Introduction

Globally, parents and parenting practices are now the central subjects of national and international policy agendas to tackle various domestic social problems and boost international competitiveness (Gillies, Reference Gillies2007, Reference Gillies2008; Faircloth et al., Reference Faircloth, Hoffman and Layne2013b; Daly, Reference Daly2015; Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Roch, Breidenstein and Martin Forsey2020). Alongside changing state and public expectations of parenting practices, various state social policies and programmes are initiated to guide and educate parents about parenting notions and practices as part of wider social welfare systems (Gillies, Reference Gillies and Ritcher2012; Daly, Reference Daly2015). These state interventions into the family realms are seen by some scholars as a form of social governance, or family governance specifically, to produce ideal parents and children under certain socio-political norms and to achieve socio-economic prosperity (Popkewitz, Reference Popkewitz, Bloch, Holmlund, Moqvist and Popkewitz (eds.)2003; Maithreyi and Sriprakash, Reference Maithreyi and Sriprakash2018).

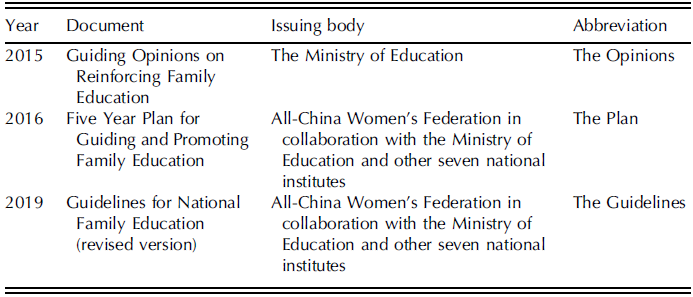

This global attention to parents and parenting practices is also echoed in the post-reform China (after 1978), as is evidenced by a surge of policies and guidelines regarding ‘family education’(家庭教育) Footnote 1 , which can be broadly understood as parenting in general terms. Major family education policies and guidelines include a series of national five-year family education plans, and family education guiding opinions and guidelines. Overall, these documents establish the official frameworks of how Chinese parents should be like and how they should act to foster healthy, successful children. However, so far, they remain to be analysed systematically to understand (1) how the official discourses construct the ideal Chinese parenthood, and (2) what this discursive construction might imply for the contemporary parenting notions and practices, and parent-child relations in China. This article explores these two questions based upon a critical discourse analysis of three recently issued family education documents (Table 1).

Table 1 Family education policies

The analysis shows that the state family education discourses conjoin closely with China’s nation-building agenda embodied in the discourse of suzhi (素质), which can be inadequately translated as quality or population quality. Improving Chinese individual’s suzhi is widely discussed by scholars as a political agenda of nation-building through the creation of ideal citizens who are responsible, rational, and competent (Lin, Reference Lin2017; Rocca, Reference Rocca, Shue and Thornton2017). According to the documents, the ideal Chinese parent is one who embodies high suzhi with awareness of children’s rights and parental responsibilities, and ‘scientific’ parenting skills and knowledge, which, drawing upon international literature, can be understood as a form of family governance based on parental responsibilisation and professionalisation (e.g. Popkewitz, Reference Popkewitz, Bloch, Holmlund, Moqvist and Popkewitz (eds.)2003; Gillies, Reference Gillies2008; Maithreyi and Sriprakash, Reference Maithreyi and Sriprakash2018; Bendixsen and Danielsen, Reference Bendixsen and Danielsen2020; Chiong and Dimmock, Reference Chiong and Dimmock2020).

The article also reflects on the possible implications of the official discourses in three regards. Firstly, the official advocacy for parental responsibilities and children’s rights presages changing yet contested parent-child relations in China, which are traditionally dominated by notions of filial piety and parental authority. Secondly, in order to achieve the parenting ideals based on universal rights/responsibility discourses and modern child development knowledge, structural constraints such as the well-recognised rural-urban inequalities in China (Whyte, Reference Whyte2010) should be taken into account and addressed. Thirdly, the aspirations, endeavours, and agencies of the parents from disadvantaged backgrounds, and the parenting notions and practices among families from diverse socio-cultural backgrounds should be acknowledged and respected. Following these reflections, this article calls for more in-depth empirical studies to understand the implications of the official family education discourses by exploring how they are distributed, received, and reinterpreted by parents in diverse socio-economic and cultural contexts across China.

The parent as a policy concern around the global: support and governance

Around the globe, there is a rising trend of parents and their parenting practices becoming central concerns of national policy agendas to tackle domestic social problems and boost international competitiveness (Gillies, Reference Gillies2007, Reference Gillies2008; Faircloth et al., Reference Faircloth, Hoffman and Layne2013b; Daly, Reference Daly2015; Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Roch, Breidenstein and Martin Forsey2020). Although concerns about child-rearing have deep historical roots in many cultures and countries around the world, in recent few decades, parenting norms are changing and various parenting support, parent education, or family/parent training policies and initiatives have emerged to guide and educate parents about child-rearing (Gillies, Reference Gillies and Ritcher2012; Daly, Reference Daly2015).

On one hand, these social policies and initiatives constitute a form of increasingly institutionalised social welfare policy system. They offer a range of services, including information provision, skill development, and building support networks, to help parents with their parenting practices (e.g. Gillies, Reference Gillies2005; Lewis, Reference Lewis2011; Daly, Reference Daly2015; Lundqvist, Reference Lundqvist2015; Sihvonen, Reference Sihvonen2018). They are also closely linked with other social policy domains, such as, child protection, health, education, and child, youth and family services (Daly, Reference Daly2015).

On the other hand, these policies and initiatives are seen as a mechanism of social governance (or family governance, specifically) with deep social and political imprints and implications (Popkewitz, Reference Popkewitz, Bloch, Holmlund, Moqvist and Popkewitz (eds.)2003; Maithreyi and Sriprakash, Reference Maithreyi and Sriprakash2018). They problematise traditional parenting practices and aim to transform parenthood, and parent-child and family-state relations in alignment with changing national and global social, cultural, and political expectations (Faircloth et al., Reference Faircloth, Hoffman, Layne, Faircloth, Hoffman and Layne2013a).

Tracing the historically shifting discourses about ‘the parent’ in Euro-American countries, Popkewitz (Reference Popkewitz, Bloch, Holmlund, Moqvist and Popkewitz (eds.)2003) argues that since the Enlightenment age, parents have been increasingly constrained by formal responsibilities for children’s development and civilisation, and ‘the family’ has been the subject of governance as family relations and aspirations are seen as instruments to govern populations. As Shamir (Reference Shamir2008: 6) put it, responsibilisation is ‘an ‘enabling praxis’ and a ‘technique of government’ and ‘responsibility is the practical master-key of governance’. State policies and programmes focusing on parenting practices are ‘the inscription device of governing’ which ‘maps the interior of the parents’ or their ‘system of reason’ … ‘to render them visible and amenable to government’ (Popkewitz, Reference Popkewitz, Bloch, Holmlund, Moqvist and Popkewitz (eds.)2003: 36). Now, parents in Western countries are at the centre of neoliberal governance to create law-abiding, responsible individuals, families, and communities (Vincent, Reference Vincent1996, Reference Vincent2017; Popkewitz, Reference Popkewitz, Bloch, Holmlund, Moqvist and Popkewitz (eds.)2003; Gillies, Reference Gillies and Ritcher2012; Dehli, Reference Dehli2017). The process of parental responsibilisation has also been explored in contexts such as India (Maithreyi and Sriprakash, Reference Maithreyi and Sriprakash2018) or Singapore (Chiong and Dimmock, Reference Chiong and Dimmock2020). Overall, it is underpinned by a notion of ‘parental determinism’ that all forms of parental values and behaviour are directly and causally associated with child’s development (Lee and Bristow, Reference Lee and Bristow2014; Widding, Reference Widding2018). The mechanism of parental responsibilisation in these national contexts are critiqued for privatising parenting and individualising parents for their duties to ensure children’s success in education and life under neoliberal, market-oriented logics.

Furthermore, parents are subjected to a process of professionalisation as parenting has been increasingly professionalised as a job which requires particular expertise and skills (Gillies, Reference Gillies2005, Reference Gillies and Ritcher2012; Widding, Reference Widding2018). Child development science became the self-evident truth for parents to learn to become a good parent (Bloch and Popkewitz, Reference Bloch, Popkewitz and Soto2000; Popkewitz, Reference Popkewitz, Bloch, Holmlund, Moqvist and Popkewitz (eds.)2003). New professions and professionals including development scientists and teachers became the expert authorities of child rearing, and new organisations such as Parent Teacher Associations were established to spread the norms of development (Bloch and Popkewitz, Reference Bloch, Popkewitz and Soto2000). Parental advice is readily available in various forms of medium to guide parenting practices (Proctor and Weaver, Reference Proctor and Weaver2020). Parents’ involvement in school education is equally, if not more, stressed in policy discourses around the world, with the consensus that it will positively impact school education (Jeynes, Reference Jeynes2010; Epstein, Reference Epstein2011). Those policy frameworks of parental involvement resembled teaching manuals and the parent is expected to become ‘a surrogate teacher’ who advances ‘the political will and progress of the nation’ by fostering ideal children in alignment with school and state visions (Popkewitz, Reference Popkewitz, Bloch, Holmlund, Moqvist and Popkewitz (eds.)2003: 37).

By inscribing social norms of reason, progress, science, and responsibility, changing yet connected discourses of parenthood from the eighteenth century to the turn of the twenty-first century ‘made possible the conditions of the modern state, its citizens, and the pedagogy’ through ‘rationally ordered life of the child and family’ (Popkewitz, Reference Popkewitz, Bloch, Holmlund, Moqvist and Popkewitz (eds.)2003: 36). In a nutshell, these policies and initiatives constitute a state governing mechanism or a form of family governance to enlist parents to become actively responsible citizens, by establishing rules and norms about how parents should and should not act, and could and could not act in their parenting practices. Ultimately, attempts to govern parents extends to governance of children as their parents are guided to produce ideal future citizens.

‘Family education’ policies and family governance in the post-reform China

This trend of increasing prominence of parents in national policies around the globe is also echoed in China by the rising number of ‘family education’ policies and guidelines since the 1990s. Official family education documents include five national five-year family-education plans issued in 1996, 2002, 2006, 2012, and 2016 respectively, two national family education guidelines, issued in 2010 and 2019, and the family education guiding opinions issued in 2015. They establish the official frameworks of how Chinese parents should secure their children’s healthy growth and success in schooling and life.

Social governance in the People’s Republic of China has gone through radical transformations since its establishment. On one hand, it is shaped by state paternalism under Confucian ethics of good governance (Sigley, Reference Sigley2006), central to which is moral persuasion to edify its citizens (Jacques, Reference Jacques2012). Institution of paternalism as good governance has also been reinforced by the contemporary Chinese state through its calls for ruling not just by law but also through morality and moral education (Fairbrother, Reference Fairbrother, Kennedy, Fairbrother and Zhao2014). On the other hand, whereas the pre-reform China (1949-1978) ‘operated almost entirely through official organs and agencies in a hierarchical and highly regulated system of formal authority’ (Bray and Jeffreys, Reference Bray, Jeffreys, Bray and Jeffreys2016: 2), the post-reform China has witnessed significant shifts in its mode of social governance from direct to indirect forms of state regulation, which devolve state functions to local society and stress personal responsibility (Sigley, Reference Sigley2006; Jeffreys and Sigley, Reference Jeffreys, Sigley and Jeffreys2009; Greenhalgh, Reference Greenhalgh2010).

Accordingly, since the 1950s, family-state relations in China have gone through radical changes as families face various revolutionary and socio-economic reforms such as ‘people’s commune system’ in the pre-reform era, under which families were organised into collectivised agricultural production teams, and the privatising ‘household responsibility system’ under which the household becomes the basic unit of production (Huang, Reference Huang1976). These changing family-state relations in China have been discussed from many perspectives. For instance, in their studies of the one-child policy, Greenhalgh and Winckler (Reference Greenhalgh and Winckler2005: 2) argue that the policy, underpinned by state concerns about ‘the size and ‘backwardness’ of China’s population’ and a strong state will to control the population quantity while improving its suzhi (see later) has had an enormous impact on remaking state-family relations. Governing families and individuals in alignment with the wider fields of science and technology, health, population, social policy, as well as Chinese socio-cultural norms and values, the policy was an important instrument to expand state governing capacity, innovate techniques of social governance, produce new subjects for the modern state, and optimise China’s nation-building project to become a strong nation and a global power (Greenhalgh, Reference Greenhalgh2010).

As is argued in international debates, beyond a form of social policy to support parents in their child-rearing practices, relevant policies constitute a mechanism of family governance with deep implications for changing parenting notions and practices, and parent-child relations in Western countries. Based on these insights, this article will analyse three recently issued major, national-level family education documents in China. In the next section, I elaborate on my research materials and methods.

Research materials and analytical methods

Official texts for analysis

Policy represents ‘the authoritative allocation of values for the whole society’ (Easton, Reference Easton1953: 54) and can appear in diverse forms including ‘both text and action, words and deeds, what is enacted as well as what is intended’ (Ball, Reference Ball1994: 10). Policy texts are taken as the focus of this study because they are a powerful ‘vehicle or medium for carrying and transmitting a policy message’ (Kenway, Reference Kenway1990: 59; Ozga, Reference Ozga2000). As ‘the crystallization of authoritative norms’ (Greenhalgh, Reference Greenhalgh2008: 8), they are also the ‘fundamental elements of modern power and instruments of modern governance’ (7). I focus on three latest family education documents, including the family education guiding opinions issued in 2015, the national five-year family-education plans issued in 2016, and national family education guidelines issued in 2019 (Table 1).

I focus on these three documents because while having different focuses, they represent the latest official discourses of family education in China. The Opinions stresses the overarching rationales and objectives of the state family education support and guidance; The Plan, as the latest five-year plan for the ‘family education work’, outlines the blueprints for various social institutions, such as schools, children’s activity centres, or maternal and child health care centres, to provide and expand access to family education information and guidance to support parents in their parenting practices, and The Guidelines offers a detailed account of how parents should foster children, with particular reference to child development knowledge. All three documents can be accessed online.

Critical discourse analysis

I adapt Fairclough’s critical discourse analysis (CDA) approach to examine how the official family education discourses construct the ideal Chinese parenthood and reflect on its implications. Many scholars have used CDA in education policy analysis in various contexts, including the Chinese context (Koh and Zhuang, Reference Koh and Zhuang2021).

Discourse is defined in various ways from different theoretical and disciplinary perspectives. For Fairclough (Reference Fairclough1992, 62), it could narrowly ‘refer to spoken or written language use’. Meanwhile, it is also a form of social practice which is embedded in and constitutive of wider ‘social elements such as power relations, ideologies, economic and political strategies and policies’ (Fairclough, Reference Fairclough2013, Reference Fairclough2015: 5). Thus, ‘[d]iscourse is a practice not just of representing the world, but of signifying the world, constituting and constructing the world’ (Fairclough, Reference Fairclough1992: 64). Or, in other words, discourses both reflect and shape beliefs, values, and social relations, and the social conditions in which they are situated (Allan, Reference Allan2008).

In this article, the three official texts are analysed as a form of official discourses which are not only representative but also constitutive and constructive of the ideal Chinese parenthood, parenting notions and practices, and parent-child relations. Although constantly socially constructed, a discourse ‘stabilizes over time to produce the effect of boundary, fixity and surface’ (Butler, Reference Butler1993: 9). They represent ‘the temporary settlements between diverse, competing and unequal forces within a society and between discursive regimes’ (Kenway, Reference Kenway1990: 59). Therefore, this article understands the family education texts in China as relatively stable state discourses located within, produced through, and constitutive of broader social conditions and relations (Ball, Reference Ball2006; Fairclough, Reference Fairclough2015).

While Fairclough (Reference Fairclough1992) established a three-dimensional conception of discourse based upon text, discursive practice (production, distribution, consumption of the text), and social practice (power relations and ideologies underlying the text), this article uses an adapted approach of Fairclough’s CDA method by focusing only on the two dimensions: text and social practices, while more empirical research needs to be conducted to analyse the other dimension, the discursive practices of family education discourses. Beyond an analysis of discourses, CDA also aims to critically explain, dismantle, and ultimately change the existing social realities which produce and perpetuate social inequalities (Fairclough, Reference Fairclough2015). This echoes the ultimate goal of this article to reflect on and invite more empirical research to examine the implications of the official family education discourses for families from different socio-economic and cultural backgrounds to avoid marginalisation.

Specifically, I followed two analytical steps of description and explanation proposed by Fairclough (Reference Fairclough2015). The description stage is to focus on semantic and grammatical features of textual materials. At this stage, I reviewed three documents identifying words, phrases, and sentences that define how parents should do and should be like to become good parents following a thematic analysis mode. The documents in original Chinese language are read repetitively to discover and code themes related to the notion of ideal parenthood, and thematic patterns are established (Bernard and Ryan, Reference Bernard and Ryan2010). The explanation stage is to explore in-depth how the textual elements constitute and are constituted by wider social practices, and ‘the interstitial spaces between mediated discourses surrounding the text(s) and dominant ideologies.’ (Küçükakın and Engin-Demir, Reference Küçükakın and Engin-Demir2021: 6). This is the core stage of my analysis as it is the ultimate goal of my article to examine how ideal Chinese parenthood is constructed as a form of family governance and part of nation-building project. Original materials in Chinese language are translated into English by myself during the writing process. My mastery of Chinese language, contextual understandings of China, previous educational and professional backgrounds in English-Chinese language translation, and my academic training make me qualified for the translation.

Analysis of the official documents

The ideal parenthood and family governance

The image of the good parent was no longer the technocratic manager engaged in the task of improving and perfecting a child. Instead, the parent was to become a subject of ethics, engaged in the task of governing and improving oneself.

(Kuan, Reference Kuan2015: 11)Analysis shows that family education is emphasised across the three documents as crucial for both children and the nation. For instance, The Opinions states, ‘how family education is carried out concerns children’s lifelong development, … and the future of the country and its people’, which is followed by calls throughout the document for parents to improve their suzhi to conduct good parenting. The Guidelines further repeats the importance of parents’ suzhi. Therefore, according to the official family education discourses, a high suzhi parent is the ideal Chinese parent to successfully foster children and contribute to the national development. Often inadequately translated as ‘quality’ or ‘population quality’, suzhi has its origins in ancient Confucian beliefs ‘that each individual is malleable, trainable and obliged to self-cultivate’, (Murphy, Reference Murphy2004: 2). In the nineteenth century when China encountered colonial powers, its intellectuals concluded that the nation would survive only when the suzhi of each citizen was improved (ibid). Since then, the Chinese society has gone through a deep and complex movement to improve the suzhi of its populace by making them more responsible and educated to build a strong China (Lin, Reference Lin2017; Rocca, Reference Rocca, Shue and Thornton2017). Therefore, the construction of the high suzhi, ideal parent in the family education policy texts is deeply implicated in wider socio-cultural and political projects of China’s nation-building project. Underlying the ‘improving parental suzhi’ discourses is the notion of parenting as ‘an educational project’ for the parent (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim, Reference Beck and Beck-Gernsheim1995: 139), through which parenting can be taught, learnt and improved. In the policy texts, successful family education depends on high suzhi parents who learn to take on responsibilities to prioritise children’s rights and needs, and learn the scientific parenting knowledge and skills to nurture children. Or in other word, main methods to improve parental suzhi include raising their awareness of children’s rights and parental responsibilities, and educating them about ‘scientific’ child-rearing knowledge and skills. Thus, I argue that these official discourses constitute a form of family governance by responsibilising and professionalising Chinese parents in the name of improving their suzhi. In the following discussions, I will elaborate on these mechanisms.

Responsibilisation of the parent

Across the three official texts, while family education is to be supported by the state, local governments, communities, schools, teachers, academics, and, even, the market, parents are held to be the most crucial actors for successful family education. Thus, the official family education discourses constitute a form of parental responsibilisation through raising parental awareness of their moral and legal responsibilities for children.

For instance, in the section titled, ‘To further clarify parents’ position as the main subject of family education responsibilities’, The Opinions states that ‘educating children is a legal responsibility for parents; … [families] shall persistently be child-centred; …[Parents] should respect children’s needs and individuality, and provide child-friendly living conditions and environments.’ Both The Plan and The Guidelines also emphasise parents’ role as ‘the main body of family education responsibility’ (家庭教育主体责任). Parental responsibilities set out across the three texts include, but are not limited to, provision of ‘healthy’ family environment, protecting children from harm and abuse, protecting children’s mental health, teaching children life skills, cultivating children’s morality, supporting children’s all-around development, receiving parenting education, ensuring compulsory nine-year school enrolment and attendance, and cooperating with schools and other educational institutions to improve children’s learning outcomes.

Children’s rights as a universal discourse has been particularly mobilised as an important legal framework to define various parental responsibilities. For instance, The Guidelines reinforces that families shall respect children as an independent subject with ‘rights to life, health, basic living standards, full physical and intellectual development, protection against discrimination, abuse, and ignorance …, participation in family and social life, and expression of opinions’. It also mandates relevant institutions to ‘guide parents to live with children on equal terms, understand children’s wills, and protect children’s rights to privacy’.

Since China became a signatory nation of the UN Convention on Children’s Rights in 1992, children’s rights have been increasingly stressed in official documents (epitomised by the three ten-year national children’s development guidelines) and have gradually entered everyday discourses in China, particularly among urban middle class parents. For instance, Naftali’s (Reference Naftali2014: 124) observes that in Shanghai, discourses of children’s rights seem to have been well-accepted among Chinese urban middle-class families as ‘a highly desirable global, middle-class’ marker as well-educated urban parents show greater respect for children’s opinions, and privacy, and resist using physical punishment to discipline children. Kuan (Reference Kuan2015: 6) also finds that middle class parents in Kunming City increasingly upheld the idea that ‘children ought to be respected as autonomous subjects who have a right to self-determination’.

Beyond responsibilising parents to ensure children’s healthy growth and to respect their rights, great emphasis has been placed upon parental responsibilities for children’s moral cultivation, echoing the pervasive moral edification of Confucian, paternalist governance. For instance, The Plan states that one of the family education objectives is to ‘foster children’s good character and healthy personality’. Parenting to teach children traditional moral values is predominantly stressed in all three documents. For instance, The Opinions advocated for carrying forward the outstanding virtues of traditional Chinese families. The Plan also placed particular emphasis on the promotion of excellent traditional Chinese culture and family virtues which would guide parents and children to learn notions such as patriotism, honesty, filial piety, frugality, and neighbourhood solidarity. The Guidelines further underlines that the significance of parental influence for the formation of children’s ‘behaviour, ideology and morality, and values’ and calls for parents to ‘behave with civility, have healthy tastes, be dedicated and enterprising, consistent in words and deeds, and good at learning and thinking, and consciously practice socialist core values and influence children with healthy thoughts and good moral education’. It particularly hails ‘the parent’ as ‘the first teacher’ responsible for teaching children ‘how to act human’ (如何做人), which is a central idea in Confucian moral education, meaning ‘the making of a moral person’ (Xu, Reference Xu2017: 189).

As the ancient proverb, it is the father’s fault that a child is not educated (子不教, 父之过) demonstrates, the attribution of weighty responsibilities of child-rearing to parents is not new in Chinese history. However, the extent of parental responsibilisation, both morally and legally, in the post-reform China is unprecedented. It increasingly functions as ‘an enabling praxis’ or a ‘practical master-key’ (Shamir, Reference Shamir2008: 6) of family governance by endowing moral agency to Chinese parents to be actively responsible for children’s failure and success.

However, as the analysis so far manifests, there is an absence of market-oriented, neoliberal logics in the Chinese official discourses of parental responsibilisation, which is different from what previous scholars observed and critiqued in the social practices of neoliberal responsibilisation of parents in other national contexts. However, it does not mean that Chinese parenting in practice is not shaped by neoliberalism, which is a highly contested topic itself in the Chinese context (Weber, Reference Weber2020). For instance, as Crabb (Reference Crabb2010) shows, Chinese urban middle class families’ parenting practices are strongly shaped by consumerist dynamics and neoliberal discourses. This invites more empirical research to understand the nuanced dynamics of Chinese state-family relations embedded in complex entanglements between the official discourses and market forces.

Professionalisation of the parent

Family education discourses in China also constitute a process of professionalisation of parenting, as they uphold modern expert knowledge about childhood based on health and psychological theories as the authoritative knowledge for parents to learn in order to become scientifically-informed parents. Both The Opinions and The Plan mandate that parents shall ‘comprehensively learn family education knowledge and systematically grasp scientific family education notions and methods’. The Opinions further calls for parents to be timely in learning about development features of children at different ages. In response, The Guidelines offers a comprehensive list of parenting guidance based on child development knowledge for newly-wed couples, parents-to-be, and parents with children at different age cohorts (including those of from birth to three, from three to six, from six to twelfth, from twelfth to fifteenth, and from fifteenth to eighteenth years old) to improve their ‘capacity to scientifically conduct family education’.

Based on paediatrics and child development theories, the parenting guidance in The Guidelines included more than thirty items of instructions on topics ranging from premarital screening, pregnancy test, natural birth, breast feeding, children’s emotional, cognitive, and communication skills, teaching children digital skills, to sex education. Thus, contemporary parenting in China is officially framed as a practice in need of particular knowledge and skills to be conducted successfully. Modern health and child development knowledge is portrayed as a necessary resource which parents must have access to and learn, in order to become high suzhi, ‘professional’ parents who could fulfil their duty as qualified parents.

Moreover, The Plan calls for family education theories with Chinese characteristics. It stresses that family education shall be established as a research field, that family education research centres be established in cooperation with universities and research centres, and that important family education research projects shall be supported by both national and local social science funding. Universities are also called upon to produce family education materials and establish family education learning programmes. Although no elaboration is made as to what family education theories with Chinese characteristics mean and there is a notion that good parenting can be achieved based on detached, universal modern science, it shows the state wills to localise family education discourses and practices in China.

Implicit in this process of professionalisation are technocracy and scientism that underlie social governance in modern China. While technocracy and scientism were largely decimated during the pre-reform era when policies were based more on political and ideological grounds, the post-reform era has witnessed their rise as fundamental to its social governance and policy instruments: modern science and expert knowledge was enthusiastically embraced by the Chinese government as a panacea to solve many social issues and achieve national modernisation in China (cf. Greenhalgh and Winckler, Reference Greenhalgh and Winckler2005; Greenhalgh, Reference Greenhalgh2008). In the official family education discourses, technocracy and scientism function as mechanisms of family governance by establishing universally sanctioned, scientific norms for parents to learn and follow.

Discussion and conclusion

Based on international literature on policies and state interventions that aim to guide and educate parents about child-rearing notions and practices, this article analyses three recently issued national family education documents in China to examine what the ideal Chinese parent is like in official discourses and reflect on their potential implications. The critical discourse analysis of the documents shows that the official family education discourses in China construct the ideal Chinese parent as one with high suzhi, but with features resonant with observations in the international contexts: responsibilisation and professionalisation of parents. Whereas largely based upon universal discourses of children’s rights and traditions of Confucian moral edification, responsibilisation of parents in the Chinese context is different from that of other national contexts underpinned by neoliberal logics, but it still functions as a powerful mechanism of family governance.

Parenting notions and practices and parent-child relations once belonging to the realms of private are being increasingly penetrated by the state governance mechanisms. Beyond acting as a provider of family education support and guidance, the state acts as an enabler who responsibilises and professionalises parents to be high suzhi parents who could fulfil their parenting duties and contribute to China’s nation-building project. The analysis also shows that mechanisms of family governance through responsibilisation and professionalisation in China are shaped by a pragmatic mix of universal (west-originated) notions of children’s rights, traditional mode of governance through moral edification, technocracy, and scientism.

Meanwhile, the official discourses carry deep implications for parent-child relations and parenting notions and practices in diverse socio-cultural contexts in China. Firstly, while traditional moral and familial values are stressed in all three official documents, the ideals of children’s rights and child-centredness are at the centre of the official discourses and divergent from dominant forms of traditional Han Chinese parent-child relations, which are fundamentally shaped by parental authority, patriarchy, and social norms of filial piety (Ho, Reference Ho and Bond1996; Goh, Reference Goh2011). This presages changing yet contested parent-child relations in contemporary China, which has also been empirically observed by some scholars in urban contexts (cf. Naftali, Reference Naftali2010, Reference Naftali2014; Kuan, Reference Kuan2015).

Secondly, in reference to the international literature (Lareau, Reference Lareau2003; Ball, Reference Ball2006; Vincent, Reference Vincent2017), the urban middle class parents are more inclined to become the ideal parent as they are equipped with educational and socio-economic resources to conduct parenting practices promoted by the state discourses. In contrast, due to their lack of resources and capacities, parents from poor, rural backgrounds in China might be seen in need of particular policy interventions in their parenting capacities and practices, and stigmatised as less responsible and competent. In order to achieve the progressive parenting practices advocated in the official documents, the structural challenges such as the well-recognised rural-urban inequalities in China (Whyte, Reference Whyte2010) should be taken into account and addressed.

Thirdly, the aspirations, endeavours, and agencies of parents from disadvantaged backgrounds, and the parenting notions and practices among families from diverse socio-cultural backgrounds should be acknowledged and respected. To achieve these goals, more in-depth empirical studies should be conducted to understand the implications of the official family education discourses by exploring how they are distributed, received, and reinterpreted by parents in diverse socio-economic and cultural contexts across China.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Arathi Sriprakash and Professor Liz Jackson for their guidance. My special thanks go to the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback and comments.