Introduction

On December 30, 1969, Richard M. Nixon signed the Tax Reform Act of 1969 (TRA69) into law. TRA69 coupled tax-relief measures for almost all income classes with several major structural reforms that broadened the tax base by restricting and eliminating tax preferences and loopholes for high-income taxpayers and businesses. It also included a temporary income tax surcharge for the first six months of 1970 (Congressional Quarterly 1970: 589). When he signed TRA69, Nixon emphasized that most of his proposals had been adopted, which would make the federal income tax system simpler, fairer, and more equitable, while reducing the tax burden of most taxpayers and encouraging investments in the long term. In the face of expanding budget deficits and rising prices, however, the tax reform fell approximately $3 billion short of his original proposal. “The effect on the budget and on the cost of living [that TRA69 would provide] is bad,” Nixon stated. He worried that the tax reform might impose a ceiling on “[g]overnment revenues in future years, limiting our ability to meet tomorrow’s pressing needs.” Meanwhile, he emphasized that “[t]he tax reforms, on the whole, are good … it is a necessary beginning in the process of making our tax system fair to the taxpayer” (Nixon Reference Nixon1969b).

TRA69 resulted from the efforts of the Department of Treasury and tax experts to accomplish a long-overdue goal of creating a simple, fair, and equitable federal income tax system with the capacity to raise revenue. Since World War II, the federal tax system had heavily relied on high-rate progressive income taxation, the so-called punitive mass-based wartime taxation that had included most middle-class wages and salaries.Footnote 1 The tax system also paved the way for a proliferation of tax loopholes and preferences—popularly known as “tax expenditures”—that favored recipients of unearned income and higher income classes. This “tax favoritism” undermined statutory tax rates, eroded the breadth of the tax base, and made the federal income tax system complicated and inequitable among income types and classes (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2016). In the 1960s, the US Treasury and tax experts attempted to reform the “mass-based wartime taxation” and tax favoritism by lowering the rates of individual and corporate income taxes to reduce the tax burden of low- and middle-income classes while reducing and eliminating unfair tax loopholes and preferences. Their goal was a one-package tax reform that combined base-broadening reforms with a rate structure reform based on the concept of “comprehensive income”: “[T]he money value of the net accretion to one’s economic power between two points of time” (Haig Reference Haig1921: 7–27). The Treasury and tax experts agreed that tax reform based on the concept (hereinafter, comprehensive income tax reform) would make the federal income tax system fairer, simpler, and more equitable both horizontally (the same tax liability for any taxpayer with the same level of income) and vertically (the appropriate sharing of tax burdens among different levels of income), with sufficient ability to raise revenue. Their efforts to accomplish this goal were once defeated by two tax cuts of John F. Kennedy, in 1962 and 1964 (Mozumi Reference Mozumi2016, Reference Mozumi2018a). Still, the Treasury continued its research during Lyndon B. Johnson’s presidency, which eventually led to Nixon’s enactment of TRA69.

Many scholars discussing TRA69 have evaluated that it succeeded in overcoming the political difficulties, shifting the tax burden from lower and middle-income classes, and enhancing the equity of the federal tax system horizontally and vertically. They have also argued that TRA69 elevated the popularity of loophole-closing tax reforms, inspiring liberal activists and think tanks to pressurize Congress into enacting further tax reforms (Bartlett Reference Bartlett2012; Ippolito Reference Ippolito2012, Reference Ippolito2015; Michelmore Reference Michelmore2012; Steuerle Reference Steuerle2008; Thom Reference Thom2017; Witte Reference Witte1985; Zelizer Reference Zelizer1998). However, several studies have demonstrated that TRA69 primarily provided opportunities to decorate a tax-cut Christmas tree, or a wartime tax cut championed by liberal Democrats in Congress (Bank et al. Reference Bank, Stark and Thorndike2008; Brownlee Reference Brownlee2016; Witte Reference Witte1985). Most of the scholars agree that the Treasury and its staff, led by a tax law scholar, Stanley S. Surrey, and Representative Wilbur D. Mills, a southern Democrat from Arkansas who led the House Committee on Ways and Means (CWM), played a crucial role in drafting and passing TRA69. They have also demonstrated that while congressional Democrats supported their efforts, Johnson was unlikely to propose the tax reform, particularly the cuts in tax preferences for the oil and gas industry, the main industry of his home state, Texas, because he obtained support from them.

This article demonstrates two main points neglected by previous studies about TRA69. First, although TRA69 partially succeeded in horizontally and vertically enhancing tax equity while reducing the tax burden of low- and middle-income classes, it did so through a short-term tax increase. Second, the result of TRA69 was provided by the conflict among various perspectives of the tax reform proponents—the Treasury, Mills, and congressional Democrats. Although TRA69 implemented many tax-relief measures for low- and middle-income classes, its tax-increase elements fueled the anger of the working- and middle-class taxpayers, who had already suffered inequitably from progressive rate structure and increasing tax burdens in the face of inflationary pressure, against federal taxation and intensified their sense of injustice. Notably, it led both Congress and administrations after the 1970s to introduce more tax preferences for the angry and dissatisfied taxpayers. TRA69 was a “missed opportunity” in terms of beginning the process of improving the fairness of the federal tax system and alleviating tax favoritism after the 1970s. The remaining tax favoritism has undermined taxpayer consent to and confidence in the American fiscal state. It also diminished the possibility of further tax reforms to finance the federal government and enhance the equity of federal tax system both horizontally and vertically.

Tax Reform Efforts of Surrey and Mills until 1961

The effort to achieve a comprehensive tax reform in the 1960s was a continuation of an even earlier effort of the Treasury and Congress from the 1930s. A tax law scholar, Stanley S. Surrey, had significantly contributed to the tax reform development as early as the 1930s, continuing into the 1960s. After graduating from Columbia University Law School in 1932, Surrey joined the administration of Franklin Roosevelt and subsequently the Treasury’s Tax Legislative Counsel the following year. After becoming a law professor in 1947 at the University of California, Berkeley, he joined the American Tax Mission to Japan under the chairmanship of Carl Shoup of Columbia University, the “Shoup Mission.” It aimed to reform the Japanese tax system based on the “comprehensive income” concept to make it more equitable and efficient (Brownlee et al. Reference Brownlee, Elliott and Yasunori2013). After the Shoup Mission, Surrey became a law professor at Harvard Law School in 1951, and convened numerous conferences for economists and tax lawyers to discuss the federal tax system (Surrey 1956 HLSL/HSC/SSSP). In the late 1950s, he advised the CWM on tax reform proposals (Surrey to Mills 1958 HLSL/HSC/SSSP). Throughout these activities, he emphasized that tax reform based on the concept of comprehensive income should promote fairness, simplicity, and horizontal and vertical equity. He believed that the federal tax system should allow for more equity in the tax burden, according to the type and level of income horizontally, and should smooth the rate structure without sacrificing vertical equity and tax revenues.

While Surrey made significant efforts to accomplish a comprehensive income tax reform, congressmen and congressional staff also focused on constructing an equal, fair, and simple federal income tax system. Among them, Wilbur D. Mills (Democrat—Arkansas), a very senior and politically talented Representative, significantly contributed to this discussion. In 1938, Mills successfully ran for Congress, becoming a member of the CWM in 1942. After he began chairing the Tax Policy Subcommittee of the Joint Committee on the Economic Report (JCER) and the Joint Committee on Internal Revenue Taxation of the CWM in 1954, he gained the confidence of both parties concerning federal tax policy, as he was one of the few congressmen that did not rely on professional advice to understand tax proposals. During the administrations of Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower, however, federal tax reforms until 1954 increased loopholes that should have been abolished while leaving a steep progressive rate structure (Brownlee Reference Brownlee and Elliot Brownlee1996; McClenahan and Becker Reference McClenahan and Becker2011). Then, in the mid-1950s, Mills began leading the effort to accomplish comprehensive income tax reform by cooperating with many well-trained tax scholars, including Surrey.Footnote 2 Based on his experience with the JCER and the CWM, Mills learned that broadening the income tax base, according to the rule of “ability to pay,” by simultaneously cutting tax preferences and eliminating advantages that the average taxpayers did not enjoy, tax rates could be reduced and the tax burden could be distributed more fairly without losing revenue, increasing public debt, aggravating inflation, and reducing government expenditures (Cassels Reference Cassels1956). After Mills assumed the chairmanship of the CWM in 1958, he appointed economic experts, political parties, business leaders, and Treasury staff, including Surrey, who was a keynoter to attend a series of hearings, from November 16 to December 18, 1959, where they discussed specific tax-reform proposals and promoted the necessity of tax reforms to the public.

At the panel, Surrey explained that preferential treatment for certain types of income created an unduly narrow tax base and allowed taxpayers, particularly higher income taxpayers, to avoid paying their fair share. He also pointed out that the narrowed tax base provided excessively high marginal rates for raising revenue, low effective rates, and a severely discriminatory tax burden across various types of income imposed on some taxpayers, especially those in the middle-income bracket. Based on the concept of comprehensive income, Surrey argued that lowering and smoothing the tax rate structure and eliminating unjustifiable tax preferences for the upper-bracket would reduce the tax burden of lower and middle-income classes, improving comprehensively fairness, simplicity, and the horizontal and vertical equity of the tax system without revenue losses (Surrey 1959 HLSL/HSC/SSSP). After the hearings, the CWM concluded that Surrey’s idea would be the foundation of tax reforms for administrations in the 1960s (CWM 1959). The Treasury and the CWM concurred that the tax reform plan would be essential to tax fairness and promoting desirable economic or social objectives (Scribner, Jr. to Mills 1959 NACP/OTPSF).Footnote 3

During the 1960 presidential campaign, Democrats and their presidential candidate, John F. Kennedy, added a tax reform plan into their agenda based on Surrey’s tax idea and the CWM’s 1959 conclusion (Kennedy Reference Kennedy1960a, 1960b, 1960c). The Democratic circle had issued statements arguing that a Democratic victory would bring American taxpayers an overhaul of the federal income tax law. They made average taxpayers believe that Kennedy would realize a tax plan to comprehensively reform the federal income tax (Sullivan to Kennedy 1960 NA/JCIRT). After Kennedy won the presidential election, he appointed Surrey as the chairman of his Pre-presidential Taxation Task Force, which worked to devise this tax reform plan.Footnote 4 On the last day of 1960, the Task Force finally recommended a tax reform combining base-broadening reforms with rate reductions based on the “ability to pay” and the concept of comprehensive income. They expected that it would win taxpayers’ acceptance by emphasizing its broader and more uniform tax base, appropriate rate structure, enhanced horizontal and vertical equity, and the reduced tax rates that entailed no revenue losses. The Task Force emphasized that associating tax base reform with rate reductions as “a single comprehensive [income tax reform] program … significantly differentiates this approach from the usual ‘loophole-closing’ campaign” that ideologically contended that the wealthy had unfairly obtained income so that tax reform should reduce or eliminate the tax preferences that benefitted them (Taxation Task Force 1960 JSKL/JFKPPP). After Surrey became Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Tax Policy, the Treasury, led by Surrey and the Office of Tax Analysis (OTA) of the Treasury, drafted a coherent, revenue-neutral tax reform package aligned with the Task Force’s recommendation (Surrey 1961 JFKL/WWHPP). In 1961, the idea of the CWM and the Treasury still prevailed in the Kennedy administration (Okun to Solow and Pechman 1961 HLSL/HSC/SSSP; Solow to Heller, Gordon, and Tobin 1961 HLSL/HSC/SSSP).Footnote 5

The CEA and the Defeat of Comprehensive Tax Reform, 1961–1964

During the Kennedy presidency, the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) in the White House was influential in federal tax policy decision making. Kennedy’s CEA members—Chairman Walter Heller, James Tobin, and Kermit Gordon—considered tax ideas other than those of Surrey and Mills.Footnote 6 To them, the most important economic problem was the gap between actual output and a “full-employment output,” the output assumed when an economy is at full employment. At the beginning of the 1960s, they estimated that the federal tax system could increase revenue by $7–8 billion annually under normal economic conditions. In a slack economy, however, a “fiscal drag,” as Heller called it, would frustrate any change of economic expansion. In response, the CEA used the concept of a “full-employment budget surplus,” the difference between the balance of the actual budget and the full-employment budget, to suggest that the “fiscal drag” should be offset by “fiscal dividends” through tax cuts or increased government expenditures, even in the face of the actual budget deficit (Heller Reference Heller1967: 60).

Based on the concept of the “full-employment budget,” the CEA of Kennedy interfered with the efforts of the Treasury, Surrey, and Mills. From 1961 to 1962, to relieve the fear of a recession by offsetting the fiscal drag, the CEA recommended that Kennedy should propose the tax reform program the Treasury had drafted in 1961 as a net tax cut by dividing it into two parts: the permanent rate cuts and simple tax-cutting measures would take effect first; then, a year later, controversial base-broadening reform measures should take effect (Heller to Kennedy 1962 JFKL/WWHPP). Although the Treasury and Mills did not favor this approach, they accepted it after negotiations (Wallace 1962 JFKL/RDTMPO). When Kennedy sent Congress his tax reform program in 1963, it was a huge tax cut according to the CEA’s recommendation (Kennedy Reference Kennedy1963). However, when Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, finally signed the tax reform program into law on February 26, 1964, the tax reform bill consequently included huge rate cuts in individual and corporate income taxes but almost no reform measures. It was, in general, little more than a huge tax cut just as the CEA wanted, becoming known as the “Kennedy–Johnson tax cut” of 1964. It embedded within the idea of fiscal policy, which Herbert Stein had once called “domesticated Keynesianism,” that taxing and spending were tools for controlling macroeconomic conditions rather than meeting public demand (Mozumi Reference Mozumi2018a; Stein Reference Stein1969). The new legislation did not strengthen the horizontal and vertical equity of the federal tax system, which foiled the ambitions of the Treasury. The original impetus for comprehensive income tax reform had once vanished.

The Treasury Devises the Concept of “Tax Expenditure”

When it turned out that the Treasury would likely be defeated in 1964, they began another attempt to reverse the gradual erosion of the tax base created through the inclusion of social preferences and privileges for certain groups of taxpayers. On March 2, 1964, Henry H. Fowler, the Under Secretary of the Treasury, declared that the federal tax system should raise necessary revenues at the lowest possible tax rates while eradicating a number of long-standing flaws related to equity and simplification.Footnote 7 He emphasized that it would be a commendable switch from the old pattern of opening new “loopholes” with the inevitable result of increasing upward pressure on existing rates or passing up opportunities to reduce the rate scales (Treasury Department 1964 NACP/OTPSF). Fowler largely entrusted Surrey with accomplishing the long-desired tax reform within the Treasury alongside the new OTA director, Gerald M. Brannon.Footnote 8

Surrey and Brannon first elaborated a fundamental concept to judge whether a certain tax preference followed the Treasury’s policy to criticize the idea that it often created loopholes that could be used to attack social and economic problems effectively (Brannon 1964 NACP/OTPSF). Surrey, Brannon, and the OTA understood that tax preferences based on this idea, such as education and medical care, were unfairly and inefficiently providing large amounts of tax relief to higher income taxpayers rather than individuals and families who did not have enough income to take advantage of them. They also viewed that they had drained vital tax revenue (Stockfisch to Lamont 1964 NACP/OTPSF). Therefore, they regarded any tax preferences designed to further a specific, desirable social goal as the equivalent to “monies spent” to assess and judge whether it would enable the federal government to achieve its policy goals more efficiently, directly, and fairly, as compared to government direct expenditure programs.

Surrey and his colleagues in the Treasury believed that this primitive concept of “tax expenditures” would help the Johnson administration avoid wasting tax revenue that could instead be used to directly finance the expansion of the social programs—poverty, pollution, manpower training, health, and research and development programs—they had planned for those most in need as part of the “Great Society programs” (Treasury Department 1965a NACP/OTPSF). Thus, Surrey prioritized the tax policy goal of Johnson’s Treasury as eliminating poverty and improving the equity—both horizontally and vertically—and simplicity of the federal tax system by reducing the differences among the types of tax treatment through restricting or eliminating tax preferences and loopholes, particularly those benefitting the wealthy, and lowering the tax burden in ways of giving the most benefit to the poor (Treasury Department 1965b NACP/OTPSF). Although Surrey set the goal of tax reform based on the concept of tax expenditures by assuming the concept of comprehensive income with no significant revenue gains or losses in as fair and simple way as possible, it notably also aligned with the ideals of Johnson’s Great Society programs that sought to benefit the most vulnerable populations in the United States.

Tax Reform Versus Tax Increase, 1966–1967

While researching possible tax reform program, the Treasury worked on two ways of proposing countercyclical tax increase owing to the Vietnam War and inflationary pressure in late 1965. With a temporary across-the-board increase in tax rates, the Johnson administration sought to fulfill its international commitments, fight inflation, and maintain essential social programs. The administration’s views were based on the arguments of Johnson’s CEA members—Chairman Gardner Ackley, Otto Eckstein, and Arthur M. Okun—that such a temporary tax increase was necessary in the face of inflation and the full-employment budget deficit (Surrey to Fowler 1966 LBJL/PHF).Footnote 9 They focused on the possibility of a temporary surtax on individual and corporate income taxes of approximately $4–5 billion (Heller Reference Heller1967; Martin Reference Martin1991; Stein Reference Stein1969). Democrats contended, however, that Americans had already faced high state and local taxes, which had sharply increased the prices of essential items and caused hardships for the poor and middle-income taxpayers. Some of them also viewed any tax increase as a way to fund and accelerate the escalation of the Vietnam War. Then, they argued that Johnson should propose measures to close tax loopholes that had majorly benefitted high-income brackets and corporations as a desirable tax increase measure (Ottinger to Johnson 1966 NACP/OTPSF; Ottinger to Mills 1966 NACP/OTPSF).

Surrey, the Treasury staff, and Mills had varying opinions of how to treat closing-loophole reforms. Surrey and the Treasury staff separated any tax increase arguments from the Treasury’s tax reform program and ruled out the proposal of loophole-closing measures as temporary countercyclical tax increases. They were concerned that the tax increase suggested by Democrats would have highly uncertain economic effects, particularly in the short run, and provoke controversy that would considerably delay legislation (Surrey to Ottinger 1966 NACP/OTPSF). Even after Johnson proposed the temporary surtax on individual and corporate income tax on January 10, 1967, they believed that the tax reform recommendation should be postponed until the two tax-writing committees, the CWM and the Senate Finance Committee (SFC), finished discussing the surtax proposal (Surrey 1967 LBJL/PHF).Footnote 10 While Mills pointedly opposed Johnson’s temporary surtax proposal and demanded cuts in government expenditures as a prerequisite, he publicly promoted the importance of the tax reform that Surrey and the Treasury aimed to accomplish. Although Mills did not clarify which tax equity—horizontal, vertical, or both—he emphasized, he declared that all CWM members had agreed that the Treasury’s tax reform would enable the federal tax system not only to raise the necessary government revenues in a simpler, fairer, and more equitable manner but also to provide economic stability and growth to the private economy. In addition, Mills recommended that the Treasury should avoid delaying the recommendation of the tax reform bill for a discussion of the surtax proposal in Congress.Footnote 11

The Mills’s promotion of the Treasury’s tax reform coincided with the arguments of many Democrats about tax reform. In early 1967, extracting the closing-loophole aspect from the Treasury’s tax reform plan, they intensified their arguments for the proposal of mere closing-loophole measures to enhance the equity and fairness of the federal income tax system while financing the Vietnam War. They repeatedly emphasized that old and newly discovered tax loopholes had catalyzed the growing imbalance between the rich who were aided by trust companies and lawyers with intimate knowledge of the tax system intricacies, and the poor who had no such help. Congressional Democrats also predicted that people would be increasingly aware of the tax bite and the inequities that had been built into the topsy-turvy tax structure as the cost of the Vietnam War escalated and the prices increased (Childs Reference Childs1967).

As the Democrats’ arguments spread nationwide, newspapers began criticizing “ideas for more tax loopholes” as dangerous to the national budget and equivalent to providing “new loopholes in a tax law already as full of holes as a Swiss cheese.”Footnote 12 Many of them described how Johnson’s request for the surtax would affect low- and middle-income groups the hardest. The expansion of social expenditures by 1967—particularly of the number of families receiving the Aid to Families with Dependent Children—had rapidly increased costs to taxpayers and received increasingly critical public attention as a crisis of “confidence—of fear and alarm among taxpayers, of mounting frustration, ill-feeling and disorder in smoldering urban ghettoes, of widening disillusion among men of goodwill” (CWM 1967: 96). This intensified the whites’ hostility toward the nonwhites. Many conservative whites in the suburbs or the South commonly perceived they had unfairly paid more taxes than the nonwhites for a welfare system that catered to the nonwhites (Kruse Reference Kruse2005: 125–30). In this situation, the newspapers revived the idea that Johnson and Congress should force the wealthy and industries such as the oil and gas industry, which paid a lower effective tax rate on their income and profits than most industries, to pay more taxes and reduce the tax burden of others.Footnote 13 They spread the view that loophole-closing measures would overhaul the distribution of tax burdens and plug loopholes while simply raising additional tax revenues for the Vietnam War rather than a temporary surtax that would raise larger revenues from less-privileged taxpayers. Furthermore, they also made the average taxpayers believe that such reform measures would make other taxpayers carry their share of the tax load fairly.Footnote 14

The arguments of congressional Democrats and newspapers provoked taxpayers to argue for closing-loophole tax reforms as a means to prevent tax avoidance, restrict inflationary pressure, and finance social programs as well as the Vietnam War instead of Johnson’s surtax proposal. As constituents, they encouraged many Democrats, including Representative Wright Patman (Democrat—Texas) and Senator Robert Kennedy (Democrat—New York), to strongly support what they called “closing tax loopholes” as an alternative to the surtax proposal (Patman to Johnson Reference Johnson1967 LBJL/PHF).Footnote 15 As a CWM member, Democratic Representative James Burke (Democrat—Massachusetts) told The New York Times that many congressional Democrats were urging the Johnson administration to accomplish loophole-closing tax reforms in accordance with their constituents’ demands: “Why tax me more when you let some of the rich fat cats off scot free?”Footnote 16 Surrey and his colleagues had emphasized tax reform that would enhance both vertical and horizontal equity of the federal tax system. They devised the primitive concept of tax expenditures to accomplish this goal. Although Mills also argued for tax reform to enhance “tax equity” from viewpoints of the “ability to pay,” it was ambiguous which tax equity Mills intended to emphasize. As a result, the Mills’s argument induced the movements of the public and congressional Democrats that required loophole-closing reforms. They understood “loophole-closing” tax reforms—which Surrey had distinguished from his ideal comprehensive tax reform since 1960—as a measure to raise revenue while enhancing the equity and fairness of the federal tax system. The term “tax reform” popularly came to signify loophole-closing measures that would enhance vertical equity while raising revenue by forcing the rich and tax dodgers to pay their fair share rather than what Surrey and the Treasury had crafted and desired from their defeat in 1964.

Revenue and Expenditure Control Act of 1968 and the Tax Reform Proposal of 1969

Despite growing support for the loophole-closing reforms, the situation remained fluid until the end of 1968. During the autumn of 1967, Surrey and his colleagues within the Treasury continued inquiring about the effects, efficiency, and legitimacy of each tax preference, while the CWM committed to the administration’s surtax proposal. Shifting his perspective, Mills asked Surrey and the Treasury to postpone sending the tax reform program to Congress until 1968 because he did not want to become involved in any further tax matters in 1967 (Surrey to Fowler 1967 LBJL/PHF). By the end of 1967, the concept of tax expenditures had gradually become more popular among the public as revenues that were lost by virtue of the tax preferences Congress had granted to certain groups of taxpayers, or “government expenditures through the tax system.”Footnote 17 Even businesses, the largest beneficiary of tax preferences and the most significant advocate of expenditure cuts, considered that a tax reform based on the concept of tax expenditures would rank as the single most important tax idea of 1968 (Metz Reference Metz1968). In January 1968, thirty-one Democrats stated that they would not vote for the surtax bill unless it was accompanied by a tax reform bill (Bowman to Surrey 1968 LBJL/PHF). In the hearings before the CWM, several Democratic CWM members inquired Fowler that the Johnson administration should recommend the loophole-closing reforms as measures not only to improve vertical equity of the tax system but also to substitute Johnson’s surtax proposal. Fowler nonetheless expressed the Treasury’s unchanged attitude from 1966: the tax reform they had planned was to enhance tax equity both horizontally and vertically by diminishing inequality in the existing tax law and lightening the burden of the most vulnerable taxpayers (CWM 1968: 125–26). Furthermore, he repeatedly emphasized that the Treasury had been preparing “very substantial tax-reform proposals” to reform the federal tax system that he believed was “far from being equitable today” (Dietsch Reference Dietsch1968).

When the surtax proposal was finally legislated as part of the Revenue and Expenditure Control Act of 1968 (RECA) on June 28, 1968, it included a 10 percent surcharge on individual and corporate income taxes that would initially expire after June 30, 1969, and a ceiling on federal spending in 1969 of $180.1 billion to combat inflationary pressures. RECA also ordered the administration to submit the tax reform proposal that the Treasury had sent Johnson by the end of 1968.Footnote 18 It helped mollify a persistent bloc of Congressmen who called on Johnson to recommend tax reform along with or instead of a temporary tax increase. Mills stated that the tax reform would be the CWM’s top priority in 1969.Footnote 19 Given the expenditure cuts of RECA, the Johnson administration had few options other than defending their social programs targeted to the poor. Due to these fiscal conditions, RECA’s tax increases might add to the tax burden of the middle class and induce taxpayer’s revolt, making it more difficult to generate revenues for meritorious social programs (Brown Reference Brown1999: 257–62). During the presidential campaign in 1968, Richard M. Nixon employed a strategy of color-blind populism that celebrated the hardworking and middle-class taxpayers to evade the call for forceful government action to address segregation and racial inequality. Nixon expected that his strategy would resonate with white middle-class voters in the metropolitan South and nationwide (Nixon Reference Nixon1968). Nevertheless, in 1968 Johnson did not submit to Congress the tax reform proposals composed by the Treasury over the previous five years. On December 31, he announced that he would pass this responsibility onto the Nixon administration and Congress (Johnson Reference Johnson1968).

Shortly before Nixon took office, the impetus for tax reform peaked. The interim Secretary of the Treasury, Joseph Barr, had worked out an arrangement whereby the CWM and the SFC would request proposals from the Nixon administration. Barr was under substantial pressure from Congress to provide the data on how many the rich had avoided their fair share. Then, Barr called Mills to argue that he did not want to turn down the requests from Congress before he left the Treasury. Mills then convened a meeting of the Joint Committee on Internal Revenue Taxation. The new Secretary-designate of the Treasury for Nixon, David M. Kennedy, accompanied Barr to the meeting.Footnote 20 In the meeting, Barr, Kennedy, and Mills reached an agreement that the CWM would transmit a request to Kennedy for the information of tax reform recommendation and publish it as a CWM report. More importantly, appearing before the Joint Economic Committee of Congress on January 17, 1969, Barr warned Congress of an emerging “taxpayer’s revolt” of middle-class citizens spurred by increasing awareness of existing tax inequity and a tax system that allowed high-income taxpayers to pay little or no federal income taxes through tax loopholes while middle-income taxpayers bore the brunt of taxation.Footnote 21 To exemplify, he cited 155 “extreme cases” in which individuals with adjusted gross income in excess of $200,000 paid no federal income tax (JEC 1969: 4–7). The next day, Barr captured media headlines, and his warning made tax reform a major issue.Footnote 22 Barr’s statement matched the criticism swelling among the public about the inequality of the federal income tax system and temporary surtax. Consequently, Nixon’s Treasury forwarded the recommendations of tax reform, Tax Reform Studies and Proposals, to the two congressional tax-writing committees on February 5, 1969.Footnote 23

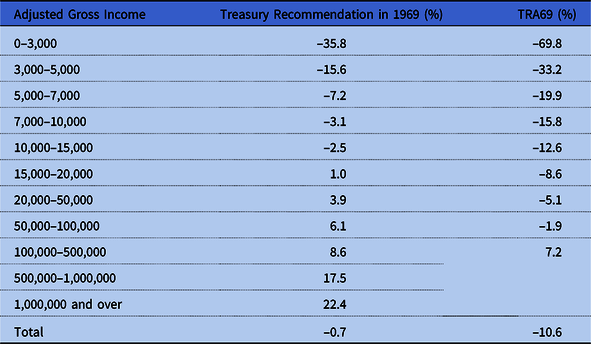

The Tax Reform Studies and Proposals compiled the results of the Treasury’s research and studies that Surrey and Brannon had directed from 1965 based on the concept of tax expenditures. The Treasury’s recommendations first intended to significantly reduce the tax burden on lower and middle-income taxpayers, particularly those below the poverty line.Footnote 24 To this end, the Treasury recommended several tax-relief measures, including an increase in minimum and ordinary standard deductions, personal exemptions, a “maximum income tax” to limit income tax payments to no more than 50 percent of a taxpayer’s earned income, and the expansion of moving expenses for employees. These recommendations also included many base-broadening measures to impose a fair tax burden on higher income classes who paid little or no income taxes, such as a “minimum income tax” that would place a 50 percent ceiling on an individual’s total income that could be excluded from tax payment, the allocation of itemized deductions between taxable income and nontaxable income, the correction of farm loss deduction abuses, and the reduction of capital loss deduction from 100 percent to 50 percent. Furthermore, the Tax Reform Studies and Proposals recommended measures to reform corporate income tax preferences, such as the treatment of mineral production payments, tax-exempt foundations, and multiple trusts. The Treasury’s recommendations would provide $420 million cuts in individual income tax and $155 million increases in corporate income tax, which would amount to a $265 million tax reduction overall. The individual income tax reform would lower the tax burden of low-income taxpayers and most in the middle-income taxpayers while increasing the tax burden of some middle-income taxpayers and higher income taxpayers (table 1). The reform plan aimed to alleviate the hardship of the poor and middle-class taxpayers while comprehensively enhancing the horizontal and vertical equity of the federal tax system (CWM and SFC 1969).

Table 1. The effect of the tax liability changes of TRA69

Source: JCIRT 1970: 14; SFC 1969: 34.

Note: The number of TRA69 excludes the effect of the extension of the surtax and the repeal of excise tax increases.

The public report of the Treasury’s recommendations shifted the conversation about tax reform to “both the White House and Capitol Hill must understand that a failure to enact reforms will increase the resistance to needed revenue measures and make more tax-cheaters out of otherwise honest Americans.”Footnote 25 In the first ten days of February 1969, the Treasury received more letters on the subject of tax reform than in all of 1968. Having a meeting with a ranking member of the CWM, John Byrnes (Republican—Wisconsin), and Mills, Nixon went over his tax reform recommendation and the timetable of when it should reach Congress.Footnote 26 On February 18, the CWM held hearings that Mills said “would be the most extensive hearings on tax reform in at least a decade.”Footnote 27 After the hearings, Mills suggested to the Nixon administration that coupling the repeal of the 7 percent investment tax credit with the extension of surtax would gain more than a hundred votes from Democrats. In a meeting on April 16, the new Under Secretary of the Treasury, Charls E. Walker, advocated the Mills’s recommendation.Footnote 28 He argued that social priority was not for stimulating investment spending but for helping cities, the disadvantaged, and the poor. He pointed out that the repeal of the investment tax credit would raise about $3 billion for these purposes as well as for dampening the investment boom fueling inflation. This would reduce the burden on low- and middle-income taxpayers, and fund Nixon’s important programs such as revenue sharing with state and local governments. Furthermore, Walker expected that the repeal might be the clincher in achieving the extension of the surtax that RECA had included (Walker to Nixon 1969 RMNL/WHCF/SF/FI). Following the meetings and the hearings, Nixon finally recommended a comprehensive tax reform bill to Congress on April 21, 1969.

Nixon’s tax reform proposal combined the recommendations of the Tax Reform Studies and Proposals to bring equity to the federal tax system with antiinflation fiscal policy based on the idea of domesticated Keynesianism. To scale down a number of tax preferences enjoyed by the wealthy, Nixon’s proposal included the 50 percent “minimum income tax” for citizens with substantial incomes on the use of tax preferences, the allocation of itemized deductions between taxable income and nontaxable income, the reduction and elimination of deductions for stock dividends, mineral transactions, farm losses, mutual saving banks, private foundations, charitable contributions, and tax-exempt organizations. Nixon also recommended the repeal of the 7 percent investment tax credit that would be effective retroactively from April 18, 1969. Nixon planned to use the revenue gained by these measures to provide tax-cutting measures for low- and middle-income taxpayers, including a “low-income allowance” that would remove low-income families from federal tax rolls, and the increase in standard deduction. In addition, Nixon recommended the extension of the full surcharge at 10 percent until January 1, 1970, with a reduction to 5 percent on January 1, 1971. Nixon addressed that the proposed tax reform would bring equity to the federal tax system and “serve the nation as a whole” with no substantial revenue gains or losses, reduce the burden of taxpayers who felt they were paying more than their fair share, and repeal “the tax of inflation” by the surtax with cuts in federal direct expenditures (Nixon Reference Nixon1969a). While the extension of the surtax would offset the revenue cuts of the Treasury’s recommendation, it would kill the tax-cutting effect for all taxpayers across the board.

TRA69: A Short-Term Tax Increase

In the CWM, Mills led the effort to modify Nixon’s tax reform proposal. He recommended that it include more base-broadening reforms such as a reduction in the current 27.5 percent oil depletion allowance.Footnote 29 He also promoted a trade-off for reducing tax preferences and slashing government expenditures to compensate for the revenue loss through substantial rate cuts.Footnote 30 During the CWM hearings, the resentment of American taxpayers against the “notorious loopholes” permitting “the wealthy to avoid taxes altogether or to pay far less than is warranted by their incomes” became known as a new political fact.Footnote 31 At the CWM hearings, labor organizations such as the United Auto Workers, the American Federation of Labor, and the Congress of Industrial Organizations, generally supported the Treasury’s proposals. They expected that the reform measures would raise revenues that would enable the administration to grant tax relief to low- and middle-income classes. Conversely, many business organizations such as the US Chamber of Commerce, the National Association of Manufacturers, the National Association of Real Estate Boards, the New York Stock Exchange, the US Savings and Loan League, and the American Automobile Association opposed most major Treasury proposals such as reforms of the oil and gas depletion allowance, capital gains, accelerated depreciation on real estate, interest on state and municipal bonds, and capital gains taxation.Footnote 32

Mills and the CWM admitted the labor organizations’ arguments but did not reflect the opposition from businesses to the CWM bill reported on August 2. The bill added to Nixon’s recommendation cuts in individual income tax rates from the current range (14–70 percent) to 5–50 percent for almost all taxpayers (effective 1971 and 1972), the low-income allowance, and the increase in standard deduction. The CWM bill also provided larger tax-relief measures than Nixon’s proposals, including simpler income-averaging provisions, moving expense deductions, and the “maximum income tax” the Treasury had recommended. The CWM bill eliminated and restricted many tax expenditures by the alternative maximum tax rate and other tax preferences on capital gains and losses, the repeal of the investment tax credit, the 50 percent “minimum income tax,” the restrictions of preferential treatments of stock dividends and interests, foundations, and the oil and gas depletion allowances. Furthermore, the bill extended the tax surcharge from January 1 to June 30, 1970, while Congress legislated the other half of the surtax extension from July 1, 1969 to the end of the year as H.R. 9951. The revenue effect of the CWM bill was almost neutral. The CWM emphasized that it would virtually restrict individuals from significantly escaping their tax payments while devoting all the revenue gains provided by the base-broadening measures to remove the general hardships of low- and middle-income taxpayers.

In the House Rules Committee (HRC), the CWM bill was challenged by House Democrats who required more tax-cutting measures for low- and middle-income taxpayers. During the HRC session, House Democrats criticized that the CWM bill gave more tax-relief benefits to low-income classes than to other taxpayers. The House Democratic Study Group argued that the bill left out middle-income taxpayers with annual income between $7,500 and $13,000. Mills then immediately called the CWM into another session to reach a compromise by adding tax-relief measures to the revenue-neutral CWM bill. The amendment added $2.4 billion tax reductions for almost all individuals with taxable income less than $100,000, where middle-income wage earners who received few tax breaks from the original CWM bill had belonged. Consequently, the amendment provided $9.3 billion annually in tax reductions and $6.9 billion in base-broadening reforms. The legislation would lose more revenue than it would produce, thereby threatening to increase deficits. In response to the concern, Mills justified the result by drawing on the logic of the 1964 tax cut that economic improvements derived from the bill would generate higher revenue in the long run, while warning of a “complete breakdown in taxpayer morale” and the federal tax system “based on ability to pay” if the tax reform was not enacted (Shanahan Reference Shanahan1969). Finally, Mills compromised with House Democrats by increasing tax-cutting measures. On August 7, the House passed its tax reform bill as a tax cut almost along with the CWM amendment.Footnote 33 However, the new Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Tax Policy, Edwin S. Cohen, stated publicly that the House-passed bill did not sufficiently succeed in closing loopholes for the rich.Footnote 34 The Nixon administration feared that the Cohen’s statement might further anger the average taxpayers so that it expected the Senate would restore closing-loophole measures to the bill (Dent to Nixon 1969 RMNL/WHCF/SF/FI).

The Senate nevertheless responded to the administration’s fear by weakening the closing-loophole reform aspects of the House-passed bill. At the SFC hearings, businessmen opposed the repeal of the investment tax credit. They feared that it would force them to file amended tax returns at considerable expense if it were not voted until 1970. The SFC bill eliminated the repeal of investment tax credits from the House-passed bill.Footnote 35 It also removed or reduced the loophole-closing provisions of the House-passed bill, including the “maximum income tax,” the elimination and limitation of preferential treatment for capital gains, the “minimum income tax,” the allocation of deductions between taxable and nontaxable income, the restrictions of tax preferences for private foundations, dividends, and interests, and the oil and gas depletion allowance. The SFC chose to compensate for revenue loss by shrinking loophole-closing reforms by adopting a higher-rate schedule than the House-passed bill (13–65 percent) for single persons.Footnote 36 On the Senate floor, further amendments were added to the SFC bill, such as the increase in Social Security benefits and personal exemption from $600 to $800 for each taxpayer and their dependents, and a host of new, widened, or reopened tax loopholes. Fifty-one Democrats—all but two who voted against the bill—supported the bill while Republicans were split, with 18 in favor and 20 against. The Senate bill passed on November 2 was essentially a huge tax cut shared by nearly all taxpayers that combined $3.32 billion loophole-closing provisions with $9.134 billion tax-relief measures in addition to Social Security increase.Footnote 37

Although Nixon considered a veto against the reform bills of the two tax-writing committees because they took the form of tax cuts in the face of inflation, he and his staff compromised and accepted the bills. The former vice president for Johnson, Hubert Humphrey, warned that the perception that the government had singled out their schools and neighborhoods for racial integration while their hard-earned tax payments subsidized the lifestyles of the rich, and the poor had spread among blue-collar white families (Lassiter Reference Lassiter2006: 302–03). On December 19, House-Senate conferees convened to resolve the House and Senate differences. Mills directed it. The conferees knew that not only would they have to dovetail the provisions of tax reform proposals into legislation that would satisfy the growing public demand for “meaningful reform” but also measure their final tax-reform bill by Mills’s standards. In response, the White House staff recommended to Nixon that a “veto would risk alienating such potent groups as the aged as well as a fair portion of the ‘great silent majority.’ A preferable course would be for the President to sign the bill, but to express his great disappointment with it” (Rose to Flanigan 1969 RMNL/WHCF/SF/FI). The new director of the Bureau of Budget, Robert Mayo, the new chairman of the CEA, Paul McCracken, and Kennedy also told Nixon that a veto “might impair your relations with Congress” and the public might interpret it “as denying taxpayers, especially low-income taxpayer … while protecting upper-income taxpayers against the loss of their loopholes” (Kennedy, Mayo, and McCracken to Nixon 1969 RMNL/WHCF/SF/FI). Consequently, both houses of Congress passed the House-Senate conference bill on December 22, and on December 30, 1969, Nixon finally signed it into law as TRA69.Footnote 38

TRA69 succeeded in massively overhauling the tax base worth $3.32 billion in the long run. On the one hand, it coupled base-broadening reforms such as the reduction of the 27.5 percent gas and oil depletion allowance to 22 percent, a 10 percent minimum income tax on most kinds of tax preference income exceeding $30,000, a $50,000 ceiling on the amount of individual capital gains eligible for the alternative capital gains tax rate of 25 percent while raising capital gains taxes from 25 to 30 percent for corporations and 35 percent for individuals above $50,000, and a 4 percent audit tax on the investment income of private foundations. TRA69 also repealed the 7 percent investment tax credit. When fully effective, these measures would provide $6.6 billion revenue increase in a year while closing tax loopholes for high-income classes over $200,000 and businesses. On the other hand, TRA69 also contained $9.1 billion of income tax relief, including personal exemption increase from $600 to $750 between July 1, 1970 and 1972, the low-income allowance designed to remove 5.5 million low-income taxpayers from the tax toll, the increase in the maximum standard deduction from 10 percent of income with a $1,000 ceiling to 15 percent with a $2,000 ceiling to be fully effective in 1973, cuts in tax rates for single persons effective in 1971, and the 50 percent maximum income tax rate on earned income. TRA69 provided tax reductions for almost all income classes, except the income class over $100,000. The benefits of tax reductions were more incidental to low- and middle-income classes than high-income classes. In the meantime, TRA69 enhanced the equity of the federal tax system vertically and somewhat horizontally for middle- and high-income classes (table 1). Subsequently, Nixon and Congress evaluated TRA69 as the most comprehensive reform of the nation’s tax statutes in history.Footnote 39

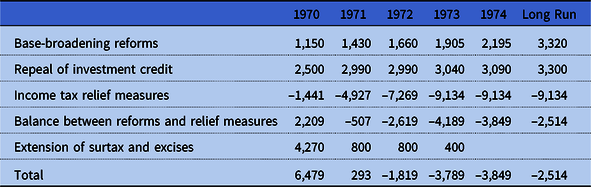

No matter how largely Nixon and Congress applauded TRA69 as successful, they neglected the fact that the Treasury had recommended more base-broadening provisions than it provided. Both Representatives and Senators—particularly, House Democrats and SFC members—presented tax reforms as involving tax-relief measures that would benefit the public, especially low-income and middle-class taxpayers. Although Mills had emphasized the principle of the “ability to pay” and restored several reform measures in the House-Senate conference, he also believed in the importance of rate cuts in and relief measures for individual income tax to “sell” the tax reform to taxpayers in the House as it would reduce the burden of almost all taxpayers. The tax reductions of TRA69 were significantly larger than the revenues raised by the base-broadening reforms because they lowered the tax burden of higher-income taxpayers while reducing the proposed base-broadening measures such as the 50 percent minimum income tax proposal to the 10 percent version. By sacrificing tax revenue in the long term and some of the base-broadening measures that the Treasury had recommended, Congress legislated TRA69 as the largest tax cut since 1964 (tables 1 and 2).

Table 2. Revenue effects of TRA69—calendar year 1970–1974 and long run (in millions of dollars)

Source: SFC 1969: 33.

Although TRA69 was achieved as a long-term tax cut, in the short term, it was enacted as another wartime tax increase because of the extension of the surtax at a 5 percent rate for the first half of 1970, the postponement of scheduled reductions in excise taxes on telephone services and new automobile purchase exchange services, and the gap of the effective dates between tax-relief and tax-increase measures. The act made most revenue-raising measures effective earlier than tax-relief measures (table 2). Although TRA69 reduced the surtax rate from 10 to 5 percent in 1970, the extension would continually impose an additional tax burden on all taxpayers who had already suffered from the 10 percent surcharge of RECA. Furthermore, for withholding tax purposes, the surcharge was taken into account at a 5 percent rate with respect to wages and salaries paid during the period. As a result, TRA69 would increase federal tax revenue by $6.5 billion in 1970, and $0.3 billion in 1971. In the short term, TRA69, combined with H.R. 9951, coercively imposed additional tax burdens on all taxpayers, particularly middle-class taxpayers who contended with the inequality of federal taxation and the tax avoidance of the wealthy (JCIRT 1970: 186–87).

Concluding Remarks: The Aftermath of TRA69

Soon after Nixon signed TRA69 into law, his administration attempted to sell it as a measure that provided tax reductions for low- and middle-income taxpayers while enhancing tax equity and raising revenue to offset revenue loss and counteract inflation to some extent through base-broadening measures. Nixon’s staff such as the Staff Assistant to the President, Noble M. Melencamp, and Press Secretary to the President, Ronald L. Ziegler, appealed to taxpayers that more than $9 billion in tax relief, when fully effective, would be heavily concentrated in the low- and middle-income brackets, while base-broadening reform measures would impose a fairer share of the burden on many high-income persons who had paid little or no tax in the past. Nixon’s staff also emphasized that TRA69 would benefit most taxpayers and have a major impact in making the tax laws fairer. In addition, they appealed that they planned to continue working on tax reform and therefore needed “the support of concerned citizens in making this a better place to live and work” (Ziegler to Fink 1970 RMNL/WHCF/SF/FI; Melencamp to Maciejewski 1970 RMNL/WHCF/SF/FI). In response to their attitude, congressional Democrats recommended that Nixon consider the possibility of more tax-reform proposals to “complete the job of loophole-plugging” (Reuss to Nixon 1970 RMNL/WHCF/SF/FI).

Middle- and working-class taxpayers did not uniformly agree with these appeals (Linn, Jr. to Nixon 1970). Rather, some of them regarded TRA69 as a complicated tax reform that exploited and misused their money for politicians and aimed to make it obscure. For instance, Clyde W. Rupert, from Dwight, Illinois, criticized Nixon for failing in increasing personal exemption and making it fully effective on January 1, 1970 as he had proposed. Although TRA69 included several base-broadening measures, Rupert argued that Nixon “signed this bill for the rich” while increasing his salary and that of Congressmen, effectively “stealing money from the poor working people [who would now] starve in this country” (Rupert to Ziegler 1970 RMNL/WHCF/SF/FI). In a letter to the Nixon administration, John G. Rauch, a tax attorney, argued that TRA69 had attained “a degree of complexity which can only be described as obscene,” forcing taxpayers to comply with its provisions because it was too complicated to understand (Rauch to Kissinger 1970 RMNL/WHCF/SF/FI). Expressing their dissatisfaction with TRA69, many middle- and working-class taxpayers, who called themselves “the undersigned petitioners, U.S. citizens and taxpayers,” sent letters in their joint name to request Nixon to carry out another reform of the federal public finance system. They expressed how deeply they were “distressed at the disproportionate share of our taxes which go directly to military and defense-related expenditures while we see our cities deteriorate, our education system inadequately funded, more and more of us on the rolls of the unemployed and millions of our own people without shelter and starving.” They also complained that they were nevertheless paying their “taxes under duress” of the federal tax system that overtaxed “citizens to the point of discouragement or outright rebellion.” Then, they strongly urged Nixon to consider a complete, immediate reordering of national priorities, warning that they would protest his administration if he failed (13 Taxpayers to Nixon and Congress of United States of America 1970 RMNL/WHCF/SF/FI; 22 Taxpayers to Nixon 1970 RMNL/WHCF/SF/FI).

These pressures led both Republicans and Democrats to demand more tax cuts from the Nixon administration for the dissatisfied taxpayers. In July 1971, 13 Democratic Senators asked Nixon to consider moving up the “income tax cuts presently scheduled for 1972 and 1973 [by TRA69] … to this year.”Footnote 40 Nixon agreed to this requirement. On December 9, 1971, he signed the Revenue Act of 1971, another tax reduction, into law. The 1971 act accelerated the increases in minimum standard deduction, personal exemption, and standard deduction that had been scheduled to take effect in 1972 and 1973. However, half the tax reductions provided by the 1971 act benefitted businesses because of the reintroduction of the investment tax credit.Footnote 41

It seems that the pressure from middle- and working-class taxpayers also dissipated the possibility that the Nixon administration would introduce a value-added tax (VAT) at the federal level. The Nixon administration considered the VAT as a candidate to partially substitute for local property taxes used to fund public schools. The necessity of balancing the 1971 fiscal budget was another important reason why Nixon asked the Treasury Department to craft a comprehensive proposal of the VAT. However, a 1972 survey by George Gallup reported that among 1,614 adults, 51 percent opposed a national sales tax, 34 percent approved it, and 15 percent had no opinion.Footnote 42 Democrats, who opposed the VAT for its regressivity, attempted to force Nixon to reveal a VAT reform agenda to gain a political advantage in the 1973 election. Although this strategy failed to prevent Nixon’s return to office, in November 1972, his administration resultantly dismissed the VAT reform because they feared that it “would raise too much revenue too fast” and would lead to a rise of federal spending and the growth of government.Footnote 43 Unlike West European countries such as France and Germany, or Scandinavian countries, this choice resulted in ruling out a measure that would have potentially financed social programs to support the poor and middle-class taxpayers.Footnote 44

The results of TRA69 and Nixon’s subsequent tax policies seemingly left fewer choices for most of his successors but to provide tax cuts and tax expenditures to benefit the public and gain political support from the middle class. While the economy faltered in the mid-1970s, the large, unlegislated tax increases for most individual taxpayers—the “bracket creep”—pushed not only the wealthy and middle-income class but also many lower income individuals into higher tax brackets even though their income had not increased. The growing tax burden made American citizens hostile toward federal taxing and spending (Michelmore Reference Michelmore2012: 1–3, 70–71, 93). The administrations of Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter in the late 1970s expanded the role of tax expenditures as a critical avenue to benefit working- and middle-class families (Biven Reference Biven2003; Mozumi Reference Mozumi, Huerlimann, Brownlee and Ide2018b; Witte Reference Witte1985: 179–98). By the late 1970s, however, a wave of taxpayer revolts had spread across the country in a different way than Barr had anticipated: taxpayers demanded tax cuts and maintenance of tax privileges they had received, while arguing for cuts in social expenditures. This movement led to one of largest tax cuts in US history, the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (Martin Reference Martin2008). Later, Ronald Reagan’s tax reforms in 1982, 1984, and 1986 rolled back the expansion of tax expenditures and enhanced horizontal equity by broadening the tax base.Footnote 45 However, Bill Clinton’s Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 and George W. Bush’s tax cuts in 2001 and 2003 mainly benefitted the wealthy by cutting taxes on capital gains, estates, and gifts. These tax cuts negated the effects of the tax reforms of 1982, 1984, and 1986 (Brownlee Reference Brownlee2016: 210–16; Steuerle Reference Steuerle2008: 161–98).

Although the use of tax expenditures has expanded since the 1970s (Howard Reference Howard1997; McCabe Reference McCabe2018; Pierson Reference Pierson, Levin, Landy and Martin2001), it has also narrowed the tax base, consumed considerable federal tax revenue available for government expenditures, complicated the federal tax system, benefitted the wealthy rather than low- and middle-income classes, and hidden from the public eye the federal approach to provide benefits for them (Faricy Reference Faricy2015; Mettler Reference Mettler2011). The complexity of the federal tax system and the regressive distributing effect of tax expenditures have made low- and middle-income taxpayers believe that those with superior knowledge of navigating tax loopholes—particularly the wealthy—have avoided their fair share while leading the middle- and high-income classes to believe that the poor and low-income classes have received benefits from the federal tax system and social programs without working and paying taxes (Williamson Reference Williamson2017). The invisibility of tax expenditures has induced the “government–citizen disconnect”—Americans do not recognize the expanding role of the federal government through tax expenditures, resulting in their assessment that the government does not work for them (Mettler Reference Mettler2018). As a result, TRA69 left “tax favoritism,” which has historically redistributed fiscal resources regressively while exhausting the tax revenues available for government spending. Thereby, it weakened taxpayer consent to and confidence in the legitimacy of federal taxation as a collective fiscal bargain in which taxpayers surrender their financial resources when they believe that taxation fairly reflects the cost of public goods and treats all taxpayers equally (Levi Reference Levi1988; Martin et al. Reference Martin, Mehrotra and Monica2009; Steinmo Reference Steinmo2018). The undermined taxpayer consent has resulted in the weak extractive capacity and welfare provisions of the American fiscal state.Footnote 46

Acknowledgments

I presented the preliminary version of this article at a session of the annual meeting of Social Science History Association on November 21, 2019. I am grateful for the comments made by Molly C. Michelmore as the chair. I would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers of Social Science History.