Rates of involuntary placement or treatment of people with mental illness are widely considered to be an indicator for underlying characteristics of national mental health care laws or other legal frameworks. Unfortunately, despite the growing international mental health law debate, sound data on the international practice of compulsory admission are scarce (Reference Riecher-Rössler and RösslerRiecher-Rössler & Rössler, 1993). Most of the few published international comparisons in this area include only selected nations (Reference Laffont and PriestLaffont & Priest, 1992; Reference LegemaateLegemaate, 1995; Reference van Lysbetten and Igodtvan Lysbetten & Igodt, 2000). Findings suffer from reduced availability and reliability of data. Varying definitions or methods adopted by national health departments or statistical bureaus contribute to sometimes dramatic differences in compulsory admission rates or quotas (Reference Riecher-Rössler and RösslerRiecher-Rössler & Rössler, 1993). Time series are especially scarce. When available, strong changes over time seem to indicate that rates or quotas are subject to a broad set of influencing factors, including changing legal frameworks, varying administrative routines and differences in quality standards of national or regional mental health care systems (Reference Miller and FiddlemanMiller & Fiddleman, 1983; Reference EngbergEngberg, 1991; Reference KokkonenKokkonen, 1993; Reference LecompteLecompte, 1995; Reference KjellinKjellin, 1997; Reference Wall, Hotopf and WesselyWall et al, 1999; Reference de Girolamo and Cozzade Girolamo & Cozza, 2000).

In the search for predictive factors for compulsory admission rates, some socio-demographic characteristics have been identified as increasing the risk of being placed involuntarily (Reference Gove and FainGove & Fain, 1977; Reference Mahler and CoMahler & Co, 1984; Reference Dunn and FahyDunn & Fahy, 1990; Reference Davies, Thornicroft and LeeseDavies et al, 1996; Reference Sanguineti, Samuel and SchwartzSanguineti et al, 1996; Reference Singh, Croudace and BeckSingh et al, 1998; Reference Crisanti and LoveCrisanti & Love, 2001), although some of the findings are contradictory (Reference Szmulker, Bird and ButtonSzmulker et al, 1981; Reference NicholsonNicholson, 1988; Reference Tremblay, King and BainesTremblay et al, 1994). All in all, the scarcity of data and the variety of controversial research results may be attributed to a complex set of poorly understood legal, political, economical, social, medical, methodological and other factors interacting in the process. Rapid European integration requires valid overviews and a sound database for increased research concerning this most controversial and important issue.

METHOD

The European Commission funded a study for gathering and analysing information on the differences or similarities of legal frameworks for involuntary placement or treatment of mentally ill patients across the European Union (EU) member states, and the outcome in terms of involuntary admission rates to psychiatric facilities. The study was conducted from November 2000 to January 2002. By definition, involuntary placement or treatment in this study excluded any aspect of placement or treatment of mentally ill offenders or any other aspect of forensic psychiatry. Mentally ill offenders were seen as a clearly distinct population and an issue of greater complexity, requiring different legal frameworks and placement or treatment strategies. Legal regulations for placement and treatment of mentally ill offenders are currently being evaluated by another study, also funded by the European Commission.

Information on the legislation and practice of involuntary placement and treatment in the EU states was gathered by means of a detailed questionnaire. This questionnaire included 80 items addressing four main areas: legislation, practice, patients' rights and epidemiology. It covered aspects such as criteria for compulsory admission, procedures of decision-making, time frames, regulations for compulsory treatment or other coercive measures, quality assurance aspects, complaint procedures and epidemiological data. A draft of the questionnaire was evaluated and revised by a core group of experts before distribution, and tested in a pilot study in Germany. The final version of the questionnaire was filled in by selected experts (psychiatrists) from all EU member states. An expert meeting to discuss the preliminary results was held in Germany in November 2001. Experts were asked to collect epidemiological data from official sources (national health reports, statistical bureaus, etc.), thus relying on the definitions of terms such as ‘episode’, ‘preliminary detention’ and ‘compulsory admission’.

RESULTS

The results presented here focus on a comparison of most recent national compulsory admission data from all EU member states, including time series for the 1990s when available.

Availability of data

Experts from five countries reported the absence of an official institution or agency responsible for gathering or providing nationwide data on compulsory admission numbers or rates at the time of the study (Austria, Germany, Greece, Italy and Spain). Some countries do record such data, although it may not be available to the public, as in Belgium. In some other countries, nationwide registers were implemented only recently (e.g. Portugal). Most of the data in our study were taken from these agencies or institutions, in some cases supplemented by information from other sources. In detail, data were obtained from Belgium (national and regional departments), Denmark (Danish Psychiatric Case Register, Århus University and the National Board of Health), Finland (National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health (STAKES)), France (Ministère Chargé de la Santé), Ireland, (Health Board), The Netherlands (Geeste-lijke Gezondheidszorg Nederland, Utrecht), Luxembourg (Department of Health), Portugal (Commission for the Supervision of the Mental Health Law), Sweden (National Board of Health and Welfare) and the United Kingdom (Department of Health). In the case of Austria, data were requested from the Ministry of Health. The German Department of Justice provided the number of applications for involuntary placements, owing to the unavailability of information on legally confirmed compulsory admissions. From Italy, selected regional data for the province of Lombardy were forwarded. For Greece and Spain, epidemiological data were completely unavailable.

Frequency of compulsory admission

Table 1 shows the most recently available national data on frequency and percentages of involuntary placements of people with mental disorder across the EU. Total numbers differ considerably, but there are also remarkable differences in commitment rates (annual number of compulsory admissions per 100 000 population) and quotas (percentage of all psychiatric admissions), which are more appropriate for comparing indicators between countries.

Table 1 Rates of involuntary placements for mental disorder in European Union countries

| Country | Year | Involuntary placements | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percentage of all in-patient episodes | Per 100 000 population | ||

| Austria | 1999 | 14 122 | 18 | 175 |

| Belgium1 | 1998 | 4799 | 5.8 | 47 |

| Denmark1 | 2000 | 1792 | 4.6 | 34 |

| Finland | 2000 | 11 270 | 21.6 | 218 |

| France | 1999 | 61 063 | 12.5 | 11 |

| Germany2 | 2000 | 163 551 | 17.7 | 175 |

| Greece | Not available | Not available | Not available | |

| Ireland | 1999 | 2729 | 10.9 | 74 |

| Italy | Not available | 12.13 | Not available | |

| Luxembourg | 2000 | 396 | Not available | 93 |

| The Netherlands | 1999 | 70004 | 13.2 | 44 |

| Portugal | 2000 | 618 | 3.2 | 6 |

| Spain | Not available | Not available | Not available | |

| Sweden | 1998 | 10 104 | 305 | 114 |

| United Kingdom6 | 1998 | 46 300 | 93 | |

| 1999 | 23 822 | 13.5 | 48 | |

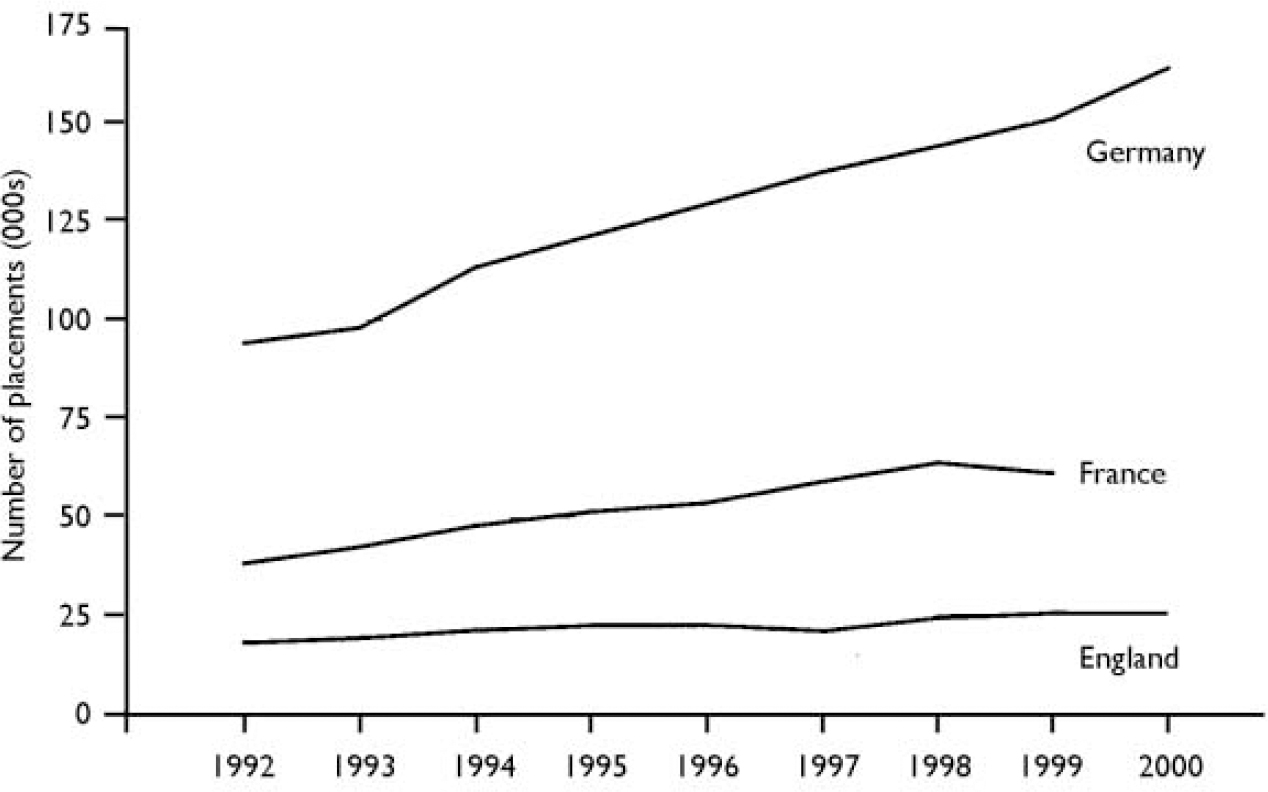

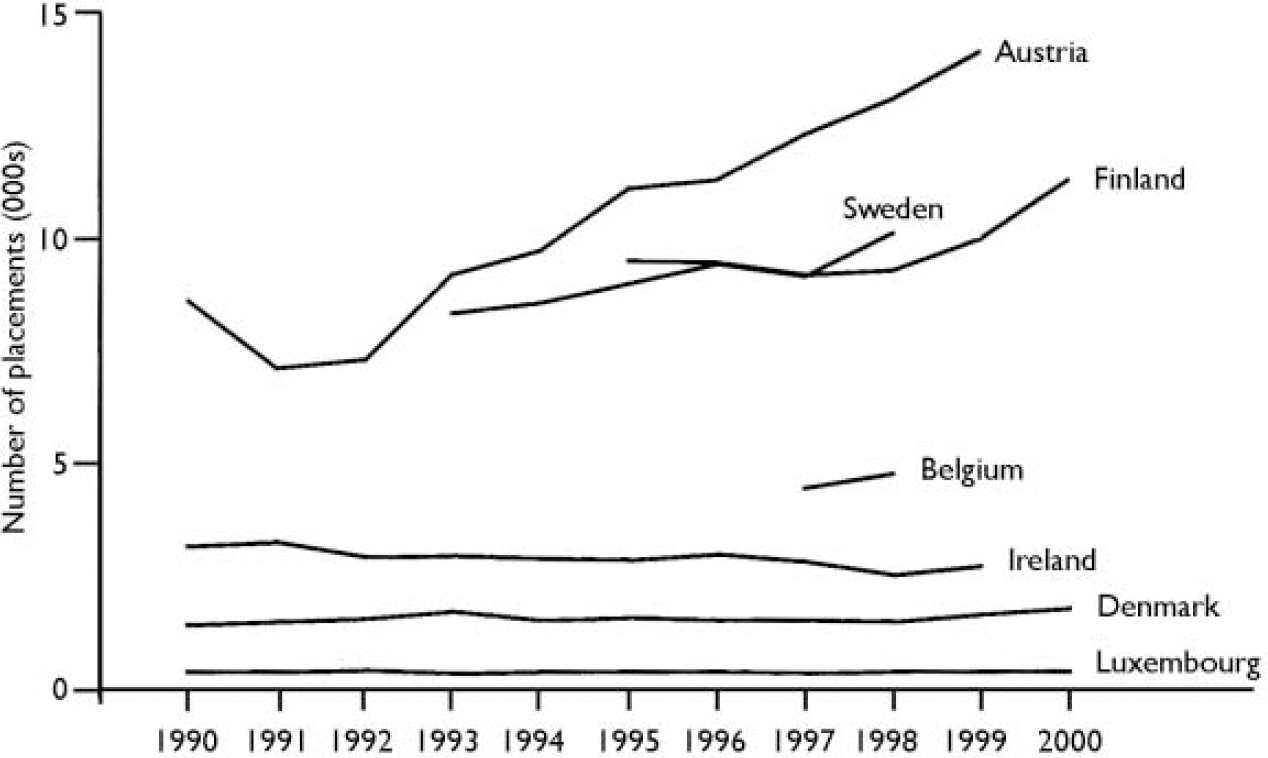

In addition, time series for involuntary placements during the past decade were assessed. The availability of these data were better than expected. Only Greece, Italy and Spain were unable to provide nationwide data from the 1990s. Contributions from Belgium and Portugal cover only short periods from the late 1990s, and all other states provided continuous annual frequencies. Not surprisingly, France, Germany and the UK, being the most populous countries, reported the most frequent involuntary placements. These series are displayed using separate scales (Figs 1 and 2).

Fig. 1 Frequency of involuntary placements during the 1990s in the most populous European Union member states.

Fig. 2 Frequency of involuntary placements during the 1990s in the smaller European Union member states.

Total annual frequencies are presented here to demonstrate national trends over time and might be appropriate for analysing changes in policies within a particular country. For comparisons between countries, weighted data as percentages of involuntary placements on all psychiatric admissions (quotas) must be used (Table 2). Despite reduced reliability or validity in some cases, time series suggest that in most member states involuntary placement quotas have remained more or less stable during the past decade, or even have decreased in some countries. This finding is in contrast to the increasing numbers of involuntary placements as shown in Figs 1 and 2, and does not confirm an overall trend of increasing compulsory admissions.

Table 2 Involuntary placements as a percentage of all psychiatric in-patient episodes

| Involuntary placements (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | |

| Austria | 17 | 20 | 21 | 23 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 18 | |||

| Belgium | 5.5 | 5.8 | |||||||||

| Denmark | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.6 |

| Finland | 21.5 | 20.5 | 19.9 | 19.4 | 20.7 | 21.6 | |||||

| Ireland | 11.5 | 11.7 | 10.9 | 11 | 11 | 10.8 | 11.2 | 11 | 10.2 | 10.9 | |

| Luxembourg1 | 36 | 31.4 | 31 | 29 | 28.8 | 31.1 | 31.1 | 27 | 26.4 | ||

| The Netherlands2 | 13.4 | 12.6 | 15.7 | 14.6 | 14.6 | 14.5 | |||||

| Portugal | 2.8 | 3.2 | |||||||||

| England | 9.2 | 9.2 | 9.8 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.01 | 12 | 13.6 | 13.5 | ||

| Germany | 13.5 | 14 | 14.2 | 14.9 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 15.9 | ||||

Correlation with procedural features

Certain procedural regulations from the variety of assessed characteristics of national laws (qualitative data) were selected to analyse possible correlations with compulsory admission rates or quotas (Table 2). Among these characteristics, the legally defined set of conditions required for compulsory detention or treatment is a major feature. Although the laws of all EU member states stipulate a confirmed mental disorder as a major condition for detention, additional criteria are heterogeneous. Threatened or actual danger to oneself or to others is the most common additional criterion across the EU, but is not a prerequisite in Italy, Spain or Sweden. Among countries stipulating the need for treatment (the second most common criterion), Denmark, Finland, Greece, Ireland, Portugal and the UK consider the danger criterion to be sufficient on its own. Some countries emphasise a lack of insight by the patient, additionally. No significant correlation could be identified with compulsory admission quotas or rates when comparing countries applying the ‘danger’ or ‘need for treatment’ criterion.

In ten member states, the final decision on involuntary placement is made by a non-medical authority, either a representative of the legal system (judge, prosecutor, mayor) or another agency independent of the medical system. In the remaining member states the decision is left to psychiatrists or other health care professionals (Table 3). Compulsory admission quotas and compulsory admission rates did not differ significantly between these countries.

Table 3 Procedural regulations for compulsory admission in European Union member states

| Country | Essential legal criteria for detention (additional to mental disorder) | Deciding authority for detention order | Mandatory inclusion of patient counsel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Danger | Non-medical | Yes |

| Belgium | Danger | Non-medical | Yes |

| Denmark | Danger or need for treatment | Medical | Yes |

| Finland | Danger or need for treatment | Medical | No |

| France1 | Danger | Non-medical | No |

| Germany | Danger | Non-medical | No |

| Greece | Danger or need for treatment | Non-medical | No |

| Ireland | Danger or need for treatment | Medical | Yes |

| Italy | Need for treatment | Non-medical | No |

| Luxembourg | Danger | Medical | No |

| The Netherlands | Danger | Non-medical | Yes |

| Portugal | Danger or need for treatment | Non-medical | Yes |

| Spain | Need for treatment | Non-medical | No |

| Sweden | Need for treatment | Medical | No |

| United Kingdom | Danger or need for treatment | Non-medical or medical | No |

The mandatory notification of relatives or other persons in case of a compulsory admission is a basic civil right. According to the laws of six member states, notification or inclusion of a legal representative of the patient (e.g. advocate, counsellor or social worker) into the procedure is mandatory. Member states with obligatory inclusion of a legal representative showed significantly lower compulsory admission quotas (P=0.03, Mann-Whitney U-test) and a trend towards lower compulsory admission rates (P=0.14, Mann-Whitney U-test).

Mental disorders and socio-demographic characteristics of detained patients

A third of the EU member states were able to provide diagnostic profiles of involuntarily placed persons. Despite a non-standardised usage of diagnostic categories, the specified mental disorders might provide a rough indicator of which patient groups are given priority for involuntary placement in the various countries. The largest group being admitted involuntarily are people with severe and chronic mental disorders such as schizophrenia or other psychoses, accounting for 30-50% of all involuntary placements in states that provided diagnostic data (Table 4). The proportions of groups with other diagnoses, such as dementia, affective disorders or substance misuse, differ remarkably. The occurrence in the table of conditions other than these most severe mental disorders is remarkably frequent. Unfortunately, details for these remaining patient groups (type of disorder, severity) were not available.

Table 4 Distribution of mental disorders and gender among compulsorily admitted people in European Union member states

| Year | Mental disorder | Proportion of all involuntary placed persons (%) | Proportion of males (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium1 | 1998 | Psychosis | 34.9 | 68.8 |

| Substance misuse | 24.5 | |||

| Affective disorder | 12.6 | |||

| Dementia | 2.2 | |||

| Finland | 1999 | ICD–10 F0 | 6.1 | 52.1 |

| ICD–10 F1 | 16.0 | |||

| ICD–10 F2 | 52.7 | |||

| ICD–10 F6 | 2.8 | |||

| France2 | 1997–1998 | ICD–10 F1 | 12.6 | 69 |

| ICD–10 F2 | 50.0 | |||

| ICD–10 F3 | 12.5 | |||

| ICD–10 F6 | 10.6 | |||

| ICD–10 F7 | 2.9 | |||

| Ireland | 1999 | Schizophrenia | 33.7 | 61.4 |

| Other psychosis | 3.7 | |||

| Organic psychosis | 3.3 | |||

| Mania | 13.7 | |||

| Depression | 13.0 | |||

| Alcoholism | 12.3 | |||

| Personality disorder | 7.0 | |||

| The Netherlands | 1997 | Schizophrenia | 29.5 | 68.5 |

| Affective disorder | 9.2 | |||

| Organic psychosis | 8.7 | |||

| Drug related | 5.2 | |||

| Personality disorder | 9.1 | |||

| Denmark | 2000 | Not available | 52.2 | |

| Luxembourg | 2000 | Not available | 62.7 | |

| United Kingdom3 | 1999 | Not available | 50.9 | |

| Austria, Germany, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain | Not available | Not available |

Information about the socio-demographic characteristics of involuntarily admitted patients is as scarce as the psychopathological background information. Even the most basic gender data were available from only nine countries, five of which showed a tendency to place male patients more often involuntarily than females (Belgium, France, Ireland, Luxembourg and The Netherlands; Table 4). An overrepresentation of male patients might serve as a rough indicator that danger is the prime consideration in involuntary placement, since men with mental illness reportedly are more likely than women to show dangerous behaviour. However, for a valid comparison, the proportion of compulsorily admitted males should have been tested against the proportion of total admissions of males to psychiatric in-patient care in each country. Unfortunately, these data were not available.

DISCUSSION

Validity and reliability of data

This study tried to assess and compare data on the involuntary placement or treatment of mentally ill patients in all EU member states in a structured approach. Despite surprisingly complete contributions and replies from almost all member states, reliability and validity of data are still imperfect, owing to non-standardised definitions of concepts or data recording methods. For example, some countries might apply different definitions or concepts of compulsory admission; some might register a patient's change from a voluntary to an involuntary treatment regimen (or vice versa) during the same period of admission, whereas others might not. We tried to control the data presented here for these modalities, but could not completely rule out inconsistencies. Thus, data assessed by this study may be confounded in several ways, and conclusions about national approaches or mental health policies must be drawn cautiously. Nevertheless, because of the shortage of sound research in this field, our results may represent the most comprehensive overview of the current situation in the EU.

Trends in compulsory admission rates

Whereas variations in the frequencies of annual compulsory admissions of people with mental illness are not surprising in view of the different population sizes of EU countries, compulsory admission rates (annual admissions per 100 000 population) vary remarkably, too. Rates ranging from a mere 6 annual compulsory admissions per 100 000 population in Portugal to 218 in Finland (see Table 1) strongly hint at differences in definitions, legal backgrounds, or procedures. Comparison of the time series of compulsory admission quotas during the past decade reveals a slightly more homogeneous pattern, suggesting an overall tendency towards more or less stable quotas in most countries (see Table 2). This finding contradicts conclusions indicating an overall international trend towards increasing numbers of compulsory admissions. Similar assumptions might arise from this study too if compulsory admissions are considered in isolation, as total numbers were found to be increasing in Germany, France, England, Austria, Sweden and Finland (see Figs 1 and 2). However, the increasing number of compulsory admissions seems to be balanced by the effects of internationally changing patterns of mental health care delivery, which shortens the mean length of in-patient stay at the expense of more frequent readmissions.

The finding of significantly lower compulsory admission quotas in member states stipulating the inclusion of an independent counsel into the procedure suggests further analyses. At the moment it can only be postulated that better legal support for patients might contribute to lower compulsory admission rates or quotas, since we are not able to control for the real number of patients who are compulsorily detained without any legal representation.

Diagnostic and socio-demographic profiles of involuntarily placed patients

The limited data on diagnostic patterns or socio-demographic characteristics of compulsorily admitted patients submitted by some EU member states also suggest further analyses. Overall, schizophrenia and related disorders seem be the predominant diagnosis in countries that were able to provide diagnostic overviews, without giving a clear hint as to a correlation with any legal or procedural approach. However, analysis of the gender of compulsorily admitted patients indicates that countries preferring the ‘danger’ criterion appear to place more male patients involuntarily than female. This pattern might reflect general findings that mentally ill men are more violent, and thus are selected more frequently for compulsory admission when the ‘danger’ criterion is applied. Whether this result indicates any real influence of the criteria on the gender of compulsorily admitted populations has to be confirmed in further analyses, through controlling the proportion of compulsorily admitted men by the overall gender proportion of psychiatric in-patients in the respective EU member states.

Consequences for health reporting

All in all, results of this study show the strong necessity for further research in this field. Internationally standardised and annually updated involuntary placement rates on a national level (detailing a number of basic items, such as regular or emergency admission as well as socio-demographic and diagnostic characteristics) are fundamental to the evaluation of national as well as Europe-wide policies. The improvement of common international standards of mental health reporting seems to be essential, at least within the EU, to guarantee valid overviews for the future and provide a basis for more detailed research in the field.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ This study reports data from all European Union (EU) member states that will contribute to the increasingly international dimension of the mental health law debate.

-

▪ Time series on compulsory rates and quotas for the 1990s are given for most of the EU member states.

-

▪ The study shows obstacles to future harmonisation of legislation and practice across the EU.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Varying the inclusion criteria or concepts for involuntary placement might confound findings (e.g. inclusion or exclusion of short-term detentions, emergency procedures or changes from voluntary to involuntary status during in-patient episodes).

-

▪ The set of legal, political, economic, social, medical, methodological and other factors interacting in the process of involuntary placement or treatment of people with mental illness is complex and still poorly understood.

-

▪ The lack of socio-demographic and psychopathological details for compulsorily detained populations prevents further analysis.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a grant from the Health and Consumer Protection. Directorate-General of the European Commission. Data were provided by experts. from the European Union member states, for whose valuable contribution we are. grateful: Peter König (Rankweil, Austria); Jutta Knoerzer (Vienna, Austria); Marc de Hert, Maurits Demarsin, Jozef Peuskens (Kortenberg, Belgium); Helle Aggernaes (Copenhagen, Denmark); Rittakerttu Kaltiala-Heino (Tampere, Finland); Viviane Kovess, C. Jonas, A. Machu (Paris, France); George. N. Christodoulou, Basil Alevizos, Athanassios Douzenis (Athens, Greece); Dermot Walsh (Dublin, Ireland); Mauro G. Carta (Cagliari, Italy); Maria Hardoy (Florence, Italy); Charles Pull, Jean-Marc Cloos (Luxembourg); Jean-Marie. Spautz, Romain Thillman (Ettelbruck, Luxembourg); William J. Schudel (The. Hague, The Netherlands); Miguel Xavier (Lisbon, Portugal); Francisco. Torres-González (Granada, Spain); Karl-Otto Svärd (Karlstadt, Sweden); David V. James (London, UK).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.