The ongoing revolution in Belarus is a musical one.Footnote 1 Indeed, the iconic Russian music critic Artemii Troitskii believes the “phenomenal hyperproductivity” of the contemporary protest song scene in Belarus is “like nothing else in world music history.”Footnote 2 In addition to a huge wave of recorded material, the streets have been humming with protest songs, from traditional Belarusian folk songs such as Kupalinka to the 1980s rock anthem Khochu peremen (“I Want Changes”) by Viktor Tsoi's Kino.Footnote 3 Songs can electrify a crowd through a shared performative unisonance, allow individuals to overcome their anxieties, and also provide verbal reference points that consolidate meaning and provide a sense of shared purpose. Or as poet Yuliya Tsimafeeva put it: “A poem read aloud and a song sung in the public space become the weapons of the revolution.”Footnote 4

This is clearly what popular video blogger Siarhei Tsikhanouski realized when, in May 2020, he called upon his YouTube subscribers to learn the words to the song Mury (“Walls”), in Belarusian, Russian, or both; “learn it, it will be playing at the squares,” he appealed in a video uploaded on May 27.Footnote 5 Mury is a Belarusian version of Polish bard Jacek Kaczmarski's 1978 song Mury, which in turn was translated and adapted from the Catalan original entitled L'estaca (“The Stake”), written in 1968 by Luis Llach.Footnote 6 Just as Kaczmarski's song became an anthem of the Polish Solidarity movement, the Belarusian Mury, with lyrics by prolific poet Andrei Khadanovich, has been part of the protest music repertoire since Khadanovich first performed it after the 2010 presidential elections.

[Chorus]

Разбуры турмы муры! Tear down these prison walls!

Прагнеш свабоды—то бяры! You want your freedom, take it all!

Мур хутка рухне, рухне, рухне— The wall will soon crumble, crumble, crumble,

І пахавае свет стары! And we'll see the old world fall!Footnote 7

After Tsikhanouski was refused registration as a presidential candidate and later imprisoned, the song gained enormous popularity, being played at the campaign rallies of his wife Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaia, who ran in his place, as well as at mass protests in the aftermath of the rigged election on August 9.

This example, alongside Kino's Khochu Peremen, shows that trajectories of influence are of course transnational: protest cultures are inherently border-crossing phenomena, with borrowing, adaptation and translation playing crucial roles.Footnote 8 The Belarusian events have drawn inspiration from—as well as influenced—both eastern (especially Russia, but also Armenia's 2018 revolution and Kyrgyzstan's protests of 2020) and western neighbors (especially the central and eastern European events of 1989 [see Bekus in this cluster] but also reverberating in the Polish abortion protests of fall 2020). At the same time, local agency and rootedness in national tradition are vital to widespread mobilization through shared affect.

A specific feature of Belarusian society is that poets often provide the lyrics to songs that become entrenched in the public consciousness: in other words, the “high” culture of poetry easily translates into the “mass” culture of popular music.Footnote 9 This symbiotic relationship between written and sung verse gives the poetic word a rare power. What is specific to the 2020 unrest in Belarus is that fast digital distribution has added a potent ingredient to the mixture. YouTube, Telegram, Facebook, and other social media platforms have played a critical role in spreading information and mobilizing public gatherings, but they have also acted as a vital conduit for creative expression.Footnote 10 Poetry, music and music videos, visual art and short films have been posted and spread online, providing a creative effervescence to undergird the prolonged protests.Footnote 11

While protest verse has long been part of the repertoire of contention in Lukashenka-era Belarus, it never previously occupied such a prominent role in mobilizing social movements. In 2010, for instance, the poet Uladzimir Niakliaeu ran as a presidential candidate—and was beaten and arrested on “election” night on his way to a protest—but his verses played a relatively minor role in his campaign.Footnote 12 Ten years later, however, in a much more consolidated social media environment, poetry and music are a crucial instrument for cementing a sense of collective identity among protestors, establishing transnational solidarity, and affecting the emotional regime of Belarusian society.Footnote 13 An important element of this poetic activity is its bilingualism: whereas Belarusian literature has traditionally and until recently placed a premium on the Belarusian language, a new conviviality is emerging, whereby Russian and Belarusian are gaining an equal footing as languages of creative protest. The Belarusian revolution is a movement of civic nationalism, a fact also reflected in its songs.

Old Poems with New(?) Meanings

Modern Belarusian-language literature began, after a long hiatus in which Polish and Russian were the culturally dominant codes, with verses of national “awakening” by poets such as Frantsishak Bahushevich (1840–1900), Ianka Kupala (1882–1942), and Iakub Kolas (1882–1956).Footnote 14 Poetic works from the early twentieth century have found an uncanny resonance a century on, due to the parallels in the political situations: despite now being a sovereign country, a post-dependency narrative of an absence of clear national identity has remained strong.Footnote 15 Alongside the resurgence of the pre-Soviet red-white-red flag, therefore, verses proclaiming a national collective have featured regularly in protest-related online content, such as Kupala's Khto tam idze? (“Who Goes There?,” 1905–1907), which also offers an apt description of mass street demonstrations:

А хто там ідзе, а хто там ідзе Say, who goes there? Say, who goes there?

У агромністай такой грамадзе? In such a mighty crowd, oh declare?

—Беларусы. - Belarusians.

… …

А чаго ж, чаго захацелась ім, And what is it, then, for which so long they pined,

Пагарджаным век, ім, сьляпым, глухім? Scorned throughout the years, they, the deaf, the blind?

—Людзьмі звацца.Footnote 16 - To call themselves human.Footnote 17

One video, released by students and faculty of Belarusian State University as a statement of solidarity with victims of police violence, features a series of talking heads wearing white balaclavas, each reciting a segment of this poem. The final line is delivered in unison by all of the readers, and the picture cuts to an image of the participants simultaneously removing their face coverings, thereby performing their transition from oppressed mass to visibility, subjectivity, and “humanness.”Footnote 18 The act of demasking also sets up a contrast with the riot police (OMON), known for roaming the streets of Belarusian cities in black balaclavas. This reading of Kupala's verse thus reinforces the narrative of the present-day protests being a moment of national awakening.

Another early poem shared widely through social media was Iakub Kolas's Voraham (“To Our Enemies,” 1916), whose address to imperial Russia clearly resonated with Vladimir Putin's overt support of the Lukashenka regime in the aftermath of the falsified elections.

…I вы цяпер рукамі кáта …And even you are now prepared,

Гатовы згоду дараваць? With your hangman hands,

To concede our acquiescence?

Але ці можна ў вас брата, But tell us, brothers, should

Скажэце, каіны, прызнаць? We see in you Cain's essence?

Вам не па сіле груз цяжэрны The burden of war is too heavy for you,

Вайны, што самі вы ўзнялі, a weight you lifted yourselves,

Знішчэнне, мах яе бязмерны, Immeasurable destruction,

Згінота цяжкая зямлі! The earth's heavy demise.

Не вы дасце народам свята, You are not the ones to free nations,

Не вам пажар вайны заліць! To quench the fire of war,

Дык рукі прэч, забойцы, каты! So hands off, killers and torturers!

Не вам аб згодзе гаварыць!Footnote 19 We'll have your words no more.

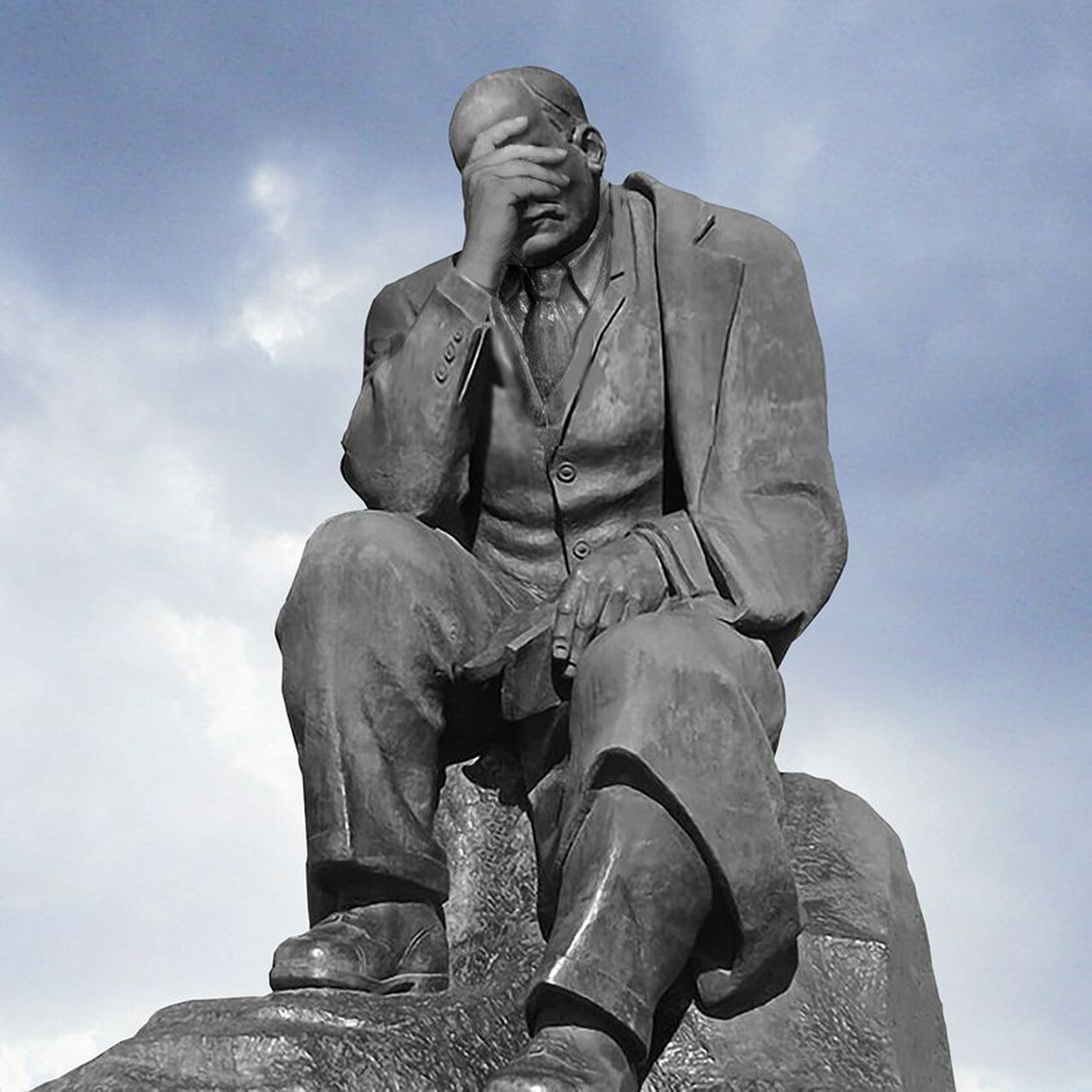

The continuity of the myth of Slavic brotherhood throughout Soviet times and beyond allows this verse to retain its ironic bite, while the trope of national liberation remains relevant in 2020—both in the domestic context of the attempt to overhaul the dictatorship and in the international realm, where Russian state hegemony over Belarus is clearly felt in Putin's financial and administrative backing of Lukashenka. Kolas also features in a visual meme by the prolific artist Uladzimir Tsesler, who has contributed a multitude of shareable images on various themes related to the protests and police violence. On September 7, he posted a manipulated photograph of the statue of Kolas that stands on a central square in Minsk, in which the poet's stone effigy holds his head in despair. An ironic commentary using Soviet-era monumental art,Footnote 20 the image appears to speak both for the poet as national hero and the late-Soviet statue, both of which, he suggests, condemn the intransigence of the authorities (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Image of Iakub Kolas monument, posted by Uladzimir Tsesler on September 7, 2020. https://www.facebook.com/vtsesler/posts/2698113283809416.

#Kультпратэст #Kультпротест #Cultprotest

Although the protests took off in earnest on the night of August 9, cultural resistance to the new round of falsifications had been building up well before. On July 1, more than twenty musicians, writers, actors, and other cultural figures released a video in which they expressed their anger and resentment at twenty-six years of dictatorship, and demanded free elections as well as the release of all political prisoners in Belarus.Footnote 21 The video was distributed through YouTube, Facebook, Telegram, and other social media and accompanied by the hashtags #культпратэст #культпротест, and #cultprotest. Meanwhile, many other cultural figures posted the same 400-word long text on social media, in which they announced that “we, workers of the cultural sphere, declare a #cultprotest,” also using the same Belarusian, Russian, and Romanized versions of the hashtag. The statement continued:

Under the #cultprotest hashtag, we will do what we do best—create art. And it will be judged …by the newly awakened people of Belarus. Our #сultprotest will sing, shoot videos, draw pictures and hold events for free citizens, not for the authorities we have all had enough of.Footnote 22

Thus, a digital rallying cry was born, which has continued to flourish and adapt as the street protests go on. The website cultprotest.me is a constantly growing repository of protest images that can be shared without restriction, and the hashtag accompanies a wide range of creative material, from songs and music videos to poetry and status updates in prose.

The original #cultprotest video is bilingual, with a clear majority of addresses in Russian. Likewise, the proliferation of creative content under these hashtags and others, or none at all, has reflected the growing ease with which the two official languages of Belarus coexist as languages of cultural expression. The rich variety of protest poetry that has sprung on the personal Facebook pages of poets before being syndicated in online resources and compilations—including as translations into Russian, Polish, Ukrainian, English, and German—has featured verses originally written in both languages, as well as, on occasion, English.Footnote 23 A Russian-language poet such as Dmitrii Strotsev was previously better known and appreciated in Moscow than Minsk, but has emerged as one of the most prominent voices through the energetic immediacy of his verses. For instance, in his Kak udivitel΄no (“How Amazing”), written and posted after the mass opposition rally on August 23, he skillfully combines the mundane details of city life with the sensory overload and emotional charge of participating in the event:

…взявшись за руки пройти по проспекту walking down the boulevard hand in hand

как в последний раз like last time

и вдруг на площади задышать and suddenly on the square breathing

свободно freely

ключи у соседей the neighbors have the keys

у собаки вода и запас сухарей на сутки the dog has water and enough biscuits for a whole day

пройти через двор going through the courtyard

где беспечная падает тень where a reckless shadow falls

выйти на улицу coming out on the street

где святая бредёт повседневность where holy humdrum trudges

может эти двое из всех maybe out of everyone these two

движутся в наше безумие are moving into our madness

на расстрел to be shot

соскочить jump off

ещё ничего не поздно it's not too late

тошнота паническая атака nausea panic attack

конечно ты можешь всегда повернуть of course you can always turn

назад back

глаза и глаза и глаза eyes and eyes and eyes

шеф усё пропало мы победим all is lost boss we are going to win

шеф усё пропало мы победим […]Footnote 24 all is lost boss we are going to win […]Footnote 25

Strotsev's strong and highly accessible voice of protest was almost certainly a factor in his arrest on October 21: having disappeared from the streets for several hours, he was registered at Akrestsina prison in Minsk and sentenced to 13 days’ imprisonment the following day.

Transnational solidarity is a crucial element of modern social movements. Strotsev's arrest led to calls from several international scholarly associations for his release, and poets have been important figureheads presenting the Belarusian events to an international audience.Footnote 26 Hanna Komar, who was likewise arrested and spent nine days behind bars in September, translates her own Belarusian-language verses into English, and has contributed them to resources such as the Vienna Institute for Human Sciences’ invaluable “Chronicle from Belarus”:Footnote 27

вы скралі мой голас you stole my vote

аддайце мой голас! give me my voice back

я буду прыходзіць штодня, i will come every day

пакуль не пачую яго зноў until I can hear it again

ад рэха маіх крокаў let the echo of my footsteps

раструшчацца вашыя crack your

бетонныя сцены concrete walls

ад папроку ў маіх вачах let the reproach in my eyes

разаб’юцца шыбы break the glass

вашых пустых вокнаў of your empty windowsFootnote 28

Alongside Komar's lyricism, poets such as Valzhyna Mort, based in the USA, and Yuliya Tsimafeeva have also been active in giving poetic expression to the protest in English.Footnote 29 Tsimafeeva's first poem composed in English, “My European Poem,” appeals directly to international readers by laying bare the peripherality of Belarusian culture and the pain of expressing herself in her own language:

…Sorry, it's a long poem,

Because it's a long story,

I spent more than two thirds of my life

Under the power of the man

I've never voted for,

Who harassed and suppressed and killed

(They say).

And when I come to the literary festivals abroad,

And when I speak English

I try to tell the complicated history of my country

(When I am asked)

As if I am another person,

As if I am like all those European poets and writers,

Who do not have to get used to the thought

That they could be arrested and beaten

For the sake of their country's freedom.

As if I my ugly history is just a harsh story

That I can easily put out from the Anthology of

Modern European short stories because

It's too long,

And too dull.

When I tell it in English,

I want to pretend that I am you,

That I don't have that painful experience

Of constant protesting and constant failing,

That nasty feeling of frustration and dismay.

I want to pretend that I have a hope,

Because when I tell it in Belarusian

I realize, we all realize, there is none

We can look forward to.…Footnote 30

Shared more than 250 times on Facebook, where Tsimafeeva originally published the poem shortly before the “election,” the sincere expression of anguish and yearning also, needless to say, spoke to many Belarusians.

Poetry and music also play a vital role in supplying emotional templates that mediate responses to events: for example, bearing witness to the gross human rights violations committed by Belarusian law enforcement in prisons and detention centers and channeling social outrage. Conceptual artist Hanna Zubkova has authored one of the most striking poetic descriptions of injury in her lengthy “V tom chisle,” a Russian-language catalog verse of various corporeal wounds inflicted by the OMON and prison guards:

…проникающее ранение …penetrating wounds

живота to the abdomen

с эвентрацией with eventration

тонкого кишечника of the small intestine

слепые ранения– blunt wounds—

десятки случаев dozens of cases

открытая травма external injuries

грудной клетки, to the chest

проникающее ранение penetrating wounds

грудной клетки; to the chest

проникающая травма penetrating trauma

грудной клетки to the chest

с повреждением правого среднего долевогоwith damage to the right middle lobar

бронха bronchus

и развитием гемопневмоторакса […]Footnote 31 and the development of hemopneumothorax…Footnote 32

The poem ends with a reference to the first death that resulted directly from police action: Aliaksandr Taraikouski was shot on August 11, 2020. Through its indexing without commentary of these acts of violence, V tom chisle solicits emotional responses that strengthen the protest movement.

Nasta Kudasava, meanwhile, provides an overtly subjective and empathetic reflection on the anxiety and fear of citizens who have lost friends and family:

Тут кожны баіцца прызнацца, што страціў кагосьці,

што больш немагчыма без жаху ступаць па зямлі:

сасновыя шышкі трашчаць пад нагамі, як косці,

як берцы забойцаў, чарнеюць у травах камлі.

А ў небе—нябесныя сотні, нябесныя шэсці…

А з неба скрозь слёзы, абняўшы нябесны штурвал,

глядзіць ашалелы ад роспачы лётчык Акрэсцін:

“Усё

пазабыта.

Нікога

не

ўратаваў.”Footnote 33

Here everyone is afraid to admit that they've lost loved ones,

That they can't tread the ground without dread,

pine cones crunch under your feet like bones,

the tree roots darken like the murderers’ boots.

In the sky—heavenly hundreds, heavenly marches…

From the sky, through tears, embracing his heavenly helm,

The pilot AkrestsinFootnote 34 looks down, mad, unconsoled:

“It's all

forgotten.

I couldn't

save

a soul.”

Daily crowds of relatives and friends gathered outside Akrestsina and other prisons, waiting to hear about the fate of their loved ones or attempting to deliver personal packages to prisoners, are an essential component of Belarusian life after August 2020, demonstrating the support networks and social solidarity that galvanize civil society. By providing poetic expression to the emotional ordeal of these citizens, Kudasava also weaponizes grief.

The diversity and ingenuity of creative energy that lies under the surface of the Belarusian revolution is impossible to do justice to in a short text of this format. Musicians have recorded dozens of protest songs in myriad genres, from rap to rock to choral music, with accompanying music videos.Footnote 35 Public performances of song have gone viral, such as a video of the guitarist of 90s cult rock group N.R.M., Pit Paulau, baiting a cordon of riot police with a rendition of the group's iconic protest song Try charapakhy (“Three Tortoises”), joined by a raucous crowd of demonstrators;Footnote 36 or a video of a crowd in a central metro station seemingly spontaneously breaking out into a rendition of Kupalinka and other patriotic songs.Footnote 37 Verses old and new have gained a huge significance in generating affect and consolidating collective sentiment. Poets have expressed themselves in Russian, Belarusian, and other languages, using secular and religious imagery,Footnote 38 and the language of children as well as adults.Footnote 39 These verses of defiance, solidarity and empathy, distributed above all by digital means, are an essential component of the revolution—a fact that the authorities themselves tacitly admit when they actively seek out and detain poets and artists. The poets, however, continue to write when they are released; their cultural protest is only strengthened by their penitentiary hardship, and the insurrectionary power of verse grows stronger.