Managing depression is the bread and butter of psychiatry. Depression is common, both on its own and comorbid with other disorders. It thus confers a significant disease burden and consequently, organisations have developed guidelines to inform management. However, the distillation of research findings and clinical wisdom has, at times, produced differing recommendations.Reference Gabriel, Stein, de Melo, Henrique Fontes-Mota, dos Santos and de Oliveira1 Usually, any lack of agreement has been attributed to the fact that depression is a heterogeneous ‘set’ of disorders and that many of its treatments are relatively non-specific. Further, the evidence is ever changing over time. Additionally, access, availability, cost and patient preferences make the real-world landscape of treating depression immensely variegated. Thus, although there is agreement that guidelines are necessary, the advice they offer is sometimes questioned with respect to real-world utility, largely because of perceived inconsistency.

This brief editorial compares the recommendations offered by two recently published guidelines: the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders (which we will call MDcpg2020)Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell2 and the National Institute for Health and Care (NICE) 2022 guidelines for depression (NG222).3

Diagnosis

Both sets of guidelines emphasise the importance of taking a more sophisticated approach than simply completing a checklist of symptoms, and attach importance to adopting a longitudinal perspective. Further, both draw on traditional classifications (DSM-5 and ICD-11) to define the boundaries of depression. However, NG222 divides depression according to severity – coalescing the older terms ‘subsyndromal’ and ‘mild’ to form ‘less severe’, and grouping ‘moderate’ and ‘severe’ as ‘more severe’. These relativistic terms (less and more) imply a continuum and lend the definition of depression a dimensional perspective, akin to that used in the MDcpg2020. At the same time, like its antipodean counterpart, NG222 also recognises subtypes such as psychotic depression.

For example, the MDcpg2020 views depression as a multifaceted entity that can be scaled according to severity (like NG222) but can also be subtyped depending on symptom profile, with the added sophistication of clustering symptoms into domains of activity, cognition and emotion (termed the ACE model). Both guidelines emphasise functional impairment as a critical determinant of help-seeking, interventions, long-term outcome and societal impact.

Treatment

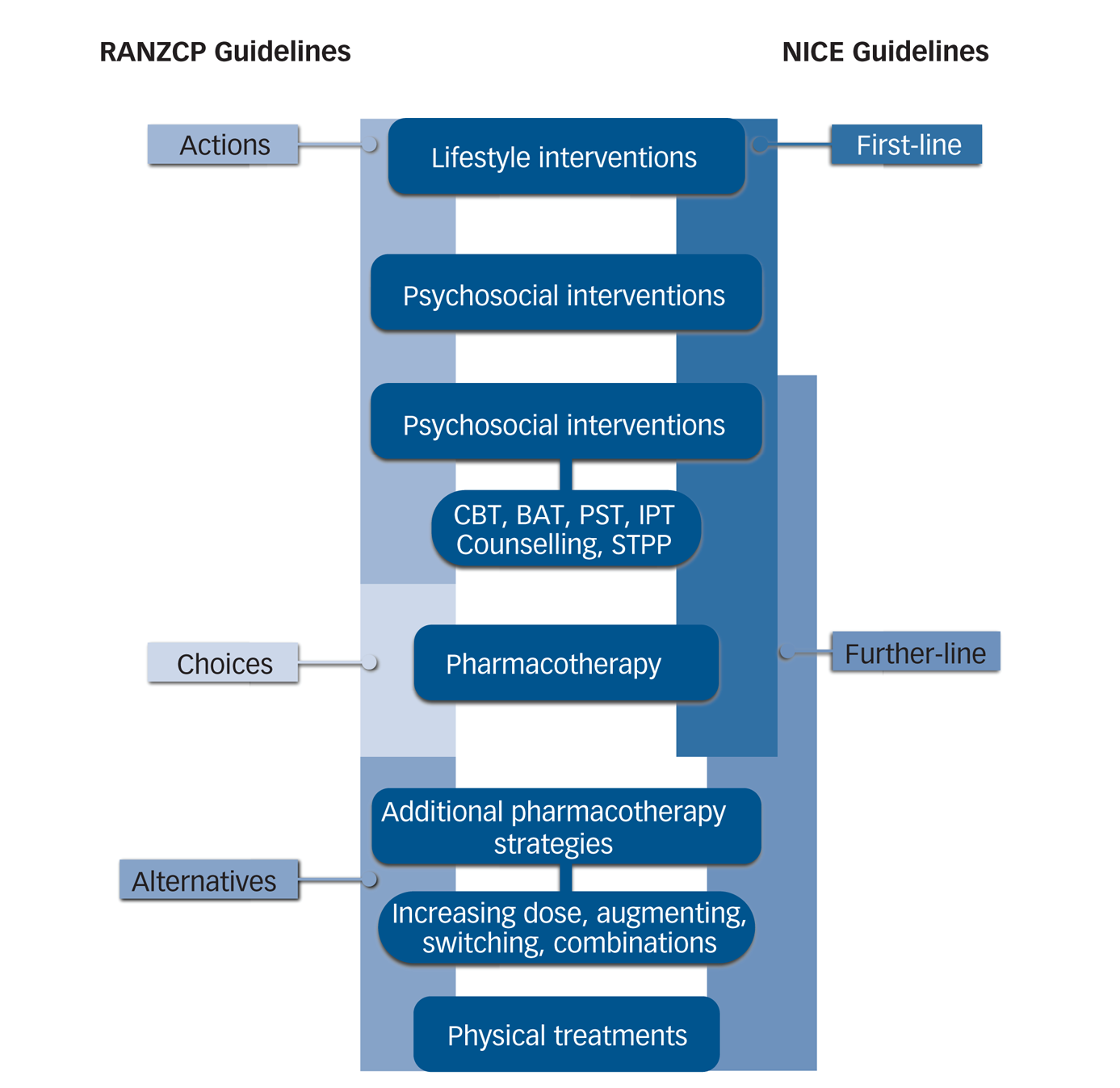

The majority of people with depression are treated in the community by general practitioners. Therefore, both guidelines focus on the management of the most common presentations of depression. Consequently, they prioritise lifestyle changes and advocate the use of psychological interventions and antidepressants for first-line management, before moving to more sophisticated strategies for further-line treatment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Comparison of recommended treatments and frameworks utilised in Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP)Reference Malhi, Bell, Bassett, Boyce, Bryant and Hazell2 and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)3 guidelines for managing depression.

Despite some subtle differences in the organisation of management (Actions, Choices and Alternatives versus first-line and further-line) the two sets of guidelines (MDcpg2020 and NG222) recommend the same interventions and sequence treatments in the same order. However, it is important to note that both guidelines allow flexibility within each schema, and management can commence at any point if indicated – for example, beginning with a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychological interventions for depression that is more severe, or administering electroconvulsive therapy for psychotic depression. CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; BAT, behavioural activation therapy; PST, problem-solving therapy; IPT, interpersonal therapy; Counselling, non-directive supportive therapy; STPP, short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy.

First-line treatment

NG222 sequences treatment options. These are considered separately for less severe and more severe depression. Like NG222, the MDcpg2020 suggests a broad range of first-line ‘Actions’, which include lifestyle changes and psychoeducation alongside psychological interventions. Within the latter, six kinds of psychological treatment are recommended on the basis that they meet the threshold for having ten or more randomised controlled trials (non-blinded) that demonstrate greater efficacy compared with controls (no treatment).

Within the MDcpg2020, management then proceeds to ‘Choices’, which comprise first-line pharmacotherapy, followed by ‘Alternatives’ recommending further pharmacological strategies and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). It is acknowledged that there are instances where medication may need to be commenced immediately with psychological treatments alongside, or both sets of interventions may need to be leapfrogged and an individual may require ECT immediately. Thus, all treatments (psychological interventions, psychoeducation, exercise, antidepressants and ECT) can be administered from the outset, dependent on the clinical presentation and patient preference. In other words, like NG222, all these treatments can be regarded as ‘first-line’, and once again there is good consensus between the two sets of guidelines as to what treatment can, and should, be prescribed when embarking on the management of depression.

NG222 recommends that if an individual has ‘not responded at all after 4 weeks of antidepressant treatment at a recognised therapeutic dose, or after 4–6 weeks for psychological therapy or combined medication and psychological therapy’, then non-response should be explored methodically. This includes a review of the diagnosis and treatment, while maintaining a positive and reassuring stance and a willingness to switch strategies. A similar versatile approach is advocated in the MDcpg2020, which also emphasises personalising treatment where possible, based on symptom profiles, treatment history and patient preference.

Further-line treatment

This straightforward term coined by NG222 addresses the multiple strategies that can be employed once initial attempts to obtain response are unsuccessful. Here, a detailed diagram (hot linked as ‘visual summary on further-line treatment’ in section 1.9.1)3 emphasises the need to address problems that may not seem to be directly pertinent to depression, such as personal, social or environmental factors, and advises that other illnesses (especially personality dysfunction) should also be considered as potential contributors to depression. This complex NG222 schema for management contains elements of the ‘medication, increase dose, augment, switch’ (MIDAS) approach described by the MDcpg2020. In both guidelines, it is emphasised that functional improvement can occur after any of the interventions and subsequent management strategies. For instance, treatments can be optimised using increases in dose where possible, augmenting and switching, and combinations can be trialled involving different kinds of intervention or for augmentation purposes.

These strategies address the needs of the majority of people with depression. However, also important are those who do not respond to treatment – described variably as having ‘difficult to treat’ or ‘treatment-resistant’ depression (TRD).Reference Malhi, Das, Mannie and Irwin4 This is not an uncommon outcome and is often the result of departing from best practice.Reference Strawbridge, McCrone, Ulrichsen, Zahn, Eberhard and Wasserman5 This is why NG222 also emphasises the importance of accurate diagnosis and re-evaluation of the diagnosis throughout the course of the illness: an important message that is promoted by both sets of guidelines.

Evidence

Guidelines rely on research evidence to formulate their recommendations. In the MDcpg2020 this was assessed using National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines (www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelinesforguidelines) and the merits of various treatments were determined on the strength of evidence overall. However, NG222 dug deeper still, and conducted detailed analyses of the available evidence to underpin its recommendations regarding clinical effectiveness. In addition, NG222 considered cost-effectiveness when making specific recommendations and factored both the accessibility and the ability to implement treatments into its considerations.

The extent to which available data have been interrogated, and the manner in which it has been synthesised within NG222, has to be commended. Naturally, there are many instances in which the evidence is incomplete or of poor quality. And here, rather than not making any recommendations whatsoever, both the MDcpg2020 and NG222 have opted to offer some clinical guidance. The MDcpg2020 does this more formally and distinguishes between evidence-based recommendations (EBRs) and consensus-based recommendations (CBRs). The latter were formulated when: (a) the existing intervention evidence base was absent, ambiguous or of doubtful clinical impact in the Australian and New Zealand context; and (b) the Mood Disorders Committee (based on collective clinical and research knowledge and experience) reached consensus on the clinical utility of the recommendations. CBRs acknowledge their limitations, but nevertheless provide useful advice on how to navigate less-established care options once more established options have been reasonably exhausted. At their core, the two sets of guidelines are evidence-based and pragmatically add to this evidentiary kernel, along with experience, cost and accessibility considerations, to enhance translation into practice. Consequently, the recommendations within the guidelines overlap considerably and this not only lends strength to their findings but provides greater confidence for clinicians choosing to base their treatment decisions on the advice in the guidelines.

Nevertheless, the use of CBRs highlights a key limitation of all clinical guidelines, namely, the paucity of empirical evidence to support recommendations for many key clinical questions or decisions. Thus, to produce more comprehensive guidelines that reflect the many clinical complexities of the illness, further research on real-world depression is needed. Steps towards this goal have already been taken by a recent European Brain Council initiative, which has identified treatment gaps between ‘best’ and ‘current’ practice.Reference Strawbridge, McCrone, Ulrichsen, Zahn, Eberhard and Wasserman5 Examining practices in six European countries, researchers found gaps in the detection of depression and provision of treatment, especially with respect to follow-up and access to specialist care. Consequently, they have formulated a comprehensive set of recommendations to better meet patient needs.

Conclusions

Overall, the agreement between the MDcpg2020 and NG222 yields several key guiding principles with respect to how depression should be managed. These include advocating for robust diagnosis and ongoing re-evaluation of this throughout management. They prioritise the use of psychological and lifestyle interventions where possible, and emphasise the adoption of a flexible style of management within the recommended schema of treatments and therapeutic strategies to personalise care.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

G.S.M. and E.B. conducted the initial research and drafting of this piece. All other authors contributed to the writing and editing and approve of the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

G.S.M. has received grant or research support from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Australian Rotary Health, NSW Health, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Ramsay Research and Teaching Fund, Elsevier, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Servier; and has been a consultant for AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Servier. P.B. has received research support from the NHMRC, speaker fees from Servier, Janssen and the Australian Medical Forum, educational support from Servier and Lundbeck, has been a consultant for Servier, served on an advisory board for Lundbeck, has served as Data and Safety Monitoring Committee Chair for Douglas Pharmaceuticals and has served on the Medicare Schedule Review Taskforce (Psychiatry Clinical Committee). R.B. has received grant support in the past 5 years from the NHMRC, the Australian Research Council, TAL Insurance, and support for travel for advisory meetings to the World Health Organization. M.H. has received grant or research support in the past 5 years from the NHMRC, Medical Research Future Fund, Ramsay Health Research Foundation, Boehringer-Ingleheim, Douglas, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Lyndra, Otsuka, Praxis and Servier; and has been a consultant for Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka and Servier; and has served on the Medicare Schedule Review Taskforce (Psychiatry Clinical Committee). R.M. has received support for travel to education meetings from Servier and Lundbeck, speaker fees from Servier and Committee fees from Janssen. R.P. has received support for travel to educational meetings from Servier and Lundbeck and uses software for research at no cost from Scientific Brain Training Pro. G.M. has received grant support in the past 5 years from the NHMRC, the Mental Illness Research Fund, Victorian Medical Research Acceleration Fund, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Readiness, SiSU Wellness and the Barbara Dicker Foundation. D.B. has received funding to host webinars by Lundbeck. A.B.S. has shares/options in Baycrest Biotechnology Pty Ltd (pharmacogenetics company) and Greenfield Medicinal Cannabis, has received speaking honoraria from Servier, Lundbeck and Otsuka Australia.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.