Postnatal depression (PND) is characterised by both psychological and behavioural changes including fatigue, irritability, disturbance of appetite, insomnia and anhedonia, with 25% of women affected experiencing symptoms lasting over a year.Reference Morrell, Warner, Slade, Dixon, Walters and Paley1 There are several treatment models available to women with symptoms of PND, including psychotherapy and antidepressants, but there are challenges associated with each.Reference Morrell, Warner, Slade, Dixon, Walters and Paley1 Consequently, there is a need to identify further ways of supporting the mental health of new mothers. Given that studies examining predictors of PND have identified psychosocial factors such as daily hassles, parenting stress, chronic strain and both perceived and received social support,Reference Yim, Stapleton, Guardino, Hahn-Holbrook and Schetter2 group interventions that simultaneously relax mothers and enhance their support networks could be of value. In particular, there is theoretical research suggesting that singing could support new mothers: singing is widely practised in cultures around the world, with anthropological theories that singing even evolved with the aim of reassuring infants, promoting mother–infant bonding and supporting infant neurological development.Reference Falk3 Further, there have been a number of studies in different populations showing the benefits of singing for mental health in older adults,Reference Coulton, Clift, Skingley and Rodriguez4, Reference Cohen5 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseReference Lord, Hume, Kelly, Cave, Silver and Waldman6 and people with dementia.Reference Särkämö, Tervaniemi, Laitinen, Numminen, Kurki and Johnson7 Yet to date, there have been no controlled studies exploring the effect of singing on mental health in new mothers; specifically on symptoms of PND. Therefore, this three-arm parallel-group randomised controlled trial explored the impact of a 10-week community singing programme for mothers experiencing symptoms of PND and their babies compared with a comparison group undertaking a 10-week programme of community play activities and a control non-intervention group (trial registration: NCT02526407).

Method

Participants were adult women with babies up to 40 weeks post-birth who displayed symptoms of PND, indicated with a score of ≥ 10 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; a 10-item self-report measure scored from 0 to 30 with ≥ 10 indicative of possible depression and higher scores indicating more severe depression).Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky8 They were randomised using SPSS with a 1:1:1 allocation using random block sizes of six, stratified by age of their child and the severity of their EPDS score. Women were recruited through midwives, doctors, perinatal psychiatrists, health visitors and general practitioners in the Greater London area, as well as through social media, leaflets and by a research assistant in children's centres and in the local community. The study received ethical approval from the National Health Service Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 15/SS/0160) and all participants provided informed consent.

A total of 307 women were screened for participation, of whom 148 were eligible to participate and consented to take part, and 135 completed data collection (see supplementary Fig. 1, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2017.29). One participant reported not responding to the questions accurately so was retrospectively excluded, providing a final n of 134 (91% completion rate). There were no differences across any of the baseline variables measured between those who did complete and those who did not complete data collection. Participants were recruited and participated between December 2015 and August 2016. In the singing group, the median number of sessions attended was eight (mean 7.2, s.d. = 2.6) and in the play group, the median number of sessions attended was six (mean 5.7, s.d. = 2.8).

Participants randomised to the singing (experimental) and creative play (comparison) groups received weekly free 60 min workshops in groups of 8–12 for them and their baby for 10 weeks in a children's centre local to them (five groups ran per arm to accommodate all participants). Groups were led by professional workshops leaders, with the same leaders leading both the singing and creative play sessions to ensure consistency of person and place between the two conditions. Singing workshops involved mothers listening to songs sung by the leader, learning and singing songs with their babies, and creating new songs together reflecting aspects of motherhood. Creative play workshops involved mothers engaging in sensory play with their babies, doing arts and crafts and playing simple games together. Participants randomised to the control group did not receive any workshops above and beyond their usual care for 10 weeks but were provided with singing classes at the end of their research participation as a thank you. No adverse events were reported across the study.

Participants provided baseline demographic data and completed the EPDS at baseline, week 6 and week 10. Data were analysed using IBM SPSS version 23.0. Baseline comparisons using one-way ANOVAs, Kruskal–Wallis test and Chi-square test for linear, ordinal and categorical data respectively revealed that groups were well matched (supplementary Table 1). Changes across time were measured using two-way repeated measures ANOVAs looking at the effects across time and the time × group interaction. Given that there are two recommended levels of EPDS cut-off (EPDS ≥ 10 for symptoms of PND and EPDS ≥ 13 indicating more severe depression; sometimes classed as minor and major PND),Reference Gibson, McKenzie-McHarg, Shakespeare, Price and Gray9 planned sensitivity analyses were performed parallel to the main analyses using EPDS ≥ 13.

Results

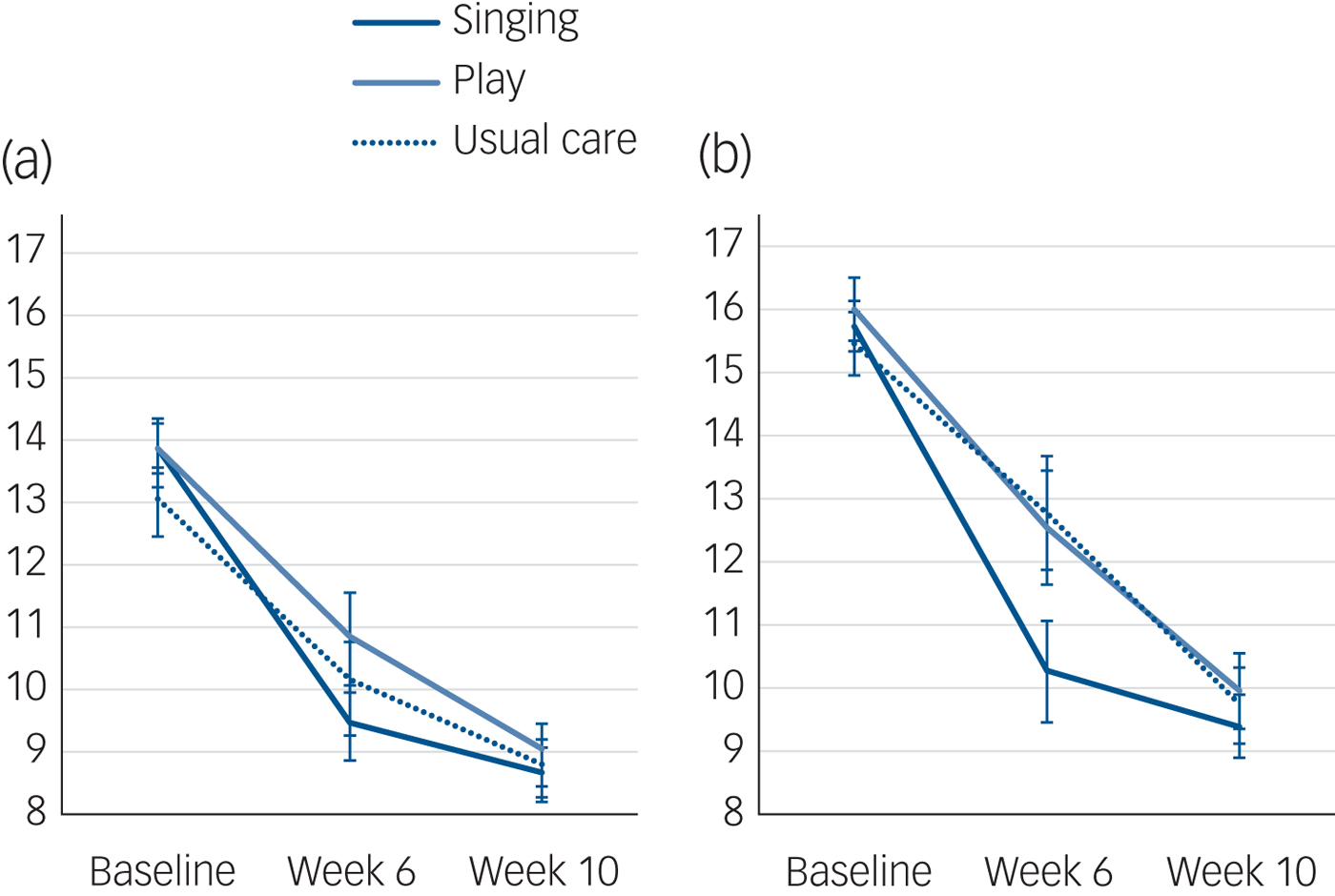

There was a significant decrease across time in EPDS score, indicating that women in all three groups experienced improvements in symptoms of PND across the 10 weeks (EPDS ≥ 10: F 2,262 = 143.21, P < 0.001, η 2 = 0.52; EPDS ≥ 13: F 1.9,139.8 = 118.39, P < 0.001, η 2 = 0.60). When considering the time × group interaction, using EPDS ≥ 10, there was no significant effect (F 4,262 = 1.66, P = 0.16, η 2 = 0.012). However, using EPDS ≥ 13, the time × group interaction reached significance (F 3.9,139.8 = 2.74, P = 0.033, η 2 = 0.028). To explore over which time period this time × group difference occurred, we looked at the within-participant contrasts, which showed a significant difference between groups from baseline to week 6 (EPDS: F 2,72 = 3.93, P = 0.024, η 2 = 0.05), but showed the difference between groups narrowing again by week 10 (F 2,72 = 0.27, P = 0.76, η 2 = 0.001) (Fig. 1). To explore which group differed across this period of significance, we ran ANOVAs of the change from baseline to week 6, which confirmed the significant difference between groups (F 2,72 = 3.93, P = 0.024, η 2 = 0.10), with post hoc tests with Bonferroni corrections demonstrating that the singing group had a significantly faster improvement than the control group (mean difference −2.83, s.e. = 1.06, 95% CI −5.44 to −0.22, P = 0.029, d = 0.78) but not the play group (mean difference −2.03, s.e. = 1.05, 95% CI −4.61 to 0.54, P = 0.17, d = 0.56), with no difference between the play and control group (mean difference −0.80, s.e. = 1.13, 95% CI −3.57 to 1.97, P > 0.99, d = 0.20). Descriptive statistics are provided in supplementary Table 2, and show that this improvement among the singing group equated to an average 35% decrease in depressive symptoms across the first 6 weeks by which point 65% of the singing group no longer had an EPDS ≥ 13. This decrease in depressive symptoms in the singing group extended to a 40% decrease by week 10, by which point 73% of the singing group no longer had an EPDS ≥ 13. Sensitivity analyses factoring as covariates whether mothers were also receiving additional support for their mental health alongside involvement in the study did not affect the significance of ANOVA results either across time or for the time × group interaction.

Fig. 1 Changes in depression from baseline to week 10. (a) Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) ≥ 10 and (b) EPDS ≥ 13 with standard error in singing, play and usual care groups.

Discussion

This study supports findings from previous studies showing that symptoms of PND improve over time.Reference Cooper, Campbell, Day, Kennerley and Bond10 However, mothers involved in the singing group had a significantly faster decrease in their symptoms. Research suggests that children whose mothers experienced PND have higher rates of insecure attachments and poor emotional adjustment in the early years, delays in reading and demonstration of behaviour disturbances and impaired patterns of communication 5 years on.Reference Cooper and Murray11, Reference Harris, Huckle, Thomas, Johns and Fung12 However, early remission from PND has been associated with reduced effects on both mother and baby.Reference Harris, Huckle, Thomas, Johns and Fung12 Consequently, evidence that singing interventions could speed the rate of recovery in women affected by symptoms of PND could have clinical relevance.

It is notable that there was no significant difference in speed of recovery between the play group and controls. This might suggest that the social support provided by the play group was not enough in itself to improve symptoms of PND and that there were characteristics specific to the singing group that played a key role in the improvements found. However, it is noted that post hoc tests showed the singing group did not have a significantly faster improvement than the play group, implying that the social support provided by the play group was, if not an entirely explanatory factor, at least a factor in the improvements found in the singing group.

Regarding limitations, participants and researchers were not masked to the groups they were allocated to. However, women were not informed that the study hypothesis involved singing having significantly different results to the play group, so the fact that there were no improvements in the play group compared with the control would seem to suggest results were not entirely driven by placebo. Overall, this study suggests that 10-week programmes of group singing workshops could help speed the recovery from symptoms of PND among new mothers. Although the study sample size is in line with previous studies exploring the effects of interventions for the treatment of PND,Reference Bledsoe and Grote13 further work needs to be undertaken to replicate the findings with a larger sample size and to ascertain the viability of such workshops in clinical practice.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2017.29.

Funding

The study was funded by Arts Council England Research Grants Fund, grant number 29230014 (Lottery) with additional support from CW+ and Dasha Shenkman.

Acknowledgements

The study team acknowledge the support of the National Institute of Health Research Clinical Research Network (NIHR CRN). The authors would like to thank the hospitals involved as participant identification centres as well as Diana Roberts, Miss Sunita Sharma, Professor Aaron Williamon and Sarah Yorke for their support with the study.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.