Introduction

Multiple biotic and abiotic issues threaten the future of banana production (Ramirez et al., Reference Ramirez, Jarvis, Van den Bergh, Staver and Turner2011; Ploetz and Evans, Reference Ploetz, Evans and Janick2015), the potential consequences of which will likely have a large impact on the nutrition and livelihoods of many millions of people (Ploetz et al., Reference Ploetz, Kema and Ma2015). The limited gene pool of clonal crops like bananas (Perrier et al., Reference Perrier, De Langhe, Donohue, Lentfer, Vrydaghs, Bakry, Carreel, Hippolyte, Horry, Jenny, Lebot, Risterucci, Tomekpe, Doutrelepont, Ball, Manwaring, de Maret and Denham2011) means they have evolved little resistance to many pathogens, making them particularly vulnerable (Strange and Scott, Reference Strange and Scott2005; McKey et al., Reference McKey, Elias, Pujol and Duputie2010). Thus, there is urgent need for the genetic resources present in banana crop wild relatives (CWRs) (Musa L. spp.) to be conserved and made available to breeders (Dempewolf et al., Reference Dempewolf, Baute, Anderson, Kilian, Smith and Guarino2017).

Storing and accessing genetic resources as seeds is an efficient method for ex situ conservation (Li and Pritchard, Reference Li and Pritchard2009; Convention on Biological Diversity, 2012; FAO, 2012; Laliberté, Reference Laliberté2016). The management of seed genetic resources requires their routine germination for viability monitoring (FAO, 2014), as does accessing plants for phenotyping or breeding; for bananas, low and inconsistent germination rates are a considerable limitation to these (Laliberté, Reference Laliberté2016; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Tumuhimbise, Amah, Uwimana, Nyine, Mduma, Talengera, Karamura, Kuriba, Swennen, Campos and Caligari2017). Improvement in the ability to germinate banana seeds will therefore have important applications for food security and plant genetic resources conservation (Panis et al., Reference Panis, Kallow, Janssens, Kema and Drenth2020).

There are around 80 species in the genus Musa (Govaerts and Häkkinen, Reference Govaerts and Häkkinen2006); cultivated bananas mostly derive from two of these: Musa acuminata Colla and Musa balbisiana Colla (Boonruangrod et al., Reference Boonruangrod, Desai, Fluch, Berenyi and Burg2008; De Langhe et al., Reference De Langhe, Vrydaghs, De Maret, Perrier and Denham2009; Perrier et al., Reference Perrier, Bakry, Carreel, Jenny, Horry, Lebot and Hippolyte2009, Reference Perrier, De Langhe, Donohue, Lentfer, Vrydaghs, Bakry, Carreel, Hippolyte, Horry, Jenny, Lebot, Risterucci, Tomekpe, Doutrelepont, Ball, Manwaring, de Maret and Denham2011). Overall, M. acuminata is the most important contributor of genetic material for cultivated bananas (Raboin et al., Reference Raboin, Carreel, Noyer, Baurens, Horry, Bakry, Montcel, Ganry, Lanaud and Lagoda2005; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Cardi, Sarah, Ricci, Jenn, Fondi, Perrier, Glaszmann, D'Hont and Yahiaoui2020); for instance, they are the sole contributor to the Cavendish group which accounts for approximately 47% of global production (FAO, 2019). There are ten accepted subspecies (used hereafter to also include varieties and subspecies) of M. acuminata (Govaerts and Häkkinen, Reference Govaerts and Häkkinen2006), which are distributed in Asia, northern Australasia and Melanesia (Perrier et al., Reference Perrier, Bakry, Carreel, Jenny, Horry, Lebot and Hippolyte2009).

In contrast to M. balbisiana (McGahan, Reference McGahan1961a, Reference McGahan1961b; Stotzky et al., Reference Stotzky, Cox and Goos1961, Reference Stotzky, Cox and Goos1962; Stotzky and Cox, Reference Stotzky and Cox1962; Bhat et al., Reference Bhat, Bhat and Chandel1994), surprisingly little attention has been paid to M. acuminata seeds. In the 1950s, Simmonds (Reference Simmonds1952, Reference Simmonds1959) examined both M. acuminata and M. balbisiana with various non-invasive treatments (looking at ripeness, maturity and moisture content) and invasive treatments (using chipping, scorching, soaking and acid treatments). The physical permeability of M. acuminata seed coats to water has received most attention but still remains unresolved (Darjo and Bakry, Reference Darjo and Bakry1990; Wattanachaiyingcharoen and Turner, Reference Wattanachaiyingcharoen and Turner1990; Fortescue and Turner, Reference Fortescue, Turner, Pillay and Tenkouano2011; Puteh et al., Reference Puteh, Aris, Sinniah, Rahman, Mohamad and Abdullah2011). Significantly, the thermal requirements for germination of M. acuminata seeds have not been investigated.

Musa spp. are tall forest herbs of tropical to subtropical forests. Their inflorescences are pollinated by bats, birds and probably insects (Itino et al., Reference Itino, Kato and Hotta1991; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Li, Wang and Kress2002), and seeds are dispersed by bats, birds and mammals (Ge et al., Reference Ge, Liu, Wang, Schaal and Chiang2005; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Cao, Sheng, Liang and Zhang2005, Reference Tang, Sheng, Ma, Cao, Parsons, Ma and Zhang2007; Marod et al., Reference Marod, Pinyo, Duengkae and Hiroshi2010). They are observed in disturbed sites such as farm or plantation edges, craggy cliffs and steep mountain gullies, or roadside and track edges. Specifically, M. acuminata is known to colonize and dominate disturbed sites (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Tang, Shi and Bai2000; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Zhang, Bai and Tang2002; Meng et al., Reference Meng, Gao, Chen and Martin2012). Musa are therefore widely recognized as disturbance-adapted ‘jungle weeds’ (Simmonds, Reference Simmonds1959).

Several adaptations may be expected in M. acuminata seeds to facilitate germination following disturbance. Firstly, an environmentally regulated gap detection mechanism may stimulate germination immediately following disturbance and, conversely, prevent germination prior to disturbance (Raich and Khoon, Reference Raich and Khoon1990; Vázquez-Yanes and Orozco-Segovia, Reference Vázquez-Yanes and Orozco-Segovia1993). For larger-seeded disturbance-adapted species, germination may be stimulated by changes in micro-climate temperature (Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Burslem, Mullins and Dalling2002; Aud and Ferraz, Reference Aud and Ferraz2012). This may involve changes in diurnal temperature fluctuations, as soil is exposed to sunlight when a canopy gap forms and therefore warming and cooling fluctuations are altered (Vázquez-Yanes and Orozco-Segovia, Reference Vázquez-Yanes and Orozco-Segovia1982; Aud and Ferraz, Reference Aud and Ferraz2012; Poschlod et al., Reference Poschlod, Abedi, Bartelheimer, Drobnik, Rosbakh, Saatkamp, van der Maarel and Franklin2013; Jaganathan, Reference Jaganathan2018). Sensitivity to differences in alternating temperature range plays an important role in limiting seedling loss during unfavourable conditions (Kos and Poschlod, Reference Kos and Poschlod2007; Saatkamp et al., Reference Saatkamp, Affre, Baumberger, Dumas, Gasmi, Gachet and Arene2011). Secondly, the hard seed coat of Musa spp. may limit imbibition and delay germination by physical dormancy. This may be relieved according to environmental factors in relation to disturbance, including temperature and moisture regimes, as well as changes in the ecological community such as predators and dispersers. Alternatively, after-ripening or stratification (a pre-treatment period between dispersal and germination) may delay germination immediately after dispersal as observed for some seeds of tropical rainforests (Vázquez-Yanes and Orozco-Segovia, Reference Vázquez-Yanes and Orozco-Segovia1993, and references therein).

The aim of this study is to test hypotheses that M. acuminata seed germination is regulated in accordance with expectations of disturbance-adapted tropical species. In particular, we focus on germination responses to temperature, including diurnally alternating temperature regimes as a mechanism for gap detection. Therefore, we (1) describe the morphology and mass of the seeds used in this study, (2) assess whether seed coats are permeable to water, (3) investigate optimal temperature regimes for seed germination, (4) investigate whether stratification relieves dormancy, and finally (5) evaluate the optimal temperature regimes from our germination tests against the macro-climate temperatures of wider distributions of the subspecies under investigation. However, because the seeds used in this study have undergone processes which may influence behaviour, namely drying and sub-zero temperature storage (Baskin et al., Reference Baskin, Thompson and Baskin2006), a true definition of germination and dormancy class is not possible, but rather the aim is application to seed conservation.

Materials and methods

Plant material

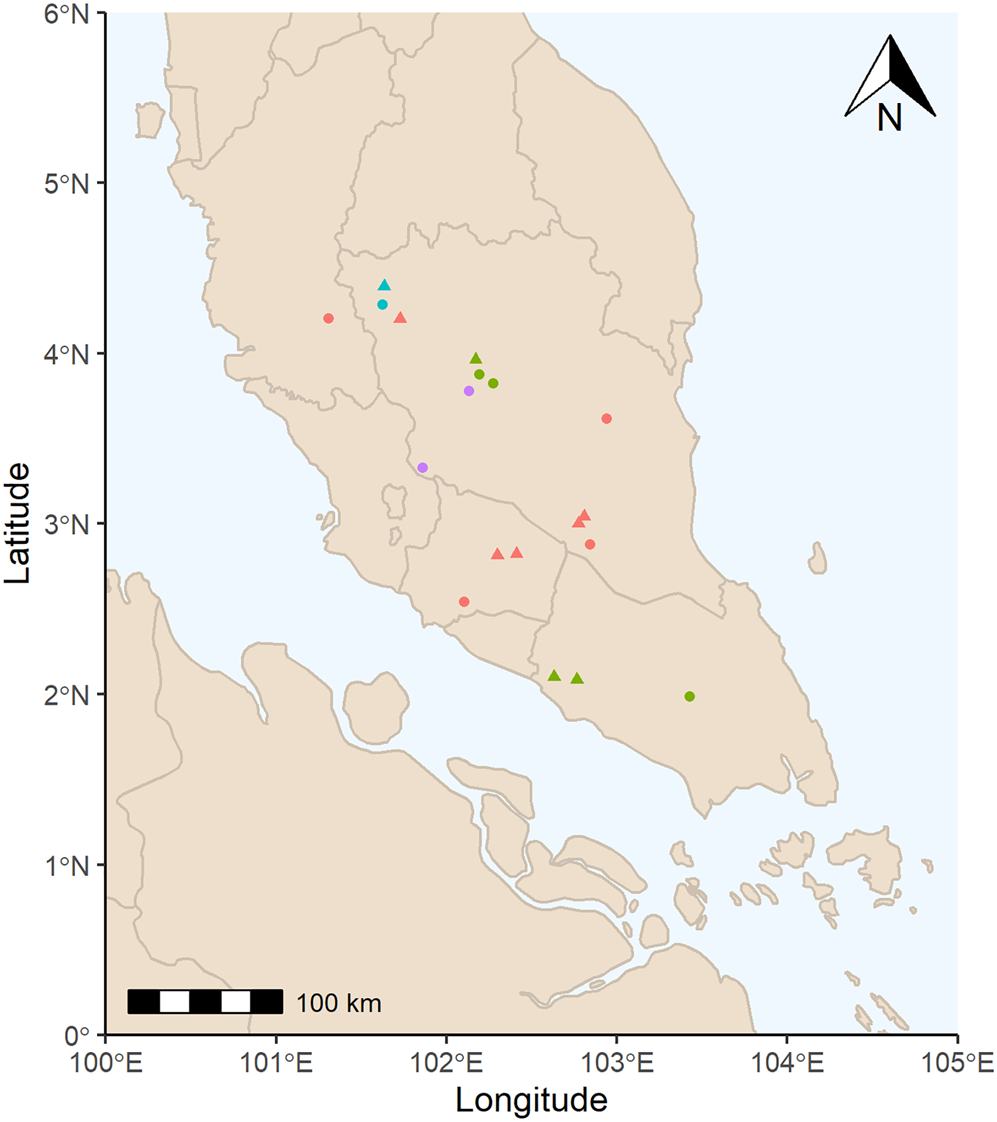

Nineteen seed accessions of four M. acuminata subspecies were used for the initial viability assessment (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Following the viability assessment described below, nine of these accessions, which consist of three subspecies, were selected for a series of experiments (M. acuminata subsp. acuminata, M. acuminata subsp. malaccensis and M. acuminata subsp. microcarpa; Fig. 1 and Table 1). Seeds were collected from ‘Malaysian peninsular rainforest’ and ‘montane rainforest’ ecoregions in the ‘tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forest’ biome (Olson et al. Reference Olson, Dinerstein, Wikramanayake, Burgess, Powell, Underwood, D'amico, Itoua, Strand, Morrison and Loucks2001). Mean annual temperature and mean annual precipitation at the collecting locations are 26.4 ± 0.7°C and 2332 ± 342 mm (mean and standard deviation), respectively (Fick and Hijmans, Reference Fick and Hijmans2017). Seeds were collected in 2015 and 2016 and provided to the Millennium Seed Bank (MSB) by the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute.

Fig. 1. Collecting locations of M. acuminata seed accessions. Red = M. acuminata subsp. acuminata, green = M. acuminata subsp. malaccensis, blue = M. acuminata subsp. microcarpa, purple = M. acuminata subsp. truncata; triangles = selected accessions following viability assessment, circles = accessions not selected. Collection points adjusted to reduce overlap.

Table 1. M. acuminata seed accessions selected for use in germination tests

The full set of accessions used for viability testing is in Supplementary Table S1. Date donated is accessioning date on arrival at the MSB.

Seeds derive from one or two plants per accession. Populations were wild in origin and occurred either in secondary rainforest, or oil palm/orchard plantation edges. Bunches were only collected from light green to yellow fruits. Fruits from unhealthy or injured plants were avoided. Cut tests were carried out at the time of collection to assess seed maturity, and only bunches with mature seeds were collected. Seeds were considered mature if the endosperm was dry and powdery, as opposed to wet or milky, and embryos were well developed with a mushroom-like capitate shape. Seeds were extracted by hand from ripe fruit on return to the laboratory, and the pulp containing seeds was washed thoroughly using running tap water and sieves, until all the flesh was removed. Unripe fruits were left in the laboratory at room temperature (~25°C) to ripen until they began to yellow and soften and then seeds were removed in the manner described above. After extraction, seeds were air-dried in the laboratory at room temperature and then further dried in a large sealed plastic drum containing silica gel to a maximum of 25% equilibrium relative humidity (eRH). Seeds were then packed in sealed aluminium envelopes and stored for an average of 6 months at 4°C until air shipped to the MSB. On arrival at the MSB seeds were further dried at 15% eRH and 18°C in a dry room to approximately 7% moisture content. Seed mass of dried seeds was measured by weighing five replicates of 50 seeds. Seeds were then sealed in airtight glass containers and stored at −20°C for 12–18 months prior to use in this study. Before use, selected accessions were removed from cold storage for at least 24 h to equilibrate to 18°C in a dry room at 15% relative humidity (RH). Morphological observations were recorded by dissecting ten seeds per accession and inspecting using a binocular microscope. Seed mass was measured using five samples of 50 seeds.

Viability

Post-storage seed viability was assessed using two methods to improve estimation methods for this and future studies. The first method was the tetrazolium chloride test (TTC), following the approach of Leist and Krämer (Reference Leist and Krämer2011). Seeds were imbibed on agar for 3 d at 20°C. Then, a proportion of the testa was removed using a scalpel on two lateral sides to expose the endosperm. Seeds were then soaked in 1% buffered 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (pH6–8) for 2 d at 30°C in the dark. Staining patterns were then recorded. Embryos that completely stained dark red, or that showed dark red staining at the embryonic axis were considered viable; light pink staining or white embryos were considered unviable. Fifty seeds per accession were tested.

Secondly, embryo rescue (ER) was carried out as a viability test. In a laminar flow, seeds were sterilized by soaking them in 96% ethanol for 3 min, followed by soaking in 1% NaOCl (diluted commercial bleach 5% containing one drop of detergent per 100 ml) for 20 min. Seeds were then rinsed three times in sterilized water. Continuing in the laminar flow with sterile forceps and scalpel, embryos were extracted from seeds. This was done using an incision in the seed coat next to the micropyle and manipulating the seed in order to split the testa, the embryo was then gently removed. Embryos were subsequently transferred onto autoclaved half MS medium (Murashige and Skoog, Reference Murashige and Skoog1962) in tubes using long forceps with the haustorium in contact with medium and the embryonic axis upwards. Tubes containing embryos were incubated in the dark at 27°C for 14 d after which they were put in a growth chamber in the light at 27°C for an additional 14 d. Six possible observations were recorded: shoot, callus, blackened colouration, contamination, no change or no embryo as observed during extraction. Ten seeds per accession were tested.

Imbibition

Seed coat permeability to moisture was tested by assessing mass change of dry seeds during imbibition. Seeds were either left intact and incubated at 25°C, or scarified by removing a sliver of lateral seed coat with a scalpel in order to expose the white seed endosperm (3.36 ± 1.35 mg) and incubated at 25°C, both with a 12 h light/dark regime. To imbibe seeds, they were placed on agar with the micropyle in contact with 1% agar in Petri dishes (100 × 150 mm). Seeds were weighed individually on days 0, 1, 2, 5, 7 and 21. Prior to measurement, surface moisture and agar were blotted off with tissue paper. Twenty-five seeds from accession M. acuminata subsp. malaccensis (882899) were used for each treatment. This accession was selected because it had the most seeds. The increase in mass percentage was calculated individually for each seed and plotted against time in order to estimate equilibrium.

Germination and temperature

Nine accessions were selected for germination tests based on adequate viability and availability (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). Incubator temperature regimes were based on the climate at the location of collection. Temperatures were extracted from WorldClim version 2.0 (Fick and Hijmans, Reference Fick and Hijmans2017) using seed accession collection coordinates to extract climate data at 30 arc seconds resolution. The collecting locations’ mean monthly temperature to the nearest 5°C was selected for a constant incubation regime: 25°C; whilst alternating temperatures were based on the monthly maximum and minimum temperatures where the upper temperature was rounded both up and down: 35/20 and 30/20°C. Minimal temperature seasonality occurred in the climate data for the collecting sites (mean coefficient of variability 1.81 ± 0.16), so no seasonal differences were included in the design.

Seeds were placed on moist sand (100 g fine silica sand and 14 ml of deionized water) in sealed square plastic boxes (100 × 100 × 20 mm) which were then sealed in clear plastic sealable bags to minimize moisture loss and contamination. These were then placed in the corresponding incubators with 12 h at each temperature. Photoperiod was also on 12 h cycles, light was during the warmer period and darkness during the cooler; light quantity was approximately 7 μmol m−2 s−1. Twenty-three to fifty-three seeds were used in one to three replicates per accession. Sample sizes were constrained by limited seed availability. Germination tests were scored every 7 d, and tests were continued for 6 months to account for potential long sporadic germination times previously observed and to ensure reasonable maximum germination. Germination was defined by radicle emergence. Germinated seeds were removed at scoring.

Thermogradient

For one accession of M. acuminata subsp. malaccensis (accession 882899) (the accession with the most seeds), 25 temperature regimes were tested using a thermogradient plate (GRD1, Grant Instruments Ltd, Cambridge, UK). All combinations of constant and alternating temperatures from 15 to 35°C with an interval of 5°C were used. An additional six temperature regimes were tested in incubators to 40°C, with all combinations of 15–40°C under 5°C temperature intervals. Temperature was cycled on a 6/18 hourly basis to allow for a comparison of short and long periods at the warmer/cooler part of the cycles estimated from local temperature data (Meteoblue, 2020). Accordingly, for each temperature regime, there was a sample that had the hotter temperature at 6 h and one at 18 h, except for the samples at 40°C which only had the hotter temperature for 6 h because of a limitation of incubators. Incubation was carried out in the dark because light could not be controlled differently in the thermogradient plate for the short and long cycles, and seeds were previously observed to germinate in the dark. For each condition, 30 seeds were placed on 10 g of silica sand with 8 ml of deionized water in a circular Petri dish (100 × 15 mm), and dishes were sealed with film to avoid moisture loss. An additional 1–2 ml of water was added if the colour of the sand lightened due to water loss. Tests were scored in daylight every 7 d. These germination tests were continued for 70 d.

Germination and pre-treatment

To simulate the transition of seeds in the soil seed bank before and after gap formation, seeds were incubated (‘stratified’) at constant 25°C and then moved to alternating 30/20°C after 3 months. There were two levels of stratification at 25°C, seeds were either placed on moist sand as described above (at 100% RH), or suspended in sealed jars over lithium chloride solutions controlled to be at 60% RH (60 g LiCl in 200 ml deionized water), for these a humidity meter was placed into the jar with the seeds for 7 d to ensure the correct RH. After 3 months, seeds were then incubated for three further months at 30/20°C light/dark as previously described. Scoring of germination tests was carried out as previously described. All germination tests were carried out at the MSB.

Macro-climate assessment

We composed a dataset of occurrence records of wild M. acuminata subspecies from 16 sources including recent field missions (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Table S2). Accurate locality descriptions without coordinates were georeferenced using Google Earth pinpoints (Google Earth, 2018). Duplicate records, outliers and zero coordinates were detected and removed with the online tool CoordinateCleaner (Zizka et al., Reference Zizka, Silvestro, Andermann, Azevedo, Duarte Ritter, Edler, Farooq, Herdean, Ariza, Scharn, Svanteson, Wengstrom, Zizka and Antonelli2019). This resulted in a dataset consisting of 222 occurrence records of nine (of the ten) M. acuminata subspecies. Coordinates from these were used to extract temperature-related bioclimatic data from WorldClim version 2.0 (Fick and Hijmans, Reference Fick and Hijmans2017) to compare to the optimal germination temperatures from the previous germination tests, and to look for variation between subspecies. Additionally, precipitation across subspecies distributions was extracted to assess further climate variation by taxa.

Statistical analysis

Seed mass increase during imbibition was plotted against time, and a point was selected where equilibrium with the environment was reached across treatments. Percentage mass increase at this point for the two treatments was compared using a two-sample t-test. Descriptive indices were calculated for the germination data in the R package GerminaR (Isla et al., Reference Isla, Alfaro, de Santana, Ranal and Pompelli2019). These included germination percentage (Labouriau and Valadares, Reference Labouriau and Valadares1983), mean germination rate defined as the reciprocal of the average time to germination (Ranal and Santana, Reference Ranal and Santana2006), mean time to germination (Czabator, Reference Czabator1962) and synchrony index (Primack, Reference Primack1980; Ranal and Santana, Reference Ranal and Santana2006). Generalized linear models (GLMs) were made to analyze final germination with binary responses. Models had quasibinomial error structure (to account for overdispersion) and logit link functions. Overdispersion of models were assessed by simulating residuals from the fitted models and comparing the standard deviation of the simulated and actual data using the DHARMa package in R (Hartig, Reference Hartig2019). Maximum models, with fixed factors of accession, subspecies, viability and a random factor of temperature treatment, were fitted. Minimum adequate models were achieved by removing factors according to ANOVA and Chi-squared tests. Post hoc contrast analysis was carried out between treatments and controls using multiple comparisons of means and Tukey contrasts. In all cases, effective sample sizes were used which corrected sample sizes according to the viability estimates from the TTC test result. This viability measure was used because it was not possible to correlate the two viability measures (ER and TTC) and the sample size used in the TTC was greater than for ER (50 rather than 10 seeds). All statistical analysis was carried out using R v 3.6.0 (R Core Team, 2019).

Results

Morphology and seed mass

Observations showed that M. acuminata seeds have two chambers within a two-layer integument (Fig. 2A). The larger first chamber contains the embryo and endosperm. Embryos are undifferentiated and capitate, 1–2 mm in size and the embryonic axis extends into the micropylar collar (Fig. 2B). The cotyledonary haustorium of the embryo extends below the embryonic axis and is surrounded by a powdery white endosperm. Above the embryo is a micropyle, which is filled by a micropyle plug and forms an operculum. The second chamber consists of a chalazal mass. Seed mass was 40.45 ± 6.80 mg (mean and standard deviation, used from hereon).

Fig. 2. (A) Longitudinal section of a M. acuminata seed, showing micropyle (mi), embryo (em), chalazal mass (ch) and endosperm (en). (B) Detail showing micropyle cap (mi-cap), micropyle channel (mi-ch), haustorium (hau), inner integument (int) and outer integument (out). Image taken with Keyence VHX5000. Images: S. Kallow.

Viability

Viability was 49 ± 28% according to the TTC test and 28 ± 29% for the embryo recue (i.e. the ‘shoot’ category; Supplementary Table S1). No linear relationship could be found between the two parameters of viability (r 2 = 0.055, P = 0.811). Embryos that did not germinate mainly remained white (Supplementary Fig. S2). This means that viability was low because embryos were most likely dead, rather than infested by insects, fungal/bacterial contaminated or lacking embryos. The combined results of the viability tests allowed us to select the nine accessions used for germination tests.

Imbibition

During imbibition, both scarified and non-scarified seeds rapidly increased mass in 1 d and reached equilibrium after 5 d or earlier (Fig. 3). The difference in percentage mass increase was not statistically significant between scarified (49.6 ± 11.8%) and non-scarified seeds (53.3 ± 8.7%, two-sample t-test, t = 1.1189, df = 33.145, P = 0.27). The moisture content of non-scarified seeds increased from 7% on day 0 to 36% after 21 d imbibition.

Fig. 3. Increase in seed mass of scarified and non-scarified M. acuminata subsp. malaccensis seeds during imbibition from 7 to 36% moisture content. Seeds weighed individually (n = 25). Bars represent standard deviation.

Germination and temperature

Seeds germinated to higher levels at alternating temperatures compared with constant temperature (Table 2 and Fig. 4). Optimal germination was at 35/20°C (P = 0.006) followed by 30/20°C (P = 0.031) compared with constant temperature at 25°C; however, there was no significant difference between 35/20 and 30/20 (P = 0.164) following multiple comparison of means using Tukey contrasts. The minimum adequate GLM included only treatment temperatures, as germination was highly variable between accessions in all tests. Mean time to germination under optimal temperature (35/20°C) was 56 d, and this was highly variable (±39 d).

Fig. 4. Final germination percentages after 6 months incubation at different conditions for nine M. acuminata accessions (subsp. acuminata, malaccensis and microcarpa). (A) Alternating temperature regimes compared with control of constant temperature (30/20, P = 0.031; 35/20, P = 0.006). (B) Pre-treatment for 3 months at 25°C (60% RH, P = 0.007) prior to incubation for 3 months at 30/20°C. Incubation was on moist sand (100% RH) unless otherwise stated. Alternating temperatures (30/20 or 35/20°C) were on 12 hourly cycles. Stars indicate P-values (* = <0.05, ** = <0.01) from a GLM with quasibinomial error structure and logit link using the number of seeds germinated and the number of seeds that did not germinate, against the control. Final germination percentages are corrected to take into account viability assessment with previous TTC test (n = 23–53 seeds in 1–3 replicates).

Table 2. Indices from germination results from selected M. acuminata accessions

Germination time is mean time to germination in days (Czabator, Reference Czabator1962), germination rate defined as the reciprocal of the average time to germination (Ranal and Santana, Reference Ranal and Santana2006), and synchrony index define by Primack (Reference Primack1980) and Ranal and Santana (Reference Ranal and Santana2006). Alternating temperatures were for 12 h thermo and photo cycles. Germination tests were continued for 6 months. Results were corrected to take into account viability assessment with previous TTC test (n = 23–53 seeds in 1–3 replicates).

a Pre-treated by incubation at constant 25°C at two levels of RH for 3 months prior to 30/20°C incubation for 3 months at 100% RH.

b Incubated only at constant 25°C.

Thermogradient

Maximum germination occurred equally at 35/25°C (6/18 h) and 35/30°C, followed by 30/20°C (90 and 40%, respectively; Fig. 5). No germination occurred at any constant temperature, or at temperatures below 20°C. There was no germination when the higher temperature was for the longer period (18 h), apart from at 30/35°C. In the GLM, only the short hotter temperature had a significant positive effect on the number of seeds germinated (P < 0.001), and all other parameters (long temperature, the average temperature or the temperature differential) could be removed from the model without reducing the explanatory power.

Fig. 5. Contour plot of final germination percentage for M. acuminata subsp. malaccensis (accession 882899) following incubation at all temperature combinations at 5°C intervals between 15 and 40°C, short temperature was for 6 h and long for 18 h in 24-h cycles, using a thermogradient plate. Results were after 70 d. Germination percentages corrected to take into account estimated viability (n = 30 for each temperature combination).

Pre-treatment

Pre-treating the seeds for 3 months at 60% RH increased germination to 41 ± 29% from 14 ± 10% (P = 0.007; Table 2 and Fig. 4), but the same treatment at 100% RH did not have an effect (P = 0.423). The minimal adequate model only included the treatment, and there was therefore no discernible effect of subspecies.

Macro-climate

Based on our combined germination test results compared with temperature extracted from climate data, we see that the germination temperature requirements are warmer and have a wider diurnal range than estimated from subspecies distributions (Fig. 6). For instance, the temperature of the hotter part of the diurnal cycle from the germination experiments was 35°C; this is close to but warmer than the maximum temperature of the warmest month for all taxa. There were no records at all as high as 35°C, and a few records were close. For diurnal range, no records were as high as the 15°C we observed from the germination test results. Mean diurnal range across taxa distributions was 8 ± 1°C (Fig. 6), and the widest range was 11°C.

Fig. 6. Bioclimatic variables at occurrence locations for M. acuminata taxa extracted from WorldClim 2.0 (Fick and Hijmans, Reference Fick and Hijmans2017). Dashed line represents optimal temperature for the warm part of the diurnal cycle (35°C) from the germination test results; dotted line represents optimal diurnal range (15°C) from the germination test results.

Discussion

Stored M. acuminata seeds had an almost absolute requirement for alternating temperatures. Within a seed accession, there was non-uniform sensitivity to alternating temperatures, such that by pre-treating seeds with a period of constant temperature, higher final germination percentages were achieved than without such a pre-treatment. Seeds had hard coats, but we found that these were permeable to water.

Our results were comparable to many tropical disturbance-adapted species (reviewed by Vázquez-Yanes and Orozco-Segovia, Reference Vázquez-Yanes and Orozco-Segovia1993; Baskin and Baskin, Reference Baskin and Baskin2014). Within the Musaceae, M. acuminata thermal requirements were similar to M. balbisiana (Stotzky et al., Reference Stotzky, Cox and Goos1961; Stotzky and Cox, Reference Stotzky and Cox1962). In these studies, there was also an almost absolute requirement for alternating temperatures, with maximum germination at 35°C for 5 h (mean 59%), and low temperature was 15°C for 19 h (mean 70%). Additionally, low levels of germination of M. balbisiana occurred following short and even singular exposure to alternating temperature, but continuous cycles were required for maximum germination (Stotzky and Cox, Reference Stotzky and Cox1962). As a combination, germination was optimal (80%) at 5 h of 35°C and 19 h of 12°C. The cooler lower temperature requirement for M. balbisiana reflects the subtropical and at times higher elevation distribution of M. balbisiana – East India to Yunnan, China.

At the macro-climate scale, temperature and diurnal ranges were rather similar across subspecies distributions (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. S3). In general, temperatures estimated from the climate model (WorldClim) were cooler than in our germination tests; diurnal range was also smaller than may be optimal for germination. This suggests that micro-climate, rather than solely macro-climate, is important in germination of M. acuminata. This is because soil temperature, when exposed to direct sunlight, may heat considerably more than the air temperature usually used in climate data and modelling. Furthermore, this observation supports our expectations that seeds are adapted to specifically detect gaps in the forest canopy following disturbance.

Specific optimum temperature fluctuations were different between our two experiments: 5.7 ± 3.9°C for the thermogradient plate experiment and 15°C in the other germination tests, suggesting a degree of plasticity in fluctuation requirement. Pearson et al. (Reference Pearson, Burslem, Mullins and Dalling2002) proposed four categories of response to alternating temperature dynamics according to seed mass. Using these same categories, our results place M. acuminata into category three, where there is a positive response to increasing temperature fluctuation in the range of 0–16.7°C, but there is no dramatic optimum or cut-off point. For this group, seed mass was the heaviest category in their sample (20.9 ± 14.2 mg, mean and standard error), M. acuminata seeds were even heavier than this (40.45 ± 6.80 mg).

At the micro-climate scale, soil mean temperature and diurnal fluctuation are dependent on several factors, including topography, canopy, litter, air temperature and solar irradiance (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Kim, Oh and Lee2000; Saatkamp et al., Reference Saatkamp, Affre, Baumberger, Dumas, Gasmi, Gachet and Arene2011; Bilgili et al., Reference Bilgili, Sahin and Sangun2013). Additionally, mean temperature is correlated to distance from the edge as well as the size of the gap (Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Burslem, Mullins and Dalling2002; Saner et al., Reference Saner, Lim, Burla, Ong, Scherer-Lorenzen and Hector2009; Takada et al., Reference Takada, Yamada, Shamsudin and Okuda2015). Temperature fluctuations are also dependent on the burial depth of the seed in the soil (Pearson et al., Reference Pearson, Burslem, Mullins and Dalling2002). Finally, the composition of the forest effects both the mean temperature and range of the diurnal fluctuation, for instance, M. acuminata seeds would be inhibited from germinating in the temperatures of old growth forests, but may occur in oil palm plantations (Hardwick et al., Reference Hardwick, Toumi, Pfeifer, Turner, Nilus and Ewers2015).

Our results show that, after storage, most seeds from the same inflorescence are non-dormant but some seeds are; germination is increased following a period of stratification or after-ripening. Heterogeneity in dormancy could be part of a bet-hedging strategy whereby seeds have variable levels of dormancy to aid dispersal and maximize seedling establishment (Ng, Reference Ng1980; Tielborger et al., Reference Tielborger, Petru and Lampei2012; Gremer et al., Reference Gremer, Kimball and Venable2016).

We found M. acuminata seed coats did not limit imbibition. However, for seeds that have not been dried and frozen, physical dormancy cannot be completely ruled out; especially as drying increases imbibition rates in Musa seeds (Puteh et al., Reference Puteh, Aris, Sinniah, Rahman, Mohamad and Abdullah2011). Furthermore, Musa seeds clearly invest in physical defences, which may correlate with physical dormancy. In other species, alternating temperatures have also demonstrated removal of physical dormancy (De Souza et al., Reference De Souza, Voltolini, Santos and Paulilo2012; Jaganathan et al., Reference Jaganathan, Han, Song, Selvam and Liu2019), and this in relation to disturbance (Jaganathan, Reference Jaganathan2018).

Much of the variation in our results was the result of the variation between accessions. This is despite seeds being treated and collected in the same way. Additionally, the overall viability of our accessions was low, and Musa seeds have been shown to have variable levels of desiccation sensitivity depending on species and maturity at collection (Kallow et al., Reference Kallow, Longin, Fanega Sleziak, Janssens, Vandelook, Dickie, Swennen, Paofa, Carpentier and Panis2020). The loss of viability observed here may also be the result of immature seeds not having fully developed desiccation tolerance (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Hong and Roberts1991; Hay and Probert, Reference Hay and Probert1995; Leprince et al., Reference Leprince, Pellizzaro, Berriri and Buitink2017). Seed maturity within and between bunches can be important for traits such as desiccation tolerance and germination potential. Despite our efforts, it is possible that immature seeds were collected during field expeditions and this may help explain why it is then difficult to obtain consistent results for seed germination. When collecting bananas in the wild, it is difficult to access mature seeds as it is rare to find ripe or mature bunches in the forest, presumably because of predation and frugivory.

M. acuminata seeds demonstrate sensitivity to alternating temperatures for seed germination suitable to detect gaps in forest canopies following disturbance. These results can directly be applied to the management of banana seeds for conservation, and to more easily access material for phenotyping and breeding.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0960258520000471.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute for providing seeds, in particular Anuar Rasyidi, M. N., Ahmad Syahman, M. D., Mohd Shukri, M. A., Suryanti, B. At Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, thanks the Seed Collections team at the Millennium Seed Bank for curating the seeds and carrying out the Tetrazolium Chloride tests; Kirstine Manger and Kay Singleton for assistance with the germination tests; John Adams and Pablo Barreiro for thermogradient plate and incubator set up. At KU, Leuven thanks for Tom Vanderstraeten and Kevin Longin for the embryo rescue. The authors are also grateful to all donors who supported this work through their contributions to the CGIAR Fund (https://www.cgiar.org/funders/) and in particular to the CGIAR Research Program for Roots, Tubers and Bananas (CRP-RTB).

Financial support

This work was funded as a subgrant from the University of Queensland from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation project ‘BBTV mitigation: Community management in Nigeria, and screening wild banana progenitors for resistance’ [OPP1130226]. The Royal Botanic Gardens Kew is part supported by a grant in aid from the UK Department of Environment Food and Rural Affairs.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: S.K., R.D. and J.D.; methodology: S.K., R.D. and J.D.; software: S.K.; validation: S.K., R.D., B.P. and F.V.; formal analysis: S.K.; investigation: S.K. and R.D.; resources: B.P., S.B.J., A.M., R.S., M.B.T. and J.D.; data curation: S.K., R.D. and A.M.; writing original draft: S.K.; writing reviewing and editing: S.K., B.P., S.B.J., F.V., R.S. and J.D.; visualization: S.K.; supervision: B.P., S.B.J., R.S. and J.D.; project administration: J.D.; funding acquisition: B.P., S.B.J., R.S. and J.D.

Conflict of interest

None.