High-risk research is a method of studying the aetiology and early antecedents of a disorder by investigating individuals who are at increased risk of developing it, typically those with a family history of the disorder (for review, see Reference Niemi, Suvisaari and Tuulio-HenrikssonNiemi et al, 2003). One of the aims of high-risk research into schizophrenia is to determine the disorders to which individuals with a psychotic parent have increased susceptibility. The Helsinki High-Risk Study began in 1974 and is one of the largest-ever high-risk investigations. Being based on information derived from several registers and their records, and on hospital and out-patient unit case notes rather than face-to-face assessments, the study sample has included all eligible mothers and their offspring. The aim of this follow-up was to evaluate the cumulative incidences of hospital-treated DSM–IV Text Revision (DSM–IV–TR) Axis I disorders among the high-risk and control offspring, as a function of maternal DSM–IV–TR diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

METHOD

Identification of the cohort

In 1974, all women born between 1916 and 1948 who had been treated for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or other schizophreniform disorder in any of the psychiatric hospitals in Helsinki up to 1974, and who had given birth in Helsinki between 1960 and 1964, were identified from the central archives of psychiatric hospital care in Helsinki, Finland (Reference Wrede, Mednick and HuttunenWrede et al, 1980; Reference WredeWrede, 1984). Their offspring, born in the years 1960–1964, formed the high-risk group. Of the 192 women identified, we were able to find the social security numbers of 183 (born between 1918 and 1946). The control group was formed by locating for each high-risk offspring the previous same-sex birth at the same maternity hospital.

For the adulthood follow-up we collected developmental, social, occupational and psychiatric outcome information. Information on mental disorders was obtained from two sources. Data on hospital treatments from 1969 to 1999 (age of offspring 35–39 years, age of mothers 53–81 years), and after 1995 on all in-patient detoxification treatments in social welfare institutions, were derived from the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register; Statistics Finland provided data on causes of death and death certificates up to 2000.

Diagnostic assessment

From the register information, all case records from hospital and out-patient treatments were collected and assessed separately by two psychiatrists (L.T.N. and J.M.S.), followed by a consensus diagnosis based on the DSM–IV–TR criteria. Diagnostic assessment was similar for the high-risk and control mothers, fathers and offspring, and consisted of assigning a DSM–IV–TR diagnosis, and completing the Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Illness (OPCRIT; Reference McGuffin, Farmer and HarveyMcGuffin et al, 1991), the Major Symptoms of Schizophrenia Scale (MSSS; Kendler, 1993a), the global ratings of anhedonia–asociality and of avolition–apathy on the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS; Reference AndreasenAndreasen, 1982) and the global rating of bizarre behaviour on the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS; Reference AndreasenAndreasen, 1984). For all case notes, L.T.N. completed the whole assessment procedure; J.M.S. assigned DSM–IV–TR diagnoses for all case notes, but completed the whole procedure only for the first 20 cases and thereafter for every fifth case note. In cases of disagreement, the case records were reassessed by both authors, and consensus ratings made. The κ values for schizophrenia, schizophrenia-spectrum disorder, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder were 0.69 (95% CI 0.61–0.79), 0.42 (95% CI 0.25–0.60), 0.47 (95% CI 0.29–0.65), 0.57 (95% CI 0.36–0.79) and 0.48 (95% CI 0.23–0.73), respectively. Offspring were grouped according to the most severe maternal diagnosis, the four groups being schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, other schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and affective disorders.

High-risk group

The original case selection was made according to ICD–8 diagnoses (Reference Wrede, Mednick and HuttunenWrede et al, 1980). Our revision on the basis of DSM–IV–TR identified 92 of the 183 women as having schizophrenia, 18 with schizoaffective disorder, 20 with psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (NOS), 1 with brief psychotic disorder, 6 with schizophreniform disorder, 1 with schizotypal personality disorder, 16 with bipolar I disorder, 4 with major depressive disorder with psychotic features, 1 with major depressive disorder without psychotic features and 2 with mood disorder NOS. Because the sample sizes of separate affective disorders were small, we formed one group by combining bipolar I disorder with or without psychotic features, major depressive disorder with or without psychotic features, and mood disorder NOS (n=23). Similarly, cases of psychotic disorder NOS, schizophreniform disorder, schizotypal personality disorder and brief psychotic disorder were combined to form the group of other schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (n=28). Mostly because the case notes had been destroyed, we were unable to assign a diagnosis for 22 women (with 24 offspring).

The final sample consisted of 161 mothers with 179 offspring. For 149 offspring, the father was identified (altogether 132 fathers); for the remainder the father was unknown to the population register. The final control group consisted of 176 offspring, 176 mothers and 176 fathers. Three controls were missing because of identification problems. One of the control group mothers had developed schizophrenia, and two had a psychotic disorder NOS, but their children had no history of psychiatric hospitalisation.

Statistical assessment

Age at onset of illness was recorded using the OPCRIT definition, as the earliest age (nearest year) at which medical advice was sought for psychiatric reasons. The duration of treatment contact was calculated from the earliest to the latest date of medical contact for psychiatric reasons. For most individuals, our information about their treatment contacts spanned several years and was quite detailed. All statistical analyses were performed using S-PLUS statistical software (MathSoft, 1996). Differences in the background demographic variables between groups were tested with likelihood ratio statistics using the χ2 distribution. For comparing the means between groups we used the F-test. Differences in the proportions were modelled using logistic regression, tested with likelihood ratio statistics using the χ2 distribution, and reported as odds ratios (ORs). Incidences were modelled using the Poisson regression and tested with likelihood ratio statistics using the χ2 distribution, and their differences were reported as relative risks (RRs). All tests were two-tailed, with α set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographic information on the women in the high-risk and control groups is presented in Table 1; Table 2 gives information on the offspring. In most cases in all groups, the mother's first hospitalisation for psychiatric reasons was after the birth but before the child reached school age. The proportion of offspring who had been hospitalised for psychiatric reasons was highest in the maternal schizophrenia group (27.0%), followed by the schizo-affective (20.0%) and schizophrenia-spectrum disorder (20.0%) groups, and lowest in the affective disorder (8.0%) and control groups (11.8%). Two offspring in the high-risk groups had died before 16 years of age: one from the schizophrenia group and the other from the schizophrenia-spectrum disorder group.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of women in the high-risk and control groups

| High-risk group | Control group (n=176) | Statistical test1 | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia (n=92) | Schizoaffective disorder (n=18) | Other schizophrenia-spectrum disorder (n=28) | Affective disorder (n=23) | ||||

| Mother's age at birth of index child, years: mean | 27.9 | 26.7 | 28.1 | 27.1 | 27.3 | F 1.3=0.39 | 0.82 |

| Father's age at birth of index child, years: mean | 31.1 | 33.0 | 29.8 | 29.2 | 29.5 | F 1.3=1.48 | 0.21 |

| Number of children, n: mean | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.7 | F 1.3=2.16 | 0.073 |

| Mother married at the birth of index child, % | 88.5 | 80.0 | 96.7 | 96.0 | 96.0 | χ2(5)=11.85 | 0.019 |

| Age at onset of first psychiatric hospitalisation, years | |||||||

| Mean | 28.8 | 30.1 | 32.1 | 27.9 | 37.02 | F 1.3=2.39 | 0.053 |

| Median | 28.0 | 31.0 | 33.0 | 26.0 | 33.02 | ||

| Duration of treatment contact, years | 26.6 | 27.4 | 11.9 | 18.3 | 10.32 | F 1.3=11.57 | 0.0001 |

Table 2 Demographic characteristics of offspring in the high-risk and control groups

| High-risk group | Control group (n=176) | Statistical test1 | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia (n=104) | Schizoaffective disorder (n=20) | Other schizophrenia-spectrum disorder (n=30) | Affective disorder (n=23) | ||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male/female, n/n | 61/43 | 11/9 | 14/16 | 12/13 | 98/78 | χ2(4)=1.92 | 0.75 |

| Male, % | 58.7 | 55 | 46.7 | 48.0 | 55.7 | ||

| Hospital treatment because of any psychiatric disorder, n (%) | 28 (27.0) | 4 (20.0) | 6 (20.0) | 2 (8.0) | 21 (11.9) | F 1,3=21.24 | <0.0001 |

| Duration of treatment contact, years | |||||||

| Mean | 9.6 | 6.0 | 24.7 | 11.2 | 3.6 | F 1,3=5.69 | <0.0001 |

| Median | 6.6 | 4.6 | 19.7 | 8.5 | 0.78 | ||

| Index child's age at mother's first hospitalisation, years2 | |||||||

| Mean | 3.9 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 13.3 | χ2(4)=11.9 | 0.018 |

| Median | 4.4 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 18.4 | ||

| Father not known, n (%) | 20 (19.2) | 6 (30) | 2 (6.7) | 3 (12) | 0 (0) | χ2(4)=51.1 | <0.0001 |

The odds of the father having any psychiatric disorder were higher in the high-risk groups than in the control group (OR=2.57, 95% CI 1.32–5.00, χ2(1)=8.04; P=0.0046), and their odds of having alcohol or other substance abuse or dependence were more than three times greater (OR 3.36, 95% CI 1.26–9.00, χ2(1)=6.42; P=0.011). Other Axis I disorders were not more common among fathers in the high-risk group (Table 3). In one family, both parents had schizophrenia.

Table 3 Lifetime DSM–IV–TR diagnoses in high-risk and control group parents and offspring

| Diagnosis | High-risk group | Control group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother (n=161) | Father (n=132) | Offspring (n=179) | Mother (n=176) | Father (n=176) | Offspring (n=176) | |

| Schizophrenia | 92 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 18 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Schizophreniform disorder | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Schizotypal personality disorder | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Delusional disorder | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brief psychotic disorder | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Psychotic disorder not otherwise specified | 20 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Bipolar I disorder, with psychotic features | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Bipolar I disorder, without psychotic features | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Major depressive disorder, with psychotic features | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Major depressive disorder, without psychotic features | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Other mood disorders | 49 | 2 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 4 |

| Anxiety disorders | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 17 | 13 | 15 | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| Other substance abuse or dependence | 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Alcohol or substance-induced psychotic disorders | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Other alcohol or substance-induced disorders | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mental retardation | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Suicide | 6 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Other psychiatric disorders | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Diagnosis deferred because of inadequate information | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

Cumulative incidences of Axis I disorders among offspring

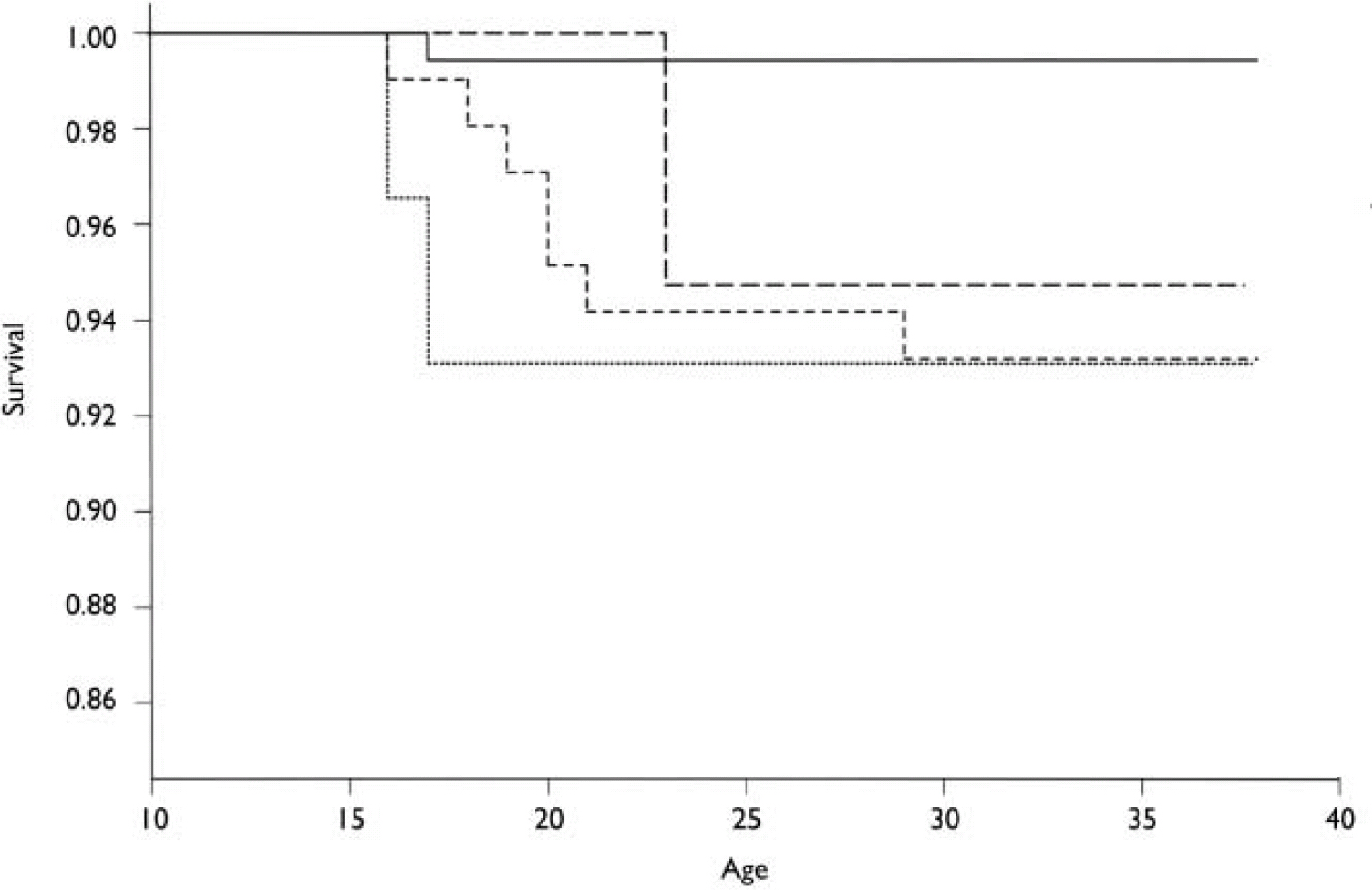

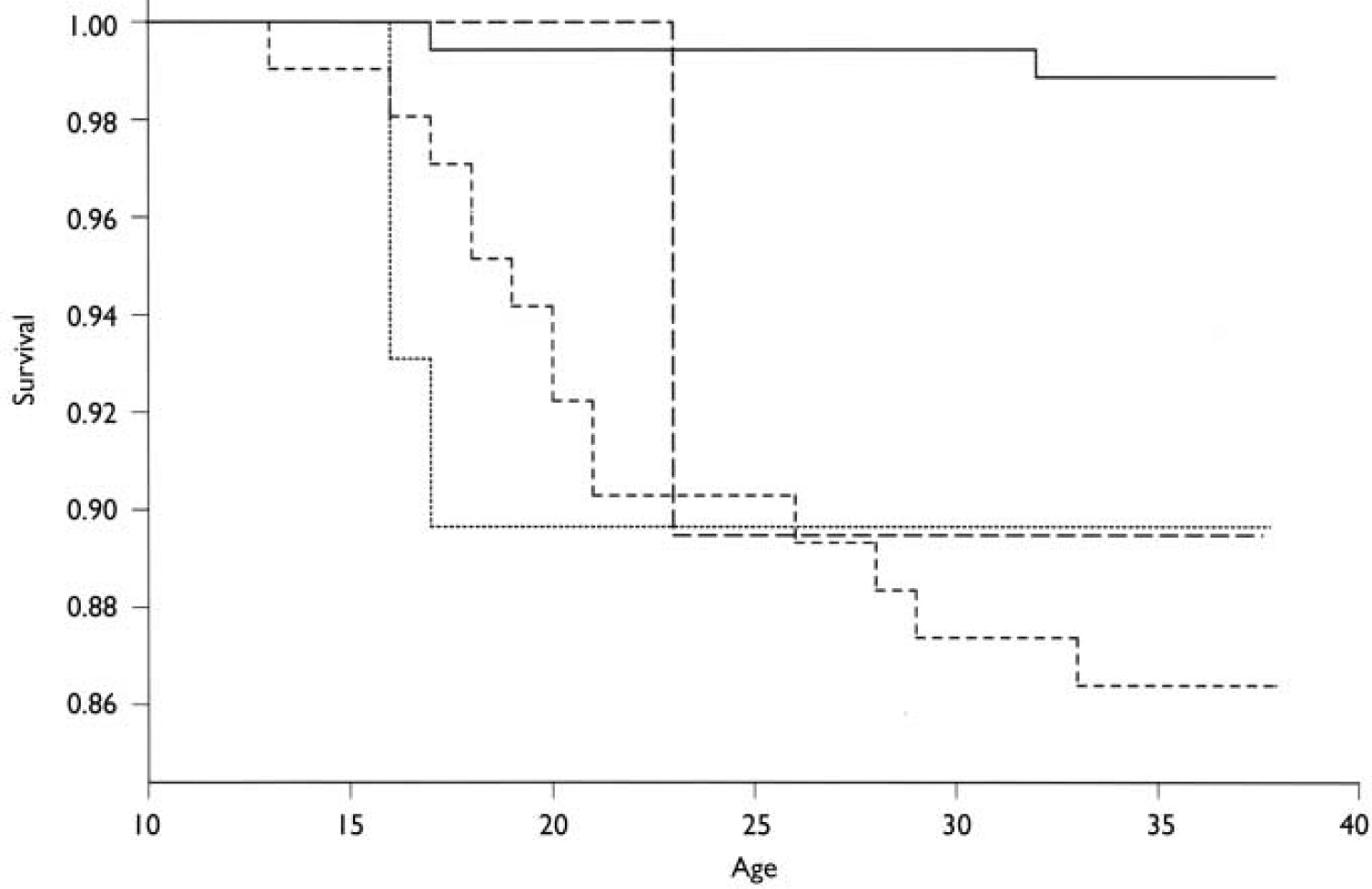

The cumulative incidences of schizophrenia were 6.7% (RR v. controls=12.3, 95% CI 1.52–>100), 5.0% (RR=9.26, 95% CI 0.58–148.12), 6.7% (RR=12.5, 95% CI 1.14–138.1) and 0.57% among offspring of mothers with schizophrenia, schizo-affective disorder, other schizophrenia-spectrum disorder and controls, respectively (Table 4). None of the offspring of mothers with affective disorder developed schizophrenia. The cumulative survival probability from schizophrenia is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Kaplan–Meier cumulative survival probability for schizophrenia developing in offspring in the high-risk and control groups. —, controls; – – –, offspring of mothers with schizoaffective disorder; - - -, offspring of mothers with schizophrenia; ·······, offspring of mothers with other schizophrenia-spectrum disorders.

Table 4 Offspring DSM–IV–TR diagnoses and cumulative incidences in different high-risk maternal diagnostic groups

| Diagnosis | Cases and cumulative incidence, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia1 (n=104) | Schizoaffective disorder (n=20) | Other schizophrenia-spectrum disorder (n=30) | Affective disorder (n=25) | Diagnosis deferred (n=24) | |

| Schizophrenia | 7 (6.7) | 1 (5.0) | 2 (6.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 1 (1.9) | 1 (5.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Schizophreniform disorder | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Delusional disorder | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Brief psychotic disorder | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Psychotic disorder not otherwise specified | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 1 (3.3) | 0 | 1 (4.2) |

| All schizophrenia-spectrum disorders | 11 (10.6) | 2 (10.0) | 3 (10.0) | 0 | 1 (4.2) |

| Bipolar I disorder, with psychotic features | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 0 |

| Major depressive disorder, with psychotic features | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Major depressive disorder, without psychotic features | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 3 (10.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Other mood disorders | 9 (8.7) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (4.0) | 0 |

| Anxiety disorders | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 0 |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 11 (10.6) | 1 (5.0) | 3 (10.0) | 0 | 3 (12.5) |

| Other substance abuse or dependence | 5 (4.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (8.3) |

| Alcohol or substance-induced psychotic disorders | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 2 (6.7) | 0 | 1 (4.2) |

| Other alcohol or substance-induced disorders | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mental retardation | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Suicide | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.0) | 0 |

| Other psychiatric disorder | 1 (1.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All non-psychotic disorders1 | 11 (10.6) | 2 (10.0) | 3 (10.0) | 2 (8.0) | |

| All mental disorders1 | 24 (23.1) | 4 (20.0) | 6 (20.0) | 3 (12.0) | 12 (6.9) |

| Diagnosis deferred because of inadequate information | 4 (3.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.2) |

The cumulative incidences of any psychotic disorder were 13.5% (RR=12.6, 95% CI 2.87–55.5), 10.0% (RR=9.42, 95% CI 1.35–66.9), 10.0% (RR=9.57, 95% CI 1.60–57.3), 4.0% (RR=3.60, 95% CI 0.33–39.70) and 1.14% among offspring of mothers with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, other schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, affective disorders and controls, respectively (Table 4). After combining the groups of women with schizophrenia and those with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, the cumulative incidence of any psychotic disorder among their offspring was 12.3% (RR=11.61, 95% CI 2.71–49.86). The cumulative survival probability from all psychoses is presented in Fig. 2. Two of the control group offspring had developed a psychotic disorder, but none of their parents had any psychiatric diagnoses.

Fig. 2 Kaplan–Meier cumulative survival probability for any psychosis developing in the offspring in the high-risk and control groups. —, controls; – – –, offspring of mothers with schizoaffective disorder; - - -, offspring of mothers with schizophrenia; ·······, offspring of mothers with other schizophrenia-spectrum disorders.

Non-psychotic mood disorders (OR=3.40, 95% CI 1.22–9.49) and hospital-treated alcohol or other substance abuse and dependence (OR=4.27, 95% CI 1.40–13.05) were more common among the high-risk offspring than among controls (see Table 4). In logistic regression analysis, mother's substance abuse was not related to her offspring's risk of substance abuse (OR=0.86, 95% CI 0.18–4.16), but paternal substance abuse increased the offspring's risk of hospital-treated alcohol or other substance abuse or dependence (OR=6.31, 95% CI 1.63–24.5). There was no interaction between maternal and paternal alcohol or other substance abuse or dependence.

DISCUSSION

Schizophrenia and psychotic disorders

We found an increased cumulative incidence of any psychotic disorder, schizophrenia and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders among the offspring of mothers with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorders and other schizophrenia-spectrum disorders compared with controls, and the cumulative incidences of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders were comparable among these three offspring groups. The cumulative incidence of schizophrenia among the offspring of mothers with schizophrenia in our study is slightly lower than in most previous high-risk studies. Our cumulative incidence was 6.7%, compared with 16.2% in the Copenhagen High-Risk Study (Reference Parnas, Cannon and JacobsenParnas et al, 1993), 13.1% in the New York High-Risk Project (Reference Erlenmeyer-Kimling, Rock and RobertsErlenmeyer-Kimling et al, 1997), 8.0% in the Israeli High-Risk Study (Reference Ingraham, Kugelmass and FrenkelIngraham et al, 1995) and 8.3% in the New York Infant Study (Reference FishFish, 1987). In the Swedish High-Risk Project the cumulative incidence of schizophrenia was only 3.6%, but the offspring had only reached the age of 22 years (Reference Schubert and McNeilSchubert & McNeil, 2003).

Several factors might have caused the lower incidence in our study. We had only one family in which both parents had schizophrenia, whereas in the New York and Copenhagen studies this especially high-risk group was considerably larger (Reference Erlenmeyer-Kimling, Marcuse and CornblattErlenmeyer-Kimling et al, 1984; Reference ParnasParnas, 1985). However, it is also possible that the high prevalences observed in the New York and Copenhagen studies were partly due to their case selection methods. Since the follow-up period in the Copenhagen study was also slightly longer than ours (up to 34–48 years of age), the late-onset schizophrenia cases would have raised our cumulative incidences only slightly. In addition, the incidence of schizophrenia in Finland, as well as in Denmark, was higher for the cohorts in the 1950s than in the 1960s, when the offspring in our cohort were born (Reference Munk-Jorgensen and MortensenMunk-Jorgensen & Mortensen, 1992; Reference Suvisaari, Haukka and TanskanenSuvisaari et al, 1999). Thus, the offspring in the Copenhagen study were born during a period (1942–1952) when the incidence of schizophrenia in the general population was higher than it was in the 1960s. Finally, we were able to diagnose only hospital-treated cases and could not interview the individuals.

Our findings are similar to those from family and adoption studies. Numerous family studies have found a morbid risk of schizophrenia among first-degree relatives ranging from 1.4% to 6.5% (Reference Kendler and DiehlKendler & Diehl, 1993). The prevalence of schizophrenia among adoptees having a biological mother with schizophrenia was 5.1% in the Finnish Adoptive Family Study and 5.7% in the Danish Adoption Study (Reference Kendler and GruenbergKendler & Gruenberg, 1984; Reference Tienari, Wynne and LäksyTienari et al, 2003). A large, Danish population-based study found that having a mother with schizophrenia was associated with a seven-fold increase in risk of developing schizophrenia (Reference Pedersen and MortensenPedersen & Mortensen, 2001); however, that study, like ours, was based on a hospital discharge register that, until recently, recorded only those treated as in-patients.

In our study, the risk of developing schizophrenia or schizophrenia-spectrum disorder was approximately equal in the high-risk groups with maternal schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. This finding is in accordance with the Irish Ros-common Family Study, in which the risks of schizophrenia and of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders were approximately equal among the relatives of probands with schizophrenia, schizotypal personality disorder, schizoaffective disorder or other non-affective psychotic disorders (Reference Kendler, McGuire and GruenbergKendler et al, 1993b ).

Other Axis I disorders

Apart from bipolar disorder, the cumulative incidences of hospital-treated mental disorders among the offspring of mothers with affective disorders were low and similar to those in the control group, whereas in the New York study, cumulative incidences of schizophrenia-related psychotic disorders, schizoaffective disorders and non-psychotic and psychotic affective disorders were all increased among the offspring in the high-risk group compared with controls (Reference Erlenmeyer-Kimling, Rock and RobertsErlenmeyer-Kimling et al, 1997). It is likely that the cumulative incidences of less severe disorders in our study would have been higher if we had interviewed the offspring.

The cumulative incidence of hospital-treated non-psychotic mood disorders was increased among high-risk offspring, consistent with the findings from the Swedish (Reference Schubert and McNeilSchubert & McNeil, 2003) and Israeli (Reference Ingraham, Kugelmass and FrenkelIngraham et al, 1995) high-risk studies. We also found increased rates of hospital-treated alcohol and other substance abuse or dependence among high-risk mothers, fathers and offspring, compared with controls. In the Copenhagen and Swedish high-risk studies, alcohol or other substance abuse was more common among the high-risk than control offspring (Reference Parnas, Cannon and JacobsenParnas et al, 1993; Reference Schubert and McNeilSchubert & McNeil, 2003), whereas there was no significant difference between the high-risk and control groups in the New York study (Reference Erlenmeyer-Kimling, Rock and RobertsErlenmeyer-Kimling et al, 1997). In our study, the cumulative incidences of substance use disorders are based on hospital records only and reflect severe, hospital-treated forms of the disorders. Interestingly, we found that paternal, but not maternal, substance abuse increased the offspring's risk of substance abuse. This might have been partly caused by the fact that paternal substance use disorders were severe and had usually been the cause of hospitalisation, whereas maternal substance use disorders were rarely severe enough to be the primary cause of hospitalisation. Consistent with our study, the occurrence of alcoholism and/or anti-social personality disorder in the Copenhagen Study was higher among fathers in the high-risk group compared with the control group (27% v. 17%; Reference ParnasParnas, 1985).

Limitations

We were not able to interview the study participants, which was clearly a limitation. However, the average duration of treatment contact was long: 23.0 years for the mothers, 9.0 years for the fathers and 11.4 years for the offspring. Thus, the case records usually spanned several years and were quite detailed. We also assessed all available information, for example the notes made by nurses and psychologists, not just the notes made by the treating psychiatrist. It is reasonable to assume that the prevalence of psychotic disorders is accurate: in a Finnish health survey of 8000 persons, 99% of those with a psychotic disorder had received psychiatric treatment (Reference Lehtinen, Joukamaa and JyrkinenLehtinen et al, 1991). Of the 73 individuals who had developed schizophrenia by 1994 in the North Finland 1996 Birth Cohort, only two had been treated as out-patients only (Reference Isohanni, Mäkikyrö and MoringIsohanni et al, 1997). In contrast, in the Copenhagen Study, only two-thirds of the high-risk offspring who developed schizophrenia had had hospital treatment (Reference Parnas, Cannon and JacobsenParnas et al, 1993). Because case notes included data on family history, the raters could not always remain masked to whether the child belonged to the high-risk or control group. However, they were masked to the actual parent–child pairs, and thus the parental diagnoses did not affect the diagnostic assignment of offspring.

The accuracy of data on psychiatric diagnoses in the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register is excellent: in 1986, the diagnoses in the register and in the hospital case notes were identical in 99% of cases of schizophrenia and in 98% of all mental disorders. The reliability of schizophrenia diagnoses in the Hospital Discharge Register has been assessed in several studies, which showed that Finnish psychiatrists tend to apply a narrow definition of schizophrenia in clinical practice and that the register diagnosis of schizophrenia is reasonably reliable (Reference Suvisaari, Haukka and TanskanenSuvisaari et al, 1999).

We excluded mothers for whom we could not assign a diagnosis because of inadequate information. This group included both women with severe psychotic disorders who had died before 1976 and whose case notes had therefore been destroyed, and women with less severe forms of the disorder who had had short hospital treatments only and thereby insufficient case-note information to assign diagnoses. Among the offspring of mothers with diagnoses deferred, one had psychotic disorder NOS and another had a hospital diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder, but the case notes were missing. Thus, the cumulative incidence of any psychotic disorder among the offspring of mothers with diagnoses deferred was 8.3%, and the exclusion of these cases from the high-risk group did not have a major effect on the cumulative incidences of psychotic disorders in the group.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ The cumulative incidences of schizophrenia and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders among the offspring of women with these disorders were in the same range as those in first-degree relatives of probands with schizophrenia and adoptees having a biological mother with schizophrenia, but were lower than those found in most previous high-risk studies.

-

▪ The children of mothers with schizophrenia are also at increased risk of developing non-psychotic disorders, particularly affective and substance use disorders.

-

▪ Psychiatric disorders, particularly alcohol and substance use disorders, were more common in fathers in the high-risk group, which may further increase the risk of mental disorders among their offspring. Paternal, but not maternal, alcohol and substance use disorders increased the risk of such disorders among the offspring.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Our case ascertainment was mainly based on the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register. Less severe disorders that did not require hospitalisation remained undetected.

-

▪ Structured psychiatric interviews were not conducted.

-

▪ Although the quality of case-note data was generally excellent, for some individuals information was too scarce for the assignment of a diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by a grant from the Stanley Medical Research Institute. L.T.N. was supported by the Finnish Foundation for Psychiatric Research and the Finnish Psychiatric Association, and J.M.S. by the Finnish Cultural Foundation. The authors thank Professor Matti Huttunen and Professor Sarnoff Mednick for their contribution regarding the original study sample, Ms. Sanna Hannuksela and Ms Kirsi Niinistö for their assistance with the follow-up data collection and recording, and DrTimo Partonen for helpful comments on the manuscript.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.