Multimorbidity is usually defined as two or more long-term conditions co-occurring in an individual. Although the terms multimorbidity and comorbidity are often used interchangeably, comorbidity implies an index condition associated with one or more other conditions (and is thus often defined by specialists), whereas multimorbidity does not imply that any one condition is more important than another. Multimorbidity is common and is often the norm rather than the exception in those with long-term conditions.Reference van den Akker, Buntinx, Metsemakers, Roos and Knotterus1 It is a significant and growing issue for patients, health professionals and healthcare systems worldwide.

Although most individuals with long-term conditions have more than one,2 healthcare systems throughout the world are predominately organised around a ‘single-disease’ approach. Multimorbidity in mental health has to date been relatively underresearched and data for how best to address the problem are limited. Here we summarise what is known about the extent of multimorbidity in psychiatric disorders and consider ways in which psychiatry might respond to the challenge.

Long-term physical health morbidity and mental illness

The fact that life expectancy for those with major mental illness is 20 years less for men and 15 years less for women is a stark statistic of health inequality. The close relationship between physical and mental health outcomes has long been recognised and several recent high-profile reports have highlighted a need for much greater integration. No Health without Mental Health,2 Long-term Conditions and Mental Health,3 How Mental Illness Loses out in the NHS 4 and the recent Schizophrenia Commission report The Abandoned Illness 5 are a few examples. A common thread is that long-term physical conditions and mental health problems very often co-occur, act synergistically and have negative effects on levels of disability, with longer hospital stays, increased cost and increased mortality.

The scale of the problem and the impact of social deprivation

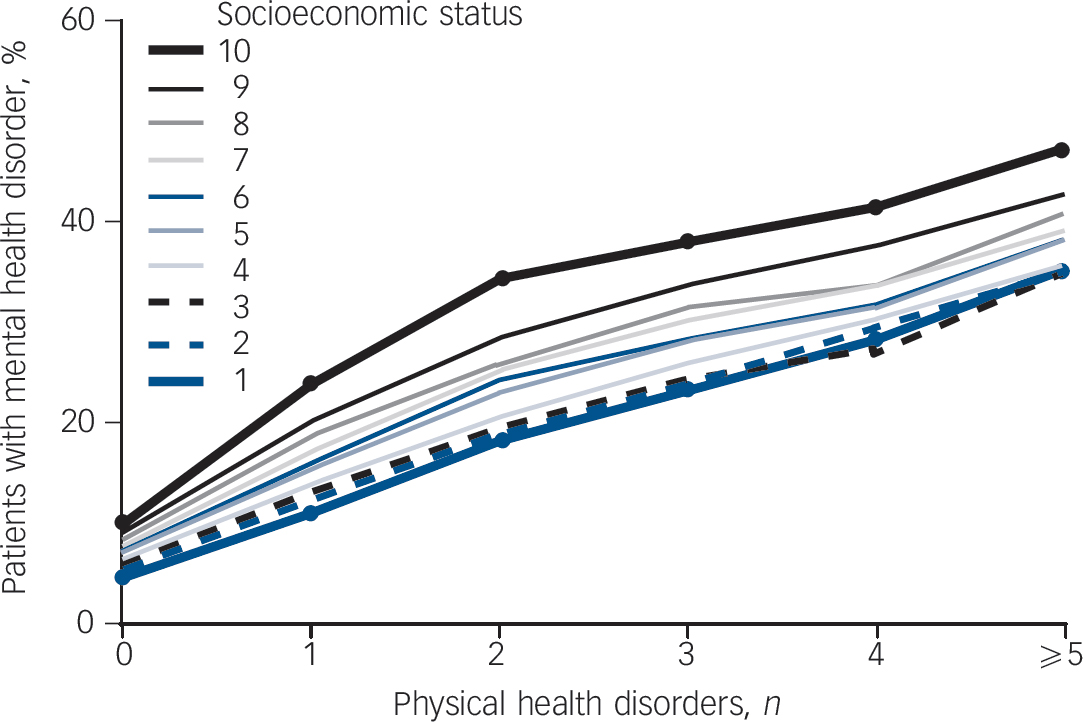

Multimorbidity was previously considered a problem for elderly populations but recent work has found this not to be the case. A study of almost 1.8 million people within 314 primary care practices in Scotland found that more people with multimorbidity were aged below 65 than were aged above 65 and similar findings have been observed internationally.Reference Barnett, Mercer, Norbury, Watt, Wyke and Guthrie6 Socioeconomic deprivation has a strong and consistent association with multimorbidity. In the Scottish primary care study, prevalence rates of physical and mental health comorbidity were almost twice as high in the most deprived areas (11%) compared with the most affluent areas (5.9%) (Fig. 1).Reference Barnett, Mercer, Norbury, Watt, Wyke and Guthrie6 Furthermore, the onset of multimorbidity occurred up to 15 years earlier in the most deprived areas compared with the most affluent areas.

This socioeconomic gradient in the association between physical and mental health will come as no surprise to general practitioners (GPs) and psychiatrists working in deprived areas of the UK - an issue highlighted in the ‘General Practitioners at the Deep End’ project (involving 100 general practices in the most deprived populations in Scotland),Reference Watt7 where a common theme was the difficulty in adequately addressing a multitude of interrelated medical, psychiatric, substance misuse and social problems in the context of limited time, limited resources and low availability of high-quality services such clinical psychology.

There must be real concerns that multimorbid psychiatric patients (concentrated in more deprived areas) will not be well served by changes resulting from the new Health and Social Care Bill in England. Anxieties about the likely impact of these National Health Service (NHS) reforms on patients with physical and mental health problems are a prominent feature of the recent King's Fund report, which highlights that ‘the interaction between comorbidities and deprivation makes a significant contribution to generating and maintaining inequalities’.3 This report urges clinical commissioning groups to prioritise the integration of physical and mental healthcare to improve both patient outcomes and longer-term productivity.

Managing multimorbidity in mental health through more integrated care

The care of patients with multimorbidity can be complex and may involve multiple secondary care specialists who separately liaise with the primary care team. The communication challenges this presents can lead to fragmented and inconsistent care, particularly for patients with major mental illness.3 These problems are compounded by the reality that patients with mental illness and comorbid physical problems often do not receive the same level of assessment and treatment for their physical problems as patients without mental illness.Reference Thornicroft, Brohan, Rose, Sartorius and Leese8 There are likely to be opportunities in the future to improve communication between primary and secondary care, for example, by improved linking of electronic databases used for chronic disease monitoring (such as diabetes) with secondary care psychiatric databases, with a view to better sharing of information on physical health.

Fig. 1 Physical and mental health comorbidity and the association with socioeconomic status.

On the socioeconomic status scale, 1 is the most affluent and 10 the most deprived. Reproduced with permission from Barnett et al. Reference Barnett, Mercer, Norbury, Watt, Wyke and Guthrie6

It seems clear that we need models of care that allow a much more integrated approach to diagnosing, monitoring and treating multimorbidity in patients with mental illness, particularly in areas of social and economic deprivation. Greater integration of psychiatric services with primary care and with specialist medical services is clearly vital but evidence on how best to achieve this is limited. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines integrated care as the management and delivery of healthcare along a continuum of preventive and curative services, according to patient needs over time and across different levels of the health system. Integrated care can be cost-effective, patient-centred, equitable and ‘locally-owned’ but there is also a risk that a broad continuum of integration threatens existing high-quality services.

Although there is some evidence that integrated care models - which include chronic disease management approaches, case management and enhanced multidisciplinary teamwork - may have long-term benefits in treating multimorbidity,Reference Smith, Soubhi, Fortin, Hudon and O'Dowd9 there has been no systematic evaluation of these interventions in multimorbid patients with severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia. Collaborative care models for the management of depression involve a mental health specialist, a primary care practitioner and a case manager with, in general, good outcomesReference Gilbody, Bower, Fletcher, Richards and Sutton10 - this tripartite model may be a useful approach for treating multimorbid mental illness but it has not yet been formally evaluated.

Another potential avenue for improving the integration of physical and mental healthcare is to build on the success of liaison psychiatry services that at present are almost exclusively hospital based. One of the key recommendations from the NHS Confederation's recent briefing report Liaison Psychiatry - The Way Ahead is that liaison psychiatry services could be developed further to provide community-based services and training.11

How should psychiatry respond?

Policy makers in the UK and internationally need to plan reorganisations of both mental health and physical health services in ways that can equitably address the health inequalities noted earlier. Careful attention needs to be given to how best to get mental health specialists and GPs working together effectively and whether this multimorbidity work can be incentivised, particularly in areas of social deprivation. The Royal College of General Practitioners and the Royal College of Psychiatrists have started to work together on this issue - for example, with the recent publication of the Positive Cardiometabolic Health Resource (Lester UK Adaptation)Reference Lester, Shiers, Rafi, Cooper and Holt12 - but this is an area in need of much further development. Arguably the most pressing need is to develop interventions to reduce the extraordinarily high rates of smoking in major mental illness.

In the longer term, addressing multimorbidity will have major implications for the way in which all clinicians involved with mental health - as well as GPs - are trained and work. The current disconnection between secondary care psychiatric services (which are focused on mental health outcomes) and primary care services, which are often not fully engaged in the physical healthcare of their patients with mental illness, needs to be addressed as a matter of urgency.

In the short- to medium-term, psychiatrists should seek to improve the degree to which they engage with the physical health needs of their patients. This could obviously take many forms, including better assessment and monitoring, closer liaison with GPs, supporting and delivering exercise, weight management and smoking cessation programmes, improving antipsychotic prescribing skills and recognising the opportunities within early intervention services for addressing the long-term physical health needs of young people with major mental illness.Reference Bailey, Gerada, Lester and Shiers13 Longer-term, the medical academic community should come together to design and test creative new interventions specifically for multimorbidity in mental health in order to gather the evidence for new innovations in service organisation and delivery. These interventions should be at several levels, from healthcare system changes and large-scale integrated or collaborative care models, to focused interventions in high-risk groups, such as young adults with first-episode psychosis living in deprived communities.

Conclusions

Multimorbidity in mental health may be a relatively new concept for psychiatry but it is likely to become increasingly important in the future. This issue may be particularly acute for psychiatric practice in the UK, given the current recruitment crisis and the biggest health service reforms for a generation, both of which risk further inequality and disadvantage for patients with mental illness who have complex needs. Given the central role of mental illness within the multimorbidity continuum, it is our contention that psychiatrists, GPs, researchers and policy makers urgently need to discuss how best to develop and evaluate services that will improve physical, psychological and social outcomes for our patients.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.