Debates concerning the putative enhancement of human cognition often revolve around two issues: one technical, the other ethical – can pharmacology enhance human intelligence and should this be something that society encourages, tolerates or proscribes? 1,Reference Harris2 If the first of these questions were to be resolved positively (i.e. if so-called ‘smart’ drugs were proven to enhance cognition) then further concerns might readily arise: would some people gain ‘unfair’ advantage by ‘enhancing’ themselves, for example, through the covert use of drugs, and would others feel compelled, or even be coerced, into following them? 1 Therefore, in such accounts, a ‘better’ human is usually assumed to be a ‘smarter’ human, more intelligent (note also, that as in other areas of biological ‘enhancement’, e.g. the embellishment of athletic prowess or beauty, the advantage conferred appears to be essentially competitive). However, from a societal perspective, such a conflation of ‘cognition’ with ‘intelligence’, and the accompanying emphasis upon competitive advantage, seem to overlook something important – from the vantage point of the early 21st century, surveying human conduct throughout the recent past, might we be inclined to ask: were the shortcomings exhibited by humanity principally those incurred by insufficient intelligence or were they attributable to some other form of mental or moral failure? Reference Glover3 To emphasise this point: would ‘brighter’ humans have been any less likely to have devised the Holocaust, slaughtered their neighbours in Rwanda, or committed atrocities in Bosnia and Darfur?

Recent considerations of the ethics of cognitive enhancement have specifically excluded consideration of social cognitions (such as empathy, revenge or deception), on the grounds that they are less amenable to quantification. 1 Nevertheless, it would be regrettable if this limitation entirely precluded consideration of what must be an important question for humanity: can pharmacology help us enhance human morality? Might drugs not only make us smarter but also assist us in becoming more ‘humane’?

When voiced in such a way, this proposal can sound absurd, not least since we may suspect that such mental manipulation would render us ‘artificially’ moral. Where would be the benefit of being kinder or more humane as a consequence of medication? This is an understandable (though reflexive) response. However, if we stop to consider what is actually happening in certain psychiatric settings, then we may begin to interrogate this proposal more systematically. I shall argue that within many clinical encounters there may already be a subtle form of moral assistance going on, albeit one that we do not choose to describe in these terms. I argue that we are already deploying certain medications in a way not totally dissimilar to the foregoing proposal: whenever humans knowingly use drugs as a means to improving their future conduct.

Means and ends

I should state clearly that there are different ways in which one might construe pharmacology as enhancing morality, and that these vary from what could be called a ‘Promethean’ project Reference Harris2 (e.g. specifically designing drugs that target and increase a prosocial feeling and behaviour such as ‘kindness’) to the more prosaic situation, encountered clinically, where a beneficial consequence of pharmacological treatment is the well-being of others (e.g. a man prone to psychosis, who can be violent when ill, takes his medication reliably, thereby reducing his risk to others). However, no matter what the technical means deployed, whether the intervention assists in ‘moral enhancement’ or not, depends crucially upon the goals of the patient concerned, i.e. what are the ‘ends’ that he is pursuing?

Clinical realities

Consider three clinical examples, each involving antipsychotic medication, none of which is unusual.

-

(a) A man lacking insight into his psychotic illness does not believe that he is ill and is formally detained in hospital. Reluctantly, he accepts medication because he ‘has to’. In this scenario, there is no ground for invoking moral (or immoral) conduct: the patient is not ‘responsible’ for his actions and while he lacks insight, he cannot be ‘blamed’ for resisting treatment; his illness deprives him of moral agency (for the time being).

-

(b) A second man suffers from a psychotic illness. When this man is ill he can be very violent towards others. The pattern of his illness is that he recovers when treated but then stops his medication and returns to using large quantities of crack cocaine. To some extent, the consequences of his conduct are predictable. Is there a moral dimension to his behaviour? Well, it can be argued that there is: for during those periods when he was ‘well’ he might have chosen to reduce his risk to others by remaining in treatment. When viewed externally, his repeated resort to cocaine appears reckless. Unsurprisingly, some authors would hold him partially responsible for his next relapse (and for its harmful consequences). Reference Mitchell4

-

(c) Meanwhile, in a clinic, there is a third man. He attracts a diagnosis of ‘antisocial personality disorder’. Now, this man actually requests ‘antipsychotic’ medication as a way of reducing his impulsivity and, in turn, his liability to react aggressively towards others. He has a girlfriend; he does not wish to hurt her. In this case, if taken at face value, the patient is clearly attempting to influence his own future conduct. He is anticipating using pharmacology as a means to an end; and if he is doing so consciously (and sincerely), then he is exhibiting moral agency.

Hence, if we ask the question ‘Can pharmacology help to enhance human morality?’ then we should answer ‘yes’, that sometimes it can be used as a means to this end but a lot depends upon clarifying the intentions, the ‘ends’, of those who use it.

Preventing harm

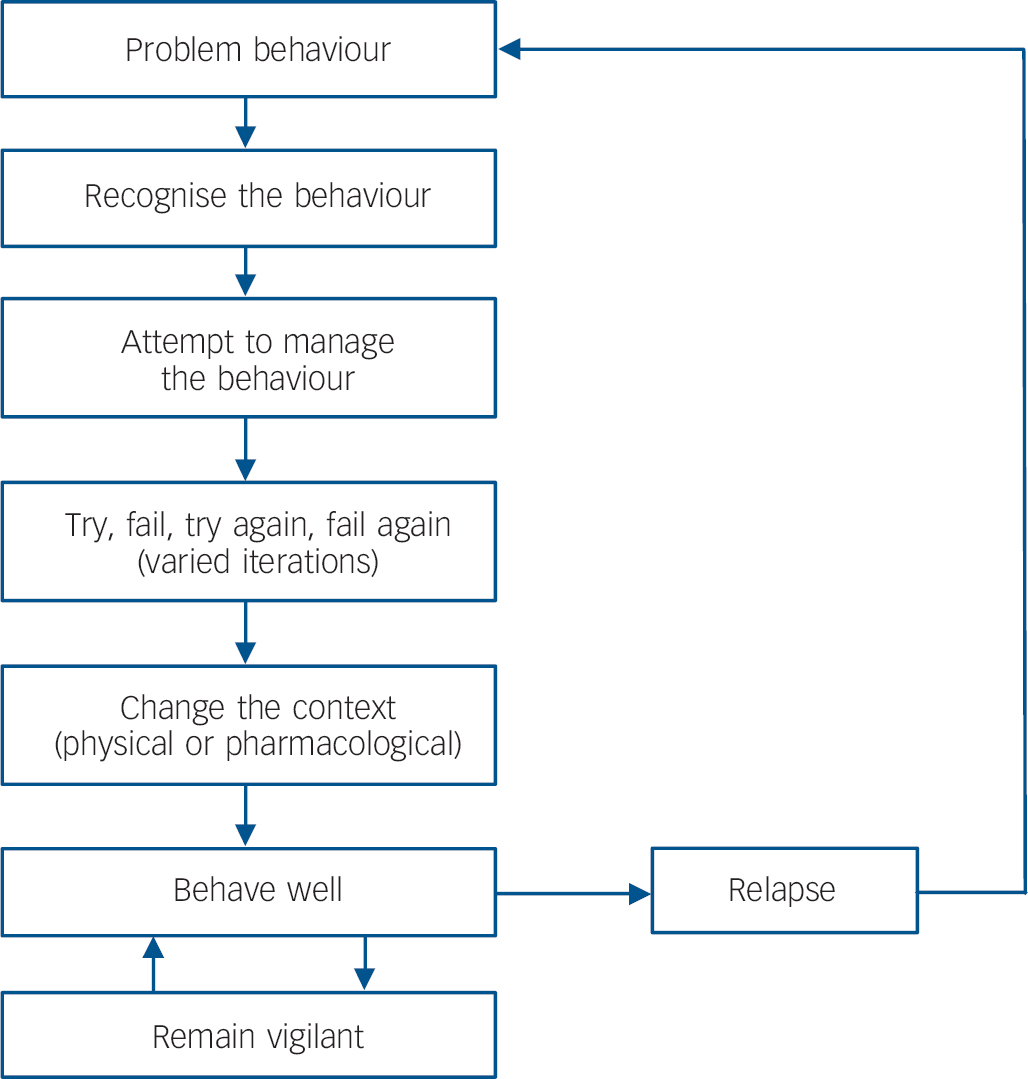

Many patients are attempting to bring about positive, prosocial ends, through their actions in the present. An ex-substance user or alcoholic may cease to mix with former friends because, for example, those friends are ‘still using’ or drinking. Similarly, an ex-offender may avoid former associates because he wants to ‘go straight’. These people are acting responsibly: they are adapting their current environment, hoping to do the right thing (both now and in the future; Fig. 1).

Are medicines deployed towards such ends? Yes, as illustrated above, psychiatric practice evinces suitable exemplars. Wherever patients take prophylactic medication that helps prevent the relapse of a condition that might lead to aberrant behaviour, harming themselves or others, they have behaved responsibly. If they specifically intend to protect others then they are behaving morally, altruistically. Hence, the antipsychotics and mood stabilisers taken by those with major psychoses, the anticraving, substitute and deterrent medications taken by those with addictions (especially disulfiram, given the serious consequences of any subsequent relapse), the antipsychotics accepted by those with personality disorders to reduce their impulsivity and aggression, the antilibidinal medicines accepted by sex offenders, all represent manifestations of a sense of responsibility that is potentially altruistic if it aims to safeguard the well-being of others, either through reducing direct physical harm to them or by reducing their vicarious exposure to suffering (as family members and carers).

Hence, it is not that taking medicine is intrinsically moral or immoral, it is that a human subject can use medication as a means to assist them towards a moral end: reducing future harm. Such a person exhibits altruism.

Concluding remarks

My purpose in pursuing this line of argument has been to open up a space for discussion, specifically concerning the possible improvement of human behaviour. How might we help people to help themselves? How might they sculpt their own futures, constructively? As we have seen, clinical psychiatry illustrates such a paradigm: at times, medications are deployed to reduce the likelihood of harmful behaviours driven by psychosis, addiction, personality or sexual preference. It seems that there are already times when pharmacology is helping people to shape their future conduct.

Fig. 1 Preventing harm by adapting the current environment.

A moral agent's responsible attempts to modulate their future conduct, whether by contextual means (e.g. avoiding certain environments and company) or pharmacological treatment (e.g. taking anticraving medications). In such cases pharmacology may provide a means to be deployed towards prosocial ends.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their incisive comments on an earlier draft; to the publications of E. W. Mitchell, for alerting me to the concept of meta-responsibility; and to Mrs Jean Woodhead for assistance in manuscript preparation.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.