Introduction

Social scientists and historians invest talk with considerable significance. In their more revelatory moments, what people say speaks volumes about their beliefs, values, and experiences (and thereby, about the worlds they occupy), and even when talk is prosaic or formulaic, it can evince relationships of power, amity, and antagonism (e.g., Cohen Reference Cohen1998).

The advent of inexpensive audio recording technology has ensured a great deal of raw data on talk, allowing for the flowering of the overlapping subfields of sociolinguistics, discourse analysis, and conversation analysis (e.g., Tannen et al. Reference Tannen, Hamilton and Schiffrin2015). Historians of the twentieth century have sometimes benefitted from audio recordings as well, such as those secretly made of German generals held captive by the British during World War II (Neitzel Reference Neitzel2007) and those made by Saddam Hussein of meetings of his inner circle (Woods et al. Reference Woods, Palkki and Stout2011). However, scholars of earlier historical periods lack such data and, even today, only a small fraction of talk is recorded, and what is recorded does not necessarily shed light on what is not.

Memories of talk are a common substitute, when a participant either put those into writing or was later questioned. This was an important source of information in the original edition of Graham Allison’s Essence of Decision (1971), about the Cuban Missile Crisis. Published two years before it was revealed that President Kennedy had secretly tape-recorded the discussions he had with his advisers on the Executive Committee (ExComm) of the National Security Council (NSC), and thirty years before those recordings were released, the book relies on recollections, particularly memoirs by Robert Kennedy (Reference Kennedy1969) and Theodore Sorensen (Reference Sorensen1965). Another example is Diane Vaughan’s (1996: 278–333) analysis of the meeting of engineers that resulted in a green light for the final launch of the ill-fated Challenger, based on interviews and congressional testimony. A final example, from a journalist, is Bob Woodward’s Obama’s Wars (2010), about President Obama’s strategy in Afghanistan and Pakistan, based largely on interviews with people who attended White House meetings.

One problem with such recollections is that our “conversational memory” is not especially good: Experimental evidence suggests that we forget much of what was said in a matter of minutes (Stafford and Daly Reference Stafford and Daly1984). Another problem is spin. Given what we now know about the Cuban Missile Crisis, for instance, Robert Kennedy, the president’s brother and attorney general, subsequently exaggerated his importance as an advocate for the temperate approach that brought the crisis to a peaceful resolution (Kennedy Reference Kennedy1969; Stern Reference Stern2012: 37). And Vaughan (Reference Vaughan1996: 280–81) warns that the people questioned about the Challenger disaster may have distorted the truth to protect their jobs. As for Bob Woodward, one reviewer observes that his “narratives are propelled in part by who talks to him and, just as important, who gives him the best, most detailed and colorful descriptions of what went on in all those secret meetings” (Karl Reference Karl2006), which implies a bias in favor of whoever can tell the best story, however partial.

In between recordings and memories are accounts produced in situ, while the meeting (or more generally, encounter) was in progress, without the aid of audio recording technology; often these are referred to as “minutes,” particularly when they serve as the official record. Such accounts are especially interesting when they purport to represent not only who was present and what was decided (which is the extent of some minutes, especially in the corporate world) but also who said what and in what order. Historian Carlo Ginzburg (Reference Ginzburg1982) made famous use of court transcripts from the 1584 and 1599 trials of a miller brought before the Roman Inquisition on charges of heresy, in his attempt to reconstruct the defendant’s worldview and the sources from which it was cobbled together. And Anderson (Reference Anderson1983), writing more than a decade after Allison (Reference Allison1971), relied on ExComm minutes and meeting notes in his own work on the Cuban Missile Crisis—records that were unavailable to Allison, though they were to be superseded by the secret recordings. More recent examples include Ermakoff’s (2015) study of minutes (supplemented by ex post accounts) from the history-changing meeting of the French National Assembly on August 4, 1789; Graber’s (2007) study of the official records of meetings of civil engineers in France at the turn of the nineteenth century; Gibson’s (2018) use of Politburo meeting minutes from Communist Poland and China in his study of state deliberations about the imposition of martial law; and Abend’s (2013) use of faculty minutes in his study of the origins of the field of business ethics. Not surprisingly, minutes are a regular go-to primary source for organizational scholars (e.g., Gioia et al. Reference Gioia, Price, Hamilton and Thomas2010; Golden-Biddle and Rao Reference Golden-Biddle and Rao1997; Schwartz-Ziv and Weisbach Reference Schwartz-Ziv and Weisbach2013; Tuggle et al. Reference Tuggle, Schnatterly and Johnson2010), especially organizational historians (Rowlinson et al. Reference Rowlinson, Hassard and Decker2014); Chandler (Reference Chandler1962) is a well-known example.

Scholars who use such data naturally want to believe in their fidelity to the spoken word. Anderson, for one, describes the ExComm minutes as “essentially transcripts of the meetings” (1983: 203). Ginzburg is even more optimistic. Writing of the transcripts from the Roman Inquisition, he claims that “not only words, but gestures, sudden reactions like blushing, even silences, were recorded with punctilious accuracy by the notaries of the Holy Office. To the deeply suspicious inquisitors, every small clue could provide a breakthrough to the truth” (Ginzburg Reference Ginzburg1989: 145; see also Cohen Reference Cohen2012). Historian John Jeffries Martin, however, has a different view. Apropos of the same transcripts, he writes that “the goal … was not to record every word but rather every pertinent word and to create a document that would play an instrumental role in the resolution of the case” (2011: 380). The notary’s task, in other words, was to create an organizationally useful document, not a perfect record that would meet the sanguine expectations of historians centuries afterward.

It is easy to suspect that modern minute-takers are equally selective. It is hard to take down every word, especially when talk is animated and several people are competing to speak—a situation that would tax even a properly trained and equipped stenographer. Faced with the need to be selective, a competent minute-taker will naturally prioritize content that they think subsequent consumers of their minutes will care about. Compounding this, minutes may be altered after the fact, prior to their finalization, whether by the minute-taker or someone else. This happened during the early years of the Soviet Union, when Politburo members were given the opportunity to alter the stenogramma of a meeting before it was disseminated (Gregory Reference Gregory, Gregory and Naimark2008; Lovell Reference Lovell2015), and the practice continues in many organizational settings to this day. We might say that minutes are not merely taken, but actively made, and that minute-takers are equally minute-makers, sometimes with input from others.

The only way to gauge the fidelity of such records is to compare them with an audio or video recording of the very same event. But such a comparison is rarely possible, both because recording technology was not available in sixteenth-century Italy or eighteenth-century France (and too rudimentary to be useful in 1920s Russia) and because, nowadays, recordings reduce the need for minutes and vice versa.

There have been some exceptions. One is Slembrouck’s (1992) comparison of the official minutes of British parliamentary proceedings, taken in shorthand by reporters working 5-to-10 minute shifts, with audio recordings of the same. Slembrouck observes that the minutes omit disfluencies such as partial words and incomplete utterances; correct informal language (such as contractions and lapses in proper forms of address) and grammatical mistakes; rearrange words so that sentences are more fluent; omit hedges like “I think”; and rearrange overlapping talk into consecutive speaking turns while omitting failed attempts to hold the floor. Another is Bucholtz’s (2000) comparison of a police transcript of an interrogation with the audio recording. She found that the official transcript omits much of the effort the police officer made to strike a deal with the defendant, in an effort to get him to talk, mainly by declaring some of the key utterances “unintelligible.” A third is Stark’s (2012) comparison of Institutional Review Board meeting minutes and audio recordings. She describes how such minutes create the fiction of a unified committee by downplaying internal disagreement.

The present study is based on comparisons of this kind, though the analysis is more intensive and the implications more far-reaching. Several US presidents secretly tape-recorded White House meetings and phone calls, particularly John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Richard Nixon. The recordings President Kennedy made of the meetings of his advisers on the ExComm have garnered special attention for the light they shed on decision making during the Cuban Missile Crisis in the fall of 1962 (e.g., Allison and Zelikow Reference Allison and Zelikow1999; Fursenko and Naftali Reference Fursenko and Naftali1997; Gibson Reference Gibson2012; Stern Reference Stern2003). Many of these meetings, and others of the National Security Council (NSC) during Kennedy’s presidency, were also attended by NSC Executive Secretary Bromley K. Smith, who took notes, later typed up into formal minutes, without knowing that a tape recorder was rolling. Other meeting participants also took minutes, of a sort—especially, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy (who oversaw the NSC for Kennedy) and Director of Central Intelligence John McCone. From Nixon’s administration, too, we have NSC minutes created by staff members who were similarly ignorant of the tape recorder, though we only have recordings for a few of those meetings.Footnote 1 Many of these meeting minutes were subsequently included in Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS), a compendium of government documents assembled by State Department historians, available online,Footnote 2 while the audio recordings can be accessed through the web sites of the Presidential Recordings Project of the Miller Center at the University of VirginiaFootnote 3 and the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library.Footnote 4

The NSC data are especially interesting because unlike parliamentary proceedings (Slembrouck Reference Slembrouck1992), congressional hearings (Molotch and Boden Reference Molotch and Boden1985; Neisser Reference Neisser1981), courtroom interaction (Matoesian Reference Matoesian1997), and police interrogations (Bucholtz Reference Bucholtz2000; Coulthard Reference Coulthard, Caldas-Couldhard and Coulthard1996), where turn-taking is very orderly and speakers are expected to speak clearly for the benefit of the audience, stenographer, or tape recorder, these four meetings, at least, involved a great deal of unstructured interaction replete with overlapping talk, simultaneous conversations, mumbled comments, restarted and abandoned sentences, and so on. This was not, in other words, talk structured by the institution to make the record-keeper’s job an easy one, making the use of discretion unavoidable.

My goal is not merely to assess the fidelity of the notes and minutes, but, more interestingly, to identify the procedures used to convert talk, with all of its complexities, disfluencies, ambiguities, and occasional disarray, into a written record of who said what. The research is guided by the principles of ethnomethodology, which is the study of the mundane practices used by people to ensure social order as an ongoing, collaborative effort. In organizational settings, ethnomethodologists have studied the practices used by people to perform official tasks such as creating records (Berg Reference Berg1996; Garfinkel Reference Garfinkel1967: 186–207; Lynch Reference Lynch2009; Meehan Reference Meehan1986), when the formal rules are either impossible to follow or fail to exhaustively spell out what should and should not be included. An offshoot of ethnomethodology is conversation analysis, which focuses on the sequential production of talk both in ordinary conversation and in institutional settings such as the doctor’s office and the courtroom (Goodwin and Heritage Reference Goodwin and Heritage1990). Combining the broad ethnomethodological program with conversation analysis specifically, this research is about how conversation is represented as an organizational record, presumably for organizational purposes.

While ethnomethodologists have not studied minutes as such, those have a counterpart in ordinary conversation that has been studied: restatements of recent talk, as announced by expressions such as “so what you’re saying is” and “in other words.” Following Garfinkel and Sacks (Reference Garfinkel, Sacks, McKinney and Tiryakian1970), Heritage and Watson (Reference Heritage, Watson and Psathas1979) call these “formulations,” and show that formulations entail some combination of (1) the preservation of portions of the earlier talk being formulated, such as specific facts; (2) the deletion of many details considered incidental; and (3) transformation, which substantively restates earlier talk through paraphrasing—with the implication that transformation may be consistent with preservation inasmuch as the paraphrase is accurate. Minute-takers surely do these things as well, though with greater latitude to change the “gist” of what was said as the originator of the minuted talk is not immediately afforded the opportunity to challenge the formulation. Also, to Heritage and Watson’s list of practices I will add another: the addition of content, or putting into someone’s mouth words they did not say—sometimes, but not always, for the purpose of disambiguation.

Background: The National Security Council

The National Security Council was created by the National Security Act of July 26, 1947, to “advise the President with respect to the integration of domestic, foreign, and military policies relating to the national security” (qtd. in Rothkopf Reference Rothkopf2005: 5). In practice, presidents have used, or failed to use, the NSC according to their predilections, and in response to the challenges they respectively faced. Truman avoided dealing with it during its first three years, seeking guidance from personal advisers instead, but the council assumed greater importance starting in 1949, with the formation of NATO and the growing Soviet threat, followed by the start of the Korean War. Eisenhower invested it with even more importance as the preeminent body for deliberating foreign policy proposals, and then implementing those he approved. This resulted in an imposing (military-inspired) bureaucracy that critics saw as overly rigid, and too consumed with minor issues to anticipate and manage crises. Kennedy internalized this critique and sought a more intimate NSC, putting it under the charge of National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, who slashed the staff. (Bromley Smith, who had previously held a prominent position on Eisenhower’s NSC, later spoke of his role in trying to repair the damage after he was recruited by Bundy [Smith Reference Smith1969].) This smaller body was arguably a liability in the weeks leading up to the Bay of Pigs, but served Kennedy better in the form of the ExComm, which roped in additional advisors as needed (Rothkopf Reference Rothkopf2005: 85). President Johnson diminished the NSC further, preferring his much more informal Tuesday Lunch Group. Finally, Nixon (with whom this cursory history concludes) sought to reinvest the council with the importance it enjoyed under Eisenhower, placing it under the control of National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, who rebuilt it and used it as a base of operations from which to establish his authority over foreign policy, at the expense of the State Department and its secretary, William Rogers (Henderson Reference Henderson1988: 123–38).Footnote 5

This article focuses on four NSC meetings, three under Kennedy and one under Nixon. The first two are considered together, as Bromley Smith took minutes for both. One is the 5:00 p.m. meeting of the ExComm on October 25, 1962, the first for which we have minutes that we can safely attribute to Smith—his name is at the bottom—following the discovery of the Soviet missiles in Cuba on the fifteenth.Footnote 6 The president, who controlled the tape recorder, arrived at the meeting late and only about 19 minutes were recorded. The topic of discussion was the naval blockade the United States had imposed on the island in response, and more particularly whether to intercept two ships that were within reach of the navy: the East German passenger ship Völkerfreundschaft and the Soviet tanker Bucharest.

The second is the 6:00 p.m. meeting of the NSC on October 2, 1963—almost a year later.Footnote 7 This lasted about 28 minutes and was recorded in its entirety. The meeting took place at a sensitive moment in the Vietnam War: The United States had briefly (and secretly) supported a coup against South Vietnamese President Diem, with whom it had become disillusioned, partly because of Diem’s violent crackdown on Buddhist monks the previous May. However, at the time of the meeting Kennedy had decided to try to sway Diem using political pressure, including the threat of a suspension in aid (Hammer Reference Hammer1987). (A coup later happened anyway, with tepid support from the United States.) The main topic of conversation during the meeting was a planned press release about US policy, occasioned by a new report by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Maxwell Taylor (which offered a grim assessment of Diem but recommended continued political pressure on him rather than active support of a coup), but more immediately necessitated by the need to address publicly aired differences between the State Department, which wanted Diem removed, and the military and CIA, which opposed this.

The reason for considering this second meeting is that it affords us a unique advantage that will also help with our interpretation of the minutes from the earlier one: Bromley Smith’s handwritten notes, on the basis of which the final minutes were subsequently constructed, were discovered in the London B. Johnson Presidential Library, where Smith’s papers are housed.Footnote 8 These notes (three pages in all) provide clues about the crucial intervening step between the original talk and the final, polished minutes, and vividly capture the embodied nature of minute-taking back when this meant writing with pen and paper: some words are crossed out, others squeezed in, and sudden changes in the slant of words may indicate edits made from a slightly different angle sometime later.

While Smith took minutes for many NSC meetings under President Kennedy, and many of those were also tape-recorded, I concentrate on these two meetings on the grounds that there is more to be learned from a finely textured analysis of two cases than a more superficial analysis of a larger number, which invites cherry-picking and the neglect of puzzling details that may also be the most revealing. However, it is possible, and indeed likely, that Smith’s minute-taking practices in these meetings were idiosyncratic, his personal and improvised solutions to the generic challenge of creating a written record of talk witnessed in real time.

For the sake of comparison, then, I undertake two supplemental analyses. The first is of the 10:00 a.m. meeting of October 23, 1962, again from the Cuban Missile Crisis. Forty-six minutes of the meeting were recorded, excluding an intelligence update at the beginning (excised for reasons of national security) and an interruption partway through when Kennedy turned off the recorder during a discussion of communication challenges in Latin America. Smith did not take minutes, but two meeting participants did: CIA Director John McCone and National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy.Footnote 9 At this meeting the ExComm discussed photographs of the missiles, reasons that they were not detected earlier, when the blockade (or “quarantine”) would go into effect, possible responses to an anticipated attack on US aircraft by surface-to-air missiles in Cuba, obstacles to requisitioning commercial ships in preparation for an invasion of the island, the extension of military tours, and additional surveillance flights for the sake of even better photographs to convince the public of the threat.

The second supplemental case is the February 26, 1971, 11:45 a.m. NSC meeting, when Richard Nixon was president and someone else—the minutes are unattributed, but we know it was not Bromley Smith, as he was no longer on the NSC staff—was taking minutes. About an hour and 20 minutes of the meeting was recorded, though the recording begins well after the meeting was underway (judging from the minutes). Two matters were discussed. First was the progress of the war in Vietnam, and Nixon’s simultaneous domestic struggles with a Democratic-controlled Congress and a largely skeptical media. The second was the possibility of a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt, the prospects for which were undercut by Israel’s refusal to consider withdrawing to its pre-1967 borders. Secretary of State William Rogers, thoroughly exasperated with this rigidity, felt that the United States should compel Israel to negotiate. During the meeting, Nixon appeared to agree, but had apparently been persuaded by Henry Kissinger, then National Security Adviser, to stand by Israel regardless, on the grounds that the US–Israel alliance was indispensable in the competition with the Soviet Union for influence in the Middle East (Yaqub Reference Yaqub and Ashton2007). (The minutes list Kissinger as present. According to the minutes, he spoke a few times, but before the tape recorder was turned on, after which he was never heard to speak. As talkative as he was otherwise, he may have left.)

We will see that the cases present us with different models of minute-taking. A first hint of this is the amount of detail in the minutes, controlling for the amount of talk in the corresponding recording. For every 100 words heard in the audio, Bundy and McCone wrote approximately six or eight in their minutes, respectively. Smith, in contrast, wrote between 24 and 25, while Nixon’s minute-taker wrote about 32—a number that jumps to 42 if we exclude the 20-minute presentation by Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, which the minute-taker mostly ignored.Footnote 10

Another difference is in format. Bromley Smith’s minutes (labeled “summary records” in the FRUS archive) were written in narrative format, from the perspective of a passive observer and replete with speech act (Austin Reference Austin1962) glosses that, to some degree, reflect Smith’s interpretation of events: “Mr. McCone noted,” “Secretary McNamara reported,” “Secretary Rusk called attention,” “the President decided.” Though briefer, Bundy and McCone’s minutes read similarly. In contrast, of the 25 Nixon-era meetings for which minutes are available, all but three are formatted like scripts, with a speaker’s name followed by a colon followed by the talk attributed to him; this includes use of the first-person “I.” That is true for the three meetings for which I have been able to obtain audio, and the format gives the impression of a highly accurate and detailed account meant to resemble a transcript of an audio recording.

Further investigation revealed that the narrative format was consistently used for NSC meetings from their beginning under Truman through Kennedy’s administration, but was gradually supplanted by the transcript format (with some movement back and forth) under Johnson (starting in 1966), until it had become standard by the time Nixon took office. That remained the norm under Ford. NSC minutes under Carter were a mix of the two formats, sometimes switching within a single meeting. Minutes under Reagan (the last president for whom they are available) also alternated.

What purpose, or purposes, did the assorted minute-takers have in mind? Who were their intended audiences and to what use did they imagine the minutes would be put? To a large extent, the impulse to keep an accurate record was part of the organizational culture of the time. In addition, Bromley Smith, Nixon’s minute-taker, and Bundy (who frequently took minutes when Smith did not) likely had in mind several audiences. The first was meeting participants, who would sometimes review the minutes as they reflected on the difficult decisions in which they were involved. The second was subordinates of those in the meeting, to whom the minutes could be made available if this was deemed useful for their work, assuming they had the necessary security clearance (often, “top secret”). Officials from other parts of the government could also be provided with the minutes, again assuming the proper security clearance and the perception of a valid interest.Footnote 11 McCone, who also frequently took his own minutes, may have done so to have a record of what the meeting entailed for him, and the CIA, specifically.

Method

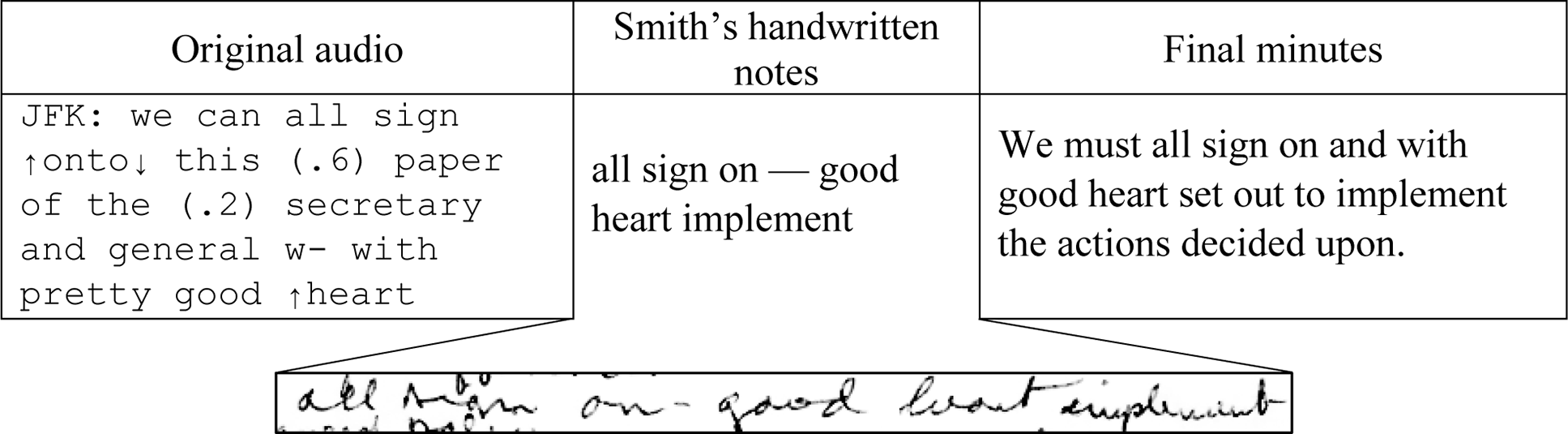

The analysis involved the careful comparison of the audio recordings with the final minutes (hereafter, “minutes”) and, when they were available, Smith’s handwritten notes (hereafter, “notes”). The first step was to create verbatim transcripts of the audio, including restarted words, filler words (like “uh”), laughter, side conversations, and overlapping talk.Footnote 12 The second step was to match each remark in the minutes with the corresponding segment of the transcribed audio. The directionality of this procedure was deliberate, anticipating that much of what was said would have no counterpart in the minutes. Figure 1 illustrates. The group had been talking about the East German passenger ship Völkerfreundschaft. In the audio, represented on the left, Bundy suggests that UN Secretary-General U Thant’s request that the United States not intercept any Soviet ship had no bearing on one from East Germany. On the right, the minutes paraphrase this observation, with “this ship” becoming “the East German ship,” while the overt reference to Soviet ships is dropped.

Figure 1. Corresponding segments from the transcribed audio and final minutes, October 25, 1962 meeting (tape 38.2, 1:59).

This procedure was adapted as needed to accommodate the data available for each meeting. Figure 2 illustrates for the October 2, 1963 meeting, for which we have Bromley Smith’s handwritten notes. On the left is a transcription of the segment of audio most directly reflected in the line of notes in the center, an image of which is at the bottom. On the right are the lines from the minutes corresponding to those same lines from the notes. In this case I began with the line in the notes, and then found the corresponding lines in the minutes and segment of the audio, mindful of the fact that both the audio and the minutes would likely include additional content given how spare the notes are. The analysis of the October 23, 1962 meeting also involved a three-way comparison, between the transcribed audio, Bundy’s minutes, and McCone’s minutes.

Figure 2. Corresponding segments from the transcribed audio, handwritten notes, and final minutes, October 2, 1963 meeting (tape 114.a49, 1:49).

This matching procedure was greatly facilitated by the preservation of temporal order by all the minute-takers: while none noted everything that was said, what they did put in the minutes was almost always in the same order as in the audio, and on the rare occasion that the minutes reorganized talk, that shuffling was very localized. That said, lest the presumption of temporal preservation bias my own conclusions, before declaring that a remark in the audio was omitted from the minutes I was careful to search the entirety of the latter; conversely, before declaring that the minutes included something missing from the audio I was careful to scrutinize my own transcript from start to finish.

Candidate excerpts selected for inclusion here were subject to further refinement using the transcribing conventions of conversation analysis (see the supplementary appendix), which offers the best way to represent conversational minutia—such as pauses, overlapping talk, and changes in volume or pitch—that may be interactionally telling or consequential though they are typically omitted from published reports. That is, this provides the best way of representing what “really happened” in print. That said, I omit this notation when quoting in the text, and in both the excerpts and text I employ standard rather than phonetic spelling for the sake of readability.

Analysis

Minutes under Kennedy: Bromley K. Smith

Bromley Smith’s role was to document what happened in the meetings of October 25, 1962, and October 2, 1963, at least partly for the benefit of people not present. Yet his final minutes were much more succinct than the original conversation. This suggests significant feats of both preservation and deletion, but sometimes content was also added. I consider each operation in turn, before considering how subtler changes in meaning were occasioned by Smith’s precise minute-making habits.

Preservation

There is, not surprisingly, more than a passing resemblance between the final minutes and the audio recordings: While much of what is in the audio did not find its way into the minutes, it is not hard to associate sentences in the latter with remarks in the former. Figure 1 provides one example, involving a typical combination of close paraphrasing and the preservation of particular words (here, “cover”), and of course the use of the third person, in accordance with Smith’s narrative format. For another, a little more than a half an hour into the Cuba meeting, Secretary of State Dean Rusk said, “wouldn’t you really step back and look at it for a second, based on any real suspicious information that we have, the block- the quarantine is now fully effective.” The final minutes dutifully report, “Secretary Rusk noted that the quarantine had become fully effective.”

Other turns of phrase were even more memorable, and we see how Smith worked to preserve them. For example, refer back to figure 2. In the recording, Kennedy observes that everyone can concur with the McNamara–Taylor report on the situation in Vietnam “with pretty good heart.” While introducing other changes I will discuss, the “good heart” comment was too good to leave out, and it survived to the minutes. Also preserved was the president’s characterization of any statement denying the internal differences as “fluffy.”

Deletion

If we take Smith’s task as one principally of preservation, it is acts of deletion, or omission, that are most telling, as the pruning that gave the final minutes their shape. Indeed, it is hard to separate the two operations, as something was preserved when it was not deleted, and conversely. Importantly, everything that was in the notes (from the Vietnam meeting) found its way into the minutes, which means that the moment of deletion was when Smith was sitting in the room, making these decisions on the fly. Many of these omissions are straightforward consequences of the fact that Smith was not attempting to create a verbatim record, but rather a narrative, third-person summary of the “gist” (Heritage and Watson Reference Heritage, Watson and Psathas1979). First, and not surprisingly, Smith was not concerned with conversational minutia such as overlapping talk or disfluencies like instances of um or uh, pauses, and restarted (or abandoned) words and sentences. For example, in an example given earlier, Rusk started to refer to the “blockade” (“block-”) and then replaced this with “quarantine”—the preferred term given that a blockade was illegal under international law absent a formal declaration of war; Smith made no note of the aborted label. Second, Smith omitted the connective tissue whereby a speaker signaled how his remark related to the one that preceded it, particularly turn-initial discourse markers such as well and oh which convey things like disagreement and surprise (Gibson Reference Gibson2010; Heritage Reference Heritage1984; Schiffrin Reference Schiffrin1987), and also short expressions of agreement, such as all right, so that we mainly know a person’s position inasmuch as they independently articulated it. Third, other short remarks were also often ignored, even if they communicated an independent, nonredundant point. For example, during the Cuba meeting, Secretary of the Treasury Douglas Dillon suggested that nighttime reconnaissance of the missile sites “would show you whether they were working secretly.” This was arguably a substantive contribution but Smith made no note of it. Fourth, Smith sought firm statements while disregarding hedges and qualifiers; recall how “wouldn’t you really step back and look at it for a second, based on any real suspicious information that we have, the block- the quarantine is now fully effective” was reduced to “Secretary Rusk noted that the quarantine had become fully effective.”

Most of this points to an understandable preference for substance over delivery. However, Smith’s omissions targeted specific kinds of content. For instance, he was systematically disinterested in reproducing operational details, such as the particulars of ship movements and surveillance during the Cuba meeting, as well as most talk about the exact wording of the public statement that the group worked on during the Vietnam meeting. Also in the Vietnam meeting, Smith omitted some frank remarks about the need to minimize public manifestations of internal disagreement. For one example, Kennedy urged the group to overcome its differences and support a single policy, which was reflected in the minutes, and then added, “we ought to do a little window dressing and atmosphere changing of our own,” which was not. In place of that, the notes read “agreed policy/get all aboard,” and the minutes say “we must get ahead by carrying out the agreed policy.” Thus, while Smith documented the concern with internal divisions, he out left the remarks most appropriate to the “backstage” (Goffman Reference Goffman1959) about the need to manage outward appearances.

We might, then, hypothesize that Smith favored talk pertaining to major decisions. Yet his omissions went further still. A main topic of the Cuba meeting was whether the president should order the US Navy to intercept the Völkerfreundschaft—the East German passenger ship thought to be transporting Soviet technicians. Kennedy repeatedly opined that this was a bad idea, principally because UN Secretary-General U Thant was trying to mediate and had asked that there be no confrontation until Khrushchev responded to his request that Soviet ships be diverted away from Cuba (recall figure 1). This rationale was duly noted in the minutes each time. There was an additional reason not to intercept the ship, however: The navy might have had to fire upon it had it refused to stop, to disable it, and in the process might have seriously damaged or sunk it, threatening its estimated 1,500 passengers. McNamara alluded to those 1,500 in the opening minutes of the recording and later more explicitly warned of “the loss of life under circumstances that would indicate that we’d acted irresponsibly.” Sometime later Attorney General Robert Kennedy referred to “Bob’s [McNamara’s] point about the fact that it has got fifteen hundred people on it,” and then Rusk, too, worried that they would “sink it or anything of that sort with fifteen hundred people.” Soon after that, the president joined in: “you try to disable it you’re apt to sink it.” Yet though the fact of McNamara, Rusk, and President Kennedy’s opposition to intercepting the ship comes through clearly enough, this specific concern appears only once in the minutes, as a warning from McNamara about “the great danger to the some 1500 passengers aboard” that was expressed before the president arrived and turned on the recorder. Thus, the minutes understate the extent to which this was a concern, particularly of the president. Perhaps Smith thought that one reference to this concern in the minutes, wherever it was located and whomever it as attributed to, was enough.

On the other side, there were some in the room who pushed back on the president’s reluctance to intercept the Völkerfreundschaft. A few minutes into the recording, presidential aide Theodore Sorensen suggested stopping it as a way to demonstrate US resolve that did “not engage the prestige of the Soviets directly.” Sometime later Dillon warned about providing “evidence to the Bloc that you’re not stopping” ships. A few minutes after that, Rusk suggested that the blockade could be viewed as fully effective given that no Soviet ship had yet challenged it, to which Bundy responded, “but I don’t think that can be said about the East German ship which went through Leningrad and picked up a lot of cargo”—with the implication, again, that it should be stopped. A bit later, Sorensen explicitly suggested stopping the ship: “what about the combination, Bobby, of letting the Grozny [a Soviet tanker] off, go through, and stopping the East German ship?” Even President Kennedy saw the point of stopping the ship: “the only reason for picking this ship up is we’ve got to prove sooner or later that the blockade [is effective].” Remarkably, every instance of an argument in favor of intercepting the Völkerfreundschaft was omitted from the minutes, suggesting that this indecisiveness was judged a liability.

Addition

When Smith put words into someone’s mouth, usually it was to make explicit something that was implied but that those in the room would have immediately understood. One example is in figure 1, where Smith identified the ship alluded to by Bundy. Another is when, during the Vietnam meeting, President Kennedy said: “there’s no disagreement back here, there’s no disagreement between us and Ambassador Lodge,” and Smith disambiguated “back here” in his notes: “among State Def[ence] and CIA.” This addition was preserved in the final minutes. Sometimes clarifying material was added only at the final stage, such as when, in the minutes, Smith had Kennedy explain exactly what line in the public statement draft he considered “fluffy” (one that denied disagreement between US agencies), based on a reasonable guess from the context in which the president voiced this complaint.

Usually the content added seems reasonable enough, and might be considered mere paraphrasing, but sometimes Smith appears to have hazarded guesses as to what was intended, as if the reduction of ambiguity was a goal unto itself. In the remark in figure 2, for instance, Smith apparently judged “sign on” too vague and added, in his notes, the word “implement” (which then demanded an object, discussed shortly). In another instance, during the 1963 meeting, Kennedy anticipated that his Vietnam policy would be criticized on “moral” grounds. The next to speak was Under Secretary of State George Ball. Ball cautioned that they had “more than one audience,” that at the United Nations “this is going to be examined with great attention,” and that, as a consequence, “we shouldn’t indicate that our only interest is in winning the war.” What the other “interest” might be, he did not say, but Smith’s handwritten notes purport to know: “Ball — Rusk wants stress on moral for UN effect.” Of course, Smith might be right that his is what Ball had in mind, but it is a nontrivial bit of guesswork, and the “moral” descriptor appears to have been borrowed from the president’s prior speaking turn. Furthermore, it was not Ball, but Bundy, who invoked Rusk, but it seems Smith assumed that Ball was speaking on his superior’s behalf. The final minutes are true to the notes: “Mr. Ball said that he and Secretary Rusk felt that there should be stress on the moral issues involved because of the beneficial effect which such emphasis produced in world public opinion, especially among UN delegates.”

Even more surprising than the addition of clarifying material and disambiguation are occasions when Smith, perhaps at the later behest of someone in the meeting, attributed to people assertions that they did not make. To take the starkest example, at one point Bundy fretted that the US ambassador to South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., would object to the statement the council was drafting—Lodge was adamant that Diem had to be removed from power—anticipating that it “would bring back a rocket from the ambassador, saying, oh how could you miss my whole point?” In response, President Kennedy asked, “It’s all right, isn’t it?” and someone, possibly Ball, mumbled something brief, and the matter was dropped. The handwritten minutes reduce this to “Bundy — Lodge view.” But the minutes report something else: “He [Bundy] said Ambassador Lodge could be told that because of the time pressure it had not been possible to clear the statement with him, but that it was felt here it would meet his requirements.” Perhaps Bundy, on reviewing the minutes, requested the change so that Lodge would not feel entirely neglected. He certainly cannot be heard to make such a suggestion in the recording.

Skeletal grammar and its consequences

Thus far, I have concentrated on instances where entire substantive assertions were present in the audio but missing from the minutes, or vice versa, in addition to the wholesale disregard for conversational minutia. But many of the changes effected in the minutes occurred at a more fine-grained level, as individual words were added, swapped, and deleted, and for reasons we can reconstruct from a more careful examination of Smith’s handwritten notes from the Vietnam meeting.

When talk in the audio has a clear counterpart in the final minutes, it can also be found in the notes. Indeed, with very few exceptions, it seems as if Smith based his minutes on the notes without supplementing these with any independent memory of the events. This opened the way for some subtle, and some not-so-subtle, alterations in meaning because when taking those notes Smith employed a sort of skeletal grammar that omitted information that then had to be conjured up when they were reconstituted into the final minutes, or simply left out.

Certain grammatical categories were especially vulnerable to omission, including arguments—subjects and objects. For example, at the beginning of the Vietnam meeting, President Kennedy said, hopefully, “I think most of us really are in agreement now.” In his handwritten notes, Smith omitted “us,” which in this construction is the subject, and simply wrote “most in agreement.” Consequently, a subject had to be invented when the final minutes were reconstituted, and Smith opted for “officials involved”: “Most of the officials involved are in agreement”—which arguably extended the circle of alleged consensus well beyond the men in the room.

Closely related to verb arguments are adjuncts; indeed, some linguists doubt that we should distinguish between the two (Tutunjian and Boland Reference Tutunjian and Boland2008). Often taking the form of prepositional phrases, these, too, were sometimes omitted in the notes, inviting their later substitution. In one instance this meant substituting something vague with something more concrete. Worried about leaks, Kennedy said: “you ought to hold back very hard” and then went on to repeatedly urge the group not to “discuss” any actions the United States might take “with anybody” and “outside this room.” Sitting in the room, Smith wrote “JFK — Hold back — not talk.” This omitted mention of any particular outside party with whom not to talk, even the original “anybody,” and in the final minutes Smith strove to fill this hole with a new, more precise prepositional phrase: “The President directed that no one discuss with the press any measures which he may decide to undertake on the basis of the recommendations to be made to him.” (All italics were added throughout this article.)

Another example, in figure 2, illustrates the interplay of the sacrificeability of arguments/adjuncts and the urge to disambiguate. President Kennedy said: “we can all sign onto this paper of the secretary and general,” but in his notes Smith omitted “to this paper.” At the same time, he added, by way of disambiguation (I earlier suggested), the word “implement.” This is a transitive verb requiring an object, and in the minutes Smith chose something other than McNamara and Taylor’s report—“the actions decided upon,” which presumably referred to (or could be read as referring to) decisions made during this very meeting. (Smith’s notes also omit the subject “we,” but this was restored in the minutes.)

In his notes, Smith also often omitted modal verbs like must, can, and should, which opened the way to their later manufacture. Thus, returning yet again to figure 2, “we can all sign on to this paper” in the audio became “all sign on” in the notes and then “We must all sign on” in the minutes. And again, McNamara’s promise that “we could come back Friday” (with recommendations) was rendered as “come back Friday with recommendation” in the notes and “The group would return to the President by Friday with specific recommendations” in the minutes. In another instance, the modal verb was added where none originally existed: McNamara said of Agency for International Development administrator David Bell that “he’s not prepared to make any statement,” which turned into “Bell to say nothing” in the notes, and “Bell should say nothing” in the minutes. And on another occasion the modal verb simply vanished: Early in the meeting President Kennedy said, “we ought to appear to be pretty general agreement,” which was simplified as “agreement” in the notes, and then reconstituted as “we are agreed” in the minutes. Most and perhaps all these arguably nudged the NSC’s portrayal, in the minutes, in the direction of greater decisiveness and assertiveness. This points to another way in which Smith’s commitment to a particular public image may have informed his minute-making decisions, though more data are needed to confirm this.

Smith’s note-taking practices may explain two instances of apparent misattribution in the Cuba meeting, when someone was credited with a proposition that was not (or not yet) their own. Both instances stemmed from a somewhat rambling plan laid out by Robert Kennedy, which included letting both the Völkerfreundschaft and the Bucharest through the blockade line, and then announcing that no further tankers would be permitted through. This, he said, would give the president more time to decide what to do, as a confrontation at sea would be postponed, and the attorney general further suggested that ultimately it might be better to simply bomb the missile sites than stop any ships.

The minutes faithfully summarize the attorney general’s position, but then give the impression that he had allies in Dillon and, more importantly, the president, whereas in actuality they were merely restating his position. First, after Robert Kennedy had spoken for a while, Dillon interrupted to identify the “basic logic” of the plan (and the proposed strike on the island): “to have the confrontation in Cuba.” While this is arguably an attempt at formulating someone else’s idea (Heritage and Watson Reference Heritage and Watson1980), the minutes unequivocally attribute it to Dillon personally: “Secretary Dillon said he preferred that the confrontation take place in Cuba rather than on the high seas.” One can imagine the line in the notes that made this misattribution possible: “Dillon — confrontation in Cuba not at sea.”

A few minutes later the president made his own attempt at formulating some part of his brother’s plan, starting with, “well then if we followed your uh point, Bobby, we’d let the East German ship go on the grounds that it’s a passenger [ship], we’d announce tomorrow that the Soviet, uh, tomorrow afternoon we ought to have a Soviet response to U Thant which will affect this Grozny.” According to the minutes, however, “the President decided that we should not stop the East German ship.” Thus, once again we have a formulation attributed to the formulator as if it was his opinion, and again one imagines the lines in Smith’s notes: “JFK — not stop East German ship.” The consequence is striking: the identification of a decision—the only one “made” in this meeting—where none existed, though the president did ultimately decide to let the Völkerfreundschaft through.

Minutes under Kennedy: McCone vs. Bundy

Again, the minutes taken by Director of National Intelligence John McCone and National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy were even more spare than those taken by Bromley Smith, possibly because, as ExComm principals, they were more confident in their ability to discern what spoken content most needed preservation, or more restrictive in their criteria. Because we have minutes from both for the meeting of October 2, 1963, we can ask exactly how each construed the import of what was being said, even as they were sometimes the ones to say it.

The two men both noted some of the topics discussed and concerns raised—for instance, Kennedy’s worry about the vulnerability of US airfields in Florida and the need for compelling evidence to present at the United Nations—though unlike Smith, they did not seek to preserve memorable phrases, even when attributing a remark to a particular individual. What they most consistently agreed about, however, was the decisions made. This is interesting as almost none of these decisions took the form of straightforward pronouncements or commands. Thus, we can ask what sort of talk was coded as a decision by these two ExComm members (as in Huisman Reference Huisman2001), as an act of interpretation and transformation with consequences for anyone charged with putting those decisions into effect.

There were five such decisions (excluding those that merely involved delegating tasks): to begin enforcing the blockade the next morning; to extend tours of duty in the navy and marines; to immediately inform the president of any attack on a U-2 spy plane so that he could decide whether to order a retaliatory strike on the SAM (surface-to-air missile) site; to empower McNamara to make that decision in the event the president was unavailable; and to order more surveillance flights for the sake of additional photographs “to prove to a layman the existence of the missiles in Cuba,” in McNamara’s words. Interestingly, only the fourth involved a strong statement of approval by the president: “I will delegate to the Secretary of Defense on the understanding that the information would be very clear that the accident that happened was not a malfunction.” In the other cases, the idea was proposed by McNamara; no one objected; the president offered a minimal expression of support, or simply spoke as if the decision had already been made; and the sequence was interpreted as a decision. For one example, McNamara proposed announcing the blockade that evening, to go into effect the next morning. No one objected, and eventually Kennedy said “okay,” and on this basis, McCone said that “it was decided” while Bundy said that “the President approved.” For another example, consider McNamara’s request for more surveillance flights, for the sake of additional evidence of the missiles. In the audio, McNamara said that the Joint Chiefs of Staff and McCone wanted those, but the president said he doubted they were needed. After some cajoling by Bundy, Kennedy said, “well then, why don’t we do this filming thing then anyway,” and on the basis of this half-hearted endorsement both McCone and Bundy both recorded that the flights were “approved.”

On the other side, there were many things said in the meeting that neither Bundy nor McCone preserved. Not surprisingly, neither was remotely concerned with the minutia of talk, such as restarted words or overlapping talk; like Smith, their goal was not to produce a verbatim record of what speakers said, only what it amounted to. More substantively, neither took note of McNamara’s desire, which he repeated, that only a ship with offensive weapons be intercepted, for the additional evidence it would furnish. Also, neither mentioned President Kennedy’s admission that the blockade would not force the removal of the missiles already on the island, which the president indicated should be “off the record.” They also took little notice of most talk about the Organization of American States (from which the United States hoped for backing), this apparently being a diplomatic matter of little interest to either.

Next, there were many items that one man noted and the other did not. Some examples: McCone recorded more detail about who in Congress and in the press was to be contacted, presumably because he was charged with contacting them; Bundy, but not McCone, noted the president’s request for a report on the effects of a blockade on Cuba, and a similar report (suggested by Robert Kennedy) on West Berlin (anticipating that the Soviets would respond in kind); only McCone preserved evidence of a discussion of the Kimovsk, the first ship they anticipated intercepting the next morning; and only McCone noted McNamara’s reassurance that there was a plan for rescuing pilots downed at sea.

Neither Bundy nor McCone added content in the way that Smith occasionally did, such as to explicate something that was implied. However, McCone noted an “action” that had no apparent counterpart in the audio: “Action: General Taylor agreed that he would take up and confirm today CIA request that our representative be stationed with JCS planning staff and in the Flag Plot and in the JCS War Room.” Nothing can be heard in the audio about this, and Bundy reported nothing of the sort. One possibility is that Taylor and McCone worked this out during the meeting, but so quietly that it was not captured on the tape. Another is that they discussed it before or after the meeting. Either way, it seems McCone saw some advantage to recording it as it were on par with other items discussed and decided by the group as a whole.

Bundy and McCone were thus more selective in their minute-taking than was Smith in his, and often diverged, except when it came to discerning decisions. This is consistent with their different positions: Smith, charged with creating an official record for the sake of subordinates not in the room and perhaps dimly imagined future readers; and Bundy and McCone, NSC members fully caught up in the crisis in their respective roles, and presumably more concerned with items of direct of direct relevance to them than with doing their small part for the historical record.

Minutes under Nixon

Few of the minutes from Nixon’s NSC identify the person who drafted them, and none of those for which I have found recordings. Those that do have drafting information credit one of three NSC staff members: Jan M. Lodal, Wayne Smith, or W. Marshall Wright. Wayne (not Bromley) Smith is credited with the minutes for the 3:30 p.m. meeting of June 17, 1971, but what State Department historians found was his handwritten notes, which they typed up for inclusion in the FRUS archive.Footnote 13 Except for being typed, and for some omissions when a word was judged illegible, these are equivalent to Bromley Smith’s handwritten notes analyzed earlier, and shed some light on the practices used in this era to make such level of detail possible. These included abundant abbreviations (e.g., “Sov” for “Soviet” and “negs” for “negotiations”) and the omission of articles and some present tense verbs, though many modal (may, can, will, should) verbs appear.

Putting aside the question of whether Wayne Smith took minutes on February 26 as well, the ratio of words in the minutes to words in the audio of the latter meeting (between 32:100 and 42:100, depending on whether one includes the mostly unminuted presentation by Moorer) still indicates significant selectivity, so the question of how a jumble of talk was reduced to a relatively compact formal record remains, though the answers may be different given that the final product was crafted in such a way as to give the impression that nothing was omitted, as if it were a transcript.

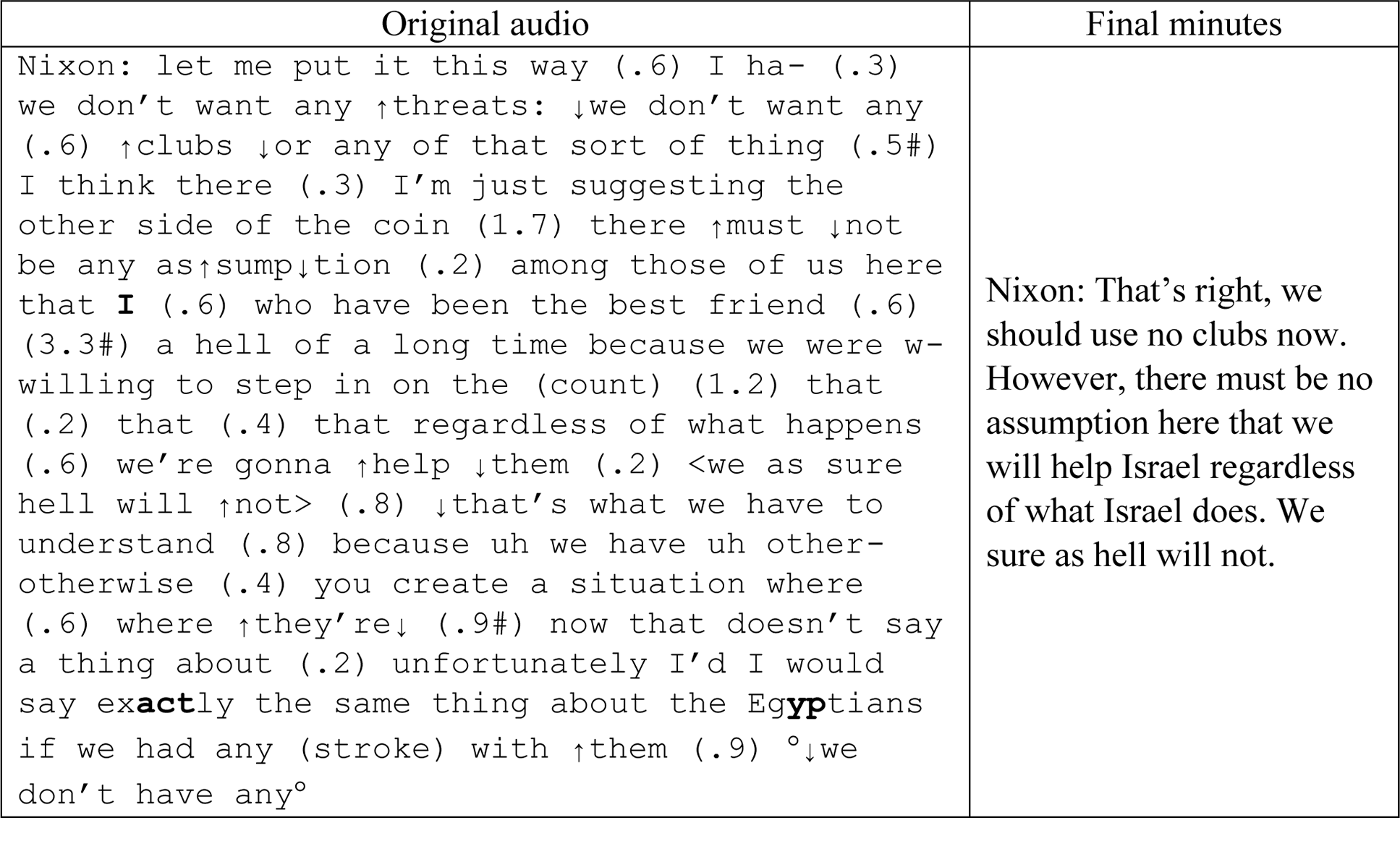

Comparing the audio and minutes for this meeting, we see significant care in representing most if not all contributions of substance, though often only in part, as if the minute-taker did not want to be faulted for ignoring those speaking turns but was content to omit much of what one contained. Most straightforwardly, words and expressions were reproduced, sometimes with quotation marks. Many factual assertions and statements of opinion were also preserved, albeit with some paraphrasing and a good deal of trimming. Figure 3 illustrates. Coming at the very end of the meeting, Nixon is purporting to agree with Rogers’s view that US support for Israel needed to be contingent on the latter’s good faith in negotiations with Egypt, though it was not Kissinger’s view and, under the latter’s sway, Nixon had repeatedly signaled that US support for the Jewish state was steadfast (Yaqub Reference Yaqub and Ashton2007). Preserved are the colorful words “clubs” and “hell,” and, with some paraphrasing, the general position (however insincere) that while the United States did not want to threaten Israel, continued support for it was contingent. Much is also omitted, however, including Nixon’s mention of being Israel’s “best friend,” his attempt at evenhandedness with regard to Egypt, and the many disfluencies Nixon produced as he struggled for the right words when speaking on a fraught topic. Also omitted is the word “threats,” perhaps because it was redundant with the more memorable “clubs.” Though not illustrated by this excerpt, this minute-taker also omitted information about overlapping talk, as well as most turn-initial discourse markers like well and now, though it is possible that the latter colored his interpretation, and paraphrasing, of whatever followed them (Tree and Schrock Reference Tree and Schrock1999).

Figure 3. Corresponding segments from the transcribed audio and final minutes, February 26, 1971 meeting (tape 48b, 1:08:05).

Other omissions bore on longer stretches of talk, suggesting systematic disinterest. In particular, the minute-taker consistently omitted details of military operations in South Vietnam during the first half of the meeting; Nixon’s attempt to draw a parallel between Vietnam and the battles of Antietam and Gettysburg during the Civil War; and his analysis of the respective levels of political bias at the three major news networks. Also ignored were several dismissive or disparaging remarks that generated laughter, such as Nixon’s reference to “one picture [in the media] of a disgruntled GI who’s had a couple of beers and [he says] Jesus Christ this is the worst battle of the war.”

When entire speaking turns were omitted from the minutes, it was usually because they were short, incomplete, or follow-up talk (such as questions and clarifications) about substantive statements that did find their way into the minutes. Ignoring most such talk spared the minute-taker from having to keep up with a good deal of chatter, but as with Bromley Smith it also means that we are denied information about who agreed with whom, as many of the shortest turns were simply expressions of agreement (for instance, by Secretary of Defense Laird in response to Rogers and Rogers in response to Nixon).

Sometimes two or more speaking turns were consolidated into one. This could mean crediting one speaker with opinions expressed by two or three, or with ideas that had been worked out collaboratively or in response to questions, as if those had not been asked. Several examples are in figure 4. The group is talking about the imminent end of an official ceasefire between Israel and Egypt along the Suez Canal, which had been in effect since the previous August. In the first and third turns, Nixon frets about the resumption of hostilities (lines 1–11) and appears to wonder who might fire first (line 13). In between, Rogers agrees that this resumption is a possibility (line 12), but this turn is not reflected in the minutes. Then Rogers expresses the view that it is not likely to be the Arabs (lines 14–16), something repeated by Joseph Sisco (lines 17–19), the assistant secretary of state and Rogers’s subordinate, but the position is attributed to Sisco alone. After some overlapping talk that may or may not have involved Nixon, Sisco makes a stronger claim, that neither side is likely to begin shooting (lines 22–23), but this is attributed to Rogers (“neither is likely”). In the final three turns (lines 24–28), Rogers, and then Sisco, and then Rogers again stress that “you never know,” a line also credited to Rogers. Added is an explanation of what “you never know” means: “Somebody might just start shooting at any time,” words put into Rogers’s mouth. Deleted is Rogers’s allusion to the Six-Day War. Thus, the minutes report three turns, by Nixon, Sisco, and Rogers, crediting each of the three main participants of this part of the discussion with some substantive contribution, but accomplish this through a great deal of collapsing and some misattribution, along with some disambiguation through addition.

Figure 4. Corresponding segments from the transcribed audio and final minutes, February 26, 1971 meeting (tape 48b, 1:02:48).

One reason these minutes have the semblance of a complete transcript is the use of deictic pronouns, like they and that, which encourage us to imagine that nothing was omitted, whatever the truth of the matter and regardless of whether the speaker actually used that word. For instance, in figure 4, the minutes credit Rogers with beginning with “neither,” a pronoun that can be read as referring to two possibilities implied by Nixon’s initial question: one side starting the shooting after the expiration of the ceasefire versus the other starting it. However, “neither” is awkward, betraying the omission of Sisco’s reference to “either side,” so that an astute reader may guess, from the minutes alone, that something was left out. But in other instances, there is no such clue.

As with Bromley Smith, to the degree that Nixon’s minute-taker put words into a speaker’s mouth that no one was heard to say, it was mainly to provide context assumed by those present, or to otherwise disambiguate. “Somebody might just start shooting at any time” (in figure 4) is an example, an effort to give precise meaning to “you never know,” or, alternatively, to replace the reference to the Six-Day War with the lesson Rogers was trying to draw from it. For another example, toward the end of the meeting, Rogers said “we have a sound place of their government of what their [Israel’s] position was prior to the time we supported the [1967 UN Security Council] resolution.” The minute-taker credited Rogers with a more expansive explanation: “Foreign Minister Eban in talking with Secretary Rusk back in 1967 said that Israel would withdraw to the old international border and did not seek territory from Egypt if the UAR would commit itself to make peace with security.”

On occasion, the minute-taker seems to have taken a leap in trying to make sense of what he heard, something we saw Bromley Smith do. The most striking instance is when, well into the second half of the meeting, Sisco predicted that Israel “will reiterate what they have said over the last three years, namely that they are willing to negotiate on the so-called question of secure and recognized borders. They will then say the sixty-seven borders are barred as a general statement and we’re ready to negotiate.” In the minutes, the Israeli position makes more sense: “Israel will probably welcome the UAR move, say it is ready to negotiate, perhaps even suggest negotiation on subjects other than borders and state that it will not return to the pre-1967 borders.” Sisco’s point, however, was that the Israelis were being obstinate, insisting that they were ready to negotiate over borders and that they would never consider returning to those that existed before 1967. The minute-taker’s addition of “subjects other than borders” seems to have been an attempt to credit Israel with a more productive negotiating position than it was staking out, and to credit Sisco with saying as much.

Discussion

The task of the minute-taker is to create an enduring record of ephemeral talk, usually on the basis of notes taken in real time, without the benefit of an audio recording. This is especially challenging when talk is animated and speaking turns are negotiated informally rather than imposed by a rigid question-and-answer structure (as in a courtroom) or allocated by a single authority (as in many college seminars). In such circumstances, even an experienced minute-taker needs to make choices about what to include and what to omit, particularly if they are not trained in shorthand or stenography, and even a specialist would be challenged to capture overlapping talk, side conversations, and fleeting disfluencies.

This article attempted to reconstruct some of the practices used by National Security Council principals and staff members to accomplish this, or at least to give the impression that it was so accomplished. To be sure, there is no doubt much that was idiosyncratic both about the minute-takers and the circumstances in which they operated. Yet those practices are arguably among those available to anyone so tasked, and thus a reflection of what is generic to the work of minute-taking, permitting for some generalizations.

One minute-taking practice is omission, or deletion—ignoring content because it does not seem sufficiently important or relevant; a minute-taker may also fail to hear some words, especially if he or she is busy writing notes on something said a moment earlier. Another practice is paraphrasing in such a way as to transform many spoken words into a small number of written ones. (Bundy and McCone also simply noted entire discussions on some topic, without elaborating.) A third practice is the use of shorthand, including both abbreviations and skeletal grammar, such as that used by Bromley Smith. Another thing minute-takers do is disambiguate, so as to produce a record intelligible to outsiders, including of talk that was originally muddled or intentionally oblique; this arguably goes beyond mere paraphrasing, and makes the minute-taker’s job harder rather than easier insofar as it requires interpretive work. Any of these practices may undermine the veridicality of the final minutes: important material may be omitted; paraphrases may be imprecise; grammatical shorthand may require the subsequent manufacture of the dropped words (e.g., modal verbs); and a minute-taker’s guess about what someone intended to say may be incorrect. Moreover, while particular alterations in meaning may lend themselves to innocuous explanation, when the final product portrays the group as, for instance, more unified, confident, and high-minded than it was, systematic image-crafting may be at work (as in Anteby and Molnár Reference Anteby and Molnár2012; Stark Reference Stark2012), something made possible by the shared understanding that minutes are an unavoidably incomplete representation of talk, as well as by the possibility of subsequent edits to that representation.

Forty years ago, Neisser (Reference Neisser1981) compared the Watergate testimony of Nixon’s former counsel, John Dean, about key White House meetings with transcripts of recordings secretly made by Nixon of said meetings, as a sort of natural experiment in conversational recall. Though Dean was, at the time, credited with having an excellent memory, this was more on the basis of his self-assurance than actual accuracy: Dean repeatedly misremembered the details of particular meetings, inventing some details, forgetting others, and mistaking when key remarks were made. Yet, Neisser credits Dean with correctly remembering the most important facts, that there was a cover-up and Nixon knew about it. As Edwards and Potter (Reference Edwards and Potter1992) point out, however, what counts as “most important” depends on one’s perspective, and we only judge Dean’s testimony favorably because of the very outcome it helped to shape: Nixon’s resignation. Similarly, we might be tempted to say that, for some purposes, the four minute-takers preserved the important bits of the meetings, but “importance” is a judgment rendered after the fact from a particular perspective.

The Senate Watergate Committee ultimately acquired the recordings and was able to judge the accuracy of Dean’s testimony for itself and reached about the same conclusion as Neisser. But in the Iran-Contra affair hearings, Congress had to rely on Oliver North’s testimony about conversations, as well as his contemporaneous notes, even though the latter may have been crafted with the expectation that they might later be scrutinized; in addition, North destroyed many records before they could fall into the hands of investigators (Lynch and Bogen Reference Lynch and Bogen1996), further shaping the documentary record for which he was subsequently held to account. Granted, the minutes examined here were not similarly featured in subsequent inquiries. Nevertheless, Iran-Contra is a reminder that records of talk can become consequential, and that when access to recordings is impossible, the practices that went into the creation (and preservation) of those records can acquire more than just academic interest.

Investigations aside, the foregoing is important to several areas of scholarly inquiry. First, it matters for organizational behavior, inasmuch as subordinates read minutes for clues about what their superiors want and what beliefs they are espousing. “When the individual decides upon a particular course of action, some of the premises upon which this decision is based may have been imposed upon him by the exercise of the organization’s authority over him” (Simon Reference Simon1976: 123), and minutes may provide valuable clues as to what those premises should be.

Second, the analysis sheds light on an important moment in the process of creating organizational records, something of interest to ethnomethodologists (Garfinkel Reference Garfinkel1967; Meehan Reference Meehan1986; Whittle and Wilson Reference Whittle and Wilson2015) as well as to scholars of organizational memory, inasmuch as written records are one repository for such memory (Anteby and Molnár Reference Anteby and Molnár2012; Lynch Reference Lynch2009).

Third, the results have unsettling implications for scholars who have no choice but to trust the accuracy of minutes (e.g., Anderson Reference Anderson1983; Bernstein Reference Bernstein1980). If all we had were the minutes, we would not know, for instance, of the repeated arguments made on October 25, 1962 in favor of intercepting the East German passenger ship, or of McNamara’s call for intercepting a ship carrying weapons for the evidence this would furnish. And we would be deprived of much evidence of who agreed with whom, for several reasons. One is that brief expressions of agreement were generally ignored. Another is that Nixon’s minute-taker sometimes consolidated congruent remarks into one turn attributed to a single individual. A third is that Bromley Smith sometimes interpreted attempts at formulating (restating) someone’s position as agreement with it.

Or consider my own research on the Cuban Missile Crisis (Gibson Reference Gibson2011). I show how, in the first five days of the crisis, the ExComm made the blockade option palatable by suppressing talk about the dangerous path it put the United States on, namely that it virtually guaranteed that a later airstrike, which the group thought highly likely, would be against operational missiles as the blockade would give Soviet technicians time to finish their work. However, Kennedy only recorded three meetings during this period: two on Tuesday, October 16, and one on Thursday, October 18. There is no recording for an evening meeting on the eighteenth or the crucial meeting on Saturday, October 20, when President Kennedy basically chose the blockade, because these meetings were held in the Executive Mansion, rather than the Cabinet Room, to escape notice by the press. Nor were more informal meetings of ExComm members, held while the president was traveling on the nineteenth, recorded. For the Saturday meeting, however, we have minutes (though we do not know who took them). These seem to support my story of the continued suppression of talk about the risk of later having to bomb operational missiles, a pattern that began on the eighteenth (and was captured on tape). However, the foregoing analysis should caution us about reaching any conclusions about what arguments were not presented. Thus, the most that can be said is that, so far as we know, the suppression that began earlier continued on the twentieth.

In conclusion, minutes provide scholars, like subordinates, traces of words uttered behind closed doors, but they often have the appearance of a verbatim report, and even when they do not, it is tempting to read them that way, lulling us (and perhaps organizational members) into erroneous conclusions about who said what, how they said it, and whom they were in agreement with. This study provides a rare glimpse into minutes’ production, made possible by the rare coincidence of tape recording and minute-taking by NSC principals and staff members who never anticipated this degree of scrutiny.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2022.4

Acknowledgements

For suggestions I am grateful to Benjamin DiCicco-Bloom, Anna Geltzer, John Martin, Paul McLean, Ann Mische, and Philip Zelikow; participants in Notre Dame’s Culture Workshop; an audience at Bentley University, particularly Anne Rawls, Angela Garcia, and Jason Turowetz; and two anonymous reviewers.