Today, the Court of Federal Claims plays a significant role in American politics, though its importance is largely overlooked. Created in 1855 as the U.S. Court of Claims (USCC), the court lacked a precise constitutional role or structure for much of its history, as it vacillated between Article III and Article I status. Today its role is much clearer: It is an Article I specialized court with national jurisdiction that is primarily authorized to hear money claims against the federal government, including claims concerning contracts, bid protests, military and civilian pay, taxes, Native American claims, takings issues, congressional reference cases, and even vaccine injury claims.Footnote 1 Beyond its extraordinarily diverse jurisdiction, the sheer dollar value of the claims heard in this court makes it an important actor in American politics. For fiscal years 2014 through 2019, the court heard an average of $80.6 billion per year in claims against the government and awarded an average of $759 million per year to those claimants.Footnote 2 Its considerable power—built deliberately over time—makes it an important case study in administrative state development.

Congress created the Court of Claims to address the problem of handling private claims against the government. These claims typically consisted of things like disputes over veterans pensions, allegations of breach of contract, and damages to property. During the mid-nineteenth century, these claims took up such an enormous share of Congress's time that its members routinely complained that claims were preventing Congress from dealing with pressing public business. By 1832, Congress devoted two full days each week in session, Fridays and Saturdays, to deal with the private business of individual claims against the federal government. During these early decades of the Republic, Congress doubted whether the national government could waive sovereign immunityFootnote 3 and whether it could delegateFootnote 4 its Article I Section 9 treasury power to a new tribunal to award these monies. Therefore, Congress initially sought to handle the problem of private claims with legislative and administrative tools. Indeed, Congress only opted to create this specialized court after its earlier attempts to dispose of the claims problem had failed. Even after settling on something it called a “court” as the appropriate fix for this pressing problem, whether the new institution was in fact a proper court within the constitutional framework of Article III was sharply disputed for more than a decade.

The debate focused on whether the USCC could have the authority to render final judgments and to award monies out of the Treasury to claimants suing the federal government. Because of these concerns, the USCC had an ambiguous, hybrid, quasi-judicial role for its first few decades. On the one hand, this tribunal took on an advisory role for the executive branch akin to present-day Article I administrative courts. The tribunal also adjudicated and investigated cases referred to it by Congress, alleviating congressional committee workloads. On the other hand, the USCC was composed of “judges” who were appointed by the president, confirmed by the Senate, and served life terms akin to those staffing Article III courts. Moreover, the U.S. Supreme Court heard appeals directly from the court for most of its history as the statutory language mandated. The “institutional hybridity”Footnote 5 of this body, however, caused Congress and the Supreme Court to regularly grapple with crucial questions of sovereignty immunity, the delegation and separation of powers, and the nature of judicial power in designing and structuring the USCC.

This article examines this early episode of institution building when Congress and the Supreme Court debated these structural questions most seriously. Because of the constitutional uncertainty surrounding the USCC and the growing problem of private claims, members of Congress had to revise their interpretation of their own power: whether and how money could be drawn from the Treasury to pay aggrieved claimants,Footnote 6 and whether it could delegate this constitutionally derived power to an independent court. We argue that the development of the USCC—and its contested constitutionality—presents one of the earliest examples of the expansion of national administrative capacities. The court's incremental and pragmatic developmental path differs significantly from traditional models of American state building, which emphasize the role of ideological and electoral motivations as key drivers of development. In tracing the early development of the USCC, we demonstrate how the new arrangement was institutionalized through a process of constitutional constructionFootnote 7 and interbranch dialogue.Footnote 8 The difficulties raised by the fledgling USCC—and the lengths to which legislators and judges went to resolve them—provide new insights into the interbranch dialogue during the mid-nineteenth century that shaped the USCC into the consequential institution that it is today. In particular, we argue that the development of the USCC is best understood as an episode of creative syncretism,Footnote 9 motivated by the need to solve a practical administrative problem.Footnote 10

1. Institution Building and American Political Development

The recurring question Congress faced—and the central question of this article—was how could Congress resolve the workload problem brought on by private claims? How Congress addressed these administrative issues tells us about the tension between the American constitutional framework and state capacity as the American state developed. The problem of private claims raised questions about how to expand state capacity in light of the dominant understanding of separation and delegation of powers. This practical problem of dealing with claims against the government resulted in changes in how Congress and the courts understood their own constitutional authority and roles within the separation of powers system as it related to suits against the government. Congress ultimately decided to cede power to a new and unique Court of Claims, but to do so, it first had to reimagine its own constitutional powers and the practice of sovereignty. Thus, the central scholarly question—with implications for the American political development (APD) field—is why did Congress resolve the problem in the way that it did? This USCC case study therefore fits into a larger story about the origins of the modern American state, suggesting that the American state was modernizing considerably earlier than much of the APD literature suggests.

Studies of American state building have long emphasized the lack of national administrative capacity until the passage of the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. Theodore Lowi describes the American state before 1887 as primarily based on patronage policies.Footnote 11 From 1800 to 1937, Lowi claims that apart from “a few constituent policies (treaties with France and England, creating the courts, setting up departments), every legislative output at the federal level was distributive (patronage) policy.”Footnote 12 By the New Deal era, however, the rise of congressional delegations of power to the executive and bureaucratic agencies became so frequent that “[a] whole new jurisprudence was developed in order to justify it, and the federal judiciary adjusted itself accordingly.”Footnote 13 In Lowi's view, the American administrative stateFootnote 14 was absent until the New Deal, reflecting a prevailing view of American administrative development “that the national government only began to exercise significant influence over the lives of most Americans in the early twentieth century.”Footnote 15 Building on this work, Skowronek moved the conversation away from America's statelessness during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Instead, he emphasizes how a “state of courts and parties” filled this administrative void at the national level, and the national state was “uniquely configured, well-articulated, eminently serviceable, and manifestly successfully” in governing through the federal judiciary and national parties.Footnote 16

These accounts of the American state, however, rely on the idea that the administrative state is “legally significant only to the extent that it creates specialized agencies to regulate private conduct.”Footnote 17 In conceiving the administrative state so narrowly, APD scholarship has overlooked important variations in early American state building, development, and enforcement. This article shifts the focus from regulation of private conduct to the USCC—an early example of congressional delegation of power to a specialized agency, one created to deal with congressional workload problems rather than with regulatory issues. We trace the institutional development of the USCC from the Revolutionary period through its creation in 1855 and its immediate aftermath, and we examine the congressional debate surrounding how to deal with its administrative problems and whether Congress had the constitutional authority to delegate its power to this institution in the first place. This case study joins revisionist scholarship like Mashaw's, which recognizes “the extremely limited record of judicial review of administrative action and the special forms that this review took in the early Republic . . . to free us from the tyranny of our current judicio-centric legal culture.”Footnote 18 Indeed, the varied solutions Congress proposed and implemented to deal with the backlog of private claims prior to the USCC's 1855 creation were solely within the executive bureaucracy or Congress itself. This article's central question—why did Congress establish the USCC as a way to resolve the workload problem brought on by private claims?—also joins other APD scholars in conceiving state formation “as a significant developmental problem.”Footnote 19 We argue that a key part of the state formation story is Congress's pragmatic change in its understanding of sovereign immunity and the separation of powers so it could solve mundane administrative problems.Footnote 20

The court's long, incremental, and pragmatic developmental path is also inconsistent with traditional views of American state building. Traditional approaches emphasize the role of ideological and electoral motivations as key drivers of punctuated equilibrium models of development, which view change as proceeding along a path of relative fixity then pierced by regime-shattering “constitutional moments.” By emphasizing the incremental nature of constitutional development of the USCC, this article joins recent studies that understand the Constitution as an ongoing project involving creative syncretism and slow institutional change.Footnote 21

To understand the creation of the USCC, this article fits together two theories of institutional development, (1) constitutional construction and (2) creative syncretism, and argues that neither alone could explain this story. The USCC was forged through interbranch dialogues among the judiciary, executive departments, and Congress. Political elites had to modify their core beliefs about the Constitution and the separation of powers to arrive at any kind of workable solution. Therefore, the institutional development of the USCC largely rested not only on U.S. Supreme Court rulings but also on what WhittingtonFootnote 22 calls “constitutional constructions”—nonjudicial, political actors bringing their own interpretations of the Constitution to bear on the building of this tribunal. Whittington's theory speaks to the separation of powers and interbranch dialogue at the root of the USCC's emergence. Scholars have also noted the ways in which political forces contribute to both institution buildingFootnote 23 and the meaning of the Constitution. Indeed, the “governance as dialogue movement” rejects “the notion of either total legislative supremacy or total judicial supremacy in favor of a much more complicated and nuanced, continuous process of interaction among the institutions.”Footnote 24 Interbranch dialogue played an important role in the development of the USCC. As we describe later, such dialogue is observed in the continued calls by presidents, such as Millard Fillmore and Abraham Lincoln, for Congress to reform the handling of private claims. The dialogue is also found in the Supreme Court's decision in Gordon v. United States,Footnote 25 which forced Congress to fully empower the USCC as an Article III court if Congress wanted the court to have the constitutional authority to hear and decide claims with any kind of finality. Thus, the constitutional constructionFootnote 26 and ensuing interbranch dialogue only happened because a long-running administrative failure made clear the need for institutional development.

Administrative efficiency issues largely motivated the USCC's development, suggesting a “creative syncretism”Footnote 27 account of institutional change. Berk and Galvan's theory of creative syncretism understands institutions phenomenologically, examining the experience of those within the institution and emphasizing the pragmatism embodied by those operating within an institution. Rather than treat institutions as exogenous constraints on behavior, this theory stresses the mutability of institutions and the ability for actors to continuously recombine and decompose institutional structures as they see fit. Creative syncretism offers a useful framework for understanding the USCC because it is an institution whose development resulted from the pragmatic experience of those living under the inadequate and inefficient rules governing claims adjudication. Indeed, as Sheingate notes, “Syncretic change is a process of creative problem solving, contributing to the creation, maintenance, and disruption of social structure”—a phenomenon at play in the USCC's creation, as we will show.Footnote 28

Ultimately, this case study of the USCC shows that while both constitutional construction and creative syncretism explain parts of the story, neither in isolation can explain this developmental episode. Members of Congress's evolving understanding of separation of powers and delegation of authority can be fruitfully understood through the lens of constitutional construction theory. This constitutional construction was necessary only because of the performance-based need (solving the private claims workload crisis) for institutional development and reform. Congress's needs and preferences led it to create new constitutional arrangements through an iterative dialogue with both administrators and the Supreme Court to enable that syncretism. In the end, neither theory alone is enough to help us understand the court's development; rather, one only sees the full picture by looking at how both theories interlock and interact.

2. Constructing the Court of Claims

Dealing with claims against the government justly and efficiently was already a centuries-old problem by the time the USCC was created in the mid-nineteenth century. Presidents throughout the nineteenth century recognized this problem. “The difficulties and delays” in settling private claims against the U.S. government, President Fillmore said in his 1850 Annual Message to Congress, “amount in many cases to a denial of justice.”Footnote 29 Congress had too much “business of a public character” for it to be spending time on private claims against the government. He recommended “a commission to settle all private claims” and appointed a solicitor to represent the federal government. Just five years later, Congress established the USCC. Yet that did not even come close to mitigating the persistent flood of financial claims against the government placed before Congress because the court had no real authority to settle any of these claims with finality; Congress still retained review power. Indeed, President Lincoln, in his 1861 Annual Message, noted that “by reason of the war,” claims had spiraled even further out of control. He therefore put forth a more pointed recommendation to Congress than Filmore had, calling on Congress to relinquish its power: It would be far too engaged “with great national questions,” and furthermore “the investigation and adjudication of claims in their nature belong to the judicial department” because it is “the duty of government to render prompt justice.”Footnote 30

In this section, we describe the development of institutional responses to this problem from the Confederation forward, in context with their British antecedents. As we will show, creating a court to deal with the problem of claims was far from Congress's first choice. Dealing with claims administratively was strongly preferred for more than a century, due to then-dominant understandings of the nature of sovereignty in the separation of powers system and to more straightforward path-dependence. However, the claims repeatedly overwhelmed the national government's early administrative and legislative remedies. These repeated failures ultimately led the period's leading statesmen to rethink the balance of power and rearrange core institutions, continuously decomposing and recombining the institutions of claims administration, to reflect this new understanding. Ultimately, the practical problem of dealing with claims against the government produced a new way of understanding sovereignty in the United States and the separation of powers, with Congress ceding power to a new and unique Court of Claims. We trace the early development of this new court and demonstrate how the new arrangement was institutionalized through a process of constitutional construction.

2.1 Claims During the Revolutionary War and Early Republic, 1780–1835

The nonjudicial approach to settling private claims in the early Republic is a consequence of America's colonial history and inheritance from England, whose doctrine of sovereign immunity extended “at least as far back as the feudal system.”Footnote 31 But other European and South American models allowed for their federal government to be sued in one way or another.Footnote 32 When the American colonies won their independence in 1783, they inherited a long-recognized tradition of petitioning the king, which not only left the power to adjudicate claims in the legislative branch but also adhered to a version of sovereign immunity that prevented many claim settlements. Seventeenth-century England saw the king and Parliament clash over control of finances, and in the wake of rebellion in 1642, Parliament took over many of the country's finances. The struggle continued for decades until the Glorious Revolution of 1688 definitively affirmed Parliament's power over the treasury and appropriations. This power, however, produced some unintended consequences: Whenever there was a surplus of appropriated monies in the Exchequer, these treasury officials were not allowed to turn over the monies to the king. As a result, members of Parliament used these extra resources to settle the private claims of their constituents. Yet, no evidence exists that Parliament ever created a workable, official system to deal with these claims.Footnote 33

The first representative assembly in the colonies, the Virginia House of Burgesses, created three standing committees, including one on “public claims” in 1680.Footnote 34 Over a century later, after independence from England, the states continued this legacy of dealing with claims legislatively rather than judicially. The Articles of Confederation stated that claims against the national government could only be paid “out of a common treasury” when “allowed by the United States in Congress.”Footnote 35 Moreover, since the Articles of Confederation created no national judiciary or executive, it foreclosed the long-held common law procedure in England whereby a person having a claim against the Crown could petition for the right for judicial review of said claim.Footnote 36 Under the English system, when the king received a petition, he could, at his discretion, refer the petition to a court, and the citizen would have a trial.Footnote 37

Without an executive or a judiciary, and possessing widespread distrust in the superintendent of finance whom Congress “suspected of using public office for private gain,”Footnote 38 the Confederation Congress established a three-member Board of Treasury to help manage the country's finances in 1784. Yet claims adjudication remained firmly in the legislative branch. The board's chief task was settling Revolutionary War claims, but it lacked independence. The Confederation Congress concerned “itself with even small matters of finance and directed the board at almost every point.”Footnote 39 Congress referred the claims brought before it to this three-member board for further examination. Typically, the board required written documentation, heard evidence, and then reported its recommendations to Congress, which had sole authority to authorize a payment to a claimant. Claim amounts in this period were typically small, such as claims for reimbursement requests for cattle used by the military and for compensation for homes and tools destroyed to prevent them from being used by the British enemy.Footnote 40

A few years later, during debate over constitutional ratification, anti-Federalists raised concerns over how the new Constitution would settle claims. In his essays on Article III, Brutus worried about “the evil consequences that will flow”Footnote 41 from claims being settled judicially rather than legislatively. He warned:

It is improper, because it subjects a state to answer in a court of law, to the suit of an individual. This is humiliating and degrading to a government, and, what I believe, the supreme authority of no state ever submitted to. The states are now subject to no such actions. All contracts entered into by individuals with states, were made upon the faith and credit of the states; and the individuals never had in contemplation any compulsory mode of obliging the government to fulfill its engagements.Footnote 42

In response, Alexander Hamilton detailed in Federalist 81 how the long-held concept of sovereign immunity would prevent Brutus's fears from being realized: “It is inherent in the nature of sovereignty not to be amenable to the suit of an individual without its consent. . . . Unless, therefore, there is a surrender of this immunity in the plan of the convention, it will remain with the State.”Footnote 43 Early on, then, even before the Constitution was ratified, questions of claims against the government were put on a largely legislative path.Footnote 44 Moreover, during ratification debates, Revolutionary War debt drove states to insist on state sovereign immunity protection, so they could potentially avoid claims against their governments,Footnote 45 which produced the same inefficiencies seen at the federal level as well as a patchwork of administrative and legislative claims commissions.Footnote 46 Like the federal government, state governments dealt with claims through legislative determination as evidenced by standing committees on claims existing in half of the states in 1790.Footnote 47 At the time, too, state courts often affirmed legislatures’ jurisdiction over claims.Footnote 48 Thus, in the early Republic and continuing onward, claims were seen as a financial question and not a legal one, but the creation of a federal judiciary raised questions about how to proceed.

Upon adoption of the Constitution on March 4, 1789, Congress created a similar method of settling claims as it had under the Articles of Confederation. Section 5 of the Act establishing the Treasury Department gave review authority to auditors within that department,Footnote 49 but despite this shift to the executive branch, Congress retained final say, and thus appeals from the Treasury Department could be brought before it. Congress legislated that the auditor would receive “all public accounts,” certify the balance, and transmit them “to the Comptroller for his decision thereon.”Footnote 50 If a claimant was dissatisfied with the outcome, he or she could appeal to Congress within six months, and Congress could refuse to fund the comptroller's decision, if Congress was in favor of a claimant. Thus, even under the newly created Constitution, the settlement of claims remained in the legislative branch.

Nevertheless, there remained some institutional ambiguity over the settlement of claims, noted early on by James Madison in 1789 when Congress debated the Treasury Department's creation and the ways it would handle claims. In discussing the comptroller's role, Madison noted: “It seems to me that they partake of a Judiciary quality as well as Executive. . . . The principal duty seems to be deciding upon the lawfulness and justice of the claims and accounts subsisting between the United States and particular citizens: this partakes strongly of the judicial character, and there may be strong reasons why an officer of this kind should not hold this office at the pleasure of the Executive branch of Government.”Footnote 51 In this way, how U.S. institutions would process claims remained unclear.Footnote 52

Despite the ambiguity of the new Treasury Department's role, Congress did not relinquish substantive control of claims adjudication either to executive, judicial, or quasi-judicial/executive bodies between the 1790s and late 1830s. Because “colonial legislative tradition ran too deep” over appropriations and thus claims adjudication, Congress continued its legislative dominance over claims. Congress enacted its first private claims bill on September 29, 1789, and by this time, the legislative-centric model of adjudicating claims was widely accepted. Congress heard 704 petitions that year, and it responded to them by referring them either to the relevant cabinet secretary in the executive branch or to a special congressional committee for examination and then recommendation to the full Congress.Footnote 53

The inherited tradition of legislative handling of claims was one reason the American approach to handling claims developed as it did, but that is not the only reason. There were also strong theoretical reasons justifying the legislative approach, especially the doctrines of sovereign immunity and separation of powers. The doctrine of sovereign immunity dated far before the United States was even an idea. Born from the monarchical principle that the “sovereign can do no wrong,” sovereign immunity was embedded in the design of the Constitution. As Hamilton said in Federalist 81, for example, “it is inherent in the nature of sovereignty not to be amenable to the suit of an individual with its consent.”

Two early Supreme Court cases touched on these issues of sovereign immunity and separation of powers: Hayburn's Case Footnote 54 and Chisholm v. Georgia. Footnote 55 With respect to Hayburn, Congress passed a 1792 statute regarding pension claims arising out of the Revolutionary War, and it tasked the federal circuit courts with reviewing these claims and certifying their findings to the Secretary of War. Five of the six justices on the Supreme Court objected to serving in this capacity because the statute gave an implied power to the Secretary of War to revise or to refuse to implement the courts’ reports. Sitting as judges of the three circuit courts, these five Supreme Court justices wrote opinions in the form of letters to President George Washington, which claimed that the statute imposed nonjudicial duties on the courts and thus violated the separation of powers. Hayburn represents an early example of the federal judiciary maintaining that its judgments must be final and could not be amended by executive or legislative branches.

Just a year later in 1793, the Supreme Court decided Chisholm, which centered on whether citizens could sue states in federal courts without a state's consent. Here the Court held that Georgia could be sued without its consent in federal court, holding that the states did not possess sovereign immunity when being sued in federal court. Issuing their opinions seriatim, the justices left open whether the federal government was afforded sovereign immunity in similar suits. Similarly, the justices said nothing about whether states can be sued without consent in state courts. The legacy and importance of sovereign immunity can be seen in the passage of the Eleventh Amendment following the immediate backlash to Chisholm. The swift rejection of Chisholm and the quick passage of the Eleventh Amendment demonstrates the power of sovereign immunity held at the time. The Eleventh Amendment's passage is often hailed as a states’ rights victory, but it also garnered support from the Federalists because it ensured the perpetuation of a legislative approach to claims adjudication, diminishing the possibility that the judiciary would begin to determine claims made against governments (especially the federal government) without consent.Footnote 56

During this time, Congress adopted two policies to perpetuate the legislative approach to claims adjudication. First, the House of Representatives created a Committee of Claims on November 14, 1794. The House defined the committee's jurisdiction expansively: over “all claims against the United States, where money was the relief prayed for,” where claimants sought to be “discharged from any liability,” whenever the claim referred to “public lands,” “private claims,” and “all pension claims.”Footnote 57 Second, to the extent Congress did delegate claims adjudication authority, it was to institutions like the Treasury over which it could exert extensive oversight and maintain control of appropriations. While the Treasury Department handled most routine contract claims, Congress retained appeals authority from Treasury's decisions and maintained control over a special commissioner appointed to deal with claims arising out of the War of 1812.Footnote 58 Notably, Congress refused to delegate any authority over claims adjudication to the judiciary.

Congress's reliance on legislative modes of claims resolution, then, was grounded in both historical practice and theory received from colonial experience. There was also a more uniquely American rationale for legislative handling of claims: the doctrine of separation of powers. The Constitution gives Congress alone the authority to spend money. Thus, many congressional representatives believed that ceding the power to appropriate funds to settle claims would be unconstitutional. That is, if courts were given the power to decide claims against the federal government, then “some feared that . . . Congress would be required to make payments in accordance with the court's determination and that such a procedure would clearly violate article I, section 9.”Footnote 59

During this period, Congress maintained virtually full control over claims adjudication, delegating authority only to nonjudicial bodies, including the Treasury, where it could control decision making and appropriations. Thus, Congress clung closely to a view of the separation of powers that permitted only it to control appropriations. While the Treasury Department heard the majority of routine contract claims, Congress typically heard appeals from Treasury determinations and most noncontract claims outside the scope of the narrow Treasury authority.

Toward the end of this period, in 1838, the Supreme Court affirmed and asserted Congress's power over claims adjudication as seen in Kendall v. United States.Footnote 60 In Kendall, the Court considered an 1836 act that required the Postmaster General to credit and honor contracts in the full amount determined by the solicitor of the treasury. Nevertheless, Amos Kendall, President Jackson's newly appointed Postmaster General, refused to honor the contract amount negotiated by his predecessor. Thus, the DC Circuit Court ordered him to obey, and he still refused. Congress then enacted a law requiring Kendall to follow the recommendations of the solicitor of the treasury. Kendall again refused, arguing that the congressional act was a constitutional violation on the power of the executive branch. Finally, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled against Kendall, holding, among other things, that Congress could assign ministerial duties to executive officers and that the federal judiciary had the authority to enforce these duties through writs of mandamus.

Shortly thereafter, in Reeside v. Walker, Footnote 61 the Supreme Court clarified Kendall by holding that a claim could only be paid when Congress provided a specific appropriation per Article 1, Section 9, emphasizing Congress's sole authority over appropriations. Reeside held that a claim could only be paid if a claimant specifically petitioned Congress “for an appropriation to pay [the claim].” And, “if Congress after that makes such an appropriation, the Treasury can, and doubtless will, discharge the claim without any mandamus. But without such an appropriation it cannot and should not be paid by the Treasury.”Footnote 62

Thus, through the early Republic, the colonial legacy of legislative handling of claims, as well as the widely shared view of sovereign immunity, created a background presumption against judicial resolution of claims against the government. This was reinforced by Congress's interpretation of its own constitutional powers. However, by no means was the belief in the doctrine sovereign immunity shared by all. As early as Chisholm v. Georgia, Justice Wilson's seriatim opinion disparaged “state sovereignty,” which “has assumed a supercilious preeminence above the people who have formed it.” And the doctrines that deal with the “supreme, absolute, and incontrolable power of government” “degrade” the people.Footnote 63 Wilson's opinion cast doubt on the sovereign immunity of both states and the federal government, but the Eleventh Amendment quickly headed off any legal and political implications found in his opinion.

Nevertheless, Justice Wilson's argument was the exception that proved the rule; the majority of lawmakers did not believe that the federal government could waive its sovereign immunity. It is difficult to say exactly why, but in his historical examination of the doctrine, George Pugh attributes “the adoption of the doctrine in this country … [to] the thought habits of common law lawyers, and by the very natural desires of state governments to avoid payment of their vast debts.” Indeed, over sixty years later, in 1860, despite members of the House Committee on the Judiciary urging that the USCC should be placed under Article III judicial control and sovereign immunity should be waived, it still took years more persuading to make these changes. The Committee on the Judiciary argued, “when the government enters a contract, or engages in any pecuniary transaction with an individual, it to that extent divests itself of its sovereign character, and assumes that of a private citizen.”Footnote 64 That the committee made this suggestion in 1860 demonstrated the thorny and controversial nature of sovereign immunity and Article III jurisdiction in debates over the creation and development of a Court of Claims.Footnote 65 These factors set the United States down a path that strongly hewed to legislative control over claims and resisted judicial solutions to a growing workload problem.

2.2 Claims in the Antebellum Period, 1838–1855

By the early decades of the nineteenth century, this legislative-centric system was under considerable strain. Congress could not keep up with the claims being filed, and it had a significant problem rendering decisions in over 90 percent of these claims. The problems of maladministration and inefficiency began to crystallize around 1838. That year, the House Committee of Claims examined these problems closely and presented its findings: “the accumulation of private claims has been so great, within the past few years, as to burden several of the committees of Congress.”Footnote 66 The committee highlighted the incredible caseload increase between the first three Congresses (2,317 cases from 1789 to 1795) and the 22nd–24th Congresses (14,602 cases from 1832 to 1837). Figure 1 demonstrates this remarkable increase.

Fig. 1. Number of Claims Cases in Congress, 1789–1795 versus 1832–1837.

Source: Data from this graphic come from the Rockwell Report, “Claims Against United States,” in U.S. Congressional Serial Set (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1847), 1–48, 32.

During this time, Congress could not act on 3,302 of the 8,655 (38 percent) private claims bought before it.Footnote 67 The Board of Commissioners for Settlement of Claims Report (Rep. No. 730) concluded with the rampant inefficiency Congress faced: “These cases now burden Congress,” and the delay amounted to “a denial of justice.” “To remedy the evil,” the committee highlighted two reforms previously suggested: “enlarge the powers of the accounting officers” or “constitute a commission, to whom claimants shall be permitted to appeal in all cases where the accounting officers reject a claim.” The Committee ultimately recommended only one of these reforms: establishing a board of commissioners.Footnote 68 Notably, a board of commissioners would not be part of the judicial branch because “the framers of the constitution did not think proper to waive the privilege of sovereignty, and permit suits to be brought against the United States.” Additionally, since the courts were “closed against enforcing the payment of claims due from the United States, other suitable tribunals should be established” such as a board of commissionersFootnote 69 housed in the Treasury. The growing volume of claims, then, was putting considerable strain on Congress, but members felt constrained by the doctrines of sovereign immunity and separation of powers.

Congress adopted neither of the solutions offered by the Committee of Claims but instead continued to muddle along with what it recognized to be an inadequate system of claims adjudication. A decade later, the situation devolved into crisis, and the Committee of Claims issued another report, authored by the committee chairman, Representative John A. Rockwell (W-CT).Footnote 70 The House tasked Rockwell's committee “to inquire and report whether any and what further legislation is required in relation to the claims of individuals against the government of the United States.”Footnote 71 Rockwell's report detailed the statistics of private claims from the 22nd–29th Congresses, totaling sixteen years of data. From his committee's report, Rockwell drew a number of conclusions, which he conveyed to the House the following year: Claimants were not often given a hearing, no interest was allowed on claims (despite the fact that many, if ever resolved, took fifteen years to be acted upon), serious claims where a considerable amount was at stake were almost never approved, and “unfounded and fraudulent”Footnote 72 claims were difficult to recognize because these claims were ex parte with no representation on behalf of the federal government to cross-examine and investigate. Thus, Rockwell's report aimed “to show the evils of the present system,” which was plagued by “unparalleled injustice, and wholly discreditable to any civilized nation.”Footnote 73

Echoing the earlier 1838 report of the Committee on Claims on the same issue, the Rockwell Report noted the workload and efficiency problems in dealing with claims. During this ten-year period, “16,573 petitions of private claimants to the House of Representatives and 3,436 bills reported, 1,796 passed the House” and of those, only 910 passed through both Houses.Footnote 74 Rockwell also noted the sheer amount of time claims took away from “public business,” with “one-third of the whole time of one House of Congress is devoted, under the rules, to private claims.”Footnote 75 The report concluded, “It is grossly unjust that this defective system, which the government adopts as the only one for claims against them, should be charged to the account of honest claimants, and that they should suffer because the tribunal, which the government says is the only one to which they can appeal, is wholly inappropriate to the discharge of such duties.”Footnote 76

The 1848 Rockwell committee report highlighted two alternative paths forward. One recommendation was for a set of commissioners, but whose decisions were “declared to be final” and not merely recommendations. The second recommendation, though, arose from review of the successful claims systems found within the judicial branch of various European states: delegating decision-making authority to the federal courts. Rockwell personally favored this solution, but noted, “the committee did not think that all the subjects brought to the consideration of Congress were proper subjects of decision by judicial tribunals.”Footnote 77 Indeed, these same considerations caused some in Congress to protest relinquishing finality over appropriations even to commissioners. Ultimately, Rockwell's committee proposed the same solution presented in 1838: a board of commissioners of three people to be appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, centrally located in the capital.Footnote 78 Importantly, these commissioners would not render final decisions, but instead would make recommendations to Congress on the resolution of claims. The committee report makes very clear the extent to which even strong advocates of reform felt compelled to work within a legislative framework because of prevailing views about the requirements of sovereign immunity and separation of powers.

A year after his committee's report, Rockwell introduced this proposal as a bill. Under the prevailing system, Congress had to enact private bills to pay debts to claimants, if the current administration rejected the claims. The House spent one-third of its time considering private bills “in addition to countless hours consumed in committee” trying to deal with these claims. Rockwell concluded that “no other civilized country of the world had such an outrageous system.”Footnote 79 Despite these problems, Congress refused to approve Rockwell's 1849 bill for two central reasons. First, the proposal came during a period of rising populist sentiment,Footnote 80 and thus Congressional proposals to hand over responsibilities to a new set of unelected judges or commissioners faced genuine opposition. For example, Representative Orlando Ficklin (D-IL) argued, “If these gentlemen were to hold office during life, why not make the offices hereditary, and let the oldest sons succeed to their fathers?”Footnote 81 But Representative James Bowlin (D-MO) offered even harsher criticism about the commissioners, which centered on the prevailing interpretation of Article 1, Section 9, and Treasury power: that they would decide cases “by some vague idea of justice in their own minds. The treasury was to be thrown open, and thus was the money, wrung by taxation from the hard earnings of the people, from their toil and sweat, to be squandered upon plunderers and favorites around the Capitol.”Footnote 82 Second, beyond these populist critiques, other representatives objected for legal reasons concerning Article III jurisdiction issues. Representative William Strong (D-PA), for example, who later served a distinguished career on the U.S. Supreme Court, maintained, “no claim against the Government was a case arising ‘in law and equity,’ The party did not found his claim against the Government upon any principle of law or equity, and certainly these claims were not cases which arouse under the Constitution or the laws of the United States.”Footnote 83 Even Rockwell's report and committee ultimately concluded that many of the claims issues brought before Congress should not be heard by the judiciary.

Despite a consensus emerging that the current system was “about the worst that could be devised,”Footnote 84 change was not forthcoming. By 1848, it was clear that Congress had a serious workload and maladministration problem, but the question remained as to what could be done. Congress debated this question off and on—and presented a variety of solutions (none of which came to fruition)—over the next seven years until it created the USCC.

In maintaining the status quo, Congress hewed closely to its “legislative model”Footnote 85 of claims adjudication where it retained final control over appropriations, but the focus on a board of commissioners located in the capital laid the foundation for a centralized system to be created in the next decade. A centralized system created a greater likelihood that decisions “would be more favorable to the government's interests than the decentralized generalist alternatives,” and it had long been advocated in some form or another.Footnote 86 As early as 1824, for example, Senator John Chandler (D-ME), pushed against the legislative model and argued for a board of commissioners’ ability to give claims cases to the federal courts because “the juries who were called to try them, would invariably be biased in favor of the individual claimants, especially as the claimants would be their neighbors.” Others also advocated for a centralized board of commissioners because it allowed for greater administrative capacity: The board “should be in this city,” said Maine's other Senator, John Ruggles (DR-ME), because “all the information on the subjects before them would be at hand.”Footnote 87 Chandler and Ruggles exemplified how institutional actors, facing significant obstacles, attempted to create new rules and interpretations to problem-solve administrative issues.

Yet even vocal critics like Representative Strong noted that the 1848 Rockwell Report “proposed a remedy for an evil, the existence of which was universally admitted” and that it was rare that “unanimity of sentiment was found in this Hall.”Footnote 88 In that same year, Congress created the Mexican War Claims Commission (which lasted from 1849 to 1851)—a three-member board of commissioners who sat for two years and who the president appointed—to adjudicate claims arising under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Still, more permanent and wider reaching solutions languished in Congress, despite the urging of President Fillmore and other Congressmen noting corruption problems. Fillmore stated in his Annual Message in 1850 that many “unfortunate creditors” had been “unavoidably ruined” by “denials of justice.” He therefore urged Congress to establish “some tribunal to adjudicate upon such claims,” encouraging experimentation and creativity within the legislative branch.Footnote 89

Ultimately, between 1849 to 1855, nine bills were introduced in Congress to alleviate the workload associated with adjudicating claims against the national government.Footnote 90 The possible solutions centered on four options: a board of claims (of some sort), changes in legislative committees, expanding authority of “accounting officers,”Footnote 91 or allowing the federal courts to adjudicate claims. In 1852, Representative Brown of Mississippi presented a legislative solution that would reconfigure the internal workings of how Congress processed claims: a “General Committee of Claims” comprising fifteen members of Congress “to stand as a kind of appellate court . . . authorized and required to review the reports of other committees, and only to ask the action of Congress in case they approve such reports; and, in the second place, to report a bill of the payment of private claimants.”Footnote 92 When introducing his resolution, Brown couched it in opposition to an agency solution like a board of claims, noting that it would “increase executive patronage.” And, since such an agency would have no authority to appropriate money from the Treasury, he argued that appropriating “an aggregate sum” would “delegate to the board a power over the public funds which belongs exclusively to Congress.”Footnote 93 Others were skeptical this would make any difference at all and, instead, suggested that the government “throw open the doors of the courts of justice, and let every man who has an honest claim against the government”Footnote 94 seek redress in courts. Some others resisted a court-based solution because it would force the government to “be compelled by the juries of the country to pay millions which this House has not paid, and which preceding Houses have not paid.”Footnote 95

One of these nine bills, debated in 1852, revealed that these maladministration problems were growing into issues of corruption and fraud. The Senate created a special committee to inquire into “abuses, bribery or fraud,” and further consensus finally emerged to remove claims adjudication out of Congress.Footnote 96 Noting the widespread corruption of the Mexican War Claims Commission, Senator Hale said, “If there were three millions of money to be disbursed by the government without there being corruption in the transaction, it would form an exception to the general rule.”Footnote 97 Some senators disagreed on the corruption accusation, but nevertheless, they accused the commission of “injustice”: Those that are awaiting claim hearings, Senator Solomon Downs (D-LA) said, “charge that injustice has been done [and] there is a mystery about the matter; that the investigation has not been as public as such things ought to be.”Footnote 98

Debates like these continued in the Senate and in the presidency. In 1854, Senator Brodhead (D-PA) moved to have a report of “The Mexican Frauds” submitted and printed. Senator James Bayard Jr. (D-DE), who had sat on the committee that created the report, then summarized parts of it, noting that in the course of their investigation, the committee found some witnesses in cases “superinduced so strong a conviction of fraud.”Footnote 99 In considering a bill to “establish a board of commissioners for the examination and adjustment of private claims,” other senators noted that because Congress neglected to appoint an impartial government attorney, it produced “evils” now “deemed fraudulent,” and this would not have been allowed “if there had been a faithful officer of the Government.”Footnote 100

In sum, we have seen that between 1838 and 1855, a consensus emerged that Congress had to, in some form, move claims adjudication out of the institution, but the debate centered on what body would handle claims and what powers it would wield. There were roughly two sides of the dispute over how to resolve the claims problems: Some argued that a new tribunal should be a fully independent court (or administrative body), and others sought a commission that would take evidence from claimants and then make a recommendation to Congress as to whether to adopt or reject a private claims bill. The reasoning behind each of these solutions rested on both pragmatic and constitutional arguments.

The commission's suggested solution was presented by Representative Rockwell, the chair of the Claims Committee, first in 1849 and then in 1854. Senator Brodhead advanced a nearly identical proposal in the Senate. Both Rockwell's and Brodhead's proposals maintained that Congress had ultimate control over claims. Ultimately, the Rockwell and Brodhead camp made constitutional arguments for the position that an advisory commission and not a court must deal with claims. When debating Rockwell's proposal in 1849, Representative William Strong (D-PA) argued simply, “no claim against the Government was a case arising under ‘law and equity’” under Article III of the Constitution and therefore the courts did not have jurisdiction over these cases.Footnote 101 Later, in response to Brodhead's bill in 1856, another Pennsylvania representative, David Ritchie (W-PA), argued that sovereign immunity prevented courts from adjudicating claims. That is, according to Ritchie, Article III's construction of judicial power ensured that the United States could not be a defendant: “The judicial power of the United States, no matter in what court or by what form of words it may be vested, does not extend to cases in which the United States are defendants … in cases where the United States are defendants, whatever it may be, is no part of the judicial power of the United States.”Footnote 102 Thus, suits against the federal government could not fall under the power of Article III courts. In presenting his bill proposing an advisory commission, Brodhead shared the same sentiments as Strong and Ritchie: “It is very doubtful whether we have power under the Constitution to waive sovereignty and to authorize the Government to be sued either in ‘law or equity.’”Footnote 103

Opponents couched their rebuttal in both constitutional and pragmatic terms. On the latter, in response to Rockwell's 1849 proposal to create a board without finality, Representative Joseph Ingersoll (W-PA) said the institutional design of Rockwell's plan contained “fatal errors.” It would still lead to “the same unsatisfactory tribunal to adjudicate your cases that you are dissatisfied with now, and are endeavoring to get rid of. It recurs with no substantial change, having only the doubtful advantage in preliminary of the judgment of a board of strangers, instead of the report of a board of fellow-members.” Ingersoll then asked rhetorically, “Where is the harm in submitting the claims to final determination before a proper board? It will have the advantage of permanency.”Footnote 104 Ingersoll rested his reasoning, like other opponents, on the sheer pragmatic reality that Congress should be taken out of the process altogether because it was incapable of addressing claims expeditiously and efficiently. Others in Ingersoll's camp grounded their position constitutionally, arguing that the Constitution allowed another institution to have finality and jurisdiction over claims and related appropriations. For example, Representative Richard Meade (D-VA)—in rebutting Strong's argument detailed above—argued that the Constitution permits courts to hear claims because “the Constitution of the United States contemplates cases in which the United States may be a party defendant or a party plaintiff; it makes no exceptions. What authority has the gentleman from Pennsylvania [Strong] to limit the jurisdiction?”Footnote 105 Meade thus argued that since the Constitution gave courts jurisdiction over cases where the United States was a defendant, these claims cases were justiciable under Article III.

During this period Congress settled on some type of administrative “board” solution that would leave Congress with final say over claim awards. This preference came from a widespread belief that sovereign immunity and the separation of powers system enshrined in the Constitution required legislative handling of claims, and not from any belief that Congress was actually best suited to do the job. Even so, a vocal minority of members, like Senator John Pettit (D-IN) and Representative Meade, advocated transferring full authority over to the courts. Majorities in Congress, however, rebuffed court advocates like Pettit largely because, as Senator Brodhead noted, giving courts “final and conclusive” judgment “would be placing the public Treasury at the disposal of the courts contrary to the meaning of the Constitution.”Footnote 106 Time and again in this period both concerns about separation of powers and Congress's interpretation of its treasury power proved a stumbling block over solving growing delay in claims adjudication.

2.3 Creating the Early Court of Claims, 1855–1856

While the claims issue grew to crisis levels, the question remained: What was Congress going to do about all these problems and inefficiencies? Ultimately, members of Congress were forced by the scope of the claims problem to rethink the nature of sovereign immunity, reconsider the constraints imposed by the separation of powers system, and finally contemplate a judicial solution to the crisis. This debate presented next reflects a legislature divided on this question by issues of constitutional meaning and practicality—but not by partisanship or region, as might be expected in this period.

This debate eventually spurred the 1855 statute, which created the USCC. That statute had its beginnings as a proposal on December 6, 1854, when Senator Brodhead introduced a bill “to remedy an evil which has been a crying one for the last twenty or twenty-five years.”Footnote 107 As a member of the Senate Committee on Claims, he had become familiar with the repeated failures of claims adjudication proposals, and so he consulted with other members of the Claims Committee; by December 18 the bill was opened for debate on the Senate floor.Footnote 108 The debate centered on whether the court should be fully independent or if it should issue advisory opinionsFootnote 109 or reports to Congress for final decision. Importantly, the final bill “did not clearly address” this “critical issue” of judicial finality.Footnote 110 The construction of the Court of Claims nicely illustrates how practical necessity can force actors within the relevant institutions to reimagine theoretical constraints on their authority. It also shows, though, how iterative and contingent the process is, and how the power of the theoretical considerations shapes actors’ behavior.

During the Senate debate on December 6, 1854, Senator Brodhead summarized three institutional solutions to the claims issue: “enlarge the powers” of the Treasury, “enlarge the powers of the judiciary,” or create some agency or board of commissioners. Brodhead's proposal, like the report in 1848, advocated a board.Footnote 111 Brodhead, in a brief paragraph immediately following the list of the three proposals, noted that the Treasury solution was “pretty much abandoned” and “dangerous.” Expanding the judiciary's power received a slightly longer treatment, but ultimately, Brodhead said, “It is very doubtful whether we have power under the Constitutions to waive sovereignty and to authorize the Government to be sued,”Footnote 112 echoing previous sovereign immunity arguments. Like members of Congress previously, Brodhead also claimed of the judicial solution, “It seems to me that it would be placing the public Treasury at the disposal of the courts contrary to the meaning of the Constitution.”Footnote 113 Senator Robert Hunter (D-VA) agreed, arguing it would give “too great a power” to the courts if its decisions could “draw money directly out of the Treasury.” While Senator Hunter called his solution a “court”—“that the United States should have a regular attorney, that its proceedings should be open like those of any other court”—he would not have provided it with “final or conclusive jurisdiction” over amounts to be paid to claimants.Footnote 114 Ultimately, Brodhead's bill proposed a confusing amalgam of an agency and a court. It proposed appointing three commissioners, at a salary of $4,000 each, with advice and consent from the Senate. Some aspects of the institution seemed judicial. The commissioners would enjoy a lifetime tenure, and the procedures resembled judicial ones: It had “power to take testimony in behalf of the Government; will have the time, means, and opportunity to get at and report the facts of each case,” but Brodhead explicitly noted, “I have not made the decision of the board final in any case.”Footnote 115

As the debate over Brodhead's bill continued into the next day, some senators objected to the futility of the proposal and debated whether to call this institution a commission or a court and whether its members would be judges or commissioners. Senator John Weller (D-CA) proposed an amendment to strike out the word “court” in Brodhead's bill and insert “board of commissioners” and to make appointment to this commission based on a period of years rather than during good behavior as Article III stipulates. Weller advanced this amendment because he believed that what was contained in Brodhead's bill was “no court—it is not a judicial tribunal— in the meaning of the third article of the Constitution, and therefore the judges may not necessarily be appointed during good behavior.” Effectively, Weller's amendment simply sought to identify the institution for what he thought it was (and what it would actually become in practice): a legislative court under significant congressional control. Some, like Senator Albert Brown (D-MS), agreed and argued that the bill “does not advance us a solitary inch in the progress of business, unless it be taken for granted that the reports of the court will be infallible, and must necessarily be indorsed [sic] by the two Houses of Congress.” Brown noted that Brodhead's bill—regardless of the terminology and appointment during good behavior—“does not accomplish” either the goal of relieving congressional workload or of offering remedy to private claimants because the bill, ultimately, left Congress the power to approve all claims’ appropriations.Footnote 116 In other words, Brown realized that without judicial finality over decisions and money to claimants, Brodhead's bill did little, if anything, to alleviate the case workload.Footnote 117 Like Brown, Senator Stephen Douglas (D-IL) sought a truly independent court because only that would lead to a lasting effect: “calling this tribunal a board of commissioners would imply that it was only to take the place of a committee, and to report facts. Now, I want an adjudication which I should deem binding on us. . . . I want an adjudication in which I could put the same credence that I would give to a decision of the Supreme Court of the United States.”Footnote 118

Nevertheless, the Senate rejected Weller's amendment, defeating it by a vote of 24–16.Footnote 119 The pushback came from a group of senators who did not see it as necessary to clarify the institution's status because they assumed, despite conflicting Articles I and III constitutional identities, that the Court of Claims would still have great autonomy, which would enable it to significantly reduce Congress's claims burden. Many of these senators, such as Hunter of Virginia, simply assumed that “this court will entitle itself to the confidence of Congress, and will have so much of the confidence of Congress, that in general its decisions will not require revision; that the cases requiring revision will be the exception and not the general rule.”Footnote 120 While Brodhead's bill retained its Article III language of “court” and “during good behavior,” Brown's objections proved prescient and Hunter's proved wrong.

This lively debate highlights the creative syncretism that informed the ultimate creation of the USCC. Congress sought to handle its claims problem by “altering old institutions and recombining them with new proposals,” which, in Brown and Douglas's proposal, was an independent court.Footnote 121 The debate over Brodhead's bill centered on whether to create a fully independent court or an administrative commission that would simply report its conclusions to Congress for final approval.Footnote 122 The debate resulted in Senator Brodhead proposing to appoint a committee composed of Senators Jones (W-TN), Hunter, Clayton, and Clay (D-AL) to look further into the issue.

By December 18, 1854, Brodhead's select committee settled on the compromise first presented earlier in the month by Senator Hunter: an institution called the “Court of Claims” would hear claims against the national government. It would comprise a three-judge panel with commissioners dispersed around the United States to gather evidence and take testimony. Judges would be appointed by the president with advice and consent of the Senate and serve “during good behavior” per Article III, Section 1 of the Constitution. Congress left the difficult questions unanswered, namely, the degree of finality the court had in its decision making. Congress retained final say, ergo this 1855 body acted more as an agency than as a court because Congress continued to cling to the “legislative model” wherein Congress still retained significant control over monies.Footnote 123 The House approved this bill, and Congress created a Court of Claims on February 24, 1855.Footnote 124

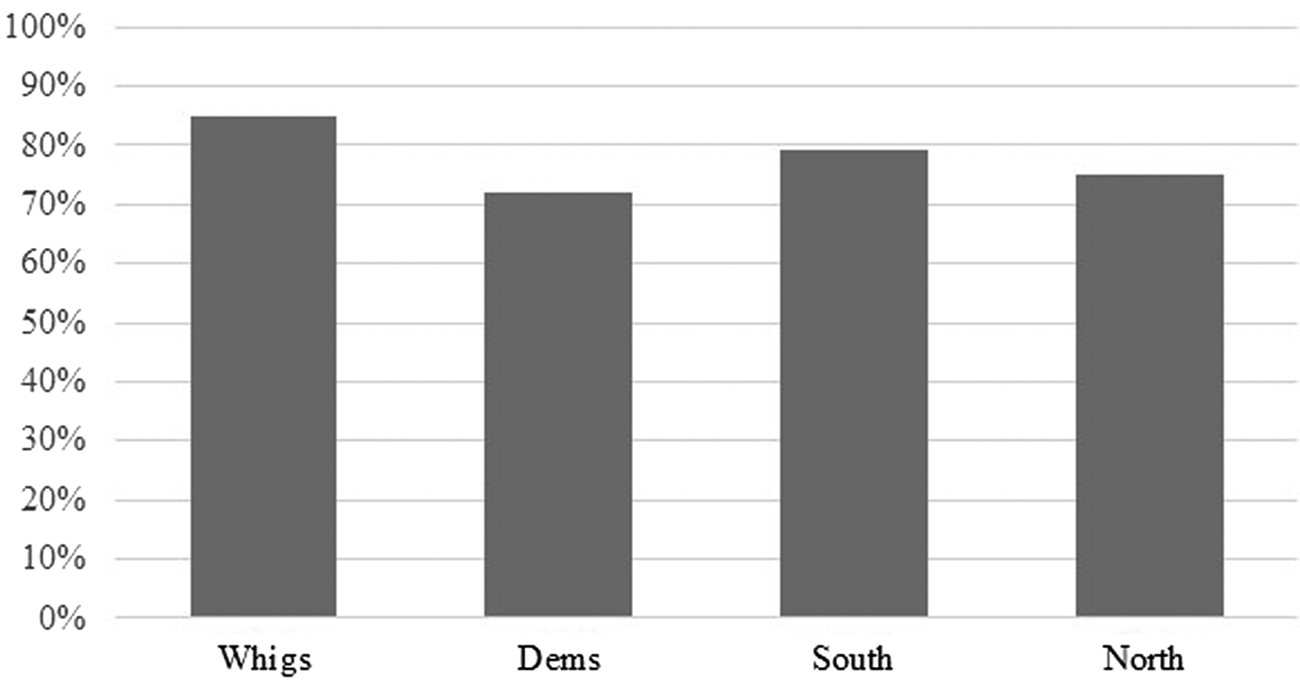

The final vote in the House on this bill was 150 yeas to 46 nays. Figure 2 presents the distribution of the House vote on the Court of Claims bill. This figure clearly demonstrates that the bill had robust support across partisan and regional lines.Footnote 125 The Senate passed it without a division vote recorded.Footnote 126

Fig. 2. Percentage of House Yes Votes on 1855 Statute, by Group.

Source: Vote totals found in the Congressional Globe, 33rd Congress, 2nd Sess. (1855), 909. Demographic data of House members were gathered from Joel D. Treese, ed., Biographical Directory of the American Congress 1774–1996 (Alexandria, VA: CQ Staff Directories, 1997).

The new law required the court to “keep a record of their proceedings” and present these proceedings to Congress at the “commencement of each session of Congress.” In its presentation of materials to Congress, the court also had to “prepare a bill or bills” for those cases in which a decision was favorably made on the claimant's behalf, and “if enacted” by Congress, “would carry the same into effect.”Footnote 127 The House thus interpreted the statute's language as requiring de novo review by Congress of all claims, which made the USCC merely an advisory body.Footnote 128 Yet, the USCC had an entirely different view of its power than Congress did. In its first term, the court did not mince words or shy away from asserting its power. In Todd v. United States (1856),Footnote 129 Chief Judge John Gilchrist declared his court's finality:

The language of the 1855 act does not authorize us to regard this tribunal as possessing any other qualities than those which properly belong to a court. . . . We do not think that Congress, by establishing this court, intended to constitute a council to advise them what course it would be honest and right, or expedient, for them to pursue in any given case. They meant, as the title of the act denotes “to establish a court for the investigation of claims” to ascertain the facts in each case, and the legal rights and liabilities arising from those facts.Footnote 130

In addition to Gilchrist's declaration of finality, he also lobbied on behalf of the USCC in an attempt to establish more power and autonomy for his institution. In his June 23, 1856, report to the Senate, he reiterated his opinion in Todd, telling the Senate, “The court has not regarded itself as a council to advise Congress what was just and equitable.”Footnote 131

Beyond the court's purpose in relation to Congress, Gilchrist shared pragmatic administrative problems, which made his court's duties impossible to fulfill. He commented that Congress's object “was to ensure the award of equal and even-handed justice to the claimant,” but “with the present force that object cannot be accomplished as it should be.”Footnote 132 Gilchrist specifically noted that the sole solicitor established by the 1855 statute “however experienced and eminent [could] properly represent and protect the interests of the government. The cases are so numerous, his duties are so harassing, and his labors so unceasing, that this is entirely impracticable.”Footnote 133 Gilchrist's report demonstrated his efforts to engage in judicial institution building similar to the methods Chief Justice Howard Taft deployed before Congress decades later.Footnote 134 Gilchrist died only three years into his tenure so he had far less success in “forging judicial autonomy” than Taft did, but nevertheless, through his opinions and lobbying Gilchrist sought to create a distinguished professional identity and build an institution with autonomy from Congress. Gilchrist's efforts resemble autonomy building, as described by Carpenter, whereby agencies “can change the agendas and preferences of politicians and the organized public.”Footnote 135

Nevertheless, in the words of a former commissioner of the USCC, the original act “established a body which [Congress] designated as a court, but failed to give the new agency power to function as a court.”Footnote 136 That is, the initial act, it turned out, was hardly transformative at all. It was instead, as Crowe put it, a “stopgap measure”Footnote 137—and a poor one at that, as the act left the status quo essentially unchanged. But at the time of its passage, it received praise as a necessary development.Footnote 138 The inadequacies of the act are crucial for understanding this moment of institution building, however, as they show that even as Congress sought to undertake judicial performance-oriented reforms,Footnote 139 prevailing understandings of constitutional requirements stymied them.

2.4 Establishing Finality, 1855–1866

The 1855 act merely made the USCC a fact-finding agency whose conclusions had to be approved by Congress before payments were doled out to claimants. After a few years of practice, “it became apparent that the lack of finality of the decisions of the Court defeated its object,” according to James Hoyt, Reporter of Decisions for the Court of Claims.Footnote 140 Even newspapers reported on the problem of finality in the same year as the act's passage. The Daily Union, of Washington, DC, wrote, “we believe it would have been much better had congress made the decision of the court final and conclusive with some provisions by which a just claim could have been paid out of the treasury without subjecting the claimant to the uncertainty of congressional action.”Footnote 141 Because of this, little had changed in the adjudication and settlement of cases. Thus, a policy question remained before Congress: Should it give claims adjudication to existing federal courts or redesign the USCC from an advisory body to one whose decisions were final (though reviewable by the Supreme Court)?Footnote 142 And very importantly, could it do so?

Although the first option was proposedFootnote 143 in 1860, there was not much support for giving power to the federal courts; again, the specter of sovereign immunity reared its head as some in Congress feared the ill consequences of ceding power to the courts: “If you allow men to sue the Government of the United States” then the country would “have to have a band of itinerant lawyers . . . looking out for and watching after her interests . . . it would be impossible.”Footnote 144 Therefore, in his Annual Message to Congress in December 1861, Lincoln urged further reform. The looming prospect of a tidal wave of war claims for damages arising out of the Civil War led President Lincoln to argue: “It is as much the duty of government to render prompt justice against itself, in favor of citizens, as it is to administer the same between private individuals.”Footnote 145 He went on to say, “The investigation and adjudication of claims in their nature belong to the judicial department . . . it was intended, by the organization of the USCC, mainly to remove this branch of business from the halls of Congress; but while the court has proved to be an effective and valuable means of investigation, it in great degree fails to effect the object of its creation for want of power to make its judgments final.”Footnote 146

When Congress debated a bill with Lincoln's suggestions in 1862–63, much of the debate centered on the finality of judgments and sovereign immunity. In the House, Representative Albert Porter (R-IN) introduced a bill out of the Judiciary Committee to solve the finality problem. He argued against claims of sovereign immunity and advocated for the court to have finality: “In every great nation in Europe there is a judicial tribunal which decides upon claims against the Government; and especially is this the case in Great Britain. Claims refused by the executive department are referred to that tribunal, and to its decision the king himself has to submit.”Footnote 147 Porter's bill offered more autonomy and finality to the Court of Claims.Footnote 148 Specifically, he noted that the court's “jurisdiction is made final and conclusive” except where Congress “by joint resolution, specially declare [certain claims] shall be disposed of by act of Congress.”Footnote 149 While Porter's bill significantly enlarged the court's jurisdiction to now include “all claims for which the Government would be liable in law or equity if it were suable in courts of justice,” Porter explicitly defended against proposals suggesting that claims be adjudicated in Article III circuit and district courts: “the danger of local influences which might be prejudicial to interests of the Government . . . [and] access can be had to the public archives only at the capital.” There was also the pragmatic impact of the ongoing Civil War, as Porter said, “in most of the southern States no district or circuit courts now exist.”Footnote 150

There was significant debate over Porter's bill in the House where the bill originated. Representative George Pendleton (D-OH) declared his support for the bill as well as for judicial finality, “My only objection to it is that it does not go far enough. . . . I am in favor of bringing [the federal government] into court—a court such as we would be willing to intrust with the administration of justice between individual citizens—compelling it to abide by the judgment of that court.” Later on the House floor, Pendleton also derided the doctrine of sovereign immunity: “I am opposed to the dogma, which has no foundation in justice, that the Government ought not to be sued.”Footnote 151 The most vocal opponent of the bill, Representative Alexander Diven (R-NY), expressed reluctance to relinquish appropriations power to the courts. Diven said Porter's bill—contrary to Porter's claim—in allowing the federal government to be sued “like a corporation or an individual” had “no parallel in any country” and claimed the bill would place “the Treasury of the United States at the mercy of this Court of Claims.”Footnote 152 Despite Diven's objections and Representative Elihu Washburne's (R-IL) motion to table the bill, the House passed the bill without a recorded vote and defeated Washburne's motion 83–40.Footnote 153

The issue of finality took center stage in the Senate's debate over Porter's bill. Senator James Dolittle (R-WI) noted that Congress's finality and discretion over claims “is a discretion which we cannot transfer constitutionally to any other body. . . . It is a discretion which the Constitution puts upon us.”Footnote 154 Dolittle's critics were vocal in their opposition and clear in their position. Senator Browning argued, for example, “We ought to either give some effect to the judgements of this court or abolish it. . . . As it now is constituted, and as its judgments are now regarded, it is a mere mockery of justice.”Footnote 155 Likewise, Senator Edgar Cowan (R-PA) urged some type of finality of court judgment: “I think it would be an absurdity to create a court for the investigation of the claim of a suitor, and yet deny the proper effect and validity of the judgement of the court.”Footnote 156

After the Senate handily defeated a motion to indefinitely postpone the bill by a vote of 29–11, the debate then turned to the issue of giving finality to the court's rulings. Senator William Fessenden (R-ME) proposed an amendment to the House bill to strike out any provisions that made the court's rulings final.Footnote 157 The Senate defeated this amendment by the narrowest of margins: Vice President Hannibal Hamlin cast the final vote to break the 20–20 tie, voting in favor of keeping the finality provision in Section 5 of the 1863 act.Footnote 158 To appease his skeptical colleagues, Senator Lyman Trumbull (R-IL), Judiciary Committee chairman, agreed to amend the bill to diminish the court's jurisdiction to cases arising out of contract dispute with the government only, whereas the House version “gives the court jurisdiction of all claims for which the government would be liable in law or equity.”Footnote 159 In response to Fessenden's objections that the House bill gave “finality to the judgements of the court” and enlarged its jurisdiction, Trumbull assured him that the bill “does not authorize the court to draw any warrant upon the Treasury” and “the Treasury will still be under the control of Congress.”Footnote 160 In addition to winning the battle over finality, Trumbull and his supporters defeated other attempts to preserve Congress's control over the court's rulings. For example, they also defeated an amendment, by a vote of 20–16, to require congressional payment to be paid out of specific appropriations after each individual court ruling rather than appropriating a fixed lump sum at the beginning of the fiscal year out of which all judgments would be paid.Footnote 161 The bill ultimately passed the Senate 23–16.Footnote 162

The debate over Representative Porter's bill in 1863 revealed the growing inefficiency of the 1855 act and the need for real change. Under the 1855 act, claimants had to go to Congress after litigation in the USCC. If a claimant lost, he could appeal to Congress, and if he won, Congress would still have to make the individual appropriation. Therefore, the problem of claims workload in Congress was never resolved. Consequently, despite the vigorous debate in 1863, most members of Congress—with pressure mounting from Civil War claims—altered their interpretation of its role in claims adjudication and chose to empower a more autonomous Court of Claims in 1863.Footnote 163 Most shared Senator Trumbull's perspective that an advisory Court of Claims “was a failure” and that Congress should make its judgments final or delegate full authority to the judiciary.Footnote 164 Trumbull's Judiciary Committee chair counterpart in the House, Hickman (whose committee originally proposed Porter's bill), echoed the same sentiment, recognizing the futility of the court in its then-current form: “We now have no Court of Claims. We have that which has been long called by that name, but which has none of the attributes of a court. It is at best but a committee recommendatory to the standing committees of Congress. It has no power to determine finally any question.”Footnote 165

The legislation passed in 1863 and added two judges to deal with the growing caseload and partially addressed the issue of finalityFootnote 166 by creating a general appropriation of funds that would cover the Court's judgments against the government.Footnote 167 Congress also gave claimants the right to appeal a denied claim to the U.S. Supreme Court for claims over $3,000. This legislation, however, included a last-minute amendment added by a staunch opponent of the Court of Claims, Senator John P. Hale (R-NH). The amendment added Section 14 to the act, providing that no award was to be paid until it had been “estimated for” by the Secretary of the Treasury and Congress validated that estimate and authorized the disbursement of funds.Footnote 168 Hale's amendment ultimately “sabotaged the judicial status” of the USCC, even though both Congress and the court itself appear to have assumed it was in fact an Article III court.Footnote 169