological continuum most clearly defined by degree of verbal working and declarative memory impairment.

Strengths of the study

In this study we used three original strategies.

-

(a) Schizotypal personality traits, which are postulated to be indicative of a vulnerability to psychotic breakdown, were used as a quantitative predictor of neurocognitive function. Thus, we obtained convergent results with two different measures of the psychotic bipolar disorder ‘subtype’.

-

(b) Childhood trauma, which is associated with psychotic symptoms and cognitive dysfunction, was measured and controlled for, possibly improving the accuracy of our results compared with previous studies.

-

(c) Our family-based design not only makes it more likely that our three comparison groups came from similar cultural and socio-economic backgrounds, but also may have decreased genetic heterogeneity across the sample.

Limitations

It would have been useful to have recruited a comparison group of people with schizophrenia to compare with our bipolar(+P) group. Similarly, our two bipolar disorder groups might have differed more sharply from a group of unrelated healthy controls than from their unaffected relatives. Second, given the evidence for working memory deficits in schizophrenia and in bipolar disorder with a history of psychosis, our study would have benefited from a more thorough interrogation of working memory. For example, a test of visual working memory would have strengthened our conclusions. Third, we made use of only one measure of schizotypal personality traits – the STA. Schizotypy encompasses a heterogeneous collection of traits and the STA does not differentiate between positive, negative and disorganised aspects of schizotypy. It is, therefore, conceivable that different results would have been obtained using another questionnaire.

Although our sample size compares favourably with those in other studies, Reference Glahn, Bearden, Barguil, Barrett, Reichenberg and Bowden11,Reference Bora, Vahip, Akdeniz, Gonul, Eryavuz and Ogut12,Reference Martinez-Aran, Vieta, Reinares, Colom, Torrent and Sanchez-Moreno41,Reference Selva, Salazar, Balanza-Martinez, Martinez-Aran, Rubio and Daban63 it is conceivable that a larger sample size would have further differentiated the psychosis from the non-psychosis groups. Other limitations are that psychosis may not be a unitary construct – in other words, heterogeneous patterns of psychotic symptoms may differentially affect neurocognition and course of illness. No follow-up SCID–I interviews were carried out after the initial wave of the study and, thus, the possibility exists that some of the participants' diagnoses would have changed in the intervening period. Finally, our sample was selected for a genetic loading towards bipolar disorder and therefore our results may not be generalisable to sporadic populations.

Future work

Given the difficulty of comprehensively controlling for confounding variables in cross-sectional analyses, well-controlled prospective studies that follow at-risk individuals prior to the onset of illness are the optimal way to assess phenotypic differences between people with bipolar disorder with and without psychotic features. Another possible strategy to reduce genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity is to recruit extended families with a high density of affected individuals. An example of this approach can be seen in our earlier study. Reference Savitz, van der Merwe, Solms and Ramesar46 Ideally, a large extended family with a high density of psychotic bipolar disorder could be compared with a family with a milder, non-psychotic form of bipolar disorder.

Acknowledgements

The support of the Medical Research Council of South Africa and the University of Cape Town Brain and Behaviour Initiative is acknowledged. We thank Elize Pietersen and Gameda Benefeld for conducting psychological interviews.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.