Introduction

The potential for split partisan control is built into the fabric of our system of governance in the United States, intended as a system of checks and balances both within the legislature and across the branches of government (Madison Reference Madison1788). At the federal level, divided government is increasingly common and is tied with the common perception of Congress as an increasingly dysfunctional and unproductive institution. This has motivated a wealth of scholarship on the relationship between split partisan control of the government and legislative gridlock (e.g., Binder Reference Binder2003, Reference Binder2015; Kelly Reference Kelly1993; Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel1998). Although some, such as Coleman (Reference Coleman1999) and Edwards, Barrett, and Peake (Reference Edwards, Barrett and Peake1997), find that government is more productive when controlled by the same party, others have found little to no effect of divided government on legislative outcomes (Jones Reference Jones2001; Mayhew Reference Mayhew1991).

Does divided government mean the democratic process grinds to a halt? Or do legislators look for ways to work around the potential legislative gridlock? Much of the research on divided government focuses on gridlock at the federal level, using longitudinal analyses to examine how changes in partisan control and party polarization impact the ability of Congress to pass legislation. Rather than examining legislative outcomes in the single case of the US Congress, I compare the content of legislation introduced in a cross-section of state legislatures over a period of 117 years. The result is a novel perspective on the impact of divided government in which legislators respond to the increased possibility of gridlock by shifting their efforts to less contentious policy initiatives.

Although legislative enactments reflect the ultimate productivity of the legislature as a whole and are a useful measure of gridlock, the content of legislation introduced provides insight into the priorities and preferences of individual legislators. After all, legislators have finite resources and must decide how to allocate their limited time and attention. As a rational legislator will presumably focus on the policies likely to yield the greatest reward, shifts in a legislator’s portfolio can be interpreted as reflecting changes in a legislator’s expectations. Focusing on state legislative sessions provides significant variation in both bill composition and political environment, which allows me to measure the relationship between divided government and how legislators choose to allocate their limited resources in a wide variety of contexts. The combination of cross-state and historical data provides a more complete picture of how shifts from unified to split partisan control influence the work of legislators than has previously been available.

By demonstrating how the composition of bills introduced changes, I provide a new theory of legislative behavior under divided government that reconciles competing theories of a legislature bound by gridlock and reelection-minded legislators seeking accomplishments. Building on the divided government literature as well as work by Gamm and Kousser (Reference Gamm and Kousser2010) that identifies determinants of bill composition in state legislatures, I demonstrate that while the number of bills introduced remains constant under divided government, there is a significant shift in the content of legislation introduced. When the governor’s mansion is controlled by the opposing party, legislators turn their attention away from efforts to implement statewide policy changes and instead focus on particularistic bills that target specific, distinct areas of the state and directly benefit their own constituents. I argue this is the result of legislators balancing the need for accomplishments to use in their reelection campaign (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974) with the challenges of policymaking on contentious issues under divided government (Bowling and Ferguson Reference Bowling and Ferguson2001; Clarke Reference Clarke1998). By focusing on district-specific legislation, legislators can maintain productivity as these bills are generally viewed as less contentious and allow for shared credit-claiming with the executive.

I begin by providing an overview of the existing literature on divided government, followed by a discussion of why legislators may choose to focus on particularistic legislation that benefits their constituents. I offer a theoretical justification for why an increased focus on particularistic legislation is a rational choice for a reelection-minded legislator and test this theory using a dataset of 165,000 bills from 13 state legislatures over seven sessions between 1880 and 1997. I show that divided government does not have an effect on the number of bills introduced in a given legislative session, but split partisan control of state government results in a decrease in the percentage of statewide bills introduced and an increase in the percentage of district-specific legislation.

Governing through gridlock

Scholarship on the effects of divided government on legislative productivity generally falls into two camps. The first is the traditionalist, strong-party view, in which governments are unable to function effectively under divided government, leading to a perpetual legislative stalemate. Under this school of thought, the American system of government can only be productive when the president and both houses of Congress are controlled by the same party (Ripley Reference Ripley1969). As described by Sundquist (Reference Sundquist1988), “divided government invalidates the entire theory of any party government and presidential leadership” (p. 626). Some scholars even go so far as to declare the gridlock that sometimes results from divided government as one of the fundamental flaws of presidential systems of government (Linz Reference Linz1990).

Examining the effects of unified versus divided government in the US Congress has revealed that “significant” legislation is more likely to be enacted under unified government (Coleman Reference Coleman1999), opposition from the president leads to lower rates of bill passage under divided government (Edwards, Barrett, and Peake Reference Edwards, Barrett and Peake1997), more bills pass by party-line vote under unified government (Thorson Reference Thorson1998), and divided government is associated with more protectionist trade policies (Lohmann and O’Halloran Reference Lohmann and O’Halloran1994) and increased budget deficits (McCubbins Reference McCubbins, Cox and Kernell1991). At the state level, divided government is linked with greater fiscal instability as legislatures are unable to appropriately adjust revenues to respond to changes in the state’s financial situation (Alt and Lowry Reference Alt and Lowry1994; Poterba Reference Poterba1994).

An alternate view, advanced most notably by Mayhew (Reference Mayhew1991), suggests that shared partisan control produces few substantive effects on legislative productivity. A study of congressional investigations and the enactment of “important legislation” over six decades finds no relationship between divided government and either the number of investigations or “significant” laws enacted. Mayhew attributes this finding to the need of members of Congress to engage in credit claiming to win reelection, which supports an overall tendency towards constancy. “If members can believably claim credit for taking the steps to win passage of important legislation, no doubt they will work just as hard at those steps and aim for as much electoral profit in divided times as in unified times” (p. 103).

Similar research has shown that when party polarization and majority party margin are accounted for, there is no substantive effect of divided government on legislative gridlock (Jones Reference Jones2001). Krehbiel (Reference Krehbiel1998) and Brady and Volden (Reference Brady and Volden1998) argue that gridlock is the result of policy preferences of individual legislators and institutional rules and can therefore occur under both unified and divided government. Although divided government may negatively impact legislative productivity under specific circumstances or on particular issues, broader analyses largely support Mayhew’s “no effects” finding at both the state and federal levels (Fiorina Reference Fiorina, Galderisi, Herzberg and McNamara1996; Rogers Reference Rogers2005).

To a large degree, how legislative productivity is measured is a significant determinant of how it is influenced by divided government. Although Mayhew (Reference Mayhew1991) looks at the enactment of “landmark legislation,” Edwards, Barrett, and Peake (Reference Edwards, Barrett and Peake1997) look at bill failures and find contradictory results. Some scholars have challenged Mayhew’s measurement of significant legislation, including Kelly (Reference Kelly1993), who finds that divided government has a significant negative impact on bill enactment when looking solely at legislation that was determined innovative in retrospect. Coleman (Reference Coleman1999) highlights how different measures of significant legislation yield dramatically different results for the impact of divided government. Beyond the challenges of identifying “important” legislation, there is also a question of whether a count of significant bills passed or defeated is an appropriate measure for testing the impact of divided government. The underlying assumption is that more legislation passed is indicative of a more functional legislature, but such measures do not account for the demand for legislation, the scope of bills passed, or their policy impact (e.g., Binder Reference Binder1999; Fiorina Reference Fiorina1992; Saeki Reference Saeki2009).

I contribute to this divided literature by demonstrating that while legislatures maintain productivity under divided government, the effects of split partisan control can be seen at the beginning of the legislative process, when members are deciding what their policy agenda for the session will be. I propose an alternate view of divided government in which the total number of bills does not change, but the composition of the bills introduced in the legislature shifts from broad statewide policies to particularistic district-specific bills as a result of legislators’ perceptions of where they will gain the greatest benefit. Rather than examining legislative enactments and contributing to the ambiguous findings on legislative productivity and gridlock, I focus on the substance of bill introductions. I argue that introductions provide a clear picture of how legislators spend their time under divided and unified government. Given that legislators face many demands on their time, the types of bills introduced represent the revealed preferences of legislators. A shift in the type of bills introduced under divided government is therefore an indication that legislators believe that divided government affects the passage of statewide policy changes.

Even if one subscribes to the view that divided government does not have an effect on the passage of major legislation, legislative gridlock is still a well-documented phenomenon. Whether gridlock is the result of divided government, party polarization, or supermajoritarian rules, a legislator who seeks to change policy will only be successful if he is able to gather the support of a majority coalition of both chambers of the legislature and the chief executive.Footnote 1 Although in many cases this may not be a sufficient condition for policy change, it is a necessary one. As Krehbiel (Reference Krehbiel1998) argues, “policy change requires that the status quo must lie outside the gridlock interval, as defined by the president, filibuster and veto pivots” (p. 47). When the chief executive and legislature are controlled by opposing parties, this is a particularly difficult threshold to meet. Under divided government, “all major policy decisions are now the result of an institutionally structured bargaining process, with each party possessing a veto” (p. 242).

I theorize that when divided control of government makes policy change difficult, legislators will increasingly turn their focus to bills that benefit their local constituents. Many of these district-specific bills have minimal ideological content, and therefore the likelihood of passage should not depend on whether the preferences of the median legislator and the chief executive are aligned. In general, particularistic bills are more narrowly focused, less controversial, and should therefore be easier to pass. At the same time, particularistic bills provide benefits directly to a legislator’s constituents and can fulfill all three of Mayhew’s reelection-seeking strategies. The legislator takes a position on an issue that is important to the local community by introducing legislation, is able to claim credit for delivering a project of local importance if it passes, and has an issue to advertise to their constituents. By shifting their focus to these particularistic bills, legislators can get around the gridlock that would otherwise be created by divided government and still maintain a level of productivity that might not otherwise be possible.

What have you done for me lately?

Particularistic bills are attractive to legislators because they provide a relatively low-cost means to deliver benefits to their constituents. Catering to local needs with particularistic policy is an effective way for a legislator to appear in touch with the needs of the community and provide benefits to the voters, businesses, interest groups, or other local entities that can help the legislator secure reelection (Gamm and Kousser Reference Gamm and Kousser2010). The benefits of these particularistic bills are often more immediately felt by constituents, which also contributes to their appeal for a legislator considering reelection strategies (Ashworth and de Mesquita Reference Ashworth and de Mesquita2006). They may take different forms, from “pork-barrel” construction projects to commemorative bills, but are identified as “particularistic” because they target specific and distinct areas of a state, such as cities, counties, or school districts. On the whole, these district-specific bills are generally easier to draft than new policy initiatives as a result of their limited scope, requiring minimal effort on the part of the sponsoring legislator for a potentially large reward if they are successful in passing the bill.

Consider an analogous example on the federal level – the naming of post offices. Post office naming bills represented 20% of the legislation enacted by Congress between 2005 and 2010 (Kosar and Hairston Reference Kosar and Hairston2011). These ceremonial bills are popular among legislators because they have little cost, both in time and money. As described by Representative Ann Wagner (R-MO), “Every member of Congress should be doing things that are meaningful for their district and their constituents. What this does for the community, it’s amazing. Everyone comes out, you’ve got hundreds of people at the ceremonies. It’s such a moving dedication and a way to come together” (Plautz Reference Plautz2015).

The continued prevalence of particularistic policy bills at both the state and federal level regardless of partisan control demonstrates that legislators clearly value these bills. But why should they be more appealing to legislators under periods of divided government? In addition to being relatively easy to draft and a good way for a legislator to provide a tangible benefit to their constituents, particularistic bills are generally easier to move through the legislative process than broad policy changes. These bills typically contain minimal ideological content and as such do not exist on the traditional left-right policy dimension, which makes them less likely to be held up by partisan gridlock (Gray and Jenkins Reference Gray and Jenkins2019; Lee Reference Lee2009). Dodd and Schraufnagel (Reference Dodd and Schraufnagel2009) provide evidence of this at the federal level, demonstrating that the proportion of laws passed that are commemorative in nature parallels gridlock on salient legislation (as measured by Binder (Reference Binder2003)) and increases under divided government.Footnote 2 A rational legislator is going to devote their efforts to the area where they expect to see the greatest benefit. When statewide policy shifts are difficult to enact because the legislator’s preferences are not in line with the majority in the other chamber or the governor, district-specific legislation is an attractive alternative.

The primary challenge is then convincing a majority in the legislature to support a bill for which the costs are borne by all, whereas the benefits are only received by a single or small group of districts. Distributive policymaking in majority-rule institutions tends to be consensus-based (Fiorina Reference Fiorina and Crecine1981) and governed by the decision rules of universalism and reciprocity (Weingast, Shepsle, and Johnsen Reference Weingast, Shepsle and Johnsen1981). If the costs of a project are minimal, there is little reason for other legislators to oppose a particularistic bill. Larger projects may be supported as part of a logroll or reciprocal agreement, which may be more attractive to party leadership when divided government necessitates bipartisan support for a project. When collective and particularistic spending are equally valued by a legislature, spending on collective goods decreases as coalition formation becomes more difficult and more of the budget is used to buy support through particularistic projects (Volden and Wiseman Reference Volden and Wiseman2007). Majority party leaders have a greater incentive to consider particularistic policy introduced by minority party members when a small, district-specific reward can be used in exchange for the legislator’s vote on either some other district-specific project or on larger policy issues (Binder Reference Binder1996). There are incentives for bicameral support as well, as members of one chamber will support the projects introduced by legislators in the other chamber when there is overlap between their districts because they are able to take advantage of voter inattention to claim credit for delivering the project to their shared constituents (Chen Reference Chen2010).

Legislators are not the only elected representatives interested in delivering pork and pet projects to voters. Governors can be just as reelection minded as state representatives, particularly if they are in their first term or have aspirations for further political office. By supporting a district policy they are able to claim partial credit for the project or policy change with local constituents. When the individual district representative is a co-partisan, the governor has an additional incentive to support the member’s legislative agenda to improve the electoral fortunes of his co-partisans. Even when the governor is of the opposite party as the member who proposed the legislation, if the voter does not know who to attribute responsibility to, the governor may be able to claim some degree of credit just for signing the bill (Brown Reference Brown2010). The governor may also be able to use the promise of support for particularistic policies as an incentive to buy support among reluctant or ideologically distant legislators for his own agenda (Bullock and Hood Reference Bullock and Hood2005).

Whether it is part of a logroll, a reciprocal agreement, or an attempt to share credit, legislators and governors have several incentives to support projects backed by members of the opposite party. In terms of concessions that either the majority leader or governor can make to an individual legislator, supporting legislation to designate a road as a state aid highway or exempting a farm from agricultural nuisance regulations are considerably lower cost than bargaining on the particulars of larger policy issues. Yet it has the potential to provide considerable benefit to both the individual legislator and anyone else who is able to claim credit for the project if it is something that the constituents are calling for. As a result, when statewide policy change is difficult to achieve, particularistic policy is an attractive option for legislators looking for ways to demonstrate they are working for the voters who elected them.

Data and methods

Data for this project consist of 165,000 bills introduced in state legislatures in thirteen different states at different intervals from 1880 to 1997, collected by Gamm and Kousser (Reference Gamm and Kousser2010) in an exhaustive review of state legislative journals. The states are Alabama, California, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New York, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington, selected to maximize variation across a number of state and legislative characteristics such as legislative professionalism, population demographics, region, and the structure and rules of the legislature. The years studied are the regular sessions of 1881, 1901, 1921, 1941, 1961, 1981, and 1997 to provide historical variation (Gamm and Kousser Reference Gamm and Kousser2010).Footnote 3 The unit of analysis is the state legislative session in a given state and year. Because my focus is on partisan control of the state legislature and governor’s office, the five non-partisan legislatures are excluded from the analysis.Footnote 4

Using the legislative journals of each state, all of the bills introduced in the lower House for each legislative session were identified and each bill was classified as “statewide,” “general local government” or “district” based on the intended target of the legislation. District bills are those that refer to a “specific, geographically distinct area of the state,” (Gamm and Kousser Reference Gamm and Kousser2010, p. 8) such as HF 1739 from the 1997 session of the Minnesota state legislature, which authorized the city of Foley to use economic development funds to construct a wastewater treatment plant. Other examples include Mass H. 1059 in the 1961 session in Massachusetts, which established a trailside museum in the Jamaica Plain district of Boston, and HB 5255 in the 1997 session in Michigan, which proposed a $3 million grant for Detroit public schools to hire security officers. Although some district-specific bills are commemorative or administrative in nature, many represent investments in local communities.

Statewide bills are those that apply to the entire state, whole populations or industries, or state government operations, such as Wash H. 435 from the 1941 session of the Washington state legislature, “an act defining and regulating the business of making loans in the amount of $300 or less. This category also includes bills such as HB 147 from the 1997 session of the Virginia General Assembly, which increased the penalties for driving under the influence, and AB 1373 in the 1981 California General Assembly, which increased the allowed family contribution for college students who apply for financial aid as independents.

The remaining bills, which are classified as “general local government,” deal with local government issues, but are not targeted at specific cities or jurisdictions and instead apply broadly to multiple cities, counties, or other units of government across the state. Some are highly targeted, such as Ala. H. 902 from the 1939 Alabama state legislature, which was “to amend an act permitting the playing of tennis, golf, baseball, and operating of picture shows on Sunday in cities of a population not less than 15,000 or more than 40,000.” Others are more broadly applicable, such as HB 431 in the 1997 Texas state legislature, which proposed a cap on how much school districts could pay their administrators.

The dependent variables for the analysis are first, the number of bills introduced in a state legislative session, and second, the proportion of bills introduced that fall into each of the three categories. The number of bills introduced in a given session ranges from 136 in the 1881 session of the Montana Territorial Legislative Assembly to 10,324 in the 1981 session of the New York State Assembly, with an average of 1,816 bills across all sessions. Figure 1 shows the average number of bills introduced by both state and year. As one would expect, there is a steadily increasing trend in the number of bills introduced when considered by year, whereas the number of bills introduced by state varies considerably both within and across states. Populous states such as California, Massachusetts, and New York have a high variance, whereas there is significantly less variation in Montana and Vermont.

Figure 1. Number of bills introduced by state and year.

Looking at the types of bills introduced in each session, statewide bills dominate, with an average of 67.5% of each observed legislative session’s bills devoted to statewide policy issues. General local government bills represent an average of 15.94% of bills introduced, and district-specific legislation comprises the remaining 16.63%. However, a closer look at the data reveals significant variation in bill composition across the state legislative sessions. Statewide bills range from 30.6% of those introduced in Alabama in 1900 to 89.5% of bills in California in 1981. Conversely, the 1900 Alabama state legislature saw the highest rate of district bills introduced at 68%, whereas only 0.5% of the bills introduced in the 1997 Montana state legislature were focused on particularistic policy. For general government bills, the range is from 1% in the 1901 Virginia state legislature to 32.6% in the 1881 Illinois state legislature. Figure 2 shows the average percentage of each bill type introduced by both state and year.

Figure 2. Percentage of bill type by state and year.

The key explanatory variable of interest in my analysis is whether the legislature and governor’s office are controlled by the same party in a given state and year. The Divided Government variable is coded “0” for unified government when the state House, Senate, and governor’s office are all controlled by the same party, and “1” for divided government otherwise.Footnote 5 Gamm and Kousser’s dataset provides the partisan composition of the lower house for each legislative session. For the upper chamber and the governor’s office, I identified partisan control using both state legislature websites and data on state election results for 1938–2000 drawn from the Book of the States. I supplemented and cross-checked these data with a dataset of partisan division of state governments from 1834 through 1985 (Burnham Reference Burnham1985). These data provide the partisan control of the state House, Senate, and governor for every legislative session from 1834 to 1985 as well as the partisan composition of both legislative chambers. In instances where I was unable to determine which party held control of the state Senate, I relied on the party affiliation of the Senate’s elected majority leader or equivalent as a proxy.Footnote 6

Of the 86 observations included in this analysis, 55 of them were from legislative sessions where both the legislature and the governor shared partisan control and the remaining 31 represent divided government. Looking more closely at those 31 instances of divided government, they are drawn from eleven different states at six different periods of time. Vermont is the only state that did not see divided government for any of the observed legislative sessions and 1921 is the only year that did not see divided government in any of the states. The spread of divided government across the states is relatively balanced, ranging from one instance in Alabama to four in Michigan and Montana. The year observations are less balanced, with a trend toward increasing instances of divided government in later years. Where there were only two instances observed in 1881, in 1997 eleven of the thirteen states in the study had split party control of state government. Figure 3 provides a visualization of divided government by state and year.

Figure 3. Instances of divided government by state and year.

I also include a measure of how long the government has been divided, as I expect changes in bill composition will be greatest immediately following the shift from unified to divided government. Legislators change their behavior in response to a change in the political conditions, but if it persists for some time, legislators adapt to divided government as the “new normal.” Years Divided provides the number of years that the government has been split, ranging from zero in cases of unified government, to 23 years for the 1997 New York legislature. As the number of years of divided government increases, the shift from statewide to district-specific bills should dissipate, with fewer district bills introduced each year.

In addition to the divided government variables, I include several controls shown to affect the composition of bills introduced by Gamm and Kousser (Reference Gamm and Kousser2010).Footnote 7 They test a party competition theory originally advanced by V.O. Key that when a legislature is dominated by a single party, members are prone towards factionalism and “an obsession with particularistic bills” (Key Reference Key1949, p. 5). They find that increased party competition within the state House is associated with an increase of statewide policy bills, whereas legislatures dominated by a single party see more district-specific legislation introduced. Therefore, I include Majority Party Margin to represent the degree of party competition in the state House. This is the difference between the percentage of total seats in the lower house held by the majority party and those held by the minority party as reported by Gamm and Kousser (Reference Gamm and Kousser2010). This may seem counterintuitive to my theory of divided government, but I argue that the two variables represent different dynamics in the state. The majority party margin variable accounts for the effects of partisan composition within the state House, whereas the divided government variable accounts for the partisan composition of the state government as a whole. Although they are negatively correlated, there is still substantial variation in the majority party margin variable under both divided and unified government. On one hand, there are cases such as Texas in 1981 where the Democratic party held a commanding lead in the lower house, with 114 seats to the 34 seats held by Republicans, but the Governor’s mansion was held by Republican Bill Clements. In cases such as this, the tendency towards particularistic bills within the House is amplified by a governor from the opposing party who is likely to oppose the preferred policy initiatives of the legislative majority. On the other hand, Illinois in 1941 provides an example of the opposite dynamic in which the Republican party swept nearly all statewide races but had only a five seat margin in the state House. Given their tenuous hold on power, majority party legislators should be motivated to take advantage of the opportunity to pursue their preferred policies while the window is open.

Legislative professionalism is also likely to affect the composition of bills introduced in state legislatures. Statewide policy is typically more complicated to draft than most district-specific legislation and is therefore more likely to come out of a more professional legislature where the necessary resources and time are available (Kousser Reference Kousser2005). The Squire Index is a widely used measure of legislative professionalism in state legislatures that is based on the salary and benefits legislators receive, the time demands of legislative service, and the resources available in the legislature. Unfortunately, it is not available for state legislative sessions before 1979 and it is not reasonable to assume that the professionalization of a legislature in 1979 can be used to represent professionalization in 1921 (Squire Reference Squire2007). In the absence of a comprehensive measure, I use Turnover and Legislator Salary as proxies for state legislative professionalism. Turnover is measured as the percentage of legislators currently serving their first term in the state House, as in Burns et al. (Reference Burns, Evans, Gamm and McConnaughy2008). As legislators return to the state capitol for repeated sessions, they develop knowledge of specific policy issues and the legislative process. They also build connections within the legislature that help them advance statewide policy changes, and are more likely to consider further political ambitions. This should translate to an increased focus on statewide bills as legislators develop the expertise and motivation to tackle complex policy issues.

Legislator Salary is measured as the ratio of legislator salary (plus per diem) to state per capita income as in Burns et al. (Reference Burns, Evans, Gamm and McConnaughy2008) and Gamm and Kousser (Reference Gamm and Kousser2010). Measuring salary in relation to state per capita income provides an indication of how attractive a legislative seat is compared to other professional opportunities in the state and allows for comparability across state and time. As a measure of legislative professionalism, the expectation is that increased legislator salary reflects a more professional legislature and will therefore be associated with greater attention to statewide policy initiatives. Notably, Gamm and Kousser (Reference Gamm and Kousser2010) find the opposite, which they attribute to an electoral connection. When the jobs in the state legislature pay well, legislators are motivated to keep those jobs and pursue district-specific legislation to bolster their reelection chances.

I also include controls for the type of district that a legislator is representing as this should also affect the composition of legislation introduced. Size of Biggest City is the percentage of the state’s total population who live in the largest city at the time of each legislative session. I include this as I expect states dominated by a large metropolis are likely to see more district-specific legislation introduced as members representing the large city can introduce a city-specific bill that benefits all or most of their district. Finally, Income per Capita is measured in constant 1982–1984 dollars by the thousand and is included to account for the likelihood that voters in wealthier states are more likely to ask for state-level policy changes. Summary statistics for all variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary statistics

This is by no means a complete list of all possible determinants of the type of legislation introduced. Institutional rules vary by state, including different veto override thresholds and different procedures for introducing legislation. For example, I expect divided government would have less of an impact in states like Alabama where only 50% of the legislature is needed to override a veto, compared to the more common 2/3 threshold. In states where the governor has significant policymaking power through budgetary control, proposal power, or other institutional mechanisms, divided government is likely to have a greater impact as state legislators from the other party expect their chances of enacting statewide policy changes are bleak. However, these powers are generally fixed within a given state over time and therefore I do not have sufficient variation to model their impact on bill composition. Instead, I include state and year fixed effects in all models to account for state- and time-invariant factors.Footnote 8

Similarly, I expect electoral rules and procedures also influence bill introductions as legislators pursue particularistic policy to improve their chances at reelection (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974). Bagashka and Clark (Reference Bagashka and Clark2016) find that term-limited and retiring members introduce less particularistic legislation and members running in open primaries introduce more district-specific bills. In the aggregate, electoral considerations are likely to result in a higher proportion of particularistic bills introduced in states with more competitive or inclusive electoral systems. Political climates vary by state, with some states more prone to partisan shifts than others. Conditions vary by year as well, as state governments contend with national factors, from economic trends to federal policymaking. I expect the greatest impact of electoral considerations can be found at the individual level, as Bagashka and Clark (Reference Bagashka and Clark2016) find, but electoral rules and conditions particular to a given state or year are also accounted for with the model fixed effects.

Analysis

My theory predicts that under divided government, the total number of bills introduced remains constant while the composition of legislation shifts so there are fewer statewide bills and more district-specific bills introduced. To test the first hypothesis, I estimate a two-way linear fixed-effects model with the logged number of bills introduced in a session as the dependent variable.Footnote 9 State and time fixed effects account for unobserved heterogeneity that affects both the likelihood of divided government and the composition of bills introduced in a given state legislative session. The results in Table 2 show no evidence of a relationship between divided government and the number of bills introduced in a legislative session. Under divided government, legislators continue to introduce legislation at the same rate as under unified government, supporting the argument that legislators maintain a certain level of legislative productivity even if divided government makes it more difficult to pass certain bills. Knowing that the Senate or executive is controlled by the opposing party does not lead members to stop introducing legislation.

Table 2. Divided government and bill introductions

Note: Clustered (state) standard-errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.001

** p < 0.01

* p < 0.05

† p < 0.1

Although divided government does not affect the quantity of work done by legislators, the primary question of this study is whether it changes the substance of what they work on. This second hypothesis is tested with a series of weighted fixed-effects models for each of the three dependent variables of interest: the percentage of bills introduced that are focused on statewide, district, and general local government issues. The models are weighted by the number of bills introduced in each state legislative session because the proportion of each bill type is likely to be more accurately measured in states with more bills to draw from. A single misclassified bill will have a much greater impact on the bill type proportions if it is one of the 136 bills from the 1881 session of the Montana Territorial Legislature than if it is one of the 10,324 bills from the 1981 session of the New York Assembly.Footnote 10 As in the bill introduction model, state and year fixed effects are included to account for unobserved factors particular to a given state or year.

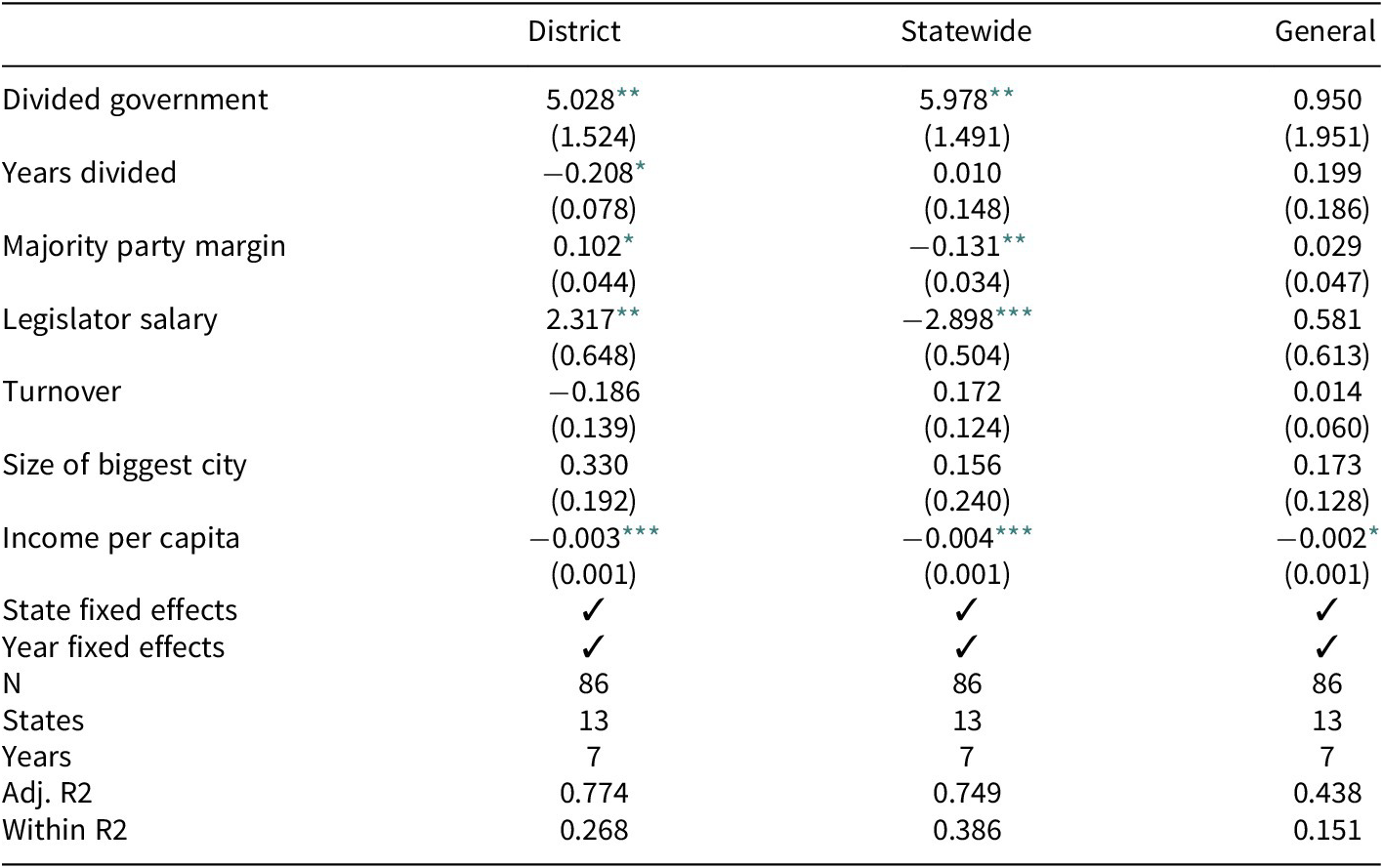

As Table 3 shows, Divided Government is both significant and substantively large in its relationship with both district and statewide bills. When the state House is not controlled by the same party as either the state Senate or the governor’s office, legislators introduce more particularistic district-specific legislation and make fewer attempts at statewide policy change. Ceteris paribus the percentage of district-specific legislation introduced is 5.03 percentage points higher under divided government than with unified government. Looking at statewide policy bills, the percentage introduced is 5.98 points lower under divided government. The percentage of general government bills introduced does not change, which I attribute to the in-between nature of this category in which they are not as targeted as district-specific bills, nor as broad as statewide policy initiatives. Although legislators continue to introduce legislation at the same rate under divided government as shown in Table 2, the results in Table 3 show there is a meaningful shift in the composition of bills they introduce.

Table 3. Divided government and bill composition as proportion

Note: Clustered (state) standard-errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.001

** p < 0.01

* p < 0.05

† p < 0.1

This shift is further illustrated in Figure 4, which displays the predicted percentage of district-specific, statewide, and general government bills under both unified and divided governments. The predicted outcomes are generated using all state-year observations and their counterfactuals in terms of divided government. Each observation is therefore in the prediction set twice: once with unified government and once with divided government. The shift in bill composition is apparent, with the median state legislature shifting from 14.2% district-specific and 69.4% statewide bills introduced under unified government, to 19.2% district-specific and 63.4% statewide bills introduced under divided government.

Figure 4. Predicted percentage of bills introduced by type for observed and counterfactual data.

To demonstrate what this looks like in practice, consider the 62nd General Assembly in Illinois which met in 1941 and 1942. Legislators in the House introduced 1324 bills, of which 897 concerned statewide policy initiatives, 61 were district-specific bills, and the remaining 366 dealt with general government matters. With the 1940 election of Governor Dwight Green, the Republican party regained unified control of the state government for the first time for the first time since 1932. The models in Table 3 predict that if the Democratic party controlled either chamber of the General Assembly or the governor’s office, legislators would have introduced an additional 67 district-specific bills and 79 fewer statewide bills. In the 180th General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (1997–1998), House members introduced 6,179 bills, of which 5,024 were statewide, 693 were district-specific, and 462 were general government. Although the Democratic party held a supermajority in both chambers of the legislature, Republican Bill Weld was in his second term in the governor’s mansion. The model predicts that under unified government, legislators would have introduced an additional 370 statewide bills and 311 fewer district-specific bills. However, in this case we must consider not only the presence of divided government but also that the state was in its seventh year of split partisan control. Accounting for these seven years decreases the change in the number of district-specific bills to a 3.56 percentage point shift, or 220 fewer.

Results for the control variables are generally consistent with previous findings or show no relationship with bill composition.Footnote 11 The one notable exception is Legislator Salary, which operates in the opposite direction than expected for a measure of legislative professionalism. However, this finding is consistent with Gamm and Kousser (Reference Gamm and Kousser2010), suggesting that in this context, the variable functions as a measure of the appeal of a state legislative job. If we assume that well-compensated legislators are motivated to retain their positions, these results are also consistent with previous research showing that reelection-minded legislators are more likely to pursue particularistic policies (Bagashka and Clark Reference Bagashka and Clark2016).

Robustness

In the previous section, I measured divided government as any instance in which either the Senate or the governor’s office are controlled by a different party than the House. As both the Senate and the governor have the power to block House legislation that does not align with their preferences, divided government should push House legislators toward district bills regardless of which one is controlled by the opposing party. However, previous research has shown differing effects of divided government depending on whether the legislature itself is divided, with the lower and upper chambers controlled by opposite parties, or the division is between the legislature and the governor’s office. For example, Rogers (Reference Rogers2005) shows that divided legislatures produce significantly fewer statutes, whereas there is no apparent effect on legislative production when the legislature is united against the governor’s office. Bowling and Ferguson (Reference Bowling and Ferguson2001) find that fewer bills become law when the legislature is divided, but only on “high-conflict” policy issues such as crime and welfare. In contrast, when the governor’s office is controlled by the opposite party of the legislature, more bills become law on “low conflict” policy issues such as agriculture and health care.Footnote 12

Within the 31 instances of divided government in my data, there are 19 instances in which both chambers of the legislature are controlled by the same party, with the governor’s office in opposition. In four cases, the lower chamber and the governor’s office are controlled by the same party, with the upper chamber in opposition, and in seven cases the lower chamber is the odd one out.Footnote 13 The limited number of observations makes it difficult to examine whether different forms of divided government have varying impacts, but as a preliminary effort I reestimate the models from Table 3 with an alternate measure, Divided Branch, which reflects whether the House and the governor’s office are controlled by opposing parties, disregarding the Senate. The Years Divided variable is adjusted accordingly to reflect the same division. What is notable about these results, presented in Table 4 is that the impact of divided government is even larger when measured only as those instances where the House and governor are controlled by opposing parties. When the governor is of the opposite party as the House majority, the proportion of district bills introduced in the House increases by 6.19 percentage points and the proportion of statewide bills decreases by 6.15 percentage points. This suggests that an opposition Senate alone is not enough to influence the bills House members introduce, although there are too few observations to tease out whether these results are being driven by an opposition governor or the combined opposition of the governor and Senate.

Table 4. Alternate divided government measure

Note: Clustered (state) standard-errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.001

** p < 0.01

* p < 0.05

† p < 0.1

Next I consider an alternate measure of bill introductions. The dependent variables used in the main specification measure the proportion of each type of bill introduced as the proportions illustrate how legislators divide their finite time and resources. Although there is no cap on the number of bills that can be introduced in a legislative session, individual legislators must deal with both institutional and personal constraints. If a legislator chooses to devote significant time and effort to a complex state policy issue that they have strong preferences on, it leaves less time for district-specific issues. Similarly, the legislator who devotes all of their resources to introducing district bills for their constituents has less capacity to draft statewide legislation.

However, measuring bill composition as a proportion of all bills introduced means the results may be driven by a marked increase in the number of district bills introduced under divided government without a corresponding decrease in the number of statewide bills introduced. Although Table 2 showed that divided government does not have an effect on the total number of bills introduced, here I examine the relationship between divided government and the total number of district, statewide, and general local government bills introduced in each legislative session. Table 5 displays the result of three negative binomial models with unconditional state and year fixed effects.Footnote 14 The coefficients on Divided Government are significant and in the expected direction in both the district and statewide bill models. The shift in the proportion of district and statewide bills introduced under divided government is due to both an increase in district bills by a factor of 1.398 and a decrease in statewide bills by a factor of 0.914.

Table 5. Divided government and bill composition as count

Note: Clustered (state) standard-errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.001

** p < 0.01

* p < 0.05

† p < 0.1

To provide substantive context for the results, I estimate the predicted values for the number of district and statewide bills introduced in each state legislative session under both the observed condition and the counterfactual. The models predict that under unified government, an average of 277 district and 1,351 statewide bills will be introduced. The average predicted shift under divided government is an additional 111 district bills and 117 fewer statewide bills, for a total of 388 district and 1,234 statewide bills introduced. Combined with the previous findings, this provides further evidence that although divided government does not affect the number of bills introduced, it does result in a clear shift in the type of bills legislators choose to introduce.

I argue that this shift is the result of legislators turning to district-specific legislation when they expect that broad policy shifts will be more difficult to enact due to partisan conflict. Given that particularistic policy is less likely to involve partisan conflict, this is consistent with Bowling and Ferguson’s (Reference Bowling and Ferguson2001) finding that more legislation on low-conflict issues passes under divided than unified government. The shift is also consistent with the tendency of governors to use particularistic policy to buy legislative support for their agenda and their ability to claim credit for these projects (Brown Reference Brown2010; Bullock and Hood Reference Bullock and Hood2005). However, it is unclear whether the expectation that district-specific legislation is easier to pass than statewide policy initiatives is borne out by reality.

An ideal test of the success of different types of legislation would compare the passage rates of all district and statewide bills under both divided and unified government. Collecting and coding the necessary data for such an analysis is beyond the scope of this project, but as a preliminary examination, I look at bill passage rates for a sample of 3,739 bills compiled and provided by Gamm and Kousser (Reference Gamm and Kousser2013). The sample includes between 25 and 78 bills for each state-year combination, all introduced in the lower chamber and split between bills classified as district and general local government. Across all 2,014 district-specific bills in the sample, there is no relationship between divided government and the likelihood a bill becomes law. However, my expectation is not that district-specific legislation is more likely to be enacted under divided than unified government, but that under divided government, district-specific legislation has a comparative advantage over broader policy initiatives when it reaches the governor’s desk.

The models in Table 6 show the relationship between bill composition and enactment under both unified and divided government, with two caveats.Footnote 15 First, the observations are limited to the subsample of 1,746 bills that passed in their respective state houses. Second, the District Bill variable is a binary indicator of whether a bill is classified as district or general local government, as there are no statewide bills in the sample. Still, the results suggest that under divided government, district bills introduced in the lower chamber may be advantaged over general local government bills once they move beyond the house.Footnote 16 Although this does not necessarily mean that district bills are advantaged over statewide legislation, the previous results suggest that general local government bills function as a neutral baseline.Footnote 17 Under divided government, the odds of a bill being enacted are 1.52 times greater if it is district-specific rather than general local government. Although this is by no means conclusive evidence, it at least suggests that legislators who introduce more district-specific bills under divided government are not behaving irrationally.

Table 6. Likelihood of bill enactment

Note: Clustered (state) standard-errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.001

** p < 0.01

* p < 0.05

† p < 0.01

Discussion and conclusion

The results presented here provide strong evidence that although the quantity of legislation remains the same, legislators introduce more district and fewer statewide bills when partisan control of the state government is split. As Mayhew (Reference Mayhew1991) argues, the business of governing does not stop simply because there is divided control of the state government. The legislators who wish to remain in office still need to provide their constituents with a reason to reelect them and so they still introduce policy proposals at the same rate, resulting in a pattern that is similar to what Mayhew finds in his study of legislative enactments in the US Congress. Although he looks at bill passage, and I examine bill introductions, there is an overall tendency towards constancy for both. Although the rate of bill introductions in state legislatures has steadily increased over time, this trend is unrelated to partisan control of the government.

However, where I diverge with Mayhew is his assertion that divided government has only minimal effects. Looking beyond legislative enactments and the rate of bill introductions, I find that divided government changes the focus of members in state legislatures, pushing them to focus more on particularistic bills that provide a direct benefit to their home district and less on statewide policy changes. As district-specific bills generally have less ideological content, it is reasonable for legislators to expect they will be generally easier to pass than statewide policy when the government is divided. By shifting to particularistic policy, they are introducing bills that benefit their constituents and can help their reelection campaign. Furthermore, they expect their efforts will be more likely to succeed because the policy is unlikely to affect other legislative districts and the governor may derive some benefit from the initiative, either by supporting a co-partisan, through their own credit claiming, or as an exchange for the legislator’s support on other issues. From the legislator’s perspective, a shift of focus to district-specific legislation under divided government is likely a more beneficial use of their time than advocating state policy changes that do not have the necessary support to pass.

Legislators introduce bills that reflect their policy positions and for which they expect to derive some benefit, whether that is the ability to take a position on an important issue or a desired policy change. That we observe a marked shift in the content of legislation introduced under divided government suggests a shift of the priorities and expectations of legislators. Future research should take a more fine-grained look at how the content of legislation shifts, to distinguish between different types of district and statewide bills. Does the increased attention to district bills reflect more commemorative bills, administrative issues, or resource transfers? Is the decrease of statewide bills driven by less attention to complex and high-conflict issues, or something else? More work should also be done to examine the relationship between bill content and legislative enactments, to build on the preliminary analysis in Table 6 and better understand whether the expectations of legislators are supported by reality.

Still, this study highlights the importance of looking beyond bill enactments to consider how changes in the political environment influence legislative behavior in the earliest stages of the legislative process. That legislators introduce more district and fewer statewide bills under divided government provides a strong indication that they believe they will gain a greater benefit from particularistic policy under divided government and that it is an effective way to break through the legislative gridlock.

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available on SPPQ Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.15139/S3/NVOYH5 (Craig Reference Craig2023).

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Thad Kousser and Gerald Gamm for generously sharing their state legislative bill data. The author also thanks Jesse Crosson, Vlad Kogan, Irfan Nooruddin, and Zac Peskowitz for helpful comments and feedback.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship [grant number DGE-1343012].

Competing interest

The author declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Biography

Alison W. Craig is an assistant professor of government at the University of Texas at Austin whose research focuses on American political institutions and political methodology.