“The field refracts. Only by exposing the specific logic of this refraction can we understand what it is all about, although it is certainly tempting to tie this logic directly to the forces of power in the social world.”

Pierre Bourdieu – Flaubert’s Point of View (emphasis in the original).I. Superiority

Do economists rule the world? Are they “Masters of the Universe” (Stedman-Jones Reference Stedman-Jones2012)? Or are they mere puppets of self-serving politicians and the robber barons that rule the economy? And who or what are they anyways? No doubt, the role of economists in society, their influence on society, and society’s molding of them have been a long-burning issue. From Keynes to the Queen to the small-town mother watching the evening news, basically everyone formulates an opinion about these professionals. And how could they avoid it anyways, given the overwhelming presence of the profession in public life. At least in relation to their social science and humanities colleagues from the academy, they are “superior” in that regard (Fourcade, Ollion, and Algan Reference Fourcade, Ollion and Algan2015) – they usually have more income, do more consulting, and have more discipline-external institutions under their control than any other comparable subject. Indeed, they seem to have uniquely influenced the “new way of the world” (Dardot and Laval Reference Dardot and Laval2014). But the superiority and the attention that comes with it also have their unpleasant aspects, both for those who enjoy it and perhaps even more for those who write about it. For where there are passions that affect everyone, interests often are not far away. It is therefore key to have a critical look at the social scientific work that deals with this subject.

II. Social scientific approaches to the role of economists in society

It is possible to divide the existing social scientificFootnote 1 literature on the role of economists in society into a continuum between two poles – a rather structural, objective pole on the one hand and a rather phenomenological, subjective one on the other.

Authors situated on the objective pole start conceptualizing the role of economists from broader structures that surround them – these are of a differing degree of abstraction and may include whole societal systems of production, as in the case of Robert Heilbroner (Heilbroner Reference Heilbroner1988, Reference Heilbroner and Samuels1990) who links economists” thought directly with the capitalist mode of production that surrounds and sustains them. As a consequence, the ideological, justifying character of academic economics in which the political character of the capitalist system is rendered natural, seems “inescapable and inevitable” (Heilbroner Reference Heilbroner and Samuels1990, 109), as a kind of mental mirror to a specific organization of society. A similar structural-marxist argument seems to be made by Harvey (Reference Harvey2005) who seamlessly blends in academic economists in his narrative of how “capital” managed to push back “labor” in the western world since the 1970's. For Harvey, this development needed “some rationale” (ibid., 54), to be provided, among others, by economists.Footnote 2

Then there are authors who develop the structural view into another direction, namely by introducing sub-systems that tend to deflect and to transform the wider context. These are specifically and historically grown sub-structures such as fields, professions, and the rules and regulations linked to them. This is the case in the work of Marion Fourcade who designates as structures both material and mental practices that are themselves structured in an increasingly complex system she calls “cultural gravity centres” (Fourcade Reference Fourcade2009, 20f.). This makes for a dialectical approach to the study of the relationship of political culture and economic knowledge. Fourcade attempts this for the economists of the USA, Britain and France, linking them to specific national values and intellectual patterns that interact with each other. In that sense, the specifically American individualism, its “competitive egalitarianism” and the weak federal state created an environment which favoured an academic economics that overtakes this individualism and pro-market values but inflects them in a way that still secures its professional autonomy. This can account for distinctive features of American economics, such as its historically early, strictly formalized nature, institutionalized in PhD training (ibid., 32-40): “the modern history of American economics is fundamentally a history about 'rival’ ideals of quantification … rather than rival ideals of economic analysis (as is arguably the case with French economics.)” (ibid., 83f.). These features then “loop back” in a transmuted form to the wider society - in this particular case in the form of the imposition of a highly specialized and selective division of intellectual labor onto the system of higher learning of the United States (ibid., 40). And from there, of course, it has further impact on the economy and politics of the country.

There are further approaches that emphasize structures, but usually at a less global level, which allow for more space for individual initiative and creativity. Analyses such as that of John Campbell (Reference Campbell1998) situate the ideas of economists within the mix of daily political struggle between various factions. But this is conceptualized within a wider context of (rather volatile) cognitive and normative ideas which each have a concrete as well as a more tacit dimension. Politicians and economists of various creeds now try to promote their ideas within this changing context, for which they use specific strategies to exploit specific “public sentiments” or features of the Zeitgeist to which their ideas are more or less adjusted – such as, for example, the relative conceptual simplicity offered by what Campbell calls “supply-side economics” which resonated well with “policy makers” (ibid., 387). Angus Burgin’s account of the development of ideas of the early leading economists of the Mont Pelerin Society (Burgin Reference Burgin2012) focusses on interactions. It aspires to be “a narrative that examines how its central figures developed, explained and justified their beliefs; how they alternatively influenced and opposed one another’s opinions, how they navigated the perilous relationship between politics and philosophy …. It approaches ideas neither as abstractions that unfold in a realm wholly distant from politics nor as more tools that are involved to engender a desired change.” (ibid., 7). Kim Phillips-Fein’s work (Reference Philips-Fein and Mirowski2009) seems to apply a very similar approach, with a slightly different focusing on towards the businessmen that played major roles in the genesis of neoliberal society.

Finally, the body of literature with the most phenomenological thrust is the so-called “performativity” approach. These are those studies in the tradition of the social studies of science, such as that of Callon (Reference Callon1998), Yonay and Breslau (Reference Yonay and Breslau2006), Kessler (Reference Kessler2007) and above all MacKenzie’s work on finance (MacKenzie Reference MacKenzie2008). Here structures of any kind are rather a background noise without a particular pattern or history. What is emphasized, on the other hand, is how seemingly random interactions of various individuals – academic economists and “practicing” economists alike – lead both to the development of economic theories (or “technologies”) as well as their efficacy in everyday economic practice. But this also implies underscoring the muddled, heteronomous character of this very same economic technology: “Technologies can develop in different ways according to circumstances, the design of technical systems can reflect a variety of priorities, and “users” frequently reshape technical systems in important ways. Ultimately, the development and the design of technologies are political matters.” (MacKenzie Reference MacKenzie2008, 26). This view, of course, is rooted in a relativist epistemology of science such as put forward by writers like Barnes (Reference Barnes1983), Bloor ([1976] Reference Bloor1991), Knorr-Cetina (Reference Knorr-Cetina1981) as well as Latour (Latour and Woolgar [1979] Reference Latour and Woolgar1986) and Callon (Reference Callon and Law1986). Especially in the works of the latter three a series of more traditional epistemological dichotomies, such as that between truth and falseness or subject vs object, or persons vs things, are loosened or discarded altogether (see also Fowler Reference Fowler2006, esp.105f.). This means that one should “zoom in” and show how, in specific times, places, and circumstances, people of different walks of life work together to create or to modify technology which then shapes the life and work of these, and other, people in turn. Moreover, implicitly or not, it goes hand in hand with a view of those who are engaged in these interactions with other people or technologies as rational, strategically acting, actors maximising some form of utility. One may again quote MacKenzie who discusses the eventual take-up of modern Finance Theory by US financial analysists during the 1960s and 70s after an initial period of rejection: “The U.S. financial markets are, if nothing else, places of entrepreneurship, and so it is not surprising that some practitioners began to see ways of making money out of finance theory.” (MacKenzie Reference MacKenzie2008, 82). Once picked up, economic technologies develop a life of their own, in the unintended sense of the self-fulfilling prophecy (Merton Reference Merton1948), and in turn constrain the maneuvers of future actors. Hence, we are left with a kind of rather chaotic, ever-changing and “acting” “structure.”

What we have, therefore, in conclusion, are various contributions to the understanding of the role of economics and economists in society. These contributions are spread along the poles of structure vs. agency, of societal vs. individual or “actant” source, of macro- vs. micro-influences. For authors like Heilbroner or Fourcade it is the societal or structural forces that structure economics. For others, like Campbell or Burgin, it is the living and struggling actors that push towards societal change. And for the performativity-representatives it is the instruments of economists, that is, their theories or “technologies” that have a very large influence onto what happens (or does not happen) at societal level. No doubt, each of these aspects – social structures, interactions of actors, and the independent existence of concepts or theories – must play a role in the examination of the relationship of economics/economists with their surrounding society. However, it would be advantageous if these contributions could be combined and accumulated in one perspective – might structure and agency not be linked in such a way as to further the investigation of broader institutions without taking away the “economizing” aspect of individual actions, or the tendency of certain ideas to realize themselves in practice? How do broader structures “trickle down” to perceptions of specific groups anyways? And how does the engagement of these groups in turn (re-)mold the existing structures? This is no doubt a very ambitious endeavor, and not without certain dangers.Footnote 3 Moreover, what also seems to be missing in all these approaches is a distinction between different groups – both in terms of who produces economic thinking and who applies it. In other words: who are the economists spoken of here, and what is their social and educational background? Marion Fourcade herself acknowledges this lacunae when she admits in a footnote in her conclusion that “A more focused analysis would, for instance, trace the complex battles over discursive and scientific style and relate them to the social and intellectual trajectories of particular actors and groups of actors within their own (national) field.” (ibid., 313, emphasis in the original). But it is not simply a different degree of focus that would take different groups and their culture into account, but also a focus of a different kind. For we would have to take into account internalized structures, and how these interact with the wider structures of academic economics and the society.

Hence, one needs a framework which merges the structural approach, the concern of the pre-dating of disciplines, institutions, specific values, with interactions between agents of different social origin and different cultures and, lastly, with a concern for uncovering the economic dimension of all this. The epistemological position asserted by Pierre Bourdieu may be able to provide such a framework.

To be sure, the theoretical and empirical elaboration of this position has been practiced for some time now, both in the broader realms of the sociology of culture (Sulkunen Reference Sulkunen1982, Fowler Reference Fowler1997) and the narrower confines of the sociology of science (see Lebaron Reference Lebaron2001, Kim Reference Kim2009, Münch Reference Münch2014) and education (see Reay, David, and Ball Reference Reay, David and Ball2005). As the reader will see, I am merely expanding the application of this epistemology to an area in which it was, until very recently, not common, that is, to the point of intersection of the sociology of science and the sociology of education.

III. Fields and their consequences

How does field theory attempt to construct a comprehensive sociology that distinguishes between various groups? In Science of Science (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu2006) Bourdieu writes the following about his approach to the sociology of science as opposed to that of others: “One of the central points on which I part company with all the analyses I have discussed is the concept of the field” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu2006, 32). For him

a field may be described as a network, or a configuration, of objective relations between positions. These positions are objectively defined, in their existence and in the determinations they impose upon their occupants, agents or institutions, by their present and potential situation (situs) in the structure of the distribution of species of power (or capital) whose possession commands access to the specific profits that are at stake in the field, as well as by their objective relation to other positions (domination, subordination, homology etc.). (Bourdieu and Wacquant Reference Bourdieu and Wacquant1992, 97)

Agents are thus born and/or socialized into specific worlds in which there are differing forms of capital – first of all, of course, into the “space of social positions” (e.g Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1984[1979], 128f.) that encapsulates the “field of power.” But some of them are also socialized into other fields, with more or less different forms of capital than those prevalent in the field of power – the most relevant for our purposes here is the scientific or academic field (e.g Bourdieu [1984] Reference Bourdieu1988, 50). To each of these positions – whether, for example, a position in social space relatively rich in cultural capital or one relatively rich in economic capital – is attached a specific culture, including concomitant values and attitudes. Overall, this amounts to a life-style -and a practical philosophy (the symbolic realm) which, in its choices and selections, is also, at least implicitly, related to all the other positions of the respective field. In this culture is expressed the specific habitus of an agent. The habitus as a set of dispositions and the “sense of place” of an agent, at the same time permits to modify the acquired culture and limits one’s perspective. This limitation concerns, above all, the objective truth of one’s own field position, in other words, the tendential “purification” of interests and one’s self-exaltation (which is a form of misrecognition, see Bourdieu and Wacquant Reference Bourdieu and Wacquant1992, 51). In the field of science, this purification is known as the “interest in disinterestedness” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1975, 26). Hence, in order to understand any position-taking from a Bourdieusian standpoint, one must link the objective position of an agent in social space, and the concomitant original culture, with the position and concomitant culture aspired to in a specific field like that of science. This, then, is also true if we are to understand position-takings of the same agents outside of the scientific field. The reference point remains the acquired field position and field culture. More specifically, it then seems appropriate to investigate this very transformation of habitus and its dispositions between different fields, which may be called a refraction.Footnote 4 The socialization into a field and its standards of excellence may be called a refraction because, according to Bourdieu, the habitus can only be modified, never remade completely from scratch (see Wacquant Reference Wacquant2014, 6-8). How is one to study this refraction? What values and attitudes exactly are refracted? What kind of habitus do these values and attitudes represent? What are the social structures in which this habitus is minted?

Methodology

I would like to give initial, tentative answers to these questions by way of an empirical exploration rather than by a fully-fledged theoretical exposition.

I will take an interview sample of German economics students as my case in point.Footnote 5 Why students? They are arguably on the threshold to a field, and according to field theory it is there where their original habitus with its original tastes and dispositions is transformed into consecrated expert views, both for the students themselves and for others (Bourdieu and Passeron Reference Bourdieu and Passeron1990[1970], 194-210, Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1996[1989], 36-45). Because of this, one may expect in interviews with students a particularly eminent juxtaposition of contingent opinion and consecrated testimony, of original and changed habitus – in a way it is refraction in action, so to speak. One may witness here the production of a new point of view, at least from the “subjective” perspective. However, as is amply clear from Bourdieu’s own empirical studies on the French educational and academic fields of his time (Bourdieu and Passeron [1970] Reference Bourdieu and Passeron1990, and Bourdieu [1989] Reference Bourdieu1996), there is a rather considerable gap in terms of the objective fit of different students with their subjects. This is especially so in times of educational expansion (Bourdieu and Passeron [1970] Reference Bourdieu and Passeron1990, 222-225). But because even those students who fit less well with their subject experience some form of refraction (which is linked to the acceptance of inequalities, see ibid. 207-209) to their habitus, we might therefore not speak of the concept in the singular, but in the plural, as refractions. I am, however, here interested in the specific habitus — in the refraction of those students that fit with their discipline and its difference to the habitus of those who “don’t fit in.” This raises the question of how to operationalize “fit” with a discipline.

In what follows I will compare two ideal-typically constructed groups of students – the recognized and the non-recognized students. Via the former I mean students who carry objective signs of recognition in the field, such as holding tutorships or research assistantships, having been accepted for a PhD by a German university professor of political economyFootnote 6, or being granted academically competitive studentships.Footnote 7 Recognition thus defined is therefore an empirical indicator for objective fit with a discipline. The point was to separate those who are already recognized by recognized representatives of the academic field from those who are not, to investigate how their views of themselves, the world and their discipline varied, and then to take this as a starting point for further inquiries. This insight into what, in Bourdieusian terms, would be called the disciplinary reproduction of economics (Bourdieu and Passeron [1964] Reference Bourdieu and Passeron1979) will thus, at the same time, give us an insight into the refraction of the habitus involved. As will be known, economics students have already been the subject of social scientific attention (Marwell and Ames Reference Marwell and Ames1981; Rubinstein Reference Rubinstein2006; Frey, Pommerehne, and Gygi Reference Frey, Pommerehne and Gygi1993; Mearman et al. Reference Mearman, Wakeley, Shoib and Webber2011). However, this interest often centers around questions of how “egoistic” or “altruistic” students are made by studying economics, or whether they have already been “egoistic” before. The point here, rather, is to probe for, and to work towards a better understanding of, potential links and connections of “egoism” and “altruism” rather than to unequivocally define and to measure them. It is true that this question is extensively covered via largely quantitative analyses by German sociologists, namely by way of comparing survey data of economics students with students from many other disciplines (see for example Windolf Reference Windolf1992; Georg, Sauer, and Wöhler Reference Georg, Sauer, Wöhler, Kriwy and Gross2009). The approach developed here, however, distinguishes structurally between different groups of students and focuses more on the detailed attitudes and values, rather than to gather them via standardized ways.

The following quotes have been taken from semi-structured interviews of 57 economics students from various stages of their studies – from Bachelor to Master/Diploma to PhD level. The majority of interviews was conducted during the academic year 2015/16 at one medium-sized German university economics institute.Footnote 8 The students were recruited directly (via phoning or emailing them at their institute sites), via snowballing or via recruitment in and around economics students clubs and the lecture halls. They were asked to narrate about their way into the discipline, to state their impressions of their current studies, their plans for the future as well as their political leanings. In a discursive manner (Ullrich Reference Ullrich1999), it was attempted to probe the students to fall back to a practical, more relational thinking (which, of course, a Bourdieusian epistemology assumes and presumes). The point of this was to arrive at a basic understanding of how they perceive their studies and the changes this brings.

IV. Exploring the appropriation of economic thinking

If one compares how recognized students see themselves and their discipline, one may discern a range of differences which seem to pertain to those students that are not recognized. These may be grouped into a) construction of an early contact with economics, hence of a founding myth compatible with a meritocratic ideology, b) a strong identification of economics with specific imaginations of “tangibility” or “practical” approaches, often linked to personal experience, and c) the subsequent spread of the economic logic onto all areas of thinking, towards the “finished” belief, to be applied to reality.

a) Early contact with economics

The recognized students in the interviews tend to construct contact with explicitly economic questions early on in their lives and educational trajectories. A prime example of this is PeterFootnote 9, a Bachelor student and tutor at a rather prestigious foreign university at the time of the interview. His father holds a PhD in economics and his mother is a secondary school teacher. His way into the discipline seems straightforward according to his description. After graduating from the Gymnasium,Footnote 10 he completed a gap year working in the library of a college in an African country, a position his father organised for him. He explains the two factors arousing his interest for economics, at the time:

IFootnote 11: […] so, I mean, in countries like this one [Germany] you are guarded by all these economic things quite well, right? Of course, inflation is discussed everywhere and [raises voice] “oh, oh, oh!” But most people don’t know what inflation is, right?

T: I also don’t know what inflation is. Ok, money devaluation, but-

I: Yeah, well, theoretically maybe, right? And obviously, everything gets more expensive, but, but this isn’t really it. […] I mean in [African country] you have a proper inflation, right? Like around 50 percent per year. That means, or even more, ah? […] Well, I say when we came there and when we left again, a kilogram of rice cost two, three times as much, in that time span, right? This is already something, when you see how much per month your expenses rise, right? Luckily our, our, our money also increased due to the exchange rate devaluation. So it wasn’t that bad. But, this is just what you recognize what you don’t have here [in Europe] not so much, right? Ahm, this was such a thing. I think that this brought me to be interested in it [economics] more. Right? The second was just simply because I sat idle at the library. There was absolutely nothing to do. […] the whole library was full with political economy books. Then sat down one day, picked the micro introduction book from the shelf and read it through, right? Then I took a Macro book, and so on. And then I thought I would be quite cool [to study economics].

Another example would be Philipp, coming from an engineering (father) and nursing (mother) background, who is an economics PhD student at the time of the interview. He draws a connection between his curiosity about cartoon film and his interest in economics:

I: Ahm, and also our monetary system, I have always been fascinated by that, how our monetary system works. […] I have always asked myself, when I was five years old, I asked questions to my father how this can work with the monetary system. And why everybody wants to have money, and then I firstly learned that the equivalent value only gives money its actual value, ultimately. And there was also an episode of Duck Tales [a cartoon series produced from the late 1980’s to the early 1990’s], that’s no joke, I was really young back then. There is an episode, I recently watched it again […] there is a remote village in which there is no money, and then Dagobert Duck introduces bottle caps there. And then the prices rise, and everybody complains that the prices are that high. And then he supplies an airplane which distributes new bottle caps every day. And then I thought, as a small boy, of course, now all people are richer because they have more bottle caps now, but suddenly the prices rose even more, and then the food in the menu cost ten times as much and then the penny dropped for me that there are deeper relationships than a fixed price relationship, and that I have always found interesting.

Jan, son of two engineers and himself an economics PhD student, also signifies his early interest in the subject by remembering how he checked an introductory economics text-book after he finished his Abitur.Footnote 12 Mats, another PhD student whose parents are teachers of informatics and mathematics, respectively, links his selection of political economy with his father’s interests:

I: I think history simply, the word itself, these are stories, everybody likes stories, and for me this, 'tis very exciting to see these large relationships, history above all offers that. History offers the large relationships, political economy tries to explain the large relationships, in a different dimension, where this large whole that was, ahm, always interesting to understand, why things are what they are […]. Ahm, I can’t [explain more fully where this interest comes from]. It was just there. Certainly also comes from my father, because … he always has been interested in politics and history. We have the whole basement filled with history books.

What appears to happen there is that the interest for economics is anchored in specific experiences or facts in the past that seem, to the interviewees, to be rather mundane (an internship in a library, watching cartoons, a basement filled with books). This may include events of a bigger scale as well, so that some recognized students also name the Iraq war of 2003 or the financial crisis of 2007ff. as reasons to study economics. But always an early interest of economics is attached on to these events, which may serve as some form of foundation narrative, both to the narrator and to his or her listeners. Because of the link to everyday occurrences, this myth attains somewhat of a meritocratic character – after all, we are all exposed to inflation, we all have access to cartoons, to libraries. But not all of us successfully veer into academic economics because of that, which subtly implies that there is some unexplainable ability (i.e. “talent”) that must be responsible for “seeing” an interest in some mundane fact and that shows itself rather earlyFootnote 13 (Bourdieu and Passeron Reference Bourdieu and Passeron1979[1964], 14f.). We will see in section b) that this can be tied analytically with specific and rather vague conceptions of what constitutes a legitimate way of argument and what not.

Now, compare this with the flippant, indifferent remarks of a non-recognized student, Max. He is an economics Master student with medium-level civil servant parents. He describes how he selected the subject during his final days at secondary school:

I: […] Yeah, I also have [studied with] a mate [in the Gymnasium, the German grammar school] that also studied in [X], he was there half a year before me. And then, well, we have been friends for a bloody long time, so said to ourselves, “let’s study together!” Then we checked what was there. And then I became aware of the degree, I already had political economy in mind anyway, and then this was clear for me. I then didn’t apply elsewhere [at other universities/for other degrees], but did this directly. […] Like, “well, political economy, ok, bang, we do that now”. […] I mean for me this was simply a continuation of school. “I do three more years of studying political economy.” That is why I, yeah, as I said, I didn’t make a plan […].

Stefanie, another non-recognized Bachelor student whose father is a physician and mother an optician, is almost brutally open about her way into economics. Instead of constructing a foundation narrative, like the recognized students do, she says that it was a quasi-rational decision following from her mathematics abilities and recommendations by her family and teacher to pursue the subject. She concludes:

I: - You can do something with it. And I found it just to be the most logical thing, simply, this, this is, simply. You can do so much with it, I mean, you can build up so many different directions and top it up with something. Master, whatever, simply when you are doing internships.

Perhaps the most interesting conclusion emerging from this short comparison is the degree to which “naked” rationality (in the sense of purposive rationality) plays a role in the constructions made. This is the case most for those students who are least recognized and least for those who are most recognized. The latter supplement their narratives of study selection with unexplainable and early indicators of interest which subtly refer to talent and merit. This fits very well with the notion of disinterestedness proposed by a Bourdieusian sociology of science. But it is a very distinct version of interest in disinterestedness, as we will see in the next section.

b) A taste for the “tangible” and the “practical”

The recognized students of the sample tend, much more than the non-recognized ones, to distinguish different academic disciplines. They tend to assess economics – as against other social sciences and humanities – as having the quality of being “clear”, “precise”, “tangible” or “not fuzzy”. Very often this is justified by reference to economics’ mathematical modelling. Tom, a young PhD student with a father that works as an IT system administrator and a medium-level civil servant mother, elaborates on his own experience:

I: […] I mean what I like about this model theoretical [stuff] that I do is…. You have, you have a model. And you have clear assumptions, right? I have to formulate which assumptions I take. How do I define the utility function? Yes, what are, what are the central elements? Better put, what are the central assumptions that produce my statements, ahm, at the end, right? I mean, I do not produce the statements of the model, but I simply put assumptions into it, and out of that comes an answer to a question that I put, right? […] And the important thing is, you have formulated clear and succinct assumptions at the beginning, right? And these can be criticized […] You simply have clear points of attack and clear definitions, you can discuss very clearly with them, right? And if you compare this with many social scientific things, there it is often the case that you, that you discuss, you can discuss the whole evening and somehow it does not progress, or you still haven’t understood the other person, because you haven’t put down these assumptions this specifically, right? And it is similar with mathematical models, right? I mean, with mathematical models it is simply clear. Right? I can look at it, I know it is right or wrong. At least on the mathematical level, and then I can clearly discuss it. And that, I find, is often much harder and fuzzier with legal or social scientific questions, and I am also not that good on that terrain, in my view. Can’t do it, there are other people that can do that splendidly, I can’t do that. An’ I see my strengths rather in this theoretically rooted discussing of questions. […] That has always been what interested me strongly, I mean mathematical questions, right? And it’s simply like, math is a very clear language, and that is nice for me, and I find it good, ah, to work with it, right? This, perhaps this, pushed me more and more towards this political economy direction, rather than towards a social scientific direction, and the questions business administration is answering.

What can be clearly seen from this excerpt is how his critique of epistemology of other, less “formalized” Social Sciences is linked to his abilities, and, eventually taste and, indeed values of clarity, tangibility and the like - or better, what he understands to be these values. These values seem also at play in Ben – a second-year Bachelor student and tutor whose parents worked as secondary school language teachers. During his Gymnasium time he wrote for the school newspaper, doing an internship at a local newspaper in addition. He recollects:

I: But I have somehow, I mean, I always found it quite good if one somehow had a fixed topic. For one part, I have written a lot in this section on current school events [of the school newspaper] because there was a concrete starting point. Ahm, I was rarely some-, actually not at all, somebody who brilliantly [elaborates] one’s own thoughts in the sense of “I simply want to tell somehow something what comes to my mind.” We also had a couple of people [at the newspaper] who then blethered on a lot. And, ahm, I also had an internship with [regional newspaper] and, they also wanted that I simply, somehow just like, I mean [names youth section of that newspaper] […] They have a youth, ah, youth section.

T: Ok.

I: And there some people somehow write what has just happened, and what their feelings are. And there I thought, “Hey guys, this is not my thing. I do not here have to sell myself, but I would like to write about something relevant.”

T: Hmh.

I: And, ahm, maybe this political aspect was a little bit of an exception, but there you had starting points which you could just discuss.

T: Hmh. Hmh.

I: I still remember this self-publicizing I always found very, very tedious.

In other words, he connects his selection and interest of economics to personal experiences with other kinds of reasoning. His reasoning is de facto relational. He defines economics for himself by what, in his view, it is not (Bourdieu and Wacquant Reference Bourdieu and Wacquant1992, 127-31). This clear distinction of different styles of reasoning, even though not a distinction of disciplines, can be said to be used in an analogous way to distinguish academic disciplines as they were described by Tom. There is also the linkage, once again, to mundane and personal experiences. This cannot be found with the non-recognized students. There sharp distinctions between economics as one’s “profession” and the “private” tend to be drawn. Claudia, for example, a young Bachelor economics student with an accountant father and minor manager mother, prefers the business administration over the political economy parts of her education. She states:

I: I find it quite hard to think extremely big [in terms of national economies]. The company is much smaller. This is something that you think about as a private person. You don’t think how you increase the gross domestic product.

Non-recognized students tend to describe their studies as “puzzles” that need solving, but to which they have a certain inner distance. This is presumably due to the lack of inner connection to their discipline and the alienation that follows from it, which forces them to “beautify” their studies, as Stefanie puts it. One may take from this comparison the thorough intertwining of what economists usually call “positive” arguments and “normative” feelings or tastes – but only for those students who fit well with the discipline.Footnote 14 This difference of distance spills over to the last area we are looking at, the broader world view.

c) The spread of the economic logic

Recognized students tend to be so much invested in economics and its particular epistemology and tools that it is barely surprising that this world-view starts to exert an influence on topics that are not immediately economic by definition. In short, the economic way of thinking seems to become incarnated. It becomes a sort of reflex in which the personal and the official tend to merge. This can be seen with Jan and how he retrospectively describes his selection of discipline. He starts by noting that he “of course” “weighed [the alternatives]” when it came to his study choice. Then he lists his criteria of selection (interest, economic prospects and security), before going on to criticize the “fuzzy” information policy of the university. He finally arrives at a rather “rationalized” account of his selection:

I: […] I mean I knew that I am interested in the humanities, well, social sciences.

T: Hmh.

I: That is, questions that deal with society, with, with people in society. Therefore also like political science, sociology, psychology was also in it, [these] were things that also interested me.

T: Hmh.

I: On the other hand, I always very much liked math in school. Aahm, I also was quite good in it, and I liked to apply mathematics. I knew that the natural sciences interested me, but that I didn’t want to do this that intensively for several years, physics, bio[logy], chemistry. I could eliminate that for myself, could also eliminate informatics. I could eliminate languages, literature, things like that. Even if it was interesting, it somehow wasn’t really my thing, I mean somehow social sciences really was the thing where I knew this is what really interests me. Exactly, there political economy was a social science. I mean, I see it as a social science, a Gesellschaftswissenschaft [social science]. Then I borrowed a book from the city library, an introductory book, some book, and read it in the tram to see what it really concretely means [to study economics], what you do there.

Ah, this I found interesting, some things I didn’t understand, but the questions I found exciting and I also liked the relatively clear style of reasoning of political economy. This I liked. Well, and, ahm, I was aware that if I, for example, study political economy, I have better professional chances overall as compared to studying philosophy. Yes, indeed, if you look at it on average, that’s simply the way it is.

Notice the technical notion used to describe his study selection (“eliminate”) and, again, the reference to “exact” or “tangible” information. One finds here a specific form of rationality and individualism which has become incorporated into the habitus, so that it can produce statements that express these virtues ad hoc. Other recognized students like Simon, Master student with an engineer father and a secondary school teacher mother, refer to “understanding incentives” when it comes to describe their study selection. And Jan wraps it up when he renders, in typical economics textbook fashion, his own study selection as something “normative” which indeed cannot be inquired into in “positive” terms:

I: But in the end it is just a preference, right? One person somehow doesn’t like chocolate, the other one [likes] dark chocolate.”

Here one can see already the rather sharp divide of “normative” vs. “positive” statements that can be found in virtually any mainstream economics textbook and which is so distinctive for the whole profession. One may see this as the result of what Bourdieu calls pedagogic work, “[…] a process of inculcation which must last long enough to produce a durable training, i.e. a habitus, the product of the internalization of the principles of a cultural arbitrary capable of perpetuating itself after [pedagogic action] has ceased and thereby of perpetuating in practices the principles of the internalized arbitrary.” (Bourdieu and Passeron Reference Bourdieu and Passeron1990[1970], 31). Interests are rendered contingent and non-intelligible. Furthermore, “scientific” knowledge is closely associated with “clear” and “precise”, that is, mathematical and modelling, data. Hence Mats, when asked to comment on the benefits of a minimum wage for the economy, remarks that it is “[d]ifficult, I mean, it is of course, “tis not my field of study.”Footnote 15 The same goes for Theo, recognized economics Master student with an engineer father and a teacher mother, who professes that “[…] if I am not so much into the topic […] I’m always cautious to formulate a strong opinion about it.”

It could thus be theorized that earlier experiences with what are perceived as “fuzzy” or “nebulous” or “vague” approaches or persons are transformed within the context of academic economics and under the guide of a specific habitus (which would need to be specified later on) into a sharp distinction between scientific versus non-scientific thought, picking up for this the specific notions that can be found in many economics textbooks, such as “rational”, “efficient” “maximise” or “preference”, which all have a specific meaning that, however, tends to disappear behind the objectifying and justifying aura that surrounds these notions within the field of academic economics. It is a sort of ethical scientific norm that, in its specific way, follows Wittgenstein’s maxim: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” (Wittgenstein Reference Wittgenstein1995[1922], 85). But that logic, on the other hand, also implies that, once the “leap into science” has been made with the help of exact, causal thinking and mathematical modelling, and once evidence has been secured through these procedures, positive truth may be uttered with all the more certainty and self-confidence. Whereof one can speak, thereof one must proclaim. And with the help of model-building, the recognised students and soon-to-be economists are able to speak about a whole lot of things in a convinced and (at least for some) convincing way.

Hence Jan is, with the help of his education, able to position himself against the concept of a minimum wage:

I: Minimum wage, I do have a clear position there. Have to think what I say now […] I am against the minimum wage. Not because I find its goal bad but because I believe, well, believing is not 100% security, that it cannot reach the goal in the best possible way. The goal is to get more people into earning incomes, higher incomes. And I think one can attain these goals by other measures, where you don’t have the danger that there are somehow dislocations on the labour market. That means that there might be fewer jobs. That is not that clear because the studies are so different, but given that, there is this danger that the minimum wage leads to less jobs. Why don’t you do it differently, by redistributing more or having a negative income tax a la Friedman, which has no direct effect on the job market. And, the minimum wage doesn’t help at all those who do not have a job, those who are the poorest, those who do not have incomes. […] you can achieve the goal [of helping the poor] differently than harming the companies. Because this can lead to lack of demand for work by the companies.

Whatever the exact positioning within the panoply of established positions within economics is (there are of course also ways to argue, with the discipline-specific tools at hand, for the minimum wage), what seems clear is that at the bottom of it is a conviction that the chosen path is right, legitimate, true, and that it serves a higher, altruistic purpose (to increase the welfare of people). If this conviction is not there, as in Max’s case, the whole positioning within economics seems rather absurd, because, despite his studies, he “cannot see the difference” between various economic theories, such as Keynesian or Neoclassical ones. Indeed, as Bourdieu states, for those not invested in the game the field-specific struggles seem pointless and rather ridiculous (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1988, 778-780). Hence Max again refers to the fact that he doesn’t “have a great vision.” Instead, like other non-recognized students, he sees his studies “as a puzzle” to be solved but then left to itself after the job is done. Consequently, his view on something like the minimum wage has the character of a “naked opinion”. He refers to the hardships some migrant workers face in Germany and asserts, as a sort of rather “imprecise” rule of thumb, that “you don’t hurt the economy much with 8,50 Euro [minimum wage per hour in Germany at the time of the interview].”

This concludes my exploration of economics student’s narratives of their disciplinary experiences.

Now, how can this be fed back to a more theoretical level?

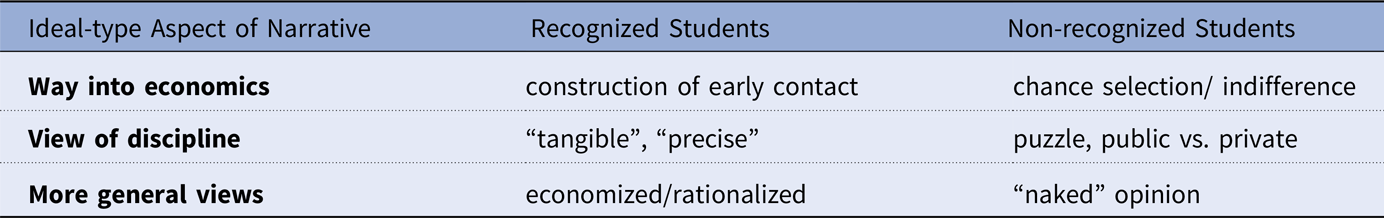

V. Towards an economics of externalism

With the help of the summary above (Table 1), I come back to the questions posed earlier. First: What values and attitudes exactly are refracted? The comparison of recognized and non-recognized students points towards a preference of the former for a specific and rather narrow form of arguing that prefers unambiguity of definition and mathematical formalization over other forms of expression or communication (like essays, “free” discussion, or artistic devices). This is linked to repeated and frustrated contact with other groups or types of knowledge that are perceived as “fuzzy” or “not tangible” enough. There is also a clear tendency to objectify, rather brutally, those styles of thought as “self-publicizing” or even “blathering.” Opposed to this is the part of the narrative of the recognized that concerns their own thinking. It constructs an innocent adoption of interest in economics in early mundane experiences that subtly and rather mystically alludes to “talent.” Finally, the adopted instruments and tools of economics – the concepts of utility maximizing actors, of rationality, of causal models, of mechanisms and determinations and so on – take up room beyond their usual applications, and so perhaps can be said to round out the construction of an identity of “economist” that fits well with the structural position in which the recognized students exist and subsist. It is here where we might see the construction of what Bourdieu calls the “interest in disinterestedness”, the interest in the field-specific ideals of excellence. Contrary to this narrative, the non-recognized students tend not to see such a sharp distinction between different styles of thinking or reasoning, but rather between their studies of economics vs. their private preferences. This can be interpreted as a distinction of “public” vs. “private” realms. Understanding their studies as a kind of proto-job, they perceive its tasks as “puzzles” or as something which they must “beautify”, which bears witness to their inner distance to their subject. Consequently, there is no construction of “talent” via early exposure to economics and also no “contagion” of “non-economic” areas or topics with economic logic. Indeed, seemingly paradoxically, if there is cynicism or pure material considerations, it is by those who are less adapted to the field (i.e. the non-recognized), not by those who are better adapted.

Table 1. Summary of empirical results of types of students in various aspects of their narratives

This, then, leads to the next question: What does this all mean? What kind of habitus and structural roots does the expressed belief-system of the recognized students represent? The recognized economics students, as defined in this paper, seem, if compared to non-recognized students, to originate largely from what might be called a technical-educational background – their parents worked or work mostly as engineers, natural scientists or secondary school teachers. These students are also overwhelmingly male, and furthermore have graduated with very good marks from their secondary school education. This resonates with the available (and rather scarce) statistical evidence of the social origin of academic economists in Germany (see for instance Möller Reference Möller2015, Graf Reference Graf2015). It also raises fresh questions about how to proceed further, empirically and theoretically, within the Bourdieusian framework. One could argue that it is this specific technical-educational background that serves as a proper cultural capital to enable an easy refraction of habitus towards that of an academic economist. But to prove that one would need further empirical validation, since one would need to show that groups with a different socio-demographic background – say, for instance, a humanities professor’s daughter with an excellent secondary school graduation – are less likely to excel in economics, nor to choose it. This presumes a rather detailed, comparative and sufficiently large sample of what has been called “recognized” students of various disciplines, which would have to be complemented by “subjective” views of other subjects as it has been sketched out here.

Lastly, if it would indeed be possible to prove such a refraction that is situated within and between the social and the academic fields and their specific, mutually complementing, “fitting” and recognized students, what are the consequences of this for the study of economics and its role in broader society? A few questions suggest themselves: first, how does one make sense of the evident willingness and forcefulness of academic economists to offer their expertise on markets (fields) alien to them? It seems that this question might be answered out of the logic of the refracted economic habitus and its place in the academic field. In other words, what, in their refracted habitus, makes economists to be “haunted by state thinking,” to be seemingly “dependent on responding politically to political demands, while at the same time defending [themselves] against any charge of political involvement by the ostentatiously lofty character of [their] formal, and preferably mathematical, constructions” (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu2005, 10)? In this version, an investigation into the socialization of recognized economics students may contribute fruitfully to an explanation of what might be called “the external drive” or the economics of externality, understood in a broader, rather Polanyian, sense of the word (Polanyi [1944] Reference Polanyi2001). It is at this point that further empirical research in a Bourdieusian epistemological vein might complement the existing literature on the “economics of economists”, performed mainly by the performativity theorists and others discussed earlier in this paper - in the sense that it allows us to hopefully piece together a more complete and coherent picture of how economists, from family socialization to academic research to consulting practice in the market place, come to think and do what they think and do.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the following persons for helpful comments and advice on earlier versions of this paper: Bridget Fowler, Andrew Smith, Sebastian Thieme, Anders Hylmö, as well as the editors of this issue and the anonymous referees. The writing of this article was supported by an ESRC PhD scholarship, ESRC ref. no ES/J500136/1.

Tim Winzler is a post-doctoral researcher who currently works as a tutor at the University of Glasgow. He recently finished his PhD on the study selection of German economics students and is currently preparing further publications on this topic. He specializes in the sociology of knowledge and science as well as the sociology of culture, in particular its Bourdieusian applications.