Introduction

In-work conditionality (IWC) was introduced in 2012 by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government (2010-2015) as part of Universal Credit (UC), a major welfare reform merging six in- and out-of-work means-tested benefits (Millar and Bennett, Reference Millar and Bennett2017). The introduction of IWC means, for the first time, working recipients of means-tested benefits must engage with employment services and take steps to increase their earnings, such as applying for additional or alternative jobs, towards the aim of reducing their reliance on means-tested benefits (Economic Affairs Committee, HL, 2020: 64). Failure to comply with these requirements could result in a reduction or suspension of benefit payments, known as sanctions (DWP, 2020b). The introduction of IWC therefore marks a shift in policy concerning the labour market integration of low-income working households from a ‘carrot’ approach consisting of financial incentives to the use of ‘sticks’ in the form of mandatory requirements bolstered by punitive mechanisms (Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014: 31).

The legitimacy of the shift has been questioned yet underexamined in academic research. In particular, there are competing arguments about the extent to which, and reasons why, political actors and citizen-voters might support or oppose IWC (Abbas and Jones, Reference Abbas and Jones2018). For example, the high levels of public support for reforms by previous governments intensifying punitive work-related activation, especially in unemployment benefits, indicates there could be appetite for extending this approach to other groups of benefit recipients (Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby, Park, Curtice, Thomson, Bromley and Phillips2004; Sage, Reference Sage2012; Fossati, Reference Fossati2018; Sage, Reference Sage2019). However, public perceptions of the relative deservingness of working households could drive opposition to IWC, especially if IWC is seen to put unwarranted demands and constraints on a group already contributing to society through paid work (van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2006; Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014: 31). Indeed, the Conservative government’s ambiguous communication of IWC so far, including framing it as part of its broader ‘in-work progression’ policy (DWP, 2019a; SSAC, 2017), suggests support for IWC among prospective voters and/or within the party is limited.

This article therefore takes a first step towards examining the politics of IWC, focusing on the relationship between the policy preferences of citizen-voters and political parties’ policy-seeking and vote-seeking behaviours in post-industrial societies (Pierson, Reference Pierson1994; Beramendi et al., Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015). Specifically, we analyse the levels and determinants of public support for IWC using data collected in August 2017 through an online survey with a sample of 1,111 adults in the UK. We also examine the positions, rationales, and strategies of political parties and their representatives towards IWC using parliamentary and manifesto data. Our findings indicate that, overall, IWC is a partisan policy with voters split along traditional economic cleavages. Yet, exceptions, such as the divide between Conservative parents and those without children, may have ramifications for parties’ strategies in supporting or opposing the reform.

The article first outlines the relevant policy background. The next section presents the theoretical framework, followed by a section on the data and methods. The empirical analysis of parliamentary debates, party manifestos and public attitudes follows. The final section discusses what the analysis adds to our understanding the politics of IWC, as well as its limitations and avenues for future research.

Policy background

IWC is a form of ‘conduct conditionality’ whereby entitlement to social benefits is dependent upon recipients’ fulfilment of behavioural requirements (Clasen and Clegg, Reference Clasen, Clegg, Clasen and Siegel2007: 172). Although conduct conditionality has become increasingly common across advanced welfare states following the activation turn of the 1990s, it is central to the UK’s ‘work-first’ activation model, in which unemployed individuals’ entitlement to social security is conditional on requirements to search for, apply for, and accept jobs, with relatively harsh penalties, known as sanctions, for non-compliance (Lindsay, Reference Lindsay, Serrano Pascual and Magnusson2007; Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014; Langenbucher, Reference Langenbucher2015; Immervoll and Knotz, Reference Immervoll and Knotz2018). In contrast, up until the introduction of IWC within Universal Credit in 2012, low-income families combining cash benefits with paid work were not subject to conduct conditionality, with policies for these groups designed to incentivise rather than enforce certain behaviours (Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014: 31).

Until recently, means-tested benefits for households categorised as inwork and those categorised as unemployed have followed distinctive reform paths (Clegg, Reference Clegg2015). The Conservative government’s Jobseekers Act of 1995 is considered a ‘watershed moment’ as it ‘intensified’ the monitoring of unemployment benefit recipients’ job search behaviour in light of concerns about welfare expenditure and claimants’ attitudes (Watts et al., Reference Watts, Fitzpatrick, Bramley and Watkins2014: 3). However, this approach was not applied to in-work benefits. Similarly, from 1997, New Labour sought to ‘take tough measures’ by intensifying conduct conditionality, including for disabled people and lone parents, while expanding support for working households to ‘extend opportunities’, promote social inclusion through work and reduce child poverty (Blair, Reference Blair1996; Walker and Wiseman, Reference Walker and Wiseman2003; Patrick, Reference Patrick2012; Fletcher, Reference Fletcher2014).

This separation has become less clear-cut. The Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government, elected in 2010, increased sanctions attached to out-of-work benefits to their highest levels, justified on the grounds that out-of-work claimants are workshy, lazy and scrounging from the state, and also retrenched in-work benefits (Patrick, Reference Patrick2012; Dwyer, Reference Dwyer, Horsfall and Hudson2017; Fletcher and Wright, Reference Fletcher and Wright2018: 329; Watts and Fitzpatrick, Reference Watts and Fitzpatrick2018: 9). The introduction of Universal Credit in 2012, which merges in- and out-of-work benefits and extends conduct conditionality to working households, blurs the distinction between these groups (Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014: 31). Later Conservative governments also weakened conduct conditionality from previous record high levels, with the maximum sanctioning period reduced from three years to six months (DWP 2019b; Sage, Reference Sage2019), suggesting a softening of punitive mechanisms for out-of-work households.

More specifically, IWC means that some working recipients of UC with earnings below a defined threshold could be required to take steps to increase their earnings. The earnings threshold is approximately thirty-five hours per week at the level of the statutory minimum wage, or lower for claimants with limited work capacity (e.g. because of disabilities or caring responsibilities) (Economic Affairs Committee, 2020: 64–66). The requirements, which are mandated in a contract (the ‘Claimant Commitment’) drawn up with employment services, are not clearly defined by the government, but could include asking a current employer for a pay rise or more hours of work, applying for alternative jobs with better pay or hours, and/or applying for additional jobs (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Berry, Rouse and Whittle2019: 4; DWP, 2020a).

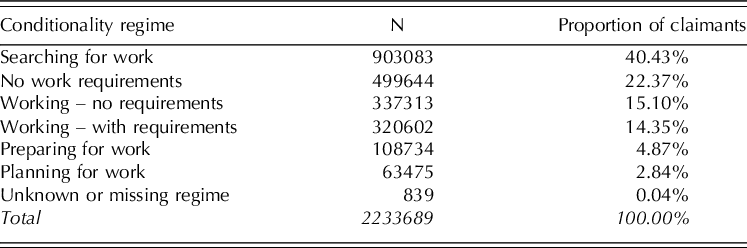

Early analysis argued that the sanctions bolstering IWC would be tough (Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014: 30–31). However, according to the Department for Work and Pensions’ statistics (2020b), UC claimants categorised as ‘Working – with requirements’ were required to undertake work-related requirements with a conditionality regime that is ‘less frequent and lighter’ than for unemployed claimants and those with very low earnings (DWP, 2020b). From January 2019 – 2020, just under a sixth of all UC claimants were registered under the IWC regime (Table 1). This shows that UC still partly distinguishes recipients’ conditionality regime on the basis of work-status, even if the extension of conduct conditionality to working households nevertheless marks a significant shift (Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014: 31).

Table 1 Universal Credit conditionality regimes

Notes: Authors’ calculations. Average claimants in each group based on monthly figures for Jan 2019 - Jan 2020. Source: DWP, ‘Number of people on Universal Credit by conditionality regime’. Accessed at: https://stat-xplore.dwp.gov.uk/.

The ambiguity surrounding IWC is partly because employment service staff members are afforded some discretion in setting requirements and applying penalties (DWP, 2020a). These details were also not confirmed in the original legislation and the government tested different applications of IWC after it became law, finding limited evidence that more intensive requirements lead to a minor increase in earnings (DWP, 2018; 2019a). This apparent caution in the application and communication of IWC indicates the government may not be convinced of the effectiveness of the policy – indeed, there is a limited evidence base for IWC – and/or it may be aware of legitimacy issues among its prospective voters. The next section therefore sets out our framework for analysing the relationship between citizen-voter attitudes towards IWC, and political parties’ vote-seeking and policy-seeking behaviour (Beramendi et al., Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015).

The politics of punitive (in-work) conditionality

Our framework focuses on the relationship between citizen-voter attitudes and political parties’ vote-seeking and policy-seeking behaviour, and integrates insights from traditional and new perspectives on the politics of social policy (Bonoli and Natali, Reference Bonoli, Natali, Bonoli and Natali2012; Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Picot and Geering2013; Beramendi et al., Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015). Traditional perspectives map the preferences of voters and political parties on a single left-right dimension and assume alignment between parties and their voters on the basis of industrial social class (Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Picot and Geering2013: 221). This perspective would suggest that left parties oppose IWC, as IWC restricts entitlement to benefits that their working-class voters are more likely to receive. Similarly, right-wing parties would support IWC because reducing entitlements to welfare appeals to voters further along the income distribution who may stand to gain from lower social expenditure and taxation. Indeed, both those that identify as left wing and those on a low income or unemployed are more likely to oppose conduct conditionality applied to unemployment benefits (Larsen, Reference Larsen2008; Achterberg et al., Reference Achterberg, van der Veen and Raven2014; Fossati, Reference Fossati2018)

However, several interrelated factors require us to go beyond the traditional view. First, IWC relates to areas of contestation that transcend or nuance conflict relating to more or less tax and expenditure. For example, the government frames IWC in UC as support for low-income working households to progress in the labour market (Millar and Bennett, Reference Millar and Bennett2017: 177). This goal conceivably aligns with a social investment agenda to foster inclusion of groups at risk in post-industrial societies and therefore could appeal to parties and/or voters, including those on the left, supportive of these ideals (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2012: 114–115, 119). However, IWC within UC defines ‘progression’ in the labour market primarily with reference to earnings, which likely limits the scope of employment support provided to claimants (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Berry, Rouse and Whittle2019: 15). IWC may therefore be viewed as aligning with work-first ideals that emphasise supply-side barriers to progression (Häusermann, Reference Häusermann2012: 119).

Relatedly, IWC could also relate to preferences for punitive welfare, i.e. the use of penalties to punish undesirable behaviour. Studies suggest there are distinct preferences for punitive policies that do not necessarily map on to economic interests (Achterberg et al., Reference Achterberg, van der Veen and Raven2014: 217). Political parties and voters may be supportive of IWC if they believe working households in receipt of benefits should be penalised when their behaviour is socially undesirable e.g. when they are not working as hard as they can be and are claiming benefits to make up for their lack of earnings (Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014: 31). This could also work in reverse – e.g. opponents may reject IWC on the basis that it is unnecessarily punitive.

However, the dimensions of conflict among parties and voters that are likely to be emphasised in the debate on IWC should also be considered in light of a changing context of welfare state politics. In post-industrial societies, socio-economic transformations have shifted the composition of the electorate, including in the declining proportion of industrial working-class voters, driving partisan dealignment and prompting efforts from political parties to reconcile multi-dimensional policy preferences of new coalitions of voters (Bonoli and Natali, Reference Bonoli, Natali, Bonoli and Natali2012; Beramendi et al., Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015). Importantly, the decline in the size of the industrial working class has prompted many left-wing parties to appeal to middle-income voters by expanding social investment and activation, such as in-work benefits, and fiscal constraint in other areas (Gingrich and Häusermann, Reference Gingrich and Häusermann2015). Thus, the precise framing and application of IWC in ways that are conducive to activation are likely to influence its support among middle-income voters.

Moreover, growing inequalities based on education are argued to have driven the emphasis on the ‘cultural’ dimension of welfare politics by political parties aiming to appeal across groups with possibly divergent economic interests (Bovens and Wille, Reference Bovens and Wille2017; Iversen and Soskice, Reference Iversen and Soskice2019). Studies show that lower levels of education are associated with greater support for sanctions in unemployment benefits (Achterberg et al., Reference Achterberg, van der Veen and Raven2014). As individuals with lower education are more likely to receive these benefits, some attribute these attitudes to the relationship between education and authoritarian values (Knotz, Reference Knotz2016) or notions of deservingness (Van Oorschot, Reference van Oorschot2000). Indeed, Labour and Conservative governments have utilised authoritarian frames, such as being ‘tough on welfare’, to justify conduct conditionality, while political parties trying to appeal to university graduates have critiqued punitive welfare in later years (Sage, Reference Sage2019). The conflict surrounding IWC could therefore lie on the cultural axis with patterns of public support mirroring educational divisions, depending on the emphasis on and application of its punitive elements.

However, cutting across the previous points is the argument that political parties’ and voters’ preferences are not formed in a vacuum (Bonoli and Natali, Reference Bonoli, Natali, Bonoli and Natali2012). IWC could find support if it is perceived to be the best option to address new challenges in a constrained policy context. In the UK, there are concerns that UC could disincentivise work because, as a merged in- and out-of-work benefit, it does not have a minimum working hours threshold for eligibility. In contrast, the outgoing Working Tax Credits are conditional on employment of at least sixteen hours a week (for those aged twenty-five to fifty-nine without children the minimum number of hours is thirty) (Finch, Reference Finch2016: 31). The rate at which UC is withdrawn is also expected to reduce work incentives for some households (Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014: 30). IWC may be considered a necessary fix to issues of work incentives under UC, where alternatives, such as abolishing UC and returning to a previous system of in- and out-of-work benefits, are not considered feasible (e.g. because of sunk costs).

Finally, political parties’ understanding of the (dis)alignment between their policy-seeking and vote-seeking preferences are also likely to drive their position on, and framing of, IWC (Pierson, Reference Pierson1994; Bonoli, Reference Bonoli, Bonoli and Natali2012: 100). If parties expect their prospective voters to support IWC, they are likely to ‘claim credit’ for the reform by, for example, publicly expressing support and/or claiming ownership of the reform, its implementation and/or its ideas (in the case of parties that did not implement the reform), as was broadly the case for conduct conditionality in out-of-work benefits (Sage, Reference Sage2019: 100). Yet, if parties support or preside over IWC, and yet suspect their prospective voters could oppose the reform, they may adopt so-called ‘blame avoidance’ strategies, designed to minimise potential electoral harm of unpopular reforms (Pierson, Reference Pierson1994).

On the latter, if the government responsible for IWC implements a blame avoidance strategy, we might expect this to take one of three main forms (Vis, Reference Vis2016: 128-131, 137). The first is the manipulation of procedures by, for example, ‘agenda limitation’ (i.e. preventing decisions from being taken openly). The second is the manipulation of perceptions by, for example, ‘redefining the issue’ (i.e. mobilising new groups that may perceive the reform as in their interest) or ‘strategic re-framing/communication’ (e.g. downplaying less popular aspects of the reform in its communication). Finally, parties can manipulate payoffs through ‘exemption’ (i.e. exempting specific categories of opponents), ‘concentration’ (i.e. imposing losses on groups that are politically weakest) or ‘creative accounting and lies’ (i.e. redefining terms or measures).

Given the range of factors possibly influencing preferences for and positions on IWC, we do not set out precise expectations on the key question of whether politics parties and their voters are aligned on IWC and how or why. Instead, we examine the arguments parties use in support of or against IWC to gauge the coalitions of voters that parties are trying to mobilise and assess the kinds of blame avoidance or credit claiming strategies pursued. Individual-level factors associated with IWC preferences are also likely to indicate the dividing lines of the politics of IWC, and we examine if this resembles the income and educational divide found for other forms of welfare.

Data, variables and analysis

We examine the preferences of voters and the preferences, rationales and strategies of political parties and their elected representatives in Parliament and Government concerning IWC. The study period, 2011 to 2020, is informed by the introduction of IWC in the Welfare Reform Bill, first presented to the House of Commons in early 2011. During this time, the UK voted to leave the European Union, there were three general elections (2015, 2017 and 2019) and high profile changes in the leadership of the main political parties. Yet welfare reform debates remained salient because of the introduction and implementation of UC. Changes in party leadership, especially the election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party, and the associated rise of the left wing of the party (Sage, Reference Sage2019), are nevertheless significant for our analysis because they coincided with a shift of position on welfare issues that subsume IWC, including punitive welfare and the question of whether to keep or abolish UC. Party positions on IWC were gauged primarily through analysis of MPs’ contributions in Parliament and secondarily through party manifestos for the 2015, 2017 and 2019 general elections (UC was not announced prior to the general election in 2010). Relevant contributions were identified through searches of Parliamentary records online, the records of the Public Bill Committee (PBC) of the Welfare Reform Bill, and in manifestos, using the keywords ‘in-work conditionality’ and ‘in-work progression’. The searches and sources included in the analysis are summarised in the Supplementary Material (Tables A-C). MPs’ contributions were coded systematically using NVivo 12 Software (NVivo, 2020), starting with broad preferences (e.g. support) and characteristic nodes (e.g. political party), followed by thematic coding of the associated arguments (e.g. reduce welfare expenditure). The manifestos searches yielded no relevant references (Conservative Party, 2015; 2017; 2019; Green Party of England and Wales, 2015; 2017; 2019; Labour Party, 2015; 2017; 2019; Liberal Democrats, 2015; 2017; 2019; Scottish National Party, 2015; 2017; 2019). Yet the manifestos form part of the analysis as they show parties’ positioning and strategic communication to voters on the overarching topic of conduct conditionality and welfare reform (Budge et al., 2001). Moreover, the only time IWC was debated before becoming law was in the Public Bill Committee (PBC). The policy debates in PBCs differ from those in the main chamber of the House of Commons because their purpose is to scrutinise the proposed legislation line by line in ‘an arena in which MPs are not vying for press coverage of their comments’ (Thompson, Reference Thompson2016: 44). PBC members are selected primarily by their party’s leadership (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Morris and Larkin2013: 11) and are proportional to party representation in Parliament. The success rate of non-government amendments to legislation is therefore very low (Thompson, Reference Thompson2016: 42). We therefore focus on what MPs say during PBCs, rather than what they do (e.g. table amendments), to gauge parties’ policy-seeking intentions on IWC.

We also analyse voter preferences using data from an online, cross-sectional survey data conducted by a professional polling company, IPSOS-Mori, in August 2017, on behalf of researchers from the Institute for Policy Research at the University of Bath. A representative sample of 1,111 adults aged eighteen to seventy-five in the UK was drawn from IPSOS-Mori’s (non-representative) omnibus panel and post-stratification weights constructed based on population statistics sourced from Eurostat. The use of an online survey raises concerns about the sampling procedure, e.g. the under-representation of certain groups, especially the digitally excluded, and data quality, e.g. respondents providing satisficing answers (Frippiat et al., Reference Frippiat, Marquis and Wiles-Portier2010). There is an over-representation of Labour voters in the sample relative to their 2017 election performance, even after weighting. Nevertheless, we found highly comparable results in a near identical question on unemployment benefit conditionality in the European Values Study conducted in the UK less than a year later between February and July 2018 (see Table E in the Appendix).

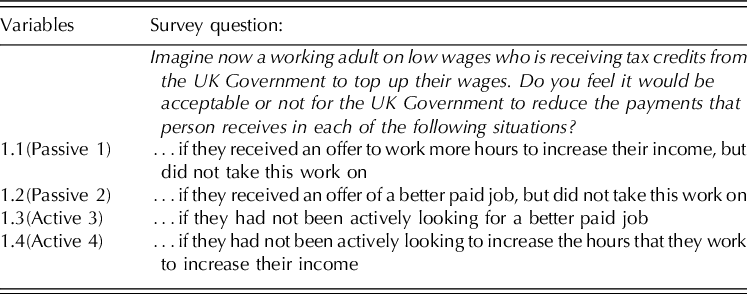

Attitudes to IWC were analysed using dependent variables comprising four survey items.

IWC was described in the survey with reference to tax credits for households undertaking paid work. Yet the description of IWC closely resembles that which it is suggested is in place in UC. UC was not explicitly referenced in the question because it is high profile and politicised as a flagship government policy (Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014; Millar and Bennett, Reference Millar and Bennett2017). Tax credits for working households are less politically aligned (Clegg, Reference Clegg2015). Our aim was to isolate (to some degree) attitudes to IWC, rather than measure attitudes to UC as a whole.

The survey items differentiated between four types of in-work conditionality: two ‘passive’ and two ‘active’ (see items 1.1 to 1.4 in Table 2). Passive in-work conditionality reduces benefits if recipients turn down an offer of more hours of work or an offer of a better-paid job. The active forms of in-work conditionality reduce benefits if recipients did not actively look for a better-paid job, or opportunities to increase their hours of work. Respondents were asked whether each was ‘Acceptable’ or ‘Not acceptable’. A third ‘Don’t know’ response was included.

Table 2 Overview of in-work conditionality dependent variables

We converted the four IWC survey items into a binary variable to carry out logistic regression analysis. This involved four coding stages: (1) Each item was coded as 1 for pro-IWC responses (‘Acceptable’), -1 for anti-IWC responses (‘Unacceptable’) and 0 for ‘Don’t know’; (2) The items were summed giving a range of -4 to 4; (3) Values -4 to 0 were recoded as 0, while values 1-4 were recoded as 1; (4) Respondents who answered ‘Don’t know’ to all four items were coded as missing (N= 90, 8.1 per cent). Thus, the binary variable identifies those that were more supportive of IWC across the four items than they were opposed, while excluding those with no opinion at all.

Independent variables were included to explore both socioeconomic characteristics and political partisanship as determinants of attitudes to IWC. These included age (continuous), highest level of education (GCSE level, A level or Degree and above), gender, whether respondents had children in their home (dummy), household income (<£20k a year, £20k-£35k a year, £35k a year+ and Prefer not to say) and employment status (full-time, part-time, self-employed, unemployed, retired and not employed). Political party choice at the last general election (2017) was used to test for the relevance of political partisanship. The sample was too small for individual analysis of the parties other than Conservatives and Labour in the regressions, but these are included (as ‘other’ parties). Attitudes to conduct conditionality within unemployment benefit (see Table E in Appendix) were also included in a final model to test whether opposition to conditionality in general may explain the relationship between variables: ‘Don’t know’ responses (2.89 per cent) were coded as missing. Responses 1-5 were coded as support for conduct conditionality (1) and 6-10 were coded as opposition.

Findings

In-work conditionality in the Parliamentary arena

During the Welfare Reform Bill PBC in 2011, Labour MPs raised questions about the lack of detail of IWC in legislation, and proposed limiting its application, rather than outright opposition. They pressed for details on the earnings and work hours thresholds for applying IWC (e.g. Timms, PBC, 2011: c465), legitimate exemptions from IWC (e.g. Green, PBC, 2011: c464), the nature of behavioural requirements, the technological feasibility of monitoring earnings, and the level discretion afforded to employment advisers (Timms, PBC, 2011: c466-67). Opposition to punitive mechanisms concerned the use of a flat-rate financial penalty for non-compliance, which Labour MPs argued would disproportionately affect working households, whose benefit income is made up mainly of support for childcare and housing costs (e.g. Greenwood, PBC, 2011: c462).

During the PBC, the Minister of State (DWP), Chris Grayling MP, partly answered Labour’s demands for details, and circumvented others (PBC, 2011: c465). Preventing scrutiny of parts of IWC at this phase in the legislative process appears reminiscent of agenda limitation. Further, Grayling (ibid.: c466) suggested IWC would be applied reasonably as had been done by ‘governments of both persuasions over many years’ and that it will ‘operate in a similar way to out-of-work conditionality’. Emphasizing the status quo is suggestive of strategic (re)framing of IWC, which represents a shift in logic concerning conditionality. The argument that some groups are not expected to work-full time (e.g. lone parents with children in primary school) could represent concern about the (un)popularity of the reform among specific groups of voters (ibid.: c464).

The government rationalised the use of punitive mechanisms within IWC by emphasising undesirable behaviours: ‘We are saying to those who have said, ‘I will take a part-time job, then get a full-time job if I can’, only to turn round and say that they are not in fact willing to look for a full-time job, that they will face a sanction’ (ibid.: c464). Moreover, the Conservative MP, Charlie Elphicke, argued that IWC served to ‘roll back the benefits culture that has grown to excessive amounts over the past ten years’ (ibid.: c464), which could be interpreted as both vote- and policy-seeking behaviour, given the centrality of the notion of ‘welfare dependence’ to the Conservative welfare reforms in the past.

IWC also featured in debates in the House of Commons Chamber after the Welfare Reform Act became law (see Supplementary Material, Table A). The contributions suggest further strategic (re)framing by the government as Conservative MPs did not explicitly speak of applying sanctions to working claimants. For example, in response to a question on sanctions under IWC, the Minister for Employment, Priti Patel MP (HC Deb, 2016b) said:

Conditionality is a key part of the approach that has helped to deliver record-breaking levels of employment, labour market improvements and the lowest claimant count since 1975…sanctions have been part of the welfare system for a considerable number of decades.

In the main, Conservative MPs’ justifications for IWC emphasised the aim to improve financial incentives for working households to increase their work effort. Additionally, the skills and attitudes of working recipients were also emphasised, which could be viewed with a social investment lens. For example, the Minister of State (DWP), Mark Doban, stated:

…we are aiming above all to achieve a fundamental change in attitudes to work… to help people move up the income scale and ways to increase their earnings by getting new skills, getting promotions and increasing their hours. (HC Deb, 2013)

The focus on attitudes and progression were echoed by DWP Minister, Justin Tomlinson’s (HC Deb, 2017a) example of a hypothetical working recipient of UC:

…I have been out of work for a long period, and…work in a supermarket… I turn up every day, work my hours diligently … The named work coach might say, “Have you thought about asking to become the supervisor?” The reply would be, “I’m too shy to do that.” The named coach would say, “No problem,” and then ask the supervisors and managers in the store, “Is he ready to take that step up?” Therefore, the coaches help people to progress in the workplace.

This example modifies justifications for out-of-work conditionality that emphasise the attitudes of ‘work-shy’ unemployment benefit recipients, suggesting instead some working recipients of income support lack the interpersonal skills or confidence to ask their employers about promotion. They are indicative of a ‘strategic reframing’ as IWC is defined as a continuation of the status quo with regards to sanctions, but also justified with regards to its potential to change attitudes and promote employment progression.

Somewhat differently, David Gauke (HC Deb, 2017d), the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions (2017–2018), goes furthest in painting a picture of working households as dependent on ‘substantial support from the taxpayer’ and ‘the state’. Here, working recipients of income support are framed as distinctive from other working households (‘the taxpayer’).

Opposition to IWC came from Labour and SNP MPs only. Like in the PBC, they criticised the lack of detail provided by the government on IWC in UC, and the limited evidence base for the reform. Moreover, Labour and SNP MPs argued that IWC would be stifled by cuts to employment services (HC Deb, 2017b) and benefits for working households (e.g. HC Deb, 2017c), suggestive of efforts to expose IWC as part of a retrenchment agenda.

SNP and Labour MPs argued that IWC was unreasonable and harmful for certain claimants – namely, lone mothers and those on non-standard employment contracts. For example, Labour MP Jessica Morden (HC Deb, 2018) spoke of a single mother in her constituency ‘who loves her permanent, part-time job in a school… with the potential shortly to go full-time’ and who, while receiving UC, was being asked to move into temporary work in the retail sector over the Christmas period ‘with no guarantee of work afterwards’, asking: ‘Why is this in anyone’s interest? Making someone in work worse off is not work progression.’ Similarly, Dr Whiteford, the SNP Shadow Spokesperson for Work and Pensions (2010 -2015) stated that ‘extremely’ hard-working people ‘in low-paid, tiring and not exactly pleasant jobs’ are often ‘juggling family responsibilities, looking after children or, increasingly, elderly and infirm relatives’ (HC Deb, 2016a).

These arguments highlight individual challenges faced by recipients and their deserving attitudes as reasons against applying IWC to certain groups. While emphasising the social and economic impact of the reform on select groups, it also echoes divisive justifications for conduct conditionality for out-of-work claimants which contrast those ‘doing the right thing’ (i.e. working hard) with other recipients (e.g. those not working hard), employed by previous Labour and Conservative governments.

MPs considered to be more towards the left of the Labour Party, typically those holding senior positions under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, combined arguments about the problem of IWC for certain recipients with a broader critique of punitive welfare and austerity, aligning with the position in the Labour Party’s 2017 and 2019 manifestos to abolish sanctions (e.g. Thornberry, HC Deb, 2015). Similarly, Laura Pidcock (HC Deb, 2017c), then shadow Employment Minister, argued that her constituents should not be fearful of the DWP, but that it should instead offer ‘hope, security and guidance’.

IWC and electioneering

Neither IWC nor in-work progression feature in the party manifestos for the 2015, 2017 and 2019 general elections. One possible explanation is the technical nature of the reform. However, the parliamentary contributions above suggest IWC can be communicated in non-technical terms to voters, should parties want to support or oppose it. The Conservative Party’s manifestos do not mention IWC specifically, but pledge to reform their flagship policy, UC, so that it ‘pays to work more hours’ (e.g. Conservative Party, 2019: 17).

The absence of IWC in opposition manifestos could indicate that parties perceive it to be a low salience issue or narrow issue, and/or that parties’ policy-seeking intentions regarding IWC are not clear. The manifestos suggest support for the former explanation: the Liberal Democrats, SNP, Labour and the Greens 2015, 2017 and 2019 manifestos pledge to reform and/or completely abolish UC, which would therefore also likely lead to the abolition of IWC. Moreover, from 2017 onwards, all opposition parties adopt a stronger critique of sanctions pledging to remove them from the social security system altogether. For example, the Labour Party (2019: 73) pledged to ‘…immediately suspend the Tories’ vicious sanction regime,’ disassociating itself from the use of punitive mechanisms by previous Labour governments. In contrast, the Liberal Democrats (2019: 65) proposed to replace punitive welfare with a system of financial incentives. However, critiques of sanctions refer mainly to unemployed recipients.

Voter preferences and in-work conditionality

Table 3 summarises the weighted responses for the four survey questions on in-work conditionality. The results indicate that the majority of voters support the principle of a passive form of IWC that would see benefits reduced for recipients turning down an offer of better-paid work (54 per cent support, 29 per cent oppose) or more hours of work (50 per cent support, 33 per cent oppose). However, active forms of IWC revealed a plurality of respondents opposed sanctions for not searching for better-paid work (36 per cent support, 45 per cent oppose) or not searching for more hours of work (36 per cent support, 42 per cent oppose).

Table 3 Voter preferences for four in-work conditionality types

While a high proportion of ‘Don’t know’ responses for all four IWC questions could suggest indifference or lack of understanding from nearly 20 per cent of respondents, only eight per cent of respondents answered ‘Don’t know’ to all four questions, suggesting that most had a formulated opinion on at least one of the requirements (see Table D in the Supplementary Material for the breakdown of ‘Don’t know’ responses by party).

Overall levels of support and opposition are helpful for gauging the social legitimacy of IWC, but parties are also concerned with the views of specific groups that they identify as potential voters. Figure 1 summarises the responses according to party preference for the 2017 general election. The findings indicate there is a stark partisan divide between voters of the two main parties in preferences for IWC. Support for IWC was much higher among Conservative voters than among Labour voters and voters of other parties. The pattern of higher support for passive IWC than for active IWC is consistent across all voters, despite different levels of support among each party.

Figure 1. Support for in-work conditionality by party support. The Y-axis shows the proportion of respondents agreeing it is ‘Acceptable to reduce payments’ when a recipient of in-work benefits (a) turned down an offer of more hours, (b) turned down an offer of a better paid job, (c) did not actively search for more hours, (d) did not actively search for a better paid job. The denominator includes ‘Don’t Know’ responses. The X-axis shows a respondent’s recalled vote in the 2017 general election. DNV = did not vote, N/A = respondent did not provide an answer or did not know.

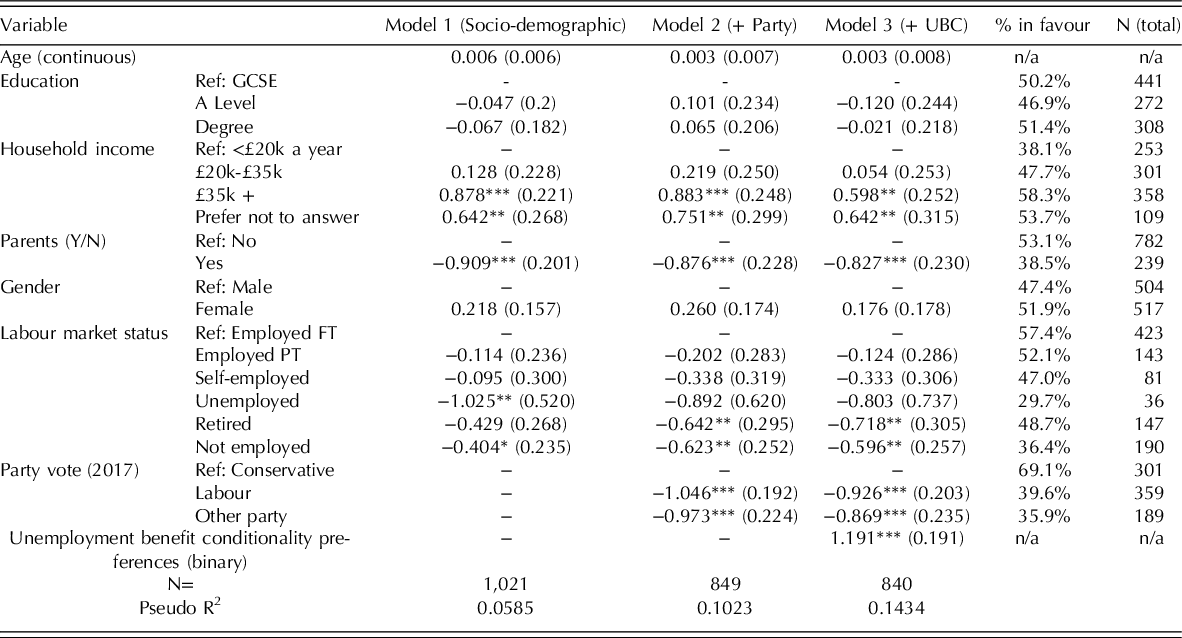

Preferences for IWC were analysed using a binary variable distinguishing between those more in favour of IWC across the four survey items versus those that are not. Logistic regression models predicting attitudes to IWC are shown in Table 4. Three models were constructed to regress support (in favour of) for in-work conditionality. Model 1 includes education, income categories, a dependent children dummy (‘parents’), gender, and labour market status. Model 2 adds political party preferences and Model 3 adds attitudes to unemployment benefit conditionality. The last two columns in Table 4 show the proportion of respondents within that category in favour of IWC and the total number of respondents in the sample to aid the interpretation of the regression results.

Table 4 Multivariate logistic regression models predicting support for in-work conditionality

The results of the regression analyses further highlight the significance of the relationship between political partisanship and attitudes to IWC. Compared to the reference group (Conservative voters), voting for Labour and ‘other’ parties have a significant negative effect on support for IWC even with the inclusion of sociodemographic covariates. The effect size was reduced partly when controlling for unemployment benefit conditionality preferences, but nevertheless remains highly significant.

The results also indicate that economic interests are likely to be an important driver of attitudes to IWC. Belonging to the highest income group is associated with significantly higher support for IWC (compared to the low-income reference group) across all three models. Considering the multivariate nature of the model, the increase in the coefficients for income between Model 1 and Model 2 indicates that, even when controlling for political party preferences, there is a significant effect of income on support for IWC. This means, for example, that even among Labour voters, who are significantly more likely to oppose IWC compared to Conservative voters, there is an independent, positive effect of income on their support for IWC. The negative and significant effect of unemployment in Model 1 is also in line with the argument that economic interests would lead to opposition to IWC. The effect becomes insignificant with the inclusion of party preferences in Model 2, indicating unemployment and party preference are correlated, although it is also primarily due to the small sample of unemployed respondents. On the other hand, part-time employment and self-employment are not significantly related to attitudes to in-work conditionality, compared with full-time employment, in any model. The former is particularly surprising given part-time workers are more likely to be subject to in-work conditionality than full-time workers.

The consistently significant negative effect of having dependent children on support for in-work conditionality is also a striking finding. One explanation could be that individuals with additional caring responsibilities view IWC as at odds with their caring responsibilities, which aligns with the challenges to IWC made by some Labour and SNP MPs in Parliament.

Employment statuses furthest removed from the labour market – retired and not employed – have a significant negative effect on support for IWC, compared to full-time employment. The result only becomes significant for retired individuals in Models 2 and Models 3, indicating that this only holds when controlling for their greater propensity to vote Conservative and support unemployment benefit conditionality. The effect and significance of those not employed also increases in Model 2. Similar to the negative effect of parenthood, this may be because these groups value and/or rely on the unpaid work of those potentially affected by IWC, such as care work. Contrary to this assumption, gender is insignificant, with women, if anything, slightly more likely to be in favour of IWC.

Education, typically a strong predictor of authoritarian values, is also not significant in any of our models. This casts doubt on the idea that IWC is likely to cut across the economic left-right dimension of politics and tap into the educational cleavage across advanced democracies. Table F shows that higher levels of education are a significant predictor of opposition to unemployment benefit conditionality, as found in other studies, suggesting it is not simply the sample or the contemporary UK context behind the null result. While support for unemployment benefit conditionality (binary) was strongly and significantly related to support for IWC, even when controlling for party preference and the other socio-demographic factors, there are important distinctions between the types of voters split on these issues.

The importance of voter mobility in the theoretical framework, and the findings thus far, warrant further probing of variation of preferences among those who voted for the two main parties in 2017. Figure 2 further illuminates the limited differences between voters’ attitudes to IWC across levels of education, age and gender, as found in the regression analysis. The graphs indicate there is more division among Conservative voters than Labour voters. The most striking within-party conflict is among Conservative voters with and without dependent children, with over 20 per cent difference in the levels of support. There is also a larger divide between the oldest age bracket (55-75) and the middle-aged bracket (35-54) as well as those with A level and Degree qualifications among Conservative party voters compared to Labour voters. This points to potential problems for the Conservatives with certain groups of voters, despite a majority of their supporters broadly in favour of the policy.

Figure 2. Support for in-work conditionality by party vote and education/gender/age/parental status. The Y-axis shows the proportion of respondents that agreed it was ‘Acceptable to reduce payments’ more often than they agreed it was ‘Unacceptable to reduce payments’ across the four survey items that asked about a recipient of in-work benefits that (a) turned down an offer of more hours, (b) turned down an offer of a better paid job, (c) did not actively search for more hours, (d) did not actively search for a better paid job. The denominator excludes respondents that stated ‘Don’t know’ to all four items. The X-axis in the top-left quadrant shows a respondent’s recalled vote in the 2017 general election and their highest level of education (GCSE-level or lower, A-level or similar and undergraduate degree or higher). X-axis in the top-right quadrant shows a respondent’s recalled vote and their self-identified gender. The X-axis in the bottom-left quadrant shows a respondent’s recalled vote and their age group (18-34, 35-54, 55-75). The X-axis in the bottom-right quadrant shows a respondent’s recalled vote and whether they had children under the age of 18 living in their household. DNV = did not vote, N/A = respondent did not provide an answer or did not know.

Discussion

The literature on the ‘new’ politics of social policy suggests that conflicting interests and ideals concerning who should get what, and the conditions of these entitlements, are often held across groups of voters that political parties must mobilise in order to win elections (Häusermann et al., Reference Häusermann, Kurer and Traber2019), prompting parties to employ strategies to limit the electoral harm of unpopular reforms and, to a lesser extent, to capitalise on (aspects of) policies they expect to be popular among target voters (Bonoli, Reference Bonoli, Bonoli and Natali2012; Vis, Reference Vis2016).

To some extent, our analysis suggests the politics of IWC are not so complex, with mainstream political parties and their voters in recent elections, differentiated predominantly by income group, broadly aligned. A Conservative government introduced IWC as part of its flagship reform, Universal Credit, and Conservative voters were more likely to support IWC. Similarly, the Labour Party shifted from a critical yet accepting position on IWC and UC to a much stronger oppositional stance on punitive welfare and UC more broadly, while the majority of Labour voters (in 2017) opposed IWC.

The Conservative government, however, appeared to manipulate perceptions of IWC, including through obfuscation and lowering visibility (e.g. omission from manifestos and emphasising employment support over its punitive dimensions) and, to a lesser extent, ‘justification’ to convince voters of the merits of the reform (Vis, Reference Vis2016: 13), among other strategies. These blame avoidance tactics may appear overly cautious or even counterproductive, especially given that Conservative or Liberal governments are less likely to be punished for retrenchment (Schumacher et al., Reference Schumacher, Vis and van Kersbergen2013).

The Conservative Government’s approach could be intended to mitigate the negative effects of opposition to IWC among Conservative voters with dependent children suggested by our analysis, representing one of the most pronounced divides among voters supporting the same party. Labour and SNP critiques of IWC referencing working families with caring responsibilities therefore appear to be astute. Even still, future research could aim to better understand why Conservative parents are more likely to oppose IWC, which arguments in support of or against IWC shape their preferences, and how, if at all, these inform their decisions at the ballot box.

While Labour and its voters (in 2017) were relatively aligned in opposition to IWC, Labour MPs’ criticisms could both appeal to and alienate its voters. The argument that certain kinds of recipients should not be subject to IWC appeared partly to reinforce notions of distributive deservingness between those ‘working hard’ and other recipients. Framing hard work as including unpaid caring responsibilities may run contrary to Labour’s more solidaristic agenda to develop a less punitive system of social security for all recipients visible in its 2019 election manifesto. Our analysis of IWC preferences, however, pointed to the interpretation of IWC as a more traditional redistributive issue. A broader critique of the Conservative ‘sanctions regime’ could alienate some voters that support some forms of punitive welfare, even if there is evidence of softening attitudes on punitive welfare (Sage, Reference Sage2019: 102).

A broader critique of punitive welfare has clearer advantages for the SNP, whose voters were the most likely to oppose IWC, albeit with a sample size too small to draw strong conclusions. This aligns with the Scottish Government’s recent welfare reforms, following the devolution of some powers to Holyrood, that foregrounded arguments about egalitarian principles in social security (Scottish Government, 2016). Criticising the UK Government on these grounds also provides the SNP with additional ammunition for its broader cause of Scottish independence.

However, our analysis has several limitations. First, the preferences of parties and voters on IWC are not necessarily fixed. For example, the Labour Party, could depart from its more recent commitment to a non-punitive social security system, and public attitudes on punitive welfare and retrenchment could continue to soften, reducing the support for IWC (Sage, Reference Sage2019). Our research into voter preferences at one point in time is not well designed for the important question of the direction of the relationship between party positions and voter preferences on IWC (Sage, Reference Sage2019). Nor can we say whether these attitudes changed as Universal Credit was rolled out to more households and parts of the UK after 2017. The high proportion of ‘Don’t knows’ and the timing of the research suggests the effects of the policy and how these are framed, once fully implemented, could shape preferences further.

Moreover, political parties, their representatives and voters are motivated and influenced by other exogenous and endogenous factors only partly studied here. The economic crisis arising from the COVID-19 pandemic from March 2020 could boost opposition to IWC as more citizens are exposed to Universal Credit. Alternatively, if the tide once again shifts towards austerity in response to challenging economic conditions, IWC could be framed as a key mechanism for reducing unnecessary costs. It will therefore be important to (re)consider the politics of IWC in light of the economic and labour market challenges brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath.

The specific wording of the survey question is also likely to have influenced respondents’ understanding of each proposal (Roosma et al., Reference Roosma, Gelissen and van Oorschot2013; Kootstra and Roosma, Reference Kootstra and Roosma2018) and our decision to reference tax credits is likely to have evoked notions of more ‘deserving’ working recipients. This was deliberate but may have less direct policy relevance in the current context because UC blurs the status of being in- and out-of-work (Dwyer and Wright, Reference Dwyer and Wright2014). This blurring may give the government more space to dictate the narrative around in-work conditionality by appealing to a broader perception of undeserving benefit recipients (e.g. by framing working claimants as ‘underemployed’).

Conclusion

This article contributes new insights into the politics of social policy by applying a framework about welfare state politics, focusing on voter and party preferences, to the study of IWC. It contributes empirical insights through systematic analysis of parliamentary contributions, party manifestos and novel survey data to examine voter and party preferences for IWC in the UK. We find broad partisan alignment on IWC, but also some points of difference that could inform voter behaviour and political parties’ positioning. Namely, the Conservative Party could lose favour among its voters with dependent children for supporting IWC, and the Labour Party’s recent critique of punitive welfare more broadly could alienate some voters that support conduct conditionality in some contexts. Both parties could decide to prioritise their policy-seeking goals and attempt to shape voters’ preferences accordingly. However, we also found evidence of competing policy positions among representatives of the same parties, especially within Labour, and suspect the changing economic and social context could result in changing preferences in the coming years. The politics of IWC are therefore still in motion and remain an important topic for future research.

Acknowledgements

This article uses data from an online survey funded by the Institute for Policy Research, University of Bath, where part of the research was conducted. The research is also partially funded by the Research Council of Norway (Grant Number: 275382). The authors would like to thank attendees of the Welfare Conditionality Conference in York in 2018 and members of the Money, Security and Social Policy Network for their helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article. We are grateful also for the helpful feedback we received from J Millar, N Pearce, W van Oorschot and M Dickson on earlier drafts of the article and G Picot for feedback on the later version. We are very grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions and feedback. The title of this article is a modified version of a blog post presenting an initial analysis of the attitudinal data examined Abbas (Reference Abbas2017).

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746421000294