Young people’s use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) to communicate and interact with other people has increased in recent decades (Duerksen & Woodin, Reference Duerksen and Woodin2019). Technologies have changed the ways in which young people relate to each other, including dating relationship dynamics. Burke et al. (Reference Burke, Wallen, Vail-Smith and Knox2011) found that young people use a large number of media and digital tools to develop and maintain dating relationships (e.g., text messages, emails, mobile phones, social networks, or webcams). It is undeniable that the use of ICTs can have important benefits on personal and social levels, as well as positive effects on adolescents’ socialization (Caridade et al., Reference Caridade, Braga and Borrajo2019), allowing them to explore and define their identity and personality, express themselves and build new relationships (Hinduja & Patchin, Reference Hinduja and Patchin2020). However, these tools may also provide new opportunities for some individuals to exert control over others, given that it is now easier than ever before to stalk someone, collect information on them as well as harass them in multiple contexts (Fernet et al., Reference Fernet, Lapierre, Hébert and Cousineau2019). Technology has modified the ways in which violence can be perpetrated and suffered, making it immediate, beyond any physical limit, through a wide number of media (e.g., email, instant messaging services and social networks) and with minimal effort, thereby causing a greater impact on the victim, more rapidly and in different areas of his/her life. In this way, along with these changes in relationships, a new form of intimate partner violence has also emerged, called cyber or digital dating violence or abuse (Zweig et al., Reference Zweig, Lachman, Yahner and Dank2014).

The range of terminology used in the scientific community is currently very wide and varied, probably since it is a relatively recent phenomenon. In the absence of a definitive term, this review proposes that the term to use in future studies should be cyber dating violence (CDV) because, on the one hand, the term cyber denotes a relationship with information technology (encompassing all kinds of technologies relates to the virtual world) and, on the other hand, the term dating violence refers to violence in relationships between adolescents or young people, where the members of the couple do not live together, are not financially independent from their parents, and do not have well-established relationships (Ibabe et al., Reference Ibabe, Arnoso and Elgorriaga2020). Cyber dating violence has been defined as a form of control and harassment by the dating partner or ex-partner using new technologies and the media (Zweig et al., Reference Zweig, Lachman, Yahner and Dank2014). It has also been observed that the definitions of CDV tend to include a list of possible behaviors and different technological media, which is not wholly adequate for clarifying the construct. Rodríguez-Domínguez et al. (Reference Rodríguez-Domínguez, Pérez-Moreno and Durán2020) pointed out methodological deficiencies in the construction of knowledge in the field of CDV, indicating for example, a lack of attention to manifestations of sexual aggression. Although it is not easy to establish a definitive classification of the different manifestations of CDV due to emerging new behaviors related to technology use, we propose five dimensions. Thus, cyber dating violence is understood in this paper as the perpetration of different types of aggression (psychological direct, control, public harassment, exclusion, and sexual) to the partner or ex-partner in the context of a dating or courtship relationship, via any digital media. Table 1 shows the definitions and examples of the five potential dimensions of the cyber dating violence construct.

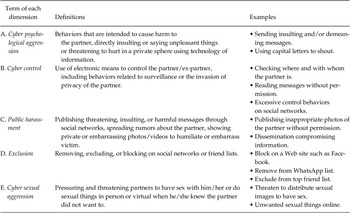

Table 1. Terms, Definitions and Examples of Behaviors of Each Dimension of Cyber Dating Violence

To advance research on CDV, it is important not only to have an appropriate conceptualization of CDV but also adequate instruments for its measurement (Cava & Buelga, Reference Cava and Buelga2018). Consequently, the objective of this research was to describe the assessment instruments most used in CDV among young couples and to identify the best based on the quality of evidence in their psychometric properties. To achieve this goal, a systematic review was carried out, ensuring transparent and complete reporting of the systematic search. This systematic review can be helpful in understanding the reasons for the differences found in results regarding CDV prevalence rates in all previous reviews (Brown & Hegarty, Reference Brown and Hegarty2018; Caridade et al., Reference Caridade, Braga and Borrajo2019; Cavalcanti & Coutinho, Reference Cavalcanti and Coutinho2019; Rodríguez-Domínguez et al., Reference Rodríguez-Domínguez, Pérez-Moreno and Durán2020) since it shows how all the instruments present different conditions in their methodological approaches, which can affect the interpretation of the evidence found in their research. The present review analyzed the quality of psychometric properties using the COSMIN checklist, which takes into account both the methodological quality and results of each psychometric property.

Method

Systematic Review

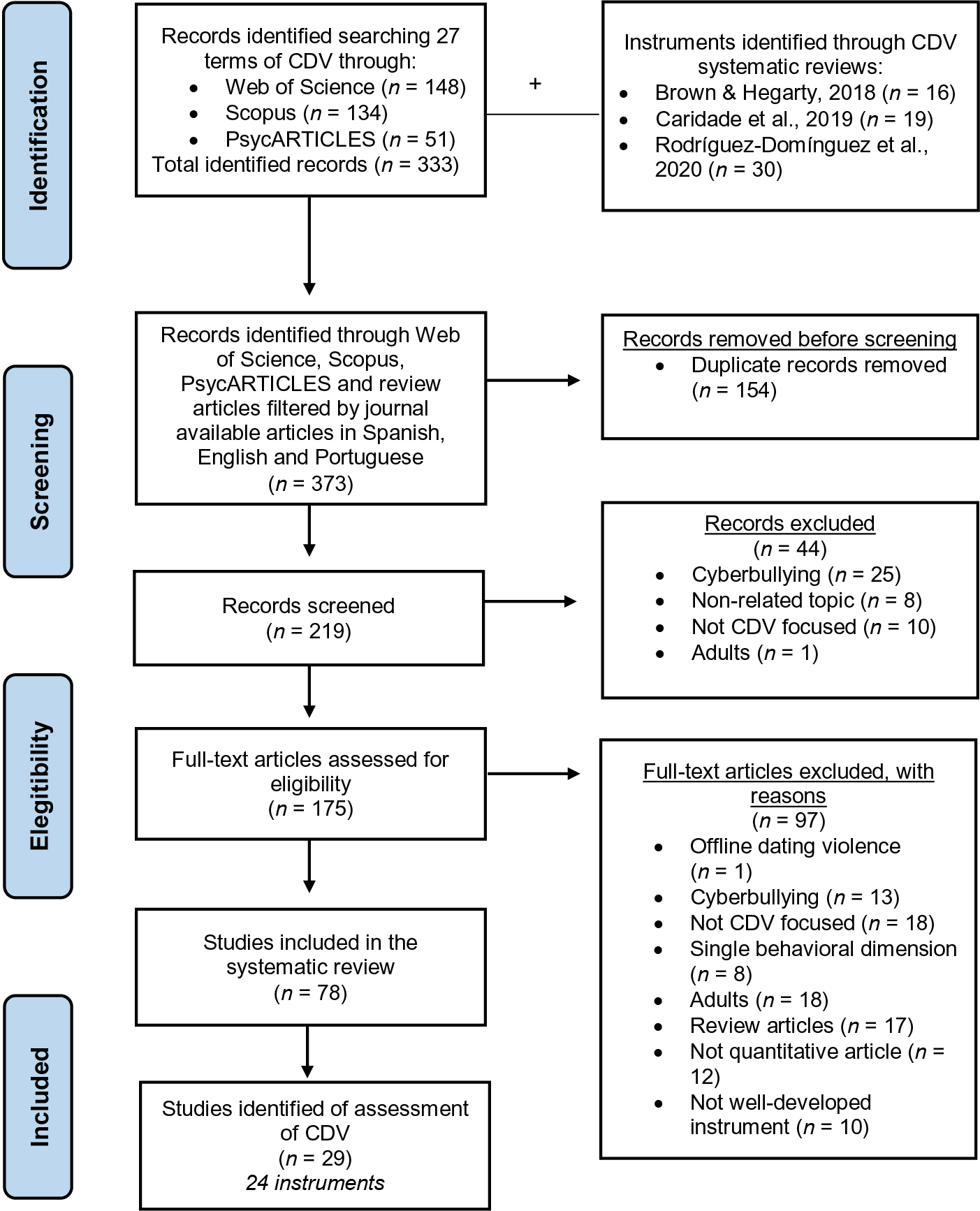

This systematic literature review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines with a 27-item checklist in order to ensure transparent reporting (Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald and Moher2021). The identification, screening, and eligibility of the studies included are outlined in the flow diagram (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the Review Process according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Search Strategies

The bibliographical searches were carried out in three electronic databases: Web of Science (title, abstract, author keyword and keyword plus), Scopus (title, abstract, author keyword), and PsycARTICLES (all text option). Journal articles published in English, Spanish or Portuguese up to July 2021 were selected. During the full-text assessment for eligibility, the reference lists of the selected articles were also reviewed to identify additional studies that were not identified during the bibliographical search. Retrieved articles from three databases were exported to RefWorks in order to make the removal of duplicates much easier. The selection process was carried out by reading abstracts, but sometimes articles were removed after reading the full text.

For the search, 27 terms of CDV were used (“electronic victimization” OR “cyber dating abuse” OR “cyber dating aggression” OR “cyber dating victimization” OR “cyber intimate partner violence” OR “ciberviolencia de pareja” OR “cyber dating violence” OR “ciberviolencia en el noviazgo” OR “digital dating abuse” OR “digital dating violence” OR “digital dating victimization” OR “digital dating aggression” OR “intimate partner violence through electronic mediums” OR “violencia de pareja a través de medios electrónicos” OR “computer mediated communication based teen dating violence” OR “cyber psychological abuse in romantic relationships” OR “intimate partner cyber aggression victimization” OR “virtual intimate partner violence” OR “violencia de pareja online en la adolescencia” OR “violencia de pareja virtual” OR “electronic aggression in emerging adult romantic relationships” OR “electronic intrusion cyber dating aggression” OR “ciberagresión en el noviazgo” OR “electronic dating aggression” OR “technology assisted adolescent violence” OR “technological intimate partner violence” OR “partner directed cyber aggression”).

Eligibility Criteria

For this review, the following inclusion criteria were applied: (a) Publications that adopt constructs strictly related to the phenomenon of cyber dating violence (e.g., dating partners); (b) studies on the adolescent and/or young population (with a maximum mean age of 28–30 years or slightly higher); (c) publications in English, Spanish and Portuguese. The first criterion is related to the fact that some studies analyze this phenomenon through constructs in nonintimate relationships such as cyberbullying (e.g., cyber aggression, cyber violence).

The exclusion criteria applied were: (a) Studies analyzing cyber abuse in nonintimate relationships (e.g., between peers); (b) theoretical articles or qualitative studies; (c) studies not including cyber dating violence measures; (d) studies on a mostly adult population; and (e) studies focused on single behavior of cyber dating violence (e.g., electronic intrusion, sexting coercion). This last criterion is related to the fact that some publications only analyze single behavioral dimensions. Since cyber dating violence is conceptualized as multidimensional, only studies that explored this phenomenon’s multidimensionality were included. Figure 1 shows the literature search flowchart and the selection of articles from the analyzed sources, with a total of 78 scientific articles addressing CDV obtained. Table 2 lists all psychometric studies using the instruments. Moreover, the remaining studies (which used CDV instruments but were not psychometric studies) are presented in Appendix A. All studies have the corresponding reference list, but the psychometric studies analyzed in the paper have an asterisk in the References section.

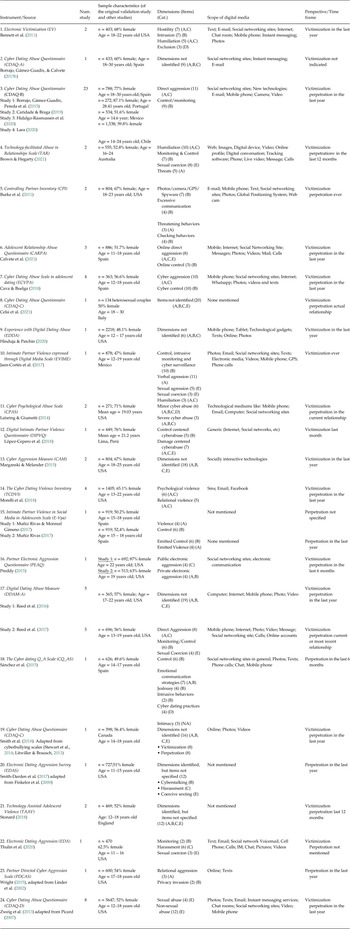

Table 2. Sample Characteristics, Dimensions, Digital Media, Perspective and Time Frame of the Selected Instruments

Note. Cat. = Categorization (A = Cyber psychological aggression; B = Cyber control; C = Public harassment; D = Exclusion; E = Cyber sexual aggression); NA = non-applied.

Analysis of the Psychometric Evidence of the Instruments

Some of the standards developed in the COSMIN Guide (COnsensus based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments) were used to evaluate the psychometric properties of the analyzed instruments (Mokkink et al., Reference Mokkink, Prinsen, Patrick, Alonso, Bouter, de Vet and Terwee2018) following three steps:

First step: Assessment of the methodological quality of the studies. The COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist is applied. The term “risk of bias” refers to whether the results, based on the methodological quality of each study, are trustworthy. This checklist contains different standards referring to design requirements of studies on measurement properties. For each measurement property a COSMIN box is developed, containing different items, named standards, which are needed to assess the quality of a study on that specific measurement property. For example, Standard 1 on Structural Validity indicates that to determine the structure of the instrument a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (Rating: Very good) is preferred over Explorative Factor Analysis (Rating: Adequate). COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist contains ten boxes with standards for: (a) Instrument development (35 items), (b) content validity (31 items), (c) structural validity (4 items), (d) internal consistency (5 items), (e) cross-cultural validity (4 items), (f) reliability (8 items), (g) measurement error (6 items), (h) criterion validity (3 items), (i) hypothesis testing for construct validity (7 items), and (j) responsiveness (13 items). The evaluation of these properties was achieved by rating 116 items on a four-point scale (very good, adequate, doubtful, inadequate quality, or not applicable). An overall rating for methodological quality was provided for each reported psychometric property by taking the lowest rating of any standard in the box (i.e., “the worst score counts” principle).

Second step: Assessment of the reported psychometric properties quality. The results of eight psychometric properties (content validity, structural validity, internal consistency, cross-cultural validity, reliability, criterion validity, hypothesis testing, and responsiveness) should be based on the results of all available studies per measurement property in order to determine whether each measurement property of the instrument is sufficient (+) within the pre-established quality criteria, insufficient (–) outside the pre-established quality criteria, inconsistent (±), or indeterminate (?) or less rigorous evidence or procedures that did not meet the pre-established quality criteria (Terwee et al., Reference Terwee, Bot, de Boer, van der Windt, Knol, Dekker, Bouter and de Vet2007). Additional details on these criteria can be found in the COSMIN manual for systematic reviews of instruments (Mokkink et al., Reference Mokkink, Prinsen, Patrick, Alonso, Bouter, de Vet and Terwee2018) (See Appendix B).

Third step: Best evidence synthesis: the GRADE approach. The quality of the overall evidence of each category was rated on a four-point scale (high, moderate, low, or very low), and instruments were categorized on the overall quality of evidence and results: Category A (instruments in this category will be recommended for use because results obtained with this instrument can be trusted), Category B (instruments may be used with caution, but require further research) and Category C (use of the measures in this category is not recommended). In cases classified as indeterminate or inconsistent it was not possible to assess quality with the GRADE approach. The recommended instruments which are useful and valid for measuring the same construct are those with higher COSMIN scores.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the selected instruments and psychometric studies in this systematic review. The results of each study and instrument with respect to methodological quality and reported psychometric properties quality rating are shown in Table 3. A trained researcher analyzed the methodological quality and psychometric properties quality of 29 studies. However, the best evidence synthesis was done by consensus between two trained researchers, specifically, the overall assessment of each instrument (total sufficient rating, quality of evidence and category).

Results

The search strategy resulted in 333 articles retrieved from three different databases and other systematic reviews. From this, 154 duplicates were found, resulting in 219 articles as shown in Figure 1. After assessing articles for inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 24 instruments and 29 psychometric studies were included in the methodological evaluation using the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist.

General Characteristics of the Selected Instruments

In Table, 2 characteristics of the psychometric studies corresponding to 24 instruments are shown. Most of the studies were conducted in the USA (n = 12), followed by Spain (n = 7), while the remaining studies were distributed in different countries (Mexico, England, Australia, Canada, Chile or Portugal). Important differences among the instruments in the evaluated aspects (types of digital media, perspective –perpetration vs. victimization, and time frame) were found. Moreover, the dimensions of CDV analyzed in these studies were very varied. In some studies, the CDV construct was underrepresented by focusing on measuring specific types of cyber dating violence (Rodríguez-Domínguez et al., Reference Rodríguez-Domínguez, Pérez-Moreno and Durán2020). Control behaviors, cyber psychological abuse and harassment were most commonly studied. It seems that there was no consensus regarding the construct of CDV, and the variations in dimensions across instruments hinder cross-study comparison. According to the categorization defended in the present study, the dimensions less taken into account in the analyzed studies were exclusion and sexual aggression.

Synthesized Evidence

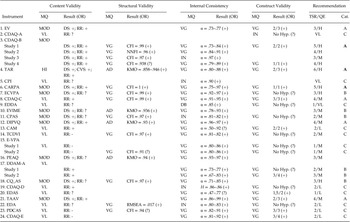

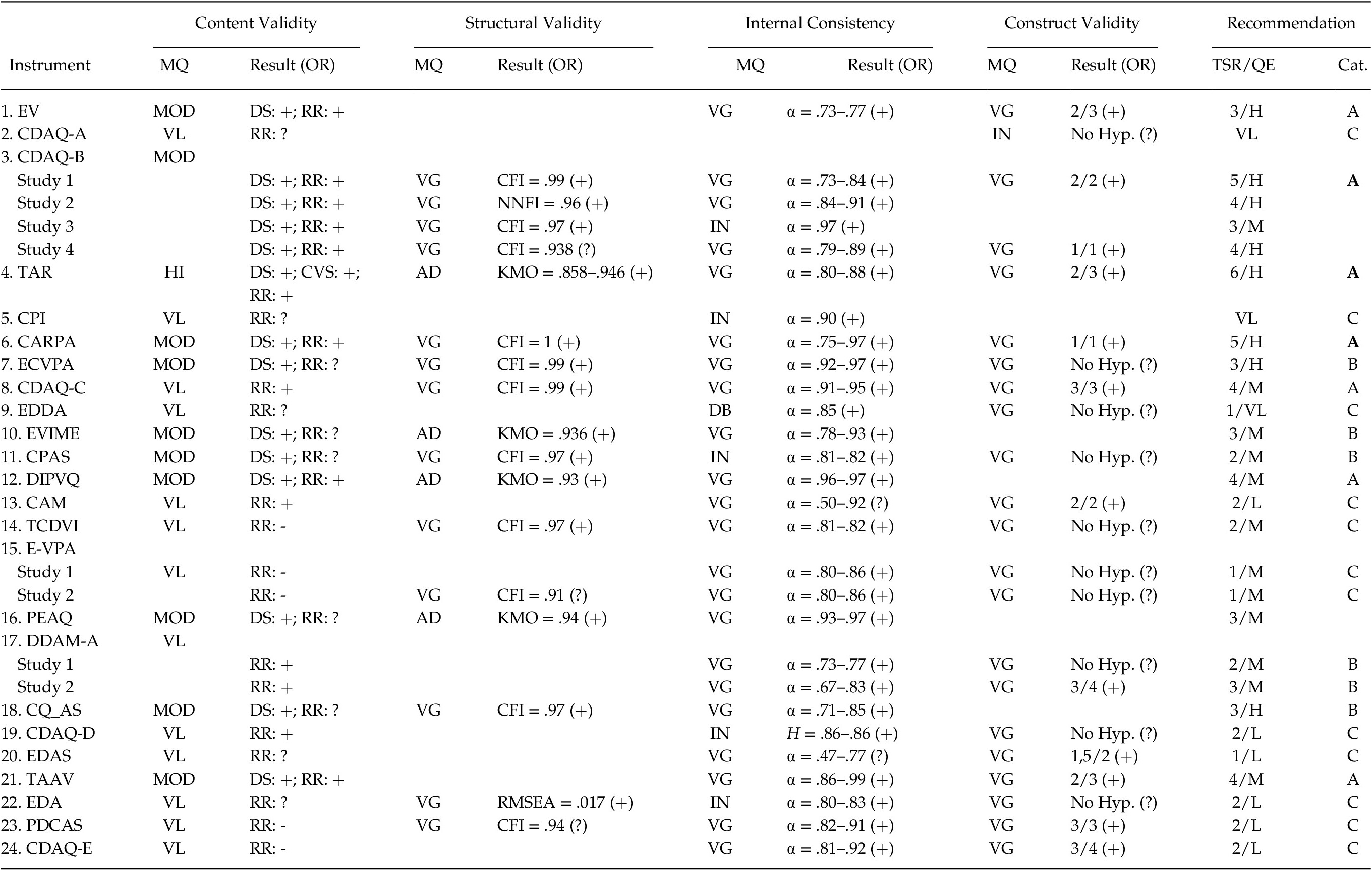

The overall ratings of the evidence for each measurement property of each instrument and their risk of bias ratings are reported in Table 3. No studies assessed or showed evidence of cross-cultural validity, test-retest reliability, criterion validity or responsiveness, so these properties are not discussed nor included in the table.

Table 3. Summary of the Quality Assessment of the CDV Measurement Instruments based on the COSMIN Guide

Note. COSMIN Risk of Bias Checklist rating. MQ = Methodological quality (VG = Very Good; HI = High; AD = Adequate; MOD = Moderate; DB = Doubtful; IN = Inadequate; VL = Very Low); OR = overall rating; blank cells indicate no results. Result of measurement property = + = Sufficient; +/− = Inconsistent; − = Insufficient; ? = Indeterminate. DS = Development Study; RR = Reviewers Rating; CVS = Content Validity Study; No Hyp. = No Hypothesis; TSR = Total sufficient rating; QE: Quality of evidence; Cat. = Categories for recommendations on suitable instruments (A = best suitable; A = recommended; B = with caution; C = not recommended).

Content Validity

Content validity is considered to be the most important measurement property of an instrument; this refers to the relevance, comprehensiveness, and comprehensibility of the instrument, that is, the degree to which the content is an adequate reflection of the construct to be measured (Terwee et al., Reference Terwee, Prinsen, Chiarotto, Westerman, Patrick, Alonso, Bouter, de Vet and Mokkink2018). Just one of the 29 studies performed a content validity study besides the development study and was thus the only one to receive a “high” rating on this property. Thirteen instruments did not even have development studies, having only the reviewer rating, thus receiving a “very low” rating. The remaining studies obtained a “moderate” rating, as they had performed a development study for the instrument. Knowing that content validity is the most important measurement property and one which can affect all others, the number of studies with very low ratings in this property is surprisingly high.

Structural Validity

Structural validity is a relevant measure when the instrument is based on a reflective model, in which all items are a manifestation of the same underlying construct (Mokkink et al., Reference Mokkink, Prinsen, Patrick, Alonso, Bouter, de Vet and Terwee2018). Seventeen of the twenty-nine studies examined the structural validity of the analyzed instruments. Thirteen studies conducted a confirmatory factor analysis and so received a “very good” rating for their methodological quality, while four performed just an exploratory factor analysis, thus being considered “adequate”. The remaining studies did not provide any information regarding this property.

Internal Consistency

Internal consistency measures the degree of the interrelatedness among the items, that is, the extent to which the items in a subscale are measuring the same concept. This property is relevant for questionnaires measuring a single construct by using multiple items (Terwee et al., Reference Terwee, Bot, de Boer, van der Windt, Knol, Dekker, Bouter and de Vet2007). Twenty-eight studies assessed the internal consistency of the instruments, of which five were considered “inadequate”. These ratings were due to the internal consistency statistics being calculated for the entire scale, not each subscale separately. One was “doubtful” due to lack of evidence that the scale was unidimensional, leading to uncertainty regarding whether internal consistency should apply (Mokkink et al., Reference Mokkink, Prinsen, Patrick, Alonso, Bouter, de Vet and Terwee2018). The remaining 22 studies that assessed internal consistency received a “very good” rating as it was calculated for each subscale and adhered to the other requisites for assessing this property.

Hypotheses Testing for Construct Validity

This property refers to the degree to which the results of an instrument are consistent with the hypotheses, assuming that it validly measures the construct to be measured (Mokkink et al., Reference Mokkink, Prinsen, Patrick, Alonso, Bouter, de Vet and Terwee2018). Many types of hypotheses can be tested but, in general, they concern comparisons with other outcome measurement instruments. In fact, every study that gave information about this property made comparisons with other outcome measures. However, ten of the studies that made these comparisons did not formulate specific hypotheses, leading to indeterminate results for this property.

Best Instruments for Assessing CDV

The current systematic review has detected the following three instruments as the most suitable for the assessment of CDV for adolescents and young people in the population of interest, based on their psychometric properties:

Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire (CDAQ-B; Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda, et al., Reference Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda and Calvete2015). Four psychometric studies were identified (Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda, et al., Reference Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda and Calvete2015; Caridade & Braga, Reference Caridade and Braga2019; Hidalgo-Rasmussen et al., Reference Hidalgo-Rasmussen, Javier-Juárez, Zurita-Aguilar, Yáñez-Peñuñuri, Franco-Paredes and Chávez-Flores2020; Lara, Reference Lara2020) reporting on the psychometric properties of the CDAQ-B (Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda, et al., Reference Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda and Calvete2015) based on adolescents and young adults. This instrument was adapted to four cultural contexts (Spain, Portugal, Chile and Mexico). The adaption studies of this instrument (Caridade & Braga, Reference Caridade and Braga2019; Hidalgo-Rassmusen et al., Reference Hidalgo-Rasmussen, Javier-Juárez, Zurita-Aguilar, Yáñez-Peñuñuri, Franco-Paredes and Chávez-Flores2020; Lara, Reference Lara2020) were carried out appropriately by consulting with experts, focus groups or involving the target population. These studies modified some of the items due to wording and context, and two of them used the instrument with a sample of adolescents (13–24 years), despite the original (Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda, et al., Reference Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda and Calvete2015) having been used in a sample of young adults (18–30 years). The three adaption studies showed positive and good-quality evidence in their psychometric properties, which means that this instrument is suitable for other contexts, with few changes. Moreover, this instrument has been more widely applied (23 studies) in comparison with other instruments (varying from 1 to 8 studies). The original study showed positive evidence in four indicators (content validity, structural validity, internal consistency, and construct validity). There was moderate-quality evidence supporting content validity. This instrument included 20 items related to three dimensions of CDV (Cyber psychological aggression, Cyber control, and Public harassment), but Cyber sexual and Exclusion were not included. This instrument could be highly recommended for assessing CDV in young people, but its application in adolescents under 14 years of age may be doubtful because the four psychometric studies did not cover the age range of adolescence, for which more validation studies are needed.

Technology-facilitated Abuse in Relationships Scale (TAR; Brown & Hegarty, Reference Brown and Hegarty2021). A psychometric study of TAR (Brown & Hegarty, Reference Brown and Hegarty2021) was carried out with 30 items in a population of 16–24 year-olds. High-quality evidence supporting content validity was found, and one content validity study was also rated as sufficient. The quality of the evidence for structural validity was adequate, with one study reporting a four-factor structure via Exploratory Factor Analysis. This instrument provided a clear definition of the dating relationship, the period of time under consideration is well delimited, and measures behaviors on all digital devices and digital platforms. The items are related to four dimensions of CDV (Cyber psychological aggression, Cyber control, Public harassment, and Cyber sexual). This instrument is very promising for assessing CDV abuse in old adolescents and young adults, although it should be noted that it was applied in Australia only. Thus, its application should not be recommended in other languages or countries.

Abuse in Teen Relationships (CARPA; Calvete et al., Reference Calvete, Fernández-González, Orue, Machimbarrena and González-Cabrera2021). One psychometric study examined the measurement properties of the CARPA (Calvete et al., Reference Calvete, Fernández-González, Orue, Machimbarrena and González-Cabrera2021) based on a sample of Spanish adolescents (11–18 years). Moderate-quality evidence supporting content validity was found. The quality of the evidence of structural validity was very good, with a two-factor structure applying Confirmatory Factor Analysis. This instrument is a subscale inside a more complete instrument assessing all kinds of abuse in dating relationships, so it is more reduced than the other two instruments. It included 11 items related to four dimensions of CDV (Cyber psychological aggression, Cyber control, Public harassment, and Cyber sexual). This instrument showed good measurement properties and it is promising, but it has only been applied in Spanish samples, so adaption studies should be done to prove its suitability for other contexts.

Discussion

CDV is a relatively new line of research, and there is no consensus regarding its conceptualization, a situation which has led to the development of multiple and different tools to measure it. The assessment of CDV shows a great methodological diversity (Rodríguez-Domínguez et al., Reference Rodríguez-Domínguez, Pérez-Moreno and Durán2020), and the objective of this study was to realize a systematic review of the CDV literature, describe the measurement tools that have been developed in recent years and, finally, identify the best instruments based on their methodological quality. It is hoped this paper will help scholars in choosing an appropriate instrument for their research.

In this systematic review, up to 24 different measurement tools were found, along with 29 psychometric studies about these instruments, all presenting differences in methodological characteristics such as sampling context, psychometric properties provided, and dimensions studied. This variability in the measurement tools is not new as it had already been seen in previous reviews (Brown & Hegarty, Reference Brown and Hegarty2018; Caridade et al., Reference Caridade, Braga and Borrajo2019; Cavalcanti & Coutinho Reference Cavalcanti and Coutinho2019; Rodríguez-Domínguez et al., Reference Rodríguez-Domínguez, Pérez-Moreno and Durán2020). However, this paper includes some new instruments developed in recent years, and provides a deep evaluation of the psychometric properties of the measurement tools and its methodological quality following the COSMIN guidelines (Table 3) in order to formulate recommendations regarding their use. Despite the numerous instruments and psychometric studies found by this review, many development and content validity studies did not report a systematic process of how items were produced or selected, did not involve target population or experts, or did not provide sufficient detail (such as items, recall period, and response options).

After the evaluation of ten indicators of methodological quality as well as the eight indicators assessing the reported psychometric properties quality, seven selected instruments were classified as category A (Prinsen et al., Reference Prinsen, Mokkink, Bouter, Alonso, Patrick, de Vet and Terwee2018), and three instruments were determined as the most suitable for the measurement of CDV: Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire (Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda, et al., Reference Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda and Calvete2015), Technology-facilitated Abuse in Relationships Scale (Brown & Hegarty, Reference Brown and Hegarty2021), and Abuse in Teen Relationships (CARPA) (Calvete et al., Reference Calvete, Fernández-González, Orue, Machimbarrena and González-Cabrera2021). The Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire could be considered as the best instrument because it shows good-quality evidence in its psychometric properties, with consistent evidence of four psychometric studies based on adolescents and young adults and adapted to four cultural contexts (Spain, Portugal, Chile and Mexico). Thus, this instrument is recommended for assessing CDV in adolescents older than 14 and young adults. The Technology-facilitated Abuse in Relationships Scale stands out for having high-quality evidence supporting content validity. Moreover, it measures CDV behaviors on all digital devices and includes four dimensions. However, it was only applied to an Australian context. The Abuse in Teen Relationships scale has a cyber subscale with eleven items and can be applied to adolescents of all ages, but adaption studies should be done to prove its suitability for non-Spanish contexts. Nevertheless, no selected instrument assessed or provided psychometric evidence to support cross-cultural validity, reliability, criterion validity, or responsiveness.

The search in the present study was limited by focusing only on scientific articles, by excluding measures that investigate only one CDV behavior and those studies focused on subjects older than 30 years, which may have resulted in relevant contributions to the review being overlooked. COSMIN is a rigorous methodological tool, but there is a certain level of subjectivity in rating each paper (Cassidy et al., Reference Cassidy, Bradley, Bowen, Wigham and Rodgers2018). Thus, the process of evaluation of psychometric properties of 24 instruments is transparent, and the global rating of instruments was elaborated by consensus between two evaluators considering the information in Table 3.

Digital media such as cell phones and social networks have had a favorable impact on romantic relationships, since couples can keep in touch when they are not face to face, allowing the perception of greater closeness (Javier-Juárez et al., Reference Javier-Juárez, Hidalgo-Rasmussen, Díaz-Reséndiz and Vizcarra-Larrañaga2021). However, digital media can also have a negative impact in dating relationships because they provide new channels to exercise harassment, control and abuse (and therefore to suffer them), in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood (van Ouytsel et al., Reference Van Ouytsel, Walrave, Ponnet, Willems and Van Dam2019). There is no agreement regarding the conceptualization of CDV. This paper defends the use of the term cyber dating violence, and the definition includes different types of dating aggression using digital media (psychological direct, control, public harassment, exclusion, and sexual). Exclusion (excluding, or blocking on social networks) is the least assessed dimension among the instruments analyzed. Although previous reviews (Brown & Hegarty, Reference Brown and Hegarty2018; Caridade et al., Reference Caridade, Braga and Borrajo2019; Cavalcanti & Coutinho, Reference Cavalcanti and Coutinho2019; Rodríguez-Domínguez et al., Reference Rodríguez-Domínguez, Pérez-Moreno and Durán2020) have already shown the variability of the used instruments and their methodological approaches, the present review analyzed the quality of psychometric properties using the COSMIN checklist. Thus, this systematic review can help researchers to assess CDV and clinicians to focus on the evaluation programs. Among the three tools recommended, the Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire (14−30 years) obtained the highest total sufficient rating.

Some studies argue that, although online and offline violence present some similarities in terms of habits and attitudes, violence through virtual contexts shows certain particular characteristics that should be addressed in a specific way (Núñez et al., Reference Núñez, Álvarez-García and Pérez-Fuentes2021). Thus, it is important to understand the negative use of technology in intimate relationships, as well as the differences and similarities between online and offline violence, in order to be able to support adolescents and young people during this important stage of their lives, and to advance in the creation of effective and specific prevention and treatment programs. Early detection of CDV could be very relevant; therefore, it is essential to provide a reliable and valid evaluation instrument. Although the communication is virtual, the relationships, their effects and consequences are real. What happens online is not something merely virtual since it has real effects on people and can cause more depressive moods (Cava, Buelga et al., Reference Cava, Buelga, Carrascosa and Ortega-Barón2020) and a significant deterioration of life quality. Future studies could focus on analyzing reliability, criterion and cross-cultural validity of the existing instruments.

Appendices

Appendix A: Studies which Have Applied some CDV Instruments but are not Psychometric Studies

Appendix B