Allopurinol is a xanthine oxidase inhibitor, approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the clinical management of gout and hyperuricaemia, decreasing uric acid levels by preventing purine degradation. Reference Pacher, Nivorozhkin and Szabo1 Its use has been proposed in treatment-resistant mania associated with hyperuricaemia, Reference Machado-Vieira, Lara, Souza and Kapczinski2 since uric acid – the end-product of purine metabolism – seems involved in the regulation of mood, sleep, appetite, social interaction and impulsivity. Reference Ortiz, Ulrich, Zarate and Machado-Vieira3 It has been proposed that bipolar affective disorder might be associated with a purinergic system dysfunction, Reference Machado-Vieira, Lara, Souza and Kapczinski4 showing, particularly in the manic phases of the illness, higher levels of plasma uric acid than those in both healthy people, Reference Salvadore, Viale, Luckenbaugh, Zanatto, Portela and Souza5 and in people affected by other mental disorders. Reference Albert, De Cori, Aguglia, Barbaro, Bogetto and Maina6 In addition, uric acid levels in manic phases seem significantly higher than in euthymic or depressive ones, Reference De Berardis, Conti, Campanella, Carano, Di Giuseppe and Valchera7,Reference Muti, Del Grande, Musetti, Marazziti, Turri and Cirronis8 and hyperthymic and depressive temperaments have been related respectively to high and low levels of uric acid. Reference Kesebir, Tatldil Yaylac, Suner and Gultekin9 Finally, lithium, one of the most effective medications for treating bipolar disorders, Reference Alda10 was originally studied as a therapeutic option by lowering the uric acid concentration in plasma. Reference Shorter11 In sum, there might be a plausible biological and clinical rationale for allopurinol use in treating symptoms of mania in people with bipolar disorder. A previous meta-analysis, Reference Hirota and Kishi12 testing purinergic modulators for the treatment of both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, investigated the effect of allopurinol on manic symptoms. However, methodological issues such as the lack of risk of bias and quality assessments, the heterogeneity of outcome measures chosen, the absence of appropriate subgroups and sensitivity analyses, as well as the limited sample size from available studies, made it impossible to draw firm conclusions. In addition, two recently published trials have shown mixed results. Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13,Reference Weiser, Burshtein, Gershon, Marian, Vlad and Grecu14 Thus, a body of evidence of acceptable size has accumulated, possibly overcoming the limitations of previous research in exploring the efficacy and tolerability of allopurinol for treating people with bipolar disorder. Studying new treatments for bipolar disorder is important because a significant proportion of patients still fail to respond to standard therapeutic options with mood stabilisers and second-generation antipsychotics. Reference Ortiz, Ulrich, Zarate and Machado-Vieira3,Reference Sanches, Newberg and Soares15,Reference Zarate and Manji16 We report a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared efficacy and safety of adjunctive allopurinol against placebo, aiming to clarify its role in treating symptoms of mania in people with bipolar disorder.

Method

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman17 The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42015025120).

Eligibility criteria

We included RCTs that compared adjunctive allopurinol with placebo for the treatment of symptoms of mania, along with standard mood stabilisers and/or antipsychotic treatment. To be considered, studies had to recruit adults with bipolar disorder experiencing a manic or mixed episode, from any in-patient or out-patient setting.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was efficacy, as measured by mean overall change (from baseline to end-point) in mania symptoms assessed with any appropriate rating scale, including (but not limited to) the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS). Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer18 Secondary outcomes were remission, all-cause discontinuation and side-effects. Remission was defined as a score less than or equal to the standard cut-off of the chosen measure (12 on the YMRS total score). Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer18 All-cause discontinuation (acceptability) was estimated by calculating the number of participants who left the study early for any reason before reaching their end-point. Finally, we assessed differences in frequencies of side-effects occurring in 5% or more of individuals from at least two different studies.

Search strategy

Computerised PubMed, Cochrane Library and PsycINFO (via ProQuest) searches were performed from database inception until August 2015. We searched ClinicalTrials.gov (search date 19 August 2015) for all unpublished intervention studies. There was no language restriction. Index and free-text search terms included ‘allopurinol’ AND (‘bipolar’ OR ‘mania’ OR ‘manic’). Two authors (F.B. and G.C.) independently performed the preliminary screening based on titles and abstracts, to include potentially relevant articles. After the first screening, studies were retrieved in full text to check eligibility according to inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction

We developed a sheet for the extraction of the main information from each included study: year of publication, study location, setting, inclusion criteria, sample size, participants' characteristics, tested allopurinol dose and standard treatment, follow-up duration and main results. Two authors (F.B. and G.C.) independently conducted data extraction, and discordances were resolved by consensus with the co-authors (C.C. and M.C.). When reported information was unclear or ambiguous, the relevant corresponding author was contacted (by F.B.) for clarification.

Risk of bias and quality of evidence

We followed the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) for grading the quality of evidence as high, moderate, low or very low, according to the standard items. Reference Schunemann, Oxman, Vist, Higgins, Deeks, Glasziou, Higgins and Green19 We used the standard Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting and other biases. Reference Higgins, Altman, Gotzsche, Juni, Moher and Oxman20 Selection bias was assessed by evaluating the appropriateness of random sequence generation and allocation concealment. Performance and detection bias were evaluated by checking whether masking of participants/personnel and outcome assessors respectively was guaranteed. Attrition bias was ascertained assessing proportions and balance of withdrawals from the trial between groups leading to incomplete outcome data, and strategies implemented to deal with this issue. We considered at low risk of bias studies with attrition rates of 20% or below in either study arm, Reference Dumville, Torgerson and Hewitt21 or those using full (‘as randomised’) or modified (excluding only randomised participants dropping out before receiving treatment) intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses for primary outcome. Reference Gupta22 Reporting bias was evaluated by checking first that data on key outcomes – efficacy, discontinuation rates and side-effects – were provided, and second that a previously registered study protocol with sufficient agreement with the final manuscript was available. Finally, to classify studies for ‘other biases’, we considered authors' potential conflicts of interest and potential sources of indirectness, Reference Schunemann, Oxman, Vist, Higgins, Deeks, Glasziou, Higgins and Green19 taking into account whether standard treatment for bipolar disorder was comparable between allopurinol and control groups or whether further treatment differences, potentially influencing clinical response, could be identified. Two authors (F.B. and G.C.) independently assessed the risk of bias. Differences in the evaluation were resolved by consensus with the other authors (C.C. and M.C.). Graphical summaries of risk of bias were created using RevMan version 5.2.

Statistical analysis

For the primary outcome (efficacy) we used either mean overall change (from baseline to end-point in both allopurinol and placebo groups) on mania symptom scores (with standard deviations or standard errors) or relevant t-test values, to estimate standardised mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals. Individual SMDs were pooled in a meta-analysis by the inverse variance method using random effects models. Intention-to-treat data, with last observation carried forward (LOCF) analyses, were used. A subgroup analysis was carried out to explore whether studies selecting people with manic episodes and those including also people with mixed episodes showed different effect sizes. We used the I 2 test for subgroup differences to assess the variability in effect estimates that was due to genuine differences rather than chance. Reference Deeks, Higgins, Altman, Higgins and Green23 In addition, we used meta-regression to test potential differences across studies due to other characteristics, including follow-up duration (4 weeks v. longer), allopurinol dosage (300 mg/day v. different dosages) and standard treatment for bipolar disorder (lithium v. other treatments), using the Monte Carlo permutation test for meta-regression with moment-based estimate of between-study variance. Finally, a sensitivity analysis was performed omitting the studies with high or unclear risk of bias on selected items (selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting and other bias).

For secondary outcomes (remission, discontinuation and side-effects) rates between allopurinol and placebo groups were compared using random effects risk ratio (RR). Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 and results were summarised using conventional forest plots. Heterogeneity was estimated using both P values from Cochran's Q-test and the I 2 index, with values of 25%, 50% and 75% taken to indicate low, moderate and high levels of heterogeneity respectively. Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman24 Finally, testing for publication bias, we used Egger's test if at least ten studies were included in the meta-analysis, as recommended. Reference Sterne, Egger, Moher, Higgins and Green25 Analyses were performed using Stata statistical software package version 13.1.

Results

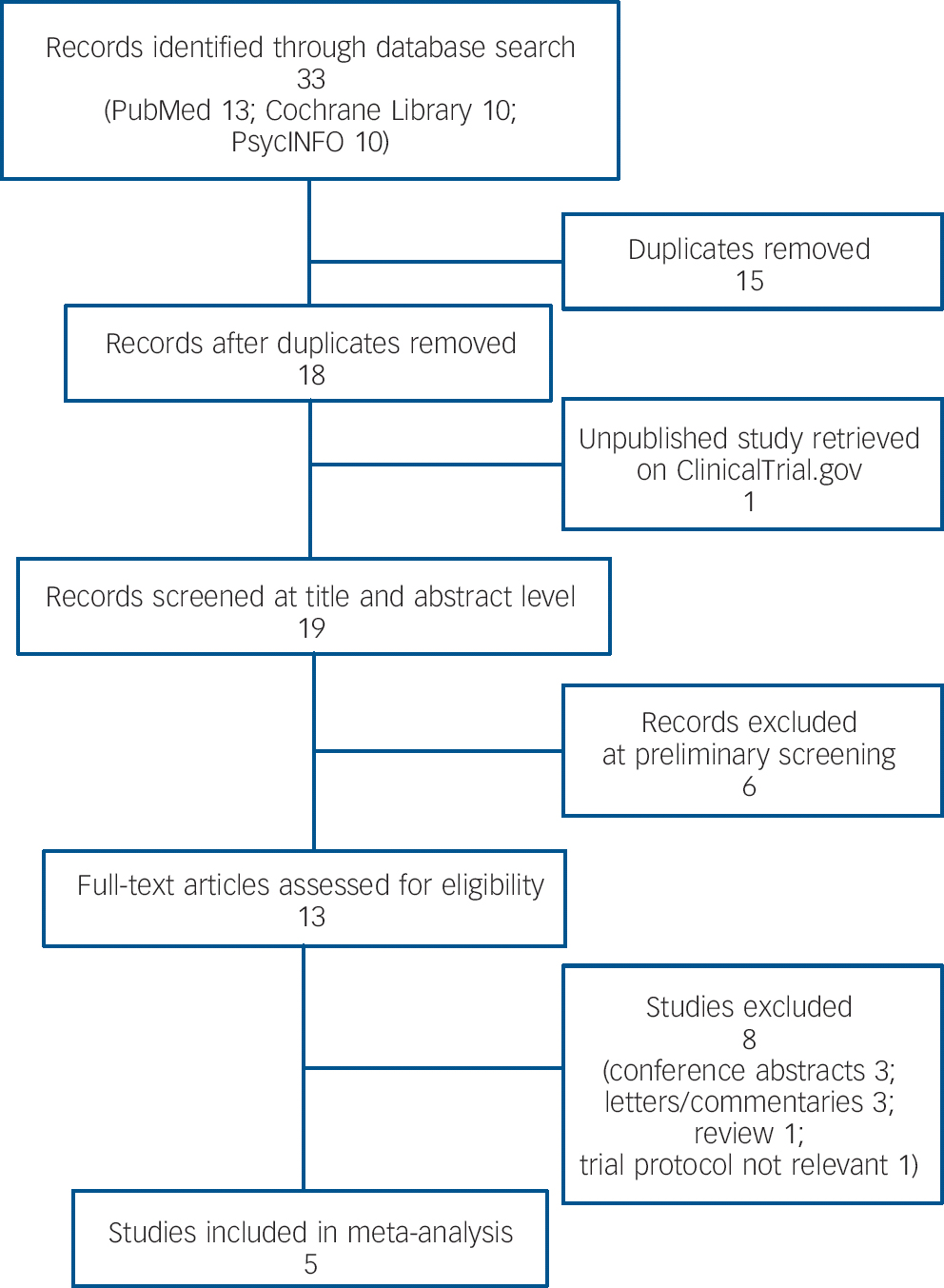

Our search generated 13, 10 and 10 records from PubMed, Cochrane Library and PsycINFO (via ProQuest) respectively. After removing duplicates and including one additional record from ClinicalTrials.gov, there were 19 studies to be screened (Fig. 1). The preliminary screening by reading titles and/or abstracts identified 13 potentially eligible studies. After screening full texts we excluded eight studies: three conference abstracts, three letters or commentaries, one review and a trial protocol on allopurinol augmentation for prevention of mania that was not relevant. Five RCTs met our inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13,Reference Weiser, Burshtein, Gershon, Marian, Vlad and Grecu14,Reference Akhondzadeh, Milajerdi, Amini and Tehrani-Doost26–Reference Machado-Vieira, Soares, Lara, Luckenbaugh, Busnello and Marca28 All manuscripts were written in English. The studies, published between 2006 and 2014, were based on in-patient and/or out-patient samples, and were from Iran, Brazil, Romania and the USA. All studies used the YMRS to measure symptoms. Duration of follow-up ranged between 4 weeks and 8 weeks. Detailed characteristics of included studies are summarised in online Table DS1. We obtained unpublished data from two studies, Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13,Reference Machado-Vieira, Soares, Lara, Luckenbaugh, Busnello and Marca28 contacting relevant corresponding authors who provided information on YMRS mean changes (with standard deviations) in both allopurinol and placebo groups, Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13,Reference Machado-Vieira, Soares, Lara, Luckenbaugh, Busnello and Marca28 as well as remission rates based on the YMRS standard cut-off score of 12. Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13

Fig. 1 Study selection.

Risk of bias

Graphical assessments of the risk of bias are reported in online Figs DS1 and DS2.

Selection bias

Two studies clearly described appropriate methods for random sequence generation, with a computer-based number generator, Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13,Reference Akhondzadeh, Milajerdi, Amini and Tehrani-Doost26 whereas in the other studies methods were unclear. Reference Weiser, Burshtein, Gershon, Marian, Vlad and Grecu14,Reference Fan, Berg, Bresee, Glassman and Rapaport27,Reference Machado-Vieira, Soares, Lara, Luckenbaugh, Busnello and Marca28 Appropriate methods for allocation concealment were described in all studies but one, which provided no information on allocation method. Reference Fan, Berg, Bresee, Glassman and Rapaport27

Performance and detection bias

All studies were double-blind RCTs and blinding (masking) of participants and personnel, as well as of outcome assessors, was satisfactorily guaranteed with low risk of performance or detection bias.

Attrition bias

All studies adopted approaches to dealing with attrition bias, using ITT data and including LOCF of people who left the study. Two studies used a full ITT approach, taking into account for primary analyses all randomised participants. Reference Weiser, Burshtein, Gershon, Marian, Vlad and Grecu14,Reference Akhondzadeh, Milajerdi, Amini and Tehrani-Doost26 Two other studies used modified ITT, excluding from primary outcome analyses randomised individuals withdrawing before participating in any of the study stages. Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13,Reference Fan, Berg, Bresee, Glassman and Rapaport27 However, one study might have been influenced by some degree of attrition bias since it did not use a proper ITT approach, excluding from primary outcome analyses a high proportion of randomised participants (25% and 23% of those on allopurinol and placebo respectively) who discontinued the intervention early. Reference Machado-Vieira, Soares, Lara, Luckenbaugh, Busnello and Marca28

Reporting bias

Three studies provided complete data on key outcomes, Reference Weiser, Burshtein, Gershon, Marian, Vlad and Grecu14,Reference Akhondzadeh, Milajerdi, Amini and Tehrani-Doost26,Reference Machado-Vieira, Soares, Lara, Luckenbaugh, Busnello and Marca28 whereas two studies did not report clear and detailed findings on frequency of different side-effects occurring among the allopurinol and placebo groups respectively. Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13,Reference Fan, Berg, Bresee, Glassman and Rapaport27 However, among studies with complete data, one study did not have a protocol, Reference Akhondzadeh, Milajerdi, Amini and Tehrani-Doost26 whereas another had a protocol registered after the study completion. Reference Machado-Vieira, Soares, Lara, Luckenbaugh, Busnello and Marca28 Only one study had a protocol with sufficient agreement with the final manuscript; Reference Weiser, Burshtein, Gershon, Marian, Vlad and Grecu14 all the other studies were therefore judged as being at high or unclear risk of reporting bias.

Other bias

One study reported some potential conflict of interest, Reference Fan, Berg, Bresee, Glassman and Rapaport27 whereas the others did not disclose any financial influence. Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13,Reference Weiser, Burshtein, Gershon, Marian, Vlad and Grecu14,Reference Akhondzadeh, Milajerdi, Amini and Tehrani-Doost26,Reference Machado-Vieira, Soares, Lara, Luckenbaugh, Busnello and Marca28 Furthermore, three studies used identical (or convincingly comparable) standard treatments for bipolar disorder in both allopurinol and placebo arms, i.e. 1–1.2 mEq/L lithium plus 10 mg haloperidol, Reference Akhondzadeh, Milajerdi, Amini and Tehrani-Doost26 flexible doses of lithium according to relevant plasma levels, Reference Machado-Vieira, Soares, Lara, Luckenbaugh, Busnello and Marca28 and 15–20 mg/kg of sodium valproate. Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13 On the other hand, potential indirectness bias in terms of comparability of standard treatments for bipolar disorder between allopurinol and control groups was found in two studies that included people treated with a wide range of psychopharmacological agents for bipolar disorder (unspecified and mixed mood stabilisers and/or atypical antipsychotics). Reference Weiser, Burshtein, Gershon, Marian, Vlad and Grecu14,Reference Fan, Berg, Bresee, Glassman and Rapaport27

Synthesis of results

The included studies screened for eligibility 679 participants, of whom 469 met inclusion criteria and were randomised to receive allopurinol (n = 236) or placebo (n = 233). An overall sample of 433 participants, 218 receiving allopurinol and 215 placebo, were analysed for the primary outcome. Among these, 364 participants, i.e. 78% of those randomised, completed the trials (184 from the allopurinol arms and 180 from the placebo arms).

Efficacy

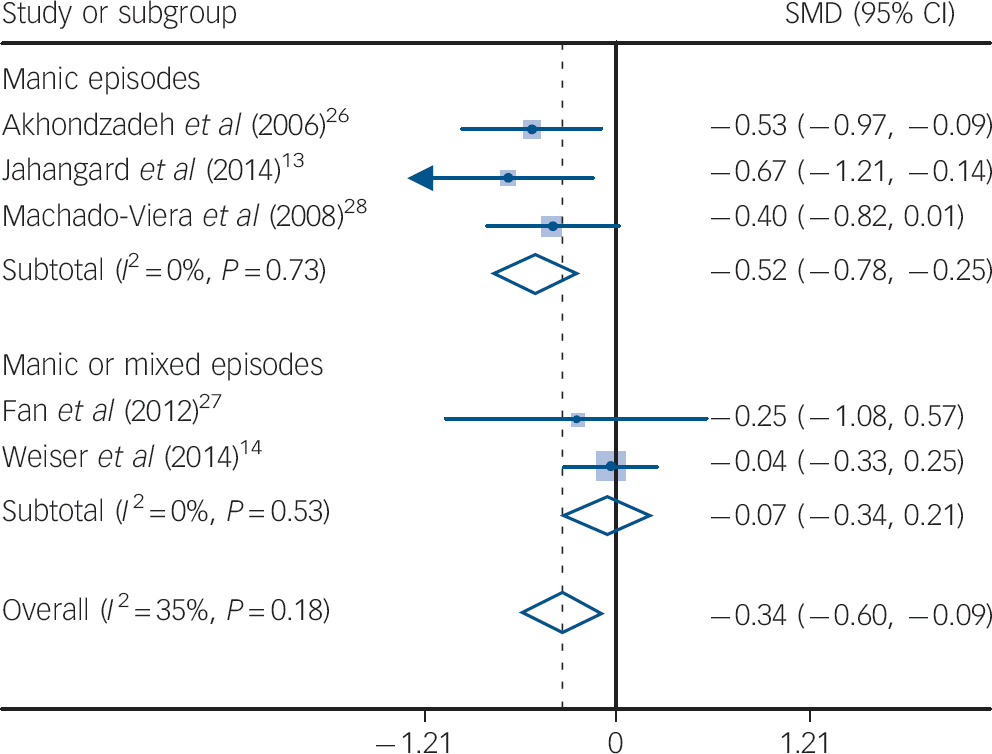

Decrease of mania symptoms (from baseline to end-point) as measured by the YMRS was significantly more marked among people taking allopurinol compared with those taking placebo (SMD = −0.34, 95% CI −0.60 to −0.09; P = 0.007). Heterogeneity was low to moderate (I 2 = 35%, P = 0.18), and subgroup analysis of studies restricted to people with manic episodes showed an effect of add-on allopurinol (P<0.001) that was not seen in studies including participants with mixed episodes (P = 0.64) (Fig. 2). The test for subgroup differences was significant (P = 0.02). According to the meta-regression analysis, allopurinol dosage (P = 0.50), follow-up duration (P = 0.41) and standard treatment chosen (P = 0.59) did not influence the results of the meta-analysis. Sensitivity analyses, omitting studies with high or unclear risk of bias on selected items, are reported in Table 1. Publication bias was not formally assessed, as fewer than ten studies were included in our review.

Table 1 Sensitivity analyses categorised by risk of bias

| Available studies a |

Allopurinol group n |

Placebo group n |

SMD (95% CI) | P | I 2, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk of selection bias due to random sequence generation | 2 | 71 | 68 | −0.59 (−0.93 to −0.25) | <0.001 | 0 |

| Low risk of selection bias due to allocation concealment | 4 | 206 | 204 | −0.36 (−0.66 to −0.07) | 0.015 | 51 |

| Low risk of attrition bias | 4 | 173 | 169 | −0.35 (−0.68 to −0.01) | 0.043 | 49 |

| Low risk of bias due to conflicts of interest | 4 | 206 | 204 | −0.36 (−0.66 to −0.07) | 0.015 | 51 |

| Low risk of bias due to heterogeneous treatment | 3 | 116 | 114 | −0.52 (−0.78 to −0.25) | <0.001 | 0 |

SMD, standardised mean difference.

Fig. 2 Change from baseline to end-point in symptoms of mania: standardised mean differences (SMD) for adjunctive allopurinol v. placebo.

a. Only one study had a low risk of reporting bias and all studies had low risks of performance and detection bias, thus no sensitivity analyses were carried out.

Remission

Data on remission were available from two studies, Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13,Reference Machado-Vieira, Soares, Lara, Luckenbaugh, Busnello and Marca28 accounting for 177 participants. The pooled RR of clinical remission was 1.51 (95% CI 1.20 to 1.90, P<0.001; I 2 = 0%) in people taking allopurinol compared with those taking placebo.

Discontinuation

Data on discontinuation were available for 469 participants (236 receiving allopurinol and 233 placebo). The meta-analysis showed no difference in all-cause discontinuation between allopurinol and placebo, with a RR of 0.91 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.26, P = 0.58) and no heterogeneity across studies (I 2 = 0%, P = 0.43).

Side-effects

Data on rates of side-effects were available in three of five included studies, Reference Weiser, Burshtein, Gershon, Marian, Vlad and Grecu14,Reference Akhondzadeh, Milajerdi, Amini and Tehrani-Doost26,Reference Machado-Vieira, Soares, Lara, Luckenbaugh, Busnello and Marca28 since others used continuous scores, Reference Fan, Berg, Bresee, Glassman and Rapaport27 or provided unclear information on differences in side-effect frequencies between index and control groups. Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13 Details of specific side-effects showed no difference in those more frequently observed, i.e. asthenia (P = 0.78), diarrhoea (P = 0.75), dizziness (P = 0.73), headache (P = 0.41) and somnolence (P = 0.59). No serious adverse event was reported. All detailed findings, with relevant effect sizes, included studies, sample sizes and heterogeneity, are summarised in online Table DS2.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis systematically evaluating data on efficacy and relevant secondary outcomes, as well as quality of evidence, of adjunctive allopurinol for treatment of symptoms of mania. Compared with previous meta-analyses, our review included two new, large RCTs, doubling the overall sample size. Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13,Reference Weiser, Burshtein, Gershon, Marian, Vlad and Grecu14 According to findings from five RCTs, adjunctive allopurinol in people with bipolar disorder showed higher efficacy in decreasing mania symptoms compared with placebo. The low to moderate statistical heterogeneity across studies added consistency to our findings. According to estimated SMD, we found a small to medium effect of add-on allopurinol. Reference Cohen29 The results were confirmed by relevant meta-regression analysis, highlighting that findings were not influenced or moderated by differences between studies in terms of allopurinol dosage, follow-up duration or standard treatment for bipolar disorder. Furthermore, we found that studies selecting people with a current manic episode showed a higher pooled effect size. Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13,Reference Akhondzadeh, Milajerdi, Amini and Tehrani-Doost26,Reference Machado-Vieira, Soares, Lara, Luckenbaugh, Busnello and Marca28 Relevant SMDs supported a medium effect for adjunctive allopurinol among individuals with manic episodes. Reference Cohen29 On the other hand, according to the relevant subgroup analysis, allopurinol did not show a significant effect in studies selecting also individuals with bipolar mixed features. Therefore, we can reasonably assume that adjunctive allopurinol could be an effective therapeutic option for people experiencing the most severe forms of bipolar disorder in terms of mania symptoms at baseline. Results for secondary outcomes – remission, discontinuation and tolerability – supported a potentially effective role for add-on allopurinol. Although data were available from only two studies, Reference Jahangard, Soroush, Haghighi, Ghaleiha, Bajoghli and Holsboer-Trachsler13,Reference Machado-Vieira, Soares, Lara, Luckenbaugh, Busnello and Marca28 we found a small but significant effect in terms of remission rates, with people taking allopurinol 1.5 times more likely to have remission of their symptoms compared with those taking placebo. Furthermore, allopurinol was not associated with treatment discontinuation, showing drop-out and all-cause discontinuation rates comparable with placebo. Finally, allopurinol seems a safe therapeutic option, as no significant risk of side-effects was found, even taking into account those more commonly reported, such as asthenia, diarrhoea, dizziness, headache and somnolence.

Quality of evidence and limitations

Despite early promising findings, evidence supporting adjunctive allopurinol for symptoms of mania should be considered at best ‘low’, following GRADE standard items. We uncovered at least two factors downgrading quality of evidence: first, although relevant sensitivity analyses confirmed the effect of allopurinol in decreasing mania symptoms, we found some important limitations, notably a potential risk of selective reporting among included studies. Second, reported effect sizes of outcomes, although consistent, were generally imprecise, with large confidence intervals, owing to the small sample size. A more conservative approach, considering both indirectness (due to non-comparable treatments found in two studies) and the uncertain probability of publication bias, would suggest further downgrading evidence to a ‘very low’ level. However, indirectness seemed to decrease rather than increase the effect size of allopurinol. Indeed, the relevant sensitivity analysis, excluding studies with heterogeneous treatments, showed a greater efficacy for allopurinol. Thus, we could be confident that the effect size of allopurinol was not inflated by an indirectness-related bias. Furthermore, it was impossible to assess statistical significance of publication bias, and we did not contact pharmaceutical companies or governing bodies involved in pharmaceutical market authorisation procedures to enquire whether any other RCTs had been undertaken with allopurinol given to participants with bipolar disorder. However, it seems unlikely that further RCTs in this field remained unpublished, since we searched three different electronic databases and comprehensively explored a trials register (ClinicalTrials.gov). Finally, even if we assume that studies not using full ITT analyses might have inflated positive reporting, this involved just one study. In sum, our findings should be interpreted with caution given both the small number of included RCTs meeting our inclusion criteria and the resulting limited overall sample size, as well as other reported quality issues.

Implications for practice and research

Adjunctive allopurinol shows a small to medium effect size on symptoms of mania in people with bipolar disorder. However, its effect, although statistically significant, seems small to be considered clinically meaningful. Taking into account standards developed to produce recommendations, evidence from this meta-analysis should be considered low in quality. Reference Schunemann, Oxman, Vist, Higgins, Deeks, Glasziou, Higgins and Green19 Nevertheless, owing to the significant effect of indirectness on results of this meta-analysis, further research with rigorously defined treatment patterns for both intervention and control groups is needed in order to confirm confidence in our findings. Allopurinol could be considered as a promising therapeutic option, in addition to standard treatment with mood stabilisers and/or second-generation antipsychotics, especially for the most severe forms of bipolar mania. Its efficacy seems clearer in studies including participants with manic episodes and excluding those with mixed episodes. Of course, before its benefits can be claimed, the relevant level of evidence should be improved and its efficacy and tolerability further explored in large multicentre RCTs, possibly based only on people with manic episodes. Moreover, since all available RCTs had short follow-up periods (4–8 weeks), long-term data are also needed in order to explore the safety of this drug and its potential role in maintenance treatment. Unfortunately, there is a lack of studies in this area, with only one research protocol with unknown results registered so far (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00732251). Furthermore, caution is needed also in interpreting results on tolerability of allopurinol, since this was assessed only during the acute treatment phase (with a maximum follow-up of 8 weeks), whereas the long-term safety in people with bipolar disorder remains unknown. In addition, allopurinol adverse effects could be more severe in people with bipolar disorder, Reference Seth, Kydd, Buchbinder, Bombardier and Edwards30 possibly because of concomitant medication with mood stabilisers and atypical antipsychotics inducing additional side-effects. Reference Ketter, Nasrallah and Fagiolini31 On the other hand, it is not possible to suggest an optimal allopurinol dosage, since included RCTs used heterogeneous dosages and relevant meta-regression did not show a dose–response relationship.

Finally, although a biological rationale for allopurinol use in clinical practice can be found in increased uric acid levels in people with bipolar disorder during manic and mixed episodes, further research is required to clarify the role of purinergic dysfunction in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder. Reference Ortiz, Ulrich, Zarate and Machado-Vieira3,Reference Muti, Del Grande, Musetti, Marazziti, Turri and Cirronis8,Reference Bartoli, Crocamo, Gennaro, Castagna, Trotta and Clerici32

Acknowledgements

We thank all the authors of the trials included in this meta-analysis. Special thanks are due to Serge Brand, David Luckenbaugh and Rodrigo Machado-Vieira, who provided important clarifications and unpublished data on their studies.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.