Most patients with depressive symptoms do not reach the minimum diagnostic criteria for major depression, and are described as having minor or subsyndromal or subthreshold depression. 1 For subthreshold depression, different definitions based on the number of depressive symptoms, duration of symptoms, exclusion criteria and associated functional impairment have been proposed. Reference Pincus, Davis and McQueen2 Judd and colleagues defined the category subsyndromal symptomatic depression as ‘any two or more simultaneous symptoms of depression, present for most or all of the time, at least two weeks in duration, associated with evidence of social dysfunction, occurring in individuals who do not meet criteria for diagnoses of major depression and/or dysthymia’. Reference Judd, Rapaport, Paulus and Brown3,Reference Ayuso-Mateos, Nuevo, Verdes, Naidoo and Chatterji4

The public health importance of minor depression has been highlighted, with reported rates varying according to the definition used: 2.5–9.9% in community samples or 5–16% in primary care patients. Reference Judd, Rapaport, Paulus and Brown3,Reference Rucci, Gherardi, Tansella, Piccinelli, Berardi and Bisoffi5,Reference Veerman, Dowrick, Ayuso-Mateos, Dunn and Barendregt6 Minor depression is associated with psychological suffering, significant decrements in health, significant impairment in daily living activities and with a considerable impact on quality of life. Reference Preisig, Merikangas and Angst7–Reference Kessler, Zhao, Blazer and Swartz10 Minor depression is also a strong risk factor for major depression, which develops in 10–25% of patients with subthreshold depression within 1–3 years. Reference Cuijpers and Smit11 Additionally, minor depression might increase the risk of death in older individuals. Reference Penninx, Geerlings, Deeg, van Eijk, van and Beekman12

Under ordinary circumstances, patients with depressive symptoms, but not major depression or dysthymia, have been frequently treated with antidepressants and benzodiazepines. Reference Esposito, Wang, Adair, Williams, Dobson and Schopflocher13–Reference Valenstein, Taylor, Austin, Kales, McCarthy and Blow18 In the province of Alberta, Canada, for example, more than 67% of a community sample of individuals receiving antidepressants did not have any psychiatric diagnosis, but reported, as the main reasons for taking these medicines, depressive symptoms, stress, sleep problems, anxiety or headache. Reference Esposito, Wang, Adair, Williams, Dobson and Schopflocher13 In Europe, a cross-sectional population-based study conducted in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands and Spain found that nearly 10% of individuals without any episode of major depression currently used either or both antidepressants and benzodiazepines. In this study, seeking help for emotional problems appeared to be a more important predictor for the use of antidepressants or benzodiazepines than a formal diagnosis of major depression. Reference Demyttenaere, Bonnewyn, Bruffaerts, De Girolamo, Gasquet, Kovess and Haro14

The use of antidepressants and benzodiazepines in minor depression has been explored by narrative reviews that concluded that antidepressants may have a small to moderate benefit in patients with this condition, Reference Ackermann and Williams19,Reference Oxman and Sengupta20 and that benzodiazepines seem to have some effect on anxiety rather than depressive symptoms. Reference Birkenhager, Moleman and Nolen21 The literature searches of these reviews, however, were last updated in 2001, and therefore did not include studies published thereafter. In the present systematic review we sought to determine the efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological treatments for patients with minor depression.

Method

Criteria for inclusion in this review

Studies

This systematic review included only double-blind randomised controlled trials comparing the following treatment options for minor depression: (a) antidepressants v. placebo; and (b) benzodiazepines v. placebo. Quasi-randomised trials, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week, were excluded. For trials with a crossover design, only results from the first randomisation period were considered.

Participants

We included patients aged 18 or older, male and female, meeting criteria for minor/subthreshold depression according to the DSM, ICD, Research Diagnostic Criteria or any other standardised criteria. Studies that did not exclude the presence of major depression at study entry were not considered. We included studies in which individuals with major and minor depression were recruited, or studies in which individuals with dysthymia and minor depression were recruited, if the results were specifically reported for those with minor depression. Studies including individuals with minor depression and a serious concomitant medical illness were not considered. No language restrictions were applied.

Interventions

Active pharmacological treatments under study included the following.

-

(a) Antidepressants: tricyclic/heterocyclic, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram, paroxetine, escitalopram, sertraline), selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine, duloxetine, milnacipran, desvenlafaxine), monoamine oxidase inhibitors or newer agents (mirtazapine, bupropion, reboxetine, nefazodone, trazodone).

-

(b) Benzodiazepines: anxiolytic agents, hypnotics and sedatives.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures were the following.

-

• Group mean scores at the end of the trial, or group mean change from baseline to end-point, on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD), Reference Hamilton22 Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Scale (MADRS) Reference Montgomery and Åsberg23 or Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Reference Guy24 rating scale. When trials reported results from more than one rating scale, we used the HRSD results or, if not available, the MADRS results.

-

• Failure to respond to treatment: proportion of patients who failed to show a reduction of at least 50% on the HRSD or MADRS, or who did not score ‘much improved’ or ‘very much improved’ on the CGI, or proportion of patients who failed to respond using any other pre-specified criterion.

-

• Proportion of patients still with major depressive disorder at study end-point, as established with help of a standardised diagnostic interview.

-

• Proportion of patients leaving the study early for any reason – total drop-out rate.

Search methods for identification of studies

Literatures searches (last update: May 2009) were performed in the following databases and article indexes: MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, PsycInfo and Cochrane Controlled Trials Register. Controlled vocabulary was utilised where appropriate terms were available, supplemented with keyword searches to ensure accurate and exhaustive results. Search results were limited to randomised controlled trials or clinical trials (Phase III). Language or publication year limits were not applied to any search (online Appendix DS1).

To supplement the searches of published research, the internet was also utilised to locate additional clinical trials, unpublished research and/or grey literature. Websites of pharmaceutical companies, clinical trials, and medical control agencies were searched with a specific focus on clinical trial registries. Searched websites included: ClinicalTrials.gov, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Organon, Solvay, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pierre Fabre, Wyeth, US Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (Japan), and Therapeutic Goods Administration (Australia).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of trials

Included and excluded studies were collected following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; online Appendix DS2). Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman25 We examined all titles and abstracts, and obtained full texts of potentially relevant papers. Working independently and in duplicate, two reviewers read the papers and determined whether they met inclusion criteria. Considerable care was taken to exclude duplicate publications.

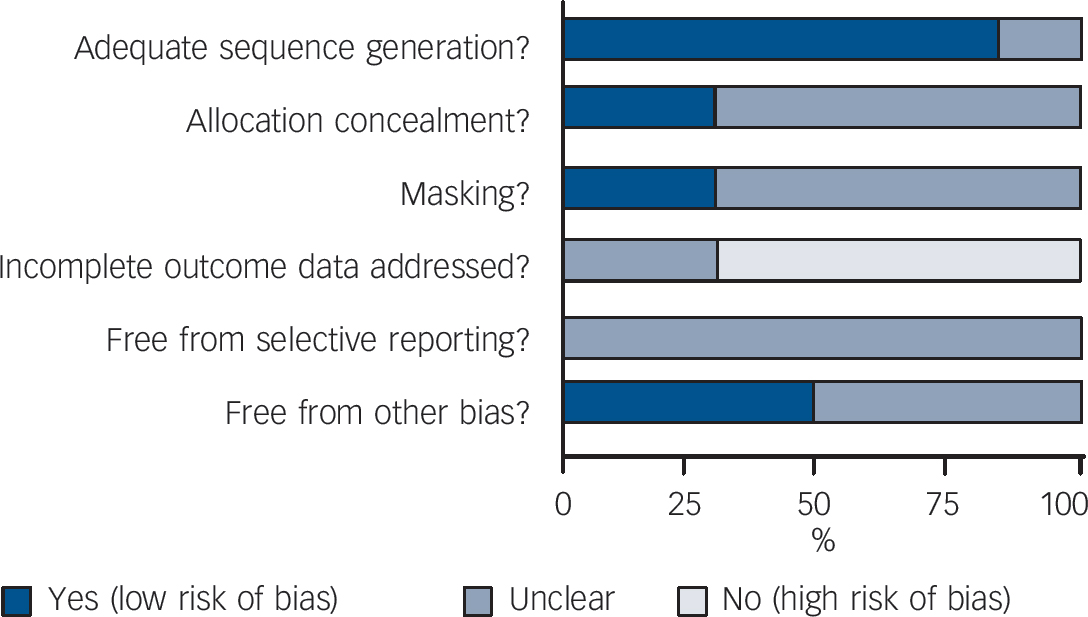

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The Cochrane risk-of-bias tool was used (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, England). This instrument consists of six items. Two items assess the strength of the randomisation process in preventing selection bias in the assignment of participants to interventions: adequacy of sequence generation and allocation concealment. The third item (masking) assesses the influence of performance bias on the study results. The fourth item assesses the likelihood of incomplete outcome data, which raises the possibility of bias in effect estimates. The fifth item assesses selective reporting, the tendency to preferentially report statistically significant outcomes. This item requires a comparison of published data with trial protocols, when such are available. The final item refers to other sources of bias that are relevant in certain circumstances such as sponsorship bias.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (C.B. and A.C.) independently extracted data concerning participant characteristics, intervention details and outcome measures. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus with a third member of the team.

For continuous outcomes, the mean change from baseline to end-point, the mean scores at end-point, the standard deviation or standard error of these values, and the number of patients included in these analyses were extracted. Reference Norman26 Data were extracted preferring the 17-item HRSD (over any other version of the HRSD) and over the MADRS and the CGI.

For dichotomous outcomes, the number of patients undergoing the randomisation procedure, the number of patients rated as responders and the number of patients leaving the study early were recorded.

Data analysis

A double-entry procedure was employed. Data were initially entered and analysed using the Cochrane Collaboration's Review Manager software version 5 for Windows (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, England), and subsequently entered into a spreadsheet and re-analysed using the ‘metan’ command of STATA 9.0 for Windows (STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). Outputs were cross-checked for internal consistency.

Continuous data were analysed using mean differences or standardised mean differences (when scores from different outcome scales were summarised) using the random effects model (with 95% confidence intervals, CI), as this takes into account any differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. Reference Higgins and Green27

Failure to respond to treatment was calculated on an intention-to-treat basis: individuals who dropped out were always included in this analysis. When data on these participants were carried forward and included in the efficacy evaluation (last observation carried forward), they were analysed according to the primary studies; when they were excluded from any assessment in the primary studies, they were considered as drug failures. For dichotomous outcomes, the relative risk (RR) was calculated based on the random effects model (with 95% CI).

When outcome data were not reported, trial authors were asked to supply the data. For continuous outcomes, when only the standard error was reported, it was converted into standard deviation according to Altman. Reference Altman and Bland28 When standard deviation and errors were not reported at end-point, the mean value of known standard deviations was calculated from the group of included studies according to Furukawa et al. Reference Furukawa, Barbui, Cipriani, Brambilla and Watanabe29 For dichotomous outcomes, in case of no response from study authors, we estimated the number of patients responding to treatment using a validated imputation method. Reference Furukawa, Cipriani, Barbui, Brambilla and Watanabe30,Reference Cipriani, Furukawa, Salanti, Geddes, Higgins and Churchill31

Visual inspection of graphs was used to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity. This was supplemented using I 2. This provides an estimate of the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance alone. Where the I 2 estimate is greater than or equal to 50%, we interpreted this as indicating the presence of high levels of heterogeneity. Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman32

Findings were summarised in a table according to the methodology described by the GRADE working group. Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Kunz, Vist, Falck-Ytter and Schunemann33,Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Vist, Kunz, Falck-Ytter and Alonso-Coello34

Results

Characteristics of included studies

The original searches yielded 719 papers potentially relevant for this review (Fig. 1). Of these, 686 were excluded because neither titles nor abstracts indicated that patients with minor depression were captured. The remaining 33 studies were retrieved for more detailed evaluation, and 6 met the review inclusion criteria Reference Barrett, Williams, Oxman, Frank, Katon and Sullivan35–Reference Sullivan, Katon, Russo, Frank, Barrett and Oxman45 (online Appendix 3 lists the 27 excluded studies). The main characteristics of the six studies are reported in online Table DS1. Three studies compared paroxetine with placebo, while fluoxetine, amitriptyline and isocarboxazid were studied in one study each. No studies were found comparing benzodiazepines with placebo. Only one study recruited more than 100 patients, and length of follow-up ranged between 6 and 12 weeks. Two studies were carried out in individuals aged 60 or older, and three studies recruited patients in primary healthcare settings. All six studies excluded patients with major depression. Three studies were not financially supported by pharmaceutical companies. The overall quality of included studies was graded as low (Fig. 2 and online Appendix 4). In particular, incomplete outcome data were not addressed in most studies.

Efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants versus placebo

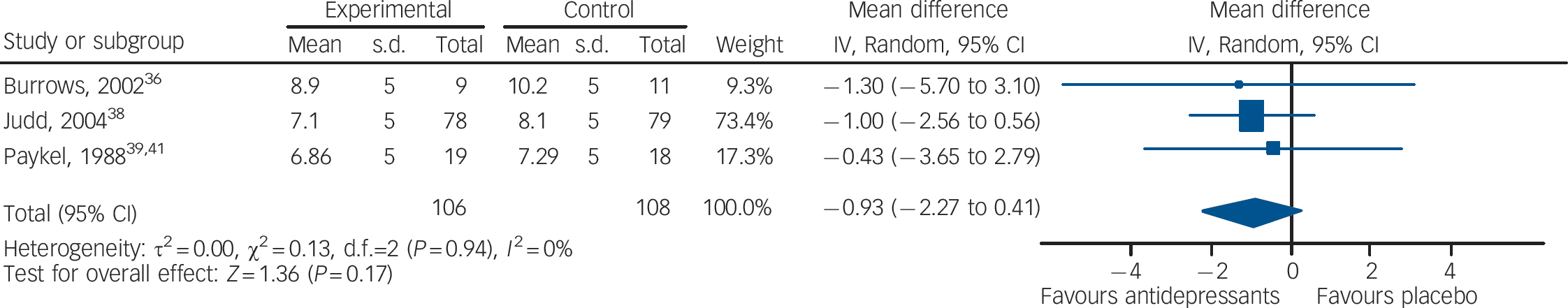

In terms of depressive symptoms, data extracted from three studies (106 patients treated with antidepressants and 108 with placebo) showed no statistically significant difference between antidepressants and placebo (mean difference –0.93, 95% CI –2.27 to 0.41) (Fig. 3). There was no statistically significant between-study heterogeneity.

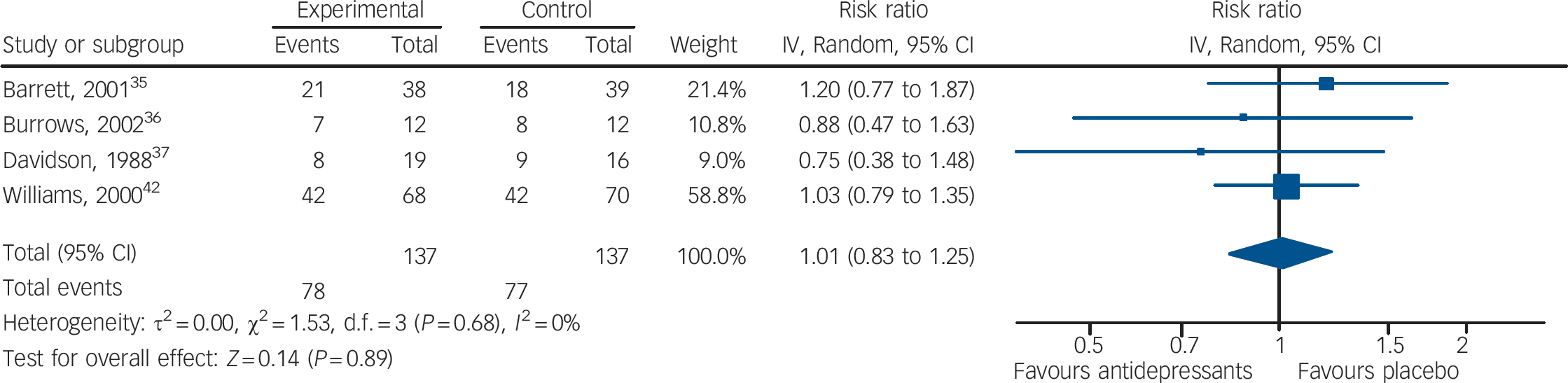

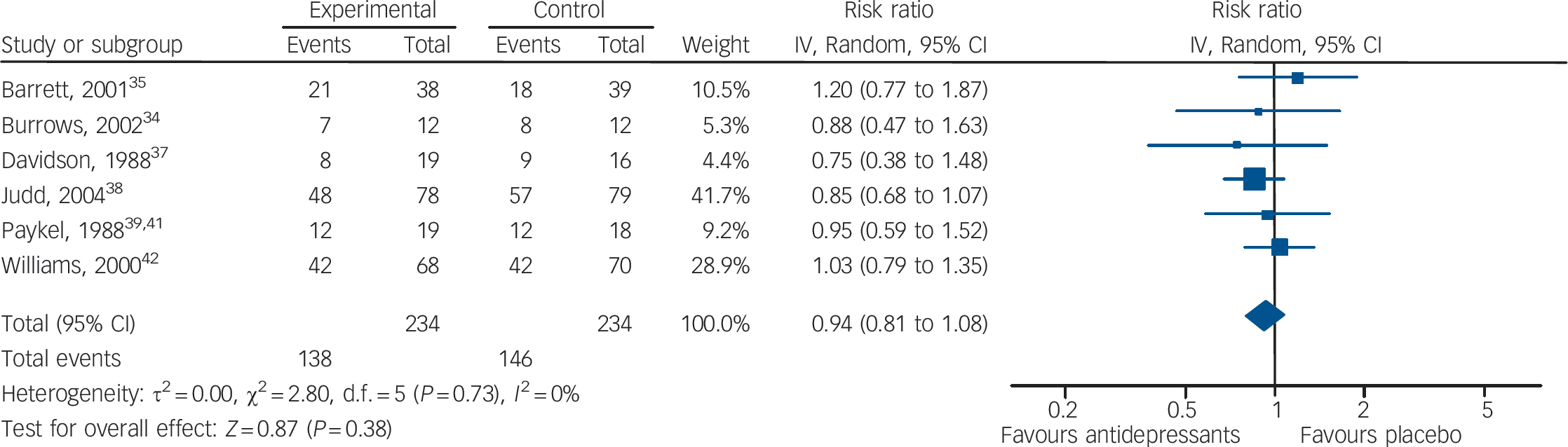

In terms of failures to respond to treatment, data extracted from four studies (137 patients treated with antidepressants and 137 with placebo) showed no statistically significant difference between antidepressants and placebo (RR = 1.01, 95% CI 0.83–1.25) (Fig. 4). This corresponds to a relative risk increase of 1.0% (from a relative risk reduction of 17% in favour of antidepressants to a relative risk increase of 25%). The absolute risk increase is 0.6%, with a 95% CI ranging from an absolute risk reduction of 9.6% to an absolute risk increase of 14.1% (see online Appendix 4 for details). There was no statistically significant between-study heterogeneity. Including in the response analysis the two studies with dichotomous data imputed from continuous scores, data extracted from six studies (234 patients treated with antidepressants and 234 with placebo) showed no statistically significant difference between antidepressants and placebo (RR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.81–1.08) (Fig. 5). This corresponds to a relative risk reduction of 5.9% (from a relative risk reduction of 19% in favour of antidepressants to a relative risk increase of 8%). The absolute risk reduction is 3.7%, with a 95% CI ranging from an absolute risk reduction of 11.9% to an absolute risk increase of 5.0% (see online Appendix DS3 for details).

Fig. 1 Flow of information through the different study phases according to the Preferred Reporting Items for System reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA). Reference Judd, Rapaport, Yonkers, Rush, Frank and Thase38

Fig. 2 Review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Fig. 3 Random effects meta-analysis of the effect of antidepressants v. placebo on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores.

This analysis considered only the three studies that reported continuous outcome data.

Fig. 4 Random effects meta-analysis of the effect of antidepressants v. placebo on the proportion of patients failing to show an improvement.

This analysis considered only the four studies that reported dichotomous outcome data.

Fig. 5 Random effects meta-analysis of the effect of antidepressants v. placebo on the proportion of patients failing to show an improvement.

This analysis considered all six studies, including two studies with dichotomous data imputed from continuous scores.

No data were available in terms of proportion of patients with major depressive disorder at follow-up, as established with help of a standardised diagnostic interview. In terms of proportion of patients leaving the study early, data extracted from two studies (93 patients treated with antidepressants and 93 with placebo) showed no statistically significant difference between antidepressants and placebo (RR = 1.06, 95% CI 0.65–1.73) (online Appendix DS4). There was no statistically significant between-study heterogeneity.

Discussion

The present systematic review found evidence suggesting that there is unlikely to be a clinically important difference between antidepressants and placebo in patients with minor depression.

Although only six studies and fewer than 500 patients were included, we note that confidence intervals of treatment estimates were not very wide. For continuous scores, no research evidence or consensus is available about what constitutes a clinically meaningful difference in HRSD scores; Reference Moncrieff and Kirsch46 however, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence required a difference of at least three points as the criterion for clinical importance. 47 Although we recognise that this criterion is rather arbitrary, the lower confidence interval calculated in the present review, a mean difference of – 2.27 points in HRSD scores, does not cross this threshold. Similarly, for dichotomous outcomes the GRADE working group suggested a relative risk reduction of 25% as the threshold for clinical significance, and in our analysis the lower confidence interval of the relative risk reduction was 19%. We therefore conclude that there is evidence showing that there is unlikely to be a clinically important advantage for antidepressants in individuals with minor depression.

The clinically relevant depressive symptoms in minor depression may be considered on a continuum between no symptoms at one end and severe major depression at the other. Reference Kroenke48 This conceptualisation would imply that there are no qualitative differences between major depression and minor depression, but this has been questioned. Reference Geiselmann and Bauer49 Our results may reinforce the concept of a continuum as in individuals with major depression re-analysis of clinical trial data showed that the drug–placebo difference increases as a function of initial severity, rising from virtually no difference in mild depression to a relatively small difference for adults with moderate depression and a medium difference in severe depression. Reference Kirsch, Deacon, Huedo-Medina, Scoboria, Moore and Johnson50,Reference Fournier, DeRubeis, Hollon, Dimidjian, Amsterdam and Shelton51

Limitations

The limitations of the present analysis are those of the included primary studies. Three trials included fewer than 50 patients, and all six studies had short-term follow-up. Incomplete data reporting was a major issue: the proportion of patients who developed major depression at follow-up was never reported, mean values at study end-point were reported without the standard deviations in two studies, and two studies did not report the proportion of improved patients. Even more important, of the four studies that included patients with minor depression and major depression or dysthymia (online Table DS1), only in two was the randomisation stratified by diagnostic subtype.

Clinical implications

Despite these limitations, clinical and policy implications may be drawn. There is now a clear indication that psychological treatments for minor depression have a significant effect on depressive symptoms, at least in the short-term. Reference Cuijpers, Smit and van52 This indication, together with the results of the present systematic review, may suggest that antidepressants should not be considered for the initial treatment of individuals with minor depression. For benzodiazepines, although previous reports yielded contrasting results, Reference Birkenhager, Moleman and Nolen21,53 no studies were included in our review and so it is not possible to determine their potential therapeutic role in minor depression. We note that in clinical practice benzodiazepines are frequently prescribed for the treatment of patients with depressive symptoms; Reference Johnson54 however, the risk of drug misuse, dependence and withdrawal symptoms might outweigh any potential benefits related to their rapid anxiolytic effect.

Considering the extensive use of drugs for emotional complaints in absence of a diagnosis of major depression, Reference Demyttenaere, Bonnewyn, Bruffaerts, De Girolamo, Gasquet, Kovess and Haro14 shifting from drugs to psychological interventions would require investment in human resources, training and supervision, as well as additional time for healthcare providers to deliver the interventions. In systems with no or low resources doctors should still shift away from drug intervention as resources may be better spent elsewhere in the health system. There is clearly a need to develop alternative approaches to extend and scale up care to persons with this condition. 55

Funding

This systematic review was financially supported by the Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva, Switzerland. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors solely and do not necessarily represent the views, policies and decisions of WHO. C.B. and A.C. are grateful to the Fondazione Cariverona, who provided a three-year grant to the WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health and Service Organization at the University of Verona, directed by Professor Michele Tansella. V.P. is supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Glynn Lindsay, who performed the literature searches for this review.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.