The protests of 2020 in Belarus have often been described as a new 1989, and the photograph of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya against the background of a fragment of the Berlin Wall painted in the colors of the Belarusian flag would seem to confirm it.Footnote 1 Many eastern Europeans felt a moral responsibility to support the Belarusian people in their revolt against autocracy. On August 2, 2020, a group of Polish Solidarity activists published a letter “To our Belarusian friends” in which they sought to portray Belarus as a part of the east European space united by a shared legacy of tyranny and common aspirations for democracy and freedom.Footnote 2 Another spectacular symbolic extension of 1989 to Belarus took the form of a Baltic Way 2020, when on August 23 thousands of Lithuanians created a human chain from Vilnius to the Belarusian border. The initiative was called to demonstrate solidarity with Belarusian protesters and to celebrate the anniversary of Baltic Way 1989, when two million Lithuanians, Latvians, and Estonians had joined hands in a human chain to demand freedom from the Soviet Union.Footnote 3

Thinking of the Belarusian protests as a “new 1989” implies a particular reading of these events as a moment of “synchronization” of the country's development with the post-1989 transformation. It suggests that the processes and ideas that were at the core of “post-communism in the making” in eastern Europe will reverberate in Belarus with the fall of the Lukashenka regime. There is no doubt that the emancipatory appeal of the Belarusian protest is similar to the one that sustained the 1989 revolutions. But will building democracy—the major aspiration of the Belarusian demonstrators—follow the scripts of liberalization and westernization in evidence in other central and east European countries?Footnote 4 Will self-determination in post-Lukashenka Belarus follow the pattern evident in other east European states, with their focus on ethnocentric national identities and the memory of victims of communism?Footnote 5 These questions will remain unanswered until regime change actually takes place, when the new elites that will come to power after Lukashenka start to make their strategic choices. Existing records of protest mobilization and marches, however, provide important insights into the structural changes that have occurred during the protest in the system of historical and cultural references that have shaped the foundation of Belarusian collective memory and identity discourses since 1994.

Ever since Belarus gained its independence, the discursive terrain of Belarusian identity politics has featured the parallel coexistence of two different projects. The official ideology centered on the affirmation of the achievements of the Soviet epoch. The experience of building a socialist state, defending the country against Nazi Germany, and starting a new life in the postwar decades have been incorporated into the story of how Belarusians became a nation.Footnote 6 The history of the Great Patriotic War has been retold in terms of Belarusian national heroism.Footnote 7 The oppositional discourses of Belarusian identity endorsed by multiple political and cultural actors since the late 1980s had promoted a vision of Belarusian identity that combined conservative ethnonationalism and anticommunism with democratic aspirations. Echoing the dominant trope of east European postcommunism, this discourse presented the Soviet history of Belarusians as a story of national suffering. One of the distinctive features of the 2020 election campaign, however, became the absence of these “old” oppositional players and their political agendas. The Belarusian protest mobilization that rapidly formed over the summer did not have its origins in the pre-2020 oppositional ideology. The protests emerged instead in the guise of a new, multi-dimensional space where the ideas previously involved in the symbolic struggles among the official and oppositional elites in the various movements and institutions have now been reappropriated and vested with new meanings by numerous distinct and intersecting groups joining the protests. As this article demonstrates, these “eventful protests” have had important transformative effects by producing abrupt and momentous changes in the socio-cultural imaginary of Belarusian identity.Footnote 8

Global and Local Repertoires of Contention

Protest marches, when analyzed as a form of collective action, have always been characterized by a complex dynamics. The ultimate aim of protests is not only to influence the decision-makers, but also to influence public opinion—supporters, opponents, and bystanders—by communicating to the wider society a message about the protesters’ identity, their values, and the ideas for which they stand. Protest marches—as opposed to rallies and demonstrations assembled in one place—offer a number of important advantages, which have proved crucial in Belarus, where the wide-scale mobilization has not been organized by any political party or social movement. During the marches, the protesters could show themselves to a much larger number of people and attract more sympathizers along the way; marches allow people walking together to get to know each other, to grow together as a protest community, and to demonstrate the resolution of participants.Footnote 9

During the Belarusian protests, the marches also became an important venue where the protesters could respond to the false allegations deployed by Lukashenka in order to justify his refusal to enter into a dialog. As a result, the expressive symbolism of the marches came to play a crucial role in reasserting the attributes of worthiness, unity, number, and commitment.Footnote 10 Furthermore, the Belarusian protests provide an example of a creative adaptation of a variety of globalized patterns and forms of action by employing local, familiar idioms, symbols, and images. Singing “Mighty God” and “Pahonia” on the platforms of Minsk metro stations and in shopping centers emerges as a Belarusian echo of the singing of “Glory to Hong Kong” at Hong Kong shopping malls and airport terminals. The widespread use of umbrellas in white-and-red colors may well carry an implicit reference to the umbrella movement, whereby an everyday object came to be imbued with a new, symbolic meaning, being an implement that unarmed protesters can use to protect themselves from pepper spray attacks.Footnote 11 In Belarus, alongside the political symbolism, the umbrellas also serve to shield demonstrators from the dye used in water cannon that allow the riot police to identify protesters and to arrest them after the protest ends.

The concept “repertoire of contention” underlines the limited set of means and forms of action that a group can employ, with others being precluded for ideological, moral, or tactical reasons. It reflects not only what people do when they make a claim; it is what they know how to do and what society has come to expect them to choose to do from within a culturally-sanctioned set of options.Footnote 12 The emphatically peaceful character of the Belarusian protests, for example, can be read as a strategic choice that has ensured effective mobilization across different social groups. The critique of “Belarusian Ghandhism” as an allegedly ineffectual instrument in the struggle for power overlooks the importance of the societal endorsement of the means of protest.Footnote 13 The resort to violence by the authorities in the immediate aftermath of the election stripped Lukashenka of the appearance of legitimacy and became one of the strongest mobilizing incentives. One of the recurring slogans appearing at the protests, namely “We Belarusians are peaceful people,” reveals a strong reluctance in Belarus to accept the violence, thereby largely determining the repertoire of the means of protest employed.Footnote 14

Protest Imaginaries

The symbolic dimension of the repertoire of contention—protest imaginaries—reveals how the specific means of communication, the cultural forms, and the historical associations become involved in the articulation of the demand for change, in shaping the image of the protesters, and, ultimately, representing their identity. Most analysts agree that the mobilization of protest is facilitated by a group's ability to develop and maintain a set of beliefs and loyalties that contradict those of the dominant groups.Footnote 15 In Belarus, however, the cultural grammar of protest that drives and sustains the protest has been formed during the protest itself through the creative adaptation and reappropriation of ideas, values and frames of understanding deriving from both the official and oppositional ideologies.

An important dimension of protest marches is their capacity not only to demand change but also to perform it.Footnote 16 From this perspective, the street rallies infused with theatrics, music, artistic actions, and engaging with the cityscape not only reflect the choice of symbols, cultural references, and places that have been used to articulate the message, but also create a space in which these “building blocks” of protest activities have been rearranged to bring into existence a new realm of national being. The protests deploy performative strategies to connect various historical events with the reality of protests, thus linking the specific discourse and themes of any given protest with a series of shared cultural and historical values.

One of the most memorable and representative images of the Belarusian protests of 2020 became the photograph of the mass street rally on August 16, which shows the protesters occupying large tracts of space surrounding the Museum of the History of the Great Patriotic War with a white-red-white flag draped around the sculpture “Motherland.” This image does more than simply capture the remarkable scale of protest in Minsk; it encapsulates the essence of the transformation of cultural symbols and their historical connotations, occurring in the course of these same protests. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. The white-red-white flag draped around the ‘Motherland’ sculpture with the Museum of the History of the Great Patriotic War in the background. Photo: Nadezhda Buzhan, Source: Nasha Niva, August 16, 2020.

The new venue of the Museum of the History of the Great Patriotic War (opened in 2014) manifested the prominent role of this historical event for Belarusian identity and statehood.Footnote 17 The design of the museum emphasizes the importance of World War II in the memorial landscape of independent Belarus. Located on the central Avenue of the Victors, the museum forms a monumental composition with the Hero City of Minsk obelisk and the sculpture “Motherland.” The public life of the white-red-white tricolor, on the other hand, has been closely intertwined with the political program for the emancipation of the Belarusian people from the spell of a positive perception of the Soviet past endorsed by multiple oppositional actors.Footnote 18 In contrast to the official ideology, they sought to define the Belarusian nation's independent status through a postcolonial othering of the Soviet past. The focal point of this narrative became the remembrance of the victims of Stalinism and the demand that the wrongs of the Soviet system be redressed.

Becoming a major symbol of the Belarusian protests in 2020, the white-red-white flag, however, did not signify the ideological victory of the old opposition. Instead, it has been reinvented as an emblem of struggle for Belarus without Lukashenka, offering an open frame for the socio-political and cultural choices that might be made in the future. Wrapping the “Motherland” sculpture in the white-red-white flag on August 16 performed an act of illustrative assemblage charged with political symbolism: two previously conflicting frames—the symbol of anti-Soviet nationalism and the epitome of “the glorious Soviet past”—have been combined in a representation of the new Belarus emerging during the protest. In this powerful act of resignification, the heroic pathos of place—reinforced by the iconic, 45-meter-high Hero City of Minsk obelisk—transferred the sense of Belarusian historical heroism to the protesters, who now stand for victory over the authoritarian regime. The regime's defenders quickly understood the powerful appeal of this symbolic message: in the following weeks of protest the area was ringed by riot police. The Obelisk, however, remained a destination point for marching columns until October 11, when for the first time the police forced protesters to change their route.

Shifts in the urban dynamics of the marchers further reflected the power of the historical imaginary: the protest march held on October 18 was redirected to Partisan Avenue and was named the “Partisan March.” In Belarus, the mythologized self-image of the “Partisan Republic” that had played a key role in the victory became the defining feature of the post-war polity.Footnote 19 This image evokes the idea of a people capable of survival under occupation by an alien power and waging an effective and victorious struggle against it. The Nexta Telegram channel makes clear reference to Belarusian history in its announcement: “Partisans come to the march… to demonstrate that we, the descendants of glorious warriors and partisans, are worthy of our ancestors, who once defeated fascism.”Footnote 20 Commenting on the march at Partisan Avenue, a protester interviewed on Belsat TV discussed the benefits of changing location using categories drawn from partisan warfare: “the police had got to know the areas surrounding Stela too well….Changing place means that it will be easier to escape.” Another protester commented on the success of the march: “We walk like partisans, like victors.”Footnote 21

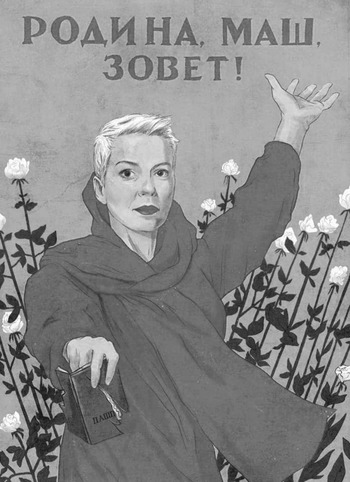

Imagery from the Second World War became an important resource bank for raising the spirits of Belarusian protesters, appealing both to the victorious narrative and to the sense of righteousness encrypted in the Belarusian memory of the war. The important role played by women in the Belarusian protest events was reflected in an art project by Vika Zhukovskaya entitled The Motherland. It represents a woman dressed in white-red colors calling to mind a figure in the famous monument “the Motherland calls” (erected in 1967 in Volgograd), dedicated to the heroes of Stalingrad.Footnote 22 (See Figure 2). Another artwork, by Anna Redko, depicts one of the leaders of the Belarusian protests, Maria Kolesnikova, in the poster “Motherland, Masha, Calls,” which evokes the World War II poster “Motherland calls.”Footnote 23 (See Figure 3). The historical image of the partisans was adopted by several groups representing the Belarusian IT community, which declared a “cyber partisan” war against the regime.Footnote 24

Figure 2. “Motherland is Calling,” Artwork by Vika Zhukovskaya, 2020.

Figure 3. Poster “Motherland, Masha, Calls” - art project by Anna Redko, 2020.

All these examples show just how potent the memory of World War II continues to be, supplying the symbolic means to represent the identity of the protesters and to reinforce the bonds of solidarity with the wider society. Used to create an assertive and powerful image of the protester pitted against the Lukashenka regime, these historical references, however, do not originate in the mnemonic repository developed by the Belarusian political and cultural opposition over the last few decades.Footnote 25 Paradoxically, they represent the Belarusian people by means of the symbolic apparatus devised by official ideology, with its emphasis on the active agency of the Belarusian people in the twentieth century.Footnote 26

Image of Victimhood

An important aspect of cultural memory that has contributed to the symbolic repertoire of the protest is linked to the attempt to process the experience of violence unleashed by Lukashenka against protesters. Juxtaposing images of SS solders dragging away weeping women with the Belarusian riot police doing the same in 2020 serve—in the posts circulating on social media—to expose the sheer brutality of the Lukashenka regime and to show just how alien it is to the Belarusian people. Another example compares the photograph of a protester at the moment of his release from a detention center with a screen capture from the legendary Belarusian film “Come and See” (1985), famous for its striking account of Nazi atrocities perpetrated in the occupied territories. (See Figure 4 and 5).

Figure 4. Protester released from the Akrestsina Detention Center in Minsk on August 14, 2020. Photo: Kseniya Halubovich

Figure 5. Screen Capture from the film “Come and See” (Mosfilm/Belarusfilm, 1985), dir. Elem Klimov

The reference frame associated with the memory of the Second World War has been combined with the memory of Stalinism, which has long served as a mnemonic marker of the political opposition.Footnote 27 On the 21st of August, borrowing the commemorative pattern of the Baltic Way, a human chain was organized by Zmitzer Dashkevich, the former leader of the youth branch of the Belarusian People's Front, Young Front, to connect the Kurapaty memorial site and the Akrestsina detention center.Footnote 28 The poster promoting this initiative posited a causal link between the crimes of Stalinism and the present-day violence: “…Kurapaty is the beginning of what we see today. Kurapaty and Akrestina are a single chain, and even symbolically, it is one road—Kurapaty at the beginning of it, Akrestina—in the end.”Footnote 29

A new initiative linking the Belarusian revolution with the political violence of the Soviet era took the form of “The Night of Executed Poets,” the commemorative event organized on October 29, 2020 in memory of the members of the Belarusian cultural elites who were arrested on that same day in 1937 and later killed by the NKVD. The commemoration took place in Kurapaty with the participation of actors from the Kupalauski theater, who had played a prominent role in the protests since August, as well as members of other groups that joined the protests, including academics, doctors, sportsmen, journalists, and students. Through their reading of the verses by poets who had died in Stalinist purges, the members of these various groups transformed the commemorative events into an act of diffusion of the mnemonic practices developed by the “old opposition,” thereby highlighting their broader political agenda within the protests.

Finally, the Sunday demonstration on November 1 was called the “March against terror,” or a march-requiem. Its finale was to be staged at Kurapaty, thereby not only reinforcing the historical association between the violence deployed by the Lukashenka regime and the Stalinist purges but also bringing to the memorial site a wide range of protest groups who had not previously taken part in the memory work of political opposition.

A broad range of intersecting and distinct social groups joined the protests in Belarus—from businessmen, IT professionals, doctors, women, and students, to academics, sportsmen, workers, and pensioners—thus facilitating incessant improvisation within the mobilization and demonstration scripts. By virtue of there being such a wide variety of actors engaged in contention, a process of re-signification of the cultural and political symbols and ideas was activated, leading to the formation of a blended socio-cultural imaginary, which served to integrate previously disconnected and competing projects and ideologies. Becoming a unique space of fluid social and cultural interactions, in which identities and meanings form, coalesce, and change, the Belarusian revolution is likely to achieve more than simply the removal of an autocratic ruler. In its aspiration to establish a new political order, it is tending to sweep away the rigid system of opposition that used to divide the country's cultural and political space. The oppositional discourse of nationhood consolidated around the remembrance of the victims of Stalinism has acquired an unprecedented societal appeal, as the protest event at the Kurapaty memorial site demonstrates. Remembering the victims of Stalinist crimes, however, does not convert into a full-scale “postcolonial othering” of the Soviet or the socialist legacy, as was the case in central and east European postcommunism, but has become one of the elements in the multi-directional system of historical and cultural references that shapes the identity of the protesters. The memory of Stalinist crimes informs the process of recounting the more recent experience of persecution and violence and, by doing so, it does not compete with but exists alongside the memory of the Nazi occupation. The components of the formerly-official discourse of the Belarusian nation have proved to be equally meaningful in the context of these protests, on account of their emphasis on the memory of the Great Patriotic War, which supplies the protesters with the heroic imagery needed to forge the assertive identity of activists who are set upon bringing down the Lukashenka regime.