Introduction

In recent years, comparative criminologists have increasingly used concepts from political science to make sense of the variations in law and order policies throughout Western industrialised countries. Two main arguments have been put forward.Footnote 1 First are those studies that emphasise the important influence of the capitalist political economy in general (Lacey, Reference Lacey2008) and the welfare state in particular (Sutton, Reference Sutton2004; Cavadino and Dignan, Reference Cavadino and Dignan2006, Reference Cavadino, Dignan, Body-Gendrot, Hough, Kerezsi, Lévy and Snacken2014; Downes and Hansen, Reference Downes, Hansen, Armstrong and McAra2006). Cavadino and Dignan (Reference Cavadino and Dignan2006, Reference Cavadino, Dignan, Body-Gendrot, Hough, Kerezsi, Lévy and Snacken2014), for instance, compare imprisonment rates and indicators of penal severity, and find that the penal policies of Western industrialised countries follow the well-known welfare state regimes identified by Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990). Second are those studies that emphasise instead the differences in the architecture of political systems and suggest that such differences can explain why Western industrialised countries differ in terms of their law and order policies. Lappi-Seppälä (Reference Lappi-Seppälä2008), for instance, finds that the type of democracy as developed by Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1999, Reference Lijphart2012) is closely linked to different indicators of law and order and penal severity. The reasons are mainly to be found in the political culture that consensus and majoritarian democracies promote (Pratt, Reference Pratt2008; Savelsberg, Reference Savelsberg and Nelken2011) and the party competition linked to different electoral systems (Newburn, Reference Newburn2007).

Although these studies have to be applauded for pointing out that political and economic characteristics seem to matter for law and order policies, several shortcomings persist in this literature. First, on an empirical level, existing studies often only use one specific indicator, most commonly imprisonment rates, to examine how countries differ with respect to this variable. This is a pity given that concepts like law and order, or punitivity, are multidimensional and can hardly be assessed using only one measure (Matthews, Reference Matthews2005; Frost, Reference Frost2008; Kury and Ferdinand, Reference Kury, Ferdinand, Kury and Ferdinand2011). Second, on a theoretical level, the relationships between regime typologies and the variations in law and order policies have not been established in a convincing way. Most studies restrict themselves to finding empirical patterns without answering the question as to why law and order policies should resemble a certain typology. And if some studies discuss possible explanations for the observable country differences, it is rather unclear how these are related to each other, to the overall regime concept used and to the outcome. Hence, the mechanisms that supposedly create the country clusters are rather vague.Footnote 2

These two shortcomings of the existing literature are the starting point of the present article. We address the existing limitations of the state of the art by investigating: (1) how Western industrialised countries cluster in terms of their law and order policies and (2) whether the country clusters differ in a way that can be associated with comparative political science frameworks. In answering these questions, the present article contributes to the existing literature in three ways. First, by bringing together insights from criminology and political science, we present a theoretical discussion of the relationships that could explain why features of either the political economy or the political system may be related to law and order policies. Second, we use six different variables linked to law and order policies in a broadly defined way, and hierarchical cluster analysis to investigate whether countries cluster in distinct groups. Hence, we move beyond the analysis of imprisonment rates, which has been the standard approach in criminology for years, and use a broader concept of law and order (more on this in the section on research design, operationalisation, data and methods) (for a similar endeavour, see Karstedt, Reference Karstedt2015). We indeed find three different country clusters that resemble more the worlds of welfare capitalism and less the types of democracy. Third, we investigate by means of a linear discriminant analysis in what way the country clusters differ from each other. We find that labour market regulation and the structure of the capitalist system, as well as the professionalisation of the bureaucracy, seem to matter much more than variables linked to the political system or cultural factors.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: the theoretical relationships are discussed in the next section, followed by a section that presents the data, variables and methods. The empirical analysis is to be found in the subsequent section, while the final section discusses the results and concludes.

Theory: why should countries cluster?

The literature dealing with differences and commonalities of law and order policies in Western industrialised countries is mainly criminological and rather young. One of the fathers of the recent literature was, maybe unintentionally, David Garland who suggested that a uniform trend towards harsher policies would occur in the US ‘and elsewhere’ (Garland, Reference Garland1996: 442) – hence in the entire Western world (similarly Pratt, Reference Pratt2007: 94). In reaction to this ‘elsewhere’-hypothesis, more and more studies discovered marked differences between the nation states (Cavadino and Dignan, Reference Cavadino and Dignan2006; Tonry, Reference Tonry2007a), especially in Europe (Snacken, Reference Snacken2010; Snacken and Durmontier, Reference Snacken and Durmontier2012). Thus, the main impetus of the entire strand of the literature was clearly empirical in nature: The aim was to demonstrate real-world variation between countries and to refute the thesis of a general trend towards ever-harsher law and order policies:

As icy trade winds of punitive law and order ideology seemingly sweep the globe, we need to hold fast to the recognition that things can be done differently to the dictates of the current gurus of penal fashion. (Cavadino and Dignan, Reference Cavadino and Dignan2006: 4)

This largely empirical starting point also explains that theoretical accounts of why there should be differences between countries have only been developed at the margin. The existing studies mostly discuss explanatory factors ‘ad hoc’. Again, the influential book of Cavadino and Dignan is a case in point. Although the authors identify different ‘worlds’ of penal systems and refer to the concept of Esping-Andersen, they remain suspiciously silent on the question why these different worlds should have formed and what Esping-Andersen's power resources explanation of the three worlds of welfare capitalism has to do with it. In order to address this theoretical shortcoming, this section will first discuss how major accounts in the criminological literature explain differences in law and order policies. In a second step, we will then ask whether these explanations can be related to the concepts used by comparative criminologists in order to make sense of the cross-country variation – namely Lijphart's differentiation between consensus and majoritarian democracies and Esping-Andersen's typology of different worlds of welfare capitalism.

Criminological explanations

The criminological literature on explanations for law and order policies is rather unsystematic – but there are at least six different approaches that can be distilled from the literature. The crime link is the most obvious explanation for law and order policies as it suggests a functional relationship between the crime rate and law and order policies. The state is said to respond to higher crime rates (Bottoms, Reference Bottoms, Clarkson and Morgan1995; Gottfredson and Hindelang, Reference Gottfredson and Hindelang1979) or the perception of a higher crime rate by the middle class (Garland, Reference Garland2001) by means of tougher law and order policies and increased punishment.

The labour surplus link dates back to the work by Rusche and Kirchheimer (Reference Rusche and Kirchheimer1968) and has been further development since (Jankovic, Reference Jankovic1977; Greenberg, Reference Greenberg1983; Chiricos and Delone, Reference Chiricos and Delone1992). It proposes a direct relationship between the labour market (essentially: unemployment) and the use (and the severity) of penal policies – unrelated to the development of actual crime. Different reasons are held responsible for this (see: Chiricos and Delone, Reference Chiricos and Delone1992), the most prominent being deterrence: ‘Punishment is expected to be more severe during economic crises because the policy of deterrence dictates an intensification of punishment in order to combat the assumed increased temptation to commit crime’ (Jankovic, Reference Jankovic1977: 20). Over time, several siblings of the original approach have been created – arguing that not only unemployment, but also poverty or inequality are responsible for increased imprisonment which is, again, used to deter the poor from committing crimes (Wacquant, Reference Wacquant2009).

The insecurity link suggests that feelings of insecurity among citizens have increased during the last decades because of very different developments such as the emergence of postmodernism and the risk society characterised by profound value change, omnipresence of risk in everyday life, insecurity of labour markets and so forth (Beck, Reference Beck1986, Reference Beck2011; Giddens, Reference Giddens1990; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Giddens and Lash1994; Bauman, Reference Bauman1999). Building on the insight that a substantial transformation of Western societies is occurring, criminologists argue that governments try to counter these very general feelings of insecurity by demonstrating security via law and order policies (Singelnstein and Stolle, Reference Singelnstein and Stolle2012; Mythen, Reference Mythen2014).

The political culture link considers law and order policies to be a consequence of different political cultures: ‘Demand for punishment seems to be highest in societies that have a strong commitment to individualistic means of social achievement’ (Sutton, Reference Sutton2004: 171). According to this approach, the cultures of nation-states and societies differ in terms of some basic values such as solidarity, trust or competition and individual achievement – a difference which is rooted in the historical heritage of these countries (Savelsberg, Reference Savelsberg and Gerhards2000). Scandinavian countries and their penal ‘mildness’ has often be explained by their ‘culture of equality’ (Pratt, Reference Pratt2008) or the importance of values like solidarity and social trust (Lappi-Seppälä Reference Lappi-Seppälä, Body-Gendrot, Hough, Kerezsi, Lévy and Snacken2014: 313). A similar argument has been made for the variations between American states (Newburn, Reference Newburn, Newburn and Morgan2006: 257), building on Elazar's distinction between three types of ‘political culture’ in the US (Elazar, Reference Elazar1966).

The party competition link regards law and order policies as dependent on the dynamics of party competition and electoral systems (Jacobs and Helms, Reference Jacobs and Helms2001; Newburn, Reference Newburn2007; Lacey, Reference Lacey2010, Reference Lacey2011). First-past-the-post electoral systems, which foster fierce partisan competition of two parties (or party blocks), have been found to create a spiral where the two parties compete intensely on law and order issues and move their ideology and their policies gradually in a more repressive direction – a dynamic Lacey has termed ‘prisoner's dilemma’ (Lacey, Reference Lacey2008). A political actor who tries to pursue harsher policies in order to win votes will therefore have a much greater incentive to do so in two-party systems.

Finally, several studies emphasise the impact of professional bureaucracy, i.e. expert civil servants on law and order policies (Savelsberg, Reference Savelsberg1994; Tonry, Reference Tonry and Tonry2007b: 31–2) (bureaucracy link). Countries with a tradition of expert and non-political civil servants are said to exhibit less repressive law and order policies (Garland, Reference Garland2001: 150) because an apolitical bureaucracy may shield the policy-making process from populist tendencies in a law and order context. Savelsberg forcefully argues that one has to account for these different ‘nation-specific institutional structures of knowledge-production’ (Savelsberg, Reference Savelsberg1994: 939) when explaining differences in law and order policies.

Linking political science and criminology

The criminological explanations summarised above can be related to the broad concepts from political science, which focus on the characteristics of political systems or on features of the political economy in order to explain variation in law and order policies. Lijphart's distinction between consensus and majoritarian democracies (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012) has been introduced into the debate by Lappi-Seppälä (Reference Lappi-Seppälä2008: 367) who argues that:

[c]onsensus brings stability and deliberation. Political changes are gradual, not total as in majoritarian systems in which the whole crew changes at one time. In consensus democracies, new governments rarely need to raise their profiles by making spectacular policy changes. Consensus criminal justice policy places value in long-term consistency and incremental change . . . In short, consensus politics lessen controversies, produce less crisis talk, inhibit dramatic turnovers, and sustain long-term consistent policies. Consensus democracies are less susceptible to political populism. (Lappi-Seppälä, Reference Lappi-Seppälä2008: 377)

From the quote, it is obvious that two of the six criminological linkages are rather directly referred to. First, the party competition link is addressed using the argument that majoritarian electoral systems, which produce single party governments and ‘spectacular policy changes’ every time the government changes, are more susceptible to political populism in the realm of law and order. This is very much in line with the argument put forward by Lacey (Reference Lacey2008, Reference Lacey2010: 62–77) or Newburn (Reference Newburn2007) according to which a PR system that creates coalition cabinets and which leads to less intense party competition will successfully dampen self-reinforcing competition regarding ever harsher law and order policies. In contrast, in first past the post systems, which tend to bring about two major parties, fierce partisan competition between the two competitors generates a race to the top in terms of law and order harshness because the two parties outpace each other with a ‘tough on crime’ electoral strategy to win votes.Footnote 3 Second, Lappi-Seppälä also argues that consensus democracies foster a certain political climate characterised by consensus and a culture of trust (Lappi-Seppälä, Reference Lappi-Seppälä2008: 379). This argument resembles the political culture link, which links cultural values such as solidarity to law and order policies and has been used particularly to explain why law and order policies are substantially less repressive in Scandinavian countries (Pratt, Reference Pratt2008)

The second strand of the comparative work on differences in law and order policies emphasises the importance of the political economy. Again, several interconnections between the two most important political science concepts of the political economy – the welfare-capitalism-approach (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990) and the varieties of capitalism framework (Hall and Soskice, Reference Hall and Soskice2001) – and the criminological explanations can be pinned down.

First, the organisation of the welfare state directly affects the labour surplus link. The more de-commodifying the welfare state, the less the degree of inequality and poverty is to be expected. In addition, the commitment to full employment in Scandinavian welfare states should also impede governments from using deterrence strategies such as harsher punishment as proposed by the labour-surplus link. Similarly, the varieties of capitalism approach also points to differences in labour-market regulations between capitalist systems, with coordinated market economies (CMEs) aiming to integrate a maximum number of people into the labour markets by investing in public education, re-training programs, etc. Instead, in liberal market economies (LMEs), prisons have ‘become a mechanism for “warehousing” those excluded from the legitimate economy’ (Lacey, Reference Lacey2012: 14). Second, the welfare state also affects the insecurity link – via de-commodification and stratification. A more generous welfare state should make people feel less insecure because it reduces different risks linked to poverty and loss of income (health, disability, unemployment). Moreover, a conservative-corporatist welfare state, which guarantees the maintenance of status due to class- and status-based social rights (stratification), should also decrease feelings of insecurity. The same is true in CMEs. In sum, for both reasons, the state should have much less reason to resort to harsher law and order policies aimed at creating a feeling of security in more generous welfare states. Finally, as a third mechanism, Lacey argues that the impact of professional bureaucrats on policies varies according to the type of capitalism (Lacey, Reference Lacey2008: 72–7): In LMEs, the impact of professional bureaucrats on public policies is lower with the result that ‘once a professional bureaucracy is undermined, one of the main tools for depoliticising criminal justice is removed’ (Lacey, Reference Lacey2008: 74). In CMEs, in contrast, civil servants have remained in a strong position. These experts are isolated from the political game, which enables them to resist tendencies towards penal populism. Indeed, this strength of professional bureaucracy may relate to overall patterns of strategic coordination present in coordinated political economies, even outside the economic sector. At any rate, this relationship between the structure of the political economy and the strength of a professional bureaucracy relates directly to the bureaucracy link in the criminological literature.

Interestingly, the six criminological explanations of law and order policies are systematically related to the two main explanatory concepts from political science – political economy and political systems (see Table 1). Whereas the welfare state and the structure of the capitalist economy can be linked to law and order policies via the labour market – the feelings of insecurity and the strength of professional bureaucracy – differences in the institutional structure of political systems (e.g. distinguishing between majoritarian and consensus democracies) are said to affect law and order policies via the party competition they generate and the political culture that is present in such systems. Clearly, resemblances between political systems and welfare state regimes exist (Lacey, Reference Lacey2008). Cusack et al. (Reference Cusack, Iversen and Soskice2007) has shown for instance that, historically, the electoral system has affected the development of a certain type of capitalism. Thus, the impact of electoral systems could, in principle, not only work via party competition (political systems) but also via the welfare state. However, since the formation of a certain form of welfare capitalism much time has passed. Countries’ welfare states as well as capitalist regimes have changed tremendously in recent decades (Schneider and Paunescu, Reference Schneider and Paunescu2012; Seeleib-Kaiser, Reference Seeleib-Kaiser2016) and not always in line (or in opposite directions) with the much less dynamic electoral systems. Hence, while not denying resemblances at the start, it seems reasonable to disentangle the two explanatory concepts and the respective links to law and order policies when analysing law and order policies in the beginning of the 2000s.

Table 1 Criminological explanations and political science regime approaches

From this discussion, it is possible to derive hypotheses that can be used to test empirically which of the explanatory concepts – political economy or political systems – is better equipped to explain cross-country variations in law and order policies. Discussing political economy first, we expect that:

-

Hypothesis – political economy 1. Countries with higher unemployment protection, less inequality and poverty have more lenient law and order policies (H-PE-1 – labour surplus link);

-

Hypothesis – political economy 2. Countries with a welfare state characterised by a higher degree of de-commodification and stratification as well as a highly regulated labour market have more lenient law and order policies (H-PE-2 – insecurity link);

-

Hypothesis – political economy 3. Countries with a strong and professional (non-political) bureaucracy have more lenient law and order policies (H-PE-3 – bureaucracy link).

In contrast, the arguments in the literature emphasising the relevance of the characteristics of the political system yield the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis – political solidarity 1. Countries with a political culture of solidarity and trust have more lenient law and order policies (H-PS-1 – political culture link);

-

Hypothesis – political solidarity 2. Countries with a multiparty system and a PR electoral system have more lenient law and order policies (H-PS-2 – party competition link).

Research design, operationalisation, data and methods

The research design follows the twofold goal of this article. In order to answer the first research question, whether countries cluster according to one of the regime concepts, we will conduct a hierarchical cluster analysis based on several indicators linked to law and order policies. The cluster analysis is mainly exploratory in nature and aims at examining differences and commonalities in law and order policies throughout the Western world. Building on these insights, we will then perform a linear discriminant analysis to assess the second research question, namely which variables are responsible for the groupings of the countries.

The cluster analysis is based on a set of six variables, the choice of which follows conceptual reasons. Following Kury and Ferdinand, we distinguish between a judicial and a legal (and, thus, political,) dimension of law and order (Kury and Ferdinand, Reference Kury, Ferdinand, Kury and Ferdinand2011). Given the explanatory model, which focuses much more on the political dynamics of law and order policies, we restrict our conceptualisation to the political dimension, i.e. aspects of law and order policies (legislation, spending, etc.). What indicators, then, represent different aspects of such a political dimension of law and order? Undoubtedly, legislative output would be the most direct way to measure the policy stance of a certain country. However, as comparable data on several countries’ legislation is not available, case studies are, for the moment, the only way to assess the development of legislation in different countries (for England and Wales: Farrall et al., Reference Farrall, Burke and Hay2016; for Germany: Wenzelburger and Staff, Reference Wenzelburger and Staff2016).

Given this restriction, we therefore follow Lowi (Reference Lowi1972) and use six variables that represent the regulative and distributive dimension of law and order policy-making. On the regulative side (e.g. rules governing individual behaviour in penal law), we use three indicators from the ‘democracy barometer’ (Merkel et al., Reference Merkel, Bochsler, Bousbah, Bühlmann, Giebler, Hänni, Heyne, Müller, Ruth and Wessels2014; Wagner and Kneip, Reference Wagner, Kneip and Merkel2015) that capture: (1) the extent to which a country is under the secure rule of law, (2) the degree of inhumane or degrading punishment and (3) the extent to which the freedom of the citizens to exercise and practice their religious beliefs is subject to government restrictions.Footnote 4 The democracy barometer is particularly well suited for capturing the regulatory framework because it sets out to measure the quality of democracy beyond the distinction between democratic and non-democratic countries. Therefore, the data reveal considerable variation between Western industrialised countries (Bühlmann et al., Reference Bühlmann, Merkel, Müller and Weßels2012). The distributive part is approximated by three indicators that reflect government decisions on resources: (1) the number of police officers in a country, (2) the general government expenditures on public order and safety and, finally, (3) the extent of imprisonment.Footnote 5 Again, although interrelated, these indicators reflect different aspects of the distributive dimension. Take government expenditure as an example: Indeed, spending on law and order is affected by the extent of imprisonment and the number of police officers, but it also reflects investment in surveillance techniques (CCTV), data collection etc. The fact that the highest correlation between the three indicators only amounts to 0.37 also indicates that the variables grasp distinct aspects of the distributive dimension.

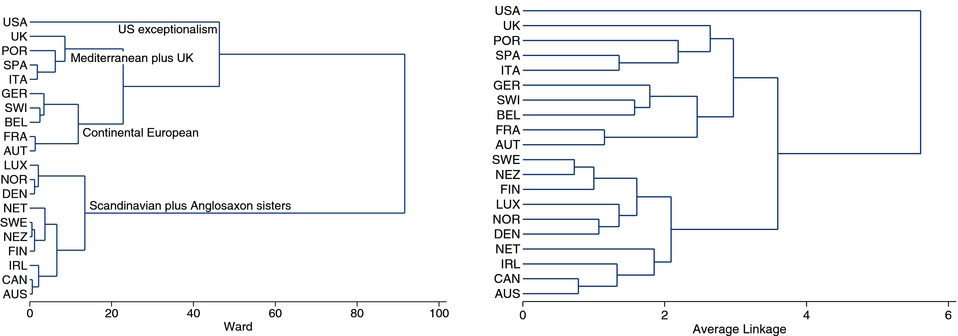

As we are mainly interested in cross-country variance at a very aggregate level, we use arithmetic means for the period 1998 to 2010 for all indicators, which leaves us with twenty observations.Footnote 6 Indeed, looking at temporal variance, too, would be interesting in order to discover the causal relationships that lead to tougher or more lenient policies. However, as the main aim of this article is to grasp cross-country variance, and as the theories reviewed before argue that different levels of law and order policies are to be expected in different types of welfare states or political systems, we restrict the analyses to the theoretically most relevant cross-sectional dimension that is to the differences in levels between the countries.Footnote 7 In terms of the cluster algorithm, we use the Ward method (hierarchical clustering) based on the z-standardised values of the indicators. However, other algorithms (e.g. complete or average linkage) yield similar results. Country clusters are identified via visual inspection of the dendrograms.

Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) is used to see how well the explanatory factors identified above discriminate between the country groups (‘descriptive discriminant analysis’ (Huberty and Olejnik, Reference Huberty and Olejnik2006)). Admittedly, the number of observations is small (N = 20), which is why we include only a few independent variables into one model at a time.Footnote 8 Besides, we will not draw general inferences from our data and restrict ourselves to a description of the patterns found in the twenty countries under observation.Footnote 9 This low-key approach means that some of the assumptions which would be crucial for drawing inferences from a sample to the population do not necessarily need to be met (Berk, Reference Berk2010). For our purposes, it also makes sense on theoretical grounds because the relationships discussed above only refer to the world of Western industrialised countries.

Each hypothesis derived above is represented by at least one independent variable (see online appendix, Table 1). In addition, we include the homicide rate (see ‘crime link’ above) and the unemployment rate to account for the two most prominently discussed drivers of law and order policies. As the discriminant analysis is based on the results of the cross-sectional cluster analysis, we use the means of the independent variables between 1998 and 2010. In the rare case of missing data (e.g. the Gini-coefficient), the means were calculated from less than the entire period.

Clearly, our methodology based on pattern-identification via cluster analysis and the assessment of the relationship between the explanatory variables and the cluster result using LDA cannot be interpreted as a genuine test of causal mechanisms. Instead, our method comes down to what Berk (Reference Berk2010) calls a ‘descriptive regression’, directed at identifying patterns in the data and relationships between explanatory variables and an outcome – in our case law and order policies.

Empirical analysis

Identifying clusters

The first step of the empirical analysis answers the question on whether we see specific country patterns in terms of law and order policies and whether they resemble one of the typologies discussed above. A first impression of the cross-country variance can be obtained by ranking the countries according to the six underlying variables. The US and Spain, for instance, rank among the top four most repressive countries in four of the six categories, whereas Norway is often among the least repressive (five times among the four least repressive). Besides, Germany seems to fulfil the expectation of having a middle-way-profile (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1987, Reference Schmidt2001). Finally, looking at the means, standard deviations and eventual outliers, it is obvious that the extremely high imprisonment rate in the US is a particularity well-known from the literature.

However, from this first look at the data, it is not possible to judge whether the countries under review are systematically similar or dissimilar. Therefore, we have run a number of hierarchical cluster analyses using the six variables. Cluster analyses create groups of countries that are as homogenous as possible and as different as possible from each other. As a result of this process, and independent of the cluster algorithm, we obtain a solution with four clusters (see Figure 1). However, the first cluster is not a country group, but a single nation: the United States.Footnote 10 The fact that the US seem to play a completely exceptional role was already observable in the raw data and the analysis corroborates this impression. The second cluster consists of three Mediterranean countries (Portugal, Spain and Italy) and the UK. Depending on the algorithm, the UK joins this cluster sooner or later. The third cluster unites five Continental European countries, namely Germany, Switzerland and Belgium as well as France and Austria. Finally, the remaining forth cluster is larger and more heterogeneous. It includes the Nordic countries (Sweden, Finland, Norway and Denmark), the four remaining Anglo-Saxon countries in our sample (Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand) as well as the Netherlands and Luxemburg.

Figure 1. Cluster analysis

In order to see in what respects the country groups differ from each other, we have calculated the means of the underlying variables for the three clusters and analysed the variances (excluding the US). The results show significant differencesFootnote 11 between the groups (Figure 2): The Mediterranean cluster (and the UK) is the most repressive on all variables except religious freedom where the countries in the Continental European cluster are more restrictive. At the same time, the Continental European countries have least people incarcerated and rank in a mid-position on all the other four variables. Finally, the Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon countries (without the UK) are the most liberal in all variables except imprisonment where they are joined by the Continental European countries (and outpaced, but only to a small degree).

Figure 2. Cluster characteristics

How well does this result mesh with the well-known typologies from political science? Clearly, the law and order cluster are more similar to welfare capitalist regimes than to types of democracies (see Online Appendix, Table 2). The Mediterranean cluster and the Continental European cluster are very close to welfare regimes as found by Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) or Ferrera (Reference Ferrera1996). Besides, the Nordic countries and the Netherlands (which are, according to Esping-Andersen's original classification, part of the socialist world – Esping-Andersen Reference Esping-Andersen1990: 74), stick together. However, the Liberal world is divided in two groups: one group, the ‘Anglo-Saxon sisters’, i.e. the former colonies of the UK as well as Ireland join the Nordic countries and the Netherlands and form a heterogeneous group; the other two countries of the liberal world, the US and the UK, follow a clearly different path. The UK joins the Mediterranean countries, and the US constitutes an even tougher world of its own. In contrast, Lijphart's concept of consensus and majoritarian does not resemble the law and order clusters to any great extent. Although the Continental European cluster is dominated by consensus democracies, the other two country groups consist of both, consensus and majoritarian democracies.

Explaining clusters

The cluster analysis has shown that the twenty Western industrialised countries under review cluster in three distinct groups with the exception of the United States, which follows its own policy path. However, besides some first guesses, based on interconnections with regime typologies, we do not know whether the country groups are characterised by specificities linked to their political systems or their political economy. It is to this question this section turns. We will report results from the linear discriminant analyses, which relate the hypotheses derived above to the three country clusters. As the number of cases is limited to nineteen,Footnote 12 we have estimated parsimonious models beginning with the two control variables (homicide and unemployment rate), augmenting the models stepwise to a maximum of six independent variables. Table 2 therefore presents four models, including only those variables related to the political economy and representing the three hypotheses from this strand. Models 5 and 6, instead, include variables related to the type of democracy. The two last models (7, 8) finally combine influential indicators in order to maximise the eigenvalue and the classification result while dropping less influential indicators. The robustness of the models has been checked by excluding one country at a time and comparing the classification results. If results vary suspiciously, this is reported in a footnote.

Table 2 Results of linear discriminant analysis

Note: The table displays the standardised canonical coefficients of the variables, the eigenvalue and the canonical correlation of the respective functions as well as the classification results.

The results of the linear discriminant analysis corroborate the impression we already had when interpreting the results of the cluster analysis. The indicators on the political system discriminate rather poorly between the three clusters: neither the party system and the electoral system nor the cultural variable measuring individualism versus collectivism yield a result which separates the three clusters clearly from each other. In contrast, those indicators linked to the political economy yield much better discrimination between the groups. In terms of hypotheses, it seems that all three political economy hypotheses are relevant. The best classification result is reached (Models 7 and 8) if variables relating to the labour surplus link (e.g. generosity of unemployment insurance and level of poverty) are combined with variables representing the insecurity link (e.g. degree of stratification via the social security system) and the bureaucracy link. Model 8 classifies only the UK in the wrong group (in the Scandinavian cluster instead of the Mediterranean cluster), which is not surprising given that the features of the British political economy combine elements of universalism and residualism. Finally, the control variables included in the regressions play a much more marginal role than the indicators representing our theoretically derived hypothesis. The unemployment rate could even be dropped from model 8 without much loss of canonical correlation and classificatory accuracy. The homicide rate, in contrast, does play a certain role – but is less influential than our political economy indicators (such as bureaucracy).

How well do the variables discussed above discriminate between the country clusters? Figure 3 illustrates the results. The graph plots the countries according to the values they take for the two discriminant functions. It is obvious that the two functions discriminate well between the three groups – again, with the exception of the UK, which is put in the midst of the Nordic/Anglo-Saxon cluster. What is more, the graph shows that a good deal of discrimination is already reached with the first function (x-axis), which separates rather clearly the Nordic/Anglo-Saxon cluster from the Mediterranean cluster. The Continental European cluster lies in between these two on function 1. However, the second discriminant function helps us to identify the Continental European cluster as it clearly distinguishes between the Mediterranean and the Continental European countries.

Figure 3. Graphical illustration of the discriminant function scores

In terms of robustness, it seems that the findings are rather robust to the exclusion of individual countries. The canonical correlations as well as the standardised factors only change slightly. For model 7, for instance, the classification result was slightly worse in two cases (three countries classified wrongly), in six cases slightly better (only one false) and when Portugal was excluded, model 7 even classified all remaining 17 countries of the sample in the correct groups. Model 8 was even more stable in terms of classification as there was only one instance where two cases where classified incorrectly (exclusion of Canada) instead of one case. In sum, we therefore think that the results can be interpreted with some confidence even though the number of cases is small.

Conclusion

This article had a twofold goal. First, it aimed at analysing whether Western industrialised countries form distinct clusters in terms of their law and order policy stance while at the same time overcoming the problematic reduction of law and order on a sole indicator, namely imprisonment rate, which characterises the existing literature. The result of our hierarchical cluster analyses based on a set of six indicators is unambiguous. Yes, there are distinct country clusters – three of them and one clear outlier. The clear outlier is the United States which is characterised by the toughest law and order stance and especially by a particularly high imprisonment rate. The Mediterranean countries (Spain, Portugal and Italy) and the UK follow the US in terms of law and order toughness by some distance, and form a first country group. They are on average more repressive than the remaining nations in all but one category (religious freedom). The Continental European countries represent a second cluster which takes a middle position, whereas the Nordic and the Anglo-Saxon countries (without the UK and the US) are the most liberal in terms of law and order (third cluster). In accordance with some comparative criminological studies (Cavadino and Dignan, Reference Cavadino and Dignan2006; Lacey, Reference Lacey2008), this clustering partially resembles existing typologies from comparative political economy research, such as Esping-Andersen's analysis of different worlds of welfare (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990, Reference Esping-Andersen1999). In contrast, influential classifications according to the features of the political system, such as Lijphart's, seem to be much less related to the country clusters.

In order to check these seeming interrelations more systematically, the second goal of this article was to find patterns in the data that point to associations between the characteristics of the typologies and the classification of countries in terms of law and order policies. Based on empirical evidence from linear discriminant analyses, our findings suggest that the characteristics of the political economy – and especially those related to the labour market and the welfare state – seem to be highly relevant for the country clustering, whereas the institutional architecture of the political system seems to matter much less. Besides, the degree of professionalisation of the bureaucracy, which can also be seen as part of the political economy, also helps to discriminate between the three country clusters. To what extent the architecture of political systems and the characteristics of the political economy are, themselves, intertwined is an open question. Indeed, historically electoral systems affected how capitalist systems developed (Cusack et al., Reference Cusack, Iversen and Soskice2007). However, from the results of this analysis, it seems that for law and order policies over the last decade or more, the features of the political economy play an independent role.

These results add to the existing literature in several respects. From a criminological as well as from a social policy perspective, they provide a theoretical and an empirical link between concepts from welfare state research and the classic criminological explanations of penal policies. From a political economy perspective, the article shows that the structure of capitalist systems and welfare states not only affects the directly related economic and social policies, but also more distant policies, in this case the policies of law and order. From the patterns observed in the empirical analysis in this article two ways forward seem to be most exciting. On the one hand, future research could dig deeper into the causal mechanisms that exist between law and order policies and the nature of welfare capitalisms using, for instance, qualitative methods and comparisons of nations. This article has stopped at the level of pattern identification using very aggregate measures and focusing solely on cross-country variance. This is a valid starting point for a policy field that has been almost unexplored, but it would be most valuable to add a temporal perspective, identifying causal mechanisms that lead to restrictive or more lenient law and order policies. On the other hand, it would also be most welcome to look into other policy domains in order to see whether the patterns revealed for law and order policies are also present in neighbouring fields.

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by a grant of the German Research Foundation (DFG) WE 4775/2-1). The author thanks the members of the “brown bag lunch seminar” at the Social Sciences Department of the TU Kaiserslautern and Stefan Wurster for very helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746417000094.