Psychiatry is inconceivable without clinician questions. They are the mechanism for achieving clinical objectives: history taking, reviewing symptoms and deducing diagnostic hypotheses. Questioning also manages the formation of a therapeutic alliance, the benefits of which include concordant treatment decisions and patient adherence. Reference Thompson and McCabe1 Developing evidence-based interviewing techniques to improve these outcomes is crucial, particularly in the case of schizophrenia where psychotic symptoms may problematise interaction. Reference McCabe, Heath, Burns and Priebe2 A conceptual issue hinders this in practice – there is no definitive model of ‘good’ communication. Reference Priebe, Dimic, Wildgrube, Jankovic, Cushing and McCabe3 Instead, it is viewed more generically through the ideology of ‘patient-centredness’, i.e. accounting for the patient's psychosocial context, preference and experience. Although questions are the mode of eliciting this experience, advice in psychiatry textbooks is often limited and generalised, e.g. ‘in general try to use open questions rather than leading questions or closed questions’. Reference Burton4 In practice, ‘open’ and ‘closed’ categories encompass numerous linguistic question types, each of which may have different interactional consequences. Reference Heritage, Freed and Ehrlich5 No research to date has examined the actual questions – by means of a sensitive, utilitarian classification – that psychiatrists deploy in clinical encounters and how they are linked to the therapeutic alliance and treatment adherence. To specify training and improve these outcomes, we must first explore two research questions, the aims of this study: first, what types of questions do psychiatrists ask patients in routine consultations, and second, do particular question types predict better therapeutic alliances and treatment adherence?

Method

Data were drawn from a UK Medical Research Council study examining clinical interaction in psychosis, Reference McCabe, Healey, Priebe, Bremner, Lavelle and Dodwell6 collected between 2006 and 2008. Thirty-six psychiatrists from out-patient and assertive outreach clinics across three centres in England (one urban, one semi-urban and one rural) were randomly selected, of whom 31 consented to participate (86%). Their patients meeting DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were also invited to participate. 7 Of 579 eligible consecutive attenders, 188 persons did not attend their appointment, 42 were not approached for clinical reasons (deemed too unwell) or logistical reasons (overlapping appointments) and 211 declined to take part. Written informed consent was obtained from 138 (40%) of those invited, following which their consultations were audiovisually recorded. Four encounters were excluded owing to inadequate recording quality. Verbal dialogue was transcribed verbatim; the final set of 134 transcripts formed our data-set.

Question coding

A standardised protocol (online Fig. DS1) was developed and piloted collaboratively by a team with experience in linguistics (C.H.) and psychiatric communication (L.T. and R.M.). Regular meetings facilitated the refinement of the protocol, applied by all team members to transcripts of video-recorded consultations in an iterative piloting process. The resulting coding scheme allowed an exhaustive classification of questions within each transcript. Question taxonomies that move beyond an ‘open’ v. ‘closed’ conceptualisation vary according to the accepted meaning of the question itself: broadly, syntactically (by form), semantically (by meaning) or pragmatically (by function). Reference Groenendijk, Stokhof, van Benthem and ter Meulen8 Based on examination of the transcripts, our approach used a combination of these classifications to identify and distinguish all items of interest. Where possible, questions were identified by their syntactic form. However, although there are two types of sentence forms that constitute syntactic questions in English – starting the sentence with a ‘wh-’ word, and swapping the order of the sentence's subject and auxiliary verb (subject–auxiliary inversion), Reference Ginzburg and Sag9 these are by no means the only ways that questions may be asked. For example, specific lexical items may be commonly used as and taken to be questions (e.g. ‘Pardon?’), Reference Drew10 and sentences that are syntactically identical in form to non-interrogatives may be used and identified as questions by theirrising (questioning) intonation.The classification sought to identify all of these question types.

Question categories

The complete coding protocol was constructed to be usable without specific knowledge of linguistics. Each candidate utterance was tested against a hierarchy of yes/no format questions, formulated to be as simple as possible (Fig. DS1). A process of sequential elimination thereby identifies the linguistic type of any question, and this process is repeated on the utterance until no further questions are identified. There are ten possible categories:

-

(a) Yes/no questions: ‘Do you ever feel someone is controlling your mind?’

-

(b) ‘Wh-’ questions: ‘Where was that done?’

-

(c) Declarative questions: ‘So you feel a bit anxious?’

-

(d) Tag questions: ‘You're on 10 mg of olanzapine, aren't you?’

-

(e) Lexical tags: ‘I'll write a letter to your GP, okay?’

-

(f) Incomplete questions: ‘Your keyworker is?’

-

(g) Alternative questions: ‘Do you feel better having stopped it, or worse?’

-

(h) Check questions: ‘Yeah?’

-

(i) ‘Wh-’ in situ: ‘He did what?’

-

(j) Open class repair initiators: ‘Pardon?’

Yes/no questions

Yes/no questions are one of the class of ‘closed’ questions because their expected answer is ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Reference Heritage and Clayman11 They are syntactically identifiable with an auxiliary verb in the first position of the sentence, followed by the subject. Auxiliary verbs often express distinctions of tense, aspect or mood and include the verbs do, can, will, have, did: ‘Did you really believe it at the time?’, ‘Have you asked your GP about that?’, ‘Will you think about reducing your depot?’

‘Wh-’ questions

‘Wh-’ questions have a question word in the first position: who, what, when, why or how. Accordingly, they elicit information on a state of affairs or the property of an event. ‘Wh-’ questions are considered to be open questions because they do not project a specific response: ‘How does that make you feel?’, ‘What do you mean?’, ‘Who is your keyworker?’

Declarative questions

Declarative questions have the syntax of a declarative sentence. Reference Heritage and Clayman11 A rising intonational contour is likely to index recognition of declaratives as questions, Reference Stivers and Rossano12,Reference Safarova and Swerts13 i.e. requiring (dis)confirmation from the patient. Questioning intonation was annotated in the transcripts, so we included all declarative sentences followed by a question mark. Coders also looked to the next turn (the patient response) to see whether the sentence had indeed been understood as a question. Declarative questions are considered to be ‘closed’ questions, Reference Raymond, Freed and Ehrlich14 because they invite yes/no type responses: ‘You feel happy about that?’, ‘You're still on the same medication?’, ‘Sleeping okay?’

Tag questions

A tag question transforms a declarative statement or imperative into a question by adding an interrogative fragment (the tag), i.e. an auxiliary verb followed by a pronoun: isn't it, would he, do you. Like yes/no questions and declaratives, tag questions can be seen as inviting confirmation or disconfirmation from the patient, thus are another class of ‘closed’ question: ‘You're on 20 mg now, aren't you?’, ‘You were thinking about working in old people's homes, weren't you?’

Lexical tags

Lexical tags also invite confirmation or disconfirmation by adding an interrogative fragment to a statement. A list of words that could act as lexical tags, such as right, okay, yeah, you know, was provided to coders. Lexical tags transcribed with a question mark were included, for example: ‘We can increase the dose, okay?’, ‘Sometimes it can take a bit of adjusting to, you know?’

Incomplete questions

Grammatically incomplete sentences that invited a candidate completion by the patient were coded as incomplete questions. They may be initially formulated as another syntactic structure, e.g. a declarative or alternative question, but invite – through questioning intonation – the patient to complete the missing component: ‘You've got a job, or?’, ‘You take that at night, or?’

Alternative questions

Like yes/no questions, alternative questions have an auxiliary verb in the first position, but present two or more possible answers that the patient may choose, e.g. ‘Do you prefer morning or afternoon?’, ‘Are you taking that regularly or just when you need it?’

Check questions

Check questions are synonymous in form with lexical tags, but follow a statement by the patient:

Patient: ‘I'd be happy with that.’

Doctor: ‘Yeah?’

‘Wh-’ in situ

‘Wh-’ in situ questions are formed using ‘wh-’ words, but as a replacement for content words instead of at the beginning of the sentence:

‘John went to the zoo’

‘John went where?’ (cf. Where did John go?)

Examples are: ‘You did that when? ‘He said what?’

Open class repair initiators

Psychiatrists may draw attention to a problem of hearing or understanding the patient's prior turn using questions that are open class repair initiators, i.e. they ‘flag’ trouble with the patient's prior turn of talk, but leave open the nature of the problem: Reference Drew10 examples are ‘Pardon?’, ‘Sorry?’, ‘What?’, ‘Huh?’

Application of the protocol

A software suite designed for the annotation of language data, Dexter Coder, was used to apply the protocol. Reference Coder15 Four raters performed the coding independently. Transcripts consisted of verbal dialogue, therefore assigned question codes were based only on surface syntax, intonational cues and patient responses. Interrater reliability was found to be good for all question types using Cohen's kappa, which ranged from 0.76 to 0.89.

Measures and outcomes

Symptoms were assessed immediately post-consultation, and psychiatrists rated their view of the therapeutic relationship for each patient. Patient treatment adherence was assessed by psychiatrists in a follow-up interview, 6 months after the consultation.

Symptoms

Symptoms were assessed as a potential confounding factor in interviews by researchers not involved in the patient's treatment. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) was employed in which 30 items rated 1–7 assess positive, negative and general symptoms, with higher scores denoting greater severity. Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler16 Positive symptoms indicate a change in the patient's behaviour or thoughts, e.g. delusions or sensory hallucinations. Negative symptoms represent a reduction in functioning, including blunted affect, emotional withdrawal and alogia. Subscale scores for positive and negative symptoms range from 7 (absent) to 49 (extreme); scores for general symptoms such as anxiety range from 16 (absent) to 112 (extreme). Interrater reliability using audiovisually recorded interviews was good (Cohen's κ = 0.75).

Therapeutic alliance

Psychiatrist perceptions of the therapeutic alliance were assessed post-consultation using the Helping Alliance Scale. Reference Priebe and Gruyters17 Five items were rated 1–10 on various interpersonal variables including mutual understanding about providing necessary treatment and rapport with the patient. Ratings for individual items were combined to create a single value. A lower score represented a poorer therapeutic relationship.

Adherence to treatment

Mean percentage adherence, grouped in clusters as recommended by Velligan et al, Reference Velligan, Lam, Glahn, Barrett, Maples and Ereshefsky18 was assessed 6 months after the consultation by the patient's psychiatrist. Psychiatrists used collateral information to assess adherence in 50% of cases. In 56% of these cases this was attendance for depot injection, supervised drug intake or blood tests. In 44% this was from others involved in the patient's care (e.g. pharmacist, general practitioner, family member).

Adherence to treatment in general (i.e. the percentage of occasions that scheduled appointments were kept and non-medication recommendations were followed) and adherence to medication (i.e. the percentage of medication taken) were rated separately on a three-point scale: >75% (rated 1), 25–75% (rated 2) and <25% (rated 3). Reference Buchanan19 The two scores were summed to yield a total adherence score ranging from 2 to 6, with a lower score indicating better adherence.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 18.0. 20 Descriptive data, including frequencies and means, on question types were retrieved to address our first research question. To explore our second research question, bivariate correlations between each question type and the primary outcomes were performed, establishing significant associations to motivate further analysis. Initially, correlations with symptoms, a potential confounder, were explored. Coefficients were then obtained for adherence and the therapeutic alliance. The associations between question types (the independent predictors) and the primary outcomes (the dependent variables: adherence, the therapeutic alliance) were further assessed using generalised estimating equations (GEE). A GEE analysis was used to account for within-individual correlations. Reference Liang and Zeger21,Reference Ballinger22 The unit of analysis was the consultation. As each psychiatrist was involved in consultations with several patients, psychiatrist identity was entered as a within-individual factor; this militates against the possibility that personal interviewing style might exert a disproportionate effect on the results. In addition, as the correlations showed that symptoms and question types were not independent, the three symptom scales were also entered as within-individual factors.

Results

Questions were coded in 134 consultations involving 30 psychiatrists; of these clinicians, 63% were men and 72% were of White ethnic origin. Consultations lasted a mean length of 17.2 min (s.d. = 9.1). A total of 114 patients were recruited from out-patient clinics and 24 from assertive outreach clinics. Table 1 displays their sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Table 1 Patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

| Sociodemographic variables, n (%) a | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 87 (63) |

| Female | 47 (37) |

| Ethnicity, White | 100 (72) |

| Employment | |

| Unemployed | 86 (62) |

| Employed/student | 30 (22) |

| Voluntary | 10 (7) |

| Retired | 8 (6) |

| Clinical variables, mean (s.d.) | |

| Age, years | 42.2 (11.5) |

| Years in contact with psychiatric services | 15.6 (11.6) |

| Number of admissions | 3.4 (3.4) |

| Number of involuntary admissions | 1.8 (2.6) |

| Symptoms (PANSS score) | |

| Total score | 54.4 (18.6) |

| Positive | 13.1 (5.9) |

| Negative | 12.5 (5.8) |

| General | 28.8 (9.6) |

PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

a. Total sample n = 138, data analysed for n = 134.

Types of questions asked

Psychiatrists asked patients a total of 7570 questions across 134 consultations with a mean of 51.7 (s.d. = 32.1) questions per consultation. Table 2 lists the mean frequencies of the specific question types in descending order. As length and density of doctor utterances varied between consultations, means were also normalised by calculating values per 1000 words; this controlled for the possibility that higher question frequencies were due to some psychiatrists talking more. Most frequently psychiatrists asked patients yes/no questions (mean = 16.5), followed by ‘wh-’ questions (mean = 12.7), declarative questions (mean = 11.0) and tag questions (mean = 3.9). Given the relatively low raw frequency of the remaining linguistic types, only these four categories were sufficiently frequent to include in statistical analyses exploring associations with the therapeutic alliance and adherence.

Table 2 Distribution of question types

| Total | Mean (s.d.) | Range | Mean per 1000 words (s.d.) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All questions | 7570 | 51.7 (32.1) | 165 | 35.0 (16) | 93 |

| Yes/no questions | 2362 | 16.5 (12.2) | 57 | 12.0 (6) | 30 |

| ‘Wh-’ questions | 1700 | 12.7 (10.4) | 63 | 8.5 (4.8) | 23 |

| Declarative questions | 1648 | 11.0 (8.3) | 47 | 9.0 (8) | 40 |

| Tag questions | 842 | 3.9 (4.5) | 25 | 2.3 (2.1) | 11 |

| Lexical tags | 496 | 3.7 (5.2) | 29 | 2.0 (2.2) | 11 |

| Incomplete questions | 196 | 1.5 (1.7) | 8 | 1.1 (1.8) | 12 |

| Alternative questions | 159 | 1.2 (1.5) | 10 | 0.8 (1.2) | 9 |

| Check questions | 85 | 0.6 (1.4) | 7 | 0.4 (1.2) | 6 |

| ‘Wh-’ in situ | 47 | 0.4 (1) | 10 | 0.2 (0.6) | 5 |

| Open class repair initiators | 35 | 0.3 (0.7) | 4 | 0.2 (0.6) | 4 |

Correlations with outcomes

Bivariate associations between outcomes and the four most frequent question formats were examined using Spearman correlations. Correlation coefficients and values of significance for each measure are reported below. Statistically significant findings (at the P<0.05 level) are described.

Symptoms

Because symptom severity in schizophrenia can affect communication, we explored correlations between each question type and the three PANSS subscales (positive, negative, general). Yes/no questions were positively correlated with negative symptoms and ‘wh-’ questions were positively correlated with positive symptoms (Table 3). Declarative and tag questions were not associated with any symptom subtype.

Table 3 Correlation of outcomes with the four question types

| Question type | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes/no | ‘Wh-’ | Declarative | Tag | |||||

| r | P | r | P | r | P | r | P | |

| Symptoms | ||||||||

| General | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.82 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| PANSS positive | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.18* | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.75 | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| PANSS negative | 0.18* | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.93 | −0.01 | 0.91 | −0.03 | 0.76 |

| Therapeutic alliance (HAS score) | 0.03 | 0.73 | 0.10 | 0.26 | 0.28** | <0.01 | 0.04 | 0.68 |

| Adherence | 0.04 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.72 | −0.20* | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

HAS, Helping Alliance Scale; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

* P<0.05,

** P<0.01.

Therapeutic alliance

Correlations between the therapeutic alliance as measured by Helping Alliance Scale scores and question type are shown in Table 3. Only declarative questions were associated with better clinician perceptions of the therapeutic alliance (P<0.001).

Adherence

Only psychiatrists' use of declarative questions was negatively correlated with the adherence scale (Table 3), i.e. greater use of declarative questions from the psychiatrist was associated with higher patient adherence at follow-up (P<0.05).

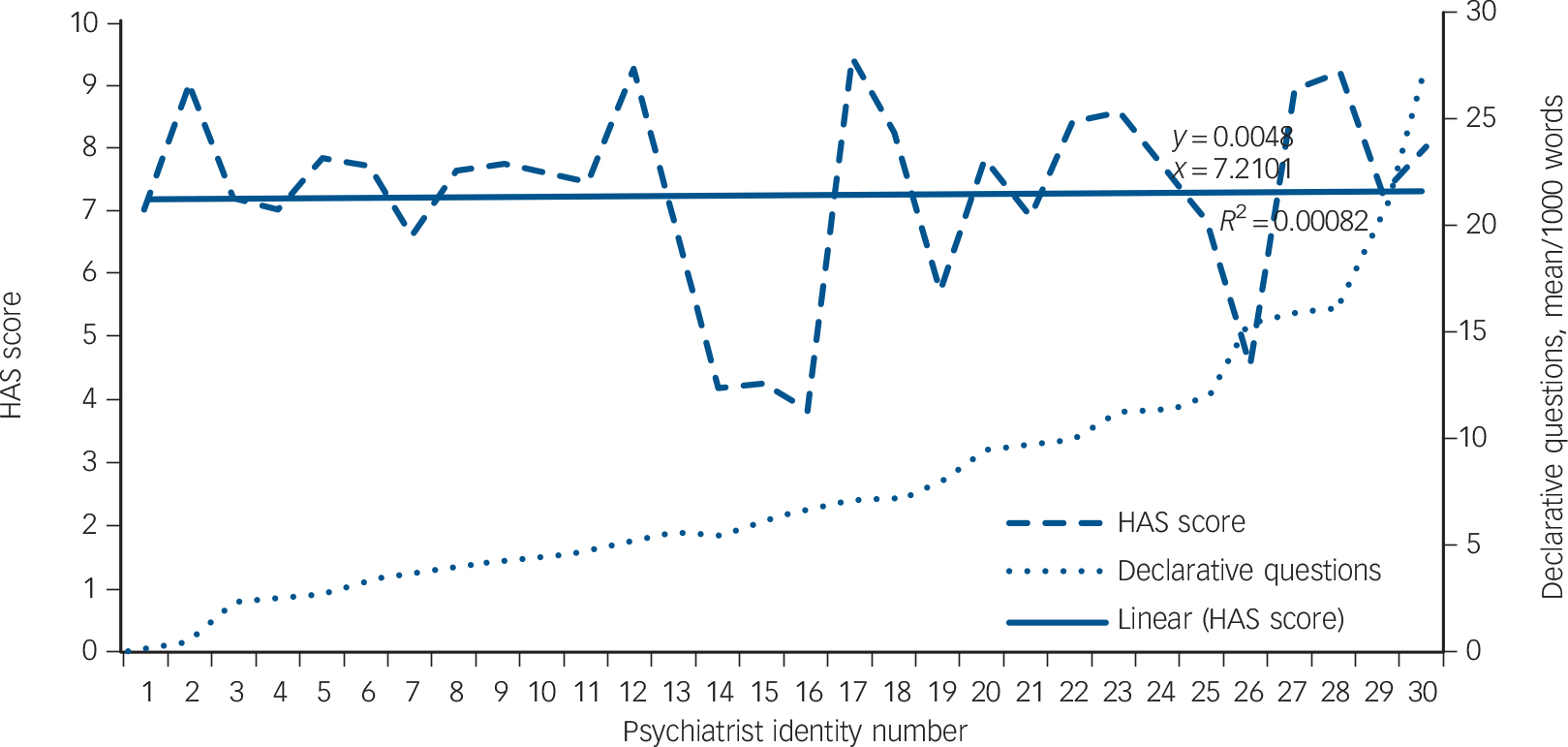

Between-psychiatrist variation

Given the significant correlations with both therapeutic alliance and adherence, we examined individual variation in psychiatrists' use of declarative questions to consider how clinician identity may influence these outcomes. The number of consultations and mean number of declarative questions, normalised per 1000 words, for each psychiatrist are listed in online Table DS1, as well as the range (the minimum and maximum number of declarative questions). There was great variation in the number of declaratives used, with means varying from 0 to 28 per 1000 words, even within psychiatrists' own consultations – one psychiatrist recorded a range of 6–32 within four consultations. Moreover, plotting the mean declaratives per 1000 words against adherence (Fig. 1) and therapeutic alliance (Fig. 2) for each psychiatrist showed no apparent clustering effect. However, given that psychiatrists were often involved in a number of patient consultations (a mean of 4.6 per clinician), separate GEE models were fitted to these two outcome variables to account for the potential effect of psychiatrist identity on the data.

Fig. 1 Adherence and use of declarative questions.

Fig. 2 Therapeutic alliance and use of declarative questions. HAS, Helping Alliance Scale.

Generalised estimating equations

Each GEE used a gamma distribution with a log link function, and controlled for within-individual correlations of psychiatrist and the three symptom scales using an independent correlation matrix. The independent variables in each case were the proportion of each of the four question types normalised per 1000 words.

Therapeutic alliance

Even after adjusting for psychiatrist identity and patient symptoms there was a significant main effect on psychiatrists' ratings of the therapeutic alliance in terms of the amount of ‘wh-’ questions and declarative questions that the psychiatrist used, adjusted for the amount of speech (Table 4). However, these effects were in opposite directions: psychiatrists rated the therapeutic alliance as better if they used more declarative questions, and worse if they used more ‘wh-’ questions.

Table 4 Generalised estimating equation results for therapeutic alliance and patient adherence

| B | SE | 95% CI | Wald χ2 | d.f. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAS total score a | ||||||

| (Intercept) | 1.97 | 0.05 | 1.86 to 2.07 | 1363.58 | 1 | <0.001 |

| ‘Wh-’ questions | −13.74 | 5.41 | −24.34 to −3.13 | 6.44 | 1 | 0.011 |

| Tag questions | 12.74 | 9.11 | −5.13 to 30.60 | 1.95 | 1 | 0.162 |

| Yes/no questions | 0.77 | 3.45 | −6.00 to 7.54 | 0.05 | 1 | 0.824 |

| Declarative questions | 11.60 | 2.27 | 7.15 to 16.04 | 26.14 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Adherence total score b | ||||||

| (Intercept) | 0.95 | 0.09 | 0.77 to 1.13 | 107.90 | 1 | <0.001 |

| ‘Wh-’ questions | 13.36 | 8.52 | −3.34 to 30.05 | 2.46 | 1 | 0.117 |

| Tag questions | 4.82 | 18.33 | −31.12 to 40.75 | 0.07 | 1 | 0.793 |

| Yes/no questions | 3.66 | 6.21 | −8.50 to 15.83 | 0.35 | 1 | 0.555 |

| Declarative questions | −16.40 | 3.43 | −23.12 to −9.68 | 22.89 | 1 | <0.001 |

HAS, Helping Alliance Scale; SE, standard error.

a. Goodness of fit: quasi-likelihood under independence model criterion (QIC) = 15.40; QIC corrected (QICC) = 19.38.

b. Goodness of fit: QIC=26.67, QICC=26.33.

Adherence

There was a main effect of declarative questions on adherence, even when controlling for patients' symptoms and the identity of the psychiatrist (Table 4). This suggests that if psychiatrists used more declarative questions in their consultations, patients would be more likely to adhere to their treatment, as measured 6 months after the consultation.

Declarative questions in practice

Declarative questions were the only question subtype associated with better clinician-rated adherence and therapeutic relationships. This raises the question of what kinds of activity they are performing in practice. On examination of 210 declaratives extracted from a random subset of 30 consultations (with mean frequencies above 3 per 1000 to ensure selected cases contained a sufficient density of questions) three distinctions were immediately observable. A minority appeared in a ‘checklist’ form (16; 8%) – truncated questions that may represent rapid topic shifts following a patient answer to a prior question, Reference Heritage, Freed and Ehrlich5 e.g. ‘Sleeping okay?’, ‘Good appetite?’ A slightly larger proportion (23; 11%) incorporated patients' immediately prior talk, repeating lexical elements verbatim, Reference Robinson and Kevoe-Feldman23 for example:

Patient: ‘I've had some side-effects.’

Doctor: ‘You've had some side-effects?’

The majority of questions, however, displayed a further level of abstraction – conveying ‘inferences or assumptions’ about the patients' prior talk (171; 81%). Reference Heritage, Freed and Ehrlich5 Over half of these were a homogeneous subgroup of ‘so-prefaced’ inferences (90; 53%) such as, ‘So you feel a bit anxious?’ (20 specific examples of these questions are given in the Appendix). Each declarative is prefaced by the upshot marker ‘so’, Reference Schiffrin24 following which the psychiatrist invites confirmation of an emotional inference. ‘So’ indexes inferential or causal connections with the prior talk Reference Bolden25 and displays the psychiatrist working closely with the patient's contribution. In each example the clinician produces a display of understanding, ‘formulating’ the patient's feelings or perspective, e.g. being ‘anxious’, ‘happy’, ‘lethargic’, ‘depressed’ or ‘under pressure’. Garfinkel & Sacks Reference Garfinkel, Sacks, McKinney and Tiryakian26 first identified the use of such formulations in interaction:

‘a member may treat some part of the conversation as an occasion to describe that conversation, to explain it, or characterise it or explicate, or translate, or summarise or furnish the gist of it … that is to say, a member may use some part of the conversation as an occasion to formulate the conversation’. Reference Garfinkel, Sacks, McKinney and Tiryakian26

The formulations in the Appendix characterise the personal salience of the conversation for the patient. The following data fragment shows a ‘so-prefaced’ declarative question in context: here the psychiatrist edits the patient's talk to highlight its psychological implications:

Patient: It's just that sometimes in the afternoon I get like, you know, I get the feeling that it's going to happen to me, I will end up in the hospital.

Doctor: Okay.

Patient: And, er,

Doctor: So you feel a bit anxious?

Patient: Yeah.

Here the psychiatrist uses a declarative question to distil the central theme of a larger stretch of talk concerning the patient's fears about relapse and associated return to an in-patient ward. He proposes – and invites confirmation of – a candidate understanding within an emotional frame of relevance, inferring that the patient's ‘feeling that it's going to happen to me’ means he is feeling ‘anxious’. A similar extract is given below:

Patient: Yeah, I like to chill out in the house, Doctor, you know, I watch telly and then cook something and then washing and tidy the house up, you know?

Doctor: Yeah. So you're quite happy being on your own?

Patient: I'm quite happy, Doctor. Yeah, yeah.

The psychiatrist uses a declarative formulation to propose an understanding of the patient's stance in relation to how he spends his time alone at home. His deduction ‘you're quite happy being on your own’ is distilled from the patient's ‘I like to chill out in the house’. Such formulations have been studied extensively in psychotherapy as devices for suggesting ‘something implicitly meant by the client’, Reference Bercelli, Rossano, Viaro, Perakyla, Antaki, Vehvilainen and Leudar27 which display understanding, cooperation and engagement, yet simultaneously serve clinical objectives. Reference Antaki, Perakyla, Antaki, Vehvilainen and Leudar28 These intermittent ‘summaries’ are produced in service of therapeutic interpretation Reference Antaki, Perakyla, Antaki, Vehvilainen and Leudar28 and, in this context, consistent with a psychiatric point of view. Several implications for understanding psychiatric questioning and the direction of future research can be collectively extracted from these findings.

Discussion

Psychiatrists can use a range of methods to elicit information from patients by varying the structure of their questions. We captured these alternatives in a coding protocol, usable across a variety of medical contexts. There are three main findings from this study, each with applied significance. Despite the different possibilities of question form, psychiatrists used a relatively small subset frequently: yes/no questions (the prevalence of which is consistent with findings in general medicine), Reference Roter and Hall29 ‘wh-’ questions, declarative questions and tag questions. Although this pattern is of interest in its own right, choice between these question types may be consequential for clinical outcomes. Psychiatrists' use of declaratives – statements that invite patient (dis)confirmation (a subclass of ‘closed’ question) – predicted better psychiatrist perceptions of the therapeutic relationship and subsequent patient adherence at 6 months, after adjusting for symptoms, psychiatrist identity and amount of speech. Conversely, psychiatrist ‘wh-’ (open) questions, inviting more elaborate responses, correlated with more severe positive symptoms and predicted worse psychiatrist perceptions of the patient relationship. The findings counter commonly held assumptions regarding the conventional binary distinction between open (positive) and closed (negative) questions often used to construe a model of patient-centred care, e.g. using ‘open-ended questions to learn about the patient’. Reference Hanyok, Hellman, Rand and Zeigelstein30 Indeed, closer observation of the current data suggests that declarative questions can be deployed to display an understanding of patient experience.

Limitations

This study should be considered in the context of its limitations. Potential inferences regarding the direction of effect on adherence and the therapeutic relationship are constrained by the statistical methods used here: correlation cannot determine causality. Moreover, encounters included only patients diagnosed with schizophrenia; we cannot with any certainty extrapolate findings to other mental health populations that may have different communicative needs. The construct validity of the outcomes measured should also be considered. Although subjective measures of the therapeutic alliance are well accepted to assess the therapeutic relationship, they are more problematic, albeit heavily relied on, Reference Thompson and McCabe1 when assessing adherence. Provider ratings of adherence may be based on the report of the patient or on a worsening clinical condition, which may be related to failure of the chosen medication to control symptoms. Reference Velligan, Lam, Glahn, Barrett, Maples and Ereshefsky18 Moreover, doctors' ratings of adherence are frequently related to their perception of clinician–patient agreement. Reference Phillips, Leventhal and Leventhal31 This could go some way towards explaining why alliance and adherence were both associated with declarative questions. The study also does not allow for the fact that patients may have had contacts with other health professionals over the 6-month period. Although it is the psychiatrist with whom the patient makes treatment decisions, other individuals may also have some influence on adherence behaviour.

Our approach to question coding relied on pre-defined properties of a question's form, supporting reliable interrater coding. However, the categories were based predominantly on syntactic structure. This is problematic from some standpoints: what linguistically defines questions as questions does not necessarily define them as interactional objects – a question without the linguistic form of a question may still accomplish questioning, and the form of a question can be used for actions other than questioning. Reference Schegloff, Maxwell Atkinson and Heritage32 If there is no exact one-to-one correspondence between form and action, further explanatory potential may lie in contextual qualitative analyses of questions in situ. Our analysis focused on psychiatrists' questions. Previously, we found that the more questions patients asked to clarify the psychiatrist's talk, the more adherent to treatment they were 6 months later. Reference McCabe, Healey, Priebe, Bremner, Lavelle and Dodwell6 This raises the question of how psychiatrist questioning affects patient questioning, an avenue for further research.

Clinical implications

The findings suggest that a more sensitive classification than ‘closed’ v. ‘open’ is necessary to inform understanding of best questioning practices in psychiatry. Declaratives were the only class of closed question – from six possible subtypes – to be associated with better alliance and adherence. Although these are often labelled as negatively connotated ‘leading’ questions, Reference Burton4 this association (and actual data examples) suggests the function and consequences of declaratives may be more nuanced. Indeed, prior qualitative research of declarative questions in psychotherapy settings aligns with this. By displaying a more ‘knowing’ stance than other question types, Reference Heritage, Freed and Ehrlich5 declaratives create an opportunity for patients to confirm their psychiatrist's grasp of their state of affairs (e.g. ‘so you feel a bit anxious?’), such that they can function and be heard as displays of understanding, Reference Antaki, Perakyla, Antaki, Vehvilainen and Leudar28 empathy, Reference Ruusuvuori33 and active listening. Reference Hutchby34 Arguably, each of these may be be instrumental to the formation of therapeutic rapport and alliance.

Although the objectives and challenges of psychotherapy may be somewhat distinct from psychiatry, this prompts further qualitive research to understand the function of declaratives in psychiatry specifically. In the treatment of schizophrenia, the psychiatrist must balance information gathering with responsivity to patient experience, all the while maintaining an attitude of non-confrontation and non-collusion. Reference Turkington and Siddle35 When proposing how patients might ‘feel’ on account of their reports, declarative questions may allow clinicians to be sensitive to the emotional aspects of their experiences, while (where appropriate) sustaining a clinically desirable attitude of non-collusion with aspects of content, reconciling these sometimes diametrical requirements. Within the context of reviewing a patient's mental state, interviewing patients without using this kind of device may appear insensitive and be more characteristic of a stilted checklist approach to questioning. It is interesting that this psychotherapeutic practice is associated with better psychiatrist ratings of the therapeutic alliance. Importantly, clinician ratings of the therapeutic alliance have been found to predict outcomes in psychosis, Reference Priebe, Richardson, Cooney, Oluwatoyin and McCabe36 perhaps reflecting the non-specific factors at play in psychiatry.

The findings here lay out the prospect that training clinicians to ask more declarative questions (or at least certain types) may be one method of improving the therapeutic alliance and subsequent adherence. This hypothesis is based on the direction of effect commonly cited in alliance and adherence research: perceptions of the therapeutic relationship, mediated through talk, may influence adherence. However, given that this particular pathway of causality cannot be confirmed within the scope of a correlational study, an equally interesting alternative is the polar directionality. Through this lens, declaratives represent one possible index for how positive alliances and/or adherence are manifest in interaction (or less favourable alliances, as indexed by ‘wh-’ questions). The alliance and adherence may be independent variables with discursive consequences: psychiatrists might more easily achieve, display and invite confirmation of their ‘understandings’ through declarative questions with patients who are more adherent and engaged with treatment in the first place.

Whichever interpretation is used, each highlights the need to consider the degree of shared understanding established in patient–clinician interaction. This is consistent with our earlier study: patient attempts to check understanding (clarifying what the psychiatrist said in a previous turn) were also associated with better adherence. Reference McCabe, Healey, Priebe, Bremner, Lavelle and Dodwell6 Relatedly, one would expect achieving mutual understanding might be more difficult in people with symptoms such as delusions. This could explain why ‘wh-’ questions – open questions that presuppose less understanding, thereby inviting more extensive responses – were associated with symptoms and poorer psychiatrist alliance ratings. Indeed, discussion of psychotic symptoms can cause considerable interactional tension in out-patient encounters. Reference McCabe, Heath, Burns and Priebe2 Recognising candidate interactional markers of good relationships such as declarative questions might be one of the first steps for developing interventions to improve adherence, derived from naturalistic interaction. Crucially, clinician ratings of the therapeutic alliance in psychiatry have been found to predict more distal outcomes. Reference Priebe, Richardson, Cooney, Oluwatoyin and McCabe36 More abstract notions of ‘patient-centredness’ do not easily translate into measurable communication practices, conducive to training and research.

This study underlines the need for specificity and presents a candidate questioning practice for further analysis. Psychotic symptoms are associated with increased risk of suicide, Reference Palmer, Pankratz and Bostwick37 and treatment non-adherence accounts for approximately 40% of readmission to hospital in the 2 years following discharge from in-patient treatment in schizophrenia, Reference Weiden and Olfson38 incurring substantial clinical and economic burdens. Given that the ultimate goals of interaction in psychiatric settings are the amelioration of such symptoms and the prevention of relapse, the stakes involved in empirically grounded ‘good’ questioning are very high indeed.

Funding

The research was supported by funding from the UK Medical Research Council ().

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of Dr Mary Lavelle and Dr Nadia Strapelli who contributed to the piloting of the coding protocol and/or final coding. The input of Professor Paul Drew and Dr Suzanne Beeke, who commented on an earlier version of this work, is also greatly appreciated.

Appendix

Psychiatrists' ‘so-prefaced’ declarative questions

So you are feeling not so well?

So you feel a bit anxious?

So you're quite happy being on your own?

So you're lethargic, you just couldn't be bothered to do these things?

So you feel okay about it?

So that's something you want to switch off from?

So you are quite happy to continue with the risperidone?

So you're under a lot of pressure at the moment?

So you got a little bit depressed?

So you feel anxious about the amount you're eating?

So you have episodes when you feel really bad?

So you think you're better off?

So you're feeling better in any case?

So the things that you find difficult now are your self-confidence?

So but overall you feel better in yourself?

So I think in terms of what we're doing at the moment you are quite satisfied?

So you're not feeling well?

So these have been helpful?

So on the whole from a psychiatric point of view you're very stable?

So you'd be worried about the antidepressant?

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.