Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), the purposeful destruction of one's body tissue without suicidal intent (e.g. cutting, burning, hitting, severe scratching), is a public health concern owing to high prevalence rates and risk for suicidal behaviour among both adolescents and adults.Reference Lewis, Seko and Joshi1 Increased awareness of the widespread impact of NSSI over the past 15 years has resulted in a growth of NSSI-focused research and media stories. These stories are varied and range from providing education and facts to perpetuating myths and/or graphic portrayals of NSSI. Despite this, and unlike suicide reporting guidelines (such as those published by the World Health Organization2 and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention3), there are no clear recommendations for journalists and reporters to follow to ensure responsible presentation of NSSI-related content. The goal of this editorial is to offer the first empirically informed, consensus-based guidelines for the responsible reporting and depicting of NSSI in the media.

Rationale for media guidelines

Beyond the prevalence of NSSI-related content in the media, there are multiple reasons to consider the need for media guidelines pertinent to NSSI. First, how mental health difficulties are portrayed by news media may contribute to stigma about mental illness.Reference Corrigan, Powell and Michaels4 In line with this, guidelines for the responsible reporting of suicide set forth by the World Health Organization2 exemplify the importance of careful, destigmatising word choice. Even well-intentioned efforts may inadvertently propagate myths and misconceptions regarding NSSI (e.g. that it is attention-seeking, manipulative), which can increase stigma, contribute to unhelpful public perceptions about the behaviour and those who engage in it, and leave individuals who self-injure feeling marginalised and less apt to seek help.Reference Baker and Lewis5 Considering the stigma associated with NSSI, attention to and guidance for the representation of NSSI in the media seems especially warranted.

Second, NSSI is often depicted in ways that make recovery seem impossible or that justifies its use. For example, research examining online NSSI content indicates that NSSI is often portrayed using hopeless tones that emphasise emotional pain without mention of encouragement of recovery; in other cases, NSSI is presented as an acceptable means of coping with emotional pain.Reference Lewis, Seko and Joshi1,Reference Baker and Lewis5 Hence, mention of alternative means of coping is rare. Such portrayals, especially if repeatedly accessed, may lead to continued NSSI and thwarted help-seeking efforts.Reference Baker and Lewis5

Third, NSSI imagery and detailed text-based depictions, especially if graphic in nature (e.g. images of wounds, methods used), may provoke NSSI urges or even behaviour.Reference Baker and Lewis5 Consistent with guidelines for reporting on suicide, how NSSI methods are depicted must be considered.

Finally, media professionals are well positioned to ensure that media representations of NSSI are accurate, evidence-based and hopeful. Likewise, psychiatrists, psychologists and other healthcare professionals are well positioned to provide this education to media professionals. Indeed, evidence suggests that the ‘Papageno effect’, in which responsible media coverage of suicide can play a protective role against suicide by highlighting how individuals struggling with suicidal thoughts can use alternative strategies to cope in a healthy and positive way,Reference Niederkrotenthaler, Voracek, Herberth, Till, Strauss and Etzersdorfer6 may extend to responsible coverage of NSSI. For instance, provision of hopeful messages concerning recovery may elicit more positive attitudes towards recovery.Reference Lewis, Seko and Joshi1 Hence, while media representations can and should validate the inherent challenges associated with NSSI, ensuring that hopeful messages are offered in tandem is important.

Development of media guidelines

We first synthesised extant literature on how media portrayals of NSSI may perpetuate stigma, limit efforts to seek help and lead to increases in NSSI urges and behaviour (identified articles are listed in the supplementary material, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.191). For example, research suggests that graphic photographs portraying NSSI may encourage the behaviour among some individuals;Reference Lewis, Seko and Joshi1 therefore, we recommend avoiding use of NSSI-related images. Additionally, we reviewed media guidelines for reporting on suicide, as they are accepted as best practice and provide examples of clear and concise public health messaging. After drafting these guidelines, we adopted a collaborative approach encompassing diverse perspectives and consulted with a range of individuals (a physician; NSSI and suicide prevention researchers; members of the International Society for the Study of Self-Injury (ISSS), which comprises leading researchers, clinicians and individuals with lived experience; and a freelance journalist with a health specialty), who all offered feedback and provided a preliminary understanding of potential barriers to implementation. The guidelines were revised on the basis of their feedback. In summary, the guidelines articulated here reflect a synthesis of research, consultation with experts from various health professions, and many hours of discussion and whole-group review of guideline language (i.e. expert consensus). Our views are in line with those of the ISSS, whose mission is to promote the understanding, prevention and treatment of NSSI as well as to foster well-being among those with lived NSSI experiences and those affected by NSSI.

Overview of media guidelines

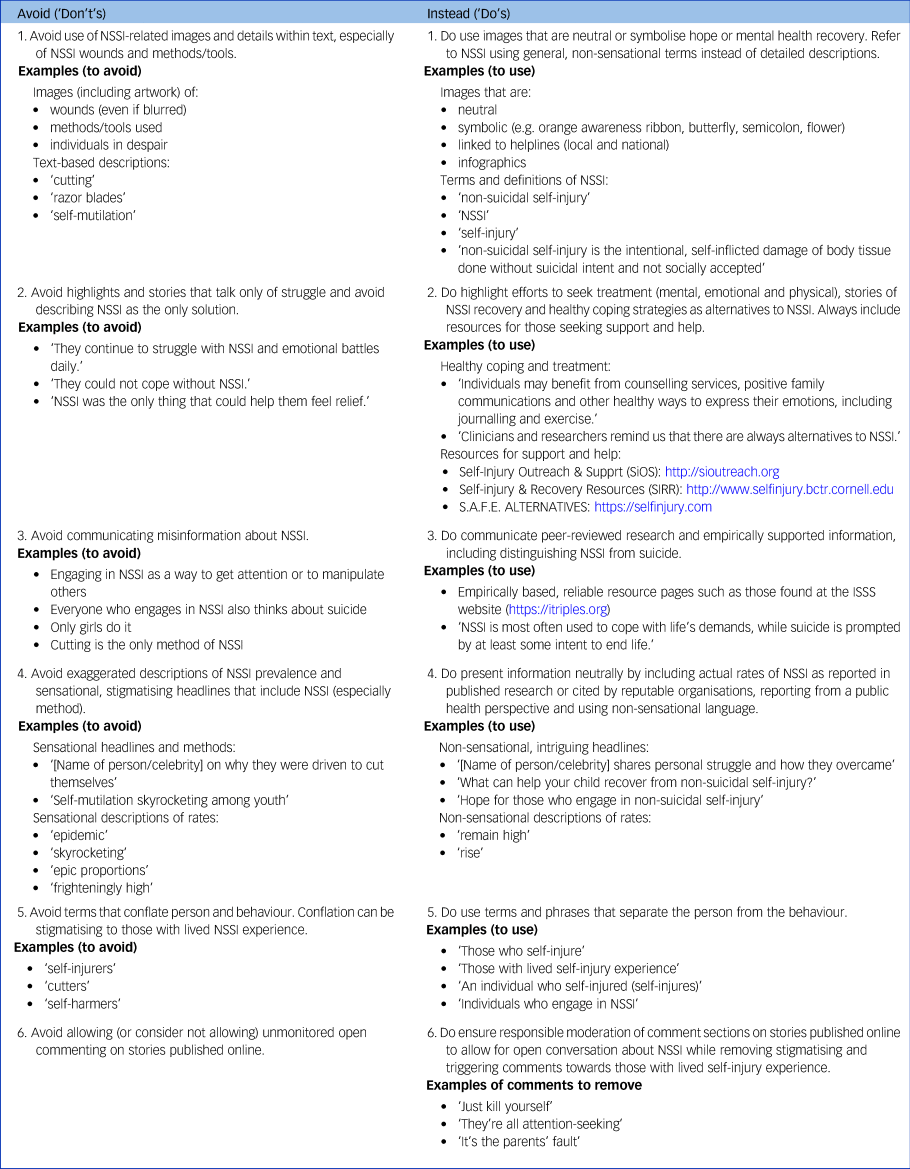

We provide six specific recommendations for depicting or reporting on NSSI in the media in ways that enhance the likelihood of appropriate and responsible coverage. Rather than simply advising what not to do, we offer alternative recommendations (Appendix; see also supplementary Fig. 1) and discuss them in greater detail in our full white paper.Reference Westers, Lewis, Whitlock, Schatten, Ammerman and Andover7 Based on the latest available research and expert consensus, media should make particular efforts to follow recommendations 1, 2 and 3. In brief, when depicting and reporting on NSSI, we recommend that media:

(1) avoid use of NSSI-related images and details within text, especially of NSSI wounds and methods/tools

(2) highlight efforts to seek treatment, stories of recovery, adaptive coping strategies as alternatives to NSSI, and updated treatment and crisis resources

(3) avoid misinformation about NSSI, by communicating peer-reviewed and empirically supported material, including distinguishing NSSI from suicide

(4) present information neutrally; avoid exaggerated descriptions of NSSI prevalence and sensational headlines that include NSSI, especially the method of NSSI

(5) use non-stigmatising language and avoid terms that conflate person and behaviour (e.g. ‘cutter’)

(6) ensure that online article comments are responsibly moderated.

Recommendations for social media

Many of the recommendations we advocate for traditional media, such as limiting content likely to perpetuate reinforcement of NSSI, are nearly impossible to implement on social media platforms. Even when guidelines clearly articulate what is and is not allowed on the platform, there are multiple ways of skirting restrictions on even the most responsible social platform, making rapid identification of problematic content or exchange difficult. Despite these challenges, however, there are remedial steps that social media platforms can take to reduce risk overall and increase timely removal of triggering material:

(a) post clear rules (e.g. no posting of triggering content, clear placement of trigger warnings)

(b) post clear response guidelines for individuals interacting with other users’ posts and easily activated flagging options so that clearly damaging or stigmatising responses can be quickly identified and removed

(c) utilise robust human and/or machine moderation protocols aimed at quickly identifying and responding to posts that breach platform guidelines

(d) apply meaningful consequences for repeat offenders (e.g. removal from the platform)

(e) regularly update guidelines, site moderators and/or algorithmic responses to incorporate new and emerging knowledge about relevant posting trends.

Development of algorithmic or machine learning methods for enforcing platform guidelines is a promising approach for mitigating risk to vulnerable populations, such as those who self-injure. Responsible platforms can and should include ‘help’ or ‘resources’ pop-ups that are triggered to appear when keywords or phrases, such as ‘cutting’, ‘self-harm’ or ‘self-injury’, are used. These can link to educational material and/or resources intended to support help-seeking and increased self-awareness.

Recommendations for disseminating these guidelines

The media are fast-paced and deadline-driven and rely on the importance of visuals and details. Media culture values free speech and independence, and recommendations such as those found in suicide reporting guidelines and the NSSI guidelines proposed here may appear to lack that flexibility. We recommend that healthcare professionals, media professionals and key stakeholders (e.g. psychiatrists, psychologists, paediatricians, parent groups, key advocacy groups) take a collaborative approach to these conversations. We welcome feedback from media professionals about these guidelines and potential barriers to implementation.

In addition to a collaborative approach, targeted strategies for dissemination are important in order to increase awareness among both media professionals and mental health professionals of the existence of these guidelines. Targeted strategies might include providing face-to-face briefings, distributing copies of the guidelines, offering ad hoc advice, working with media organisations to incorporate the guidelines into policies and practice, and providing regular follow-up and promotion. Specific dates of the year when there may be an increase in NSSI-related media content, which would be optimal times for dissemination of these guidelines, include Self-Injury Awareness Day (1 March), Mental Health Awareness Month (May), World Suicide Prevention Day (10 September) and World Mental Health Day (10 October). Mental health professionals and experts on NSSI who are asked to give interviews should consider providing copies of the guidelines (Appendix and supplementary Fig. 1) to media professionals directly and can offer general guidance based on research and sound clinical practice. NSSI experts interested in speaking to the media about NSSI may wish to pursue media training to increase comfort. On a final note, it is our hope that clinicians, researchers and those in academia and other teaching professions will carefully follow these guidelines not only when speaking to the media but also when presenting to audiences of all types (e.g. academics, continuing education, lay professionals and parents).

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.191.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Daniel Reidenberg, Dr Richard Graham, Dr Paula Braverman, Jane Bianchi and the ISSS membership for reviewing these guidelines and providing feedback. These guidelines were revised on the basis of their input.

Author contributions

N.J.W. conceptualised, designed and drafted the initial manuscript, the Appendix and overview of media guidelines section; S.P.L. drafted the rationale for media guidelines section and supplementary Fig. 1; J.W. drafted the recommendations for the social media section; H.T.S. drafted the recommendations for the section on disseminating these guidelines; B.A., M.S.A. and E.E.L.-R helped write the manuscript and provided important feedback regarding each media recommendation; and all authors reviewed and revised the manuscript, agreed on all media recommendations, approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of interest

J.W. reports personal fees from Instagram and from the Jed Foundation outside the submitted work.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.191.

Appendix

Recommendations for the media

The table below provides six specific elements to be avoided and included when reporting on non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in the media. Whenever possible, media coverage should follow all the recommendations, especially recommendations 1, 2 and 3.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.