No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

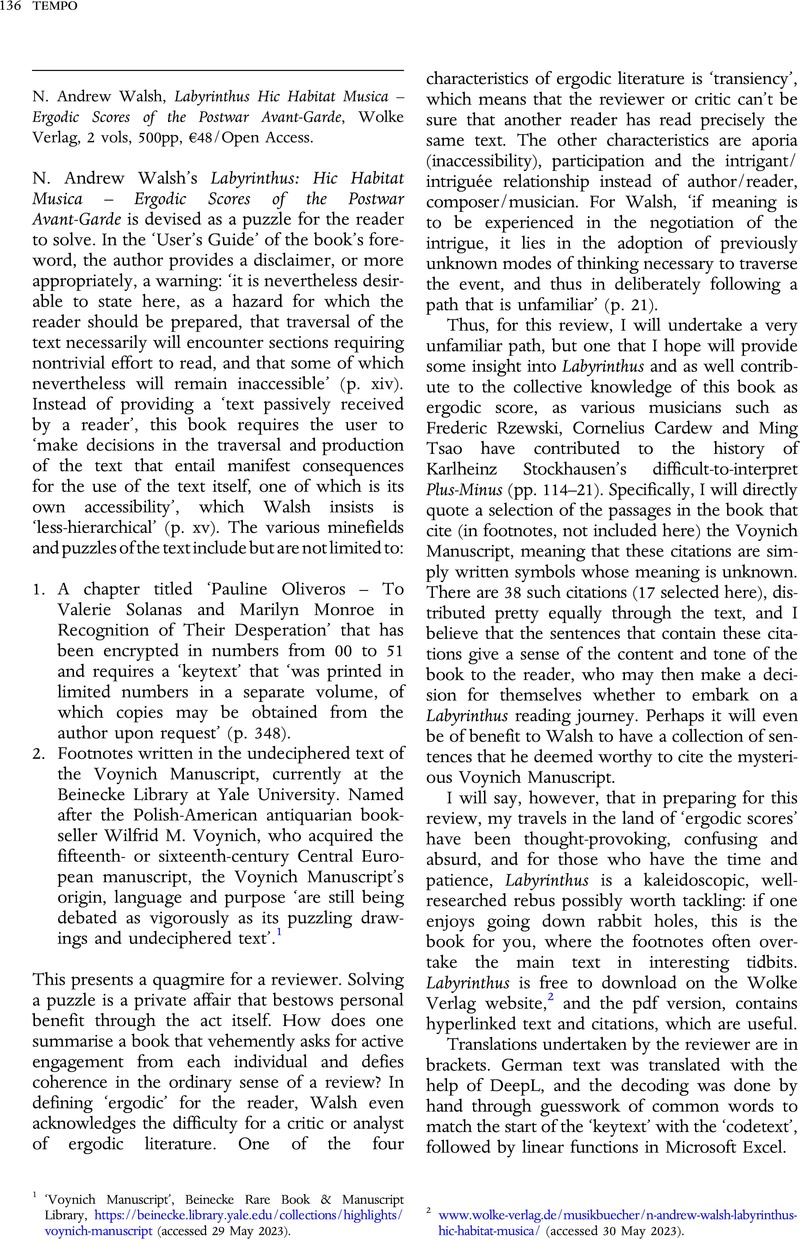

N. Andrew Walsh, Labyrinthus Hic Habitat Musica – Ergodic Scores of the Postwar Avant-Garde, Wolke Verlag, 2 vols, 500pp, €48/Open Access.

Review products

N. Andrew Walsh, Labyrinthus Hic Habitat Musica – Ergodic Scores of the Postwar Avant-Garde, Wolke Verlag, 2 vols, 500pp, €48/Open Access.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 September 2023

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- BOOKS

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press

References

1 ‘Voynich Manuscript’, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, https://beinecke.library.yale.edu/collections/highlights/voynich-manuscript (accessed 29 May 2023).

2 www.wolke-verlag.de/musikbuecher/n-andrew-walsh-labyrinthus-hic-habitat-musica/ (accessed 30 May 2023).