Depressive and anxiety disorders are commonly occurring conditions, with lifetime-to-date prevalence estimates of up to 17% reported for major depressive disorder and 4–7% for generalised anxiety disorder, based upon large-scale surveys of adult mental disorders in the general population (Reference Horwath, Cohen, Weissman, Tsuang and TohenHorwath et al, 2002). These conditions impose an enormous economic and social burden on the provision of public health services, evidenced for example by over 24 million prescriptions being written for antidepressants in England during 2001 (Department of Health, 2002). Work has focused on quantifying the effects of depressive and anxiety disorders on physical and psychosocial functioning (Reference Wells, Stewart and HaysWells et al, 1989; Reference Ormel, Vonkorff and UstunOrmel et al, 1994), both cross-sectionally and prospectively. Although evidence for the profound impact of depressive conditions on public health is compelling, there is still sparse evidence concerning the specific impact of anxiety states. Knowledge concerning the impact of depressive and anxiety states on the perception by individuals of their own health status in the context of chronic medical illness has been gained almost exclusively from the study of patient groups. We now report findings from a population-based study.

METHOD

During 1993–1997, 30 414 men and women then aged 40–74 years and resident in Norfolk, UK, were recruited for the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC–Norfolk) population study using general practice age–gender registers. They completed a baseline questionnaire that included the question ‘Have you ever been told by a doctor that you have any of the following conditions?’ followed by a list of medical conditions. These included diagnoses concerned with circulation, vision, digestive system, chest (including allergies), bone and tumours. Where any condition was reported, participants were asked also to report their age when first diagnosed.

During 1996–2000 an assessment of social and psychological circumstances, based upon the Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire (HLEQ; Reference Surtees, Wainwright and BrayneSurtees et al, 2000), was completed by a total of 20 921 participants, representing a response rate of 73.2% from the total eligible EPIC–Norfolk sample (28 582). The HLEQ instrument included a structured self-assessment approach to psychiatric symptoms representative of selected DSM–IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for major depressive disorder and generalised anxiety disorder and designed to identify those EPIC–HLEQ participants thought likely to have met putative diagnoses at any time in their lives. Where any episode was reported, respondents were asked also to estimate onset and (if appropriate) offset timings, and to provide an outline of previous history that included age at first onset and subsequent episode recurrence. The approach was designed to provide feasible measures of emotional state, using currently applied diagnostic criteria for inclusion in a large-scale chronic disease epidemiology project (Reference Surtees, Wainwright and BrayneSurtees et al, 2000; Reference Wainwright and SurteesWainwright & Surtees, 2002).

The HLEQ also included the anglicised Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF–36), a validated generic measure of subjective health status (Reference Ware and SherbourneWare & Sherbourne, 1992; Reference Ware, Snow and KosinskiWare et al, 1993) that includes eight multi-item independent health dimensions: physical functioning, social functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, role limitations due to emotional problems, mental health, energy/vitality, pain and general health perception. Subsequent advances in the scoring of the SF–36 have provided for two higher-order summary scores, representing overall physical and mental health functioning, based on a factor analysis that captured over 80% of the variance in the eight subscales (Ware et al, Reference Ware, Snow and Kosinski1993, Reference Ware, Kosinski and Keller1994). The two higher-order summary scores – the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS) – were derived according to algorithms specified by the original developers (Ware et al, Reference Ware, Snow and Kosinski1993, Reference Ware, Kosinski and Keller1994). The sub-scales were scored on a health scale from 0 (worst) to 100 (best). Missing values were imputed where at least half of the items were available for each individual scale (Reference Ware, Snow and KosinskiWare et al, 1993). The PCS and MCS scores were created by aggregating across the eight SF–36 subscales, transformed to z scores and multiplied by their respective factor score coefficients, and standardised as T scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. Factor score coefficients used to derive the component scores were based upon a US (Reference Ware, Kosinski and KellerWare et al, 1994) as opposed to a UK population on the basis of uniformity for cross-national comparisons (Reference JenkinsonJenkinson, 1999).

Statistical analysis

We identified those with any of four chronic medical conditions: cancer (not including skin cancers, and confirmed by data from the East Anglia cancer registry), diabetes, myocardial infarction or stroke. Prevalent major depressive disorder and generalised anxiety disorder were defined as any episodes that were ongoing or were reported to have offset within the 12 months prior to HLEQ completion. Mean SF–36 sub-scale and summary component scores (PCS and MCS) are presented by gender (adjusted for age) and for men and women combined (adjusted for age, gender and age–gender interaction). These were derived from linear regression models, with age included as a categorical variable in 5-year bands. Effect size is calculated as the reduction in mean component scores, expressed in terms of US population standard deviations (the US population standard deviation is 10; Reference Ware, Kosinski and KellerWare et al, 1994).

RESULTS

The mean age of the EPIC–HLEQ participants was 61 years (s.d.=9.3, range=41–80 years). Table 1 shows the prevalence of each of the four chronic medical conditions and of both mood disorders assessed in the EPIC–HLEQ cohort (n=20 921). Overall, 9.3% of participants (n=1953) reported at least one of the four chronic medical conditions, with cancer being the most commonly reported condition (3.6%) and 139 participants (0.7%) reporting more than one medical condition. Men had higher prevalence rates of diabetes, myocardial infarction and stroke and lower cancer rates than women. Overall, 6.3% of participants (n=1328) reported either (12-month) prevalent major depressive disorder or generalised anxiety disorder (with the former reported over twice as frequently as the latter) and 1.1% (n=231) reported both major depressive disorder and generalised anxiety disorder. Prevalence of both major depressive disorder and generalised anxiety disorder was about 1.5 times as great in women as in men.

Table 1 Prevalence (% (n)) of chronic medical conditions and mood disorders in the Norfolk cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC–Norfolk, n=20 921) who completed the Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire

| Men | Women | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic medical conditions | |||

| Diabetes | 3.1 (280) | 1.6 (189) | 2.2 (469) |

| Cancer | 2.1 (194) | 4.8 (563) | 3.6 (757) |

| Myocardial infarction | 5.0 (459) | 1.3 (158) | 2.9 (617) |

| Stroke | 1.6 (145) | 1.0 (115) | 1.2 (260) |

| Any | 10.7 (976) | 8.3 (977) | 9.3 (1953) |

| Multiple | 1.0 (93) | 0.4 (46) | 0.7 (139) |

| Prevalent mood disorders | |||

| Major depressive disorder | 3.8 (343) | 6.4 (754) | 5.2 (1097) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 1.7 (158) | 2.6 (304) | 2.2 (462) |

| Either | 4.5 (414) | 7.7 (914) | 6.3 (1328) |

| Both | 1.0 (87) | 1.2 (144) | 1.1 (231) |

| Chronic medical conditions and/or prevalent mood disorders | |||

| Neither | 85.2 (7753) | 84.7 (10 014) | 84.9 (17 767) |

| Medical only | 10.3 (934) | 7.5 (892) | 8.7 (1826) |

| Mood only | 4.1 (372) | 7.0 (829) | 5.7 (1201) |

| Both | 0.5 (42) | 0.7 (85) | 0.6 (127) |

Of the HLEQ sample, PCS and MCS scores were available for 19 535 participants (93.4%). Non-responders had higher rates of (any) chronic medical conditions than responders (12.4% v. 9.1%) but no differences were observed in the prevalence of (either) mood disorder (6.0% v. 6.4%). Mean (s.d.) scores were 47.4 (10.2) for the PCS and 52.2 (9.4) for the MCS. In line with the results of other studies, PCS scores declined rapidly with increasing age, whereas MCS scores increased with age. Mean PCS scores were 51.3, 49.4, 46.7 and 42.8 for those aged 41–49, 50–59, 60–69 and 70–80 years, respectively. This corresponds to a 3.2-point decrease (95% CI 3.0–3.3) in the mean PCS score for every 10-year increase in age (from linear regression, with age included as a continuous variable). This decrease in PCS score was the same for men as for women. Overall, men reported higher scores than women on both the PCS (47.7 v. 47.1) and the MCS (52.9 v. 51.6).

Table 2 shows age–gender-adjusted mean SF–36 component summary scores according to the presence or absence of chronic medical conditions and prevalent mood disorders. Significant reductions in both PCS and MCS scores were associated with chronic medical conditions and with prevalent mood disorders. Participants reporting any chronic medical condition had mean PCS scores reduced by 4.7 points and mean MCS scores reduced by 1.9 points. Of the individual medical conditions, stroke was associated with the greatest impact on PCS, with diabetes, myocardial infarction and stroke all having a similar effect on the MCS. Cancer was associated with the smallest reductions in both the PCS and the MCS. The presence of more than one medical condition was associated with a further reduction in both the PCS and MCS scores. Effect sizes tended to be slightly greater for men than for women on the PCS (but not the MCS), although the pattern of results remained the same.

Table 2 Age–gender-adjusted mean Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF–36) component summary scores and effect sizes according to the presence/absence of chronic medical conditions and prevalent mood disorders

| PCS | MCS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | All | Effect size1 | Men | Women | All | Effect size1 | |

| Chronic medical conditions | ||||||||

| Diabetes | 43.0*** | 44.0*** | 43.4*** | 0.5 | 52.4* | 50.5** | 51.5*** | 0.3 |

| Cancer | 43.8*** | 45.0*** | 44.7*** | 0.4 | 52.5 | 52.8 | 53.0 | 0.1 |

| MI | 42.1*** | 42.0*** | 42.0*** | 0.6 | 52.1*** | 51.0 | 51.5*** | 0.3 |

| Stroke | 41.1*** | 42.5*** | 41.7*** | 0.7 | 51.3** | 50.3* | 50.8*** | 0.3 |

| Any | 43.0*** | 44.3*** | 43.6*** | 0.5 | 52.3*** | 51.9* | 52.1*** | 0.2 |

| Multiple | 37.9*** | 39.8*** | 38.5*** | 1.0 | 50.6** | 50.8 | 50.5** | 0.4 |

| Prevalent mood disorders | ||||||||

| MDD | 43.4*** | 44.8*** | 44.4*** | 0.4 | 38.3*** | 40.6*** | 40.0*** | 1.4 |

| GAD | 41.1*** | 42.4*** | 42.0*** | 0.6 | 36.5*** | 39.1*** | 38.3*** | 1.6 |

| Either | 42.8*** | 44.7*** | 44.0*** | 0.4 | 38.4*** | 40.7*** | 40.1*** | 1.4 |

| Both | 41.9*** | 41.1*** | 41.4*** | 0.7 | 33.9*** | 36.7*** | 35.8*** | 1.8 |

| Chronic medical conditions and/or prevalent mood disorders | ||||||||

| Neither | 48.4 | 48.2 | 48.3 | — | 54.3 | 53.6 | 54.0 | — |

| Medical only | 43.3 | 44.9 | 44.1 | 0.4 | 52.9 | 52.9 | 52.9 | 0.1 |

| Mood only | 43.6 | 45.4 | 44.8 | 0.4 | 38.6 | 40.6 | 40.1 | 1.4 |

| Both | 36.1*** | 38.4*** | 37.6*** | 1.1 | 37.0*** | 42.2*** | 40.6*** | 1.3 |

Participants reporting either mood disorder had mean PCS scores reduced by 4.3 points and mean MCS scores reduced by 14.0 points. Meeting putative diagnostic criteria for generalised anxiety disorder was associated with slightly greater reductions in mean PCS and MCS scores than with major depressive disorder. Again, the report of prevalent psychiatric symptoms sufficient to meet putative diagnostic criteria for both major depressive disorder and generalised anxiety disorder was associated with a further reduction in both the PCS and MCS mean scores. In addition, effect sizes were greater for men than for women on both the PCS and the MCS.

Importantly, the reduction in PCS mean score associated with any mood disorder was of equivalent magnitude to that for any medical condition. However, for MCS the mean score reduction associated with either mood disorder was far greater than for any medical disorder. The presence of comorbid medical and mood disorders was associated with a further reduction in the PCS but not the MCS score.

After additional adjustment for mood disorders, the reduction in mean PCS scores associated with the presence of at least one of the four medical conditions was 4.4 points (95% CI 3.9–4.9). After adjustment for medical conditions, the reduction in mean PCS scores associated with prevalent major depressive disorder or generalised anxiety disorder was 3.7 points (3.2–4.3). The impact of mood disorders on physical functioning remained of equivalent magnitude to the impact of chronic medical conditions. This mean reduction in physical functioning was equivalent to the mean reduction associated with being 12 years older.

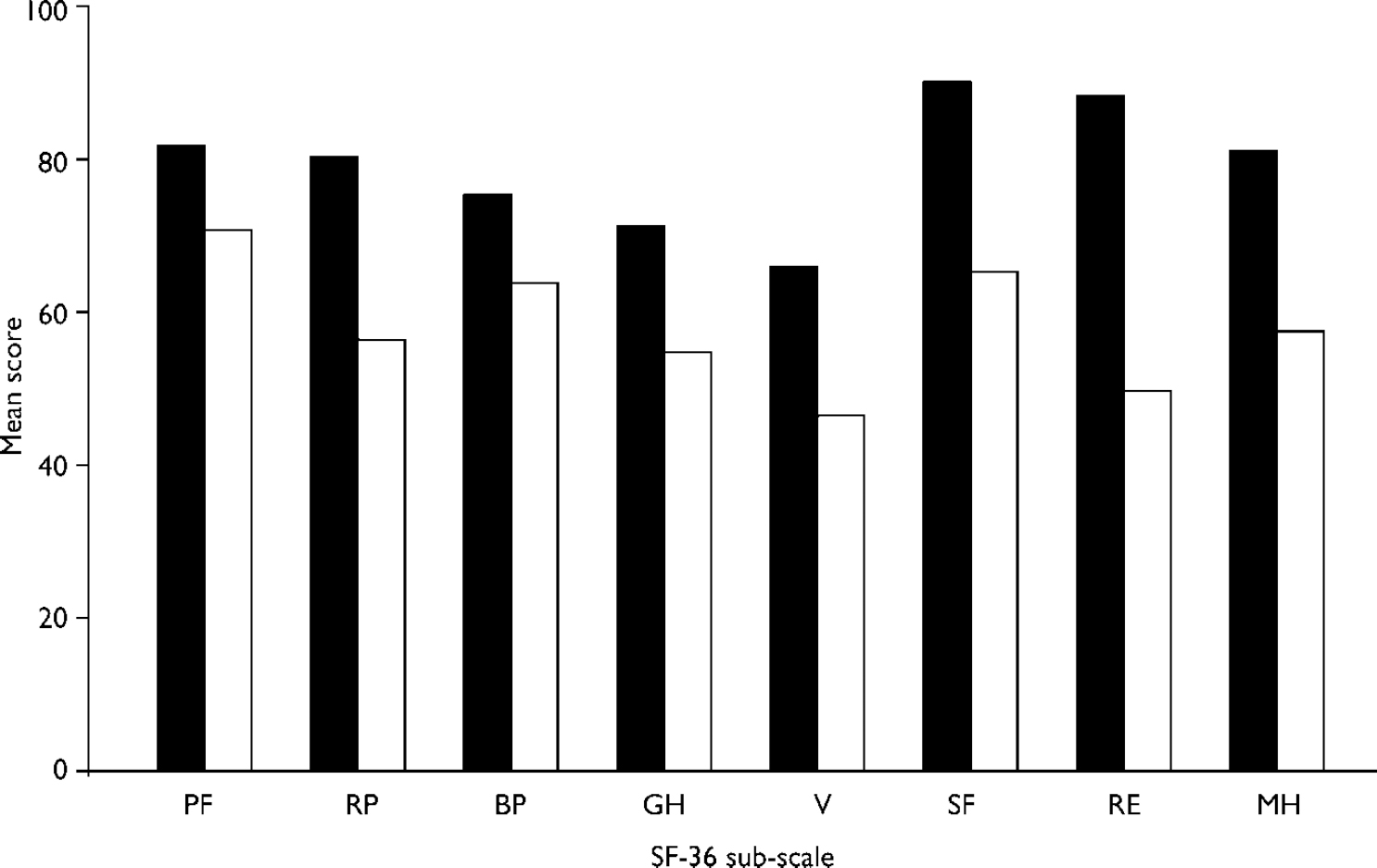

Figure 1 shows profiles of the eight individual sub-scales in the presence/absence of mood disorders, adjusted for age, gender and medical conditions. The figure shows that after taking medical conditions into account the reduction in mean scores is greatest for the Social Functioning, Role Emotional and Mental Health sub-scales, but that mood disorders have an impact across the whole range of SF–36 sub-scales.

Fig. 1 Profiles of mean Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF–36) sub-scale scores according to the absence (▪) or presence (□) of prevalent mood disorders (adjusted for age, gender and presence of any chronic medical conditions), sub-scales are: PF=Physical Functioning; RP, Role Physical; BP, Bodily Pain; GH, General Health; V, Vitality; SF, Social Functioning; RE, Role Emotional; MH, Mental Health.

DISCUSSION

Key findings

This study provides evidence that the degree of subjective physical functional impairment associated with mood disorders is considerable and of equivalent magnitude to that associated with chronic medical conditions. This reduction in physical functioning associated with the presence of mood disorders was equivalent to that associated with being some 12 years older. In contrast, chronic medical conditions only had a modest impact on mental functioning.

Related studies

These results are based upon use of the SF–36, an instrument derived from the Medical Outcomes Study, which is probably the most widely used, reliable and valid generic measure of subjective health status and is recognised to provide useful information not identified in routine clinical evaluations (Reference Brown, Melville and GrayBrown et al, 1999). The Medical Outcomes Study of over 11 000 out-patients attending primary care facilities in the USA (Reference Wells, Stewart and HaysWells et al, 1989) reported that the functioning and well-being of patients with depression were comparable with or worse than those uniquely associated with eight major medical conditions, with subsequent work extending findings through the study of groups of patients drawn from other cultures (Reference Ormel, Vonkorff and UstunOrmel et al, 1994). Prolonged follow-up of patients meeting the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder has shown the clinical course to be characterised by periods of sustained symptomatic disability (Reference Surtees and BarkleySurtees & Barkley, 1994), by increased risk of suicide and to be a risk factor for the onset of physical and psychosocial disability (Reference Judd, Akiskal and ZellerJudd et al, 2000). Further evidence has documented the chronicity associated with the clinical course of generalised anxiety disorder, represented by the limited likelihood (at 25%) of symptomatic remission after a 2-year episode and role impairment equivalent to that of major depressive disorder (Reference Yonkers, Warshaw and MassionYonkers et al, 1996; Reference Kessler, DuPont and BerglundKessler et al, 1999).

Study limitations

Participants in EPIC–Norfolk were recruited by post, through general practice age–gender registers, except those identified as unsuitable (e.g. owing to terminal illness) by the general practitioner (Reference Day, Oakes and LubenDay et al, 1999). Because participation in EPIC–Norfolk included a request for detailed biological, dietary and other data, and because follow-up would continue over a number of years, around 45% of eligible participants were recruited to the study and therefore did not represent a truly random sample of the population. However, the EPIC–Norfolk cohort is representative of the general resident population of England in terms of anthropometric variables, blood pressure and serum lipids, but has fewer current smokers (Reference Day, Oakes and LubenDay et al, 1999).

This study defined chronic physical disease to include cancer, diabetes, myocardial infarction and stroke. In consequence, our ‘disease-free’ comparison population will have included study participants with other conditions (including angina, arthritis, chronic bronchitis, hypertension, osteoporosis) perhaps likely to have contributed to underestimation of group differences in functional status. However, such bias is likely to have been minimal in the context of the size of the study population.

In addition, there may be some misspecification in the diagnosis of both major depressive disorder and generalised anxiety disorder in this study. However, the structured self-assessment approach adopted in the HLEQ represents a pragmatic solution to enabling measures of emotional state, representative of core DSM–IV diagnostic criteria, to be included in a large-scale chronic disease epidemiology project. Previous work has demonstrated that prevalence estimates and age–gender distributions of major depressive disorder derived from this approach are comparable to those from interview-based assessments from UK and international studies (Reference Surtees, Wainwright and BrayneSurtees et al, 2000).

Although this study perhaps provides a unique perspective on the extent to which a large middle-aged and older community-dwelling UK population report levels of impairment in their health status, according to the SF–36 (associated with chronic medical conditions and mood disorders) the results are based upon a cross-sectional analysis and therefore provide no insight into the direction of effects. However, findings from longitudinal patient-based studies have shown that pre-existing depression is a risk factor for the onset of objective measures of disability (Reference Penninx, Guralnik and FerrucciPenninx et al, 1998), that effective treatment of depression improves health-related quality of life (Reference Wells, Sherbourne and SchoenbaumWells et al, 2000) and that functional limitations predict the onset and worsening of depression (Reference Prince, Harwood and ThomasPrince et al, 1998). These findings have led some (Reference OrmelOrmel, 2000) to conclude that the association between depression and disability is likely to be due to bi-directional effects among depression, physical limitations and psychosocial disability, with this being particularly so in older people.

Implications of the findings

Our results suggest that chronic anxiety is associated with physical functional health status limitations in excess of those associated with either chronic depression or any of the physical health conditions considered, except for stroke. These findings complement other evidence concerning levels of impairment associated with generalised anxiety disorder (Reference Kessler, DuPont and BerglundKessler et al, 1999). Additionally they provide a UK population perspective on the impact of mood disorders on functional health status relative to chronic disease, most usually examined in the context of patient groups and with a focus on depression (Reference Wells, Stewart and HaysWells et al, 1989). Major (unipolar) depression has been reported (Reference Murray and LopezMurray & Lopez, 1996) to be responsible for more than 1 in every 10 years of life lived with a disability worldwide, with projections that by the year 2020 depression will be the second most important determinant of global disease burden, which is a larger proportionate increase from 1990 than that for the cardiovascular diseases. Chronic disabling medical and emotional conditions consume a substantial part of curative health service resources and, as this study has suggested, combine to impair functional status. With compelling evidence for the effective treatment of mood disorders having an associated benefit in terms of improved physical capacities, further research is needed on the prevention and management of mood states (particularly in general practice), including those comorbid with physical disease. Such research would need to address the realistic primary care concerns over mood disorder detection, treatment effectiveness, patient compliance with treatment and the use of diagnostic criteria for depression developed in secondary care (Reference KendrickKendrick, 2000), together with further evaluation of care models designed to map the duration of intervention to condition chronicity (Reference Rost, Nutting and SmithRost et al, 2002).

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ In this large community-dwelling population, a history of chronic medical conditions was associated with only a modest impact on mental functional health status, whereas prevalent mood disorders were associated with a profound impact on physical functional status.

-

▪ The degree of physical functional impairment associated with mood disorders was of equivalent magnitude to that associated with the presence of chronic medical conditions or with being some 12 years older.

-

▪ Comorbidity of chronic medical conditions and prevalent mood disorder was associated with additional impairment in self-reported physical but not mental functional status beyond that associated with the presence of only one condition.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Results are based upon a cross-sectional analysis and therefore provide no insight into the direction of effects.

-

▪ Participants were not a random sample of the population but we doubt that this is a source of significant bias. Other work has shown the study population to be representative of the general resident population of England in terms of anthropometric, lifestyle and biological variables.

-

▪ Differences in functional status between those with and without any of the defined chronic medical conditions may have been underestimated owing to other conditions being prevalent in the group defined as ‘disease-free’. However, we believe that such bias is likely to have been minimal in the context of the size of the study population.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and general practitioners who took part in this. study and the staff associated with the research programme. EPIC–Norfolk. is supported by programme grants from the Cancer Research Campaign and the. Medical Research Council, with additional support from the Stroke Association, the British Heart Foundation, the Department of Health, the Food Standards. Agency, the Wellcome Trust and the Europe Against Cancer Programme of the. Commission of the European Communities.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.