Like other protest movements, the Belarusian one has often been approached in an instrumental-strategic mode, through a narrative about its tools or instruments and the goals and objectives according to which it can be said to have succeeded or failed. A related set of questions has been asked about what empowers people; how they acquire, or become aware of, their agency or political subjectivity; how they are transformed from passive bystanders to active participants and acquire new collective identities, such as the pluralist civic identity that has come to supplant the narrower ethnocultural subjectivity of the earlier Belarusian opposition.Footnote 1

Such questions are extremely important. In this short essay, however, I would like to enlarge our perspective. Beyond conditions of success or failure and binary distinctions between activists and bystanders, I propose to look at the regimes of engagement that give the Belarusian protests their distinctive style, and the ways in which this style develops in interaction with the material and technological environment.Footnote 2

Any protest movement will always exhibit a complex mix between different regimes of engagement: in addition to a strategic regime that treats the world as a source of resources and tools, there is also the familiar regime in which we feel at ease with our surroundings (until that ease is challenged, often violently). Such challenges often prompt exploration (yet another regime), making people look at their environment with new eyes. Finally, there is always the dimension of justification: moments of protest are also moments of intense civic debate about the common good—the values from which protest springs and not just the instruments required to fight for those values. Identifying how the different ingredients in the mix relate to each other can tell us much more about a protest (or any other social) situation than solely focusing on the interests and resources involved. Coordination in protest is not just about discussing who does what when in order to achieve a certain result. It is also about reconciling the claims of the different regimes of engagement that a situation calls for.Footnote 3

One frequent pathway begins with the familiar. It starts when those in power encroach upon our most intimate environment: in the most emblematic cases, on the human body itself and the objects that immediately extend it. The self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi in response to the confiscation of his vegetable cart and goods sparked the Arab Spring. The murders of Trayvon Martin, George Floyd, and other African Americans led to the Black Lives Matter movement. The initial victims become powerful symbols of protest that stand for countless similar encroachments experienced by numerous people; other symbols similarly stand for things held so dear that they hardly need to be articulated in words. The resulting protest movement then generates modes of engagement that are justificatory (debating the common good that is at stake), instrumental (looking for resources to mend the wrong), and exploratory (questioning old certainties about society and discovering new ways of relating to others). This dynamic has been in evidence in Belarus, where police brutality amplified the protests. I suggest, however, that the Belarusian case also exemplifies a reverse pathway: from the civic to new forms of familiarity. The rest of my essay explores these processes and their limits. In the first part I look at coordination and representation at protest events and in producing protest symbols such as flags. The second part discusses the role of Telegram and the emergence of local protest groups.

Protest and Coordination: Demonstrations and Protest Signs

One striking way in which the specific style of the Belarusian protests manifests itself is in interaction among protesters at those demonstrations. Let me briefly draw attention to three aspects of that interaction: the absence of rallies as culminations of protest marches; the language used by prominent figures in addressing protesters; and the materiality of protest signs.Footnote 4

The absence of rallies is a striking feature of the marches that have been the most prominent events of the protest wave. Its effect has been to foreground types of protest action in which all participants appear as equals: be it the many different kinds of marches (women, retirees, medics) or human chains such as the Chain of Repentance on August 21 that connected the Kurapaty Stalin-era execution site on the outskirts of Minsk with the detention center on Akrestsin Street where many protesters had been held and tortured.Footnote 5

This absence is in part due to the logistical difficulty of organizing rallies in the face of police reprisals that would make it impossible to set up the necessary equipment (such as a stage or microphones). Yet speaker meetings did take place as part of the protest wave, for example at factories or, in Hrodna, in the form of meetings with the mayor, and it would have been possible at least in some cases to have marches lead to the comparatively safe locations where such meetings were scheduled to take place. Thus the absence of a culminating event with speakers is at least in part a deliberate decision. This is noteworthy given the traditional choreography of public protest in post-Soviet countries, inherited from official political marches organized by the Soviet authorities and perpetuated by opposition movements including those active in Belarus prior to 2020.Footnote 6 A comparison with Russia may serve to illustrate the distinctiveness of this choreography. In the Russian case, the traditional miting model that implies a pre-selected group of prominent figures speaking from a stage has proven so pervasive that it was even replicated in the form on an opposition “online rally” during the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic in April 2020.Footnote 7 In Belarus, unlike Russia, even media images have largely acknowledged protesters’ status as agents in their own right rather than supporters of a leading figure.Footnote 8

This horizontal spatial structure of the Belarusian protests has been echoed in the way that the few widely recognizable figures, above all Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, Mariia Kalesnikava, and Veranika Tsapkala, have addressed protesters in their statements. Rather than assuming the right to speak for them by using first-person pronouns in the singular or plural, they constantly stress the agency of the protesters themselves by addressing them in the second person. Once again, the comparison with Russia is instructive. Contrast Mariia Kalesnikava's signature phrases “You are incredible” (Vy neveroyatnye—reformulated after the initial August 9 protests from her earlier “We are incredible”—My neveroyatnye) and “Belarusians, you are great” (Belarusy—vy molodtsy) with Russian opposition leader Aleksei Naval΄nyi's call-and-response slogan “Who is [or: wields] the power here? We are the power here” (Kto zdes΄ vlast΄? My zdes΄ vlast΄), repeatedly chanted at rallies.Footnote 9

Finally, this horizontality was also in evidence in many of the protest symbols and slogans displayed at the Belarusian protests. This concerned their content and symbolic meaning, but also their materiality and presentation.

As with other protest movements, much interest has focused on the language of the slogans. Thus, Siarhej Zelianko has classified Belarusian protest signs as expressing reasoning, self-evident truths, questions, messages, intentions, assertions, slogans, memes, quotes, self-identification, and demands.Footnote 10 What is striking here is that memes, wordplay, and other slogans striving to express individual originality are far from the dominant genre—unlike, for example, in the 2011–13 Russian protest wave.Footnote 11 Irony and persiflage are certainly in evidence (notably regarding Aliaksandr Lukashenka's reference to the protesters as “alcoholics, drug addicts, and prostitutes”). Yet the first weeks of protest in particular were striking in that most of the slogans on display were very basic and straightforward demands (“Stop the violence”—Spynitse hvalt). Thus instead of joining the protests as individuals striving for creative originality and engaging in self-expression, Belarusians were by and large taking to the streets as members of a civic community collectively voicing a specific set of ideas about the common good—if only to demand an end to violence and thus implicitly challenging a paternalistic model that sees violence as a legitimate instrument against trespassers threatening the social order.Footnote 12 The horizontal perspective of these kinds of protest, which crystallized around a basic set of principles and neutral symbols instead of rallying around a prominent figure, was also demonstrated through the use of protest paraphernalia. One example were the crowns that people used to self-inaugurate, thereby stressing that anyone has as much of a claim to the presidency as the self-appointed Lukashenka.Footnote 13

More important than the language of protest signs is their materiality. The individualism of the Russian and many other protest slogans has been encouraged by the ease of producing and displaying small signs in an era of home printers and smartphone cameras.Footnote 14 The Belarusian case is striking for the prominence of large, collectively-produced and -held banners on display at many rallies, but especially for the numerous huge white-red-and-white flags jointly sown, carried, or hoisted. Instructions and reports have widely circulated online.Footnote 15 Sympathetic observers have called this an “auxiliary” practice, but I would argue that it has been one of the most salient experiences of the protest wave.Footnote 16 Such activities involve a very basic form of practical coordination that goes far beyond the instrumental. From a symbol whose use was largely restricted to the political opposition, the flag has absorbed some of the most intense protest experiences and, in the process, become an object of (collective) familiar attachment—a common-place, in the terminology of pragmatic sociology.Footnote 17

Despite—or perhaps because of—their seemingly leaderless nature, the Belarusian protests have involved pragmatic forms of co-ordination at a very basic, material level alongside the purely individual, unattached form of participation characteristic of the 2011–13 Russian protests (which have also been in evidence in Belarus).Footnote 18 From street protest I now turn to the online dimension.

Reassembling Protest: From Viber to Telegram to Neighborhood groups

The rise of social media in political protest has been described as giving rise to a “personalization” of politics.Footnote 19 This observation needs to be nuanced, however. It would be simplistic to understand the “personalization” in question as a linear movement from politics as happening “up there” to politics as something “more personal.” Instead, I suggest that different new modes of communication imply—and format—different ways of being a person, or an individual. Thus “personalization” can mean involving the individual with some of her “non-public” attachments in a civic sphere where such attachments were previously considered out of place. Yet it can also mean reducing personal political engagement to the kinds of conventional categories built into the architecture of the social media in question: constraining emotional expression by offering a limited menu of emoticons or forcing people to express themselves as autonomous individuals whose relevant social relations are limited to the connections visible online. These observations form the background to my analysis of the use of social media in Belarusian protest.Footnote 20

Since the beginning of the protest wave, much attention has focused on the role of Telegram, a messaging app that is often described as one of the central “drivers” or “tools” of post-election protest in Belarus.Footnote 21 Its significance as a communication platform for Belarusian protesters is often placed into the context of Telegram's use by those in other countries, from Russia to Iran to Hong Kong.Footnote 22 There are also those who point to Telegram's deliberate gestures toward Belarus, particularly the open support of the Belarusian protesters expressed by its Russian founder, Pavel Durov, in his statements and in symbolic gestures such as changing the Belarusian flag emoji from red-green to white-red-and-white.Footnote 23

To better understand the role of Telegram, however, it is worth noting that its prominence in Belarus was unexpected given the previous dominance of Viber, a messaging app that is even more widespread in that country. Co-designed by a Belarusian programmer in 2010 and, until August 2020, maintaining large offices in Minsk and Brest, Viber quickly became the most widely used messaging app in Belarus (and Ukraine), with a market penetration of 70% by early 2020 and a quasi-monopolistic role in everyday smartphone-based communication.Footnote 24 As late as 2019, Telegram ranked only fourth among messengers in Belarus.Footnote 25

Why did Viber not wield a greater significance in the Belarusian protests? One answer is instrumental: Viber is widely seen as offering less anonymity than Telegram; users’ phone numbers and even their networks of contacts are viewed as easy to trace even though the content of communication is protected by end-to-end encryption.Footnote 26 This explanation, however, assumes that all protesters want to remain anonymous. While obviously true in some respects given the threat of brutal police retaliation, this also goes against innumerable examples of Belarusians deliberately protesting without concealing their identity, whether by taking part in public demonstrations, displaying protest symbols from their windows, or posting texts and photos in non-anonymous social media. Another answer points to the role of young people and popular bloggers as early adopters whose key role in the pre- and post-election protests helped Telegram's spread.Footnote 27 That begs the question of why bloggers used Telegram in the first place.

A different explanation is that Viber is largely associated with everyday practical concerns: Viber chats are typically used by groups of friends, members of the same family, residents of the same building, or parents of school classmates. Tellingly, Viber is much more popular among women, traditionally in charge of organizing family life.Footnote 28 Attempts to use these existing chats to coordinate protest were often met with resistance by some participants, who insisted that their day-to-day concerns be kept separate from “politics.”Footnote 29 That separation is itself highly indicative of the type of protest that we are seeing in the Belarusian case. It means that, rather than growing organically out of everyday practice and communication, protest is experienced as a separate sphere of engagement, no matter how closely people's disaffection with Lukashenka is rhetorically tied to everyday problems. The contrast between Viber and Telegram as environments of protest communication is the electronic equivalent of the contrast between protest based on existing community structures and one that mobilizes activists individually regardless of their involvement in such structures. The further move from nationwide, city-level, or functional (drivers’ or financial aid) Telegram protest channels to those involving the residents of a single neighborhood or building (and, in some cases, running parallel to existing Viber groups) is in some ways tantamount to reassembling community from the top down as a result of protest; more on this below.

Thus what we are witnessing in the Belarusian case is a type of collective action dominated by the civic regime of engagement, corresponding to a certain ideal of a civil sphere into which people step to discuss matters of public concern, with their personal loyalties and other attachments forming no more than their “background.” This ideal is so ingrained in modern theories of protest and civil society that other types of pathways from the private to the public are implicitly treated as imperfect or deficient.Footnote 30 It is worth considering, however, how differently the structure of Belarusian protest might have turned out if it had grown organically out of existing structures—or, conversely, what it says about Belarusian society that such structures did not become fertile ground for protest.

With this in mind, let us now turn to the dynamics of Telegram use in Belarusian protest.

Much international attention has focused on nexta_live (pronounced Nekhta, Belarusian for “someone”), the opposition channel run from Poland by 22-year-old Stepan Putilo which, due to its importance in the protests, became the most widely-subscribed Russian-language Telegram channel in the world within just over a week after August 9.Footnote 31 By providing live reporting from the major protest events and guidance to protesters in the form of recommendations and agendas, nexta_live became one of the principal sources of information for protesters and outside observers alike. Other Telegram channels with a nationwide perspective also saw a huge rise in the number of subscribers.Footnote 32

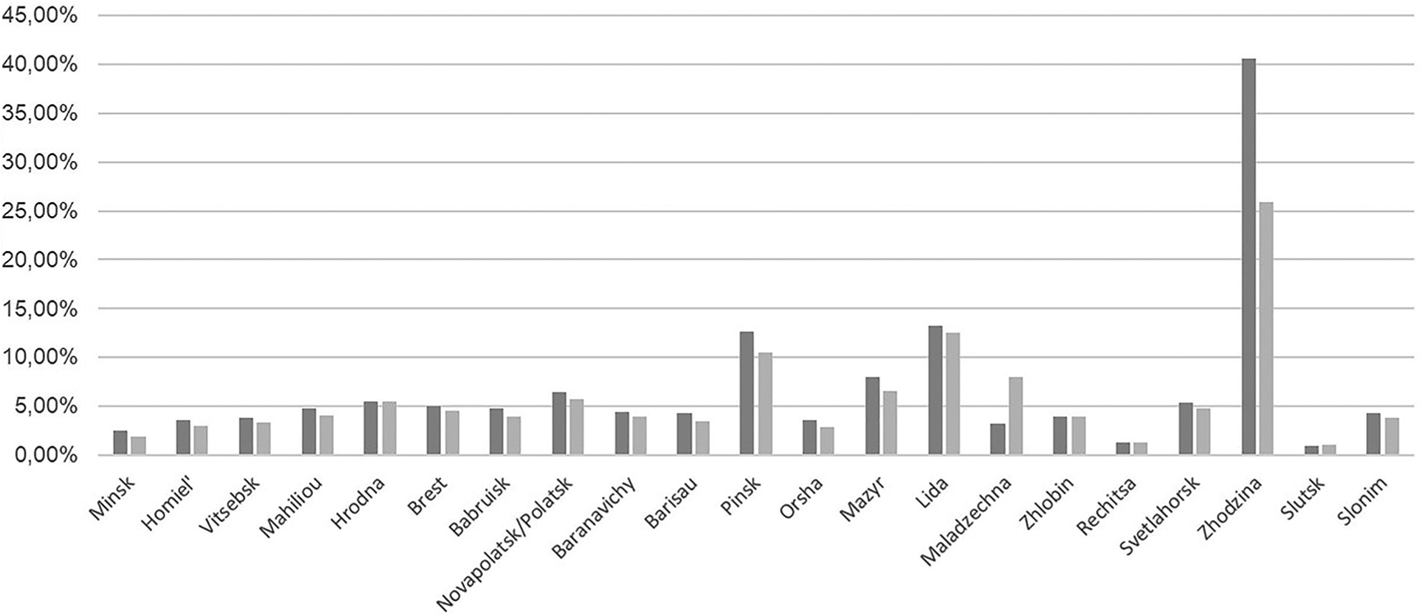

While such channels, with their primary focus on events in Minsk, gained a wide audience both inside Belarus and beyond its borders, it is important to note that channels with a regional or local focus—where people could find information about protests in their own city—also quickly became popular. In eleven out of the twenty largest Belarusian cities, by August 21 local Telegram protest channels had a number of subscribers equivalent to 3.5 and 5.5 of their total population (see Figure 1).Footnote 33

Figure 1. Subscribers to local protest channels or chats in Telegram in the twenty largest cities, August/October 2020.

And while that percentage was lower in three cities (including Minsk, which was already “covered” by the generic protest channels such as nexta_live), five cities actually had significantly higher figures: from just over 8 percent for Mozyr΄, in the Homel΄ region, to a massive 40.59 percent in Zhodino, the latter likely due to the nationwide attention attracted by the protest gatherings at the BelAZ dump truck plant located there. By mid-October, the numbers had somewhat receded almost across the board. One reason for this, reported by subscribers, was that local channels increasingly took to reposting information from news outlets and national channels and thus lost some of their specific appeal. Another reason, however, was the growth of more specialized chat groups (such as for medics or retirees) or local ones, in both Telegram and Viber, that operated at the level of neighborhoods or even individual buildings.Footnote 34

The neighborhood groups coordinated a wide variety of activities. Some (such as flag hoisting) were directly protest-related; others (such as proposing designs for a neighborhood flag, or organizing courtyard lectures on Belarusian history) grew out of protest but went beyond it; others still drew on the communities newly emerging from protest to discuss matters of everyday concern, such as building maintenance and protection against Covid-19. The attention devoted to each of these topics varies considerably, however. Oksana Shelest, who performed a quantitative analysis of the content of approximately 1,000 local chats, found that 40% of messages had to do with coordinating protest activities, though only an unspecified portion of those were about local (rather than national or city-wide) protest.Footnote 35 That number dropped even further by December, as coordination largely moved out of publicly accessible chats due to security concerns.Footnote 36 A further 25% were devoted to “general communication” (obshchenie), of which only a small fraction had to do with non-protest related practical concerns.Footnote 37 A significant share of the content was devoted to general discussion of the political situation.

Unlike participation in city-level groups, activity in the local chats displayed far greater disparities between Minsk and provincial cities, and between regions.Footnote 38 These disparities were visible not only on the level of online chats but also concerning the courtyard get-togethers that were organized with the help of some of these chats. One factor in this was swifter repression in some parts of the country.Footnote 39 Urban architecture was a factor that contributed to replicating these disparities within cities. Some city districts had high levels of both online and offline activity, occasionally giving rise to meeting spots of city-wide significance such as Minsk's famous Ploshcha Peramen (Square of Changes). In other districts such activity was much lower. As architect Dmitry Zadorin noted, in Minsk the widely celebrated courtyard gatherings could only take place in the relatively small proportion of residential buildings that actually have courtyards.Footnote 40

A New Subjectivity? Yes, but What Kind?

This brief essay has touched upon some of the events, objects, and situations that have given the Belarusian protests their distinctive style—from marches to flags and from Telegram groups to courtyard gatherings. My observations suggest that this protest environment has not grown organically out of previous everyday activities. Be it flag-making practices, communication at protest marches and in online groups, or courtyard get-togethers, most represent a radical break rather than a natural extension of existing habits and spheres of familiar engagement to respond to new challenges. Some protest activity has involved rallying around existing common-places (such as singing well-known songs), but most has been predicated upon discovering or producing new practices.

This seems to confirm that protest has given rise to a new subjectivity. It is less clear, however, whether and how that new subjectivity might also affect everyday life beyond the protests themselves, regardless of changes to the political system. Will protests spill over into new ways of organizing local communities, creating new solidarities that will express the new-found subjectivity on a practical level, or will the inevitable end of the protest cycle signal an end to practices viewed as pertaining only to protest? Some evidence points to the former: activities such as collective flag-making create deep engagements that will firmly establish the symbols of protest as much more than transitory insignia; the marches, local chat groups, and courtyard gatherings have created new horizontal connections. Other signs suggest a more cautious interpretation: despite the impressive collective enthusiasm and determination, it appears that Belarusians largely continue to view politics as a sphere that is separate from their everyday lives rather than growing out of everyday concerns. The Belarusian protests are already momentous; whether or not they will lead to deeper social transformation remains to be seen.