Introduction

A growing number of second and foreign language (L2 and FL) learners use digital game-based learning (DGBL) to develop language proficiency (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Dixon and Jordan2022). Although digital games can be characterized into various genres (e.g., special purpose educational games versus commercial off-the-shelf games; All et al., Reference All, Castellar and Van Looy2016), they share several common features that are valued for their pedagogical potential, including an emphasis on (a) player-driven choices, (b) task-based approaches, and (c) intrinsic motivation (Butler, Reference Butler2022). Game-based approaches can offer opportunities for learners to practice a target language in an interactive, immersive, and low-anxiety environment (Cerezo et al., Reference Cerezo, Moreno, Leow, Cerezo, Baralt and Leow2015; Reference Cerezo, Caras and Leow2016; Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Kao and Reynolds2012; Reinhardt, Reference Reinhardt2019). DGBL research with young FL learners, in particular, shows positive results in improving children’s language performance (Hazar, Reference Hazar2020; Hwang & Wang, Reference Hwang and Wang2016; Mazaji & Tabatabaei, Reference Mazaji and Tabatabaei2016; see also Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Rollinson, Plonsky, Gustafson and Pajak2021 and Loewen et al. Reference Loewen, Isbell and Sporn2020).

Literature review

Digital game-based learning to support language learning

DGBL research, however, is still in its early stages. A meta-analysis by Acquah and Katz (Reference Acquah and Katz2020) found that DGBL research has primarily focused on the implementation of digital games in or in tandem with formal classroom instruction. Butler (Reference Butler2022) points out the need for more studies that investigate how digital learning games work when used outside formal classroom settings. This is an important direction for DGBL research from the perspective of understanding how digital games impact not only language development but also the promotion of learner autonomy. An increasing number of games leverage technology to foster more self-direction for learners in their own learning experiences. Self-direction is generally understood as an autonomous process in which learners are the ones who initiate their own learning experiences, seeking out resources to facilitate their learning and enable them to meet their learning goals. This means that learners who are highly self-directed exhibit high levels of both autonomy and perseverance (Knowles, Reference Knowles1975). In a recent large-scale questionnaire-based study of online L2 learning involving 615 learners residing in 29 countries, Paradowski and Jelińska (Reference Paradowski and Jelińska2023) found that self-direction was an essential component, along with motivation, of successful outcomes for online L2 learning. With self-directed learning playing an increasingly central role in the gameplay of digital games for L2 learning, commercial language learning platforms are integrating components that enable their users to explore virtual environments (e.g., ImmerseMe, https://immerseme.co/, Pearson Education’s Mondly, https://www.mondly.com/vr), select their own material (e.g., Babbel’s flexible lesson models), and stay motivated with in-app prizes and friendly competition (e.g., Duolingo’s learning “streaks” and Friends Quests).

Research on the impact of DGBL outside formal classroom settings, specifically with young FL learners, has explored the relationship between gaming and a range of variables, including vocabulary. For example, Jensen (Reference Jensen2017) found that English-related extramural gaming among 8- and 10-year-old Danish learners of English was significantly related to higher vocabulary scores. In a study of 10- and 11-year-old Swedish learners of English, Sundqvist and Sylvén (Reference Sundqvist and Sylvén2014) explored young learners’ gameplay as well as the relationship between gameplay and factors such as gender, motivation, self-assessed English ability, and self-reported strategies related to speaking English, revealing some positive trends for learners who were frequent gamers. Building on this research, Sundqvist (Reference Sundqvist2019) undertook a large-scale, longitudinal study following 1,340 Swedish adolescent language learners of English in their ninth year of formal schooling (ages 15–16). The study explored the relationship between the types of games adolescent language learners play, the amount of time they played the games, and their L2 English vocabulary development. To investigate the relationship between informal language learning, formal language instruction, and overall vocabulary development, Sundqvist identified four distinct categories within her adolescent learners: (a) nongamer or those who did not report playing any games, (b) single-player (SP) games in which learners only interacted with the game interface, (c) multiplayer (MP) games where multiple players played locally on the same device, and (d) massively multiplayer online (MMO) games where players from around the world can play with one another simultaneously. Data on the learners’ gameplay habits were collected via questionnaires and interviews. The adolescent learners’ language proficiency was measured through two vocabulary tests (receptive and productive), an essay, national test scores, and year-end report cards. The results showed that the two strongest predictors of L2 English vocabulary development were time spent playing games and social interactions while playing games (i.e., those who played MP games or MMO games performed better than those who did not play games or played alone). Lastly, those who played SP games performed better than the nongamers who did not have extracurricular exposure to L2 English language via any type of gameplay.

Additionally, DGBL has been studied as part of a larger, formal, classroom-based setting, such as digital review games commonly used by L2 teachers to review discrete skills or lexical items. For example, in their longitudinal study of collaboration, engagement, and competition investigating language use during in-class L2 vocabulary repetition games (via Kahoot!, a digital quiz platform), Sandlund and colleagues (Reference Sandlund, Sundqvist, Källkvist and Gyllstad2021) demonstrated that learners used embodied actions like response cries, complaints, and assessments to co-construct and display their orientation to L2 vocabulary learning. Over the course of four academic years, the research team collected classroom observation video data from six multilingual English classrooms in Sweden (each group was in year 9 when they participated).

These studies provide evidence in support of what has been called extramural language learning (by Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist2009), being used to positively supplement formal language education and to encourage games in which interaction with other players is incorporated. This paper will use the term extramural language learning as opposed to informal language learning or naturalistic language learning because, as Sundqvist and Sylvén (Reference Sundqvist and Sylvén2016) put it, this kind of language learning

is not initiated by teachers or other people working in educational institutions; the initiative for contact /involvement lies with the learner himself / herself or, at times, with someone else, such as a friend or a parent. Thus, in general, contact / involvement is voluntary on the part of the learner, though there is also the possibility that learners engage in specific [extramural language learning] activities because they feel pressured to do so, for whatever reason (p. 6).

However, interpreting and synthesizing results of different studies on DGBL is somewhat complicated by the operationalization of terms like “playing games,” as well as high levels of variation in learners’ individual gameplay experiences and logistical difficulties in collecting detailed, reliable data at the individual level in relation to learners’ in-game engagement (see All et al., Reference All, Castellar and Van Looy2016 for a discussion). Furthermore, while adolescent learners are considered young learners in the field of second language acquisition (SLA), it is difficult to generalize results from studies such as Sundqvist’s to the much younger population represented in the current study. Fewer studies have focused on very young learners’ experiences with digital learning games specifically designed to be played outside classroom settings, particularly those games and apps capable of recording individual-level data about learners’ in-game engagement and choices.

The current study aims to fill this gap by shedding light on one such implementation of a mobile app-based digital game—ABCmouse English—designed for young EFL learners to use anywhere at any time. The app was designed based on a research-driven, game-based approach to L2 learning, combining incrementally developmentally sequenced lessons with unstructured, exploration-based environments, giving learners a high degree of control over what, how, and at what pace they learn.

English education of young children in Japan

Educational policy in Japan includes the use of English examination scores for college admissions or job opportunities, making English learning for young children very important. English education in Japan has been compulsory in secondary grades since just after World War II (Shimizu, Reference Shimizu2010). In elementary schools, English language education began in 1992 when the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) selected two elementary schools and one junior high school in Osaka to implement experimental English activities in public education (Triana, Reference Triana2017). In 2002, MEXT announced a proposal to have students achieve communicative competence in English and provided new guidelines for teaching English. These included improving the teachers’ skills and having English taught through the medium of English (Shimizu, Reference Shimizu2010). In 2014, timed with the announcement of Tokyo as the seat of the 2020 Olympics, MEXT announced a plan to reform English education so that the instructional goals are aligned with globalization. This included nurturing the foundations for communication skills starting in the third and fourth grades (MEXT, 2014). The 2014 reform plan also included measures to improve the teaching skills of elementary school class teachers and promoted the use of assistant language teachers (ALTs)—foreign nationals with native-level English skills. However, the plan did not include any guidelines for English language education for students in grades 1 and 2, suggesting a lack of guidance for English education for younger children.

In this context, many Japanese parents seek extramural English lessons for their children or self-help bilingual parenting resources to try to increase their children’s exposure to English at home (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2023). Some of these resources recommend media as the source of English language input for children, recognizing that Japanese parents may not have adequate English language proficiency to provide the linguistic input that would help their children’s English vocabulary and grammatical development (Nakamura, Reference Nakamura2023). The app employed in the current study provides a self-guided game that young Japanese children can use to develop communicative skills in English from early on and, thus, is well suited for use in the Japanese context.

Developing a digital language learning app informed by principles of learning, motivation, and second language acquisition

Studies show that app and game design and learner engagement are critical factors that determine an app’s effectiveness in promoting positive learning outcomes (Berkling & Gilabert Guerrero, Reference Berkling, Gilabert Guerrero, Koivisto and Hamari2019; Chen, Reference Chen2018). In this study, the collaborative team of curriculum specialists, English teachers, second language researchers, and game developers who created ABCmouse English sought to build a game-based app that would keep learners engaged and motivated to continue learning while providing input and output opportunities that matched and drove developmental levels. The team considered theories of motivation, L2 learning, and L2 assessment to create an app that was developmentally appropriate, engaging, and designed for use in informal learning settings (see Arndt, Reference Arndt2023).

ABCmouse English promotes engagement and motivation through an activity-based game environment designed to foster independent, active learning. Learners are encouraged to spend 15 to 20 minutes a day using the app, which offers them relatively compact and highly engaging play sessions. Players (henceforth, “learners,” as we discuss them in relation to their experiences playing to learn English) exercise autonomy by freely choosing activities from three different play environments. One environment is a structured learning path that guides learners along a sequence of activities with incrementally more developmentally advanced language objectives. The interactive games in the app provide linguistic problems of increasing difficulty (e.g., new vocabulary words or sounds that may be challenging to pronounce), keeping the experience within, but at the outer edge of the learner’s competence (Gee, Reference Gee2005). A second environment is an open exploration area that offers opportunities for learners to repeat and review content that they have already encountered on the learning path without being exposed to new language forms and is designed to promote linguistic automatization. The third environment in the app is a free-play area where learners can use tickets that they have earned through gameplay, exploring puzzles, songs, videos, and games based on their interests. Learners can customize their learning by choosing their games and environments and trying out new activities. New language is introduced in contexts that the children have selected based on their interests, increasing the chance that they will be motivated and engaged.

Each activity throughout ABCmouse English is designed to last about three minutes, with a play session intended to consist of approximately 5 to 6 activities (i.e., a typical play session would last about 18 minutes). This design was to leverage the extramural learning setting to promote learner autonomy in two ways. First, learners have agency over their own learning experiences by choosing what to focus on every few minutes. Second, learners can decide how many sessions to engage in and when to do those sessions. Although the app does not limit how long a learner can engage with the game in one sitting, the recommended usage is 15 to 20 minutes at a time to avoid learner fatigue while maximizing engagement.

Importantly, ABCmouse English was designed based on key principles from L2 learning research. Studies show that learners learn best through technology when doing tasks or activities that use language to accomplish a goal rather than activities aimed solely at learning the grammatical aspects of the language (e.g., Heift et al., Reference Heift, Mackey and Smith2019). Activities in the app used in this study were designed to engage young learners in authentic contexts (i.e., situations that are relevant or familiar to children based on their lives outside of the language learning app) (Long, Reference Long2015; Reference Long2016), which has also been shown to increase engagement and interest (Pinter, Reference Pinter2019). The activities were designed to promote immersive learning experiences involving familiar topics such as family, pets, toys, food, numbers, and colors so that learners need to understand the language to complete an activity. In other words, the focus is on meaning, but linguistic form is important for comprehension (e.g., Doughty & Long, Reference Doughty and Long2003; Long, Reference Long2015; Long & Robinson, Reference Long, Robinson, Doughty and Williams1998). The app used “focus on form,” which, in the L2 research literature, is distinct from a focus on formS, as in grammar drills. Rather, a focus on form, is where the context is meaning, but form understanding is important. Focus on form has been shown to be effective in multiple primary studies (e.g., Gholami, Reference Gholami2022; Rassaei, Reference Rassaei2020) as well as metanalytic work in instructed L2 research (Lee & Lee, Reference Lee and Lee2022; Norris & Ortega, Reference Norris and Ortega2000; see also Doughty & Williams, Reference Doughty and Williams1998).

The activities in the game encourage learners to construct knowledge through trial and error as they produce the L2 while receiving developmentally appropriate types of implicit and explicit feedback when they need it (Mackey, Reference Mackey2012). Learners are also exposed to meaningful, comprehensible input through pedagogical tasks and content (e.g., song-based input, followed by pronunciation games). Learners’ developmental levels are considered throughout the games, which build on the learners’ developing knowledge (Gass, Reference Gass2017). In designing the app, L2 research principles were supplemented with considerations of measurement and assessment. The Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) standards (Council of Europe, 2020), the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL) guidelines (ACTFL, 2012)—along with developmental sequence work on what is learnable and teachable (e.g., Pienemann, Reference Pienemann1998)—were all considered as underpinnings for the app, including the sequence in which language is presented in the game’s learning path. Figure 1 below provides examples of activities in the app.

Figure 1. Sample Activities in ABCmouse English.

The app design was also informed by spaced repetition theory in SLA, which posits that the timing of review and practice affects learning, and that practice can be more effective when spaced out over time rather than when grouped together (Nakata & Suzuki, Reference Nakata and Suzuki2019; Rogers, Reference Rogers2017; Seibert Hanson & Brown, Reference Seibert Hanson and Brown2020; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Zou and Xie2022). Based on this research and other work on efficient memory-building techniques, the app repeats and reviews content in an algorithm-driven pattern to enhance long-term retention (Tabibian et al., Reference Tabibian, Upadhyay, De, Zarezade, Schölkopf and Gomez-Rodriguez2019). Also incorporated into the design of the app is a consideration of the importance of learning from scaffolded target language input (Bang et al., Reference Bang, Olander and Lenihan2020; Mahan, Reference Mahan2022; Moeller & Roberts, Reference Moeller, Roberts and Dhonau2013), formulaic sequences (Ellis, Reference Ellis2012; Wray, Reference Wray2000; Reference Wray, Siyanova-Chanturia and Pellicer-Sánchez2018), and a focus on communication. All of these are woven into the presentation of the learning path’s lessons, practice, and production skills, with interactive activities designed to foster the development of fluency (Shrum & Glisan, Reference Shrum and Glisan2009).

The current study focuses on understanding the outcomes and experiences of young Japanese L1 children who used a research-driven self-guided language learning app to learn English as a foreign language in nonclassroom settings. Specifically, the research has two main goals: to (a) determine the extent to which a self-guided English learning app used outside school, can effectively help young learners develop English skills and (b) understand the relationship between in-game choices and the development of English skills.

Research questions

The research questions guiding this study are:

-

1. To what extent is a self-guided English language learning app effective in promoting Japanese seven- and eight-year-old children’s English language development?

-

2. To what degree did children stay engaged with the app throughout the duration of the 16-week study?

-

3. What relationships, if any, exist between children’s in-game choices and their English learning outcomes?

Methods

Research design

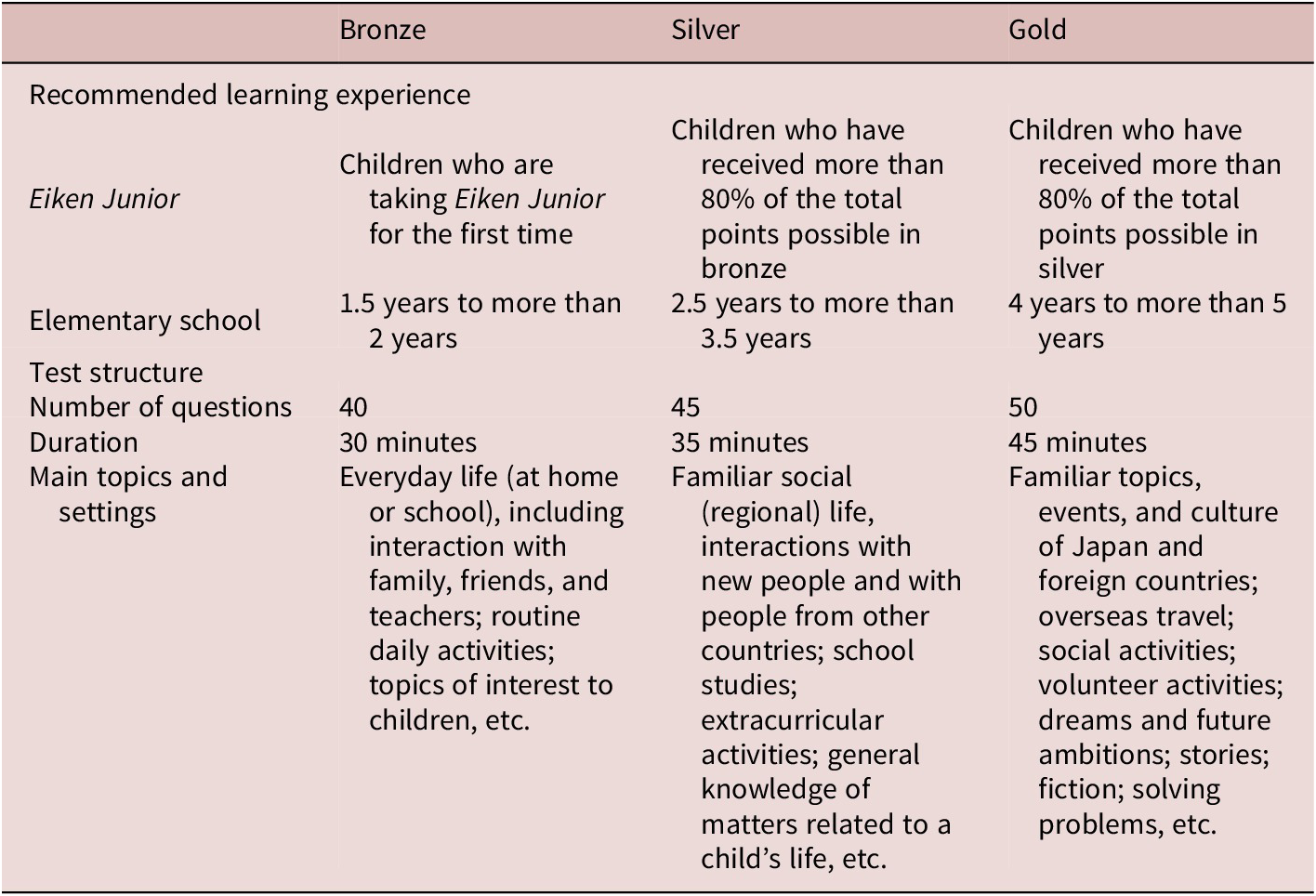

A randomized controlled trial design was used for this study to understand the extent to which the app promoted Japanese children’s English language development. We operationalized development, as we specify in greater detail shortly, as learners’ transferable language skills developed as a result of app use, in addition to improved performance on a broader set of vocabulary or grammatical forms. A sample of children across Japan was recruited, with half randomly assigned to use the app at home for a period of 16 weeks (n = 74) and the other half assigned to a control group that did not use the app for the study duration (n = 74). In-app data were used to examine children’s engagement levels and their play behaviors, that is, in-game choices. Pre- and post-assessments were administered to measure children’s English language abilities at the start and end of the study, and a combination of Qualtrics surveys, Zoom-based focus groups, and interviews was conducted to collect information regarding children’s and their families’ experiences using the app (see Figure 2 below). The study was approved by a U.S.-based institutional review board, and the researchers obtained informed consent from the parents of all participants in the studyFootnote 1. A Japan-based research team dealt with recruitment, communication with participants, and logistics associated with scheduling and administering the English language assessments.Footnote 2

Figure 2. Study design.

Experimental and control conditions

After the pre-assessment, the 148 children were randomly assigned to either the control group (n = 74) or the experimental group (n = 74) after balancing for pretest scores, age, sex, and engagement in external English activities. Children in the experimental group were provided free one-year accounts to the app and recommended to use it for a minimum of 15 to 20 minutes daily, six days a week. Researchers kept track of the participants’ usage on a weekly basis by examining the analytic data collected by the app. Efforts to encourage consistent usage throughout the study included weekly emails to parents to let them know what their child’s usage levels were, periodic motivational videos sent to all children, and occasional phone calls to parents of children with unusually low usage to inquire about possible technical issues. Importantly, however, parents were specifically asked to encourage but not coerce their children to use the app. For example, telling their children that they must use the app for a certain amount of time prior to engaging in another activity (e.g., “You must use your English app for 10 minutes before you can switch to your video game”) would have been considered coercion. Parents were asked to avoid such strategies when encouraging their children to use the app.

Children in the control group did not use the app for the duration of the study. They were asked to continue any English language learning activities that they had already been engaged in prior to the start of the study, but not to start anything new during the study. Parents in both groups were asked to refrain from having their children start any new English learning programs throughout the study period but were instructed to continue with whatever learning they were already doing. A little more than half the children in each group (experimental = 60%, control = 57%) were already learning English—for example, at school, at juku (formal learning contexts outside of school, often in the evening or weekends), via “conversation classes” with native speakers, through English-oriented television programs, and other commercially available English learning materials. Involvement in the current study did not involve any manipulation—for example, stopping, starting, changing—of a formal instruction component.

Participants

Recruitment for the study took place over a three-month period. Children were eligible to participate if they (a) were between seven and eight years of age as of the last day of the recruitment period, (b) did not spend more than an hour a week outside school learning English, and (c) had access to a computer or tablet device at home so that they could use the app and participate in the language assessments, focus groups, and interviews that were administered over Zoom. An initial sample of 152 children and their families was recruited, 148 of whom ultimately participated in the study. Two children of the 152 withdrew before the start of the study, and two others scored highly on the pretest, indicating that their current level of English exceeded the highest level of the app and, therefore, they were ineligible to participate in the study.

In the sample of 148 children and their families, 25 out of 47 prefectures across Japan are represented, with 68% (50 in treatment, 51 in control) residing in one of the major metropolitan areas of Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, Osaka, and Chiba. Seventy-three percent of parents participating in the study (53% in treatment, 54% in control) had a bachelor’s degree or other professional degree.

English language assessments

Two measures of English language proficiency were used to assess children’s learning gains on specific language skills that are both appropriate to the children’s age and current language level and are within the learning outcomes covered by the app. One was an app-aligned listening and speaking assessment created by the team that developed the app to specifically target children’s knowledge of the language taught in the app (referred to as the “app-test” hereafter). The second assessment was Eiken Junior, a well-known suite of tests that aims to determine the English listening and reading ability of Japanese children and encourage their English learning and development (Eiken Junior, Reference Eikenn.d. https://www.eiken.or.jp/eiken/en/jr_step/). The language on Eiken Junior covers a range of basic, familiar content, some of which are included in the app and some of which are not. Both tests were administered to children participating in the study at two different sessions to measure their learning gains over time: once at the start of the study and a second time four months later at the conclusion of the study. The use of the term “learning gains” here and elsewhere in this paper refers specifically to children’s development in the language skills measured by the two assessments and should not be equated with a comprehensive measure of their language proficiency. For example, English writing is not covered, as the app is primarily focused on developing children’s listening, reading, and speaking abilities, and Japanese children of this age are not expected to be highly proficient in writing in English.

The app-test, specially designed for the current study, was administered by a group of 14 trained assessors who conducted and scored children’s performance in one-on-one live Zoom sessions with the children. All the assessors were bilingual Japanese–English undergraduate or graduate students studying to become English language teachers. Assessors were blind to which children belonged to the group using the app and which belonged to the control group. Parents were requested to be available throughout the testing sessions to put their children at ease and troubleshoot any potential technical issues that arose, either by sitting next to their child during the assessment or by staying within calling distance. Parents were carefully instructed not to give input, coaching, or hints that could affect the child’s responses to test questions. The tests took place after school hours on weekdays and throughout the day on weekends.

The app-test targeted knowledge of linguistic forms that children were exposed to through their 16 weeks of using the app (see Appendix A). The test includes 25 items across five sections: vocabulary identification, listening for meaning, pronunciation, speech production, and conversation (see Table 1). Sample items from each section are shown in Appendix B. Each section begins with a sample item to explain the instructions to children, and each section includes a random “motivator” item designed to be very easy and answerable by the majority of children to build their confidence (e.g., being shown a picture of pizza, a word that most Japanese children would be expected know, and being asked, “What is this?”) For each item, the assessor orally read the question to the child or showed them the item prompt, and the child then had up to 20 seconds to provide the correct answer. The assessors provided encouragement after every response, such as “thank you,” whether correct or incorrect, with no feedback given to indicate to the child whether they provided the correct answer. Two separate versions of the test were created and randomly assigned so that children would not see the same items on the pre- and posttests. Immediately upon completion of the app-test, children and their parents were provided with an online link to the Eiken Junior website and requested to take it as soon as possible.

Table 1. App-test subsectionsFootnote 3

The experience of taking either test involves the provision of additional language input to the children, which is important to note, as this additional input might have some effect on learners’ performance. The app-test was presented first in both the pretest and posttest administrations consistently across all children, as opposed to randomizing. We standardized the order of tests in this way to facilitate parents’ administration of the Eiken Junior immediately or soon after the app-test because our pilot data indicated that the Eiken Junior was more variable in administration time, which could potentially have led to participants feeling rushed or being late for scheduled Zoom sessions for the app-test. Table 1 illustrates the subsections of the app-test.

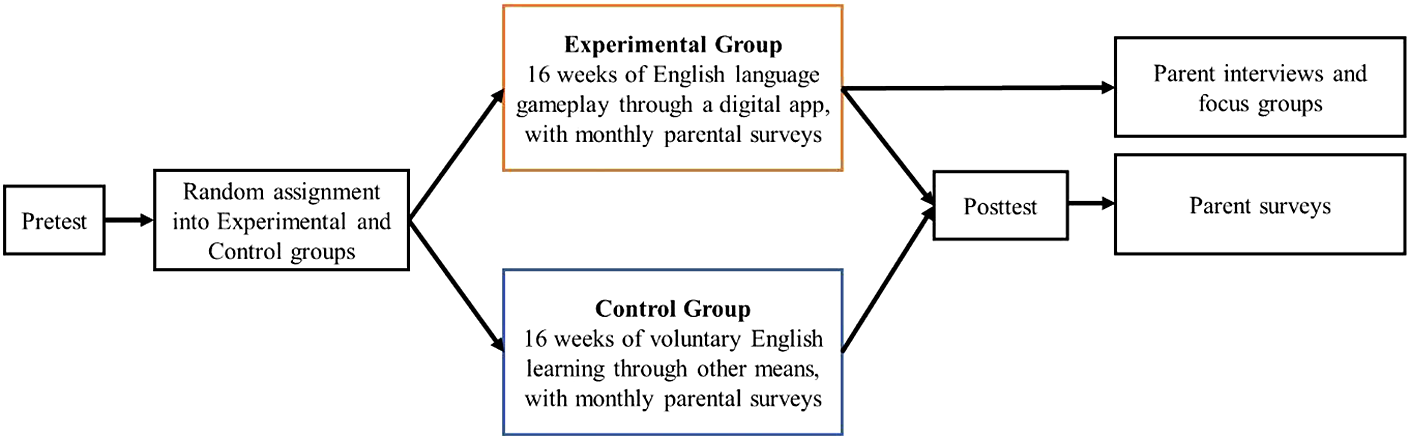

The Eiken Junior is a popular suite of tests designed to foster English communication skills for Japanese children learning English and consists of three leveled tests representing increasing levels of difficulty: bronze, silver, and gold. Each level consists of three sections: listening for vocabulary, dialogues, and sentences, with the silver and gold levels including an additional reading section. The vocabulary, expressions, topics, and settings assessed by the items are based on situations with which children are familiar. Table 2 illustrates the structure of Eiken Junior along with the amount of English language instruction at school that is recommended prior to a child taking each level. The current study used the online version of Eiken Junior, which is automated and available for children to take year-round. As with the app-test, two parallel versions of Eiken Junior were used so that children did not see the same items in the pre- and post-assessment administrations.

Table 2. Recommended learning experience and test structure by level for Eiken Junior (adapted from https://www.eiken.or.jp/eiken/en/jr_step/)

At the start of the study, all children took the bronze level of Eiken Junior. Following the recommended protocol, children who scored 80% or higher on a particular level were asked to take the next level of the Eiken Junior within a short period of time (usually within a few days) until they either received a score less than 80% or, in the case of two children, scored 80% or higher on the gold level (and were excluded from the study). The goal was to find a level where children still had room to improve after using the app (or not, as with the control group), and improvement could be measured when the test was administered again 16 weeks later. A similar process was followed at the end of the study, with children starting by taking the highest level of the assessment that they had reached at the start of the study. For example, a child who ended up taking the silver level at the start of the study started by retaking the silver level at the end of the study and then moving on to gold if they had progressed that far.

Survey measures

Online surveys were used to collect data about the experimental group children’s and families’ experiences with ABCmouse English. Parents of children in the experimental group completed a final online survey in Japanese (administered via Qualtrics) designed to gather information about their children’s experiences with the app and to obtain parental feedback in relation to specific games and features within the app. Questions posed included querying the extent to which parents believed their children’s English language outcomes had improved (or not), as well as focusing on the impact that the app had on children as learners. It must be acknowledged that not all parents had the same L2 English proficiency, and thus may have unintentionally over- or underestimated their children’s English development simply because they did not have enough L2 themselves to detect changes in their children’s English.

Focus groups and interviews

In addition, a subset of experimental group parents whose children had averaged at least 60 minutes of usage per week throughout the 16-week study period was invited to participate in either focus groups (n = 14 in groups of 3–4 parents at a time) or one-on-one interviews (n = 8). The focus groups and interviews were conducted in the parents’ first language, Japanese, with the objective of eliciting further information about how children and their families used the game, how they incorporated it into their daily lives, their level of engagement, and their attitudes and beliefs about learning English. The focus groups were approximately 45 minutes in length, and the one-on-one interviews were approximately 20 minutes in length. They were semistructured and largely followed a predetermined protocol, which included questions, such as “To what extent was your child engaged/engrossed/ “in the moment” when using the app?” and “How would you describe your child’s interest in English before/since using the app?” The audio recordings of the focus groups and interviews were transcribed and then translated into English. Data analysis followed an inductive grounded approach where emergent trends were identified in the transcripts and then used to add insight to the quantitative results.

Results

RQ1: To what extent is a self-guided English language learning app effective at promoting Japanese seven- and eight-year-old children’s English language development?

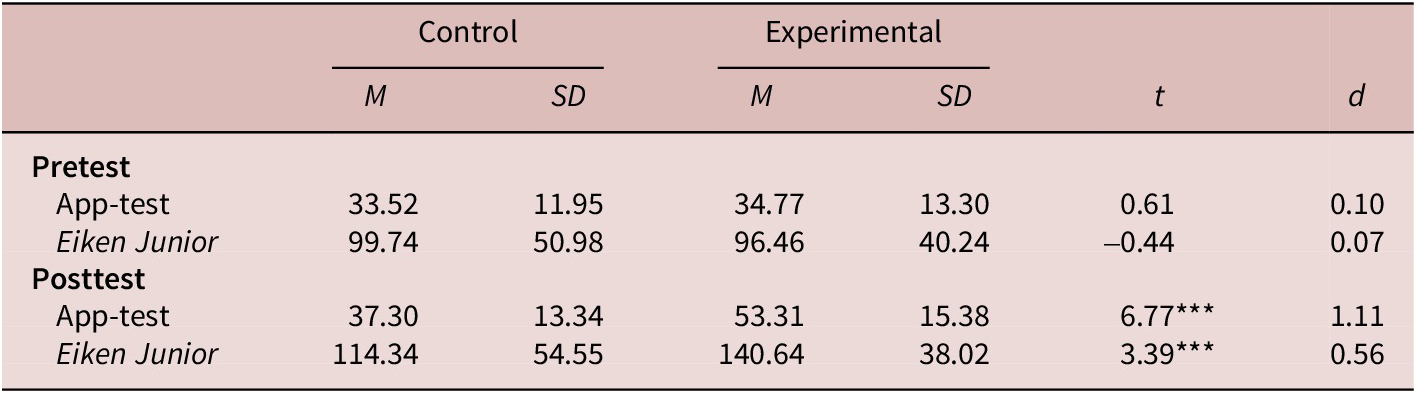

To address this first research question, children’s English abilities measured by both the app-test and Eiken Junior were examined. Changes in the scores of the experimental group, who used the app for 16 weeks, were compared to changes in the scores of children in the control group. Prior to the start of the experiment, there was no statistically significant difference in pretest scores between children assigned to the experimental group and the control group on both the app-test (t(148) = 0.61, p = 0.55) nor Eiken Junior (t(147) = 0.44, p = 0.66)Footnote 4 (Table 3).

Table 3. Pretest and posttest score comparisons between control and experimental groups

*** p <.001

As explained earlier, the purpose of the app-test was to measure children’s listening and speaking abilities related specifically to language and content that they were exposed to in the first two levels of the app, that is, language that the majority of children in the study would have experienced through playing the app. The reliability of the 25-item app-test was α = 0.72 for the pretest form and α = 0.82 for the posttest form.

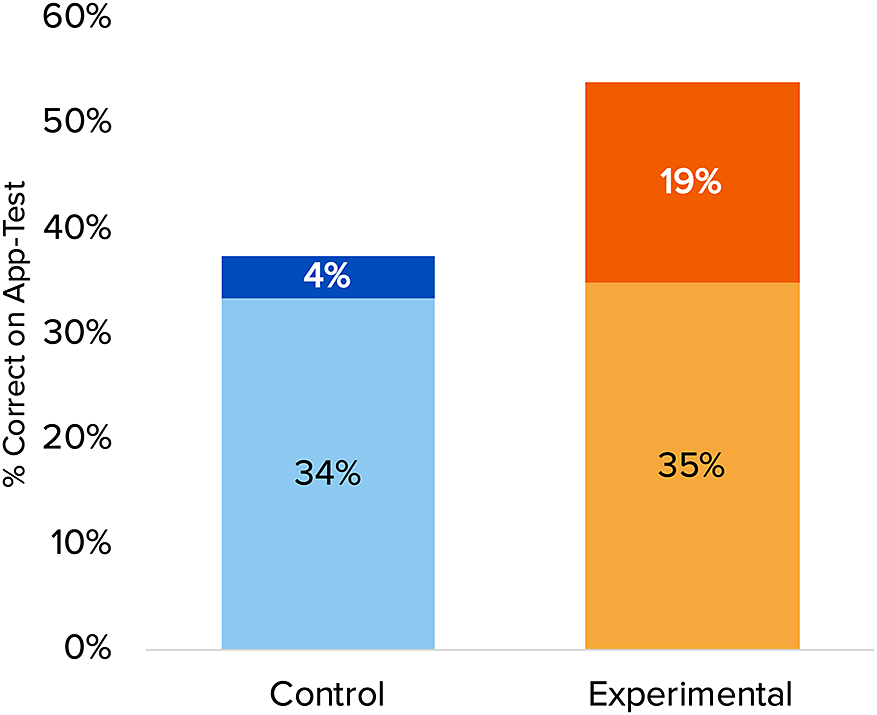

On the app-test, children who used the app improved by 19 points (95% CI = [13.87, 23.21]) compared to an improvement of 4 points (95% CI = [–0.34, 7.90]) by the control group children (Figure 3). A t-test on posttest scores indicated that the experimental group children improved significantly more than their peers in the control group (t (148) = 6.77, d = 1.11, p <.001). As the app-test was designed by EFL specialists on the same team that developed the app, the researchers were satisfied that it was an appropriate measure of how well children learned the language content they were exposed to in the app.

Figure 3. Average pre- and posttest score gains on app-test.

Analyses of the pre- and posttest scores of the subsections of the app-test showed that gains across all subsections for the experimental group children were positive and larger than gains made by the control group children (Table 4). Comparisons between posttest score gains between the groups on the subsections were all statistically significant at p <. 01, with effect sizes ranging from 0.52 to 0.86 (medium to large). The Cohen’s d effect size (d) included alongside the t-statistic and significance level (Table 4) offers additional context for interpreting the program’s impact in practical terms. Here, the effect size scales the difference in average posttest scores between the treatment and control group children relative to what can be considered typical variation in the scores across students in general (measured as the pooled standard deviation across all the scores). For example, an effect size of 1.11 indicates that the difference in average posttest scores between the two groups was 111% times as large as the typical standard deviation in test scores. In other words, using the program had an average impact of increasing children’s scores by more than one standard deviation, a substantial and meaningful impact.

Table 4. Average pre and posttest score gains by subsection of the app-test

*** p <.001, ** p <.01

An investigation of Eiken Junior CSE scores showed that the scores of children who used ABCmouse English improved on average by 44 points (95% CI = [31.45, 56.89]) compared to an improvement of 15 points (95% CI = [–2.59, 31.82]) in the control group (Figure 4). A t-test using posttest scores also indicated that experimental group children improved significantly more than their peers in the control group (t (147) = 3.39, d = 0.56, p < 0.001). While reliability statistics for the Eiken Junior were not available at the time of writing this paper, the Eiken Junior website emphasizes that while one purpose of the test is to determine a child’s English test scores, other important goals of the test include motivating them to learn English, helping them feel a sense of accomplishment as they learn, and understanding that English is a tool for communicating with people around the world. Therefore, in addition to reporting children’s growth on the CSE scale, we also report the percent of children in our study who achieved each of the levels of the Eiken Junior on the posttest, shown in Figure 5. The levels that children reached may be more reliable indicators of their language ability than CSE scores. While children in the experimental and control groups were similar in the levels of Eiken Junior that they achieved on the pretest, children who used the app were more likely to achieve higher levels by the time of the posttest when compared to the control group children.

Figure 4. Average pre- and posttest score gains on Eiken Junior.

Figure 5. Posttest level reached on Eiken Junior between control and experimental groups.

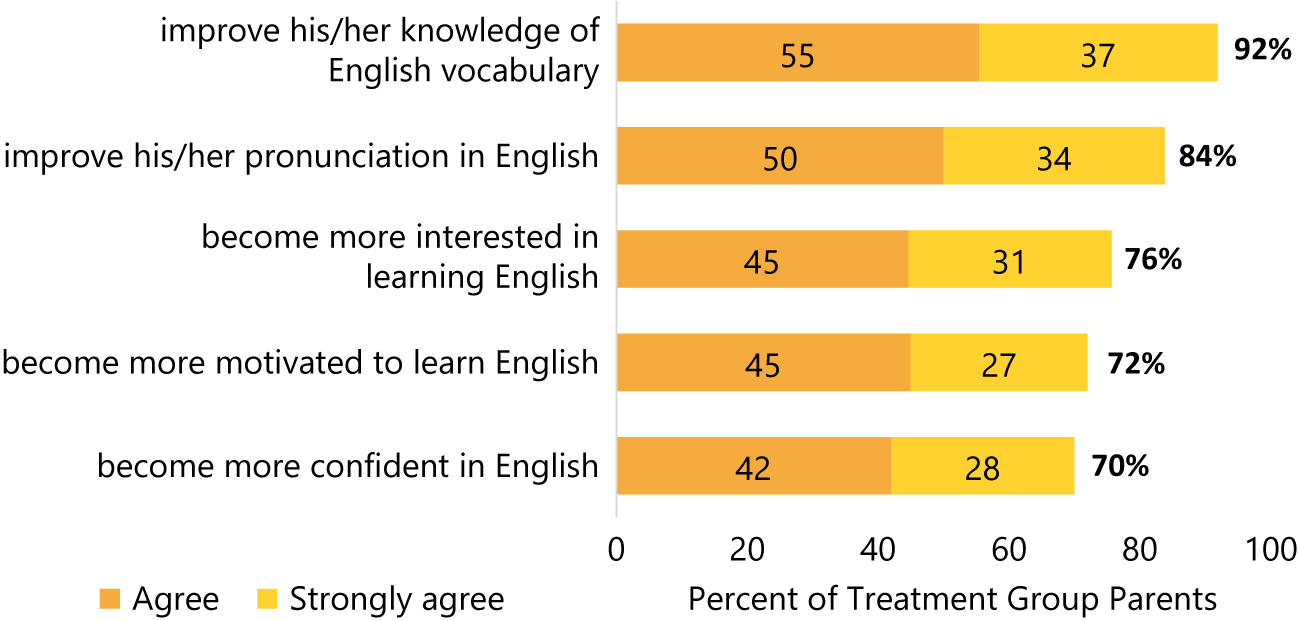

Data collected through the parent surveys described earlier provided additional context for the impact of using the app. In relation to a question about the extent to which they believed the app helped their children improve in English, 92% of the respondents (68 of 74 parents) indicated they strongly agree or agree with the statement that the app helped their children improve their knowledge of English vocabulary. Additionally, 84% of the respondents (62 of 74) reported they strongly agree or agree that the app helped their children improve their pronunciation in English. In other words, parents’ beliefs reflected the patterns shown in the tests, that is, the app had a positive impact on children’s English learning outcomes. Figure 6 below shows the survey responses of experimental group parents who indicated how using the app helped their children in learning English.

Figure 6. Parent responses to questions about the extent to which the app helped their children’s English learning (n = 74).

RQ2: To what degree did children engage with the app throughout the duration of the 16-week study?

The second research question focuses on how engaged children were with ABCmouse English over the duration of the 16-week study period. Engagement was operationalized for the purposes of this study as the time (number of minutes) students spent playing the app and with the activities. In-app tracking data revealed that the children maintained a high level of engagement using the app over the 16 weeks. On average, they used the app for 101 minutes each week (SD = 48), completing 61 unique activities each week (SD = 27) (Table 5). Engagement was also consistent throughout the study, with weekly usage across all children averaging above 80 minutes for all 16 weeks (Figure 7).

Table 5. Engagement statistics for treatment group

Figure 7. Average weekly usage (minutes) and activity completes (N) during the study.

At the time of the study, the learning path consisted of four levels, with Levels 1 and 2 designed to take a child approximately 24 weeks to complete at a typical level of play (approximately 15–20 minutes per day, six days per week). Over the span of the 16-week study period, experimental group children exceeded this expectation, with 52 children completing Level 1 and 36 completing Level 2.

In interviews and focus groups, parents were asked to discuss their observations in relation to their children’s engagement with the app and its positive impact on their children as learners. Here are some typical comments:

The results were so much better than I had expected. At first, she had no interest in English. She was anxious because she was not very good at English, but then she started the app, and she went from having a strong sense that she was poor at it to appearing to not feel that way at all. She says words on a regular basis and says things like, “I know this. I’ve heard this before,” while watching TV, and I could see her growth in her daily life. She also says she likes her schoolwork now. She used to say she didn’t like it, so I’m happy for her (parent of a second-grade child).

Another parent invoked similar themes:

His vocabulary has grown, and his speaking has improved dramatically, as well as his intonation. Also, his personal reluctance to learn English has vanished. The exam he completed the other day was far better than the results of the first, and he was clearly able to converse with the teacher. The English teacher at his primary school—he came home excited because the teacher complimented him on his pronunciation. It gave him confidence (parent of a second-grade child).

RQ3: What relationships, if any, exist between children’s individual in-game choices and their English learning outcomes?

The third research question pertains to the choices children made as they customized their individual learning experiences in the app and whether there was any relationship between the choices they made and their learning gains. Their choices were based on when and how long they played ABCmouse English each day, as well as the in-app environment in which they chose to play.

Over the 16 weeks, the children varied considerably in how they spent their time playing in different game areas. We operationalized the choices that children could make in their gameplay using the following five metrics:

-

• Their total time playing per week in minutes

-

• The number of unique days they played per week

-

• The number of unique activities they completed per week

-

• The percentage of their total play time spent in the exploration area

-

• The percentage of their total play time spent in the free play area

In particular, children varied in their playtimes in the exploration area and free area, which ranged from 0 to 34% and 0 to 61%, respectively, as a percentage of children’s total active playtime.

We then examined whether any of these metrics were associated with children’s learning gains using correlational analyses. The following variables were associated with learning gains on either the app-test or the Eiken Junior, or both: (a) the total time played per week, (b) the unique number of days they played each week, (c) the number of unique activities completed per week, and (d) percentage of total play in the exploration area. These findings are summarized in Table 6 below.

Table 6. Descriptive statistics on children’s play behaviors across 16 weeks and correlations with gain scores (N = 74)

* p <. 05, *** p <. 001

Regression analysis was used to investigate the relationships between these metrics in combination with each other and with gain scores on the app-test and the Eiken Junior. Two models were specified, one whose dependent variable was children’s gain scores on the app-test (Model 1) and the other whose dependent variable was children’s gains scores on Eiken Junior (Model 2). In each model, children’s pretest scores on the relevant test, along with the four variables that had statistically significant correlations to gain scores, were included as potential covariates. Stepwise forward selection was used, whereby a model begins with no covariates and iteratively selects the variable with the most predictive power, keeping only those that are statistically significant until the optimal model is reached. The results of the regression analysis are shown in Table 7.

Table 7. Regression models predicting score gains on the app-test (Model 1) and Eiken Junior (Model 2)

* * p <.01, *** p <.001

Controlling for children’s level of English knowledge at the start of the study (their pretest scores), significant positive predictors of learning gains on both the app-test and the Eiken Junior test included the number of activities they completed per week and the percentage of time they spent in the exploration area. Neither children’s total time on the app per week nor their number of unique play days per week were significant predictors of their learning gains when the other metrics were accounted for. Reported in Table 7 are both unstandardized coefficients, b, and standardized coefficients, β. The unstandardized coefficients are useful for interpreting how a one-unit change in the independent variables is related to changes in the dependent variable directly. For example, in Model 1, an increase of one activity completed per week on average was related to an increase in children’s gain score on the app-test of 0.37 points. The standardized coefficients are useful for interpreting the relative strength of the relationships between independent variables and the dependent variable in the models. For example, in Model 1, the number of activities a child completed per week explains the greatest amount of variance in their gain score on the app-test, with a beta value of. 47.

Qualitative data gathered from parent interviews and focus groups provided interesting contextual information on how children used the app independently and how they extended their learning beyond their experiences in the app. These qualitative data provided further insight into the question of what relationships, if any, exist between children’s individual in-game choices and their English learning outcomes. Some extracts from parents’ comments are highlighted below:

In the beginning, I was almost always right beside him, and I thought I could enliven things and I would say things like, “The cat is cute,” but I gradually started to feel that I was in the way, and so I would make dinner while he was doing it and I would really only say things like “your eyes are too close to the screen” (parent of a first-grade child).

Well, it was only during the first time that I had to open the application and sit with him. Then after a week, he began doing it independently. Usually, he does it before going to school for 15 minutes. It was like he developed a habit of doing the app every morning as part of his morning routine. Sometimes, he would call me for help, and that’s when I gave him encouragement. Or, when he didn’t gain any stars, I try to empathize and tell him that it’s difficult even for me, creating a shared understanding of what’s happening at the moment (parent of a second-grade child).

Parents also shared anecdotes on how their children demonstrated greater interest in learning English by creating opportunities to practice English outside of the app and how they tried to support their children’s English development.

Recently, we got to walk home together. On our way home, she would ask me, “What’s ‘this’ or ‘that.’” I taught her that for things nearby, we use “this,” and for things far away, we use “that.” So, together with the words memorized from the app, she would construct phrases using “this is” or “that is” and continue in that way for around 30 minutes until we reached home. And this happens every day (parent of a second-grade child).

She says in English what she understands in English when we go out, so when we go to the zoo, she says what the animals are called in English. My oldest is in the fifth grade, and now she is learning English, too. These days, the three of us speak broken English among ourselves. We don’t use long grammatical phrases. However, we do say certain greetings, such as 2-word set phrases like “Good Morning,” and she once asked me a question in English in the bathroom (parent of a second-grade child).

When making crafts, I’ve seen him sometimes use English words when drawing pictures and asking me, “What is this?” and saying the words in English rather than Japanese. Another thing is he chatted with the teacher in English class, and he began to watch anime and English cartoons. He also looked at maps of the world to see where English could be used (parent of a second-grade child).

Additional feedback from parents further suggested that the type of autonomous learning experience designed to be engaging and offered through using ABCmouse English contributed to their children’s development of English skills.

She really likes animals, so she seemed to enjoy doing words and even long sentences involving animals. There is some sort of animal or pet park, and every day after finishing the unit, she would open it. It talked about what kinds of food certain animals eat, for example, and she loves that. It was a way of having fun that was just right for my daughter’s age (parent of a second-grade child).

He was having so much fun with it. He really enjoyed playing on the screen, answering the questions in a certain period of time. There was also a voice recording feature to check his pronunciation, and he would get some good scores. Sometimes he wouldn’t get a good score. But I guess that gave him more motivation to keep working on it as well. So, instead of getting demotivated, that gave him another reason to keep recording (parent of a second-grade child).

The ability to check the playback of her recorded voice kept her very focused. It really was that ability to use her own voice in the learning process and listen back to see how well she did that seemed to really amuse her (parent of a first-grade child).

Discussion

This study of young Japanese children’s experiences learning English through an app-based self-guided digital game provides evidence that research-based apps like this one can be effective. Such apps can augment learner autonomy because they are designed to facilitate learning in a motivating and self-directed environment for children. Additionally, the data presented here show that such apps can be used in informal nonclassroom learning settings to improve L2 English learning outcomes, as the treatment group in this study demonstrated significantly greater gains in their English language learning outcomes compared to the control group. These gains were mirrored in both the app-test developed by the L2 specialists who created the program and the Eiken Junior English assessment—the most widely used English proficiency assessment for this demographic. The dovetailing assessment results also corroborate the curriculum’s usefulness to the target population, as the game-based structured lessons and exploration activities provided significantly greater Eiken Junior score gains for users than for the “business-as-usual” participants.

In fact, the regression analysis revealed that after controlling for children’s prior English language knowledge, the amount of progress that children made on the learning path portion of the game was a significant predictor of their learning gains. This finding is not surprising since the learning path of the game exposes children to activities targeting specific linguistic forms incrementally presented based on L2 developmental sequence and assessment research. These findings also suggest that it may be children’s progress through the game on the app (i.e., the number of activities they completed) that most directly impacts their learning, rather than the amount of time they spend in the app or the number of days they play each week. In other words, how often or how long students spend on the app may be of secondary importance; as long as they are making progress in the game, they are learning.

We also found that children who spent more in-game time on learning activities progressed further than those who spent more time in other areas. Interestingly, replaying prior activities in the exploration area was also a significant predictor of children’s learning gains. The exploration area of the game was designed as a motivational feature for children to freely replay activities that they had enjoyed, such as animation videos, games, etc., with the added benefit of consolidating knowledge that they had gained previously in the game and increasing automatization. In this case, the repetition of activities the children enjoyed provided opportunities to both build and attend to language, an important prerequisite to noticing a gap between what they want to understand or produce and their ability to do so. Noticing gaps in one’s linguistic repertoire is considered a key tenet of adult second language acquisition (e.g., Robinson, Reference Robinson2013), although younger learners are thought to process linguistic input at lower levels of attention, like apperception (e.g., Gass, Reference Gass2017) or detection (e.g., Tomlin & Villa, Reference Tomlin and Villa1994), and to build knowledge through repetition. Future research will seek to better understand why children replayed certain games, with one source of data being stimulated recall interviews carried out in the L1, with replayed activities as the stimuli. For the purposes of the current study, however, the association between replaying games and learning suggests that children were taking advantage of the self-directed features of the game and that these features were beneficial.

The qualitative data from the parent surveys, interviews, and focus groups also suggest that self-guided games like the app used in the current study provide exposure to different varieties of native-speaking pronunciation models than they might have at home, opportunities to self-evaluate progress, as well as a choice of learning activities, all of which can enhance young learners’ English language skills individually and collectively. Another noteworthy finding from the qualitative parent data was the extent to which parents noticed their children making use of their English outside of the app games. Parents cited instances in which their children initiated the use of English in everyday interactions, an indicator of their children’s interest in the language as a topic of conversation or a point of pride (e.g., receiving a compliment from an English teacher). Motivation has been studied extensively in the general SLA literature, and research has shown that it can vary or fluctuate depending on factors such as the language activity, the learners’ level of interest in a topic, or their rapport with interlocutors in particular settings (Csizér, Reference Csizér, Lamb, Csizér, Henry and Ryan2019; Henry et al., Reference Henry, Davydenko and Dörnyei2015; Moskowitz et al., Reference Moskowitz, Dewaele and Resnik2022). Although child L2 motivation is relatively less studied than its adult counterpart (cf. Nikolov, Reference Nikolov1999), app-based games, such as the one investigated in this study can, when carefully designed, present a clear motivational draw for young (and older) children by facilitating directed motivational currents (DMCs; Dörneyi, Reference Dörnyei2014; Muir, Reference Muir2020)—enjoyable periods of high involvement and engagement in an activity that lead learners toward a highly-valued endpoint. Parents noted, in particular, that the app’s activities appealed to their children’s interests (e.g., animals), leading to increased investment in achieving environmental (e.g., earning stars) and content-based (e.g., achieving pronunciation points) goals. These findings corroborate other work on self-determination theory (SDT), which posits the importance of autonomy, capability, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000; Reference Ryan and Deci2020), with support from parents, educators, and learning environments, as appropriate (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci, Ryan, Liu, Wang and Ryan2016; Núñez & León, Reference Núñez and León2019; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2017). In the context of the app in this study, participant users were able to exercise autonomy in their choice of activity types (e.g., structured lessons, exploration environments), which previous research has shown engenders feelings of ownership and volition, which, in turn, tend to lead to successful learning experiences as well as to a sense of competence and relatedness (Jang et al., Reference Jang, Kim and Reeve2016). This dynamic may also provide some explanation for the overall relatively consistent app usage of the children in this study, which contrasts some previous research findings (e.g., Chen et al., Reference Chen, Shih and Law2020; Chen, Reference Chen2023), most of which focused on older learners (e.g., Rama et al., Reference Rama, Black, Van Es and Warschauer2012; Roohani & Heidari Vincheh, Reference Roohani and Heidari Vincheh2023; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Newgarden and Young2012) or teachers’ perceptions about learners’ gaming behaviors (e.g., Blume, Reference Blume2020, see also York et al., Reference York, Poole and DeHaan2021).

This study both corroborates the findings and extends a prior experimental study of an earlier version of the app with five- and six-year-old children in China (Bang et al., Reference Bang, Olander and Lenihan2020). That study similarly demonstrated that the app was useful in helping young learners develop their English language skills while also increasing interest, motivation, and confidence in learning English. Games, when carefully designed, can contain features conducive to learning that were attended to in the app tested in the current study (see Butler, Reference Butler, Reinders, Ryan and Nakamura2019). These include setting clear goals, providing immediate feedback, challenging learners, and fostering collaboration and interaction. As demonstrated in the findings of this study, digital game-based language learning can be harnessed for L2 language learning as more young learners grow up with digital games as a natural part of their lives. The evidence supporting the effectiveness of apps like these is timely, given that the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath brought to light an increasing need for high-quality, effective English language learning resources that can be used at home or elsewhere, independent of the school context.

Pedagogical implications

Although this study was designed to investigate extramural language learning via game-based play outside formal classroom settings, there are, nevertheless, pedagogical implications vis-à-vis classroom-based learning settings. For example, when considering the integration of self-directed play in early childhood education (e.g., in learning or activity stations in the classroom; Vidal-Hall et al., Reference Vidal-Hall, Flewitt and Wyse2020), DGBL apps, such as the one investigated here could fruitfully be integrated into the existing play infrastructure for additional learning opportunities for young children given the positive findings of the current study.

Limitations and avenues for future research

The current study set out to better understand whether and how a game-based app impacted second language learning in young children in a foreign language learning context outside the classroom. Pre- and posttest data were collected using Zoom, and one of the recruitment criteria was access to a desktop or laptop computer to conduct the language tests, in addition to access to a mobile device on which children could use the app. This inevitably eliminated a segment of the population and may have introduced some bias in the sample. Moreover, Zoom itself, at the time of data collection, was not a very familiar tool for many of the young children and thus may have inhibited some of their responses given that they were interacting with adults unknown to them via a medium with which they were not very familiar. Although their adult caretakers were close by, they were asked not to intervene in providing answers for the children, their abilities during both pre- and posttests may have been impacted by the medium.

This study involved collecting in-game tracking data of children’s play behavior along with pre- and posttest data. Linking what children are doing in games to consequential differences in learning patterns has clear implications for both theory and practice. Understanding the patterns in the children’s play behaviors (i.e., the sequence of activities and the proportion of time children spent in different types of structured versus unstructured learning activities) can be helpful for recommendations about how app-based games can be designed to encourage more children to adopt specific play behaviors conducive to learning. Our future work focuses on these aspects of the study. We also note that while this particular app has been examined in China and Japan, the findings might not hold true in different cultural contexts, and thus, tests in other settings are warranted. It is also important to note, as discussed in the methodology section, children were either given ABCmouse English and asked to continue with what they usually did (or didn’t do) or asked to continue whatever they usually did (or didn’t) do in relation to English language learning and were not asked to use the app. In other words, some children in both groups might have been taking English classes. This was a conscious design choice made to investigate the effect of an app on the regular lives of children. However, it could have impacted the results. Despite these limitations, the current study has shown that the app facilitated learning and that the different ways in which children engaged with the app were associated with different learning patterns. There is currently a great deal of interest in apps of all kinds, along with cautions from groups and countries about overreliance on technology and the potentially negative impact of screen time. This study has pointed to the learning benefits that can be derived from carefully designed apps such as the one tested here, which was designed based on L2 research findings and SLA principles.

Additionally, because the app (and this research project as a whole) is aimed at identifying helpful educational tools to improve learning outcomes, it is possible that despite the research team’s best efforts to avoid any coercion to play the game, some parents—eager to maximize exposure to educational content for their children—may have pushed their children to use the app, regardless of instructions from the research team not to do so. This may have contributed to the consistently high level of usage of the app throughout the 16-week period of the study, in contrast to other studies on language learning apps that have documented more sporadic use (e.g., García Botero et al., Reference García Botero, Questier and Zhu2019). Future research could explicitly ask parents at the end of the study if this was the case.

This study provides an early attempt at examining how young language learners may benefit from using educational apps outside of classroom settings. Since there are a limited number of studies with young language learners, mostly with small samples, it would be beneficial to conduct this type of study with larger samples to identify and share more generalizable patterns. Similarly, as this study investigated second language learning of English, future research could explore how the app-driven language development of young learners of languages other than English compares to those in this study and similar studies. Additionally, this study tested just one app, but a variety of apps of this nature exist, not all of them designed based on L2 research, and examining how different apps perform can help us identify the relative importance of features that are associated with learning.

Also, while the current study employs a randomized control design with the control group being “business-as-usual,” without the app, future research might include a second control group comprised of children who receive similar amounts and types of English input in a self-guided context, but without the resources and affordances of the application. While it may not be possible to achieve a truly balanced design, balancing—to the extent possible—variables such as language exposure, input, and output would help us better understand the effectiveness of the application versus that of other resources outside the classroom.

As mentioned in the discussion, an extension of this study could include a stimulated recall interview to help better understand why and when young learners decide to replay (or not) activities within the application. With one of the affordances of game-based learning being self-directed features, it would be illuminating to ask young learners (in their L1s) about their reasoning for the choices they made when using the different features found within the language learning application. Obviously, answers would be limited by the ages and cognitive abilities of the children, but from the perspective of educational app developers, it is vital to understand how these data, as well as in-game tracking data of the children’s play behavior, might be linked to consequential differences in learning gains. Analyzing the patterns in children’s play behavior (e.g., the sequence of activities and the proportion of time children spent in different types of structured versus unstructured learning activities, the choices the children make in choosing between structured and unstructured activities) would be helpful in developing game mechanics in apps aimed at encouraging more children to adopt specific play behaviors that are conducive to positive language development.

Another positive affordance of technology-assisted language learning is that technology can be more accessible than language classes or teachers for many. However, while educational technology is becoming increasingly more accessible every day, there are still populations who do not have access to the necessary technology to participate in the study.

Notwithstanding these inevitable limitations in the current study, it sheds light on an underresearched population (i.e., young learners) in the growing field of technology-assisted language learning. Given the findings in favor of app-based learning, continuing to investigate how language learning applications can best be utilized for language development will likely benefit the field of second language acquisition.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Erin Lenihan, Cheryl Tsuyuki, and Kirsten Olander, who were employees of Age of Learning, Inc. at the time of the study and played significant roles in developing the curriculum and instruments for the study. Thanks are also due to Erin Fell for help with editing; the assessors who were undergraduate and graduate students at International Christian University in Japan; and the leadership at Age of Learning, Inc who facilitated the study through financial support of the data collection in Japan but also allowed the authors the full autonomy in data analysis and write-up, given their commitment to the integrity of research.

Data availability statement

The experiment in this article earned an Open Materials badge for transparent practices. The materials are available at https://osf.io/vj6h9/.

Appendix A

Linguistic Objectives Addressed in the English Language Learning App

Appendix B

Sample items from the app-test

Vocabulary identification

-

• The assessor tells the child, “I will play an audio. Listen to the English word. Choose a picture that matches the word that you hear.” The assessor then plays the audio.

-

• If the child shows no response after about 10 seconds, the assessor prompts the child once, saying “What number is ‘robot’?” and plays the audio once again.

-

• Assessor records the number of the picture child selected.

-

• If the child does not respond after the prompt, the assessor clicks on “no response” before moving onto the next question.

Listening for meaning

-

• The assessor tells the child, “I will play an audio. Listen to the English conversation and choose a picture that matches what you hear.” The assessor then plays the audio.

-

• If the child shows no response after about 10 seconds, the assessor prompts once (in L1), saying “I will play the audio again. Listen carefully to what they are talking about,” and plays the audio again.

-

• The assessor records the number of the picture child selected.

-

• If the child does not respond after the prompt, the assessor clicks on “no response” before moving onto the next question.

Pronunciation

-

• The assessor says, “Let’s listen to some English and try repeating it,” and plays the audio file.

-

• If the child does not respond, the assessor marks “no response.”

-

• If the child responds in L1, the assessor prompts the child once in L1, “Can you please speak in English?”

-

• Assessors use the following scale to score the pronunciation (each description is written in the assessor’s L1):

-

○ Incorrect: The word uttered is not recognizable. It is virtually impossible to know what the target word is.

-

○ Mostly incorrect: The word uttered is pronounced with mostly incorrect sounds. The target word is difficult to recognize.

-

○ Mostly correct: The word uttered is pronounced with most of the correct sounds. The target word is recognizable.

-

○ Correct: The word uttered is the correct pronunciation of the word. There is no confusion about what the target word is.

-

Speech production

-

• The assessor plays the audio or asks (in English) “What are these?”

-

• If the child shows no response after about 10 seconds, prompt the child with the same question once.

-

• If the child responds in L1, the assessor asks in L1, “Can you tell me in English?”

-

• The assessor marks the question correct if the child says “shoes.” The assessor records the question mark if the child says that they do not know the answer or the child’s response if they say something other than “shoes.”

Conversation

-

• The assessor says to the child in L1, “Look at this picture and listen to the English question. Please try to answer in English. If you don’t know how to answer, just say ‘I don’t know.’”

-

• The assessor says to the child in English, “There are many things in the picture. I see a doll. What do you see?”

-

• If the child shows no response after 10 seconds, the assessor asks the question in Japanese as a scaffold.

-

• If the child responds in Japanese, prompt the child once in L1, “Can you say it in English?”

-

• The assessor enters the child’s response in the field provided.

-

• If the child does not respond (after the prompt), the assessor marks “no response.”