Betel-quid, the fourth most frequently consumed psychoactive substance worldwide, is a masticatory mixture combining the areca nut, betel leaf, slaked lime and locally varied flavourings. Reference Lee, Ko, Warnakulasuriya, Yin, Sunarjo and Zain1 According to estimates, at least 10% of the world population chew some variety of betel-quid. Reference Gupta and Ray2 Studies of the chemical constituents have demonstrated that the areca nut contains 11–26% tannins and 0.15–0.67% alkaloids. Reference Lord, Lim, Warnakulasuriya and Peters3,Reference Changrani and Gany4 Among these, arecoline (the nut's major alkaloid) has a chemical structure comparable to nicotine. Reference Lord, Lim, Warnakulasuriya and Peters3 The addictive properties of the areca nut have been recognised by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) since 1985, 5 but data are sparse on the syndromes of betel-quid dependence among those who chew this mixture and the prevalence of dependency in the general population. In 2004 the IARC concluded that betel-quid is carcinogenic to humans (group 1), 6 and later it has been linked to early tumour onset and an increased risk of contracting upper aerodigestive malignancies. Reference Lee, Lee, Fang, Wu, Shieh and Huang7–Reference Lee, Lee, Fang, Wu, Tsai and Chen13 Furthermore, its prolonged use has been reported to increase the risk of chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease and of adverse pregnancy outcomes such as low birthweight. Reference Lee, Ko, Warnakulasuriya, Yin, Sunarjo and Zain1,Reference Yang, Lee, Chang, Chung, Tsai and Ko14 Oral lichen planus, oral submucous fibrosis and oral leukoplakia are a group of oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMD) thought to be linked to the development of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Despite the gradual understanding of the multidimensional health consequences of chewing, little is actually known concerning the effects of dependent betel-quid use on this group of oral precancerous disorders.

In 2008 the Centre of Excellence for Environmental Medicine at Taiwan Kaohsiung Medical University and the World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer and Precancer in the UK initiated the Asian Betel-quid Consortium (ABC) study. The consortium studied the intercountry effects of betel-quid use, health consequences of dependent use and methods of mobilising outreach actions for the prevention of oral disease. Reference Lee, Ko, Warnakulasuriya, Yin, Sunarjo and Zain1,Reference Lee, Ko, Warnakulasuriya, Ling, Sunarjo and Rajapakse15 The consortium study objectives were, first, to delineate the 12-month prevalence patterns of betel-quid dependence among six diverse Asian populations using DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria for substance use disorder; 16,17 second, to investigate country-dependent factors explaining such dependence; and third, to examine the prevalence and risk of OPMD associated with betel-quid dependency.

Method

Study sample

Six large research centres in east, southern and south-east Asia conducted this international study, including Kaohsiung Medical University (Taiwan), Central South University (mainland China), the University of Peradeniya (Sri Lanka), Kathmandu University (Nepal), the University of Malaya (Malaysia) and Airlangga University (Indonesia). To work towards a comparative framework, identical protocols and a standardised questionnaire were administered in all investigated communities. The ethical review committee from each research centre approved the study proposal. Participant recruitment started in January 2009 and concluded in February 2010. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. Study populations included inhabitants of southern Taiwan, the Hunan province of mainland China, middle Nepal, the central province of Sri Lanka, the Selangor, Sabah and Sarawak states of Malaysia, north Sumatra, east Java, Bali, west Nusa Tenggara, south Sulawesi and the Papua provinces of Indonesia (see online Fig. DS1). The method is described elsewhere. Reference Lee, Ko, Warnakulasuriya, Yin, Sunarjo and Zain1 Briefly, a multistage random sampling method was used to select representative samples from the civilian, non-institutionalised population (15 years and older) in each study community. The chosen study areas are detailed in online Table DS1. The number of participants recruited from each study centre ranged from 1002 to 2356, with a high response rate (68–100%).

Measures

Data were collected using a standardised questionnaire adapted from WHO surveys and other nationwide prevalence studies.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, educational level, occupation and socioeconomic status were recorded.

Substance consumption

Details of patterns of betel-quid, alcohol and tobacco use comprised types consumed, age at initial use, daily consumption, use frequency, years of substance use and achievement of abstinence.

Dependency domains and determination

Eight domains derived from module E (substance use disorders) of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders and from the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry were used to measure DSM-IV and ICD-10 dependence. Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams18,19 These domains were:

-

(a) tolerance;

-

(b) withdrawal;

-

(c) larger intake (betel-quid is chewed in larger amounts or for longer periods than intended);

-

(d) unsuccessful cut-down (unsuccessful efforts to reduce or control betel-quid use);

-

(e) time spent chewing (spending large amounts of time obtaining betel-quid or chewing it);

-

(f) given up activities (reduction in important social, occupational or recreational activities because of betel-quid use);

-

(g) continued despite problems (continued betel-quid chewing despite awareness of physical or psychological problems caused by this habit);

-

(h) craving (a strong desire or sense of compulsion to chew betel-quid).

Betel-quid chewers were defined as people who had consumed at least one quid of any type of betel or areca nut product per day for a minimum of 6 months. Among them, a positive diagnosis of DSM-IV dependency required three or more of domains (a) to (g) presented in the 12-month period preceding our interview. A positive diagnosis of ICD-10 dependency required at least three of domains (a) to (c), (e) and (g) or (h) presented in the past 12 months. Participants who met either DSM-IV or ICD-10 diagnostic criteria were defined as those experiencing any betel-quid dependency.

Betel-quid accessibility

Seven features of environmental accessibility, including easy availability, low cost, ready-made packaging, attractive packaging, aggressive marketing, advertisements for betel-quid and misleading advertisements, as well as three preventive activities (betel-quid-related bans, statutory warnings and health education awareness programmes) were measured (online Table DS2).

Data collection

The questionnaire was written first in English and translated into the appropriate language or dialect for each study population. The questionnaires were back-translated into English to verify their validity. A principal investigator at each study centre organised a team of dentists and dental hygienists, medical officers, interviewers and data-recording clerks. Under the direction of the team's principal investigator, interviewers completed a training programme designed for data collection prior to conducting face-to-face interviews. Using portable dental lights for illumination and plane dental mirrors for soft tissue retraction, dental professionals who had completed standardised training for diagnosing OPMD performed oral cavity examinations. The location and symptoms of oral lesions were carefully inspected based on WHO clinical criteria. Reference Kramer, Pindborg, Bezroukov and Infirri20

Statistical analysis

The data were first prepared by calculating complex sampling weights. Stata version 11 (for Windows) survey data statistical procedures were then implemented to accommodate the complex sampling design. Analyses were performed in three stages. First, point estimates for the prevalence rates, means and percentages regarding betel-quid dependency status from each study area were calculated. Second, polytomous logistic regression models were applied to weighted data in evaluations of the influence of demographic factors and betel-quid usage features on non-dependent and dependent chewing. This type of logistic regression model enables simultaneous comparisons of a categorical dependent outcome with more than two levels. Finally, a binary logistic regression was used to model the effects of non-dependent and dependent chewing on the presence of oral lichen planus, oral submucous fibrosis, oralleukoplakia andOPMD. Theadjustedoddsratiosof contracting OPMD associated with the DSM-IV and ICD-10 symptom count (measured in numbers of those satisfying DSM-IV and ICD-10 dependence domains) were calculated using area-combined data. Furthermore, we employed principal component analysis and biplot to illustrate the relationship between betel-quid dependency domains and six Asian populations.

Results

Selected sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table DS1. Differences in age and gender distributions existed across the study areas. Taiwanese, mainland Chinese and Sri Lankan participants had higher education levels. These divergences were accounted for during interpopulation comparisons.

Prevalences of betel-quid dependency and dependence symptoms

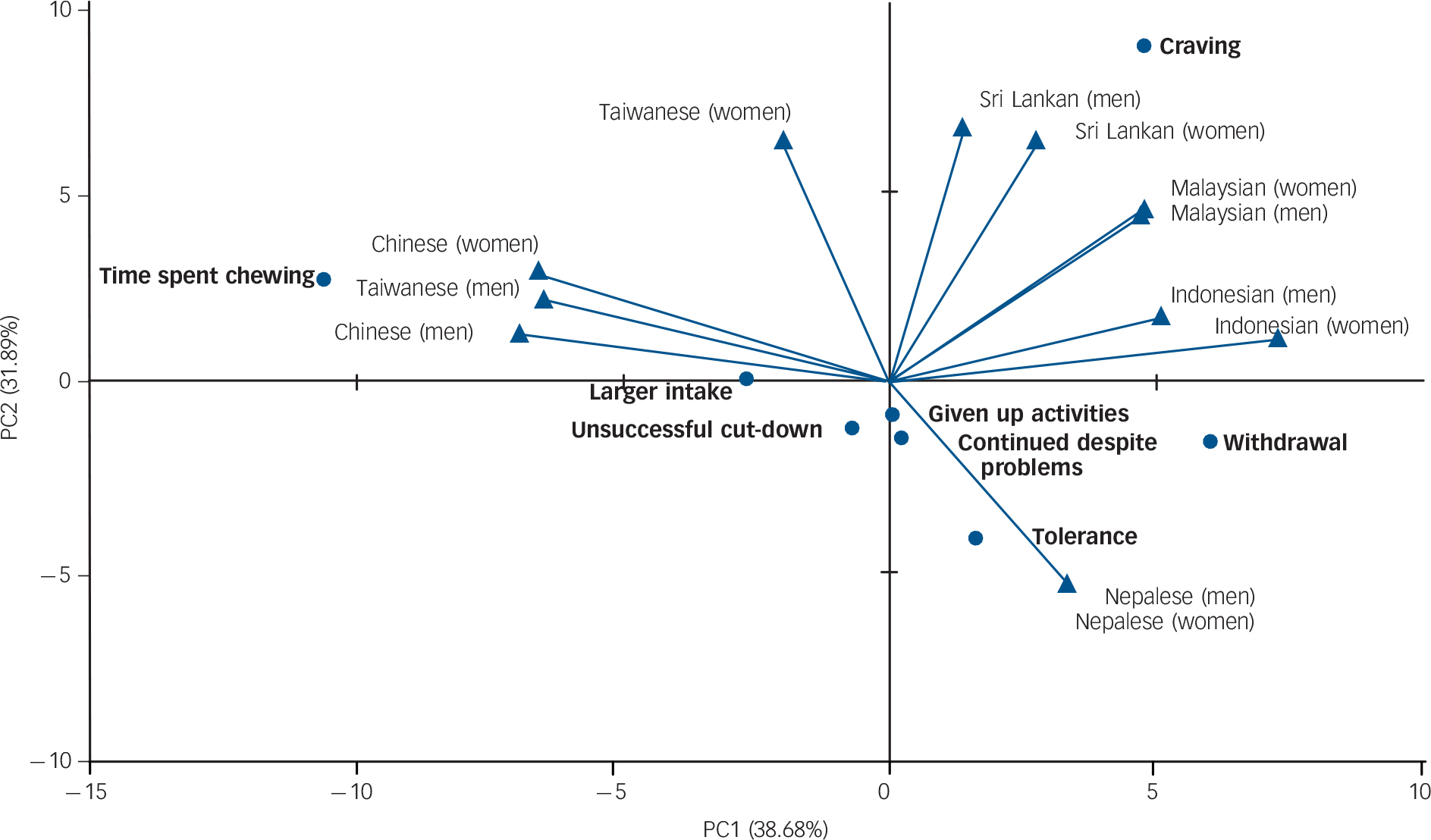

The 12-month betel-quid dependency prevalence defined by either DSM-IV or ICD-10 criteria was found to be higher in men (3.5–7.7%) than in women (0.3–1.1%) in Taiwan and mainland China, and higher in women (7.7–40.5%) than in men (2.0–10.0%) in Malaysia and Indonesia (Table 1). The maximum and minimum prevalences of any betel-quid dependency occurred respectively in Nepal (39.2%) and Taiwan (2.8%; Fig. DS1). The prevalence of any betel-quid dependency was positively correlated with age in many male and female study groups (P⩽0.048 for trend) but negatively correlated with age in Hunan male respondents (P<0.001 for trend). Among those who currently chewed betel-quid, the proportion of dependency was 20.9–33.3% in mainland China and Sri Lanka, 41.3–52.8% in Taiwan and Malaysia and 84.4–99.6% in Indonesia and Nepal. Two principal components were found to explain 70.6% of the variance of dependence symptoms in investigated populations (Fig. 1). The biplot revealed that among those who chewed betel-quid, dependency domains were more correlated within the six south and south-east Asian groups, within the four east Asian groups and within the two Nepalese groups. These three groups were clustered in the first, second and fourth quadrants. ‘Craving’ and ‘time spent chewing’ were the most important dependency domains for populations of Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Indonesia and of Taiwan and mainland China respectively, because their positions were nearest to the respective clusters. In contrast, ‘tolerance’ and ‘withdrawal’ were the major domains for the Nepalese population. In the three group clusters, 70.2–89.9%, 43.3–60.7% and 98.9–99.6% of participants who chewed betel-quid were found to have ‘craving’, ‘time spent chewing’ and ‘tolerance’ plus ‘withdrawal’ respectively (Table 1).

TABLE 1 Prevalence rates of 12-month betel-quid dependence and distribution of dependence symptom domains

| Taiwan | Mainland China | Malaysia | Indonesia | Nepal | Sri Lanka | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men n = 736 |

Women n = 812 |

Men n = 1225 |

Women n = 1131 |

Men n = 383 |

Women n = 620 |

Men n = 965 |

Women n = 976 |

Men n = 664 |

Women n = 338 |

Men n = 385 |

Women n =687 |

|||

| Population prevalence, % | ||||||||||||||

| Current chewer | 10.7 | 2.5Footnote ** | 23.9 | 1.8Footnote ** | 9.8 | 29.5Footnote ** | 12.0 | 46.8Footnote ** | 43.6 | 34.9 | 18.0 | 13.5 | ||

| Betel-quid dependency rate | ||||||||||||||

| DSM-IV criteria | 4.2 | 1.1Footnote ** | 7.7 | 0.4Footnote ** | 2.0 | 7.7Footnote ** | 10.0 | 40.5Footnote ** | 43.5 | 34.5 | 3.8 | 2.5 | ||

| ICD-10 criteria | 3.51.1Footnote * | 6.0 | 0.3Footnote ** | 4.8 | 11.9Footnote ** | 5.5 | 34.4Footnote ** | 39.8 | 33.6 | 4.3 | 2.5 | |||

| Any criteriaFootnote a | 4.5 | 1.1Footnote ** | 8.0 | 0.4Footnote ** | 5.2 | 12.2Footnote ** | 10.1 | 41.5Footnote ** | 43.5 | 34.5 | 4.5 | 2.8 | ||

| Age-specific prevalence (any criteria) |

||||||||||||||

| ⩽30 years | 2.9 | 0.0 | 10.9 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 15.4 | 46.0 | 28.7 | 0.5 | 0.0 | ||

| 31-40 years | 4.7 | 0.0 | 10.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 13.2 | 31.2 | 39.9 | 33.6 | 6.9 | 0.6 | ||

| 41-50 years | 4.9 | 1.8 | 7.9 | 1.0 | 11.9 | 22.9 | 12.4 | 55.9 | 41.5 | 46.5 | 14.4 | 4.0 | ||

| ⩾51 years | 5.7 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 13.7 | 38.2 | 19.0 | 79.8 | 41.9 | 56.8 | 3.1 | 7.2 | ||

| P for linear trend | 0.288 | 0.008 | <0.001 | 0.533 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.642 | 0.048 | 0.038 | <0.001 | ||

|

Betel-quid chewer group

Dependence symptom domain in chewers, % |

||||||||||||||

| Tolerance | 25.8 | 30.4 | 10.9 | 13.6 | 9.8 | 23.5 | 11.5 | 53.3 | 99.6 | 98.9 | 12.0 | 10.7 | ||

| Withdrawal | 23.0 | 21.4 | 18.2 | 15.6 | 73.1 | 64.6 | 89.1 | 88.7 | 99.6 | 98.8 | 7.2 | 10.2 | ||

| Larger intake | 25.0 | 21.3 | 31.9 | 21.5 | 10.6 | 26.7 | 7.4 | 35.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 40.8 | 17.0 | ||

| Unsuccessful cut-down | 37.3 | 36.0 | 28.4 | 24.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 78.3 | 60.7 | 99.6 | 98.9 | 26.9 | 32.5 | ||

| Time spent chewing | 60.7 | 59.8 | 49.3 | 43.3 | 20.4 | 18.8 | 13.7 | 19.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18.8 | 11.5 | ||

| Given up activities | 37.7 | 15.7 | 25.5 | 12.7 | 14.3 | 10.8 | 93.0 | 76.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.9 | 8.8 | ||

| Continued despite problems | 30.6 | 22.7 | 31.2 | 21.5 | 42.5 | 13.7 | 43.6 | 62.9 | 91.3 | 96.2 | 15.8 | 18.5 | ||

| Craving | 31.1 | 64.0 | 18.5 | 20.1 | 84.7 | 70.2 | 87.8 | 89.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 80.1 | 72.7 | ||

| Betel-quid dependency rate, % | ||||||||||||||

| DSM-IV criteria | 39.3 | 45.1 | 32.0 | 24.5 | 20.8 | 26.1 | 83.9 | 86.6 | 99.6 | 98.9 | 21.2 | 18.5 | ||

| ICD-10 criteria | 32.8 | 45.1 | 24.9 | 15.4 | 48.8 | 40.4 | 46.3 | 73.6 | 91.3 | 96.2 | 23.9 | 18.6 | ||

| KappaFootnote b | 0.742Footnote ** | 1.000Footnote ** | 0.779Footnote ** | 0.708Footnote ** | 0.381Footnote ** | 0.659Footnote ** | 0.389Footnote ** | 0.367Footnote ** | 0.211Footnote ** | 0.488Footnote ** | 0.901Footnote ** | 0.803Footnote ** | ||

| Any criteriaFootnote a | 41.7 | 45.1 | 33.3 | 24.5 | 52.8 | 41.3 | 84.4 | 88.7 | 99.6 | 98.9 | 24.9 | 20.9 | ||

a Betel-quid dependence determined by meeting any DSM-IV or ICD-10 criteria.

b Kappa value for the agreement of dependence diagnoses using DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria.

* P<0.05,

** P<0.01 for significantly higher age-adjusted gender difference.

Non-dependent and dependent chewing

Table 2 shows the influence of sociodemographic factors and concomitant use of alcohol and tobacco on betel-quid dependency across various populations. Findings from Nepal were presented for dependent chewing only because the overwhelming majority of participants who chewed betel-quid were dependent users. In Malaysia, Indonesia and Sri Lanka, dependency was related to older age, but in mainland China it was related to younger age. Compared with those with 10 or more years of schooling, participants from Taiwan, Malaysia and Sri Lanka with 6 years of schooling or less had 3.4–4.8 and 3.1–27.2 times greater risks of becoming non-dependent and dependent chewers respectively. In the Sri Lankan sample, a heterogeneously higher risk of becoming dependent was observed (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 5.4). Those who drank alcohol were more likely to be dependent on betel-quid (adjusted OR 2.1–12.7), except in Indonesia. In Malaysia and Indonesia, tobacco smokers were less likely to have any betel-quid dependency than non-smokers (adjusted OR 0.04–0.3). The amount and frequency of betel-quid consumption were significant predictors of dependency among mainland Chinese, Malaysian, Indonesian and Sri Lankan chewers (adjusted OR 1.1–1.5 and 1.4–1.8 respectively). In the Sri Lankan samples, tobacco-added betel-quid created a 5.8-fold higher risk of dependency than tobacco-free betel-quid, whereas in Hunan a family history of betel-quid use showed an appreciable influence on dependency (adjusted OR 2.6).

FIG. 1 Principal component analysis and biplot of the betel-quid dependence symptoms×populations.

Circles denote the eight dependency domains and triangles denote the 12 study groups. The percentages indicate the amount of variance accounted for by principal components PC1 and PC2. Total explained variance from the first two components is 71%. Among the populations who chewed betel-quid, dependency domains were more correlated within the six south and south-east Asian samples, within the four east Asian samples and within the two Nepalese samples. These three groups are clustered in the first, second and fourth quadrants respectively. Domains ‘craving’ and ‘time spent chewing’ were the most important dependency symptoms for Sri Lankan, Malaysian and Indonesian populations and for Taiwan and Hunan populations respectively. In contrast, the more biological domains of dependence, ‘tolerance’ and ‘withdrawal’, were the major dependency symptoms for Nepalese populations.

Betel-quid accessibility and prevention

Table 3 and online Tables DS2 and DS3 present an assessment of betel-quid approachability factors, including environmental accessibility and preventive activities. We found that all communities had features of easy availability, low price and ready-made packaging of betel-quid. Attractive and misleading advertisements for betel-quid were also observed in Hunan, and aggressive marketing of betel-quid products was active in Nepal. For preventive activities, several bans have been launched in Taiwan, such as prohibitions on spitting betel juice in the street and on the cultivation of areca nut palms. In Taiwan and Nepal, statutory warnings about the detrimental aspects of chewing are inscribed on betel-quid packets. Betel-quid was most easily available in the Hunan and Nepal communities (having six and five positive factors respectively), and no preventive activity existed in Hunan, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Prevalence and risk of OPMD

Table 4 shows the population prevalence and risks of OPMD categorised according to betel-quid use. Except in Malaysia, OPMD prevalence was higher in the dependent group (0.9–31.2%) than in the non-dependent user group (0.0–16.6%). Compared with non-users, dependent participants had a greater OPMD risk (adjusted OR 2.5–51.5) than the non-dependent chewer group (adjusted OR 5.6–39.1). Using combined data from the six Asian populations, we evaluated the effect of the degree of betel-quid dependency on OPMD (Table 5). The prevalence of OPMD increased with the number of DSM-IV and ICD-10 dependence domains (both P for trend <0.001). Overall, among participants who chewed betel-quid, those with five to seven DSM-IV domains had a 28- to 51-fold OPMD prevalence risk, whereas those with five or six ICD-10 domains had a 23-fold risk.

Discussion

Areca nuts have been chemically verified to contain several polyphenols (flavonols and tannins) and alkaloids (arecoline, arecaidine, guvacine and guvacoline) that possess stimulant and psychoactive effects. 6 By raising adrenaline or noradrenaline levels, with the modulation of cholinergic and monoamine transmission, areca nut compounds exert neurobiological influences on the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Reference Winstock21–Reference Chen, Tu, Wang, Ko, Lee and Chiang23 In human studies, prolonged use of betel-quid has been reported to cause tolerance and withdrawal syndromes (two central biological modules of dependence syndromes). Reference Benegal, Rajkumar and Muralidharan24,Reference Bhat, Blank, Balster and Nichter25 Furthermore, among inhabitants of Papua New Guinea, areca nut psychosis was observed after sudden cessation of heavy betal-quid use. 6 Among south-east Asian emigrants addicted to betel-quid, the substance has been persistently consumed even after migration to Western countries. Reference Pickwell, Schimelpfening and Palinkas26 The ‘betel-mania’ phenomenon found among emigrant chewers has been associated with the import of betel-quid into ethnic enclaves. Reference Pickwell, Schimelpfening and Palinkas26 In this study we found that betel-quid dependency (DSM-IV prevalence 7.7–43.5%) in specific groups, such as Hunan men, Malaysian women, and Indonesian and Nepalese samples, exceeded the reference DSM-IV prevalence of alcohol dependence reported in several national surveys worldwide (1.2–4.4%). Reference Teesson, Hall, Slade, Mills, Grove and Mewton27

TABLE 2 Adjusted odds ratios of non-dependent chewing and dependent chewing associated with demographic and chewing characteristics

| Taiwan | Mainland China | Malaysia | Indonesia | Sri Lanka | NepalFootnote a | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDC v.

NC aORFootnote b (95% CI) |

DC v.

NC aORFootnote b (95% CI) |

DC v.

NC ORFootnote b ratio |

NDC v.

NC aORFootnote b (95% CI) |

DC v.

NC aORFootnote b (95% CI) |

DC v.

NC ORFootnote b ratio |

NDC v.

NC aORFootnote b (95% CI) |

DC v.

NC aORFootnote b (95% CI) |

DC v.

NC ORFootnote b ratio |

NDC v.

NC aORFootnote b (95% CI) |

DC v.

NC aORFootnote b (95% CI) |

DC v.

NC ORFootnote b ratio |

NDC v.

NC aORFootnote b (95% CI) |

DC v.

NC aORFootnote b (95% CI) |

DC v.

NC ORFootnote b ratio |

DC v.

NC aORFootnote b (95% CI) |

|

|

Demographic factors

Gender (male/female) |

2.3 (0.9–5.4) | 1.9 (0.7–5.6) | 0.9 | 5.7 (3.4–9.7) | 8.1 (3.1–21.1) | 1.4 | 0.1 (0.1–0.3) | 0.1 (0.03–0.3) | 0.8 | 0.6 (0.2–1.4) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 0.9 | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 1.6 (0.6–3.9) | 1.4 | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) |

| Age, years | ||||||||||||||||

| 31-40/⩽30 | 2.6 (0.7-9.9) | 1.3 (0.3-5.7) | 0.5 | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 0.7 (0.4-1.2) | 0.8 | 4.3 (1.8-10.6) | 3.5 (0.3-40.3) | 0.8 | 2.9 (0.9-8.4) | 3.4 (0.9-12.4) | 1.2 | 2.2 (0.9-5.3) | 8.9 (1.1-73.9) | 4.1 | 0.7 (0.4-1.4) |

| 41-50/⩽30 | 3.1 (0.9-11.4) | 1.6 (0.3-7.4) | 0.5 | 0.4 (0.3-0.7) | 0.4 (0.2-0.8) | 1.0 | 5.6 (2.4-13.4) | 34.0 (4.2-277.4) | 6.0 | 7.5 (2.7-21.2) | 8.8 (2.5-31.4) | 1.2 | 3.9 (1.7-9.1) | 20.3 (2.4-174.3) | 5.2 | 1.0 (0.5-2.1) |

| ⩾51/⩽30 | 1.9 (0.5-7.0) | 1.5 (0.4-6.2) | 0.8 | 0.2 (0.1-0.3) | 0.1 (0.03-0.2) | 0.4 | 10.6 (4.4-25.4) | 59.9 (7.6-469.9) | 5.7 | 19.6 (8.6-44.7) | 28.5 (8.0-101.5) | 1.5 | 5.4 (2.5-11.6) | 14.9 (1.9-119.0) | 2.7 | 1.1 (0.4-2.8) |

| P for trend | 0.304 | 0.472 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 | 0.925 | |||||

| Schooling, years | ||||||||||||||||

| 7-9/⩾10 | 2.8 (1.4-5.5) | 2.1 (0.6-6.7) | 0.7 | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) | 0.9 | 1.7-0.7-4.1) | 10.0 (1.1-93.2) | 5.9 | 1.3 (0.2-7.3) | 2.0 (0.7-5.2) | 1.5 | 2.3 (1.3-4.0) | 5.9 (1.5-22.5) | 2.6 | 2.5 (0.9-6.7) |

| ⩽6/⩾10 | 3.4 (1.4-8.3) | 3.1 (1.1-8.5) | 0.9 | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) | 0.9 (0.4-1.8) | 1.3 | 4.4 (2.0-9.8) | 27.2 (3.4-217.5) | 6.1 | 0.9 (0.2-4.0) | 3.0 (0.9-9.3) | 3.6 | 4.8 (2.6-8.7) | 25.6 (6.9-94.7) | 5.4Footnote * | 1.8 (0.9-3.4) |

| P for trend | 0.006 | 0.028 | 0.065 | 0.395 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.493 | 0.064 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.265 | |||||

| Substance use factors

Drinking alcohol (yes/no) |

6.2 (3.3-11.6) | 4.1 (1.6-10.5) | 0.7 | 2.5 (1.8-3.4) | 2.1 (1.3-3.5) | 0.9 | 3.0 (1.2-7.3) | 9.4 (3.1-28.4) | 3.1 | 0.5 (0.2-1.6) | 0.3 (0.2-0.5) | 0.6 | 1.6 (0.8-3.3) | 4.7 (1.4-16.0) | 3.0 | 12.7 (6.6-24.5) |

| Smoking tobacco

(yes/no) |

3.9 (1.8-8.4) | 3.8 (1.3-10.7) | 1.0 | 3.7 (2.6-5.3) | 5.0 (2.9-8.9) | 1.4 | 0.5 (0.2-1.2) | 0.3 (0.1-0.7) | 0.5 | 0.1 (0.04-0.3) | 0.04 (0.03-0.1) | 0.4 | 1.4 (0.7-3.0) | 0.3 (0.1-1.3) | 0.2Footnote * | 0.8 (0.5-1.5) |

| BQ chewing factors, ORFootnote c | ||||||||||||||||

| Starting age, yearsFootnote d | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||||||||

| Amount, quids/dayFootnote d | 1.0 | 1.1Footnote * | 1.3Footnote * | 1.3Footnote * | 1.5Footnote * | |||||||||||

| Frequency,

days/weekFootnote d |

1.7Footnote * | 1.4Footnote * | 1.8Footnote * | 1.7Footnote * | 1.5Footnote * | |||||||||||

| Type, TA-BQ/TF-BQFootnote d | NA | NA | 1.3 | 0.5 | 5.8Footnote * | |||||||||||

| BQ family history

(yes/no) |

1.0 | 2.6Footnote * | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.6 | |||||||||||

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; BQ, betel-quid; DC, dependent chewers; NA, non-appreciable (owing to all chewers consuming TF-BQ); NC, non-chewers; NDC, non-dependent chewers (dependence was defined by meeting DSM-IV or ICD-10 criteria); TA-BQ: tobacco-added BQ; TF-BQ: tobacco-free BQ.

a Because the overwhelming majority of chewers in Nepal were BQ-dependent, only ORs for DC are shown.

b Odds ratios and OR ratios were adjusted for all demographic factors, drinking alcohol and smoking tobacco.

c Data analysis was restricted to current chewers and NDC was the reference group.

d Factors were treated as a continuous variable.

* P<0.05.

TABLE 3 Environmental accessibility and preventive activities in regard to betel-quid use and the prevalence of dependence in six Asian communities

| Factors | Taiwan | Mainland China | Malaysia | Indonesia | Nepal | Sri Lanka |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental accessibility | ||||||

| Easy availability | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Low cost | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ready-made packaging | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Attractive packaging | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Aggressive marketing | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| BQ advertisement | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Misleading advertisement | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| No. of factors for favourable BQ accessibility | 4 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 |

| Preventive activity | ||||||

| BQ-related ban | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Statutory warning | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Health education awareness programmes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| No. of absent BQ usage prevention activities | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| BQ dependence prevalence, %Footnote a | 2.8 | 4.4 | 8.6 | 26.2 | 39.2 | 3.4 |

BQ, betel-quid.

a Defined as meeting either DSM-IV or ICD-10 BQ dependence criteria.

Individual-level factors related to dependence

In this survey, irrespective of the criteria used to define dependence, men dominated the betel-quid dependency prevalence among Taiwanese and mainland Chinese chewers and women dominated the prevalence in Malaysia and Indonesia. One previous study that examined factors affecting beginning and quitting chewing behaviours reported that Malaysian women are more likely to start and less likely to stop the chewing habit. Reference Ghani, Razak, Yang, Talib, Ikeda and Axell28 These results emphasise that women who chew betel-quid should not be overlooked. In contrast to the social constraints imposed on tobacco and alcohol consumption, betel-quid chewing is publicly accepted, including use by women. Reference Strickland29 Within certain Asian communities cigarette smoking is considered a male prerogative and betel-quid chewing a female habit, and women have learned the use of this substance primarily from their mothers and grandmothers. Reference Pickwell, Schimelpfening and Palinkas26

Among Hunan men the youngest age group was most affected by betel-quid dependency. Hunan is a southern province of China where betel-quid chewing is becoming prevalent. Reference Tang, Jian, Gao, Ling and Zhang30 There, betel-quid is consumed in dried husks of the areca fruit marinated with diverse flavoured ingredients. This style differs from usage patterns in other populations. Recent economic growth and heavier advertising have enhanced the popularity of betel-quid chewing in Hunan. One study showed that since the 1980s the number of those chewing has increased substantially. Reference Zhang and Reichart31 Young people have adopted this substance in its mint, cinnamon and orange flavours. Because China's betel-quid manufacturers and workshops have congregated in Xiangtan City in Hunan, Reference Zhang and Reichart31 easy availability, low price, attractive packaging and the lack of health risk warnings have formed the macro-environment that facilitates the development of dependency among those chewing betel-quid.

We found that countries have diverse domain-level symptoms of betel-quid dependency. In Taiwan and Hunan, spending considerable time chewing betel-quid was the central indicator endorsed by men, and blue-collar workers were the major users. Because betel-quid chewing can help focus, keep users awake, heighten alertness and increase capacity for work, Reference Winstock21,Reference Chu32 workers who chronically consumed betel-quid probably sought these pharmacological effects. Reference Ko, Chiang, Chang and Hsieh33 We also observed that all Nepalese chewers used tobacco-added betel-quid, and relative to the other samples clustered more with ‘tolerance’ and ‘withdrawal’ symptoms (the more biology-associated domains of dependence). Preceding studies have demonstrated that nicotine-containing betel-quid is an addictive admixture that is likely to predispose people to dependent use of these substances. Reference Benegal, Rajkumar and Muralidharan24 In Malaysia, Indonesia and Sri Lanka, ‘craving’ was the most common domain endorsed by participants with any betel-quid dependency. This suggests craving as a critical component for measuring betel-quid dependent use in south-east and south Asian communities. Because craving appears in ICD-10 but not in DSM-IV criteria, the DSM-5 working group incorporated craving into the new diagnostic schema for a substance use disorder. Reference O'Brien34 In a recent investigation conducted to determine whether craving fits with or improves the DSM-IV criteria set for alcohol use disorders, the inclusion of craving with the existing criteria better distinguished people with and without alcohol problems. Reference Keyes, Krueger, Grant and Hasin35

A linear trend towards increased risk of betel-quid dependency with less schooling was observed for both men and women in Taiwan, Malaysia and Sri Lanka. This presents a challenging task for health education against betel-quid use because of its pervasive culture-derived features and favourable pharmacological effects. Some ethnic groups even treat betel-quid as an innocuous substance like coffee or tea. Reference Bhat, Blank, Balster and Nichter25 In one recent Sri Lankan survey, 76% of participants, primarily from lower socioeconomic groups, were unaware of any ill effects from areca nut use. Reference Amarasinghe, Usgodaarachchi, Johnson, Lalloo and Warnakulasuriya36 In Indian communities, people were aware of higher cancer risks for gutka and tobacco use. However, awareness of detrimental health risks from betel-quid chewing remains limited. Reference Gunaseelan, Sankaralingam, Ramesh and Datta37

Alcohol drinking is a concomitant habit with betel-quid use in several cultures. Reference Lee, Ko, Warnakulasuriya, Yin, Sunarjo and Zain1 We found that those who drank alcohol were more likely to be dependent on betel-quid in Taiwan, mainland China, Malaysia, Nepal and Sri Lanka (adjusted OR 2.1–12.7). Tobacco smoking was also found to predict betel-quid dependent use (adjusted OR 3.8–5.0) in the two Chinese populations. However, in Malaysia and Indonesia, where tobacco-added betel-quid is commonly used, smoking was associated with a lower probability of betel-quid dependency. Because tobacco-added betel-quid chewing was inversely correlated with tobacco smoking (r = –0.17 and –0.57 for Malaysia and Indonesia respectively; both P<0.001), such betel-quid consumption may competitively diminish tobacco smoking in betel-quid dependency.

Chewing quantity and frequency were found to be the most significant factors for dependency, which was also observed in one Indian study as the chewing characteristics that contributed substantially to the DSM-IV criteria for areca nut dependence. Reference Benegal, Rajkumar and Muralidharan24 For our Sri Lankan sample, using tobacco-added betel-quid conferred a higher risk of dependency than using tobacco-free mixtures. Such findings have been replicated Reference Benegal, Rajkumar and Muralidharan24 and suggest that the addictive ingredient of tobacco (i.e. nicotine) may increase dependence on tobacco-added products. In Hunan, a family history of betel-quid use was another predictor of dependence. A previous study indicated that the father and grandfather are the most influential family members for inducing the first chewing habit in an adolescent. Reference Lu, Lan, Hsieh, Yang, Ko and Tsai38 Family-based preventive programmes may be an effective approach to reducing betel-quid dependency in Hunan.

TABLE 4 Prevalence and odds ratios of oral potentially malignant disorders associated with divergent degree of betel-quid use

| Oral lichen planus | Oral submucous fibrosis | Oral leukoplakia | OPMD | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size, n | Prevalence, % | ORFootnote a | Prevalence, % | ORFootnote a | Prevalence, % | ORFootnote a | Prevalence, % | ORFootnote a | |||||||||||||||

| NC | NDC | DC | NC | NDC | DC | NDC v. NC |

DC v. NC |

NC | NDC | DC | NDC v. NC |

DC v. NC |

NC | NDC | DC | NDC v. NC |

DC v. NC |

NC | NDC | DC | NDC v. NC |

DC v. NC |

|

| Taiwan | 1300 | 38 | 29 | 0.1 | 6.5 | 6.4 | 60.5Footnote * | 70.4Footnote * | 0.0 | 6.5 | 11.4 | 7.6Footnote b | 46.5Footnote * Footnote b | 0.03 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 20.0Footnote * | 26.7Footnote * | 0.1 | 10.4 | 11.4 | 39.1Footnote * | 51.5Footnote * |

| China | 1991 | 199 | 98 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.1 | NA | 18.3Footnote * | 0.05 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 138.5Footnote * | 186.0Footnote * | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 13.1 | NA | 0.2 | 4.5 | 7.0 | 30.2Footnote * | 47.8Footnote * |

| Malaysia | 682 | 156 | 140 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA |

| Indonesia | 995 | 76 | 748 | 4.3 | 17.3 | 15.5 | 12.8Footnote * | 12.4Footnote * | 3.4 | 3.2 | 9.5 | 1.5 | 5.0Footnote * | 6.0 | 2.7 | 19.0 | 1.5 | 16.5Footnote * | 10.4 | 16.6 | 31.2 | 5.6Footnote * | 16.2Footnote * |

| Nepal | 624 | 4 | 374 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.9 | NA | 4.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.9 | NA | 2.5 |

| Sri Lanka | 854 | 151 | 38 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA | 0.03 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NA | NA | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 | NA | 2.0b | 0.03 | 0.0 | 2.0 | NA | 22.6Footnote * |

DC, dependent chewers (defined as meeting either DSM-IV or ICD-10 criteria); NA, non-appreciable; NC, non-chewers; NDC, non-dependent chewers; OPMD, oral potentially malignant disorders.

a Odds ratios adjusted for gender, age, alcohol drinking and tobacco smoking.

b Odds ratios calculated using the median unbiased estimates with the aid of exact logistic regression.

* P<0.05.

Environmental factors and dependency

Environmental access to betel-quid is a sociological concern. A report from India showed that betel-quid availability in a person's surroundings is closely associated with its use. Reference Chaturvedi39 In this study we observed five environmental promotion factors, such as aggressive marketing of betel-quid products in Nepalese communities. All Nepalese chewers were found to be users of tobacco-added products. The greater addictive properties of tobacco-added betel-quid, combined with its easy availability, may partially explain the high prevalence of betel-quid dependency (39%) observed in Nepal.

In campaigns against chewing, the Taiwan government designated 3 December as Betel Quid Prevention Day, alluding to the 123-fold increase in oral cancer risk for betel-quid chewers who concurrently consumed alcohol and cigarettes. Reference Ko, Huang, Lee, Chen, Lin and Tsai12 The outcome of the campaigns was a 21% reduction in betel-quid production in 2010 (130 000 tonnes) relative to the year 2000 peak (165 000 tonnes). 40 These actions explain the lower prevalence of betel-quid dependency found in Taiwan. However, in places where such health promotions do not yet exist, such as Hunan, betel-quid is widely marketed on television as a safe mouth freshener. In recent years, betel-quid has become one of the most important local industries, with an annual gross economic value approaching US$1.18 billion. If current trends continue unabated, the availability of betel-quid will create a new generation of chewers among young people. Reference Lee, Ko, Warnakulasuriya, Yin, Sunarjo and Zain1

Betel-quid dependency and OPMD

Most authorities agree that OPMD prevalence ranges from 1% to 5%, according to geographic region, population characteristics and patterns of substance use. Reference Napier and Speight41 The annual proportion of OPMD that develops into oral squamous cell carcinoma remains undetermined, but the current best estimates are <0.1% for oral lichen planus, 0.5% for oral submucous fibrosis and 1% for oral leukoplakia. Reference Van der Waal42 Evidence from previous studies shows that oral submucous fibrosis is a disorder not limited to the oral cavity; it may extend beyond the mouth to the oesophagus (66% of patients with oral submucous fibrosis show histological abnormalities in the oesophagus). Reference Misra, Misra, Dwivedi and Gupta43 Consistent with the IARC report, 6 we observed that people who chewed betel-quid had high prevalence rates of OPMD, especially if they were dependent users. In area-combined data, dependency levels and OPMD risk demonstrated dose–effect findings, regardless of the criteria used. Despite progress in molecular biology, no single biomarker has been identified to predict OPMD malignant transformations. Reference Van der Waal42 Our results showed that the risk of OPMD in participants with non-dependent betel-quid use (0–2 dependency domains) was 4.5–5.9 times greater than in the non-chewers group, increasing to 8.0–51.3 among those with dependency. These findings disclose the significance of considering people with betel-quid dependency as an important screening target in the prevention and control of OPMD, and stress that those whose betel-quid use is non-dependent should not be neglected in oral examination programmes.

TABLE 5 Prevalence and adjusted odds ratios of oral potentially malignant disorders associated with the number satisfying DSM-IV and ICD-10 domains for betel-quid dependence: combined results from six Asian populations

| Sample size, n | Prevalence of OPMD, % | ORFootnote a (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-chewers | 6451 | 4.3 | 1.0 (reference) |

| Current chewers | |||

| No. of DSM-IV domains | |||

| 0-2 (non-dependence) | 704 | 7.3 | 5.9 (2.8-12.7) |

| 3-4 | 1040 | 16.9 | 8.0 (4.5-14.3) |

| 5-6 | 280 | 42.4 | 27.5 (10.8-69.6) |

| 7 | 36 | 47.8 | 51.3 (16.5-159.9) |

| P for linear trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| No. of ICD-10 domains | |||

| 0-2 (non-dependence) | 872 | 7.3 | 4.5 (2.4-8.6) |

| 3-4 | 966 | 31.3 | 20.5 (8.7-48.2) |

| 5-6 | 222 | 33.9 | 23.0 (11.0-48.2) |

| P for linear trend | <0.001 | <0.001 |

OPMD, oral potentially malignant disorders (including oral lichen planus, oral submucous fibrosis and oral leukoplakia).

a Adjusted for gender, age, alcohol drinking, tobacco smoking and study population.

Strengths and limitations

Because betel-quid chewing was publicly accepted in all groups in the study, participants were comfortable revealing their usage; therefore, this may have diminished underreporting of the extent of betel-quid dependent use. Because of the cross-sectional nature of the results, our study presents only a snapshot of betel-quid dependency for the study populations. Furthermore, chewing practices and ingredients diverge by area. The findings in this survey should not be generalised to other areas within the respective countries. However, the research methodology and network might be extended to countries where betel-quid usage is common, such as Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam.

Implications

This study draws immediate attention to the population-level psychiatric problems of betel-quid chewing in six Asian communities where it is widely consumed. The findings disclose the role of sociodemographic factors, other substance use and environmental approachability in betel-quid dependency, and its health impact on OPMD. An understanding of these factors can facilitate implementation of health promotion measures and the adequate management of the OPMD burden resulting from betel-quid chewing.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Centre of Excellence for Environmental Medicine, Kaohsiung Medical University (KMU-EM-99-1-1), and the Taiwan National Science Council (NSC 99-2314-B-037-057-MY3).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jennifer Ko, and the staff of the Centre of Excellence for Environmental Medicine, for their great assistance in helping to organise the various centres’ principal investigators.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.