Violence and aggression occur frequently in mental health settings Reference Bowers, Stewart, Papadopoulos, Dack, Ross and Khanom1 and are associated with significant individual costs to those assaulted, as well as substantial economic costs to the health service. 2 Serious patient safety concerns have been reported about the use of physical restraint to manage violence and aggression in these settings, including death as a result of positional asphyxia Reference Paterson, Bradley, Stark, Saddler, Leadbetter and Allen3 and symptoms of post-traumatic stress. Reference Bonner, Lowe, Rawcliffe and Wellman4 Such serious consequences have resulted in the prioritisation of non-physical approaches, such as de-escalation techniques, in both US Reference Richmond, Berlin, Fishkind, Holloman, Zeller and Wilson5 and UK violence and aggression management policy. 6 De-escalation techniques aim to stop the escalation of aggression to either violence or the use of physically restrictive practices via a range of psychosocial techniques. Reference Bowers, James, Quirk, Wright, Williams and Stewart7 These typically involve the use of non-provocative verbal and non-verbal clinician communication to negotiate a mutually agreeable solution to the aggressor’s concerns. Reference Price and Baker8 Evidence of wide variation in skill levels among staff Reference Nau, Halfens, Needham and Dassen9 may be a barrier to the effectiveness of these techniques, and suggests a potentially influential role for training in addressing skills deficits and their associated harms. Although training in de-escalation techniques is now a key component of mandatory conflict resolution training for National Health Service (NHS) mental health staff, 10 little is known about its effectiveness in terms of improved performance and reduction of harm associated with violence and aggression. To address this important evidence gap, this review systematically evaluates current evidence for de-escalation techniques training.

To inform a robust evaluation of the evidence, it is important to first develop a conceptual understanding of training function. Effective training has previously been conceptualised as a series of cognitive (knowledge, self-awareness, self-regulation), affective (enhanced motivation, self-efficacy) and skills-based improvements, combined with a transfer of learning to improved job performance. Reference Kraiger, Ford and Salas11 This review will use this framework to evaluate the effectiveness of de-escalation techniques training. The literature suggests that staff de-escalation techniques may be influenced either directly, through skills-teaching, Reference Beech and Leather12 or indirectly, through modification of staff attitudes to patients, the nature of their mental health problems and their attributions as to the causes of aggression. Reference Hahn, Needham and Abderhalden13,Reference Endley and Berry14 Both approaches are thought to improve interpersonal styles when faced with aggression, reducing the risk of assault (Table 1). This review will incorporate the evaluation of both approaches, which can be delivered either individually or in combination.

Table 1 De-escalation techniques training – mode of action

| Training approach | Cognitive outcomes | Affective outcomes | Behaviour change | Clinical outcome | Organisational outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct skills teaching |

Knowledge of behavioural skills and strategies for emotional regulation |

Increased

confidence/ self-efficacy |

Enhanced interpersonal style when managing aggressive behaviour |

Reduced assaults | Reduced expenditure |

| Emotionally regulated when faced with aggressive behaviour |

Reduced containment usage |

||||

| Modification of staff attitudes |

Accurate understanding of the nature of patients’ problems and the causes of the aggression |

Reduced

negative emotions (fear/anger/blame) |

Reduced behaviours likely to provoke escalations (avoidance/hostility/criticism) |

Reduced escalations | Reduced expenditure |

| Increased empathy | Understands patient needs during escalation |

Reduced assaults | |||

| More compassionate responses to escalation |

Reduced containment usage |

||||

For the purposes of this review, we have adopted the following definitions: moderators – baseline variables that may affect the relationship between independent and dependent variables; grey literature – literature published outside of conventional academic channels, i.e. outside of electronic databases and online journals; containment – procedures aiming to safely manage disturbed behaviour when verbal interventions have failed, such as PRN medicines and physical restraint.

In addition to evaluating the effectiveness of de-escalation techniques training through direct skills-teaching and/or staff attitude modification, we identified (1) potential moderators of training effectiveness and (2) evidence of the acceptability of training interventions.

Method

Search strategy

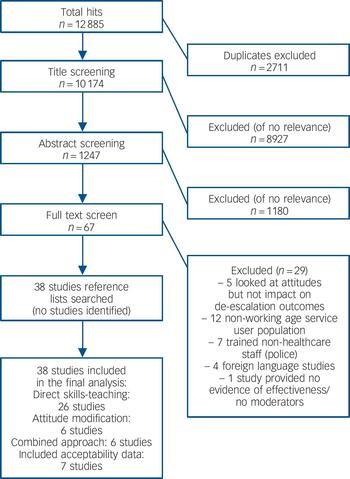

Search terms were developed to answer the review objectives using the key concepts of mental health, staff attitudes, de-escalation techniques, training and violence (full strategy available upon request). The search strategy was subject to a preliminary validity check and then applied to: AMED, ASSIA, Social Services Abstracts, British Nursing Index (and archive), EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library (all sources), SSCI + SCIEXPANDED, CINAHL, and metaRegister of Controlled Trials; all from database inception to August 2014. After eligibility screening and obtaining the final sample of included studies, each study’s reference list was screened to identify further studies that had not been identified (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Search results.

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria

Population

-

(1) Healthcare staff working with adult populations with mental health problems aged 18–65 years.

Intervention

-

(1) Training with a de-escalation techniques component.

-

(2) Training aiming to reduce violence and aggression AND/OR improve de-escalation skills through modification of staff attitudes.

Design

-

(1) Quantitative studies evaluating training effectiveness and/or moderators of effectiveness.

-

(2) Qualitative studies examining acceptability of training interventions.

Outcomes

-

(a) Cognitive, affective, skills-based, clinical and organisational outcomes of training (as per Table 1).

Exclusion criteria

Population

-

(1) Training of non-healthcare staff (police, security staff).

-

(2) Non-working age patients.

-

(3) Intellectual disabilities services.

Intervention

-

(1) Training without de-escalation techniques or attitudinal component.

Design

-

(1) Non-primary research (reviews, opinion, discussion papers).

-

(2) Grey literature.

Outcomes

-

(1) Implementation studies providing no data on effectiveness, moderators or acceptability.

-

(2) Evaluations aiming to modify staff attitudes to aggression without investigating the resultant impact on de-escalation performance or clinical outcomes.

Eligibility screening

Duplicates were removed and screening was conducted on titles and abstracts and full text according to the eligibility criteria. Selection of full text articles was independently verified by two researchers.

Data extraction

Extracted data were assigned to five categories of outcome: cognitive, affective, skills-based, and clinical and organisational outcomes (Table 1). Moderators were extracted at staff level, patient level, organisational level, environmental level and training level (characteristics of training). Further data extracted included acceptability of interventions, contextual information about the design and delivery of interventions, and design of the studies. Verification of extractions was completed independently by two researchers. The team met and potential errors/disagreements were resolved through team consensus (data extraction tables are available on request).

Quality appraisal

The methodological quality of included quantitative studies was appraised using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. Reference Thomas, Ciliska, Dobbins and Micucci15 This tool rates quality in six domains: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, study withdrawals/dropouts, and demonstrates acceptable construct validity and inter-rater reliability (κ = between 0.61 and 0.74). Reference Thomas, Ciliska, Dobbins and Micucci15 Quality assessment decisions were independently verified by two researchers who met and potential errors/disagreements were discussed and resolved through third-party consensus. Quality of moderator analyses was assessed using four key criteria suitable for use with non-randomised studies. These were: the validity of tools used to detect moderators; the number of potential moderators tested (measuring fewer variables may enhance the reliability of predictor effects); hypothesis of predictor effects determined a priori (i.e. findings are confirmatory rather than exploratory); and analysis involves direct testing of the relationship between the predictor and the independent variable. Reference Knopp, Knowles, Bee, Lovell and Bower16 Quality of qualitative acceptability data was assessed using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ), a checklist for appraisal of qualitative studies across three domains: (1) research team and reflexivity, (2) study design, and (3) data analysis and reporting. Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig17

Data synthesis

Qualitative and quantitative data were analysed separately. An initial scoping review of the available evidence revealed substantial heterogeneity of study designs and, with such small numbers of eligible studies returned for each outcome category, conducting a meaningful meta-analysis was impossible. All quantitative data were tabulated according to key training outcomes (cognitive, affective, skills-based, and clinical and organisational outcomes). Standardised effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated for papers reporting data appropriately. Effect sizes were not calculated when no means and s.d.’s were reported or when the product of a statistical test was omitted. There were insufficient qualitative data for formal qualitative data analysis. The few open-ended comments about the training that were identified were organised into themes and agreed by the review team. Quantitative and qualitative data were then synthesised into narratives for each of the relevant outcomes.

Results

Search results

The search identified 38 relevant studies from 10 174 hits (Fig. 1). Twenty-six studies were focused on direct skills-teaching, six studies aimed to influence either de-escalation performance or reduce violence and aggression through modification of staff attitudes, and six used a combination of both approaches (Table DS1, online supplement). There were 23 uncontrolled cohort studies, 12 controlled cohort studies and 3 case control studies (Table DS1). No randomised control trials (RCTs), the gold standard for intervention effectiveness, were identified. Studies were predominantly conducted in the USA (n = 10) or the UK (n = 14). Samples were biased towards unqualified staff (64% unqualified v. 36% qualified) and student nurse populations (39% of the total trained participants). Seven studies provided a rudimentary qualitative evaluation of training acceptability. Reference Smoot and Gonzales18–Reference Goodykoontz and Herrick24

Heterogeneity of intervention intensity and content

Potentially important variations were identified in training intensity and content. Ten studies provided high-intensity training (defined as >1 week’s formal training), 11 studies provided medium-intensity training (defined as >1 day’s and <1 week’s formal training) and 9 studies provided low-intensity training (defined as <1 day’s formal training) (Table DS1). Level of intensity was unclear due to inadequate reporting in three studies and because of the informal nature of the training in a further five studies (Table DS1). Second, there was variation both in the de-escalation techniques taught and the amount and content of adjunct training delivered. A full description of these differences is provided in Table 3 and online Table DS2.

Table 3 De-escalation components of interventions

×, training component present.

a. Specific interpersonal strategies included: problem clarification, positive reinforcement, offering alternatives, shared problem solving, and confirming messages.

b. Cognitive-affective components included: attitudes, empathy, emotional regulation, self-awareness, and confidence.

Quality appraisal

Overall the quality of the studies was moderate to weak. One study was rated as strong, 18 as moderate and 19 as weak (Table 2). Judgement of the representativeness of study samples was, in many cases, problematic. Often, studies failed to report how participants, wards or hospitals were recruited and only 11/37 studies reported response rates. Of those, seven had rates of uptake between 80 and 100%, although none provided data on non-respondents (Table 2). Although a number of the studies either reported potentially confounding differences between intervention and control groups at baseline or between service configuration or delivery models pre-and-post-intervention, Reference Nau, Halfens, Needham and Dassen9,Reference Smoot and Gonzales18,Reference Laker, Gray and Flach25–Reference Sjostrom, Eder, Malm and Beskow34 these were often not adjusted for in the analysis. Reference Smoot and Gonzales18,Reference Whittington and Wykes27,Reference Wondrak and Dolan29–Reference Sjostrom, Eder, Malm and Beskow34 Where wards or units were the units of allocation and/or analyses, insufficient information was provided about the baseline equivalence of these. Reference Lee, Gray and Gournay35,Reference Nijman, Merckelbach, Allertz and A Campo36 A number of uncontrolled studies failed to report on possible population/organisational differences between pre-and-post-intervention periods. Reference McLaughlin, Bonner, Mboche and Fairlie22–Reference Goodykoontz and Herrick24,Reference Jonikas, Cook, Rosen, Laris and Kim37–Reference Bjorkdahl, Hansebo and Palmstierna40 The eight studies reporting participant withdrawals (Table 2) had a mean retention rate of 72.7% (s.d. = 19.66, range 32–91.1%).

Table 2 Quality appraisal outcomes

| Study reference | Selection bias |

Study design |

Confounders | Blinding | Data

collection methods |

Withdrawals and dropouts |

Global rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carmel Reference Carmel and Hunter41 | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Smoot & Gonzales Reference Smoot and Gonzales18 | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Nau et al Reference Nau, Halfens, Needham and Dassen9 | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate |

| Nau et al Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens28 | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate |

| Lee et al Reference Lee, Gray and Gournay35 | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Infantino & Musingo Reference Infantino and Musingo30 | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Needham et al Reference Needham, Abderhalden, Meer, Dassen, Haug and Halfens26 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Rice et al Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31 | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate |

| Ilkiw-Lavelle et al Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20 | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Moderate |

| Paterson et al Reference Paterson, Turnbull and Aitken46 | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate |

| Calabro et al Reference Calabro, Mackey and Williams45 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Moderate | Moderate |

| Thackrey Reference Thackrey33 | Strong | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Needham et al Reference Needham, Abderhalden, Zeller, Dassen, Haug and Fischer49 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Nau et al Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens21 | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Moderate |

| Hahn et al Reference Hahn, Needham and Abderhalden13 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Bowers et al Reference Bowers, Brennan, Flood, Lipang and Oladapo52 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Bowers et al Reference Bowers, Flood, Brennan and Allan51 | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Laker et al Reference Laker, Gray and Flach25 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Weak | Moderate |

| Whittington & Wykes Reference Whittington and Wykes27 | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| Nijman et al Reference Nijman, Merckelbach, Allertz and A Campo36 | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| Jonikas et al Reference Jonikas, Cook, Rosen, Laris and Kim37 | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| Cowin et al Reference Cowin, Davies, Estall, Berlin, Fitzgerald and Hoot47 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Wondrak & Dolan Reference Wondrak and Dolan29 | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Beech & Leather Reference Beech and Leather43 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Beech Reference Beech42 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Beech Reference Beech19 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Martin Reference Martin39 | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Grenyer et al Reference Grenyer, Ilkiw-Lavalle, Biro, Middleby-Clements, Comninos and Coleman50 | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| Sjostrom et al Reference Sjostrom, Eder, Malm and Beskow34 | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| McLaughlin et al Reference McLaughlin, Bonner, Mboche and Fairlie22 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Moore Reference Moore38 | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Goodykoontz & Herrick Reference Goodykoontz and Herrick24 | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak |

| Taylor & Sambrook Reference Taylor and Sambrook53 | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Gertz Reference Gertz23 | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| Robinson et al Reference Robinson, Hills and Kelly48 | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak |

| McIntosh Reference McIntosh32 | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| Collins Reference Collins44 | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Moderate | Weak |

| Bjorkdahl et al Reference Bjorkdahl, Hansebo and Palmstierna40 | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Weak |

Included studies examining intervention effectiveness were limited by the absence of active controls in all but two studies. Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31,Reference Carmel and Hunter41 Four studies where de-escalation performance was rated by independent assessors reported good blinding procedures. Reference Nau, Halfens, Needham and Dassen9,Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens28,Reference Wondrak and Dolan29,Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31 Studies frequently failed to evidence adequate validity and reliability of outcome measures (Table 2). Of nine studies providing evidence of potential moderators of effectiveness, Reference Nau, Halfens, Needham and Dassen9,Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20,Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens28,Reference Wondrak and Dolan29,Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31,Reference McIntosh32,Reference Beech42–Reference Collins44 only three Reference Nau, Halfens, Needham and Dassen9,Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20,Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens28 met at least three of the four key quality criteria for moderator analyses. Of the seven studies providing a qualitative evaluation of the acceptability of training, Reference Smoot and Gonzales18–Reference Goodykoontz and Herrick24 none provided sufficient methodological detail to meet any of the COREQ quality standards.

Direct skills-teaching as a predictor of improved de-escalation performance and related outcomes

Cognitive outcomes

Included studies generally supported the capacity of training to enhance de-escalation-related knowledge. Of five studies providing pre/post-training data on this outcome, the four of comparable study quality (moderate) and training intensity (medium) Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20,Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31,Reference Calabro, Mackey and Williams45,Reference Paterson, Turnbull and Aitken46

were consistent in finding large (ES = 0.91, Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31 ES = 1.13, Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20 ES = 1.39 Reference Calabro, Mackey and Williams45 ) and significant de-escalation-related knowledge gains associated with training. Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20,Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31,Reference Calabro, Mackey and Williams45,Reference Paterson, Turnbull and Aitken46 The final study, using a low-intensity intervention, found no effect (ES = –0.14) on knowledge. Reference Cowin, Davies, Estall, Berlin, Fitzgerald and Hoot47

Moderators of cognitive outcomes. There was no evidence of differences in knowledge gains between professional groups pre- and post-training, Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20 but a regression analysis found staff occupation, rather than current level of clinical exposure to aggression predicted baseline level of de-escalation knowledge. Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20 This suggests that experience and prior training rather than exposure to aggression predicts de-escalation knowledge. Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20 As might be expected, staff with no prior training improved the most. Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20

Affective outcomes

Findings were consistent across study design, quality and training intensity in supporting increased confidence to manage aggression associated with training. Nine of 10 studies reported significantly increased confidence post-training. Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens21,Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens28,Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31–Reference Thackrey33,Reference Calabro, Mackey and Williams45,Reference Robinson, Hills and Kelly48–Reference Grenyer, Ilkiw-Lavalle, Biro, Middleby-Clements, Comninos and Coleman50 However, effect sizes were only calculable for four studies, with two negligible effects (ES<0.2), Reference McIntosh32,Reference Calabro, Mackey and Williams45 one medium-sized effect (ES = 0.76) Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31 and one large (ES = 1.04) Reference Grenyer, Ilkiw-Lavalle, Biro, Middleby-Clements, Comninos and Coleman50 . Increases in confidence after training were reported elsewhere but the significance of this finding was not evaluated. Reference McLaughlin, Bonner, Mboche and Fairlie22 Surprisingly, given the evidence of increased confidence, there was no evidence that the training impacted on subjective anxiety regulation in the management of aggression, Reference Beech19,Reference Wondrak and Dolan29,Reference McIntosh32,Reference Beech and Leather43 although one study reported a medium-sized (ES = 0.54) non-significant reduction in feelings of anxiety post-training. Reference Wondrak and Dolan29 There was some, albeit limited, evidence that training may, in the short term, sensitise participants to the risk of assault and increase anxiety. Reference McIntosh32

Moderators of affective outcomes. Three studies revealed potential moderators of affective outcomes. As expected, more experienced staff had the highest levels of confidence to manage aggression. Reference McIntosh32 Staff working in areas of greatest acuity appear to benefit most in terms of confidence gains from training, Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31 and male participants may rate themselves as more able to regulate anxiety when faced with aggression than female participants. Reference Beech42

Skills-based outcomes

The six studies investigating skill improvements varied in both study quality and training intensity but generally supported the capacity of training to improve de-escalation performance. Four studies reported significant objectively measured post-training improvements Reference Nau, Halfens, Needham and Dassen9,Reference Wondrak and Dolan29,Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31,Reference Paterson, Turnbull and Aitken46 (effect sizes calculable for only two studies both demonstrating large effect sizes >0.8); Reference Wondrak and Dolan29,Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31 and there also was evidence of self-rated improvements. Reference Beech19 Negative findings included reduction in self-rated de-escalation ability after training Reference Beech and Leather43 and objectively measured improvements not reflected in participants’ subjective ratings. Reference Wondrak and Dolan29

Moderators of skills-based outcomes. There was evidence that neither confidence Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens28 nor anxiety regulation Reference Wondrak and Dolan29,Reference McIntosh32 may be reliable predictors of de-escalation performance and that the ability to interpersonally relate to aggressive patients has the more pivotal role. Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens28,Reference McIntosh32 No relationship between age, experience or previous education and de-escalation performance was identified. Reference Nau, Halfens, Needham and Dassen9 The largest gains in de-escalation performance were found in trainees with the lowest baseline performance. Reference Nau, Halfens, Needham and Dassen9 Males and trainees with previous violence and aggression training attendance had higher self-rated de-escalation ability. Reference Beech42

Clinical outcomes

Assault rate. Irrespective of study design, quality or training intensity, findings for this outcome were mixed. No clear evidence of the impact of this training on assault rate could therefore be derived. Of five studies measuring risk of assault at ward level, three found a significantly reduced risk of assault Reference Needham, Abderhalden, Meer, Dassen, Haug and Halfens26,Reference Whittington and Wykes27,Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31 and two found no significant effect. Reference Sjostrom, Eder, Malm and Beskow34,Reference Nijman, Merckelbach, Allertz and A Campo36 Three studies measured the risk of assault at the level of individual staff and only one Reference Infantino and Musingo30 found a significant reduction (ES = 0.77), with two reporting no effect of training. Reference Needham, Abderhalden, Meer, Dassen, Haug and Halfens26,Reference Whittington and Wykes27

Incidence of aggression. Eleven studies investigated the impact of training on aggressive incidents more broadly, which included verbal aggression and violence towards objects. Findings were often negative, irrespective of training intensity or study quality, with studies either reporting no effect on incident rate or severity, Reference Laker, Gray and Flach25,Reference Sjostrom, Eder, Malm and Beskow34,Reference Nijman, Merckelbach, Allertz and A Campo36,Reference Carmel and Hunter41 or increases in aggression post-training (probably because of improved reporting post-training). Reference Martin39 There was even evidence that de-escalation trained wards increased staff risk of exposure to being involved in an aggressive incident when compared with control and restraint trained wards, Reference Lee, Gray and Gournay35 but there was a high risk of other programmatic or organisational variables being responsible for this outcome. Again, there was evidence of a significant reduction in incident rates measured at ward level Reference Needham, Abderhalden, Meer, Dassen, Haug and Halfens26,Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31 in two studies of moderate quality, one of these demonstrating a medium effect size (ES = 0.64). Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31 Significant reductions in severity of incidents were also reported, Reference Needham, Abderhalden, Meer, Dassen, Haug and Halfens26,Reference Nijman, Merckelbach, Allertz and A Campo36 although the significance of this effect was marginal (P = 0.52) in one of these. Reference Nijman, Merckelbach, Allertz and A Campo36 Three weak studies reported reductions in incident rate but failed to evaluate the significance of these effects. Reference McLaughlin, Bonner, Mboche and Fairlie22–Reference Goodykoontz and Herrick24

Injuries. Results were again mixed, although the stronger two of four studies evaluating this outcome demonstrated positive effects in reducing injuries. Reference Infantino and Musingo30,Reference Carmel and Hunter41 There was evidence of a significant and large (ES = 1.13) reduction in wards with high compliance with training compared with low compliance wards and the active control (cardiopulmonary resuscitation training). Reference Carmel and Hunter41 This reduction was not found at individual staff level where the training was marginally outperformed by the active control in terms of reduced risk of injury (training: ES = 0.3, CPR: ES = 0.37); although a significant reduction at individual staff level was found in another study of similar design and quality. Reference Infantino and Musingo30 Two weak studies found no effect on injury rates. Reference Moore38,Reference Martin39

Containment. The four studies investigating impact of training on use of physical restraint all demonstrated reductions associated with training. Reference Laker, Gray and Flach25,Reference Needham, Abderhalden, Meer, Dassen, Haug and Halfens26,Reference Jonikas, Cook, Rosen, Laris and Kim37,Reference Moore38 However, interpretation of these findings was limited by poor study quality Reference Jonikas, Cook, Rosen, Laris and Kim37,Reference Moore38 and, in one instance, a wide confidence interval (CI = 0.168–0.940). Reference Laker, Gray and Flach25 A non-significant reduction in the use of rapid tranquillisation Reference Laker, Gray and Flach25 and no effect on the supply of extra medication Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31 were also reported.

Moderators of clinical outcomes. No moderators of clinical outcomes were identified.

Organisational outcomes

A range of organisational benefits was reported among six studies that provided data on this outcome. These included a highly significant, large (ES = 1.47) reduction in lost workdays Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31 and two weak studies also supported this finding but failed to evaluate significance. Reference Smoot and Gonzales18,Reference Martin39 Further benefits, reported without evaluating significance, included improved staff retention, Reference Smoot and Gonzales18 reduced complaints Reference Smoot and Gonzales18 and reduced overall expenditure. Reference Smoot and Gonzales18,Reference Martin39 There were negative findings, including a non-significant increase in sick leave Reference Sjostrom, Eder, Malm and Beskow34 and increased patient hospitalisation periods for de-escalation trained wards compared with control and restraint trained wards. Reference Lee, Gray and Gournay35 However, variation in programmatic or organisational variations between study sites limits the interpretation of these data. No moderators of organisational outcomes were identified.

Attitudinal change as a predictor of improved de-escalation related outcomes

No study of moderate quality or above provided any evidence of attitudinal change impacting de-escalation performance or rates of violence and aggression. Reference Hahn, Needham and Abderhalden13,Reference Needham, Abderhalden, Zeller, Dassen, Haug and Fischer49,Reference Bowers, Flood, Brennan and Allan51,Reference Bowers, Brennan, Flood, Lipang and Oladapo52 Of three studies that used adequately validated scales, one measured attitudes toward patients in general Reference Bowers, Brennan, Flood, Lipang and Oladapo52 and two measured attitudes toward aggression. Reference Hahn, Needham and Abderhalden13,Reference Needham, Abderhalden, Zeller, Dassen, Haug and Fischer49 Improvements in de-escalation performance were assumed via measured increases in confidence to manage patient aggression, Reference Needham, Abderhalden, Zeller, Dassen, Haug and Fischer49 via preference for aggression management method (an increase in preferences for non-physical methods indicating a positive result) Reference Hahn, Needham and Abderhalden13 or via reductions in staff-patient conflict. Reference Bowers, Brennan, Flood, Lipang and Oladapo52

None of these studies influenced staff attitudes in the hypothesised direction. Reference Hahn, Needham and Abderhalden13,Reference Needham, Abderhalden, Zeller, Dassen, Haug and Fischer49,Reference Bowers, Brennan, Flood, Lipang and Oladapo52 Noting this, there were anomalous findings: desirable outcomes (increased confidence to manage aggression Reference Needham, Abderhalden, Zeller, Dassen, Haug and Fischer49 ) and reduced staff-patient conflict Reference Bowers, Brennan, Flood, Lipang and Oladapo52 (although with a negligible effect size, ES = 0.13) were achieved independently of attitudinal change. It should be noted that when this study was repeated using a more rigorous, controlled design, no effect on conflict was observed. Reference Bowers, Flood, Brennan and Allan51 Evidence to support attitudinal change to patient aggression as a mechanism for improving de-escalation related outcomes was only found in weak studies. Reference Beech19,Reference McLaughlin, Bonner, Mboche and Fairlie22,Reference Bjorkdahl, Hansebo and Palmstierna40,Reference Collins44,Reference Grenyer, Ilkiw-Lavalle, Biro, Middleby-Clements, Comninos and Coleman50,Reference Taylor and Sambrook53

Moderators of attitudinal change

Potential moderators of attitudinal change were evident from three studies. Reference Beech42–Reference Collins44 Staff may attribute more blame for aggression to younger patients than older patients, Reference Beech42,Reference Beech and Leather43 but attitudes to aggression in younger patients may be more amenable to change through training. Reference Beech42,Reference Beech and Leather43 Older staff attributed less blame to aggressive patients than did younger participants Reference Beech42 and nurses with more clinical experience may be more likely to have positive attitudes towards patient aggression. Reference Collins44 Blame attributions were found to have increased at clinical placement follow-up from post-training scores in two studies, suggesting either a negative interaction between attitudes to aggression and exposure to clinical placement or a reduction in effect over time. Reference Beech42,Reference Collins44 No conclusions could be made about the relationship between exposure to previous aggressive incidents and blame attribution. Reference Beech42

Acceptability of training interventions

Seven studies provided some rudimentary qualitative evaluation of training interventions but were weak in methodological quality. All studies, except one, in which a large number of participants perceived no impact of the training on their practice, Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens21 reported positive views of the training. The reasons for the negative finding were not established. Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens21 Improvements participants felt were important for the training included the following four themes:

Duration and frequency of training

The participants expressed the importance of increasing the frequency of training and regular refresher courses to maintain learning. Reference Smoot and Gonzales18,Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20,Reference McLaughlin, Bonner, Mboche and Fairlie22,Reference Goodykoontz and Herrick24

Delivery methods

Participants felt that the training should be relevant to the clinical context in which they work Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20 and that trainer supervision and feedback on actual clinical interactions would be useful. Reference Smoot and Gonzales18,Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20 They wanted a stronger emphasis on role plays and a broad spectrum of case studies Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20,Reference Goodykoontz and Herrick24 and there was a preference for live demonstrations rather than videotaped scenarios. Reference Goodykoontz and Herrick24 They also wanted a written manual on de-escalation to keep with them on the wards. Reference Smoot and Gonzales18 The importance of delivering training to all levels of the multidisciplinary team and training whole wards together to enable team approaches was emphasised. Reference McLaughlin, Bonner, Mboche and Fairlie22,Reference Gertz23

Intervention content

There was evidence of a perceived need for training content that considered aggression from a range of perspectives, i.e. aggression motivated by both illness and non-illness factors. Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20

Facilitator attributes

Participants wanted trainers to have practice credibility (i.e. current ward experience) so that training content could be directly linked to situations participants experience on the wards. Reference Ilkiw-Lavalle, Grenyer and Graham20

Discussion

This review has synthesised the available evidence pertaining to de-escalation techniques training. There was insufficient evidence to consistently demonstrate cognitive, affective, skills-based improvements and transfer to enhanced job performance either through direct skills-teaching or attitude modification. De-escalation techniques are interventions predicated on a desire to enhance safety through reducing violence and the physical and psychological harms associated with it. It is thus somewhat surprising that only 18 of the 38 included studies measured effectiveness via key safety outcomes such as rates of violence and aggression and/or the use of potentially harmful Reference Paterson, Bradley, Stark, Saddler, Leadbetter and Allen3 containment strategies such as physical restraint. Furthermore, a large proportion of the included studies were rated as methodologically weak. Therefore, given the limited quality of the existing evidence, only tentative conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of this intervention.

Direct skills-teaching

The strongest impact of training was on de-escalation knowledge and participant confidence to manage aggressive behaviour. There was evidence that confidence alone may not be particularly useful in terms of predicting improvements in actual behaviour when faced with aggression. There may be no relationship between confidence to manage aggression and de-escalation performance, Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens28 possibly because excessive self-confidence may be perceived as threatening to the aggressor and counterproductive to de-escalation efforts. Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens28 It is possible that qualities such as self-awareness and the ability to connect interpersonally with patients may have a more pivotal role in effective de-escalation. Reference Nau, Dassen, Needham and Halfens28,Reference McIntosh32 Measurement of these outcomes, rather than confidence, may be more appropriate in future intervention research.

This review found consistent evidence of objectively measured improvements in de-escalation performance post-training. However, these improvements were often measured on un-validated scales and limited to artificial training scenarios. As such, little can be concluded about the effective transfer of these skills to aggressive situations during routine practice. This review identified no evidence that age, occupation, level of experience or gender are reliable predictors of de-escalation performance, either at baseline, endpoint or in terms of extent of improvement as a result of training. Within the limited evidence available, there is therefore nothing to suggest that clinical managers should prioritise certain subgroups of staff over others for de-escalation training.

Few strong conclusions can be drawn about the impact of training on assaults, injuries, containment and organisational outcomes owing to (1) the poor quality of evidence and (2) conflicting results. The most consistent evidence of impact on clinical outcomes was on rates of violence, aggression and injuries at ward rather than individual level. Wards with high compliance with training appear to benefit more from training than those with low compliance. Reference Whittington and Wykes27,Reference Rice, Helzel, Varney and Quinsey31,Reference Carmel and Hunter41 This may be explained through wards adopting whole-team approaches that are more likely to reduce the risk of assault than individual advances in knowledge and skills. Reference Carmel and Hunter41 Clinical managers should not only ensure that sufficient numbers of their staff are trained, but also that as many staff as possible are trained together at the same time, to foster such approaches and facilitate maximal gain.

Attitude modification

There was little evidence to suggest that de-escalation skills may be influenced through modification of staff attitudes. No study using validated measures detected positive attitudinal changes to patients or to aggression. Although one study reported significant reductions in conflict, Reference Bowers, Brennan, Flood, Lipang and Oladapo52 the effect size was small and the effect was not found when the study was repeated under more rigorous conditions. Reference Bowers, Flood, Brennan and Allan51 Although there was evidence of increased confidence to manage aggression following an intervention aiming to modify attitudes to patient aggression, Reference Needham, Abderhalden, Zeller, Dassen, Haug and Fischer49 given the lack of evidence of attitudinal change, it is possible that another mechanism was responsible for this positive result.

The negative findings are consistent with the broader literature, which is replete with failed attempts to modify mental health staff attitudes to patient aggression. Reference Endley and Berry14,Reference Needham, Abderhalden and Halfens54 This may be explained either through the inability of interventions to impact on attitudes or the inability of the available measures to detect existing attitudinal changes. Reference Needham, Abderhalden and Halfens54 The negative results may further reflect a more pervasive problem with stigmatising attitudes of mental health staff towards patients. While there is evidence of reductions in negative attitudes towards the mentally ill among the UK public as a result of the recent ‘Time to Change’ public health campaign, Reference Taylor and Sambrook53 the effects of the same campaign had no impact on the attitudes of mental health professionals. Reference Corker, Hamilton, Henderson, Weeks, Pinfold and Rose55 More responsive interventions to change these attitudes and potentially more sensitive tools for detecting attitudinal change are needed to support this training mechanism as a means of improving staff de-escalation techniques.

Review limitations

To limit heterogeneity of training interventions included, only studies of healthcare staff working with working age adult (18–65) populations were reviewed. It is probable that, to meet the specific needs of populations outside this group, substantial variation in training exists. This decision was therefore intended to enhance the precision of the review’s findings and conclusions. However, it is accepted that this may have excluded potentially relevant data. It is also possible that the exclusion of grey literature may have excluded potentially relevant data. The inclusion criteria for included interventions were relatively broad and, as such, these included additional components delivered in conjunction with de-escalation content (such as physical restraint training). This was a pragmatic decision based on the observation that this is (1) often how the intervention is delivered in practice, Reference Bowers, Nijman, Allan, Simpson, Warren and Turner56 and (2) these interventions make up a substantial proportion of the evaluation research on this topic. Nevertheless, this may have complicated the isolation of the effect of the de-escalation components of the interventions. However, assessments of the effectiveness of de-escalation components could often be deduced from the nature of the outcome. For example, reductions in aggressive incidents and restraint usage would likely be a consequence of enhanced de-escalation techniques rather than learnt restraint techniques. Extractions and quality appraisal decisions were verified rather than independently conducted, which may have increased the risk of error/bias at these stages. Finally, due to the nature of existing evidence, the sample of studies was biased towards unqualified and student nurse populations. These factors may have reduced the generalisability of the review findings.

Recommendations

The development of evidence-based interventions followed by feasibility studies measuring both de-escalation performance and transfer to enhanced clinical and organisational outcomes is needed. This may require either new measures of de-escalation performance or further validation of existing measures. The limited acceptability data suggest that trainees are supportive of increased use of role play, case studies and prefer facilitators with relevant practice credibility. However, no empirical evidence of the relative effectiveness of methods of delivery or facilitator attributes was identified. Future work should include qualitative inquiry exploring issues of transfer of training to improved performance and the optimum delivery methods for this form of training. As a minimum, this should be conducted with staff who receive the training and training facilitators. Training staff in non-physical conflict resolution represents a substantial and costly proportion of NHS mandatory training. It is assumed that this training may improve staff’s ability to de-escalate violent and aggressive behaviour. There is currently limited evidence to suggest that this form of training has this desirable effect.

Funding

O.P. has received a Doctoral Research Fellowship from the National Institute of Health Research to explore ways of improving mental health staff use of de-escalation techniques. This review represents one part of the fellowship project.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.