This work of far more than biography should be obligatory reading for psychiatrists under 50 and psychoanalysts of any age, whether psychiatrists too or not. This is not just the story of one man but a work of scholarship concerning the psychoanalytic community in post-1945 Britain and France, and dominating North American psychiatry until the century ended, yet now outside the experience of most psychiatrists under 50. They are not only deprived of a fascinating epoch recently in their field but more limited in vision by that than they may realise.

Unintentionally, Linda Hopkins, a psychologist and psychoanalyst, has given us the most detailed study from cradle to grave, at 65, of a case of borderline personality disorder, often called psychopathic personality. Unfortunate parenting – a father of 73, a teenage mother (the latest of 4 wives) and 9 sons, in his colonial India ménage, of peasant stock, made a beriched landowner in reward for service in the British Empire. His father allowed little Masud to witness his mother's convulsive delivery of a stillborn fetus, which left him with mutism for 3 years to follow, depressive recurrences ever afterwards, an adult lifestyle of self-aggrandising postures, delinquent mendacity, near misses of prison, grossly disordered sexuality, destructiveness, and finally paranoia and suicidal alcoholism.

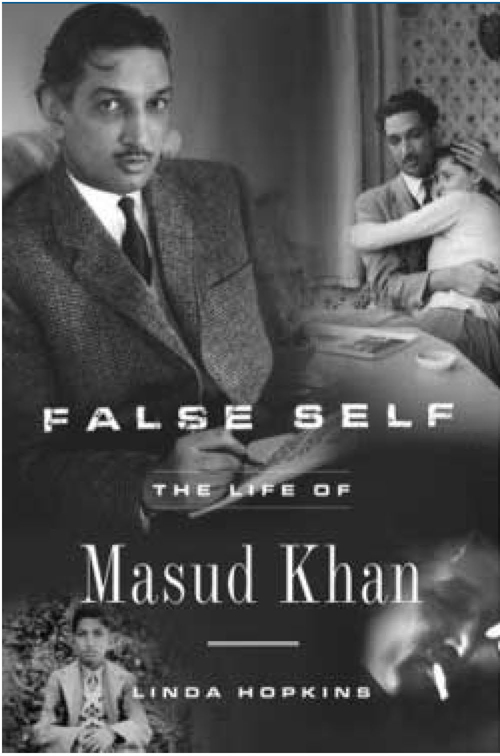

The author's miracle is contriving to leave one with a poignant sense of tragedy. Khan was all these things, yet prodigiously gifted – in intellectual productivity, in scaling the heights of the artistic and social worlds of the West, attaining clinical summits, international recognition, and prodigious too as self-inventor, impostor, sexual marauder of patients. The mountain of his daily writings are said to yield riches. Meanwhile, the British Psychoanalytic Society has embargoed their study until 2039!

Khan's father died leaving him wealthy at 20. By 1946, aged 22, he arrived in Britain with 27 suitcases, a chauffeur-driven Rolls Royce, and an MA of which the thesis in its only copy was lost by T. S. Elliot. With no education in medicine or psychology, he was accepted for training in psychoanalysis. He was quickly elevated to training analyst in 1959, a rare accolade, soon to be guest lecturer at major American psychiatric centres, and even a drunken one once at a Royal College of Psychiatrists' conference. Later, he became foreign editor of the Nouvelle Revue Française de Psychanalyse, editor of the International Psychoanalytic Library, and a director of Freud Copyrights.

But this was not all – far from it. He married and ruined the lives of two of the most precious stars in ballet, acquired a magnificent library and French paintings. Linda Hopkins has reminded us through a living example of how psychoanalysis attracts gifted, potentially creative people, and how the frontier between creativity and psychopathology is an insecure one. The eternal question which goes far beyond how to recruit for psychoanalysis, psychiatry, psychology, is how to distinguish the two anywhere and in whatever field.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.