Eating behaviours reflect our relationship with food and behavioural responses to food cues in the environment.Reference Russell and Russell1 Eating behaviours develop early and track according to distinct trajectories.Reference Herle, De Stavola, Hübel, Santos Ferreira, Abdulkadir and Yilmaz2 Although childhood eating behaviours have typically been studied in the context of obesity,Reference Llewellyn and Wardle3 their role in the development of eating disorders in adolescence has received little attention. Importantly, in addition to overeating and undereating, food fussiness (the tendency to eat only certain foods and to refuse to try new foods) is common during childhood,Reference Herle, De Stavola, Hübel, Santos Ferreira, Abdulkadir and Yilmaz2 and might be a precursor to adolescent dieting, a previously suggested risk factor for anorexia nervosa.Reference Thornton, Trace, Brownley, Algars, Mazzeo and Bergin4 The aetiology of eating disorders remains poorly understood and primary prevention of eating disorders, especially in children, is in need of improvement.Reference Le, Barendregt, Hay and Mihalopoulos5 A study following 800 children from 6 to 22 years highlighted that conflicts and struggles around meals in childhood were associated with higher risk for anorexia nervosa in adolescence and young adulthood, whereas childhood undereating was associated with later bulimia nervosa.Reference Kotler, Cohen, Davies, Pine and Walsh6 This study was limited by its relatively small sample size, low number of eating disorder cases and focus on diagnosed eating disorders excluding eating disorder behaviours, which may be prodromal expressions of eating disorder risk. Additionally, data from the longitudinal 1970 National Child Development Study showed that infant feeding problems and childhood undereating were risk factors for adult anorexia nervosa at age 30 years.Reference Nicholls and Viner7 However, in contrast to these previous studies, infant and childhood eating behaviours were not associated with adult bulimic or compulsive eating.Reference Nicholls, Statham, Costa, Micali and Viner8 These studies, however, might have benefited from a more comprehensive assessment of childhood eating. We have recently shown a longitudinal relationship between childhood growth and eating disorders.Reference Yilmaz, Gottfredson, Zerwas, Bulik and Micali9 Further, we have described longitudinal trajectories of eating behaviour in childhood and their association with body mass index (BMI) at age 11 years.Reference Herle, De Stavola, Hübel, Santos Ferreira, Abdulkadir and Yilmaz2 In this study, we aimed to extend this work by establishing the associations between eating behaviour trajectories during the first ten years of life and eating disorder behaviours and diagnoses in adolescence, leveraging data from a large UK-based birth cohort. We hypothesised that continuity would be observed from eating behaviours in childhood to eating disorder behaviours and disorders in adolescence. Specifically, overeating during childhood would be associated with increased risk for binge eating, purging, binge eating disorder (BED) and purging disorder in adolescence. Conversely, we hypothesised that undereating and fussy eating would be associated with greater risk for fasting, excessive exercise and anorexia nervosa in adolescence.

Method

Ethics

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) Ethics and Law Committee and the local research ethics committees.

Study population

Data were from the ALSPAC, a population-based longitudinal cohort of mothers and their children born in the southwest of England.Reference Fraser, Macdonald-Wallis, Tilling, Boyd, Golding and Smith10,Reference Boyd, Golding, Macleod, Lawlor, Fraser and Henderson11 All pregnant women expected to give birth between 1 April 1991 and 31 December 1992 were invited to enrol in the study, providing informed written consent. A total of 14 451 pregnant women opted to take part; by 1 year, 13 988 children were alive. One sibling per set of multiple births (N = 203 sets) was randomly selected from these analyses to guarantee independence of participants. Please note that the study website contains details of all the data that is available through a fully searchable data dictionary and variable search tool. (www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/our-data).

Outcomes

Eating disorder diagnoses and behaviours

Binge eating, purging, fasting and excessive exercise were obtained by self-report at age 16 years. We adapted questionnaire items from the Youth Risk Behaviour Surveillance System,Reference Kann, Warren, Harris, Collins, Williams and Ross12 which has previously been validated in a population-based study.Reference Field, Taylor, Celio and Colditz13 Binge eating was defined as eating a large amount of food at least once a week and having a feeling of loss of control during that episode. To assess purging behaviour, participants indicated if they used of laxatives or self-induced vomiting to lose weight or avoid gaining weight. Fasting was described as not eating at all for at least a day, to lose weight or avoid gaining weight. Participants who indicated that they exercised for weight loss purposes, felt guilty about missing exercise and found it hard to meet other obligations, such as schoolwork, because of their exercise regime were coded as engaging in excessive exercise. Eating disorder diagnoses according to DSM-5 criteria (i.e. anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, BED and purging disorder) were obtained as described previously.Reference Micali, Solmi, Horton, Crosby, Eddy and Calzo14

Analyses were restricted to adolescent eating disorder diagnoses and behaviours at age 16 years to balance the loss of participants at later ages (18 years) and the low prevalence of the outcomes at earlier ages (age 14 years).

Exposures

Trajectories of childhood eating behaviours

Trajectories of overeating, undereating and fussy eating were included from repeated measures of parent-reported child eating behaviours available at eight time points (around the ages of 1.3, 2, 3.2, 4.6, 5.5, 6.9, 8.7 and 9.6 years), (see Herle et al. for detailsReference Herle, De Stavola, Hübel, Santos Ferreira, Abdulkadir and Yilmaz2). Parents indicated how worried they were about their child's overeating and undereating. Fussy eating was rated across three questions: ‘being choosy’, ‘refusing food’ and ‘general feeding difficulties’. Response options for the five items were ‘did not happen’, ‘happened, but not worried’ and ‘a bit/greatly worried’. Trajectories were derived using latent class growth analyses with children that had data on at least one time point (n = 12 002). Analyses included children with data on child eating behaviours trajectories and at least one of the outcomes at age 16 years (n = 4760).

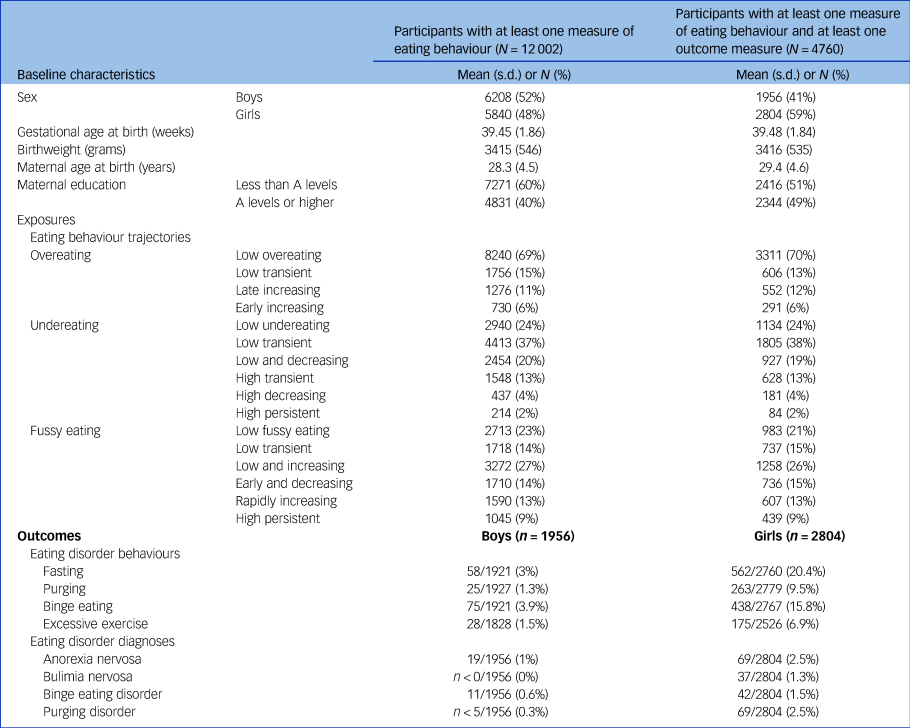

Overeating trajectories included ‘low overeating’ (children described as having no overeating in childhood, n = 3311, 70%), ‘low transient overeating’ (children with some degree of overeating during the first 5 years, which subsided by 9.6 years, n = 606, 13%), ‘late increasing overeating’ (children with low levels of overeating until age 5 years and increasing levels from this age onwards, n = 552, 12%) and ‘early increasing overeating’ (children with an early onset of overeating which progressively increased over time, n = 291, 6%).

Undereating trajectories included ‘low undereating’ (children with no undereating, n = 1134, 24%), ‘low transient undereating’ (children with some undereating, which decreased to no undereating by 4.6 years, n = 1805, 38%), ‘low and decreasing undereating’ (children with some undereating during childhood, which completely subsided by 9.6 years, n = 927, 19%), ‘high transient undereating’ (children with high levels of undereating at 1.3 years, which rapidly decreased by 5.5 years, n = 628, 13%), ‘high decreasing undereating’ (children with high levels of undereating, which slowly decreased to no undereating by 9.6 years, n = 181, 4%) and ‘high persistent undereating’ (children who were persistently undereating across childhood, n = 82, 2%).

Fussy eating was represented in six trajectories: ‘low fussy eating’ (children characterised by no fussy eating, n = 983, 21%), ‘low transient fussy eating’ (low levels of fussy eating in the first 5 years of life, which decreased to no fussy eating by 9.6 years, n = 737, 15%), ‘low and increasing fussy eating’ (characterised by a low level of fussy eating that slowly increased with time, n = 1258, 26%), ‘early and decreasing fussy eating’ (high levels of fussy eating at 1.3 years, which decreased gradually, n = 736, 15%), ‘rapidly increasing fussy eating’ (low levels of fussy eating at 1.3 years which increased rapidly with age, n = 607, 13%) and ‘high persistent fussy eating’ (children who were fussy eaters throughout the period assessed, n = 439, 9%).

Groups are illustrated in Supplementary Figs 1–3 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.174.

Covariates

The following covariates were included to control for confounding of the association between the exposures and outcomes: maternal education status (A levels or higher, lower than A levels; A levels are needed to enrol in university in the UK), to proxy socioeconomic status of the family; maternal age at birth and size at birth (gestational age and birth weight), as well as assigned sex at birth.

Statistical methods

We estimated the association between the eating behaviour trajectories of overeating, undereating and fussy eating and eating disorder outcomes during adolescence, using multivariable logistic regression models. The results are presented in two ways: estimated mean probabilities of outcomes per class, averaged over the distribution of the confounders (marginal effects); and estimated risk differences relative to the reference group, i.e. the estimated difference in risk of eating disorder behaviours and diagnoses for each group of eating behaviours, relative to the reference group. In addition, we also report baseline risks of the outcomes in these reference groups, averaged over the distribution of the confounders, which indicate the risk of endorsing disordered eating outcomes and eating disorder diagnoses for adolescents classified with low levels of child overeating, undereating and fussy eating. As commonly observed in longitudinal cohorts, data are subject to loss to follow-up. We assumed outcome data were missing at random, conditionally on the variables included in the models, which are associated with drop-out: maternal education and maternal age. Eating disorder behaviours and diagnoses tend to be more common in girls. Hence, we repeated regression analyses in girls only (Supplementary Tables 1a–c). Regression analyses were conducted in Stata version 15 for Windows. Two-sided tests were used to assess significance with Bonferroni corrections implemented, dividing 0.05 by the number of comparisons for each eating behaviour. This lead to P ≤ 0.02 for overeating (0.05 divided by 3), and P ≤ 0.01 for undereating and fussy eating (0.05 divided by 5).

Results

There were no cases of bulimia nervosa in boys and few (<0.5%) cases of purging disorder in either boys or girls, hence these were dropped from our analyses (Table 1).

Table 1 Distribution of baseline variables by completeness of eating behaviours and outcome data

Associations between eating behaviour trajectories and eating disorder behaviours and diagnoses

Overeating

Children in the low overeating reference trajectory had an estimated baseline risk of 10% (95% CI, 9 to 11) for binge eating at 16 years, 2% (95% CI 0 to 5) for purging and 1% (95% CI 0 to 1) met diagnostic criteria for BED (Supplementary Fig. 4). Children with late increasing overeating had a 6% increased risk of engaging in binge eating compared with the reference low overeating group (risk difference, 5%; 95% CI 2 to 8). Children with early increasing overeating had a 7% greater risk of binge eating (risk difference, 7%; 95% CI 2 to 11). Those with late increasing overeating had a 1% increase in risk of BED (risk difference, 1%; 95% CI 0 to 3) (see Table 2). There was no association between overeating trajectories and purging.

Table 2 Estimated baseline risks and risk differences by overeating trajectories and outcomes at age 16 years, adjusted for sex at birth, gestational age, birth weight, maternal age and maternal education

Associations between overeating trajectories and purging disorder were not adjusted for sex because of collinearity, as purging disorder was not common in boys (<0.5%).

a. Reference group.

* Below P-value after Bonferroni correction by the number of comparisons, 0.02.

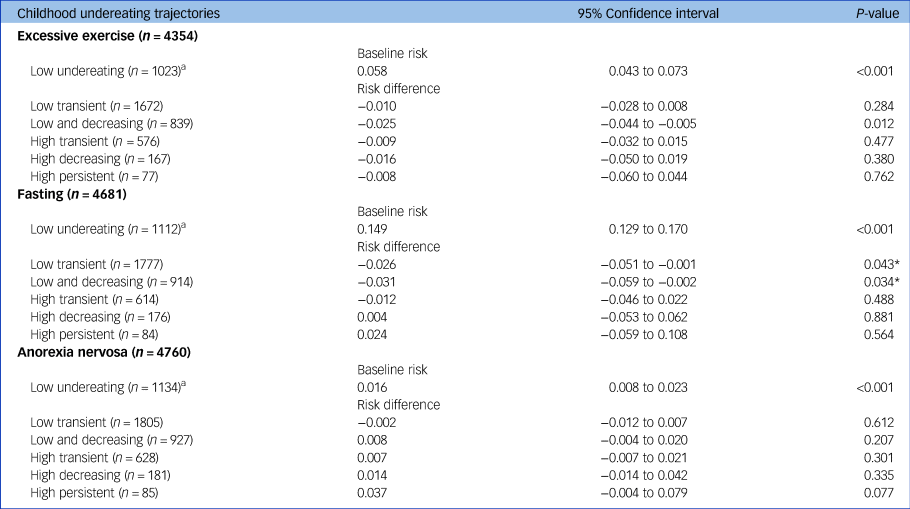

Undereating

Children in the reference group had an estimated baseline risk of 6% (95% CI 4 to 7) for excessive exercise, 15% (95% CI 13 to 17) for fasting and 2% (95% CI 1 to 2) of anorexia nervosa. In comparison, low transient and low, but slowly decreasing, undereating was associated with a 3% lower risk of fasting (risk difference, −3%; 95% CI −5 to 0 and risk difference, −3; 95% CI −6 to 0, respectively) and purging (both groups; risk difference, −3%; 95% CI −5 to −1) compared with the reference group with no undereating at all (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 5). In addition, children with low and decreasing levels of undereating had a 2% risk reduction for excessive exercise (risk difference, −3%; 95% CI −4 to −1). There was no association between undereating trajectories and anorexia nervosa. However, when investigating girls only, children in the persistent high undereating children had a 6% increased risk of meeting anorexia nervosa diagnostic criteria compared with the reference group (risk difference, 6%; 95% CI 0 to 12) (Supplementary Table 1b).

Table 3 Estimated baseline risks and risk differences by undereating trajectories and outcomes age 16 years, adjusted for sex at birth, gestational age, birth weight, maternal age and maternal education

Associations with excessive exercise were not adjusted for sex and maternal education because of collinearity.

a. Reference group.

* P-value exceeds cut-off for threshold after Bonferroni correction by the number of comparisons, 0.01.

Fussy eating

Children in the reference group had an estimated baseline risk of 6% (95% CI 4 to 7) excessive exercising, 15% (95% CI 13 to 17) fasting and 1% (95% CI 0 to 2) of anorexia nervosa. Children with high persistent fussy eating had a 2% risk increase for anorexia nervosa compared with the children never reported to be fussy eaters (risk difference, 2%; 95% CI 0 to 0.4%) (Supplementary Fig. 6, Table 4). Similarly, the children who were fussy eaters only in early life (‘Early and decreasing’) had 2% increased risk of anorexia nervosa (risk difference, 2%; 95% CI 1 to 4%) compared with the low fussy eating reference group. There were no associations between fussy eating trajectories and excessive exercise.

Table 4 Estimated baseline risks and risk differences by fussy eating trajectories and outcomes age 16 years, adjusted for sex at birth, gestational age, birth weight, maternal age and maternal education

a. Reference group.

* P-value lower cut-off for threshold after Bonferroni correction by the number of comparisons, 0.01.

** P-value exceeds cut-off for threshold after Bonferroni correction by the number of comparisons, 0.01.

Sensitivity analyses

Given the possibility that the associations between high persistent undereating, high persistent fussy eating and later anorexia nervosa might be driven by children who were both persistent undereaters and fussy eaters, we performed sensitivity analyses to investigate the overlap between girls with persistent undereating and persistent fussy eating. However, among the 69 girls meeting criteria for anorexia nervosa, only four fell into both the persistent undereating and persistent fussy eating group. This indicates that both eating behaviours may have a unique association with anorexia nervosa.

Discussion

We have conducted the most comprehensive investigation of the association between child eating behaviours and eating disorder behaviours and diagnoses in adolescence. In line with our hypotheses, overeating during childhood was associated with increased risk for binge eating and BED at 16 years. Children with elevated overeating were found to have 6–7% greater risk of engaging in binge eating than children in the persistently low group, relative to the baseline risk of 10%. In addition, those with an increase in overeating in mid-late childhood had a 1% greater probability of BED compared with the reference group, suggesting that overeating behaviour linked to later BED might start in mid-childhood at about age 5 years. Results highlight how increasing rates of childhood overeating could foreshadow later binge eating, and support the results from smaller longitudinal studies indicating that eating in absence of hunger in childhood is associated with greater binge eating at 15 years.Reference Balantekin, Birch and Savage15 Additional research, using molecular genetic approaches, proposed that genetic variants associated with BMI were also associated with adolescent binge eating, suggesting a shared genetic aetiology between overeating and binge eating.Reference Micali, Field, Treasure and Evans16

Low levels of undereating were associated with lower risk of fasting and excessive exercise at age 16 years. Low levels of undereating might be interpreted as a sign of a healthy appetite in early life, which could act as a protective factor, reducing the risk of later anorexia nervosa, fasting, purging and excessive exercise. In accordance, previous research has suggested that higher BMI at 10 years was associated with body dissatisfaction and dieting at age 14 years.Reference Micali, De Stavola, Ploubidis, Simonoff, Treasure and Field17 In contrast to our hypotheses, we found no associations between persistent undereating and later eating disorder behaviours or diagnoses; this is likely because of the small number of children and this is reflected in the wide confidence interval estimates found in the results. In comparison, when repeating the analyses in girls only, there was an indication that persistent undereating was associated with a 6% increase in risk for anorexia nervosa relative to baseline risk of 1%. However, because of the reduced sample, the persistent undereating trajectory only included 54 girls and the confidence intervals were wide (from 0 to 13%). Previous longitudinal research has suggested that early feeding problems and undereating in childhood are linked to adolescent anorexia nervosa.Reference Kotler, Cohen, Davies, Pine and Walsh6,Reference Nicholls and Viner7 In addition, adolescents with eating disorders have been found to have different patterns of growth in the first 12 years of life, with patients with anorexia nervosa showing consistent premorbid low BMI.Reference Yilmaz, Gottfredson, Zerwas, Bulik and Micali18 Similar to the association between overeating, binge eating and obesity, shared genetic vulnerability might contribute to the association between consistent levels of undereating in childhood and risk for anorexia nervosa.

In line with our hypotheses, early life and persistent food fussiness was associated with a 2% risk increase in anorexia nervosa compared with no fussy eating (baseline risk 1%). Fussy eating in childhood might, in some cases, be an early manifestation of later anorexia nervosa. However, the shared aetiology between fussy eating and disordered eating is unknown. The newly described diagnosis of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)19 is of interest. ARFID is characterised by severe restriction and lack of interest in food,Reference Bryant-Waugh20 resulting in failure to meet appropriate energy and/or nutritional needs. The persistent fussy eating group might include children with ARFID, suggesting a potential association between childhood ARFID and adolescent anorexia nervosa. ARFID in childhood has been suggested as a risk factor for adolescent anorexia nervosa,Reference Norris, Robinson, Obeid, Harrison, Spettigue and Henderson21 and more longitudinal research is needed. Severe and persistent fussy eating can be very stressful for families, and parents, often understandably, respond by pressuring their child to eat more or offering treats as rewards to entice their child to eat.Reference Harris, Fildes, Mallan and Llewellyn22 Parental pressure to eat has been associated with weight and shape concerns,Reference Agras, Bryson, Hammer and Kraemer23 and to fasting in adolescence,Reference Loth, MacLehose, Fulkerson, Crow and Neumark-Sztainer24 which might unintentionally steer fussy children toward more extreme behaviours. However, it is important to note that parent–child conflicts in adolescence are more likely to be the consequence of disordered eating rather than the cause.Reference Spanos, Klump, Burt, Mcgue and Iacono25 Our results presented here provide support for the hypothesis that persistent levels of child fussy eating might be a contributing factor or potentially an early manifestation of adolescent anorexia nervosa. However, the mechanism behind this observation is unknown.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the largest and most comprehensive investigation to examine the prospective association between childhood eating behaviours and adolescent eating disorder behaviours and diagnoses. Data were from a population-based cohort, and longitudinal latent trajectories were used as exposures to acknowledge the heterogeneity of childhood eating behaviours, superseding the few previous longitudinal studies in this field. In addition, diagnoses of eating disorders were derived from a combination of self- and parental report. As commonly observed in longitudinal cohort studies, participants tend to drop out as time goes on. This loss of follow-up has been associated with socioeconomic position of the participantsReference Howe, Cole, Lau, Napravnik and Eron26 and their families, reducing the generalisability of the findings. Hence, we included maternal education and maternal age at birth in the analyses. Eating disorder behaviours and diagnoses were not very common, especially in boys, leading to low statistical power. Questionnaires to assess eating disorder diagnoses and behaviours tend to be geared toward girls, and separate assessments with tools specifically for boys would have been beneficial.Reference Calzo, Horton, Sonneville, Swanson, Crosby and Micali27 Additionally, we were not able to estimate the association between eating behaviour trajectories and adolescent ARFID, as the study and measures to assess eating disorders were developed before the definition of ARFID. A new psychometric tool for ARFID is now available and can be used in future observational studies.Reference Bryant-Waugh, Micali, Cooke, Lawson, Eddy and Thomas28

Implications

Adolescent eating disorder behaviours and eating disorders are complex and influenced by interactions of biological, behavioural and environmental factors.Reference Culbert, Racine and Klump29 Our results support the hypothesis that there is continuity between early life eating behaviours and later eating disorder behaviours and eating disorders. This notion has important implications for future preventive strategies. Findings suggest that identifying children with specific eating behaviours might be a promising approach for targeted intervention to prevent progression to disordered eating and eating disorders in adolescence. Previous trials highlighted that childhood eating behaviours are modifiable through interventions targeting parental feeding and education.Reference Magarey, Mauch, Mallan, Perry, Elovaris and Meedeniya30 However, these intervention studies focus on the development of healthy eating behaviours in the context of obesity prevention and not eating disorders, and may have unintended consequences. For example, it has been observed that parental pressure to eat can lead to increased food refusal.Reference Wright, Parkinson and Drewett31 Importantly, recent evidence suggests that family-based treatment intervention for weight loss might also positively influence disordered eating behaviours such as binge eating in adolescents with obesity.Reference Hayes, Fitzsimmons-Craft, Karam, Jakubiak, Brown and Wilfley32 Our results suggest that children who show high levels of fussy eating in early childhood might be at increased risk of developing anorexia nervosa, but the mechanisms behind this association are unknown and need to be further explored.

In conclusion, the results from this study extend the previous longitudinal studies and support the hypothesis of continuity from childhood eating behaviours to eating disorder behaviours and disorders in adolescence, particularly for childhood overeating and later binge eating, and for childhood fussy eating and later anorexia nervosa. There was an indication of an association between persistent undereating and anorexia nervosa in girls only. Our observations pave the way for improved understanding of risk pathways to eating disorders, including the role of early phenotypic manifestations, and exploration of genetic risk. Future investigations should explore protective factors that buffer children who display high persisting levels of overeating and fussy eating from developing eating disorder behaviours or eating disorders later on.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.174.

Funding

This work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council and the Medical Research Foundation (ref: MR/R004803/1). The UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome (grant 102215/2/13/2) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. A comprehensive list of grants funding is available on the ALSPAC website (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf). C.M.B. acknowledges funding from the Swedish Research Council (VR Dnr: 538-2013-8864). D.S.F. works in a unit that receives funds from the University of Bristol and the UK Medical Research Council (MC_UU_00011/6). The funders were not involved in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.