Depression and anxiety, place a significant burden on health services. In 2011/2012 the cost of prescribed antidepressant medication in Scotland was £31.4 million.1 Mood disorders were also the most prevalent psychiatric hospital discharge diagnosis in women in Scotland in 2012.2 Depression can be treated effectively within primary care.3 However, fewer than 50% of patients receive treatment.Reference Kohn, Saxena, Levav and Saraceno4 This treatment gap may be because of non-presentation as a result of fear of stigma or uncertainty about treatment options.Reference Kohn, Saxena, Levav and Saraceno4 A community setting, where voluntary organisations and self-help groups provide local support networks, may be more appealing.Reference Jorm, Jorm, Korten, Jacomb, Christensen and Rodgers5 Interventions that undertake community-based promotion, recruitment and delivery, may therefore have the potential to engage people who would otherwise not present to the health service.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) as a treatment option for mild to moderate depression.6 High-intensity forms of CBT delivered by a mental health expert are recommended to treat moderate and severe levels of depression.Reference Wiles, Thomas, Abel, Ridgway, Turner and Campbell7 This approach is therapist-intensive and access for patients can be limited because of long waiting lists.6 Consequently, delivery systems are changing, for example with increasing proportions of patients offered low-intensity delivery as a first step in the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme in England. Low-intensity forms of CBT include written self-help books, computerised CBT and self-help groups.Reference Lewinsohn, Antonuccio, Steinmetz and Teri8–Reference Cuijpers, Donker, van Straten, Li and Andersson11 Although less therapist-intensive, individual support is still provided via phone or face-to-face by workers such as self-help coaches or psychological well-being practitioners.Reference Gellatly, Bower, Hennessy, Richards, Gilbody and Lovell12 A limited number of low-intensity community interventions have been previously assessed in randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Previous studies either assessed the effect of a single one-off classReference Fennel13 or focused on stress/anxiety.Reference White14 NICE found no low-intensity CBT classes addressing depression and also no associated health economic outcomes.6 This study attempts to address the research gap by being the first intervention to explore low-intensity CBT classes for low mood and stress guided by self-help resources delivered in a community setting.

The Living Life to the Full (LLTTF)Reference Williams15 classes consist of eight, weekly, 1.5 h sessions in a classroom where participants with depression and anxiety are guided through a CBT-based life-skills course by trained class leaders. A pilot RCTReference McClay, Collins, Matthews, Haig, McConnachie and Morrison16 demonstrated effective recruitment and adherence, and found improved levels of anxiety and depression 3 months after randomisation. The aims were to compare the effectiveness of a community-based CBT self-help group intervention in improving symptoms of depression, anxiety and social function at 6 months. The primary research question was: does immediate access to the LLTTF classes result in an improvement in symptoms of depression at 6 months compared with a delayed access control group? Secondary questions were (a) does immediate access to the LLTTF classes result in an improvement in anxiety and social function at 6 months, compared with delayed access; (b) is the intervention cost-effective; and (c) is the intervention satisfactory to participants?

Method

Study design and participants

The study used an individually randomised design with delayed access control. Community recruitment methods included newspaper advertisements and assistance from the Scottish depression charity Action on Depression. A series of Metro (free newspaper) advertisements were placed during two, 6-week recruitment periods between August 2012 and February 2013 (four advertisements per week plus online advertising and occasional feature-sized advertisements making up approximately quarter of a page in the classified advertisement area of the paper). Advertisements included the following text:

‘Living Life to the Full. Living Life to the Full Project – I can't be bothered. What's the point? I don't enjoy doing that anymore. I am fed up. Does this sound like you? If so, you may be suffering from low mood. These are very common problems and with help, can be greatly improved. If you would like to attend relaxed, friendly, local life skills classes that aim to help you get your spark back, contact (name) on (phone no.), or email (university email address). We provide the tea and biscuits!’

The charitable organisation Action on Depression advertised the study via their website, phone support line, newsletters and local groups. Participants included individuals who were, and were not, currently receiving National Health Service (NHS) help for their symptoms of depression and anxiety throughout Central Scotland. Data were collected and stored at the University of Glasgow. The study commenced in July 2012, recruitment began in August 2012 with the final data analysis being completed in January 2014. Ethical approval was granted by the College of Medical, Veterinary & Life Sciences Ethics Committee for Non Clinical Research Involving Human Subjects, University of Glasgow (Ref. 2012065) and in line with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study is registered with Current Controlled Trials (ISRCTN86292664).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: aged 16 years of age or older with at least mild depressive symptoms, defined as a score ≥5 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).Reference Spitzer, Kroenke and Williams17 Exclusion criteria were: currently receiving psychotherapy/talking therapy or counselling; unable to read, speak or understand English; unable to travel to classes; no consent to abide by normal social etiquette within the classes. With the aim of being inclusive in this community-based trial, we minimised exclusion criteria. No upper cut-off for depression score was used in line with our previous work. This approach was successfully employed in the pilot studyReference McClay, Collins, Matthews, Haig, McConnachie and Morrison16 and suited the inclusive pragmatic delivery using voluntary sector staff. This approach is unusual in low-intensity settings, however, it is in line with NICE low-intensity guidelines that emphasise complexity rather than severity of depression alone.6

Community-based recruitment has sometimes been criticised because of a concern that participants may not satisfy the criteria for clinical depressionReference Andersson and Cuijpers18 and therefore do not reflect the sorts of people attending clinical services. Participants were therefore asked to complete a Mini International Psychiatric Interview (MINI, Version 6.0)Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller19 via telephone with a research assistant to better describe the recruited sample in terms of their past, present or recurring depression.

Randomisation

When sufficient participants to fill at least two classes had undergone baseline assessments, the statistician performing the randomisation was sent a file containing study ID, plus the minimisation factors of preferred time (afternoon or evening) and location (Glasgow or Edinburgh) of class, and PHQ-9 score (≤9, ≥10). No other information (e.g. age, gender) was included. A computer program was then written to randomly assign individuals to the immediate access (IA) group or delayed access control (DAC) group in equal numbers (or as close as possible, if there was an odd number of individuals being assigned). After assigning all individuals, the program checked whether the treatment balance for each time/location subgroup, and for each PHQ-9 subgroup, was as close to equal as possible (i.e. equal, or out by one). If not, the process was started again, and repeated until an assignment was reached that resulted in minimal imbalance between treatment groups in relation to each minimisation factor. This was first carried out in October 2012, once the first wave of participants had completed their baseline assessments. In March 2013, a second wave of participants was recruited. The above process was repeated, with the modification that when a random allocation of this second wave was attempted, the treatment group imbalance was assessed in relation to all study participants (including those randomised in October 2012), in order that the final study treatment groups were well balanced in relation to the minimisation factors over the entire study population.

All computer programs and treatment allocation files were stored in a restricted area of the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics network, with access only for the study statisticians. Analyses were carried out by junior staff in accordance with the study protocol, and results were reviewed by senior statistical and health economic staff prior to dissemination. The IA group began attending classes within 2–3 weeks of randomisation. The DAC group were advised to continue usual management of their symptoms and began attending classes after a delay of 6 months.

Masking

The Robertson Centre for Biostatistics, where the analyses were carried out, is part of the UKCRC-registered Glasgow Clinical Trials Unit. For regulatory clinical trials and other major randomised studies, treatment group allocations are routinely masked from the statisticians, until database lock. This study was an academic trial with a small budget, so could not be carried out with the same level of restrictions. The statistician carrying out the analysis had access to randomisation codes throughout the analysis. Nevertheless, the analyses were carried out in accordance with the statistical section of the study protocol and the original funding application, which were written prior to the trial. The researchers were necessarily not masked, since they had to arrange the LLTTF classes with study participants. Randomisation took place in two blocks, with the first 104 participants randomised in October 2012, and the remaining 38 randomised in March 2013. On each occasion, all baseline data was collected prior to randomisation being carried out, ensuring that neither participants nor researchers could anticipate which group an individual would be assigned to at the point of baseline data collection. At follow-up, data was collected via online participant self-completed questionnaires, without direct contact with study researchers. The final study database, with randomised group allocations, was provided to the study statistician for analysis, which was carried out according to the plan specified in the study protocol paper.

Intervention: the LLTTF classes

LLTTF classes were delivered by the charitable organisation Action on Depression and involved eight, weekly classes that taught a range of CBT-based life skills. Classes were 90 min long, attended by up to 16 participants and were conducted in a classroom setting based in a locally accessible location for example a library. Two experienced, trained class leaders from Action on Depression, used pre-prepared locked slides and support notes/scripts. Trainers were all Action on Depression volunteers from varying backgrounds including the general public, a psychology assistant, a nurse, and Action on Depression staff members. All had experience of mental health presentations and support, and in each training pair at least one was an experienced facilitator who had delivered the classes before.

Each weekly class focused on a different common problem faced by people when they feel low or anxious, with content produced by a trained and qualified CBT practitioner and covering key CBT content.6, Reference Ridgway and Williams9, Reference McClay, Collins, Matthews, Haig, McConnachie and Morrison16 The class content is: 1: Why do I feel so bad? (self-formulation/CBT model), 2: I can't be bothered doing anything (behavioural activation), 3. Why does everything always go wrong? (identifying and changing negative automatic thoughts), 4: I'm not good enough: (low confidence), 5: How to fix almost everything (problem-solving strategies), 6: The things you do that mess you up (reducing safety behaviours), 7: Are you strong enough to keep your temper? (anger and irritability) and 8: 10 things you can do to help you feel happier straight away (healthy living, a reminder of core principles in the course). A ninth session, planning for the future and reunion, addressing relapse prevention is held 6 weeks after the final class. As seen in the session names, the classes use everyday language and avoid professional terminology in order to make the intervention accessible to all while covering key CBT topics such as altered thinking, behavioural activation, problem-solving and relapse prevention. This way of communicating CBT is highly accessibleReference Martinez, Whitfield, Drafters and Williams20 and shown to be helpful in previous trials.Reference Sharpe, Walker, Williams, Stone, Cavanagh and Murray21, Reference Grover, Naumann, Mohammad-Dar, Glennon, Ringwood and Eisler22 They are designed to encourage an individualised plan to be made at the end of each session using a ‘plan, do, review’ structure;Reference Williams and Chellingsworth23 there are currently no equivalent classes using the same model of delivery. Fidelity of class delivery was assessed by the lead research assistant and an independent research volunteer. Two consistency checks per 8-week course were carried out using a consistency check-list for adherence to class content and quality of delivery.

Measures

The primary outcome was level of depression at 6 months assessed by the PHQ-9. Secondary measures included the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7),Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe24 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)Reference Zigmond and Snaith25 and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS).Reference Mundt, Marks, Shear and Greist26 In addition, satisfaction was recorded using the client satisfaction questionnaire (CSQ-8).Reference Nguyen, Attkisson and Stegner27 The CSQ-8 is an 8-item questionnaire rated using a 4-point Likert scale. Scores range from 8 to 32 with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction with the intervention in question.

Statistical methods

Outcome measures were compared between study groups on an intention-to-treat basis using linear regression models adjusting for baseline values of the outcome and age, gender, duration of symptoms, use of antidepressants and randomisation stratification variables (time/location of class, PHQ-9 ≤9/≥10 at baseline). We also reported the primary outcome in terms of the proportion of participants scoring nine or less on the PHQ-9 (reflecting mild depression), the number of people dropping five points or more on the PHQ-9 (reflecting category improvement and this is seen as an ‘adequate’ improvement), and the proportion of participants whose PHQ-9 score dropped by 50% or more between baseline and 6 months (as widely used in IAPT and many clinical services). Subgroup analyses were carried out to test for interactions between study group and baseline PHQ-9 (≤9/≥10), age, gender, duration of symptoms and antidepressant use at baseline. All analyses were carried out using R for Windows 3.0.2.28 P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Statistical power and sample size

A criticism sometimes made of studies using self-referral and community-based recruitment is that participants are not significantly depressed. We therefore powered the study to detect a clinically significant difference of 5.5 pointsReference McMillan, Gilbody and Richards29 on the PHQ-9 within the subgroup of participants with more severe depression (PHQ-9 ≥10) at baseline. Our pilot studyReference Spitzer, Kroenke and Williams17 showed that for those with a PHQ-9 ≥10 at baseline, the standard deviation of changes in PHQ-9 scores was 6.1. Based on a two-sample t-test, a sample size of 54 participants would be required for 90% power. In the pilot, follow-up data was available for 65% of participants, so we needed to randomise 84 participants with PHQ-9 scores ≥10. We expected one third of participants to have PHQ-9 <10 at baseline, so we aimed to randomise 126 participants in total. Our trial design has been reported in a protocol publication.Reference McClay, Morrison, McConnachie and Williams30

Economic analysis

Economic analysis was performed from a health service perspective as recommended by NICE.31 The Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI)Reference Beecham, Knapp, Thornicroft, Brewin and Wing32 and EQ5D33 were used to measure participants’ use of health services and current state of health. Health service costs were calculated from self-report in the CSRI over 6 months. The costs used were obtained from Unit Costs of Health and Social Care (2015). Generalised linear models with the log link function were applied to model costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) in relation to study group. The method of recycled predictions was used to estimate the differences in costs and QALYs between randomised groups, using 10 000 bootstrapped data-sets, stratified by randomised group. These estimates were plotted on the cost-effectiveness plane. Interpretation was aided using cost-effectiveness acceptability curves derived using the net-benefit approach with values between £0 and £10 000 placed on a QALY gain to include the threshold used by NICE.Reference Glick, Doshi, Sonnad and Polsky34

Results

Participant characteristics

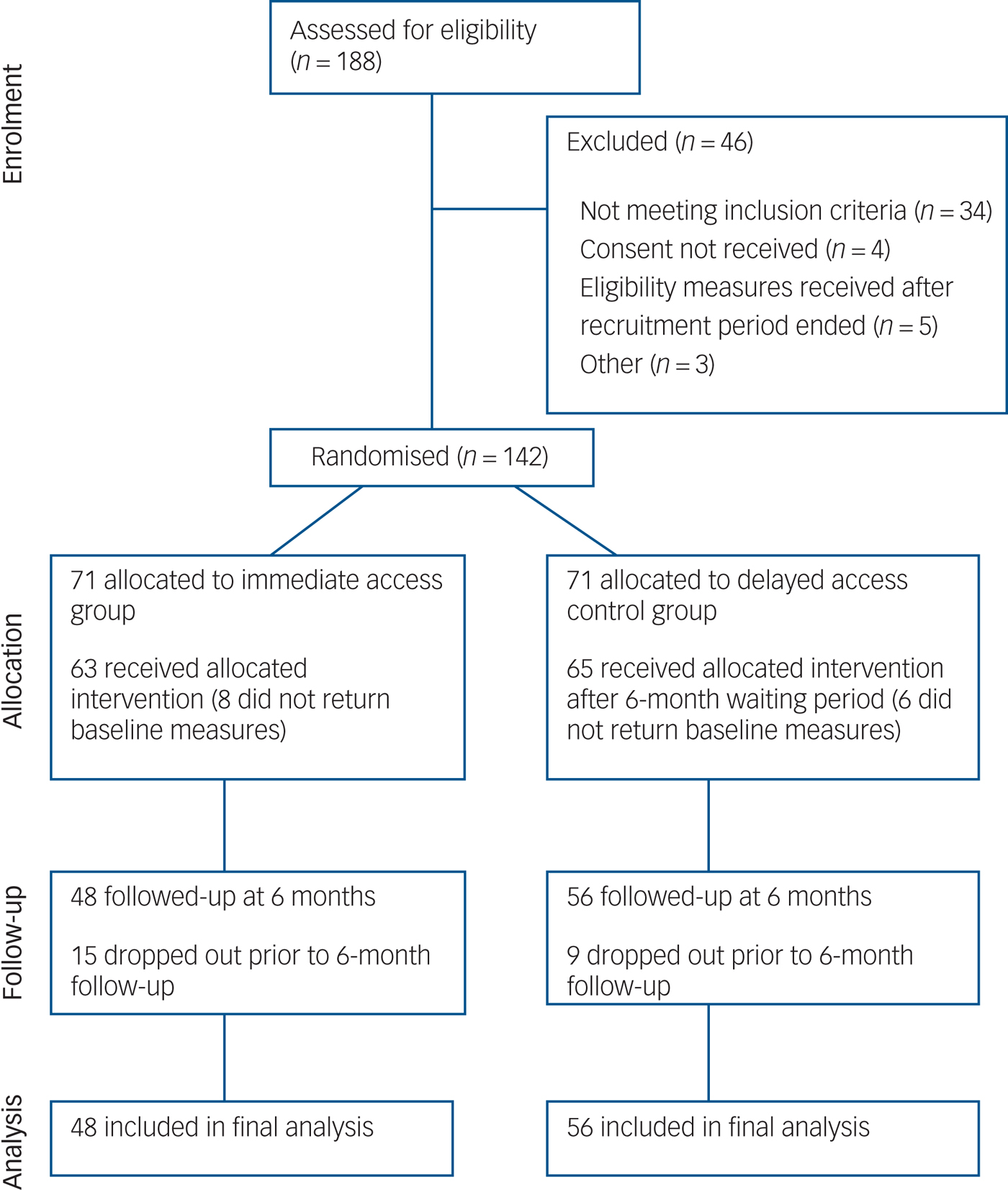

Figure 1 presents a CONSORT diagram. The required number of participants scoring ≥10 on the PHQ-9 entered the study before ending recruitment. Demographic data at randomisation are presented in Table 1 (additional data is available in supplementary Table DS1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2017.18). Baseline measures are presented in Table 2. At 6 months 73.2% (n = 104 of 142) were followed up. No noticeable differences in demographic data were found between the IA and DAC groups at baseline, or in rates of drop-out at 6 months. There were also no significant differences in age (P = 0.97), gender (P = 0.63), chronicity (P = 0.33) or PHQ severity at eligibility (P = 0.21) between those who completed the study and those who did not (i.e. those providing 6-month follow-up data v. those who dropped out). All measures (apart from the MINI) were completed at baseline and 6 months in order to maximise the response rate at the primary outcome (6 months) and to avoid participant burden with repeated questionnaires. No further measures were taken after the delayed group received their intervention, a requirement of the funders.

Fig. 1 CONSORT diagram of participant flow through the intervention.

Table 1 Characteristics of participants at randomisationa

a. See supplementary Table DS1 for the data relating to education and ethnicity.

b. Data for the Mini International Psychiatric Interview (MINI) was only available as follows: overall n = 93; immediate access (IA) group, n = 41; delayed access control (DAC) group, n = 52.

c. For chronicity of symptoms there is missing data for one individual in the DAC group.

Table 2 Main outcome measures for both groups at baseline and 6-month follow-up

1 Moderately-severe depression;

2 Mild depression;

3 Moderate depression;

4 Moderate anxiety;

5 Mild anxiety;

6 Borderline depression/anxiety;

7 Depression/anxiety;

8 No depression/anxiety;

9 Moderately-severe psychopathology;

10 Moderate psychopathology.

Main outcomes

The percentage of participants reducing their PHQ-9 score between baseline and 6 months by 50% or more was 17.9 (n = 10, DAC group), and 43.8 (n = 21, IA group) (P = 0.008). The percentage of participants reducing their PHQ-9 score by five or more points (representing a clinically meaningful shift in severity category) was 30.4% (n = 17, DAC group) v. 56.2% (n = 27, IA group) (P = 0.014). The percentage of participants scoring nine or lower at follow-up was 62.5% (n = 30, IA group) compared with 32.1% (n = 18, DAC group) (P = 0.004); at baseline this was 17.5% (n = 11) and 15.4 (n = 10) for the IA and DAC groups, respectively (P = 0.938).

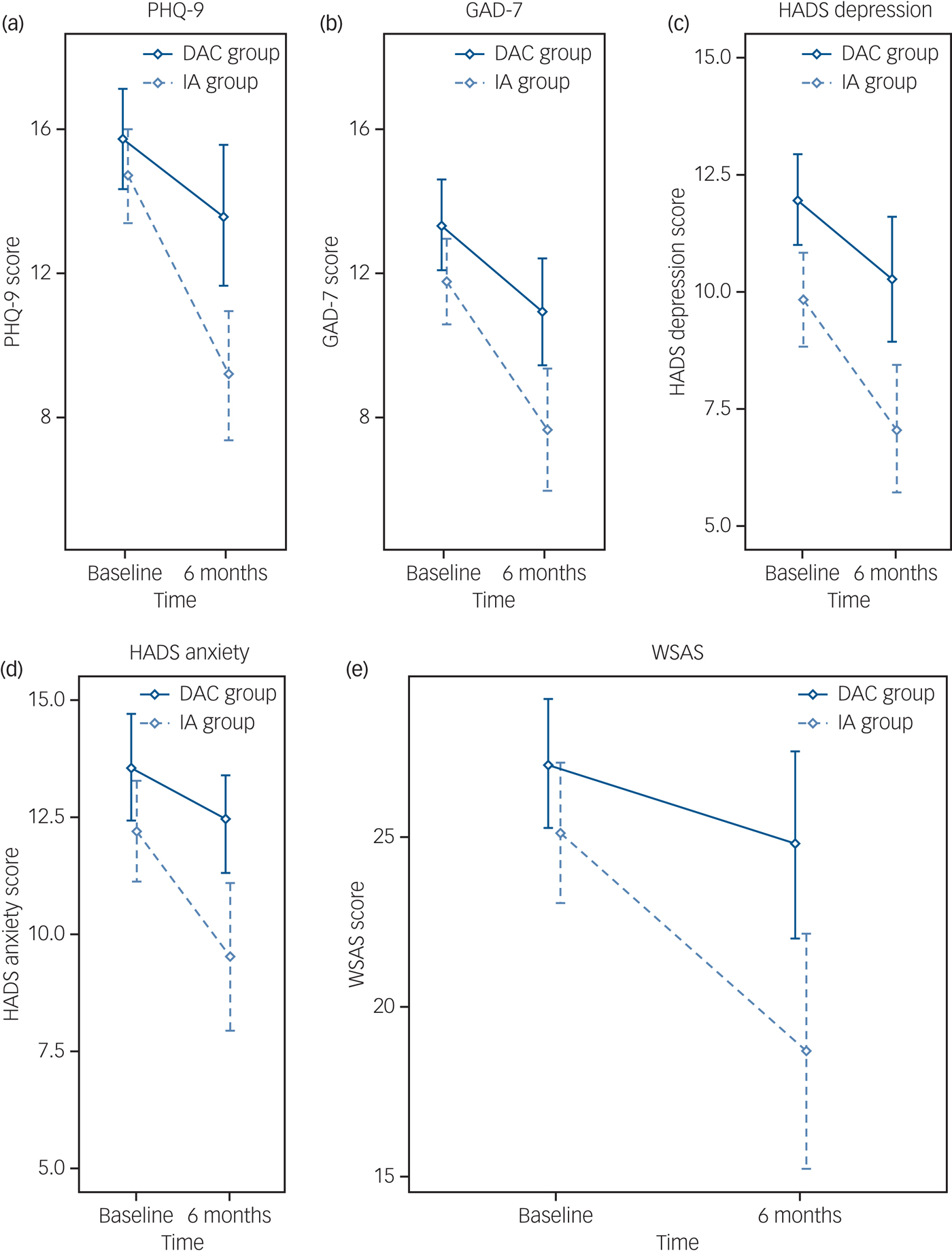

Table 3 and Fig. 2 present further outcome measures for PHQ-9, GAD-7, HADS-D, HADS-A and WSAS at baseline and 6-month follow-up. A significant difference in favour of the IA group was observed for PHQ-9 (–3.64, 95% CI –6.06 to –1.23, P = 0.004) and GAD-7 (–2.83, 95% CI –5.03 to –0.64, P = 0.012). Additional measures of depression and anxiety (HADS) also significantly improved at 6 months in the IA group compared with the DAC group. Social function as measured by WSAS at 6 months was improved in favour of the IA group (–5.31, 95% CI –9.35 to –1.27, P = 0.011).

Fig. 2 Means and 95% confidence intervals of scores on the different measures for both groups at baseline and 6-month follow-up.

(a) Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), (b) Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), (c) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) depression, (d) HADS anxiety and (e) Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WASAS).

Table 3 Between-group differences from baseline to 6-month follow-upa

a. Adjusted for baseline scores, age, gender, medication use and chronicity.

A significant treatment effect was observed for participants with a baseline PHQ-9 ≥10 (n = 86) (–5.37, 95% CI –8.33 to –2.42, P < 0.001), whereas those with baseline PHQ-9 ≤9 (n = 18) showed no change at follow-up (1.15, 95% CI –3.33 to 5.62, P = 0.591) (P-value for interaction, 0.045). No significant interactions were observed with respect to age, gender, duration of symptoms or antidepressant use at baseline. In relation to deterioration, defined as any increase in PHQ-9 score at 6 months compared with baseline, the difference between groups did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.07). However, there is a trend towards greater deterioration in the DAC group as in the IA group 8 of 48 deteriorated (16.7%) whereas 19 of 56 (33.9%) in the DAC group showed an increase in PHQ-9 score at the follow-up point. It is possible that the study is not adequately powered for the deterioration analysis.

Cost-effectiveness

Total NHS treatment costs in the 6 months prior to LLTTF were £907 and £802 for the IA and DAC group, respectively, and reduced during the 6-month intervention to £780 and £740, respectively. The probabilities of a net benefit at willingness to pay thresholds of £20 000, £25 000 or £30 000 was 0.928, 0.944 and 0.955, respectively (supplementary Fig. DS1). The net result was improved outcomes and high satisfaction in the intervention group at a similar cost to not delivering the classes (supplementary Fig. DS2).

Given that the classes have a fixed cost, then if the intervention has no effect on health service utilisation, we would expect there to be a difference in cost between the intervention and control groups. In order to estimate the mean difference in costs between groups, we fitted a regression model. For this model to be valid, we must adjust for the stratification variables (location/time and baseline PHQ-9 category), regardless of their significance in the model.

The P-value of 0.998 for the intervention effect estimate means that there is no evidence of a difference in the mean cost between the two groups. The point estimate for the intervention effect is close to null, suggesting that the cost of the intervention may be offset by a reduction in health service utilisation. However, the confidence interval for the relative cost difference is wide (roughly 60% either way), and from the recycled predictions, the confidence interval for the difference in mean costs between groups is approximately –£400 to +£500; these both indicate a high degree of uncertainty. Similarly, there is no evidence of a difference in QALYs between groups, but in this case the trend is towards a benefit in the intervention group.

Taken together, these data suggest that the intervention may be resulting in a reduction in health service utilisation and an improvement in quality of life, which would be consistent with the improvements in symptoms observed in the study. However, probably because of the high variability in these measures, we cannot estimate the between-group differences with very much precision. In order to obtain definitive answers in terms of the cost-effectiveness of the intervention, we suggest that further research is required, with a larger sample size, in order to narrow these confidence intervals.

Attendance, participant satisfaction and protocol fidelity

In the IA group 32.4% (n = 23 of 71) failed to attend classes and dropped out of the research study. Reasons for drop-out included: alternative treatment (n = 5); lack of time (n = 4); deteriorating mood (n = 3); moved house (n = 1); and no reason given (n = 12). Of the remaining participants, 89.5% (n = 43) attended at least one of the LLTTF classes; 75% (n = 36) attended ≥4 sessions, with 33.3% (n = 16) attending all eight sessions (supplementary Fig. DS3). Mean participant satisfaction with the LLTTF classes (IA group) was high with a CSQ-8Reference Nguyen, Attkisson and Stegner27 score of 24.3 (s.d. = 5.1) (n = 47). Participant satisfaction with the classes increased as their symptoms of depression, anxiety and social function improved. Classes were rated as useful, quite useful or extremely useful by 81.8% of IA participants who returned class feedback forms (n = 36 of 44). In total, 17 LLTTF classes were monitored for protocol fidelity. All sessions were rated as competently delivered with a mean consistency checklist score of 8.8 (s.d. = 1.1) and a mean class leader presentation score of 9.6 (s.d. = 1.1) from a maximum score of 10.

Discussion

Community recruitment

Our recruitment methods reached individuals in the community in need of support i.e. people with diagnostic depression, anxiety and impaired social function (Table 1), with chronic symptoms of >5 years, but with 49.3% not currently on prescribed medication and only 46.5% currently attending their general practitioner (GP) (Table 1). This is in line with previous research that suggests that less than 50% of individuals with depression in communities seek help from their GP.Reference Kohn, Saxena, Levav and Saraceno4 Our recruitment approach did not exclude people with higher levels of depression – in line with our previous work.Reference Spitzer, Kroenke and Williams17, Reference Williams, Wilson, Morrison, McMahon, Walker and Allan35 This approach tends to differ from that taken in many NHS services such as IAPT in England that often exclude people from low-intensity therapies. However, recent work by Farrand & Woodford,Reference Farrand and Woodford36 suggest that those with higher depression scores can benefit from using low-intensity approaches.

When compared with a recently published trial of CBT delivered in a primary care setting, our recruitment methods reached a greater proportion of individuals who were unmarried (49.3% v. 19.0%;Reference Wiles, Thomas, Abel, Ridgway, Turner and Campbell7 35% of Scottish adults are unmarried), had chronic symptoms of depression >2 years (80.9% v. 59.0%), and were black and minority ethnic (8.5% v. 2.0%; 3.3% of the Scottish population are black and minority ethnic).37 Although men were underrepresented in the study (32.4% were male compared with 48% in the population), the sample was representative of the Scottish population in relation to age. This is seen in the fact that the age range in the sample had a wide range of 20–80 years old. In addition, the mean age was 46.6 years; and the most populated age category in Scottish adults is 45–59 years.37 This fits with previous research on self-referral where community methods of recruitment engaged people who more accurately reflected the make-up of the community than those referred by GPs.Reference Brown, Boardman, Whittinger and Ashworth38 As people were recruited from the community, the findings of this research are widely applicable.

Findings in context

At the 6-month follow-up, statistically significant between-group differences were observed for all outcome measures demonstrating that the LLTTF intervention was effective in improving symptoms of depression, anxiety and social function (Table 3, Fig. 2). A clinically important response in PHQ-9 has been described variously in previous studies as: (a) a reduction of five points or more; or (b) a post-treatment score of ≤9; or (c) a minimum of 50% improvement in PHQ-9 score.Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe24 The findings for each of these measures show high recovery rates. In those scoring ten or more, the PHQ-9 reduced by 37.4% (–5.5 points) in the IA group from baseline to 6 months (14.7 v. 9.2 points; Table 2). Clinically this indicates a reduction from moderately severe to mild depression and suggests that the intervention was effective for participants with more severe depression.

Significant between-group differences were observed for social functioning, with the IA group improving their score for social function on the WSAS. An individual's ability to conduct normal social roles is an integral component of their quality of life.Reference Hirschfeld, Montgomery, Keller, Schatzberg, Moller and Healy39 Depression and anxiety have a negative effect on personal and professional relationships via loss of energy, reduced self-esteem and increased distress. Therefore the ability of the LLTTF classes to improve social functioning has the potential to have an impact on individuals’ long-term quality of life.

Intervention delivery

Participant satisfaction with LLTTF was high (mean CSQ-8 score of 24.3 (s.d. = 5.1), in line with RCTs undertaken in both primary care (25.3, s.d. = 5.8)Reference Richards, Hill, Gask, Lovell, Chew-Graham and Bower40 and out-patient settings (24.4, s.d. = 3.5).Reference Houghton and Saxon41 The charity delivering the classes is experienced in working with adults with depression and anxiety. Working alongside Action on Depression, an established and well equipped voluntary organisation, was a strength of our intervention.Reference Glasgow, Boles and Vogt42

Economic analysis

The intervention was effective in improving symptoms of depression, anxiety and social function while being cost-neutral and available at an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio below the NICE thresholds for funding. CBT delivered within specialist care can be resource intensive and waiting lists can be long. Therefore community-based group CBT interventions, such as the LLTTF classes, can provide an alternative route of management, to larger groups of patients, at no additional cost to the health service.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first RCT to explore the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of guided self-help CBT classes for depression delivered in a community setting. The study design, class-based delivery, co-working with a charity, and the community recruitment approach show high ecological validity and has the potential to be readily transferred into practice. Our recruitment strategy ensured an adequate sample size of individuals with high baseline PHQ-9 scores to allow for analysis of intervention effects on increasing severity of symptoms. No participants were recruited from an NHS setting allowing us to demonstrate the effectiveness of reaching individuals in need of support in the community. However, this study has some limitations. As with many similar studies, an issue is the choice of control group. The role of a control group is to protect internal validity.Reference Freedland, Mohr, Davidson and Schwartz43 A delayed access control achieves this, and a review of community-based researchReference Farrand and Woodford36 recommends a delayed access control design as a way of maximising recruitment and retention. An alternative would have been to have a two-arm study comparing the classes with an alternative existing class-based intervention to match any socialisation aspect across the arms. However, such a change would require far larger sample sizes, and significantly larger funding, Additionally and importantly, such an intervention is not routinely available in community settings, and does not reflect real-world experience. The current study design has the advantage of helping understand what happens to people in communities who are receiving treatment as usual. However, the design could be improved by including a longer-term follow-up (≥12 months) to examine whether the positive findings at 6 months were maintained long term would be valuable. As a small funded trial, the resources available were insufficient to support separate staff for notifying participants of their allocation group, arranging treatment classes, supporting the delivery of classes and collection of outcome data. Outcome data were collected by self-completed questionnaires, so whether or not the researchers were aware of treatment groups should have had little or no impact. Finally, it is possible that the positive effect of LLTTF may have been because of session content, availability of group-based support or a combination. Further exploration of long-term maintenance and a better understanding of process issues are therefore required.

Implications

The LLTTF intervention demonstrates that low-intensity CBT classes delivered within a community setting are effective and cost-effective in the management of depression, anxiety and impaired social function, and can provide an alternative treatment option for use in primary care and community settings. Community-based recruitment can successfully reach individuals in need of support and may provide an alternative route of help for people not engaging with the health service, with only about 45% of participants seeing their GP for support. Community-based interventions are a promising addition to mental healthcare provision and warrant further investigation.

Funding

The RCT was funded by the Chief Scientist Office (CSO, Ref. CSO CZH 4 738), a section of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates (Ref. CZH 4 738). The CSO and its reviewers gave valuable comments regarding the study protocol. The project was sponsored by the University of Glasgow and was carried out in the Institute of Health and Wellbeing.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Action on Depression in delivering the intervention; the class facilitators; and research volunteer Stuart Rae.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2017.18

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.