China has a heavy burden of mental health problems such as schizophrenia and depression.Reference Charlson, Baxter, Cheng, Shidhaye and Whiteford1 The total burden of mental, neurological and substance use disorders account for 30% of total disability-adjusted life-years.Reference Charlson, Baxter, Cheng, Shidhaye and Whiteford1 Depression comprises the leading component of such mental health disorders in China.Reference Charlson, Baxter, Cheng, Shidhaye and Whiteford1 However, the current estimates of depression prevalence among adults aged 45 years and older are based on regional surveys.Reference Charlson, Baxter, Cheng, Shidhaye and Whiteford1 Large nationally representative surveys targeting middle-aged and older Chinese adults are needed to accurately estimate the burden of depression and to assist in the better allocation of healthcare resources in China.Reference Charlson, Baxter, Cheng, Shidhaye and Whiteford1 Many factors have been attributed to the striking burden of mental health disorders in China, such as the one child per family policy implemented in the 1980s, unique cultural and social contexts, and dramatic social reforms.Reference Charlson, Baxter, Cheng, Shidhaye and Whiteford1 There is evidence that prenatal exposure to the Chinese Great Famine of 1959–1961 contributes to the high rates of adult schizophrenia.Reference St Clair, Xu, Wang, Yu, Fang and Zhang2 However, the impact of the Chinese Great Famine on depression has not been documented, although early-life nutrition deprivation is an important risk factor for depression.Reference Whitaker, Phillips and Orzol3 Dutch famine studies have demonstrated that prenatal exposure to 6 months' food shortage increased the risk of depression in adult offspring.Reference de Rooij, Painter, Phillips, Räikkönen, Schene and Roseboom4, Reference Stein, Pierik, Verrips, Susser and Lumey5 The 1959–1961 Chinese Great Famine lasted for 3 years and affected the entire country.Reference Huang, Guo, Nichols, Chen and Martorell6 It provides an unparalleled opportunity to study the impact of long-term extreme food shortage during different developmental stages on depression risk in late life. Analysis of a nationally representative cohort will improve our understanding of depression risk in a number of ways. We can identify critical time windows for depression prevention, uncover novel mechanisms of depression development, and help explain the heavy burden of mental health disorders in China. Therefore, the current study aims to estimate the prevalence of depressive symptoms and to evaluate the impact of famine exposure overall and during different developmental stages on depressive symptoms in late adulthood among participants of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS).

Method

Study population and design

The CHARLS is a biannual longitudinal survey of a nationally representative sample of Chinese adults aged 45 years and older.Reference Zhao, Hu, Smith, Strauss and Yang7 It is designed to describe the dynamics of retirement and its impact on health, health insurance and economic well-being in China. The first wave of data was collected between June 2011 and March 2012 by trained interviewers during a face-to-face household encounter. The data consists of comprehensive and detailed information including socioeconomic indicators, biomedical measurements, as well as health status and functional indicators.Reference Zhao, Hu, Smith, Strauss and Yang7

The detailed sampling design of the CHARLS is available elsewhere.Reference Li, Liu, Sun, Wu, Zou and Li8, Reference Feng, Pang and Beard9 Briefly, the survey used a four-stage, stratified, cluster probability sampling design.Reference Zhao, Hu, Smith, Strauss and Yang7 The primary sampling unit (PSU) was administrative villages (cun) in rural areas and neighborhoods (shequ) in urban areas. In the first stage, a random sample of 150 counties was selected to represent the socioeconomic and geographic pattern of all counties. In the second stage, three PSUs were selected in each county with a probability proportional to their population size. In the third stage, a random sample of 24 households was selected among those with residents aged 45 or older in each selected PSU. Finally, for a selected household, one resident was randomly selected as a participant in the survey. If the spouse of the selected resident was aged 45 years or older, the spouse was also included in the survey. Response rate among eligible households was 80.5%.Reference Zhao, Strauss, Yang, Giles, Hu and Hu10 The response rate was higher among rural households than urban households (94.2% v. 68.6%).Reference Zhao, Strauss, Yang, Giles, Hu and Hu10 Overall, a total of 17 708 individuals within 10 257 households were interviewed in the baseline survey.Reference Zhao, Hu, Smith, Strauss and Yang7, Reference Zhao, Strauss, Yang, Giles, Hu and Hu10 The responses of these participants were used in the current analyses.

The Chinese Great Famine occurred between 1959 and 1961. For purposes of this analysis, we selected the start date as 1 January 1959 and the end date as 31 December 1961. We then used this time span to divide the CHARLS participants into eight age-exposure cohorts based on their developmental stages when experiencing the Chinese Great Famine: fetal, infant, toddler, preschool, mid-childhood, young teenage, teenage and adulthood cohorts. Included as the fetal cohort (born or conceived in the famine) were 996 participants born between January 1959 and September 1962. There were 445 participants born in 1958 as the infant cohort (aged 0–1 when famine occurred). Another 1108 participants born in 1956–1957 were included as the toddler cohort (aged 1–2 when famine occurred). Next, there were 1241 born in 1954–1955 as the preschool cohort (aged 3–5 when the famine occurred). There were 3217 born in 1948–1953 as the mid-childhood cohort (aged 6–11 when the famine occurred). The young-teenage cohort (aged 12–14 when the famine occurred) included 1143 born in 1945–1947. There were 887 born in 1942–1944 as the teenage cohort (aged 15–17 when the famine occurred). Finally, there were 2486 born before 1941 as the early-adulthood cohort (aged 18–30 when the famine occurred).

Exposure to the Chinese Great Famine

In the third-wave survey (2014–2015), exposure to the Chinese Great Famine was measured using three items.

(a) Did you and your family experience starvation in 1958–1962?

(b) During those days, did you and your family move away from the famine-stricken area?

(c) During those days, did any of your family members starve to death?

By combining responses to these questions, participants were categorised as exposed to (a) severe famine if they reported death of family member(s) to starvation; (b) moderate famine if they reported starvation or moving away from famine-stricken areas or (c) no famine if they reported having no starvation. For all analyses, the reference group consisted of individuals responding ‘no starvation’.

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) short form was used to measure depressive symptoms in the baseline survey (2011–2012) of the CHARLS.Reference Kohout, Berkman, Evans and Cornoni-Huntley11 The CES-D short form contains the following ten items: (a) being bothered by things that do not usually cause bother; (b) having trouble concentrating; (c) feeling depressed; (d) feeling that everything you did was an effort; (e) feeling hopeful about the future; (f) feeling fearful; (g) being sleepless; (h) feeling happy; (i) feeling lonely; and (j) inability to ‘get going’.

For each item, respondents reported the frequency of occurrence for the item during the past week. To create the CES-D summary, each item was scored on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). Before analysis, item 5 and 8 were reversely scored to match the polarity of the other items. The summed range of CES-D item scores varied from 0 to 30 with higher scores indicating higher levels of depressive symptoms.Reference Kohout, Berkman, Evans and Cornoni-Huntley11 The CES-D short form has been validated among a subsample of 742 CHARLS participants aged 60 years and older showing adequate psychometric properties.Reference Chen and Mui12 In the validation study, a two-factor model fitted the best. The comparative fit index and Tucker–Lewis fit index for the two-factor model were 0.99 and 0.98, respectively and the completely standardised factor loadings were 0.30 and above.Reference Chen and Mui12 To be consistent with the validation study, a score of 12 or higher was used to define depressive symptoms in the current analysis.Reference Chen and Mui12

Covariates in the baseline survey

Demographic and socioeconomic variables

Demographic and social economic variables, including age, gender, education level, childhood location (rural v. urban), current location (rural v. urban), marital status, self-perceived family income level, employment status and individual income sources, were measured by self-report. Education categories included ‘illiterate’, ‘less than elementary school’, ‘elementary school’, ‘middle school’ and ‘high school or above’. The question ‘Where did you mainly live before you were 16 years old? Is it in a village or city/town?’ formed the basis for categories of childhood location. Marital status included the following categories: currently married (including ‘married and live together’ and ‘married but temporarily separated’) and currently not married (including ‘separated’, ‘divorced’, ‘widowed’ and ‘never married’). Self-perceived family income categories included ‘average and above’, ‘relatively poor’ and ‘poor’. Respondents were either ‘currently employed’ or ‘currently not employed’. Finally, individual income sources included three categories ‘wage, bonus and others’, ‘others’ and ‘none’.

Lifestyle and personal health-related behaviours

Lifestyle and personal health-related behaviours, including drinking and smoking, were collected using a standardised questionnaire.Reference Zhao, Hu, Smith, Strauss and Yang7 There were four drinking status categories: currently regular drinkers, currently occasional drinkers, former drinker and never drinkers. To distinguish between regular and occasional drinkers, we calculated the average standard glasses of alcoholic beverage per week. One standard glass of alcoholic beverage was equivalent to 15 grams of alcohol, corresponding to approximately 500 mL of beer, 150 mL of wine and 50 mL of liquor. A summary amount of alcohol consumed was calculated by combining drinking frequency and volume per week. Currently regular drinkers consumed more than two standard glasses of alcoholic beverage per week. Those having two or fewer standard glasses of alcoholic beverage per week were classified as currently occasional drinkers. Smoking categories included current smokers, former smokers and never smokers.

Biomedical measures

Biomedical measures included blood pressure, body weight and height. Blood pressure was measured three times for each participant by trained observers according to standard protocol after the participant rested for 30 min.Reference Zhao, Strauss, Yang, Giles, Hu and Hu10 We used the mean of three measures for analyses. With participants in light indoor clothes, body weight and height were measured using a health meter (Omron™ HN-286) and a stadiometer (Seca™ 213), respectively. Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters.

Comorbidities

Comorbidities were measured by self-reported responses to the question ‘Have you EVER been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have XX?’. Choices for chronic conditions included hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes, cancer or malignant tumour (excluding minor skin cancers), chronic lung diseases (except for tumours or cancer), liver diseases (except for fatty liver disease, tumours or cancer), cardiovascular diseases (including heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure or other heart problems), stoke, kidney disease (except for cancer or tumour), stomach or other gastrointestinal diseases (except for tumour or cancer), arthritis and asthma.

Statistical analysis

Prevalence of depressive symptoms and severe famine

When estimating prevalence and their corresponding standard errors, we took into consideration the complex survey design and non-response rate in both estimates. We also created 5-year age groups for purposes of analyses. The SAS PROC SURVEYFREQ procedure generated the overall and gender-specific prevalence of depressive symptoms and severe famine exposure among all the participants and for the 5-year age groups.

Associations between famine exposure and depressive symptoms

Continuous variables are shown as means and standard deviations, and categorical variables are shown as percentages. Variables of interest included demographics factors, socioeconomic status, self-reported diseases, biomedical measures and health-related behaviours. Bivariate association analyses were conducted between famine severity levels and these variables among the overall participants using χ2-tests for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables.

Multinomial propensity score matching was used to generate weights that estimated the average treatment effect by balancing the included covariates across multiple groups and allowed pairwise comparisons among the three famine severity groups.Reference Stuart13–Reference McCaffrey, Griffin, Almirall, Slaughter, Ramchand and Burgette15 The weights were the reciprocal of the probability that a study participant was exposed to the corresponding famine severity based on covariates included in the matching. We generated two sets of weights. The first weight was generated using age, gender, education and childhoodlocation (rural/urban), and the second weight using all covariates mentioned above. After weighting, the covariate distributions in all the three famine severity groups were more similar compared with the original sample. Since the prevalence of depressive symptoms was more than 10% in the study population, odds ratio from a logistic regression model overestimates the risk ratio (RR).Reference Zou16 Therefore, we used the modified Poisson regression models to estimate the risk ratio and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals associated with moderate and severe famine exposure, respectively,Reference Zou16 and incorporated the calculated weights into the Poisson models.

To identify important time windows when famine had a stronger impact on late adulthood depressive symptoms, we further evaluated associations between moderate and severe famine exposure and depressive symptoms in each age-exposure cohort. We built two models in each age-exposure cohort using the modified Poisson regression. Model 1 adjusted for demographic variables, including age, gender, education and childhood location (rural/urban). Model 2 was the fully adjusted model with all variables controlled. The modified Poisson regression did not converge for model 2; therefore, model 2 was a multivariate logistic regression. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were presented for variables in the logistic regression models.

Impact of severe famine exposure at different fetal ages

Food shortage gradually occurred at the end of 1958. Therefore, we used 1 January 1959 as the start point of the Chinese Great Famine. To identify critical periods of exposure during pregnancy, we tested the association of severe famine with subsequent depressive symptoms by trimesters among participants born in 1959. Individuals born in the first 4 months of 1959 was treated as exposed to severe famine in the third trimester, those born in May, June and July as exposed since the second trimester, and those born between August and December as exposed since the first trimester. To evaluate whether longer duration of severe famine exposure during the fetal stage had greater impact on depressive symptoms, we further calculated associations of severe famine with depressive symptoms according to length of severe famine exposure during the fetal stage, from ≤3 months to ≤10 months in 1959. As a result of the limited number of participants born in 1959, we only adjusted for age, gender and childhood rural/urban location in these analyses using logistic regression models.

We also evaluated associations of severe famine exposure during the entire pregnancy and at least the first 3 months of pregnancy, respectively, with depressive symptoms in late adulthood. To assess the joint effect of parents' long-term exposure to severe famine and fetus' exposure to famine during the first 3 months, we tested famine–depressive symptoms associations among participants who were conceived during the last 3 months of the Chinese Great Famine. For all these analyses, we built the same two models as in our main analyses.

Percentage population-attributable risk of depressive symptoms as a result of the Chinese Great Famine

We estimated the prevalence of severe and moderate famine exposure, respectively, among the overall participants using the SAS PROC SURVEYFREQ procedure taking into account the complex study design and response rate. The percentage population-attributable risk of depressive symptoms because of the Chinese Great Famine in the middle-aged and older Chinese population was estimated using the following formula,Reference Walter17

where P 1 and P 2 are prevalence of moderate and severe famine exposure, respectively, and RR 1 and RR 2 are the corresponding RRs estimated from the modified Poisson regression models weighted by propensity scores matching on all covariates.

We used SAS 9.3 to perform data analyses. All P-values were two-sided, and P<0.05 was considered significant.

Ethics statement

The CHARLS study data is publicly available and open to researchers all over the world. The current study uses secondary analyses of the de-identified CHARLS study data. The institutional review boards at the University of Georgia granted the current study exemption from review.

Results

Characteristics of the CHARLS participants are shown by levels of famine exposure (supplementary Table 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.116), and variables that significantly differed by famine severity levels are demonstrated in Table 1. In the overall cohort, participants were more likely to be women and had an average age of 61.5 years old. Most of the participants lived in rural areas (80.6%) and were married (87.8%). Only 11.4% of the participants had high school or above education. The proportion of current smokers was 29.8% and 16.0% were currently regular drinkers. Participants had an average normal weight (mean body mass index 23.3 kg/m2) and over 60% reported having at least one chronic conditions.

Table 1 Characteristics that significantly differed by famine status among the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study participants in the 2011 baseline survey

BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

a. Severe famine defined as one or more member of the family died from starvation between 1959 and 1961.

b. Depressive symptoms defined as Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale score ≥12.

Prevalence of depressive symptoms

There were 15 541 participants (87.8% of the CHARLS cohort) with no missing measurement of CES-D-10 scores. As shown in Table 2 and supplementary Fig. 1, the overall prevalence of depressive symptoms was 26.2% (95% CI 25.1–27.3%) and there was significant gender difference (men v. women: 20.3 v. 31.5%, P<0.001). Respondents aged 80 years and older had the highest prevalence of depressive symptoms, with 30.8% (95% CI 26.4–35.2%) of men and 40.5% (95% CI 34.4–46.6%) of women having depressive symptoms. In addition, prevalence rates were greater among rural residents compared with urban residents for both men and women.

Table 2 Prevalence of depressive symptoms (China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) 2011) and exposure to severe famine (CHARLS, 2014) by gender and location

a. Depressive symptoms defined as Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale short form score ≥12.

b. Severe famine defined as one or more member of the family died from starvation between 1959 and 1961.

Prevalence of exposure to severe famine

There were 12 910 participants (83.1%) in the third-wave survey in 2014–2015, which contained items of exposure to the Chinese Great Famine. As shown in Table 2 and supplementary Table 2, the overall prevalence of exposure to severe famine was 11.6% (95% CI 10.1–13.1%). Participants aged 65–70 years old had the highest prevalence of exposure to severe famine (16.6%, 95% CI 12.0–21.2%). There were significant gender differences in three age groups: men had higher prevalence of severe famine exposure in the 65–70 age groups, whereas women had much higher prevalence in the 50–55 and 70–75 age groups.

Associations between famine and depressive symptoms

As shown in Table 1, the prevalence of depressive symptoms increased with the severity of famine (P<0.001). After propensity score matching for age, gender, education level and childhood urban/rule location, participants exposed to moderate and severe famine were 1.22 (95% CI 1.17–1.27) and 1.48 (95% CI 1.42–1.54) times, respectively, more likely to have depressive symptoms in late adulthood. When further matching on all covariates, individuals who had moderate and severe famine exposure were 1.17 (95% CI 1.08–1.29) and 1.34 (95% CI 1.20–1.51) times, respectively, more likely to have depressive symptoms.

Table 3 and supplementary Fig. 2 shows the results of analyses by developmental stages. After adjustment for age, gender, education level and childhood urban/rural location, modified Poisson regression analyses demonstrate that participants exposed to moderate and severe famine during the fetal stage were 1.16 (95% CI 0.90–1.49) and 1.87 (95% CI 1.36–2.55) times, respectively, more likely to have depressive symptoms in late adulthood. There was significant linear trend of depressive symptoms prevalence across severities of famine (P = 0.002) in the fetal cohort. Significant linear trends were also identified in mid-childhood (P<0.001), young-teenage (P = 0.01) and early-adulthood (P<0.001) cohorts. In these cohorts, moderate and severe famine exposure were associated with 1.32 (95% CI 1.08–1.61) and 1.54 (95% CI 1.23–1.94), 1.17 (95% CI 0.89–1.52) and 1.47 (95% CI 1.09–2.00), and 1.37 (95% CI 1.14–1.66) and 1.77 (95% CI 1.42–2.21) times higher likelihood of having depressive symptoms in late adult life, respectively. In the fully adjusted logistic regression models (Table 3 and supplementary Table 3), significant linear trends between famine severity and prevalence of depressive symptoms remained for the fetal (P = 0.03), mid-childhood (P = 0.02), young-teenage (P = 0.02) and early-adulthood cohorts (P < 0.001). There was no significant association between famine and depressive symptoms in infant (P = 0.76), toddler (P = 0.44), preschool (P = 0.12), or teenage (P = 0.89) cohorts.

Table 3 Associations of exposure to the Chinese Great Famine with depressive symptoms in late adulthood overall and by developmental stages among participants of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

a. Age, gender, education, childhood location (rural/urban), current location (rural/urban), marital status, self-perceived family income level, individual income sources, employment status, smoking, drinking, body mass index, diastolic blood pressure, lung disease, chronic kidney disease, digestive diseases and arthritis were matched for or controlled for in the models.

Impact of famine at different fetal ages

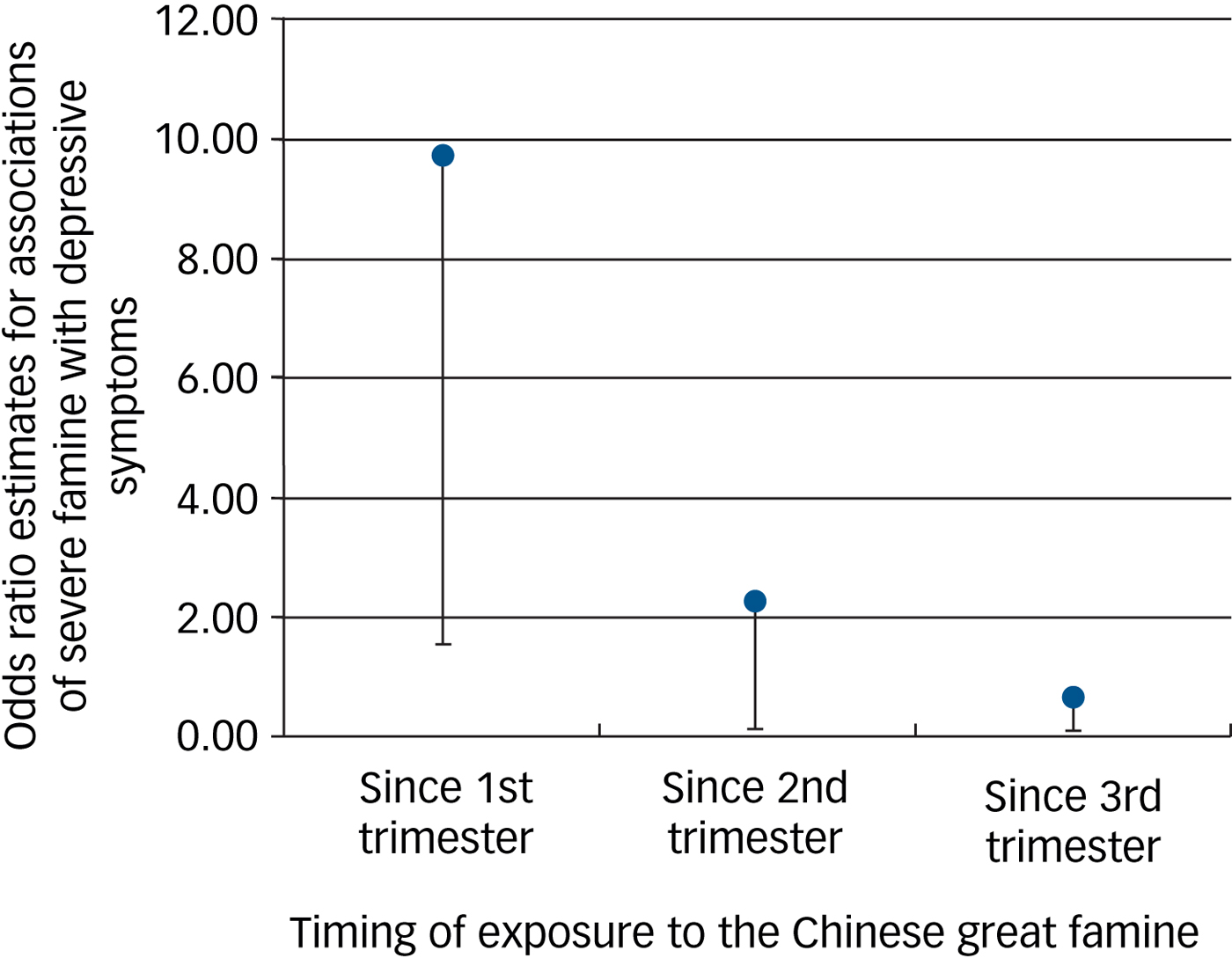

As shown in Fig. 1, exposure to severe famine since the first trimester was associated with 9.7 greater odds of having depressive symptoms in late adulthood. If exposed since the second trimester, severe famine was associated with 2.3 greater odds of having depressive symptoms. Among those exposed in the last trimester, the association of severe famine with depressive symptoms was very weak (OR ≈ 1). In addition, individuals experiencing severe famine for at least the entire first trimester had 2.86 (95% CI 1.61–5.08) greater odds of getting depressive symptoms in late adulthood among the overall participants. For those who were exposed to severe famine during the entire pregnancy, there was 3.39 (95% CI 1.65–6.97) greater odds of having depressive symptoms in late adulthood. We further demonstrated that (supplementary Table 4), for individuals conceived in the last 3 months of the Chinese Great Famine, severe famine had an even larger effect on depressive symptoms (OR = 5.92, 95% CI 1.59–22.09).

Fig. 1 Associations of severe famine with depressive symptoms in late adulthood by pregnancy trimesters when the famine occurred.

Population-attributable risk because of famine exposure

The prevalence of exposure to moderate famine was 69.2% and exposure to severe famine was 11.6% in the overall study population. Meanwhile, participants who were exposed to moderate famine and severe famine were 1.17 (95% CI 1.08–1.29) and 1.34 (95% CI 1.20–1.51) times, respectively, more likely to develop depressive symptoms in late adulthood in the fully adjusted propensity score matching analyses. Therefore, in the middle-aged and older Chinese population, 13.6% of the overall depressive symptoms can be attributable to early-life famine exposure.

Discussion

Main findings

In the largest ever study on early-life exposure to the Chinese Great Famine and late-adulthood prevalence of depressive symptoms in a middle-aged and older Chinese population using individual-level data, we identified that exposure to the famine was associated with depressive symptoms in late adulthood. We further revealed that famine experience during fetal, mid-childhood, young teenage and early adulthood stages was positively associated with depressive symptoms in late adult life, whereas famine experience during infant, toddler, preschool and teenage stages was not associated with depressive symptoms in late adulthood. Sensitivity analysis revealed that in the fetal stage, the first and second trimesters, not the third trimester, were critical time windows where famine had a stronger association with depressive symptoms in late adulthood. In addition, we demonstrated that 11.6% of the middle-aged and older Chinese population experienced severe famine in 1959–1961, and 26.2% had depressive symptoms. Overall, 13.6% of the depressive symptoms among the middle-aged and older Chinese adults can be attributed to the Chinese Great Famine.

Impact of exposure to famine at the fetal stage and comparison with findings from other studies

We demonstrated that the first and second trimesters were the key time windows during the fetal stage where exposure to severe famine was strongly associated with depressive symptoms in late adulthood, whereas famine in the last trimester had a very weak association with depressive symptoms. The Dutch famine study has reported that individuals born in or around the 6 months' Hunger Winter had increased risk for depressive symptoms in late adulthood.Reference de Rooij, Painter, Phillips, Räikkönen, Schene and Roseboom4, Reference Stein, Pierik, Verrips, Susser and Lumey5 Our study contributes further robust evidence that long-term exposure to famine (3 years) was strongly associated with depressive symptoms in late adulthood in a Chinese population. More importantly, our study was able to demonstrate the first two trimesters, particularly the first trimester, were a critical time window in which famine exerted effect on depressive symptoms in late adulthood. In addition, our study also identified that famine had the greatest effect on depressive symptoms among individuals who were conceived in the last three months of the Chinese Great Famine. This indicates that long-term maternal and fetal experience of severe famine may have a joint impact on the offspring's risk for depressive symptoms in late adulthood.

Similar to our study, St Clair and colleagues reported that following prenatal exposure to the Chinese Great Famine of 1959–1961 there were higher rates of adult schizophrenia in a regional survey in the Wuhu region of Anhui province, one of the most affected provinces.Reference St Clair, Xu, Wang, Yu, Fang and Zhang2 Our study provides additional evidence that famine experience may have an impact on other mental disorders in this population. Fetal stage is critical in human development. In this stage, genome-wide demethylation occurs and human embryo develops.Reference Guo, Zhu, Yan, Li, Hu and Lian18 Famine may have affected the demethylation process.Reference Tobi, Goeman, Monajemi, Gu, Putter and Zhang19–Reference Heijmans, Tobi, Stein, Putter, Blauw and Susser21 In addition, methylations in certain regions of the human genome can persist for a life time and may have been involved in the aetiology and clinical manifestation of depression.Reference Córdova-Palomera, Fatjó-Vilas, Gastó, Navarro, Krebs and Fañanás22, Reference Nemoda, Massart, Suderman, Hallett, Li and Coote23 However, the role of DNA methylation in famine and the association with depression has rarely been investigated. Further studies in this area may help to find novel mechanisms underlying depression risk.

Impact of exposure to famine from mid-childhood to early adulthood

Besides the fetal stage, our study revealed that famine was also associated with depressive symptoms among those exposed to famine during mid-childhood, young teenage or early adulthood. Interestingly, these periods correspond to recent studies of human brain development in early life. During these stages, structural brain development consists of increased white matter volume and enhanced functional brain development as measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging.Reference Haartsen, Jones and Johnson24 The Chinese Great Famine represents extreme stress because of nutrition deprivation. Findings from the current study suggest that nutrition, stress, or the combination of them both, are more important in these stages. Intervention strategies aiming at reducing stress or improving nutrition supply during these developmental stages may help to reduce risk for depressive symptoms.

Mid-childhood is a key period when a crucial shift in cognitive skills occurs.Reference Eccles25 It is also the period that children develop skills in learning, reasoning and understanding.Reference Eccles25 These skills are essential in social and academic success. Hayden and colleagues have shown that meaningful and stable vulnerability to depression occurrs as early as in the mid-childhood period.Reference Hayden, Olino, Mackrell, Jordan, Desjardins and Katsiroumbas26 Furthermore, nutrition has an important role in children's behavioural outcomes at this stage.Reference Gispert-Llaurado, Perez-Garcia, Escribano, Closa-Monasterolo, Luque and Grote27 Our study provides the first evidence that mid-childhood nutrition deprivation has a long-term effect on depressive symptoms in late adulthood. The early-teen years are marked by rapid changes in physical, cognitive and emotional functions.Reference McNeely and Blanchard28 Stress and the ways in which young teens cope with stress have significant long-term consequences such as depression.Reference McNeely and Blanchard28 In addition, stress increases risk of depression in adolescence, which in turn predicts a range of mental health disorders in adulthood.Reference Fergusson, Horwood, Ridder and Beautrais29

It is surprising that exposure to famine during infant, toddler, preschool and teenage stages were not associated with depressive symptoms in late adulthood. For the infants, toddlers and preschool children, this may be because psychosocial skills were not developed during these stages (1–5 years old), and with care from their parents, they were less likely to sense stress from the Chinese Great Famine. It is unclear why famine experienced during the teenage stage was not associated with depressive symptoms in late adulthood. Future studies are warranted to confirm our finding and delineate potential mechanisms.

Prevalence of depressive symptoms

Our study also provided accurate estimates of the prevalence of depressive symptoms and severe famine experience among the middle-aged and older population in China. The current prevalence estimate for depressive symptoms is much higher than that of 6% reported in a four-province survey in 2009,Reference Phillips, Zhang, Shi, Song, Ding and Pang30 but is similar to findings from a meta-analyses by Li and colleagues in which the prevalence of depressive symptoms was estimated to be 23.6% in Chinese older adults.Reference Li, Zhang, Shao, Qi and Tian31 A systematic review by Gu and colleagues also reported a similar lifetime prevalence of depressive symptoms of 33% and a 12-month prevalence of 23%.Reference Gu, Xie, Long, Chen, Pan and Yan32 The CHARLS is a nationally representative survey conducted in all 28 provinces in China, therefore, our study provided a direct estimate of depressive symptom burden in middle-aged and older Chinese adults, and indicates that depressive symptoms are a major public health challenge in China. More healthcare resources should be allocated to address this issue.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has important strengthens. First, it is the largest famine study using a nationwide representative sample in China. Therefore, findings from the current study are generalisable to the entire country. Second, it is the first study on the Chinese Great Famine to use individual reports as famine exposure data. Previous investigations on the Chinese Great Famine were all ecological studies that compared participants from areas of different famine severities. Ecological fallacy in those studies could not be ruled out. Our study has collected famine severity data from individual participants, and ecological fallacy was avoided. Third, we are the first study that focused on famine experience in different birth cohorts, from fetal to early adulthood. Previous famine studies have focused on prenatal exposure to famine, and very few studies have reported on famine's impact on older children and younger adults. This is mainly because famine in other countries was short and on a small scale. The Chinese Great Famine lasted for more than 3 years and affected the entire mainland China, which provides an unparalleled opportunity to study famine's impact during different developmental stages on depressive symptoms in late life.

Certain limitations should also be acknowledged. Famine experience was based on self-report. For younger cohorts, such as those born during famine, famine experience is an intergenerational story told by family survivors. Therefore, there might be some recall bias about famine experience. However, recall of dramatic life events, such as starving to death or moving to other areas because of famine should be reliable.

In conclusion, 26.2% of middle-aged and older Chinese adults had depressive symptoms, and 11.6% of this population experienced severe famine during 1959–1961. Famine experienced during the fetal, mid-childhood, young-teenage and early-adulthood stages was associated with an increased prevalence of depressive symptoms in late adulthood, which partly explains the high burden of mental disorders in older Chinese adults.

Funding

S.L. is partly supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1P20GM109036-01A1).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Peking University National Center for Economic Research for providing the CHARLS data. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.116.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.