Introduction

Many European countries struggle with the challenge of sustaining and modifying support for those in old age (OECD, 2008, 2019). Russia and Hungary have two of the most rapidly ageing and shrinking populations globally. Like many countries, they have pursued a combination of structural and parametric pension reforms. Despite similar demographic and fiscal pressures and a shared Communist legacy, why have Russia and Hungary taken different paths in pursuing similar reforms? We argue that differences in their regime types play a central and surprising role in their divergent pension reforms.

We examine why Hungary and Russia differed on two important types of potentially cost-cutting pension reforms: raising the retirement age; and a structural reform often called pension privatisation. This allows us to examine a high salience issue (raising the retirement age) receiving much popular attention and a much lower salience issue (pension privatisation and its reversal) of which much of the public is unaware. Hungary as the more democratic country introduced an unpopular reform (raising the retirement age) sooner and reversed another pension reform (partial privatisation) more quickly. Russia, by contrast, as an authoritarian country did not raise the retirement age until after Putin’s fourth election in 2018 and reversed pension privatisation much more slowly than Hungary. We argue that regime type is a major factor affecting differences in the degree and speed of reform in the two cases, but not for the reasons we usually think. Democracies are often thought to move slower on policy and be more constrained in adopting economically necessary, but unpopular, reforms. In this case, we find that Hungary as the more democratic country was more flexible and able to pursue potentially unpopular reforms.

This article is organised as follows. We first discuss why the variation in outcomes in pension reform in Hungary and Russia is not easily explained by existing explanations, especially those based in explanations of market-oriented reforms in post-communist countries. Next, we consider how differences in regime type between Hungary and Russia explain the differences in their policy outcome. We then compare the cases of Hungary and Russia, addressing the outcomes of raising the retirement age and reversing pension privatisation. Finally, we conclude by emphasising the lessons we can draw from these two case comparisons.

Why this variation is puzzling: European pension reform and policymaking

Pension reform is a pressing and contentious issue for almost every developed country including in European countries. Two potentially cost-cutting measures that are especially relevant in recent times are raising the retirement age and pension privatisation (Müller, Reference Müller, Arza and Kohli2008; OECD, 2019). Raising the retirement age shortens the period of time governments have to support citizens in retirement and is typically phased in over time because it is unpopular.

Pension privatisation entails allocating mandatory retirement contributions to individual accounts that are privately managed and invested so as to shift the burden of paying for benefits from the state to individuals.Footnote 1 Pension privatisation is a system based on defined contributions, rather than the state promising to provide a guaranteed benefit upon retirement. The degree of pension privatisation varies with countries allocating anywhere from all contributions to a relatively small portion of contributions to individual accounts. The privatised portion relies on defined contributions, rather than defined benefits that guarantee a certain level of income. Although many post-communist countries adopted pension privatisation, since 2010 many have also backtracked or abandoned this reform. We choose to focus on the reversal of pension privatisation due to space considerations and for more substantive reasons. Because the reversal trend was more recent and heavily concentrated in post-communist countries, it is in part a continuation of the pressures and political battles that led to its adoption.

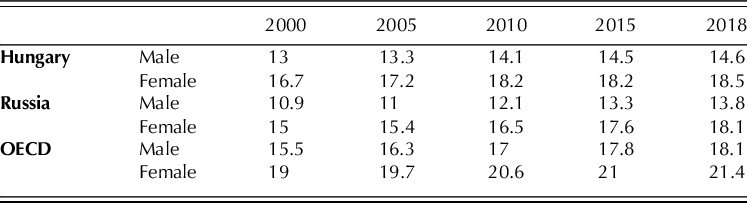

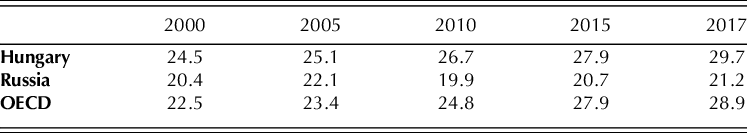

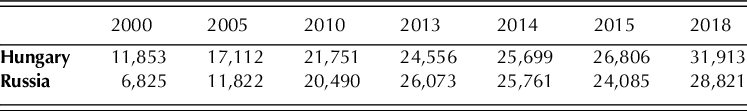

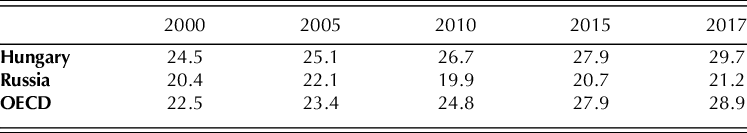

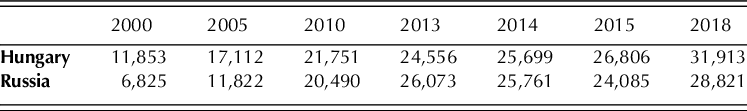

Hungary and Russia had similar demographic situations in that both have faced ageing and shrinking populations in the post-communist period. The tables below demonstrate the striking similarities in the demographic and economic situations in both countries in the 2000s which, in turn, influenced fiscal pressures to cut pension spending and obligations. Table 1 shows that Hungarian retirees live slightly longer than Russian retirees, but not by much. Table 2 presents the old-age dependency ratio which is the ratio of people over the age of sixty-five to the sixteen to sixty-four-year-old population. Higher values reflect an older population. Hungary’s population is older than Russia’s and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average. Finally, at the age of sixty-five Hungarians are expected to live about as long as Russians. Hungary is a slightly wealthier country than Russia by GDP per capita (see Table 3).

The two countries both faced fiscal pressures stemming from expensive pension costs. Hungary ran a significant deficit in the post-communist era which reached 9.26 per cent of GDP in 2006. The deficit shrunk to 3.78 per cent of GDP in 2008. This was due to new economic policies including measures to increase the liquidity of financial institutions, increase taxes, and cut spending on social benefits (Benczes, Reference Benczes2009). Despite these deficit cutting measures, the new Fidesz government elected in 2006 still faced significant debt (OECD). Footnote 2 By 2011, Russia enjoyed a government surplus from 2002-2008, but had a deficit in 2009 and 2010 as a result of the global financial crisis. By 2011, Russia’s surplus was back to about 3 per cent of its GDP (OECD and World Bank). Despite this surplus, Russia still had increasing fiscal concerns. The Russian government weathered the 2009 global financial crisis in part by spending down its significant financial reserves funded by oil and gas revenues which left it with a much smaller fiscal buffer (Gaddy and Ickes, Reference Gaddy and Ickes2010).

Critically, in the post-communist era both countries have faced ageing populations with projections of increasing annual pension costs (OECD, 2019). On top of this, the annual cost of sustaining pension privatisation in each country was worth several percentage points of GDP. Hungary faced the additional pressure of staying with the deficit guidelines required by the EU which refused to make an exception for Hungary due to its pension reforms despite the government’s request. Footnote 3 Hungary was estimated to lose 1.4-2.2 per cent of GDP per year for forty-three years as part of its transition to pension privatisation (Fultz, Reference Fultz2012; Orenstein, Reference Orenstein2013). By backtracking on pension privatisation, it was estimated that the Hungarian government could gain $14.2 billion in revenue in the short term. Footnote 4 The Russian government’s reversal has been estimated to have been worth about $58 billion in immediate revenue. This was enough to nearly cover Russia’s total Pension Fund debt of $50 billion in the short term. Indeed, the Russia’s Pension Fund debt declined to almost nothing in 2013 after its reversal only to shoot up in subsequent years. Footnote 5

In short, both countries faced significant fiscal pressures – albeit in different ways – and expensive pension systems. Given their similar situations, we might have expected both countries to have pursued pension reforms in similar ways. In reality, however, they took very different reform paths. The countries differed in their pension policies including how quickly and to what extent they raised the retirement age and adopted and reversed privatised pensions. Russia and Hungary adopted and reversed pension privatisation largely because of fiscal pressures, but Hungary made its changes earlier and more quickly due to its pro-market reform period in the 1990s and a greater focus on a populist strategy that did not rely on pension policy. Next, we explain how regime type explains the divergent trajectories in Russia and Hungary during the post-communist period.

The effect of regime type: explaining the divergent Hungarian and Russian trajectories

A major difference between Hungary and Russia in the 1990s and early 2000s is the type of political regime. When Hungary embarked on pension reforms in the 1990s and early 2000s, it was a competitive democracy with strong protections of civil and political liberties (Zamecki and Glied, Reference Zamecki and Glied2020). In 2010, Fidesz won a super majority in the legislature and Viktor Orban and the Fidesz party began to consolidate power and erode democratic institutions including a free and open media and an independent judiciary (Grzymala-Busse, Reference Grzymala-Busse2019). Russia in the 1990s was somewhat democratic, but did not have stable political parties and President Boris Yeltsin never enjoyed a legislative majority. When Putin assumed the role of acting president in January 2000, he ushered in a period of increasing authoritarianism.

Existing work suggests two competing hypotheses for the effect of regime type on market-oriented economic reforms including pension reforms. One expectation is that democratic countries will be worse at pursuing necessary economic reforms in a consistent manner. The initial thought was that democratic countries might be less likely to pursue painful but necessary economic reforms because of the J-curve argument described by Przeworski (Reference Przeworski1991). According to the J-curve explanation, economic reforms would mean things got worse before they got better and the electoral timeframes are too short for the uncertain and longer term payoffs from economic reforms. In this scenario, then, elected officials would be unlikely to pursue reforms and, if they did, they would likely be voted out of office.

Another set of expectations has been more optimistic about the ability of democracies to engage in good policymaking. Frye (Reference Frye2010) notes that democracies engage in good economic policymaking as long as political polarisation between the branches of government is low. In a similar vein, Nooruddin (Reference Nooruddin2011) finds that governments ruled by coalitions are more likely to produce stable predictable policies with lower growth rate volatility. More broadly, scholars like Rodrik (Reference Rodrik2000) have characterised democracy as a meta-institution that generally promotes good economic policymaking. All of these explanations are consistent with the expectation that democracies can successfully limit narrow but powerful economic interests (Hellman, Reference Hellman1998; EBRD, 1999). In short, there are empirical reasons to think democratic institutions are good for economic policymaking along with compelling theoretical explanations.

Another important aspect of how democracy may shape economic policymaking is that democratic leaders may have better and more reliable information about what the public wants. This, in turn, may allow leaders to be more flexible in adopting and reversing policies. Competitive elections alone are an important sign of what the public wants and supports. Furthermore, local knowledge may promote better governance when local citizens are included in the design and implementation of policies (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1990; Grindle, Reference Grindle2007). Furthermore, democratic leaders may also be able to more confidently rely on popularity in certain areas to do unpopular things in less salient issues. For instance, Culpepper (Reference Culpepper2011) offers a convincing explanation of ‘quiet politics’ in which politicians can make dramatic and possibly unpopular changes to economic policies of which the public is largely unaware. Gunes (Reference Gunes2021) also demonstrates the important impact of policy attention diversity – how many policies legislators and the public pay attention to – on investors’ behaviour. In short, issues that receive limited public attention may insulate policymakers in highly democratic systems.

In authoritarian countries, however, leaders may have greater uncertainty about the public’s potential reaction and their own ability to stay in power. Authoritarian leaders face both institutional uncertainty about whether they will continue to stay in power and informational uncertainty about what the public wants and what will provoke a major backlash including large-scale public protests (Schedler, Reference Schedler2013). As such, in less democratic countries, policy change may be slower and, in some cases more concerned about a public reaction which is both difficult to predict and potentially high stakes because it could result in a loss of power that cannot be easily regained in regularly held competitive elections.

Additionally, authoritarian countries can be characterised by bureaucratic policymaking. Bureaucratic-authoritarian policymaking was much studied in Latin and South American (O’Donnell, Reference O’Donnell1973; Remmer and Merkx, Reference Remmer and Merkx1982; Schneider, Reference Schneider1991) and later in the Chinese case especially regarding policy experimentation (e.g. Hasmath et al., Reference Hasmath, Teets and Lewis2019). This style of policymaking can result in bureaucratic in-fighting that slows the policy process even when public input is limited or entirely absent. For instance, Remington (Reference Remington2019) has documented how this authoritarian bureaucratic policymaking has been used in Russia and China including in the arena of pension policy. Authoritarian bureaucratic policymaking largely excludes citizens’ feedback and Remington further notes that this policymaking is especially centralised in Russia.

We can see this effect of regime type on pension policy making in Hungary and Russia. The relatively more democratic policymaking in Hungary explains two aspects of its pension reforms: why its government was able to raise the retirement age in the 1990s and, somewhat unexpectedly, why the government was able to quickly reverse pension privatisation in the 2000s. Hungarian leaders in the 1990s were relatively confident about the public consensus in favour of market-oriented reforms which included raising the retirement age. Indeed, even in the late Communist era, the Hungarian government had pursued market reforms atypical for the region include promoting small businesses and introducing an income tax (Kornai, Reference Kornai, Fehér and Arato1991). Furthermore, Hungarian citizens expressed little confidence in the then existing pension system thereby paving the way for acceptance of a structural overhaul (Müller, Reference Müller1999).

When the Hungarian government pursued a reversal of pension privatisation, leaders were also reasonably confident about the other sources of public support which made the policy reversal a matter of limited interest for most people. Furthermore, the consequences of being wrong meant waiting for the next free and fair and competitive election. By contrast, in an authoritarian regime there might be a greater concern that a short-term loss would result in a longer term or even permanent removal of specific leaders or political parties from power.

The less democratic policymaking in Russia in the 1990s and especially in the 2000s helps to explain why the Russian government delayed raising the retirement age until 2018 and why reversing pension privatisation was done more slowly and incrementally in Russia. In Russia, policymaking was characterised by high-level bureaucratic battles and uncertainty about the public’s reactions to policy changes (Wilson Sokhey, Reference Wilson Sokhey2017). For instance, largely unexpected protests about changes to pensioners’ benefits in 2005, which are still the largest post-communist protests over social issues to date, show that the government failed to anticipate popular reactions. Footnote 6 Because leaders in Russia did not rely as much on regular free and fair and competitive elections after 2007 (the first Duma election in which United Russia won an outright majority), the stakes were higher for being wrong about public sentiment and people’s willingness to protest in Russia than in Hungary. In Hungary, leaders and parties would have to wait for the next election. In Russia, there was a greater risk of facing protests and pushback that could threaten the government’s stability.

The comparison of post-communist pension reforms in Russia and Hungary is useful for articulating our theoretical explanation and gauging its plausibility. These cases provide rich descriptive evidence about how and why democracies and authoritarian regimes engage in different economic policymaking.

Case studies of cost-cutting pension reforms: Russia and Hungary

Comparing Russia and Hungary allows us to leverage a most similar case comparison in which many potential causal factors are the same, but there is a crucial difference (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1971). Russia and Hungary both share a Communist legacy, albeit with unique traits, that has resulted in broad commitments to pension provision. In the post-communist period, both experienced recession as well as effects of the 2009 financial crisis which increased fiscal pressures on budgets, including pension systems. Russia and Hungary vary on the key dimension of regime type. Case studies like these are especially useful for making descriptive inferences and helping us better theorise about important causal mechanisms (Gerring, Reference Gerring2004), which we see as the primary contribution of our work here.

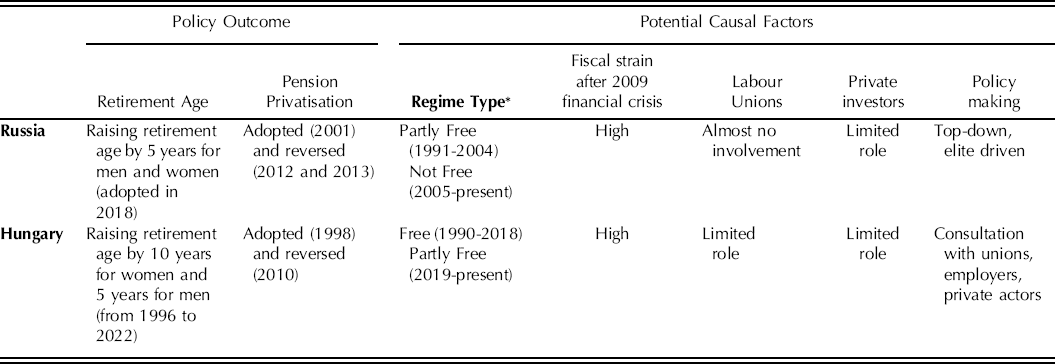

Table 4 summarises our comparison of Russia to Hungary.

Table 4 Comparing Russia and Hungary on cost-cutting pension reforms, 2009-2021

* Regime type is based on the current Freedom House ranking (Freedom House, 2021). Freedom House rankings are calculated on a weighted scale based on a country’s civil liberties and political rights which are numerically coded and then used to group countries into free, partly free, and not free. The Freedom House scores are highly correlated with another standard measure of democracy, the Polity score, which ranges from -10 to 10 with 10 being the most democratic (Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Gurr and Jaggers2019). On Polity, Hungary received a “10” through 2018. Russia received a “3” from 1993-1999, a “6” from 2000-2006, and a “4” from 2007-2018.

As Table 4 reveals, despite similar circumstances in many regards, Hungary raised its retirement age sooner and higher, and nationalised private pensions earlier and more quickly than Russia. We next address these two important areas of reform – raising the retirement age and reversing pension privatisation – in turn.

Raising the retirement age

Raising the retirement age is one of the least popular policies a country can pursue. It is highly visible and it is typically very unpopular even if it is phased in. Hungary raised its retirement age in the mid-1990s with little public backlash. Russia delayed doing so until after Putin’s fourth presidential election in 2018 despite recognition among many economists and policymakers that such an increase was necessary. One of the main reasons for Russia’s delay in reforms was the level of opposition that Yeltsin faced from the Duma in the 1990s. The Hungarian government, by contrast, was more unified in its pursuit of market-oriented reforms.

Hungary

Hungary raised its retirement age during a period that was very politically competitive, but during which there was also a consensus favouring market-oriented reforms. As early as 1990, international organisations and domestic policy advisors were calling for drastic reforms which included calls for overhauling the welfare state by cutting and restructuring benefits (Simonovits, Reference Simonovits, Müller, Ryll and Wagener1999). Footnote 7 Explicitly included in these reforms were calls for pension reform which entailed raising the retirement age. Raising the retirement age seemed to be almost a given with the real debates being about introducing pension privatisation (Gál,Reference Gál, Müller, Ryll and Wagener1999). Indeed, observers of Hungarian pension reform in the 1990s noted that many experts had considered there to be an obvious need to overhaul the pension system even in the 1980s before communism ended (Ferge, Reference Ferge, Müller, Ryll and Wagener1999). The consensus about the need for market-oriented reforms and an overhauled welfare system paved the way for what are often unpopular reforms.

The pension age had been legislated to increase in 1993, then the increase was paused, and taken up again in 1995. In 1995, the MSzP socialist government of the left began making proposals to reform the retirement system including raising the retirement age. It is remarkable both that a left-wing government was the one to propose raising the retirement age, and that there was limited public opposition to the proposal. By fall 1996, the legislative proposal was introduced, discussed, and passed via a roll call vote. Footnote 8 Notably, the MSzP government introduced the bill two years before it was up for re-election suggesting that it wanted distance between a potentially unpopular move and its re-election.

The only organised opposition in Hungary to raising the retirement age came from trade unions, a common source of opposition to such a move. Complaints about the increase led to compromises about phasing in the increase more slowly, especially for women (Ferge, Reference Ferge, Müller, Ryll and Wagener1999). There are no reports of mass protests or other organised opposition. Indeed, the accounts of pension politics in the 1990s largely gloss over the increase in the retirement age and focus on the relatively limited debate about the more controversial move to introduce pension privatisation (Ferge, Reference Ferge, Müller, Ryll and Wagener1999; Gál, Reference Gál, Müller, Ryll and Wagener1999). Simonovits (Reference Simonovits, Müller, Ryll and Wagener1999) even refers to raising the retirement age as ‘inevitable’ before moving on to discuss the intricacies of structural reforms. Even the bureaucratic debates at the time were about how much, not whether, to raise the retirement age. Footnote 9 The Finance Minister, Lajos Bokros, resigned in early 1996 because he did not think the government was going far enough in cutting expenditures and reducing the social fund deficits, not because he thought it was going too far in things like raising the retirement age. Footnote 10

In short, although raising the retirement age was not considered popular, there was a consensus among those in the government that it was necessary and the public backlash was limited, especially compared to political fights over this in West European countries.

Russia

Russia inherited an expensive, but not overly generous, system of old age support from the Soviet era which was particularly hard to maintain given the country’s shrinking and ageing population (Cook, Reference Cook2007). In the deep economic recession of the 1990s, retirees were often not paid the pension benefits that they were owed and attempts at structural reforms failed (Chandler, Reference Chandler2004). Russia faced two major economic crises in the 1990s in addition to on-going battles between the executive and the legislature over economic reforms.

Once the economy recovered after 2000, one of Putin’s early successes was that he managed to pay delinquent pensions and then index pensions to inflation (Chandler, Reference Chandler2004). Putin had a big incentive to address pensioners’ problems because pensioners in Russia have been politically active and influential voters in the Yeltsin and Putin periods (Javeline, Reference Javeline2003). As a result, there was a significant increase in pension payments through 2014, including after the 2009 financial crisis (Sinyavskaya et al., Reference Sinyavskaya, Biryukova, Ermolina and Faizullina2016). At a time when the incomes of most Russians were falling, pensioners were among the few groups that did not see a decline in real income. Pensioners appear to have been especially well-protected with stable incomes even during later economic stagnation in 2012 (Sinyavskaya et al., Reference Sinyavskaya, Biryukova, Ermolina and Faizullina2016), likely because they are an important source of political support for Putin.

In Russia in the 1990s, there was never a political consensus behind market-oriented reforms. Yeltsin never enjoyed majority support in the Duma. Russia consistently received advice to increase its retirement age, but this was never even a serious policy proposal in the 1990s. When Putin came to power in the 2000s, he had no reason to take up this very unpopular measure as he consolidated his power.

The retirement age was only raised in 2018 when the government announced a high profile and very unpopular plan to raise the retirement age from fifty-five to sixty-three for women and from sixty to sixty-five for men. Footnote 11 Russian authorities took steps to mitigate public backlash. First, they strategically chose to announce the measure just after the 2018 presidential election. Many thought this decision explains why trust in Putin fell from 52.4 per cent in November 2017 to only 36.8 per cent by September 2018. Footnote 12 The question of raising the retirement age was also downplayed in major political speeches like Putin’s annual presidential address to the Federal Assembly which barely mentioned this significant policy change Footnote 13 . Finally, some limited concessions were made. For instance, Putin reduced the originally proposed increase in the retirement age for women from sixty-three to sixty.

According to a 2018 Public Opinion Foundation survey, 80 per cent of citizens were opposed to the reform with only six per cent in favour. Citizens’ main reasons for opposing the increase include anxiety about not reaching the retirement age (a valid concern in regions of Russia where average male life expectancy does not exceed the new retirement age), difficulties for older people in getting a job, workers’ declining productivity and worsening health in the years before retirement. Footnote 14 In 2018, protests against raising the retirement age were held in major Russian cities, but had no effect on the government’s decision. Footnote 15

The raising of the retirement age in Russia reveals a policy process dominated by political elites and bureaucrats with limited public input and which is somewhat inconsistent. There are two important implications. First, this process is emblematic of authoritarian social policymaking. The Russian government was concerned about a potential backlash and took measures to mitigate public opposition, yet we do not see any mechanisms through interest groups, political parties, or elections by which the public was involved in the policymaking process. Second, this process does not suggest a short window of opportunity for policy change. Fiscal pressure created an impetus to implement cost-cutting measures. A counter pressure (the medium-term financing gap) led to a reversal of pension privatisation. A longstanding demographic factor (an ageing and shrinking population) created pressure to raise the retirement age. Although there is public opposition to a higher retirement age, the government appears determined to do so.

Reversing pension privatisation

Pension privatisation is a more complicated pension reform about which people are much less aware. Furthermore, in Hungary and Russia, the governments adopted a kind of partial pension privatisation which resulted in citizens being even less aware of how the reform worked or, in some cases, that it was happening at all. In this case, the Hungarian government was less concerned about a public backlash even though it was operating under a competitive democratic system at the time and the Russian government was not. Additionally, the Hungarian bureaucracy was not divided on the issue of pension privatisation. In Russia, there was no reason to think that the Russian public would be particularly upset about a reversal because pension privatisation had not changed the social contract for most citizens (Wilson Sokhey, Reference Wilson Sokhey2017). Furthermore, Russian citizens were poorly informed about pension privatisation and the level of investments in the privatised portion was low. Instead, bureaucratic in-fighting in Russia slowed the reversal. As such, the democratic country reversed more quickly and the authoritarian country made a slow, incremental reversal.

Hungary

In the 2000s, Hungary has been more democratic than Russia especially before 2019. Hungary quickly reversed pension privatisation with limited public discussion. Hungary was a pioneer of market-oriented reforms among post-socialist countries. It was the first European country to implement a privately-managed pension system in 1998 with World Bank guidance. Since the 1980s, the World Bank has promoted the idea of abandoning expensive PAYG schemes in favour of pension privatisation in order to reduce poverty and promote financial sustainability in transitional countries. Pension privatisation is argued to encourage investment, capital market development, and macroeconomic growth (Holzmann et al., Reference Holzmann, Orenstein and Rutkowski2003).

The Hungarian pension system in the 1990s faced several challenges that led policymakers to consider pension privatisation, including a large pension fund deficit and inequitable benefits across groups (Szikra, Reference Szikra2018). Instead of making parametric changes like cutting benefits for certain sectors or changing the benefit formula, Hungary made a structural change and switched to a mixed pension system with privately managed individual accounts (Fultz and Ruck, Reference Fultz and Ruck2001).

As elsewhere, the hope was that pension privatisation would stimulate economic development, improve personal retirement savings and provide more domestic financial stability (Rocha and Vittas, Reference Rocha, Vittas, Feldstein and Siebert2002; Simonovits, Reference Simonovits2011a). The Hungarian Socialist Party (MSzP) did not meet any serious opposition to the adoption of pension privatisation in 1998. There was no major public debate, but the government did incorporate feedback from trade unions, experts and pensioners’ associations (Szeman, Reference Szeman2003). In the new system, 75 per cent of contributions went to the pay-as-you-go pension portion and 25 per cent went to the privatised portion. So, the privatised portion in Russia and Hungary was approximately the same.

The staggered increase in the retirement age contrasts with the relative quickness with which pension privatisation was reversed. The 2009 financial crisis decreased Hungary’s GDP by 9 per cent in just one year, which caused an increase in the budget deficit. The Hungarian leadership under Viktor Orban focused on a populist strategy in which pensions were not a prominent issue (Csehi, Reference Csehi2019). The crisis triggered discussions about raising the retirement age further and the reversal of the already criticised privatised pension system (Simonovits, Reference Simonovits2011b). Ultimately, weak competition between private pension funds, high administrative costs, and substantial contributions diverted from covering PAYG benefits caused the privatised pillar to be closed down. Furthermore, Hungarian citizens had limited interest in pension privatisation’s adoption and reversal. According to polls, about 45 per cent of Hungarian citizens knew little about the pension policy reform (Guardiancich, Reference Guardiancich2008). According to a 1998 survey, more than half of Hungarians felt ready to switch to a funded pension (Palacios and Rocha, Reference Palacios and Rocha1998).

Because Hungary had adopted a moderate, partial pension privatisation (6-8 per cent of contributions went to the privatised portion), there were no domestic stakeholders invested in keeping the system alive (Wilson Sokhey, Reference Wilson Sokhey2017). The result was a swift reversal in December 2010 with virtually no public discussion (Casey, Reference Casey2012; Gál, Reference Gál2012). Unlike Russia, there was no bureaucratic in-fighting to slow the reversal of pension privatisation. Furthermore, because of the quick reversal, private pension funds did not have time to lobby citizens or the government to stick with the privatised portion (ILO, 2018). Hungarians were given only a few short weeks to choose whether to switch back; those who did not forfeited their rights to any portion of the privatised benefits. What was at first only a temporary suspension of contributions to the privatised portion became a permanent moratorium in 2011. Footnote 16

Alternations in power between the left-wing MSzP and the right-wing Fidesz party led to adjustments in the pension system in other areas like pension privatisation, but did not result in any backtracking on raising the retirement age. During this time, there was a temporary freeze of contributions to the privatised portion of pensions and a subsequent increase to the contribution rate (from 6 per cent in 1998 to 8 per cent in 2003). These changes caused by political cycles affected the stability of the entire system (Simonovits, Reference Simonovits2011a). At the same time, it is notable that there were no serious debates about halting or reversing the increase in the retirement age. The Hungarian government has never backtracked on raising the retirement age, a measure adopted during a very politically competitive time.

Russia

Russia was slow to reverse pension privatisation primarily because of internal bureaucratic struggles. The 2005 protests over changes to benefits and the importance of pensioners were likely central in Putin’s mind and in the minds of other leaders even though pension privatisation does not directly affect current retirees. Reports of the 2005 protests include pensioners shouting ‘Down with Putin!’ amid the largest protests against the government since the fall of communism. Footnote 17 These protests constituted the first major challenge to Putin since he had assumed office in 2000. Putin was likely concerned about an unexpected public reaction to pension privatisation reversal because of these previous protests.

Furthermore, as part of a larger package of economic and institutional reforms, aimed, among other things, at the development of the financial market in Russia, Putin himself had backed the passage of legislation partially privatising pension provision in December 2001. The reform meant that a portion of workers’ mandatory pension contributions made would be diverted from the pay-as-you-go system that had been in place since the Gorbachev period and allocated to individual accounts which would, in principle, be privately invested. In the new pension system in Russia, 16 per cent of the total 22 per cent of contributions went to the pay-as-you-go pension portion and the other 6 per cent went to the privatised component.

The reform was slow to take off, public knowledge about it was limited and the public’s trust in private financial institutions was low. Although privatisation was designed to shift some of the cost of pension provision away from the government onto citizens while boosting domestic savings and investment in Russia’s economy, in the short term there was a financing gap because fewer current contributions could be used to cover current benefits. State subsidies to the Pension Fund increased, causing more concern among bureaucrats in the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Economic Development (Wilson Sokhey, Reference Wilson Sokhey2017).

Debates over reversing pension privatisation took place between the social block of the government, which supported the reversal, and the economic block (along with private pension funds), which supported privatisation. These bureaucratic debates reflect, in part, the institutional complexity and layering of pension reforms. Footnote 18 This style of bureaucratic policymaking is an important aspect of Russia’s authoritarian policymaking. Other scholars have confirmed that the reversal of pension privatisation was also characterised by very little input from the public (Aasland et al., Reference Aasland, Cook and Prisyazhnyuk2017 and Cook et al., Reference Cook, Aasland and Prisyazhnyuk2017).

Alongside the bureaucratic struggle, the economic pressure for pension policy reversal was also significant. In the period from 2005 to 2014 the average annual inflation was 9.2 per cent and the profitability of investing pension savings for the same period of time varied from 5.8 per cent in private management companies to 3.9 per cent in non-state pension funds. The key reasons for low profitability of investments were macroeconomic instability in Russia, a small stock market, and limited financial instruments for the investment (Kozlov, Reference Kozlov, Voronin and Yemelyantsev2017). Because the reform was only partial, levels of investment were low, private investors were making limited profits, the investment performance of pension funds was low, and citizens were not seeing significant benefits. Besides, most private pension funds had been kept in state banks rather than invested in the private sector, so even financial firms that supported the initiation of private accounts had lost interest.

In 2012 and 2013, the government backtracked on pension privatisation in order to reduce the pension fund deficit and maintain pensioners’ standard of living. The reversal was caused by a combination of the policy’s short to medium term costs and the lack of entrenched domestic interest in support of privatisation (Wilson Sokhey, Reference Wilson Sokhey2017). The fiscal challenge created by the on-going financing gap was exacerbated by the 2009 recession and Ukrainian crisis in 2013. Contributions to the privatised portion of the Russian pension system were finally permanently eliminated in 2014. Those who previously contributed are allowed to keep their funds in the privatised accumulative portion (the nakopitelnaya chast’), but are not allowed to make further contributions to it and new workers cannot opt into this system. Footnote 19

Conclusion

Our comparisons reveal that regime type shapes the policymaking process and policy outcomes. Some scholars posited that authoritarian regimes would be able to pursue market-oriented reforms more easily and more quickly. Others have argued that democracies will be better able to enact policy changes. We find evidence that democratic government can be more flexible and enact policy changes more quickly than authoritarian regimes.

The democratic Hungarian government could adopt an unpopular but necessary reform sooner and could reverse course on pension privatisation more quickly than the authoritarian regime in Russia. Hungary had begun the very unpopular – but arguably very necessary – step of raising the retirement age in the 1990s and sustained this measure. In the 2000s, the democratically elected Fidesz super majority pushed through a reversal of pension privatisation in less than a month and with no legislative debate when its leaders deemed this to be a necessary response to the 2009 global financial crisis. The Hungarian reversal of pension privatisation was strongly criticised by some observers (e.g. Simonovits, Reference Simonovits2011b), but was transparent and did not keep private pension funds in limbo as in Russia.

By contrast, Russia, the much less democratic country, put off the very basic step of increasing the retirement age until 2018 more than twenty years later than the Hungarian government. Furthermore, the Russian government reversed pension privatisation slowly and incrementally and with little transparency about the future of the system. Indeed, Russia’s pension privatisation system still exists in name and has suffered a de facto death. In the Russian case, the institutional and information uncertainty that is more prevalent in authoritarian regimes made the government more cautious about the public’s potential reaction than in Hungary.

In other words, a democratic country took an unpopular but necessary measure and kept it in place directly in contrast to the expectations of those writing in the early 1990s who expressed concern that countries could not democratise and adopt market-oriented reforms at the same time. There is often an assumption that unpopular measures like raising the retirement age or reversing a major policy reform would be harder in a democratic country because democratic policymaking might slow things down as different viewpoints are expressed and political debates slow the legislative process. The comparison of Hungary and Russia shows that this is not always the case. Leaders in authoritarian countries like Russia may face greater institutional uncertainty about staying in power and information uncertainty about what the public wants and how the public is likely to react.

In keeping with the theme of this themed section, we show the importance of comparing Russia to other European cases. Often, research focuses on EU countries in part because the EU finances reports and studies on its own member countries. Russia has long been subject to those who focus on its unique and distinctive traits – which all countries have – without considering why Russia diverges. Our case studies show that Russia faces many of the same economic and social pressures as other developed European countries yet handles them differently because of its authoritarian regime. Somewhat optimistically and contrary to many existing explanations, the Hungarian case further shows that democratic policymaking can successfully undertake difficult reforms and even reverse course quickly. In both cases, regime type influenced the information and certainty leaders had such that democracy and authoritarianism played crucial roles in shaping reforms.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Linda Cook and Professor Michael Titterton for organising this themed section and for their invaluable comments and suggestions on the article. Daria Prisiazhniuk acknowledges that the article was prepared within the framework of the Basic Research Program at HSE University.Footnote ‡