Lack of insight in psychiatric illness may comprise multiple processes such as self-awareness, attribution of illness, social consequences of illness and perceived need for treatment (Reference DavidDavid, 1990; Reference Amador, Flaum and AndreasenAmador et al, 1994; Reference Morgan, David, Amador and DavidMorgan & David, 2004), some of which may be amenable to treatment. However, poor insight may result from cognitive impairment (for review, see Reference Aleman, Agrawal and MorganAleman et al, 2006). If lack of insight is underpinned by cognitive impairment, then it may require a therapeutic approach which is different from that currently offered (Reference Henry and GhaemiHenry & Ghaemi, 2004). Flashman & Roth (Reference Flashman, Roth, Amador and David2004) proposed a classification of insight that divided patients into three groups: those with full insight (aware, correct attributers); those aware of being unwell, but who misattributed their symptoms (aware, incorrect attributers); and those unaware of being ill (unaware). These authors suggested that unawareness of illness was caused by brain dysfunction. If true, this implies that the aware, misattributing group might be cognitively intact, and therefore might be helped by psychoeducation or psychotherapy. We predicted that cluster analysis would yield three groups that would be consistent with this model. In addition, we tested the hypothesis that unawareness would be associated with cognitive impairment, whereas cognitive function would be intact in those who misattributed illness.

METHOD

We recruited 56 patients with DSM–IV schizophrenia (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). This sample comprised 51 men and 5 women (mean age 35.0 years, s.d.=10.0; mean duration of illness 10.5 years, s.d.=8.5; mean years of education 12.2 years, s.d.=2.5). Their mean score on the Schedule for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (Reference AndreasenAndreasen, 1983) was 8.1 (s.d.=3.9) and on the Schedule for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (Reference AndreasenAndreasen, 1984) it was 7.0 (s.d.=4.5). Mean IQ from the National Adult Reading Test (Reference NelsonNelson, 1991) was 105.4 (s.d.=11.7). All but five patients were taking antipsychotic medication.

Assessment

Insight was assessed using the Schedule for the Assessment of Insight (SAI; Reference DavidDavid, 1990), a semi-structured interview assessing three dimensions of insight (treatment adherence, awareness of illness and relabelling of psychotic phenomena). The 64-card version of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST; Reference Kongs, Thompson and IversonKongs et al, 2000) was used to measure executive function and the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised (HVLT–R; Reference Brandt and BenedictBrandt & Benedict, 2001) was used as an index of working memory.

Data analyses

An agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward's method (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, release 12 for Windows) was used to classify participants into three groups, based on SAI sub-scores for awareness of illness and relabelling of symptoms. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the three groups on WCST perseverative errors and HVLT–R total score. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 (two-tailed).

RESULTS

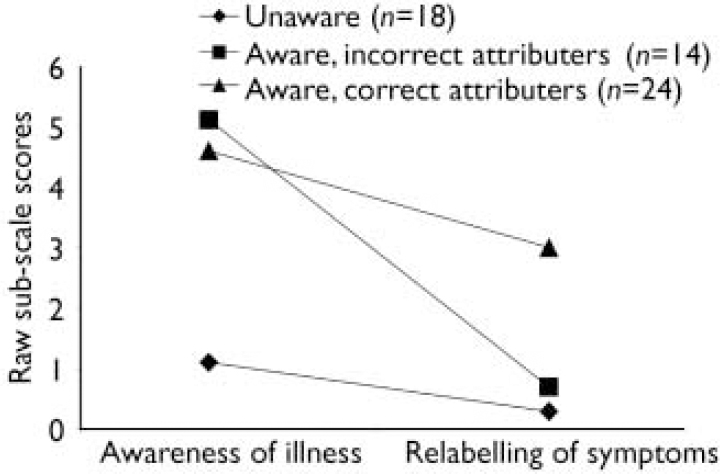

One-way ANOVAs showed that the three groups were not significantly different in terms of age, years of education, duration of illness or NART IQ. The three clusters are shown in Fig. 1. The ‘unaware’ group (n=18) had low scores on both awareness of illness (mean 1.1, s.d.=0.7, range 1–2) and relabelling of symptoms (mean 0.3, s.d.=0.6, range 0–2). The ‘aware, incorrect attributers’ group (n=14) had high scores on the awareness scale (mean 5.1, s.d.=0.8, range 4–6) but low scores on the scale measuring relabelling of symptoms (mean 0.7, s.d.=0.9, range 0–2). The ‘aware, correct attributers’ group (n=24) had high scores on both awareness of illness (mean 4.6, s.d.=1.0, range 3–6) and relabelling of symptoms (mean 3.0, s.d.=0.8, range 1–4). On the WCST, mean perseverative error scores for the ‘unaware’, ‘aware, correct attributers’ and ‘aware, incorrect attributers’ groups were 22.7 (s.d.=15.8), 13.0 (s.d.=5.3) and 13.7 (s.d.=7.4) respectively (F=4.714, d.f.=54, P=0.01). Scheffe's post hoc test showed that the ‘unaware’ group committed significantly more perseverative errors than either ‘aware, incorrect attributers’ (P=0.04) or ‘aware, correct attributers’ (P=0.03). The total recall mean scores of the HVLT–R for ‘unaware’, ‘aware, correct attributers’ and ‘aware, incorrect attributers’ were 19.5 (s.d.=5.7), 23.1 (s.d.=5.5) and 22.1 (s.d.=7) respectively. There was no statistically significant group difference, although a trend level of difference between the ‘aware, correct attributers’ and the ‘unaware’ groups was evident (P=0.06, two-tailed, HVLT–R total recall). Group differences were unchanged after controlling for the effect of premorbid IQ.

Fig. 1 The pattern of sub-scale scores provides evidence that there are three distinct groups who differ along two dimensions of insight (maximum score for awareness of illness scale, 6; maximum score for relabelling of symptoms, 4).

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate the existence of three groups differing in their awareness of illness and their ability to label experiences as symptoms of their illness. To our knowledge, this study is the first to provide empirical validation of Flashman & Roth's model (Reference Flashman, Roth, Amador and DavidFlashman & Roth, 2004). The dimensions may not be independent (and are effectively hierarchical) since unawareness of illness implies that symptoms cannot be relabelled.

Our findings shed light on the relationship between executive function and memory in the unaware and aware groups. Here, as predicted, the unaware group evidenced significantly more executive impairment (e.g. more perseverative errors on the WCST) and a trend for more working memory impairment than the aware group. This observation supports existing literature on the specific association between the unawareness dimension of insight and executive dysfunction in schizophrenia (Reference Mohamed, Fleming and PennMohamed et al, 1999). The WCST is a well-known measure of prefrontal executive functioning. The task requires problem-solving strategies, in addition to working memory components (e.g. remembering prior response and associated feedback needed to select a new response; Reference Gold, Carpenter and RandolphGold et al, 1997). In our experiment the unaware group had impaired executive functioning as measured by the WCST. However, the aware groups were not clinically impaired on the WSCT (‘below average’ according to the WSCT manual). Similarly, the aware group were not clinically impaired on the HVLT–R (less than 1 s.d. below mean for aware v. 2 s.d. below the mean for the unaware group; using healthy controls from the HVLT–R manual). By extension we suggest the working memory component was relatively more spared in the aware groups. This is commensurate with Flashman & Roth's suggestion that the inability to hold symptom information online while comparing it with past experiences impedes one's ability to accurately label current symptoms as abnormal, which manifests as unawareness of illness (Reference Flashman, Roth, Amador and DavidFlashman & Roth, 2004). Collectively, our study suggests that people with schizophrenia have better executive skills when insight is associated with a high degree of awareness of their clinical symptoms. To a lesser extent, perhaps working memory also contributed to inaccuracy of symptom labelling in the unaware group.

Previous studies have shown that insight improves following cognitive skills training and psychoeducation (Reference Nieznanski, Czerwinska and ChojnowskaNieznanski et al, 2002) and insight-enhancing psychotherapy (Reference SilverSilver, 2003). Our findings suggest that efforts to improve insight through psychotherapy and psychoeducation might be more successful in helping those who misattribute their symptoms but are aware of their illness. This is consistent with the report of a recent study by Rathod et al (Reference Rathod, Kingdon and Smith2005), who found that cognitive–behavioural therapy improved their patients’ ability to relabel symptoms as pathological but did not significantly alter the patients’ awareness of their illness. Our study therefore highlights both the clinical and theoretical importance of the separation of symptom misattribution from unawareness of illness in schizophrenia. Future therapeutic studies using insight as an outcome measure should measure cognitive function and differentiate between the three groups described here.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.