Social anxiety disorder (SAD), characterised by excessive fear of being negatively evaluated or scrutinised in social situations, is among the most common anxiety disorders with a lifetime prevalence exceeding 10%. 1,Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2 Without treatment, the condition is considered chronic, imposing great individual suffering and costs for society. Reference Fehm, Pelissolo, Furmark and Wittchen3 Standard treatment options for SAD include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) and cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT). Reference Baldwin, Anderson, Nutt, Allgulander, Bandelow and den Boer4,5 Several randomised controlled trials have shown that CBT for SAD can successfully be delivered via the internet (ICBT), Reference Furmark, Carlbring, Hedman, Sonnenstein, Clevberger and Bohman6–Reference Berger, Hohl and Caspar9 with effects comparable to face-to-face CBT. Reference Andersson, Cuijpers, Carlbring, Riper and Hedman10 Even though SSRIs and CBT/ICBT are effective treatments for SAD, Reference Bandelow, Reitt, Röver, Michaelis, Görlich and Wedekind11 a substantial proportion of patients relapse or do not respond to monotherapy and combining the treatments is therefore common in the clinic. 5,Reference Blomhoff, Haug, Hellström, Holme, Humble and Madsbu12 Studies assessing the added benefit of adjuvant therapy for SAD, however, are scarce and findings are mixed, Reference Blomhoff, Haug, Hellström, Holme, Humble and Madsbu12–Reference Walkup, Albano, Piacentini, Birmaher, Compton and Sherrill14 although recent meta-analytic work suggests added value of combined treatment in affective disorders. Reference Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Koole, Andersson, Beekman and Reynolds15 Also, experimental research in animals Reference Karpova, Pickenhagen, Lindholm, Tiraboschi, Kulesskaya and Ágústsdóttir16 and humans Reference Bui, Orr, Jacoby, Keshaviah, LeBlanc and Milad17 has suggested beneficial effects of SSRIs on extinction learning, i.e. the laboratory analogue to exposure-based therapy.

Neuroimaging activation studies of patients with SAD during emotional challenges, such as public speaking and emotional face-processing tasks, have revealed amygdala hyperactivity Reference Brühl, Delsignore, Komossa and Weidt18,Reference Phan, Fitzgerald, Nathan and Tancer19 and a relationship between amygdala reactivity and clinical symptoms. Reference Phan, Fitzgerald, Nathan and Tancer19,Reference Goldin, Manber, Hakimi, Canli and Gross20 Decreased neural reactivity after treatment of SAD either with SSRIs or CBT have been reported for several brain regions, although most consistently for the amygdala, Reference Faria, Appel, Åhs, Linnman, Pissiota and Frans21–Reference Furmark, Appel, Michelgård, Wahlstedt, Åhs and Zancan25 and recent work from our lab suggest that SSRI, CBT/ICBT and placebo monotherapies all exert anxiolytic effects through a common pathway including reduction of amygdala reactivity. Reference Faria, Appel, Åhs, Linnman, Pissiota and Frans21–Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters23,Reference Furmark, Appel, Michelgård, Wahlstedt, Åhs and Zancan25 It is thus likely that reduced amygdala reactivity accompanies successful treatment outcome. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has assessed brain correlates of combined treatment with SSRI and CBT. Studies of this kind could be of therapeutic importance, enabling better understanding of the mediating neural mechanisms in pharmacological and psychosocial treatments.

In this double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled neuroimaging trial, we evaluated the effect of SSRI-augmented ICBT for SAD on clinical symptoms, anticipatory anxiety before public speaking and brain reactivity during an emotional face-processing task. Reference Hariri, Mattay, Tessitore, Kolachana, Fera and Goldman26 Assessments were performed before and after 9 weeks of treatment with ICBT combined with escitalopram 20 mg or pill placebo. We hypothesised that escitalopram would enhance the anxiolytic effect of ICBT and that successful treatment would be associated with greater reduction in amygdala reactivity. Reference Faria, Appel, Åhs, Linnman, Pissiota and Frans21–Reference Furmark, Appel, Michelgård, Wahlstedt, Åhs and Zancan25 In addition, we performed exploratory comparisons of treatment-induced changes in amygdala connectivity and whole brain reactivity after the initial 9-week period. A follow-up assessment of clinical symptoms was also administered 15 months after termination of treatment.

Method

Participants

Forty-eight participants (mean age 33.2. years, s.d. = 8.8; 24 women) meeting the DSM-IV 1 criteria for SAD as primary diagnosis were randomised to escitalopram+ICBT or placebo+ICBT. One participant per group was left-handed.

Recruitment procedure

Participants were recruited through newspaper advertisements. Initial screening included the Social Phobia Screening Questionnaire (SPSQ) Reference Furmark, Tillfors, Everz, Marteinsdottir, Gefvert and Fredrikson27 and the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale – self-rated version (MADRS-S) Reference Montgomery and Asberg28 administered online. Patients passing initial screening were interviewed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs and Weiller29 the SAD section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I), Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams30 and they underwent a medical check-up (see online Fig. DS1 for a CONSORT diagram).

Exclusion criteria were: contraindications for magnetic resonance imaging, presence of severe somatic disease or serious psychiatric disorder such as psychosis or severe major depression, treatment for any psychiatric disorder (ongoing or terminated within 3 months), menopause, and drug or alcohol dependency/misuse.

Study design

This was an investigator-initiated, double-blind, randomised, parallel-group clinical trial with ICBT combined either with escitalopram or pill placebo, conducted between September 2011 and September 2013 (trial registration: ISRCTN24929928). ICBT and pharmacological treatments were started simultaneously. Randomisation, stratified by gender and age, was performed by an independent third party (Apoteket Production and Laboratories (APL), Stockholm, Sweden) and determined by a computerised random-number generator in blocks of two. Allocation was implemented by use of numbered containers, and randomisation codes were kept secret at the Uppsala University Hospital Pharmacy until completion of the study.

Study procedure

Participants underwent two functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanning sessions with an emotional face-matching task, one before and one in the last week of treatment, each followed by a behavioural test. After the first session, an experienced psychiatrist (K.W.) assessed baseline symptom severity using the clinician-administered Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) Reference Fresco, Coles, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hami and Stein31 and the allocated treatment was distributed. After the second scanning session, the same psychiatrist again administered LSAS and rated clinical response status using the Clinical Global Impression – Improvement scale (CGI-I). Reference Zaider, Heimberg, Fresco, Schneier and Liebowitz32 Patients receiving CGI-I scores of 1 or 2 (very much or much improved) were defined as treatment responders and patients scoring ⩾3 were non-responders. Reference Zaider, Heimberg, Fresco, Schneier and Liebowitz32 Fifteen months post-treatment, participants completed the self-report version of LSAS (LSAS-SR) online. Reference Fresco, Coles, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hami and Stein31 During the follow-up period, participants were free to initiate any treatment at their own cost.

Treatments

ICBT

The clinician-guided treatment, based on Clark & Wells' model of SAD, Reference Clark, Wells, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope and Schneier33 was delivered via the internet and included nine weekly modules. Reference Furmark, Carlbring, Hedman, Sonnenstein, Clevberger and Bohman6,Reference Andersson, Cuijpers, Carlbring, Riper and Hedman10,Reference Månsson, Carlbring, Frick, Engman, Olsson and Bodlund22,Reference Andersson, Carlbring, Holmström, Sparthan, Furmark and Nilsson-Ihrfelt34,Reference Carlbring, Gunnarsdóttir, Hedensjö, Andersson, Ekselius and Furmark35 Each module contained a reading section: CBT and SAD (module 1), the cognitive model of SAD and cognitive restructuring (modules 2–4), exposure exercises (modules 5–7), and social skills training and relapse prevention (modules 8 and 9). In addition, the patients were given weekly homework assignments. A therapist provided written feedback on each assignment to reinforce and modify the patients' work and thereafter introduced the next week's module. Adherence to ICBT was assessed through registration of each completed module and homework assignment.

Escitalopram

APL, Stockholm, Sweden, prepared identical capsules containing either escitalopram 20 mg (10 mg during the first week) (H. Lundbeck AB, Helsingborg, Sweden) or pill placebo administered once daily during 9 weeks. Adherence to escitalopram was assessed by analyses of blood metabolites at the final visit.

Treatment credibility and masking

Treatment credibility was assessed 1 week after treatment onset by five questions, each yielding scores between 1 (minimum) and 10 (maximum). Reference Furmark, Carlbring, Hedman, Sonnenstein, Clevberger and Bohman6,Reference Borkovec and Nau36 Following treatment, before unmasking, participants were asked to guess which of the two treatment combinations they had received.

Treatment outcome

Clinical outcome measures

The main clinical outcome measures were treatment response according to CGI-I Reference Zaider, Heimberg, Fresco, Schneier and Liebowitz32 and symptom severity as measured with LSAS. Reference Fresco, Coles, Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hami and Stein31 Secondary outcomes were the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS), Reference Mattick and Clarke37 Social Phobia Scale (SPS), Reference Mattick and Clarke37 MADRS-S, Reference Montgomery and Asberg28 Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), Reference Beck, Epstein, Brown and Steer38 and the Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI). Reference Frisch, Cornell, Villanueva and Retzlaff39

Behavioural test, public speaking

After each fMRI session, participants were instructed to give a 2 min speech on a freely chosen topic in front of five to eight silent participants. Anticipatory anxiety was assessed with the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – State version (STAI-S) Reference Spielberger, Gorsuch and Lushene40 immediately after 3 min of speech preparation.

fMRI

Emotional challenge paradigm. An established amygdala-activating paradigm including matching of fearful or angry facial expressions and geometrical shapes Reference Hariri, Mattay, Tessitore, Kolachana, Fera and Goldman26 was used. A target face or shape was displayed at the top of the screen and, by pressing a button with their left or right index finger, participants indicated which one of two lower images displayed the same emotion or shape as the target (online Fig. DS2). Face and shape trials were presented in blocks of six, in which images were presented for 4 s, interspaced with a fixation cross (2 s for shape trials and random duration of 2, 4 or 6 s for face trials). The expressed emotion or shape of the target varied from trial to trial, and each face block had an equal mix of emotions as well as gender of the actors. Accuracy and reaction times were registered for each trial.

Image acquisition. MRI was performed using a Philips Achieva 3.0T whole body MR scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) equipped with an 8-channel head-coil. An anatomical T 1-weighted image (echo time (TE) = 15 ms; repetition time (TR) = 5700 ms; inversion time = 400 ms; field of view = 230 × 230 mm2; voxel size = 0.8 × 1.0 × 2.0 mm3; 60 contiguous slices) and a blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence were acquired (TE = 35 ms; TR = 3000 ms; flip angle = 90°, acquisition matrix = 76 × 77, voxel size = 3.0 × 3.0 × 3.0 mm3, gap = 1 mm, 30 axial slices). Participants were positioned supine in the scanner. Visual stimuli were presented through goggles (Visual System, NordicNeuroLab, Bergen, Norway) using E-prime (Psychology Software Tools, Sharpsburg, Pennsylvania, USA).

Image pre-processing. Data were analysed in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts, USA) using SPM8 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm8). Each participant's BOLD EPI images were realigned to the mean image of each session, slice timing corrected to the middle slice of each volume, co-registered with the anatomical scan and normalised to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standard space using parameters obtained from unified segmentation of the anatomical image. Finally, smoothing was performed using an 8 mm Gaussian kernel (full width, half maximum). BOLD signal in each voxel was high-pass filtered with 128 s, regressed on the stimulus function (boxcar, onsets and durations of face and shape stimuli), six movement parameters obtained from the realignment step and convolved with the canonical haemodynamic response function provided by SPM. For each participant and session, emotional faces were contrasted against geometrical shapes. Psychophysiological interaction (PPI) analyses of amygdala connectivity were conducted with time-series fMRI data extracted from the amygdala, and entered as a regressor together with task and the interaction between the two. For each individual, difference images representing changes in reactivity/connectivity, calculated by subtracting the pre-treatment from the post-treatment contrast map, were used in second level group comparisons.

Statistical analyses

Demographic and pre-treatment clinical data were compared between groups by t-tests, Mann–Whitney U-tests or chi-squared tests using IBM SPSS Statistics 20. Treatment effects were evaluated using repeated measurement ANOVAs with group (escitalopram+ICBT/placebo+ICBT or responders/non-responders) and time (pre- and post-treatment) as factors, with t-test for follow-up analyses. Two participants (one per group) were not available for all post-treatment measurements, and eight (four per group) were unavailable for 15-month follow-up (Fig. DS1), and we therefore performed intention-to-treat analyses on clinical and behavioural measures.

Neural reactivity and connectivity changes in treatment (escitalopram+ICBT v. placebo+ICBT) and response (responders v. non-responders) groups were analysed within SPM8 using between-group t-tests. Follow-up reactivity analyses in responder/non-responder subgroups were conducted to evaluate whether change in amygdala reactivity could be explained by clinical improvement or SSRI administration. The region of interest for the reactivity analyses and extraction of PPI time-series consisted of the bilateral amygdala from the Automated Anatomical Labelling atlas within the Wake Forest University Pick atlas. Reference Maldjian, Laurienti, Kraft and Burdette41 Associations between change in amygdala reactivity and symptom improvement were assessed in the whole sample by including LSAS change scores in regression analyses within SPM8. Spatial localisations are reported in MNI coordinates. The statistical threshold for main fMRI analyses was set at P<0.05 family-wise error corrected (FWE), but as we had a strong a priori hypothesis of attenuated amygdala response following treatment, we balanced the risk for type I and type II errors by also reporting all amygdala voxel values significant at uncorrected P<0.05. Exploratory whole brain reactivity and whole brain PPI analyses applied a statistical threshold of P<0.001 with ⩾10 voxels cluster extent.

Power calculations based on previous SSRI trials Reference Faria, Appel, Åhs, Linnman, Pissiota and Frans21,Reference Lader, Stender, Bürger and Nil42 assumed a difference between escitalopram and placebo in mean (s.d.) LSAS scores of 11.4 (11.7). Given α = 0.05 and n = 24 per group, the study had 80% power to detect a difference between treatments.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Uppsala, and the Medical Products Agency in Sweden. All participants were fully informed about the study aims and procedures and gave written informed consent prior to inclusion.

Results

Pre-treatment

There were no significant differences between groups on any of the demographic variables (Table 1) or outcome measures (online Table DS1) at pre-treatment.

Table 1 Patient characteristics prior to treatment

| Escitalopram+ICBT (n = 24) | Placebo+ICBT (n = 24) | Statistic | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 35.4 (9.8) | 32.2 (8.7) | t = 1.20 | 0.24 |

| Men, n (%) | 24 (50) | 24 (50) | χ2 = 0 | 1 |

| Education ⩾12 years, n (%) | 13 (54) | 12 (50) | χ2 = 0.08 | 0.77 |

| Duration of SAD, mean years (s.d.) | 24.9 (12.2) | 21.0 (11.1) | t = 1.15 | 0.26 |

| Generalised SAD, n (%) | 13 (54) | 17 (71) | χ2 = 1.42 | 0.23 |

| Comorbidity, a n (%) | 11 (46) | 7 (29) | χ2 = 1.42 | 0.23 |

| GAD | 6 (25) | 4(17) | ||

| Specific phobia | 4 (17) | 3 (13) | ||

| Depressive episode, current | 3 (13) | 0 (0) | ||

| Panic disorder | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | ||

| OCD | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Earlier psychological treatment, n (%) | 1 (4) | 3 (13) | 0.61 b | |

| Earlier psychotropic medication, n (%) | 5 (21) | 2 (8) | χ2 = 3.82 | 0.23 |

| SSRI | 3 (3) | 1 (4) | ||

| Unknown antidepressants | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | ||

| Perphenazine | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | ||

GAD, generalised anxiety disorder; ICBT, internet-delivered cognitive-behavioural therapy; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

a. Seven participants in the escitalopram+ICBT group and five in the placebo+ICBT group reported multiple comorbidities.

b. Fisher's exact test.

Treatment outcome

Clinical measures

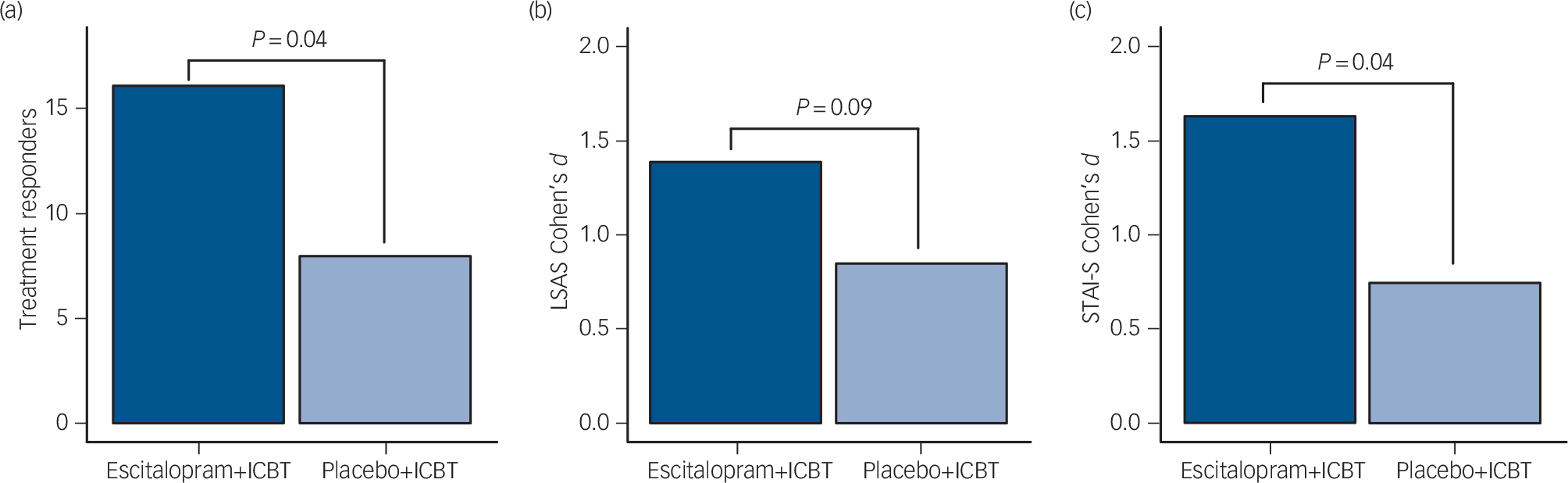

Escitalopram+ICBT yielded a significantly (χ2(1) = 4.08, P = 0.04) higher number of responders (16/24, 67%), according to the CGI-I, compared with placebo+ICBT (8/24, 33%) (Fig. 1). For LSAS, there was a significant main effect of time (F(1,46) = 85.2, P<0.0001) and a trend for a group time interaction (F(1,46) = 2.97, P = 0.09) favouring escitalopram+ICBT at post-treatment (Fig. 1 and Table DS1). Long-term follow-up analysis at 15 months showed a significant interaction group × time (F(2,46) = 3.8, P = 0.03) favouring escitalopram+ICBT (online Table DS2). There was no difference (group × time) on LSAS change scores (pre-treatment to follow-up) between the patients that were on SSRIs during the follow-up period (escitalopram+ICBT: n = 5; placebo+ICBT: n = 6) and those who were not (F(2,38) = 0.07, P = 0.94).

Fig. 1 Comparisons between participants treated with combined escitalopram and internet-delivered cognitive–behavioral therapy (ICBT) (dark blue; n = 24) or combined placebo and ICBT (light blue; n = 24).

(a) Number of treatment responders in each group. (b) Effect sizes of improvement (pre–post) on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS). (c) Effect sizes of improvement in anticipatory speech anxiety (pre–post) as measured by the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – State version (STAI-S).

Behavioural test

For speech anticipatory anxiety (STAI-S), there was a significant main effect of time (F(1,46) = 46.23, P<0.0001) and a group × time interaction (F(1,46) = 4.62, P = 0.04) favouring escitalopram+ICBT (Fig. 1 and Table DS1).

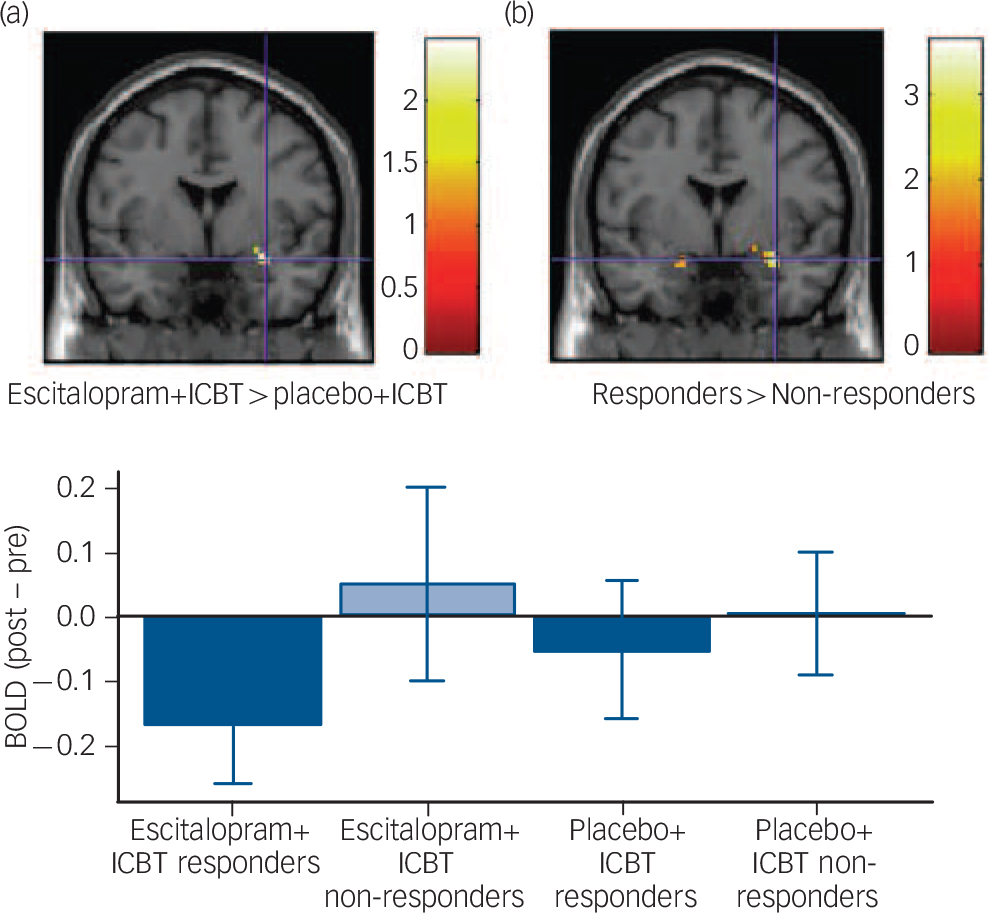

fMRI

Significantly greater reduction (pre- to post-treatment) in amygdala reactivity to the emotional face-matching task was observed in treatment responders compared with non-responders (MNI x, y, z: 33, −1, −17; Z = 3.38, PFWE = 0.019, 27 mm3). In the whole sample, improvement in LSAS scores correlated with reduced right amygdala reactivity (MNI x, y, z: 33, −1, −17; Z = 3.44, PFWE = 0.016, 27 mm3) (online Fig. DS3).

At a more lenient (Puncorrected <0.05) statistical threshold, patients treated with escitalopram+ICBT relative to placebo+ICBT, and responders within each group, showed larger reduction in amygdala reactivity (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Table 2 Treatment-related reductions in amygdala BOLD signal during an emotional face-matching task after treatment with ICBT combined with escitalopram or pill placebo

| Hemisphere | MNI x, y, z | Z | Height P uncorrected |

Cluster volume, mm3 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main analyses | |||||||

| Escitalopram+ICBT > placebo+ICBT | Right | 33 | −1 | −17 | 2.38 | 0.009 | 243 |

| Responders> non-responders | Right | 33 | −1 | −17 | 3.38 | <0.001 b | 513 |

| Left | −18 | −4 | −17 | 2.04 | 0.02 | 324 | |

| Follow-up analyses a | |||||||

| Escitalopram+ICBT responders > escitalopram+ICBT | Right | 33 | −1 | −17 | 2.60 | 0.005 | 81 |

| non-responders | Left | −18 | −7 | −17 | 2.44 | 0.007 | 567 |

| Placebo+ICBT responders>placebo+ICBT non-responders | Right | 30 | −4 | −17 | 2.04 | 0.02 | 108 |

BOLD, blood oxygenation level-dependent; ICBT, internet-delivered cognitive-behavioural therapy; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute.

a. Escitalopram+ICBT responders v. placebo+ICBT responders: no significant clusters. Escitalopram+ICBT non-responders v. placebo+ICBT non-responders: no significant clusters.

b. PFWE =0.019.

Fig. 2 Treatment-related reductions in amygdala reactivity during an emotional face-matching task.

(a) Escitalopram and internet-delivered cognitive–behavioral therapy (ICBT) decreased more than placebo+ICBT in the right amygdala. (b) Treatment responders decreased more than non-responders bilaterally in the amygdala. Crosshair in all images at Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates x, y, z: 33, −1, −17. All images are displayed at P uncorrected<0.05, but the difference between responders and non-responders is also significant at P FWE<0.05. Bar plot depicts mean reduced blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal, parameter estimates (arbitrary units) from pre- to post-treatment. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Neither treatment nor responder groups differed on treatment-induced changes in accuracy or reaction times during the fMRI task (data not shown).

Exploratory fMRI analyses

Whole brain PPI analyses revealed a greater increase in amygdala–insula (Brodmann area (BA) 13) coupling in responders than non-responders (MNI x, y, z: −36, 26, 10; Z = 3.35, Puncorrected <0.001, 270 mm3), and in the whole brain analyses of reactivity, greater attenuation in the escitalopram+ICBT group relative to placebo+ICBT and in responders compared with non-responders was observed in several cortical areas (online Table DS3). Treatment-induced reduction in LSAS score was positively correlated with decreased neural reactivity in the precentral gyrus (BA 6).

Additional analyses

Secondary outcome measures

Both treatment groups improved on all secondary outcome measures with the largest effect sizes found with escitalopram+ICBT. A significant between-group difference (escitalopram+ICBT>placebo+ ICBT) was noted on quality of life (Table DS1).

Adverse events

Significantly (χ2(1) = 11.73, P<0.001) more participants in the escitalopram+ICBT group (22/24, 92%) than in the placebo+ICBT group (11/24, 46%) reported drug-related adverse events, and the escitalopram+ICBT group reported significantly (t(46) = 3.40, P<0.001) more adverse events (mean 2.3, s.d. = 1.3) than the placebo+ICBT group (mean 1.0, s.d. = 1.3). There was no difference in number of adverse events in the responder compared with the non-responder group (t(46) = 0.30, P = 0.77). A total of 41 adverse events were reported in the trial, the most common being nausea (n = 10), headache (n = 7), insomnia (n = 3), increased anxiety (n = 3) and tiredness (n = 2). Events were generally mild or moderate, usually transient and all were resolved at post-treatment.

Adherence to ICBT

There was no significant difference in number of completed modules between treatment groups (Mann–Whitney U = 229.0, P = 0.15). The majority of participants completed all nine modules (escitalopram+ICBT: 18/24, 75%; placebo+ICBT: 14/24, 58%) and all but one participant in each group completed at least five modules. Across both groups, significantly more responders to treatment (20/24, 83%) than non-responders (12/24, 50%) completed all nine modules (χ2(1) = 6.00, P = 0.01), whereas this was not observed within each treatment group (P's>0.12).

Adherence to escitalopram

Blood serum analyses of escitalopram concentrations Reference Reis, Cherma, Carlsson and Bengtsson43 indicated that all participants in the escitalopram+ICBT group (median (25th–75th percentile) 65.0 (39.5–103.0) nmol/L), but none in the placebo+ICBT group (0 (0–0) nmol/L), had taken the medication. One person in the placebo+ICBT group discontinued treatment owing to side-effects (feeling emotionally unaware), but participated in post-assessments.

Relapse

Following Montgomery et al, Reference Montgomery, Nil, Dürr-Pal, Loft and Boulenger44 relapse was defined as an increase >10 in LSAS score from post-assessment to 15-month follow-up. Four participants (4/40; 10%) relapsed, two in each treatment group, three of which being responders (escitalopram+ICBT: n = 2; placebo+ICBT: n = 1). The responder who relapsed in the placebo+ICBT group had also started SSRI treatment during the follow-up period.

Expectancy and credibility

There were no significant differences between treatment groups regarding total credibility score (t(45) = 1.26, P = 0.22) or expectancy of improvement (t(45) = 1.24, P = 0.22). Participants were not able to guess their treatment at better than chance level (χ2(1) = 1.73, P = 0.19).

Discussion

Summary of findings

This randomised, double-blind, pharmaco-fMRI trial indicates that adding escitalopram to ICBT for SAD increases the number of responders, reduces anticipatory speech anxiety, and attenuates amygdala reactivity to an emotional face-matching task. Fifteen-month follow-up data corroborated the beneficial clinical effect. These findings are in line with clinical observations that SSRIs may enhance the effect of CBT and are in agreement with observations from neuroimaging trials that attenuation of amygdala reactivity may underlie symptom improvement in patients with anxiety disorder. Reference Faria, Appel, Åhs, Linnman, Pissiota and Frans21–Reference Furmark, Tillfors, Marteinsdottir, Fischer, Pissiota and Långström23,Reference Furmark, Appel, Michelgård, Wahlstedt, Åhs and Zancan25

Behavioural treatment effects

Only two prior studies have reported on clinical effects of concurrent SSRI and CBT treatment for SAD, with mixed findings. Reference Blomhoff, Haug, Hellström, Holme, Humble and Madsbu12,Reference Davidson, Foa, Huppert, Keefe, Franklin and Compton13 Davidson et al Reference Davidson, Foa, Huppert, Keefe, Franklin and Compton13 found no benefit of adding fluoxetine to CBT, whereas Blomhoff et al Reference Blomhoff, Haug, Hellström, Holme, Humble and Madsbu12 suggested a possible advantage of combined sertraline and behaviour therapy relative to behaviour treatment alone. In addition, combining the monoamine oxidase inhibitor phenelzine with group CBT was superior to either treatment alone in one trial. Reference Blanco, Heimberg, Schneier, Fresco, Chen and Turk45 In line with the present findings, the combination of SSRI and CBT has shown positive effects in other anxiety and mood disorders in adults Reference Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Koole, Andersson, Beekman and Reynolds15 and in adolescents. Reference Walkup, Albano, Piacentini, Birmaher, Compton and Sherrill14 There were no indications that the add-on effect of escitalopram was due to reduction of depressive symptoms. Concomitant SSRI treatment could, however, help build resilience with CBT by enhancing extinction learning Reference Karpova, Pickenhagen, Lindholm, Tiraboschi, Kulesskaya and Ágústsdóttir16,Reference Bui, Orr, Jacoby, Keshaviah, LeBlanc and Milad17 or by reducing anxiety Reference Lader, Stender, Bürger and Nil42,Reference Montgomery, Nil, Dürr-Pal, Loft and Boulenger44 or cognitive biases. Reference Harmer and Cowen46 Interestingly, at 15-month follow-up, the escitalopram+ICBT group had lower LSAS scores than the placebo+ICBT group, indicating stable long-term improvement of adding escitalopram to CBT for SAD.

Neural treatment effects

The fMRI data suggested that amygdala reactivity to emotional faces was more attenuated in responders as well as in the escitalopram+ICBT group, consistent with the notion that dampened amygdala activation constitutes a common anxiolytic pathway for various SAD treatments. Reference Faria, Appel, Åhs, Linnman, Pissiota and Frans21–Reference Furmark, Tillfors, Marteinsdottir, Fischer, Pissiota and Långström23,Reference Furmark, Appel, Michelgård, Wahlstedt, Åhs and Zancan25 We have previously shown that the clinical response following treatment with SSRI, Reference Faria, Appel, Åhs, Linnman, Pissiota and Frans21,Reference Furmark, Tillfors, Marteinsdottir, Fischer, Pissiota and Långström23,Reference Furmark, Appel, Michelgård, Wahlstedt, Åhs and Zancan25 CBT Reference Furmark, Tillfors, Marteinsdottir, Fischer, Pissiota and Långström23 and placebo Reference Faria, Appel, Åhs, Linnman, Pissiota and Frans21 is associated with reduced amygdala reactivity to symptom provocation (i.e. public speaking). Here, we extend these findings to include combined treatment and a different end-point of neural response, an emotional face-matching task. Similar to the results by Faria et al, Reference Faria, Appel, Åhs, Linnman, Pissiota and Frans21 attenuation of especially the right amygdala was associated with clinical response, both in between-group comparisons and as reflected in the positive correlation between symptom improvement and reduced amygdala reactivity. We argue that our amygdala results reflect anxiolytic rather than general pharmacodynamic effects, Reference Faria, Appel, Åhs, Linnman, Pissiota and Frans21 as escitalopram+ICBT non-responders did not show diminished amygdala reactivity, whereas placebo+ICBT responders did. This notion is also supported by the lack of evidence for differential amygdala reduction between escitalopram+ICBT responders v. placebo+ICBT responders.

Amygdala connectivity to the right insula increased in responders, indicating that the successful treatment alters inter-connectivity between central nodes of the fear processing network. We could, however, not demonstrate evidence for treatment-related changes in amygdala-frontal connectivity, putatively involved in symptom improvement through enhanced emotion regulation. Reference Goldin, Manber, Hakimi, Canli and Gross20 Aside from the amygdala, reduced symptom (LSAS) severity also had a positive correlation with diminished reactivity in the precentral motor cortex (BA 6), again with escitalopram+ICBT exhibiting the greatest reduction, possibly reflecting improvement in the motor component of anxiety Reference Åhs, Pissiota, Michelgård, Frans, Furmark and Appel47 or changes in the salience network. Reference Seeley, Menon, Schatzberg, Keller, Glover and Kenna48

Limitations

Among the study limitations it should be noted that we could not directly compare combined treatment with monotherapies, although we note relatively higher effect sizes on comparable social anxiety scales for escitalopram+ICBT in comparison with ICBT alone as reported in our previous large-scale randomised controlled trials using the same ICBT treatment programme. Reference Furmark, Carlbring, Hedman, Sonnenstein, Clevberger and Bohman6,Reference Andersson, Carlbring, Holmström, Sparthan, Furmark and Nilsson-Ihrfelt34,Reference Carlbring, Gunnarsdóttir, Hedensjö, Andersson, Ekselius and Furmark35 Also, our findings of stable long-term improvement for escitalopram+ICBT even after termination of the drug treatment period, with low relapse rate in comparison to previous data on long-term administration of escitalopram v. placebo, Reference Montgomery, Nil, Dürr-Pal, Loft and Boulenger44 suggest SSRI potentiation of CBT learning rather than a mere drug effect. The present design did not include a control for placebo+ICBT but this treatment yielded considerably higher effects sizes than waiting-list Reference Furmark, Carlbring, Hedman, Sonnenstein, Clevberger and Bohman6,Reference Andersson, Carlbring, Holmström, Sparthan, Furmark and Nilsson-Ihrfelt34,Reference Carlbring, Gunnarsdóttir, Hedensjö, Andersson, Ekselius and Furmark35 and placebo Reference Faria, Appel, Åhs, Linnman, Pissiota and Frans21 comparison groups in our previous reports, and similar effect sizes as for ICBT monotherapy. Reference Furmark, Carlbring, Hedman, Sonnenstein, Clevberger and Bohman6,Reference Andersson, Carlbring, Holmström, Sparthan, Furmark and Nilsson-Ihrfelt34,Reference Carlbring, Gunnarsdóttir, Hedensjö, Andersson, Ekselius and Furmark35 Further limitations include the relatively modest sample size especially when comparing responders with non-responders within treatments. Also, the failure to show a significant effect on the LSAS at post-treatment may have been due to the low sample size, given the fact that the patients also had an additional treatment, ICBT, which may further reduce the difference between active drug and placebo. Although our main fMRI results of a larger reduction in amygdala reactivity connected to symptom improvement rely on corrected P-levels, we also chose to report results at a more liberal level with uncorrected P-values. We are aware that this approach may increase the risk of false positives; however, an overly strict approach may also lead to type II errors which we think might otherwise have been present as the pattern of results observed was highly consistent with our previous imaging treatment studies. Reference Faria, Appel, Åhs, Linnman, Pissiota and Frans21–Reference Furmark, Tillfors, Marteinsdottir, Fischer, Pissiota and Långström23,Reference Furmark, Appel, Michelgård, Wahlstedt, Åhs and Zancan25

Implications

To our knowledge, this is the first randomised neuroimaging trial of combined first-line pharmacological and psychosocial treatments. We demonstrate that the SSRI escitalopram adds to the clinical effect of CBT for SAD and that decreased amygdala reactivity may serve as a biomarker for successful anxiolytic treatment.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.