Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 February 2010

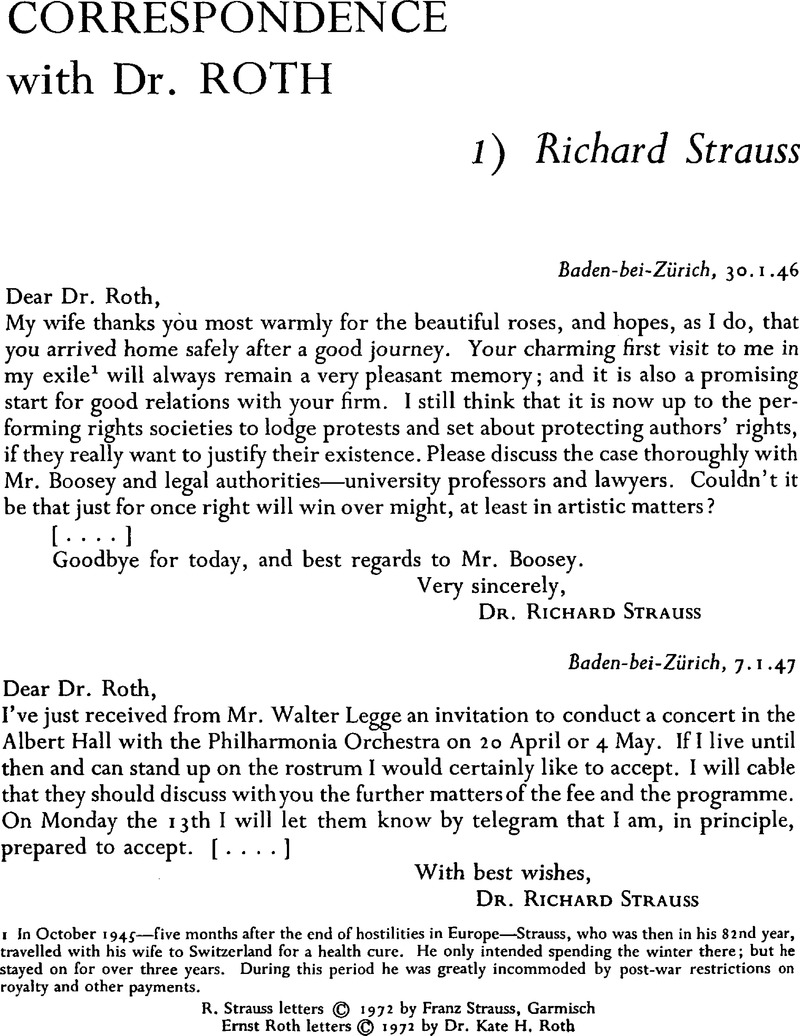

page 9 note 1 In October 1945—five months after the end of hostilities in Europe—Strauss, who was then in his 82nd year, travelled with his wife to Switzerland for a health cure. He only intended spending the winter there; but he stayed on for over three years. During this period he was greatly incommoded by post-war restrictions on royalty and other payments.

page 10 note 1 Permission was duly obtained from the British authorities.

page 10 note 2 Lawyer

page 10 note 3 Hotel owner

page 10 note 4 Noted patron of music, and gifted amateur clarinettist (for whom Stravinsky composed his Three pieces for clarinet solo).

page 10 note 5 Elder grandson of the composer

page 11 note 1 The work was eventually given the title ‘Duet-Concertino’.

page 12 note 1 The dates of Strauss's first post-war appearances in London had by now been postponed to October 1947.

page 13 note 1 i.e. Symphonische Fantasie ‘Die Frau ohne Schatten’ (1946).Google Scholar

page 13 note * cf. Der Rosenkatalier, Act II, end of Annina's ‘letter song’.

page 15 note 1 Leon Goossens, who had already played the concerto in Oxford.

1 The composers' elder son, who has been responsible for several cover designs for his father's scores, including Canticum Sacrum.

2 The article (entitled ‘In Memoriam Dylan Thomas: Stravinsky's Schoenbergian technique’) was published in TEMPO 35 (Spring 1955).

page 19 note 1 On 7 December 1961, the Symphony by Kodály received its first British performance simultaneously in London (by the London Philharmonic Orchestra under Ferenc Fricsay) and in Birmingham (by the City of Birmingham Orchestra under Hugo Rignold).

page 19 note 2 The actual text (from The Times of 8 12 1961 Google Scholar) reads as follows: ‘It is a symphony which unsophisticated people will enjoy to the full, and which must summon the admiration of those who look farther than for good tunes and rousing climaxes.’

page 19 note 3 The reference is to Kodály's first wife, Emma, and to the forthcoming publication (by Boosey & Hawkes) of her Valses Viennoises, for which Kodály provided the following introduction: ‘These melodies may reflect a few personal traits of a most remarkable woman, the beloved companion of my life for 48 years. She did not care to be published, or to figure as a composer; her music was just an organic part of her life, as well as her very fine piano playing and singing. She was a “phantom of delight” for everybody who met her.’

page 20 note 1 Musik als Kunst und Ware (Zurich, 1966).Google Scholar

page 20 note 2 Ansermet, Ernest, Les Fondements de la Musique dans la Conscience Humaine (Neuchatel, 1961).Google Scholar

page 20 note 3 Alois Melichar, German conductor, and author of two polemical books about modern music, with particular reference to ‘atonal’ and 12-note composition.

page 20 note 4 As a result of various disagreements with his publishers, Schoenberg decided in 1929 to try publishing his works privately. In 1929–30 his opera Von Heute auf Morgen was so published.