Monitoring routine clinical practice is intended to produce information on the probability of different outcomes and on variables that may affect outcome (Reference BlackBlack, 1999; Reference Salvador-CarullaSalvador-Carulla, 1999). Key issues are the inclusion of all patients in longterm observations and the use of outcome indicators routinely adopted in everyday clinical practice (Reference Harrison and EatonHarrison & Eaton, 1999; Reference Thornicroft and TansellaThornicroft & Tansella, 1999; Reference Barbui, Tognoni and GarattiniBarbui et al, 2002).

The Italian psychiatric system gives high priority to out-patient care delivered by community mental health centres (CMHCs). Individuals with psychological and psychiatric problems in a specific catchment area are all followed by the CMHC for that area. Continuity of care is considered a basic quality requirement, essential for following patients in their own context of life for a long time (Reference Tansella, Micciolo and BiggeriTansella et al, 1995). To date, however, continuity of care has been investigated rarely in Italian CMHCs. Morlino et al (Reference Morlino, Martucci and Musella1995) explored the probability of leaving care in a university psychiatric out-patient clinic but this did not cover a specified catchment area, which might have influenced the overall drop-out rate (82% at 3 months). The present outcome study followed all patients who had a first contact with a CMHC during a 1-year period for 24 months; the purpose was to estimate the probability of leaving care and to identify subgroups of patients most likely to drop out.

METHOD

Study area

The Magenta Community Psychiatric Service is a public agency that provides psychiatric care to 160 000 residents in a suburban area near Milan. Its catchment area consists of two main sub-areas: the Magenta area (130.76 km2 and about 100 000 residents) and the Abbiategrasso area (202.61 km2 and about 60 000 residents).

The Magenta Community Psychiatric Service consists of one psychiatric ward in a general hospital, one psychiatric residential rehabilitative centre, two community mental health centres (the Magenta CMHC providing care to the Magenta residents, and the Abbiategrasso CMHC providing care to the Abbiategrasso residents) and two unstaffed apartments. The psychiatric ward in the Magenta general hospital is a 16-bed in-patient unit generally used for acute episodes. This ward offers acute in-patient care, liaison services to other hospital units and a 24-hour emergency service to both the Magenta and the Abbiategrasso residents.

The CMHCs are the operational units in charge of managing all psychiatric services provided to patients from their catchment areas. All but emergency cases are expected to have their first contact with public mental health care in these units. The CMHCs also are charged to act as the psychiatric interface of the network of general practitioners providing primary general care to all residents. The Magenta CMHC catchment area comprises various small towns located in a mainly rural territory. Population density is 772.75 inhabitants per square kilometre. The main economic activities are farming and traditional manufacturing. The CMHC serves 85 809 adult residents (total population is 101 045). Further details of routine clinical work and costs of this facility can be found elsewhere (Reference Percudani, Fattore and GallettaPercudani et al, 1999; Reference Fattore, Percudani and PugnoliFattore et al, 2000).

Study population

The study was carried out at the Magenta CMHC. In 1992 an administrative database was developed to routinely collect service utilisation data (Regione Lombardia Settore Sanità e Igiene, 1992) as part of the computerised psychiatric information system of the local regional health authority. From this database socio-demographic and clinical information was extracted on all patients who had had a first contact with the CMHC from January to December 1994. All these patients were followed for 24 months. Patients were grouped in six ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1992) diagnostic categories: schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (F2 diagnoses); mood disorders (F3 diagnoses); neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (F4 diagnoses); disorders of adult personality and behaviour (F6 diagnoses); ‘mental retardation’ (F7 diagnoses) (hereafter, learning disability); and other diagnoses (patients not included in F2, F3, F4, F6 or F7).

Outcome

The total number of months of contact with the CMHC during the study period was recorded. Patients who failed to return after the last out-patient visit, even though a new appointment had been established, were regarded as having dropped out. Patients who remained in contact with the out-patient service during the whole study period were considered ‘still followed up’ and patients who discontinued the contact in agreement with the treating psychiatrists were regarded as ‘discharged’.

Statistical analysis

Rates of first-contact patients by diagnosis were calculated by dividing the total number who had had a first contact with the CMHC during the 12-month recruitment period by the resident population. Rates of first-ever-contact patients by diagnosis were calculated by dividing the number of patients with no previous psychiatric contacts with any other mental health facilities who had had a first contact with the CMHC during the 12-month recruitment period by the resident population. Univariate comparisons between patients who dropped out, were ‘discharged by agreement’ and those who stayed in treatment were performed using χ2 statistics, and a Kaplan—Meier curve estimated the survival probability (continuity of care) over the 24-month follow-up. A Cox regression analysis was carried out to determine the role of independent variables in the probability of discontinuing contact with the out-patient service. All calculations were done using Stata 4.0 (StataCorp, 1995).

RESULTS

Rates of first-contact and first-ever-contact patients

During the 12-month recruitment period 1145 subjects had at least one contact with the CMHC; of these, 330 were at their first contact (29%). The overall 1-year incidence of first-contact patients was nearly 33 per 10 000 inhabitants; of these, 26 per 10 000 were at their first-ever contact with a psychiatric service (Table 1). Incidence rates were high for patients suffering from neurotic disorders and low for psychosis and learning disability (Table 1).

Table 1 Incidence of first-contact and first-ever-contact patients per 10 000 inhabitants by diagnostic group

| Diagnosis | All first-contact patients (n=330)1 | First-ever-contact patients (n=262)1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | Rate per 10 000 (95% CI) | n | (%) | Rate per 10 000 (95% CI) | |

| Psychotic disorders | 24 | (7.3) | 2.3 (1.5-3.5) | 18 | (6.9) | 1.78 (1.0-2.8) |

| Affective disorders | 73 | (22.3) | 7.2 (5.6-9.0) | 50 | (19.2) | 4.94 (3.6-6.5) |

| Neurotic disorders | 114 | (34.8) | 11.2 (9.3-13.5) | 97 | (37.3) | 9.59 (7.7-11.7) |

| Personality disorders | 49 | (14.9) | 4.8 (3.5-6.4) | 40 | (15.4) | 3.95 (2.8-5.3) |

| Learning disability | 15 | (4.6) | 1.4 (0.8-2.4) | 10 | (3.8) | 0.98 (0.4-1.8) |

| Others | 53 | (16.2) | 5.2 (3.9-6.8) | 45 | (17.3) | 4.45 (3.2-5.9) |

| Total | 330 | (100.0) | 32.6 (29.2-36.3) | 262 | (100.0) | 25.9 (22.8-29.2) |

Characteristics of the 330 first-contact patients

The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 2. The majority were female, only one-third were over 50 years of age, half were married and a minority lived alone. Sixty-four had had previous psychiatric contacts and the others were first-evercontact patients. Neurotic disorders were the most common diagnoses, followed by affective disorder. Patients suffering from psychotic disorders accounted for 7% of the total sample. Nearly half of the patients received no prescription for psychotropic drugs at first contact.

Table 2 Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of all first-contact patients with the Magenta community psychiatric service over a 12-month period

| Variable | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 200 | (60.6) |

| Male | 130 | (39.3) |

| Age (years) | ||

| 17-30 | 105 | (31.8) |

| 31-50 | 124 | (37.5) |

| 51-70 | 70 | (21.2) |

| 71-88 | 31 | (9.3) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 117 | (35.4) |

| Married | 167 | (50.6) |

| Separated | 12 | (3.6) |

| Widowed | 34 | (10.3) |

| Living situation | ||

| Alone | 43 | (13.0) |

| Not alone | 287 | (86.9) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 296 | (89.7) |

| Not employed | 34 | (10.3) |

| Previous psychiatric contacts with other mental health services1 | ||

| No | 262 | (80.4) |

| Yes | 64 | (19.6) |

| Diagnosis2 | ||

| Psychotic disorders | 24 | (7.3) |

| Affective disorders | 73 | (22.2) |

| Neurotic disorders | 114 | (34.7) |

| Personality disorders | 49 | (14.9) |

| Learning disability | 15 | (4.6) |

| Others | 53 | (16.2) |

| Prescription of psychotropic drug at first contact | ||

| No | 153 | (46.3) |

| Neuroleptic only | 24 | (7.3) |

| Antidepressant only | 38 | (11.5) |

| Benzodiazepine only | 39 | (11.8) |

| Combination | 76 | (23.0) |

Outcome

After 2 years of follow-up 46% of patients had dropped out, one-third were still followed up, a quarter discontinued the contact in agreement with the treating psychiatrists and two patients had died (of causes unrelated to the psychiatric diagnosis) (Table 3).

Table 3 Fate of first-contact patients after 2 years of follow-up

| Outcome | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Dropped out | 153 | (46.4) |

| Discharged | 80 | (24.2) |

| Still followed up | 95 | (28.8) |

| Deceased | 2 | (0.6) |

Differences between patients who dropped out, were ‘discharged by agreement’ and who stayed in treatment

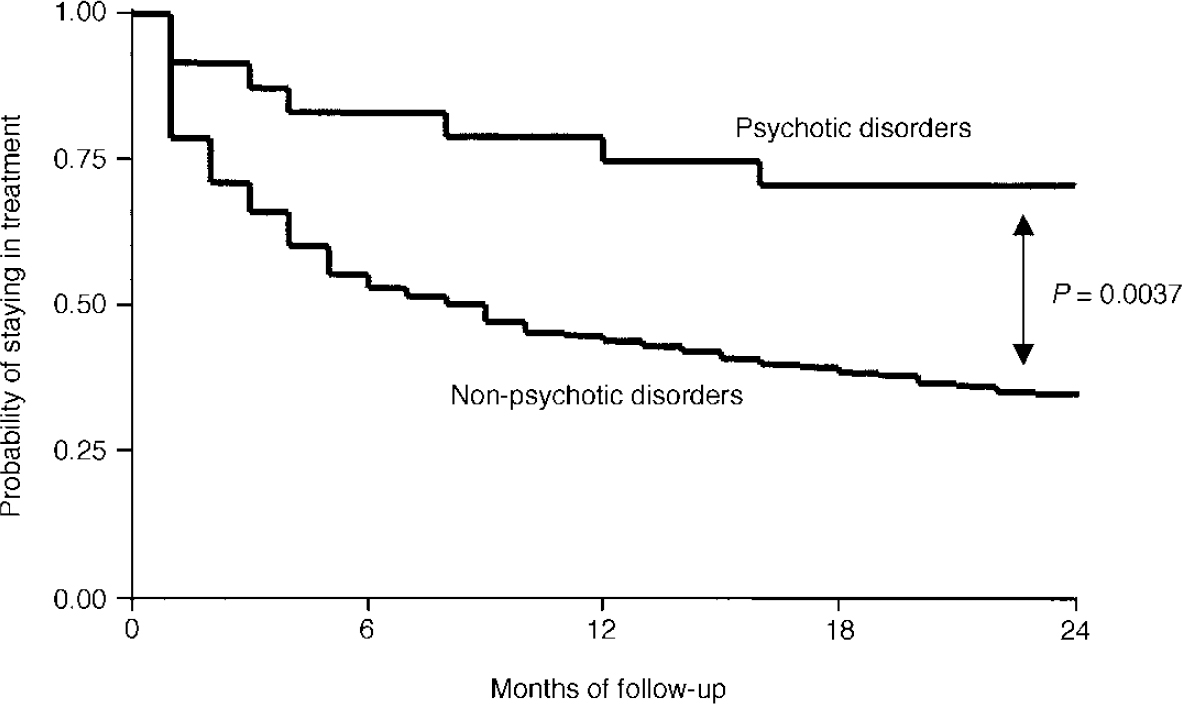

The distribution of patients who dropped out, were discharged and who continued treatment showed no significant differences in socio-demographic and clinical variables (Table 4). However, more continuing than discharged and drop-out patients were suffering from psychotic disorders, and more drop-outs than continuing patients suffered from neurotic and personality disorders. In addition, more continuing than discharged and dropout patients were prescribed psychotropic drugs at first contact. The survival probability of patients with and without a psychotic disorder over the 24 months of follow-up showed that the former were less likely to drop out (Fig. 1). A multivariate Cox regression analysis was carried out to determine the independent contribution of socio-demographic and clinical variables to the probability of leaving care. Using patients with psychosis as a reference category, patients with neurotic and personality disorders were more likely to drop out (Table 5). In addition, male gender was a risk factor for dropping out. Table 6 presents the distribution of drop-outs and patients continuing treatment by number of contacts per month with the CMHC. There were no real differences.

Fig. 1 Kaplan—Meier curve illustrating the survival probability (continuity of care) by diagnosis. Patients with psychotic disorders (F2 diagnoses) were more likely to survive than patients with non-psychotic disorders (logrank test). Only those patients who dropped out of treatment or who were still followed up after 2 years were included in this analysis.

Table 4 Socio-demographic and clinical variables of patients who dropped out, were discharged by agreement and those still followed up

| Dropped out (n=153) | Discharged (n=80) | Still followed up (n=95) | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 90 | (58.8) | 50 | (62.5) | 59 | (62.1) | 0.813 |

| Male | 63 | (41.2) | 30 | (37.5) | 36 | (37.9) | |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 17-30 | 47 | (30.7) | 23 | (28.8) | 35 | (36.8) | 0.227 |

| 31-50 | 55 | (35.9) | 28 | (35.0) | 40 | (42.1) | |

| 51-70 | 37 | (24.2) | 17 | (21.3) | 15 | (15.8) | |

| 71-88 | 14 | (9.2) | 12 | (15.0) | 5 | (5.3) | |

| Living situation | |||||||

| Alone | 25 | (16.3) | 7 | (8.8) | 11 | (11.6) | 0.231 |

| Not alone | 128 | (83.7) | 73 | (91.3) | 84 | (88.4) | |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Employed | 17 | (11.1) | 8 | (10.0) | 9 | (9.5) | 0.912 |

| Not employed | 136 | (88.9) | 72 | (90.0) | 86 | (90.5) | |

| Previous psychiatric contacts with other mental health services1 | |||||||

| No | 124 | (82.7) | 65 | (82.3) | 71 | (74.7) | 0.275 |

| Yes | 26 | (17.3) | 14 | (17.7) | 24 | (25.3) | |

| Diagnosis2 | |||||||

| Psychotic disorders | 7 | (4.6) | 0 | (0.0) | 17 | (17.9) | <0.001 |

| Affective disorders | 30 | (19.9) | 17 | (21.3) | 25 | (26.3) | |

| Neurotic disorders | 59 | (39.1) | 31 | (38.8) | 24 | (25.3) | |

| Personality disorders | 26 | (17.2) | 9 | (11.3) | 14 | (14.7) | |

| Learning disability | 3 | (2.0) | 10 | (12.5) | 2 | (2.1) | |

| Others | 26 | (17.2) | 13 | (16.3) | 13 | (13.7) | |

| Prescription of psychotropic drug at first contact | |||||||

| Yes | 81 | (52.9) | 30 | (37.5) | 66 | (69.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 72 | (47.1) | 50 | (62.5) | 29 | (30.5) | |

Table 5 Cox regression analysis to determine the independent role of socio-demographic and clinical variables on the probability of leaving care (this analysis included only those patients who dropped out of treatment or who were still followed up after 2 years; the dependent variable was time to discontinuing contacts)

| Independent variable | Hazard ratio1 | (95% Cl) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1 | ||

| Male | 1.45 | (1.01-2.07) | 0.040 |

| Age (years) | |||

| 17-30 | 1 | ||

| 31-50 | 1.26 | (0.82-1.94) | 0.288 |

| 51-70 | 1.68 | (1.00-2.82) | 0.050 |

| 71-88 | 1.60 | (0.78-3.27) | 0.198 |

| Living conditions | |||

| Alone | 1 | ||

| Not alone | 0.77 | (0.47-1.27) | 0.323 |

| Employment status | |||

| Not employed | 1 | ||

| Employed | 0.75 | (0.43-1.30) | 0.317 |

| Previous psychiatric contacts with other mental health services | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.49 | (0.95-2.33) | 0.076 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Psychotic disorder | 1 | ||

| Affective disorder | 2.22 | (0.94-5.24) | 0.066 |

| Neurotic disorder | 2.36 | (1.48-7.65) | 0.004 |

| Personality disorder | 2.59 | (1.10-6.08) | 0.029 |

| Learning disability | 1.94 | (0.49-7.67) | 0.340 |

| Others | 2.53 | (1.03-6.23) | 0.043 |

| Prescription of psychotropic drugs at first contact | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.70 | (0.49-1.00) | 0.056 |

Table 6 Number of contacts per month for those patients who dropped out of treatment and those who were still followed up after 2 years

| Number of contacts per month | Dropped out (n=153) | Still followed up (n=95) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Between 0.04 and 1 | 77 | (50.7) | 54 | (56.8) | 0.343 |

| More than 1 | 75 | (49.3) | 41 | (43.2) | |

DISCUSSION

Monitoring community psychiatric services has been suggested as a possible way of supporting and guiding everyday clinical practice (Reference MarksMarks, 1998; Reference Baron and WeiderpassBaron & Weiderpass, 2000; Reference Knapp, Almond, Percudani, Maj and SartoriusKnapp et al, 2000; Reference Barbui, Tognoni and GarattiniBarbui et al, 2002). The goals of community psychiatry are to identify people suffering from psychiatric problems and to provide long-term care (Reference Tansella, Micciolo and BiggeriTansella et al, 1995). Therefore, rates of first-contact patients and rates of patients leaving care are key outcome indicators in this setting.

Annual rates of first-contact patients in the Magenta area were slightly higher than in other Italian catchment areas. We estimated that out of 10 000 inhabitants, 33 contacted the out-patient service in 1 year, compared with 20 in the Verona area (Reference Balestrieri, Meneghelli and TansellaBalestrieri et al, 1992) and 26 in the Portogruaro area in 1990 (Reference De Salvia and RoccoDe Salvia & Rocco, 1992). These figures suggest that the Magenta CMHC is as accessible as other Italian community-oriented psychiatric facilities.

Drop-out rates in routine clinical practice

Continuity of care, considered a cornerstone of community psychiatry, has been monitored rarely in the Italian context of psychiatric care. We found that nearly half of the first-contact patients were no longer in treatment after 2 years of follow-up. This is hardly comparable with figures from the literature because we adopted a very naturalistic approach, avoiding any form of patient selection and following all first-contact patients for a long time. Depending on study design and definition, dropout rates in routine clinical practice vary between 20 and 60% (Reference Swett and NoonesSwett & Noones, 1989; Reference Mahneke, Dragsted and JensenMahnekeet al, 1993; Reference Pang, Lum and UngvariPanget al, 1996; Reference Tehrani, Krussel and BorgTehraniet al, 1996; Reference Killaspy, Banerjee and KingKillaspyet al, 1999), compared with estimates in experimental studies of around 30% of patients leaving care (Reference Barbui and HotopfBarbui & Hotopf, 2001). Morlino et al (Reference Morlino, Martucci and Musella1995), in a study conducted in Italy, estimated an overall drop-out rate of 82% at 3 months but the study setting was a university department with no particular catchment area. In this rather special context of care many patients arrived from far away, and this might explain the high drop-out rate. No association was detected between diagnosis and continuity of care; in contrast, two studies in the USA found that patients with schizophrenia (Reference Young, Grusky and JordanYoung et al, 2000) and personality disorders (Reference Cohen, Edstrom and Smith-PapkeCohen et al, 1995) were more likely to drop out. The present study indicated that in the Italian context of care, patients with psychosis are more likely to stay in treatment, and patients with neurotic and personality disorders are more likely to leave.

Study limitations

A first limitation of this study is the possibility of unreliability of the mental health information system, which might have missed some data. Although this possibility cannot be ruled out completely, the reliability of the definition of drop-outs was checked externally by analysing each patient's clinical chart and recording whether there was a failure to return after the last out-patient visit, even though a new appointment was planned. This double-check approach was adopted to be sure that the drop-out category reflected people who failed contact with the psychiatric service, and not a failure within the information system. A double-check approach, namely information collected at the index contact and information from the computerised system, was used also to identify first-contact patients. First-ever-contact patients, however, were identified using only information collected at the index contact, because the computerised system works in such a way that each psychiatric service has access only to its own service utilisation data.

A second limitation of this study comes from the lack of outcome data on patients who left care in comparison with those who stayed in treatment. Outcome data in our study would have provided an external check on the validity of the drop-out category and would have provided information on whether drop-out status is a matter of concern in the Italian context of psychiatric care. In fact, there is the possibility that some terminations of treatment might have been for good reasons, such as improvement in symptoms or moving out of the catchment area, and it is not easy to make a clear distinction between appropriate and non-appropriate terminations without following up all patients, including those who interrupted contacts. Younget al (Reference Young, Grusky and Jordan2000) examined outcomes for continuing and drop-out patients and showed that average outcomes improved for both groups, and patients who left treatment and could be located for follow-up were less severely ill and showed the greatest improvement and the best outcomes. Killaspy et al (Reference Killaspy, Banerjee and King2000) assessed the outcome of attenders and non-attenders in a cohort of 365 UK psychiatric out-patients and found that those who failed to attend were more unwell and more socially impaired than those who kept their appointments.

Implications for practice

The finding that patients who stayed in treatment were more likely to suffer from psychotic disorders might be explained by the strong commitment of Italian CMHCs to providing care for people suffering from severe illness. Frankel et al (Reference Frankel, Farrow and West1989), in a UK out-patient facility, showed that patient factors were less important than aspects of the service in explaining non-attendance at out-patient appointments. In Italy, since the closure of mental hospitals, community psychiatric services have implemented strategies, attitudes and specific treatment plans to tackle the needs of patients with psychosis more than other patients (Tansella et al, Reference Tansella, De Salvia and Williams1987, Reference Tansella, Micciolo and Biggeri1995). A comparison between South Verona and Groningen showed that more patients in South Verona received community care within 2 weeks after hospital discharge, suggesting better continuity of care for severe cases in that specific system of care (Reference Sytema, Micciolo and TansellaSytema et al, 1997). However, our data did not suggest that there was any selection of patients, at least judging from the total number of contacts per month with the CMHC, which was similar for patients who left care and those who stayed in treatment.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

• Nearly half of the first-contact patients were no longer in treatment after 2 years of follow-up.

-

• Subjects suffering from neurotic and personality disorders were more likely to drop out in comparison with subjects suffering from psychosis.

-

• Continuity of care should be monitored routinely in community psychiatric services.

LIMITATIONS

-

• Generalisability may be limited, because the study was carried out in a single catchment area.

-

• Outcome data on patients who left care in comparison with those who stayed in treatment were not collected.

-

• Reasons for leaving care were not investigated.

Acknowledgements

This study would not have been possible without the collaboration of Anna Caimi, Valentina Mazzeo and the Magenta CMHC nursing staff.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.