There is growing evidence of significant impairment in neurocognitive functioning in major depressive disorder (Reference Austin, Mitchell and GoodwinAustin et al, 2001). However, findings to date have been variable (see Reference Grant, Thase and SweeneyGrant et al, 2001), with many factors potentially contributing to inconsistencies between studies, including: age; hospitalisation; severity and subtype of depression; and, most importantly, the effect of psychotropic medication. The current study sought to address these previous limitations by testing a well-characterised group of medication-free patients with major depressive disorder on a comprehensive neurocognitive test battery. We hypothesised that patients would demonstrate clear neurocognitive impairment when compared with well-matched control subjects.

METHOD

Subjects

Patients aged 18-65 years with a DSM—IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) confirmed diagnosis of major depressive disorder (single episode or recurrent) were recruited from general practice clinics in the Tyne and Wear region. Patients had been entirely psychotropic-medication-free for at least 6 weeks before recruitment and were excluded if currently taking other medication active in the central nervous system (CNS-active), including β -blockers or St John's wort, or if there was a comorbid medical/psychiatric diagnosis, or a recent history of alcohol/substance misuse. Severity of depression was assessed using the Montgomery—Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS; Reference Montgomery and ÅsbergMontgomery & Åsberg, 1979), the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD17; Reference HamiltonHamilton, 1960) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Reference Beck, Ward and MendelsonBeck et al, 1961). DSM—IV criteria for melancholia were noted and the Newcastle Scale (Reference Carney, Roth and GarsideCarney et al, 1965) completed. The Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (Reference Teng and ChuiTeng & Chui, 1987) was administered to screen for dementia.

The control group consisted of subjects who were psychologically and physically fit (verified by examination) and had no recent history of illicit drug use or alcohol misuse. Controls were excluded if they had a history of psychiatric illness (personally or in a first-degree relative) or a BDI score > 7. Current alcohol intake was less than 28 units/week for males and 21 units/week for females.

Patients and controls were matched for age, gender, premorbid IQ (National Adult Reading Test (NART); Reference NelsonNelson, 1982), years of formal education and season of testing. Females were matched for phase of menstrual cycle (see Table 1). All subjects had English as a first language. Subjects were tested as soon after recruitment as possible to minimise delay in treatment and in all cases treatment was commenced within 1 week of the initial assessment. The study was approved by the Newcastle and North Tyneside Health Authority Joint Ethics Committee and all subjects gave written informed consent.

Table 1 Demographic details for subjects with depression and for controls

| Depression | Controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | s.d. | Range | Mean | s.d. | Range | |

| Age (years) | 32.9 | 10.6 | 19-61 | 32.3 | 11.4 | 18-55 |

| NART | 107.9 | 10.7 | 85-123 | 109.6 | 7.6 | 89-122 |

| Formal education (years) | 13.3 | 2.4 | 10-16 | 14.2 | 1.7 | 11-16 |

| Gender (male:female) | 15:29 | 15:29 | ||||

| Season1 | 9:11:16:8 | 7:11:19:7 | ||||

| Menstrual cycle2 | 13:7:5 (3 unknown) | 18:8:3 | ||||

Neuropsychological testing

Subjects were tested at 14.00 h, testing taking approximately 90 min to complete. The battery was designed to assess a broad range of cognitive domains. Pen-and-paper tasks were administered according to standardised instructions (Reference LezakLezak, 1995) and computerised tests from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) according to CANTAB manual protocols, on a PC fitted with a colour touch-screen monitor. These tests are briefly summarised below; detailed descriptions are available elsewhere (Reference Owen, Sahakian and SempleOwen et al, 1995; Reference Young, Sahakian and RobbinsYoung et al, 1999).

Psychomotor performance tests

Digit Symbol Substitution Task (DSST; Reference WechslerWechsler, 1981)

Primarily a test of psychomotor speed, which involves set-shifting and selective sustained attention. Total number correct in 90s is recorded.

Learning and memory (verbal) tests

Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT; Reference ReyRey, 1964)

A test of verbal learning, including delayed recall and recognition. The numbers of words correct are recorded. As performance on the final two recall trials of List A depends upon how well the words were learned initially, these scores are calculated as a percentage of the maximum score from the first five recalls. Proactive and retroactive interference indices are also derived.

Learning and memory (visuospatial) tests

Paired-associates learning (CANTAB)

Subjects learn and then replicate the matching of two complex stimuli to specific spatial locations on the screen within ten attempts. The number of stimulus—location pairs then increases from three up to eight.

Pattern recognition (CANTAB)

Subjects learn a series of twelve complex patterns before being presented with pairs of patterns and are required to identify the familiar one. Two sets are presented.

Spatial recognition (CANTAB)

Subjects are required to learn the on-screen spatial position of five serially presented squares, with a subsequent forced-choice recognition between two locations. Four trials are completed.

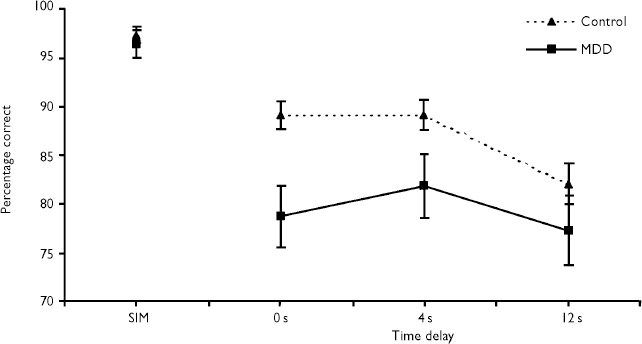

Simultaneous/delayed matching to sample (CANTAB)

Subjects must recognise a previously presented stimulus item from among four very similar stimuli after a delay of either 0, 4 or 12 s.

Sustained attention and executive function

Controlled oral word association test (Benton's FAS; Reference Benton and HamsherBenton & Hamsher, 1976)

In this verbal fluency test, subjects generate words beginning with ‘F’, ‘A’ and ‘S’, following a prescribed set of rules.

‘Exclude letter’ fluency test (ELFT; Reference Bryan, Luszcz and CrawfordBryan et al, 1997)

This verbal fluency test follows the same format as the FAS, but the words must not contain the letters ‘E’, ‘A’ or ‘I’.

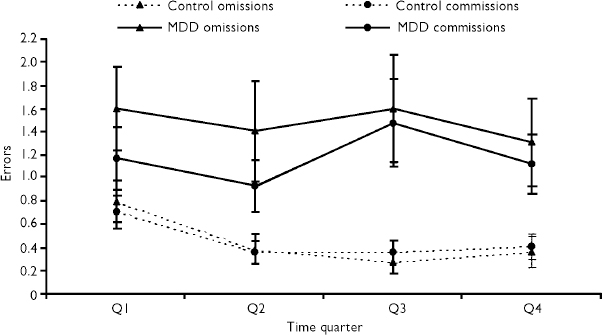

Vigil continuous performance test (Reference Cegalis and BowlinCegalis & Bowlin, 1991)

In this continuous performance test, subjects view serially presented random letters over 8 minutes and must respond only to the sequence of an ‘A’ followed by a ‘K’. Response latency and errors of omission and commission are recorded.

Spatial working memory (CANTAB)

This is a self-ordered search task that requires subjects to locate counters hidden in boxes and avoid repetitious searching of locations. An index of strategy is also generated.

Tower of London (CANTAB)

This test of planning taxes central executive function. Subjects must rearrange a set of spheres to match a given target arrangement in a specified minimum number of moves. Accuracy and latency are recorded.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and neurocognitive data were assessed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with group (depression or control) as the between-subject factor. Where tests had more than one level, an additional within-subjects factor of ‘time’ or ‘problem level’ was added and analysed by repeated-measures ANOVA, within a multivariate general linear model. Degrees of freedom were adjusted using the Huynh—Feldt epsilon if the assumption of sphericity was violated. For clarity, unadjusted degrees of freedom are reported. To reduce skewness, measures of response latency were logarithmically transformed (base 10) and errors on the spatial working memory task were square-root transformed. Where data could not be transformed, non-parametric tests were employed. Estimates of effect size were calculated for untransformed data using the formula (μMDD — μ controls)/σpooled, where MDD denotes major depressive disorder (Reference HowellHowell, 1999). Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 9 (SPSS, 1998).

RESULTS

Forty-four patients with major depressive disorder were recruited. Five fulfilled DSM—IV criteria for melancholia, whereas six met the Newcastle criteria for ‘endogenous’ depression (overall, three met criteria for both). A total of 30 patients were first-episode (68%), with 11 (25%) having had one previous depressive episode and only 3 (7%) having had 2 or more. Twenty-six patients (59%) were entirely drug-naïve; of the 18 that had previously received antidepressant medication, the average (median) drug-free duration was 48 weeks (range 6 to 336 weeks). No patient had previously received electroconvulsive therapy.

Patients were matched with a control group of 44 healthy subjects. Gender, age (F=0.07, d.f.=1,86, P=0.80), NART-estimated IQ (F=0.74, d.f.=1,86, P=0.39), years of formal education (U=779.5, P=0.10), season of testing (χ2=0.57, d.f.=3, P=0.90) and, for female subjects, phase of menstrual cycle (χ2=1.08, d.f.=2, P=0.58) did not differ between groups. Demographic details are presented in Table 1 and additional illness characteristics in Table 2. Results of the neurocognitive tests are presented in Table 3.

Table 2 Patients with depression: illness characteristics and rating scales

| Mean (median) | s.d. | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HRSD17 | 21.1 | 4.4 | 15-30 |

| MADRS | 28.9 | 5.5 | 18-38 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 27.9 | 10.2 | 8-47 |

| Total lifetime duration (months) | 17.5 (7) | 29.3 | 2-120 |

| Age at onset (years) | 29.2 | 9.0 | 17-51 |

| Length of current episode (months) | 12.5 (6) | 23.5 | 1-120 |

| Duration drug-free (weeks)1 | 78.6 (48) | 85.9 | 6-336 |

Table 3 Results of neurocognitive tests with effect sizes (see text for statistical analyses)

| Control | Depression | Effect size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | s.d. | Mean | s.d. | ||

| Psychomotor performance | |||||

| Digital Symbol Substitution Task | |||||

| Total correct | 63.6 | 11.2 | 62.2 | 9.3 | -0.14 |

| Learning and memory (verbal) | |||||

| Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test | |||||

| List 1 | 7.2 | 2.0 | 6.5 | 1.4 | -0.40 |

| Total 1-5 | 54.0 | 9.6 | 50.7 | 8.0 | -0.37 |

| List B | 6.7 | 2.1 | 5.7 | 2.1 | -0.46 |

| List 6 (%) | 83.1 | 19.6 | 79.5 | 14.3 | -0.21 |

| Retroactive inhibition | -1.6 | 2.1 | -1.9 | 1.6 | -0.18 |

| Proactive inhibition | -0.4 | 1.9 | -0.8 | 1.7 | -0.19 |

| Long-term recall/recognition | |||||

| List 7 (% recall) | 82.5 | 16.2 | 75.7 | 17.4 | -0.40 |

| List A recognition | 13.4 | 1.6 | 12.5 | 2.2 | -0.46 |

| Learning and memory (visuo-spatial) | |||||

| Paired-associates learning | |||||

| Total levels correct | 7.9 | 0.3 | 7.9 | 0.4 | -0.13 |

| First trials correct | 6.4 | 0.7 | 5.8 | 1.1 | -0.60 |

| Pattern recognition | |||||

| Total correct (%) | 89.5 | 11.1 | 82.7 | 13.8 | -0.53 |

| Latency (ms)1 | 1904 | 356 | 2220 | 579 | 0.63 |

| Spatial recognition | |||||

| Total correct (%) | 84.2 | 11.4 | 77.9 | 11.8 | -0.53 |

| Latency (ms)1 | 2038 | 695 | 2203 | 647 | 0.24 |

| Simultaneous matching to sample | |||||

| Correct (%)2 | 97.3 | 5.5 | 96.4 | 9.0 | -0.12 |

| Latency1 | 2574 | 757 | 2637 | 580 | 0.09 |

| Delayed matching to sample | |||||

| Correct (%)2 | 86.7 | 6.7 | 79.2 | 18.5 | -0.52 |

| Latency1 | 3215 | 952 | 3272 | 988 | 0.06 |

| Attention and executive function | |||||

| Benton's FAS, total correct | 44.1 | 13.6 | 38.5 | 10.9 | -0.44 |

| ‘Exclude letter’ fluency test, total correct | 49.0 | 11.5 | 41.8 | 11.1 | -0.61 |

| Vigil | |||||

| Total omissions | 1.8 | 2.6 | 5.9 | 9.7 | 0.56 |

| Total commissions | 1.9 | 1.9 | 4.7 | 6.1 | 0.60 |

| Average latency (ms)2 | 372.8 | 57.3 | 393.1 | 89.9 | 0.27 |

| Spatial working memory | |||||

| Total between-search errors1 | 23.1 | 17.1 | 36.7 | 21.5 | 0.67 |

| Strategy score1 | 32.5 | 5.8 | 36.2 | 6.1 | 0.59 |

| Tower of London task | |||||

| Perfect solution (%)2 | 72.9 | 15.0 | 75.8 | 13.3 | 0.21 |

| Number of excess moves2 | 0.94 | 0.56 | 0.86 | 0.56 | -0.15 |

| Average initial thinking time (ms)1,2 | 7247 | 4101 | 7410 | 3067 | 0.04 |

| Average subsequent thinking time (ms)1,2 | 2480 | 1128 | 2768 | 1180 | 0.25 |

Psychomotor performance tests

DSST

There was no significant difference in total correct responses between patients with depression and controls (F=0.45, d.f.=1,86, P=0.50).

Learning and memory (verbal) tests

RAVLT

There was no significant group difference in immediate word span (U=803, P=0.16) or verbal learning (F=3.07, d.f.=1,86, P=0.084). A significant learning effect was observed across successive presentations (F=274.7, d.f.=4,344, P<0.0005), but no difference in learning curves between groups (F=0.20, d.f.=4,344, P=0.92). Performance on the distractor list was poorer in patients with depression (U=661.5, P=0.009). No group difference was found on List 6 (F=0.98, d.f.=1,86, P=0.33) or delayed word recall (F=3.62, d.f.=1,86, P=0.06) or recognition (U=750, P=0.06).

Learning and memory (visuospatial) tests

Paired-associates learning

Patients with depression completed fewer trials successfully on the first presentation compared with controls (F=8.56, d.f.=1,86, P=0.004), although there was no difference in the number of levels correctly completed (F=0.35, d.f.=1,86, P=0.56).

Pattern and spatial recognition

Patients with depression were significantly less accurate on the pattern (F=6.52, d.f.=1,86, P=0.01) and spatial (F=6.43, d.f.=1,85, P=0.01) recognition tasks. Patients were also slower to respond on the former (F=9.11, d.f.=1,86, P=0.003).

Simultaneous/delayed matching to sample

Accuracy on the simultaneous trial did not differ between groups (F=0.30, d.f.=1,78, P=0.59). For delayed trials, the group with depression performed significantly worse than controls (F=5.79, d.f.=1,78, P=0.02). There was also a main effect of delay (F=7.55, d.f.=2,156, P=0.003), performance being worse at the 12-s delay (see Fig. 1). No effect of group was found on latency measures (F=0.34, d.f.=1,78, P=0.85).

Fig. 1 Percentage of correct responses for simultaneous and delayed matching to sample (mean±s.e.m.): MDD, major depressive disorder; SIM, simultaneous trial.

Sustained attention and executive function tests

Verbal fluency

Patients with depression generated fewer words on the FAS test (F=4.48, d.f.=1,86, P=0.037) and ELFT (F=8.75, d.f.=1,84, P=0.004). There was no significant correlation between the number of words generated on each of these tests for control subjects (r=0.245, R 2=0.06, P=0.11); however, a strong correlation was observed for patients with depression (r=0.671, R 2=0.45, P<0.001).

Vigil continuous performance test

Patients with depression made significantly more errors of omission (U=694.5, P=0.04) and commission (U=684.5, P=0.04) than controls. In patients, there was no change in error rate over time; however, controls made fewer errors after the first 2 minutes of the test (χ2 F=12.6, d.f.=3, P=0.005; see Fig. 2). There was no difference between groups in response latency (F=1.04, d.f.=1,84, P=0.31).

Fig. 2 Mean (untransformed) Vigil omission and commission errors across each 2-min time quarter of the test: MDD, major depressive disorder.

Spatial working memory

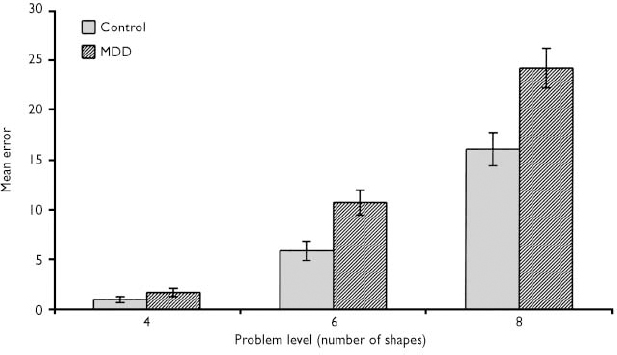

There were significant effects of group (F=8.62, d.f.=1,85, P=0.004), level (F=284.0, d.f.=2,170, P<0.0005) and a group by level interaction (F=4.49, d.f.=2,170, P=0.013) in the number of between-search errors. Patients with depression made more errors than controls at the six- (t=2.91, d.f.=85, P=0.005) and eight-shape (t=2.92, d.f.=85, P=0.004) problems (see Fig. 3). The strategy score was also greater in patients with depression, indicating a less-efficient search strategy (F=8.22, d.f.=1,85, P=0.005).

Fig. 3 Spatial working memory between search errors (mean±s.e.m.): MDD, major depressive disorder.

The correlation between strategy score and total between-search errors revealed a linear relationship between these variables in both the depression (r=0.85, R2=0.72, P<0.001) and the control groups (r=0.60, R2=0.36, P<0.001).

Tower of London

There was no main effect of group in the number of excess moves (F=0.43, d.f.=1,75, P=0.52), proportion of perfect solutions (F=0.84, d.f.=1,74, P=0.36), initial thinking time (F=1.07, d.f.=1,75, P=0.30) or subsequent thinking time (F=1.73, d.f.=1,75, P=0.19). As expected, significant effects of level were observed on all measures (P<0.0005), but no interactions were present in any measure other than initial thinking time (F=3.88, d.f.=3,225, P=0.013).

Exploratory data analyses

Correlations between severity of depression and cognitive performance

Correlations were performed between HRSD17 ratings and neurocognitive test measures in subjects with depression. Correlations attaining significance were found on indices of learning and memory: RAVLT, retroactive interference (r=-0.33, P=0.028), long-term recall (r=-0.31, P=0.043) and long-term recognition (r=-0.32, P=0.034); pattern recognition, percentage correct (r=-0.30, P=0.046); delayed matching to sample (r=-0.38, P=0.02); and paired-associates learning, total trials (r=-0.38, P=0.014).

Correlations between cortisol/DHEA ratios and cognitive performance

Correlations between neurocognitive performance and the previously reported 08.00-h and 20.00-h cortisol/dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) ratios from this group were also examined (Reference Young, Gallagher and PorterYoung et al, 2002). In control subjects there were no significant correlations. In subjects with depression, the 20.00-h cortisol/DHEA ratio correlated negatively with performance on the DSST (r s =-0.38, P=0.016) and positively with Tower of London initial thinking time (r s =0.36, P=0.032). No other significant correlations were found.

Analysis of subgroups

The primary outcome measures were reanalysed after omitting the five patients meeting DSM—IV criteria for melancholia. Small changes in the magnitude of differences emerged; however, the profile of impairment in the group with depression did not alter, with the exception of the FAS verbal fluency test and delayed matching-to-sample trials, which no longer reached statistical significance. Similarly, when the six Newcastle-defined ‘endogenous’ patients were excluded, FAS and RAVLT List B recall no longer reached significance (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates significant neurocognitive impairment in young adult out-patients with unipolar depression, compared with a well-matched control group. Patients with depression were found to be impaired across a range of cognitive domains, including attention/executive function and visuospatial learning and memory. The deficits were found almost exclusively in measures of accuracy. Only one task, pattern recognition, also showed increased response latency. These findings cannot be attributed to the concomitant administration of psychotropic or CNS-active medication, or to the effects of medication withdrawal.

Learning and memory

Verbal declarative memory as assessed by the RAVLT was preserved, with no differences between patients with depression and controls on immediate word span, learning or long-term recall and recognition. Although recall of the distractor list differed between groups, there was no evidence of proactive inhibition. Several earlier studies have shown that patients with depression were impaired particularly on tests of verbal learning and memory (e.g. Reference Austin, Mitchell and WilhelmAustin et al, 1999). However, such tasks are sensitive to the effects of some antidepressants (Reference Schmitt, Kruizinga and RiedelSchmitt et al, 2001) and the medication-free status of patients in this study could explain the discrepancy. One study examining patients who had been drug-free for 2 weeks showed no difference between patients with non-psychotic major depressive disorder and controls in verbal memory, whereas executive performance (Stroop) was impaired (Reference Schatzberg, Posener and De BattistaSchatzberg et al, 2000). Alternatively, the absence of impairment could be attributable to other factors such as the small proportion of patients with severe depression or melancholia in our sample. Austin et al (Reference Austin, Mitchell and Wilhelm1999), using Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation and Newcastle definitions of melancholia, found that pronounced deficits in verbal learning, recall and recognition were observed in patients with melancholia compared with controls, whereas performance was preserved in patients without melancholia.

In our study, recognition memory for visually presented patterns and spatial locations was impaired in the depression group, with reaction times also increased in the former. Previously, such impairments have been reported in middle-aged (Reference Elliott, Sahakian and McKayElliott et al, 1996) and elderly patients with depression (Reference Beats, Sahakian and LevyBeats et al, 1996), although deficits are observed rarely in studies of younger in-patient and out-patient populations (Reference Grant, Thase and SweeneyGrant et al, 2001).

The impairment in accuracy found on the delayed matching-to-sample task has been reported more consistently in in-patients and out-patients across all age groups (Reference Beats, Sahakian and LevyBeats et al, 1996; Reference Elliott, Sahakian and McKayElliott et al, 1996). An exception to this is the study by Grant et al (Reference Grant, Thase and Sweeney2001), in which there was a general absence of neurocognitive impairment across a broad range of tests, although on some measures subjects with depression out-performed controls, being faster (delayed matching-to-sample latency and reaction time) and more accurate (selected tests of learning/memory). This is likely to be attributable to the very mild severity of depression in their patient sample.

Attention and executive function

Some of the most robust effects in the present study were found on tests of attention and executive function. This is in accordance with the findings of many previous studies (Reference Rogers, Bradshaw and PantelisRogers et al, 1998). Patients with depression made more errors of omission and commission on the Vigil continuous performance test. These were evident in the first quarter of the test and did not increase over time, suggesting that some of the impairments found in other tests could be the result of a general reduction in attentional resources or focus. As both types of error were greater in the patient group, it is not the case that patients with depression adopted a more conservative response style.

Although there were impairments on the majority of executive tests, there was no significant difference between patients and controls on the Tower of London task. This is perhaps unsurprising, given the multiplicity of processes subserved by the central executive, alongside evidence that even ‘dysexecutive’ patients can show intact performance on some putative measures of executive function (Reference Baddeley, Delia Sala and PapagnoBaddeley et al, 1997).

Although large effect sizes were present in tests of executive function, performance did not correlate with severity of depression, whereas selected performance (accuracy) indices of most tests of learning and memory did. It is possible that executive functions are more sensitive, being affected adversely irrespective of the severity of depression. The correlation between verbal and visuospatial learning and memory, however, suggests that such functions are relatively intact in milder depressive episodes, becoming more pronounced as severity increases. Alternatively, executive deficits could represent a relatively stable trait marker, whereas mnemonic impairment is related to clinical state. Indeed, some studies have failed to demonstrate any residual memory impairment after clinical recovery, whereas others show persistent impairment, particularly in aspects of executive functioning (Reference Beats, Sahakian and LevyBeats et al, 1996; Reference Paradiso, Lamberty and GarveyParadiso et al, 1997).

Factors affecting neurocognitive performance

The patients recruited in this study were younger (<65 years) adult out-patients with a moderate severity of illness and were drug-naïve or unmedicated for a sufficient period of time up to and including the neurocognitive test day to exclude the effects of psychotropic medication as a potential confounder. The patient sample was also clinically homogeneous, with only five patients fulfilling DSM—IV criteria for melancholia, none having a comorbid medical or psychiatric diagnosis, and the majority (68%) experiencing their first depressive episode. As described previously, all these factors affect the pattern and magnitude of the observed neurocognitive deficits.

Previous studies have demonstrated deficits in neurocognitive performance in patients both with and without melancholia, generally more pronounced in the former (Reference Austin, Mitchell and WilhelmAustin et al, 1999). The impact of depressive subtype is, however, complicated by a difficulty in differentiating between the effects of severity and subtype (Reference Austin, Mitchell and WilhelmAustin et al, 1999). Psychomotor slowing has been suggested as a feature of melancholic depression. It is found more commonly in older subjects with depression (Reference Beats, Sahakian and LevyBeats et al, 1996). As the subjects with depression in our study were neither elderly, nor on the whole had melancholia, it is unsurprising that we found no evidence of motor/psychomotor retardation as indexed by reaction times and performance on the DSST.

The effects of antidepressant and other psychotropic medication and their withdrawal could be of particular importance in studies of cognitive function in samples with less-severe depression or non-melancholic depression, where impairment could be more subtle. In general it appears that antidepressants with anticholinergic properties impair aspects of cognitive function, whereas there could be less effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or monoamine oxidase inhibitors. However, a recent study suggests adverse effects of the SSRI paroxetine on verbal learning (Reference Schmitt, Kruizinga and RiedelSchmitt et al, 2001), probably related to anticholinergic effects, whereas sertraline was found to have positive effects on verbal fluency, related to dopaminergic effects. Some studies have attempted to control for antidepressant effects by using a wash-out period. Unfortunately, it could be that in some cases this has not been long enough as, although onset of antidepressant discontinuation symptoms is usually within 5 days of cessation, symptoms can last 1-3 weeks (Reference HaddadHaddad, 1998).

Current hypotheses on the nature of neurocognitive impairment in depression

To explain the cognitive impairment seen in depression, some authors have suggested that effort is the principal mediating factor, whereby reduced attentional capacity causes impairment on tasks requiring effortful processing (Reference Hasher and ZacksHasher & Zacks, 1979). There is some support for this hypothesis, although it has been argued that subjects with depression might be able to mobilise resources to complete effortful tasks unless decision-making is required (Reference Thomas, Goudemand and RousseauxThomas et al, 1999), and therefore that effort and attention are not necessarily synonymous. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated minimal effect sizes on tests of primary, semantic and working memory, with the most prominent effects being in the effortful encoding of information and an accompanying inefficiency of retrieving poorly encoded information from declarative memory (Reference Zakzanis, Leach and KaplanZakzanis et al, 1998). Our results do not support this hypothesis. Performance deficits were observed on tasks of visual and spatial recognition memory in the face of intact declarative verbal learning and memory. Recognition is assumed to be less effortful than recall; therefore, the pattern of results does not fit the profile that would be predicted from this hypothesis. It has also been argued that the neurocognitive deficits could simply be the result of reduced motivation to testing; however, again, the results do not support this. Deficits were not observed on all tests and did not become more pronounced towards the end of the test session, when it might be expected that motivation would be affected adversely. Furthermore, it has been argued that because of the relationship between affect and drive (or motivation), to study reduced motivation is, in some respects, to study depression itself (Reference Austin, Mitchell and GoodwinAustin et al, 2001).

Elevated levels of corticosteroids have been shown to impair learning and memory in humans. This has been demonstrated by acute and subchronic (Reference Young, Sahakian and RobbinsYoung et al, 1999) administration of exogenous corticosteroids in healthy volunteers and in conditions associated with a chronic elevation of endogenous cortisol levels, for example Cushing's disease (Reference Starkman, Giordani and BerentStarkman et al, 2001). Hypercortisolaemia, which is frequently described in major depressive disorder, has therefore been suggested to be one of the principal causes of neurocognitive impairment. In earlier work (Reference Young, Gallagher and PorterYoung et al, 2002), we found evidence of an elevation in cortisol/DHEA ratios in the patients with depression, which provides a more accurate estimate of ‘functional’ hypercortisolaemia, although no correlation was found with neurocognitive test performance in general. Work has suggested that optimum neurocognitive functioning may be dependent upon the relative occupancy of mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors in the brain (Reference de Kloet, Oitzl and Joelsde Kloet et al, 1999). Therefore, although measures could reveal state-related increases in hypothalamic—pituitary—adrenal axis activity, they do not assess more-subtle facets of dysfunction at the receptor level, such as glucocorticoid receptor-mediated negative feedback mechanisms. For this, moresensitive ‘activated’ tests such as the dexamethasone/corticotropin releasing hormone challenge could be required.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Patients with major depressive disorder show pronounced impairment in executive function, with additional effects on mnemonic function dependent upon severity of depression.

-

▪ The neurocognitive impairment was found in a group of young, predominantly first-episode, out-patients without melancholia and was not because of the effects of psychotropic medication.

-

▪ Neurocognitive impairment is an objective measure that may be used as a tool to investigate the abnormalities in brain function underlying major depressive disorder.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ The patients studied were predominantly not severely depressed.

-

▪ The specific cognitive architecture or neural basis of the impairment was not fully demonstrated.

-

▪ The temporal trajectory of impairment, in particular, the degree of recovery with symptom resolution, remains to be fully determined.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.