Introduction

In 1479, a widow appeared at the manor of the lord of Herzele. She delivered the chainmail of her late husband as payment for the lord’s right to ‘meilleur cattel’: the house’s best heirloom.Footnote 1 Of the 14 subjects owing this death duty that given year, she was one of three households making the trip to the residence of the local potentate. This act of compliance probably helped procuring a renewal of her lease of one of the seigneurie’s major holdings.Footnote 2 Not all residents were as docile to turn in significant portions of their inheritance. Another entry in the seigneurial accounts describes how the bailiff collected the meilleur cattel from Joes Boudins’ late wife, but only after winning a trial before the city court of Ghent’s aldermen of the ‘Keure’.Footnote 3 Boudin had fought the lord’s claim to one of his cows, by appealing to his status as ‘outburgher’. Acquiring citizenship from nearby towns or cities, while generally (even exclusively) residing outside of that town’s jurisdiction, was called outburghership (these people became bourgeois forains, buitenpoorters, Pfählburger).Footnote 4 One of the main advantages of such status was the exemption from certain seigneurial rights, such as meilleur cattel. Boudin’s subscription was probably not yet fully ratified, since his registration as citizen of Ghent only dated from 21 October 1477, and his wife passed away before the prescribed admission period of one year and one day. Several years later, Boudin was more successful in escaping the lord’s justice: When loose cattle of Boudin and his brother damaged properties throughout Herzele, he enjoyed protection from further prosecution, whereas his sibling was banished for one year.Footnote 5

The events in Herzele were typical for the power play in the county of Flanders between the 13th and 16th centuries. Outburgership was an edifice of the tension between four socioeconomic players: lords, country dwellers, cities, and the count. The political influence of cities and the count disrupted the authority of local lordships over their subjects. A request from 1409 by eminent lords from the castellany of Aalst sketches the situation perfectly: this remarkable group of lay and clerical lords resorted to a joint complaint before the Flemish ‘Audiëntie’ (the comital council preceding the later Council of Flanders).Footnote 6 In their request, they wailed about how the city and bailiff of Aalst enrolled outburghers in an unlawful manner in order to ‘under the guise of citizenship [i.e. outburghership], in several ways to diminish our lordships and the profits they entail’.Footnote 7 An enumeration of no less than 23 articles described the so-called infractions upon their lordships. Most contestations had to do with seigneurial taxes and justice claims such as fines and death duties as meilleur cattel. The bailiff of Aalst protected his outburghers fiercely, both by physically threatening seigneurial officers and by suing them in court of law.Footnote 8

The relative success of Flemish outburghership is closely tied to the power struggle over influence and surplus extraction in the countryside. It aligns with studies focussing on the interaction between urban and rural spaces.Footnote 9 Citizen status not only tied rural residents to urban communities but also provided protection against aggression and extortion by lords. Overzealous seigneurial violence and fiscality targeted against rural subjects was counterbalanced by omnipresent strong towns, who had the political and military might to defy most isolated lords and their private militias. This resulted into power struggles between the thirteenth and 16th century. The gradual rise of a central state apparatus from the late middle ages onward slowly settled most judicial conflicts between authorities in town and countryside. Despite a concomitant rise in central fiscality and a relative decline in socioeconomic power of the cities however, outburghership pertained certain fiscal and judicial perks in the county. The resulting power equilibrium between cities, lords, subjects, and count would endure until the French revolutionary army invaded Flanders in 1795. In other words, the ‘pervasiveness of lords’ was undermined by the accessibility of urban privileges to peasantries.Footnote 10

Sandro Carocci coined the term ‘pervasiveness’ in order to measure how (un)successful lords were in extracting surplus, labour, and obedience from their subjects. Absentee owners of big, powerful estates did not necessarily control their residents more effectively than lesser nobles inhabiting a local domain. The problem of his notion of ‘pervasiveness’ is however that it remains quite broad and vague. One of the best and most concise definitions is the following: ‘the degree to which lordship intruded, and was capable of, shaping ‘land and people’ under its control’.Footnote 11 To what degree this so-called ‘pervasiveness’ can be measured through a workable paradigm and method of inquiry remains unresolved. It is however a worthy endeavour, as Wickham stated in 2021, to study (supra)local socioeconomic power relations in order to better understand how communities worked, be it states, cities, or local lordships.Footnote 12

A possible way to assess the pervasiveness of seigneurial surplus extraction and seigneurial justice is by weighing it against the effectiveness of contestant powers. In Flanders, the most accessible ally for rural residents against the dominating lordship was a nearby city. Garnot discerns four different forms by which villagers in ancien regime France resolved conflicts. According to the available options, severity, costs, possible rewards, or risks that accompanied disagreements, French subjects chose their strategic conflict-resolving moves cautiously. Apart from litigation (‘justice’), people could resort to three other forms of negotiation. ‘Infrajustice’ concerned transgressions or litigation enabled by existing rules and procedures, but which was at some point withheld from the judicial apparatus. The most obvious example was lawsuits that were used to leverage opponents into negotiating a compromise, after which the ongoing procedures and charges were dropped. Then, there was ‘parajustice’: forms of conflict settlement which had become illegal, but often survived through certain ‘rules’ of common practice. Duels and other acts of vengeance fall within this category. Lastly, ‘extrajustice’ comprised involuntary toleration of violations. In other words, all parties disapproved the misdeeds in question, but pursuit of retribution was either not possible and/or worth the trouble. The conflict thus remained unresolved.Footnote 13 Outburghership fits within the categories of both normal ‘justice’, as well as ‘infrajustice’, when its modalities and privileges were stretched and interpreted too freely in relation to seigneurial claims. Citizenship was a way for rural residents to counter the pervasiveness of their lord with the pervasiveness of urban authorities. This was by no means a straightforward process, and from the 13th century onward, it resulted in contentious power struggles.

The subject of this paper is by no means new. Outburghership as bone of contention between Flemish lords, cities, and counts has received its due attention. The historiography however largely neglected one quintessential perspective, namely that of the country dweller. Most historians primordially covered urban history and the power struggle between Flemish cities and the count.Footnote 14 Within that narrative, authors implicitly assume that country dwellers eagerly acquired citizen status as a means of tax evasion and legal protection. This paper pursues the scope towards peasant agency, and how outburghership fitted within their toolkit of resistance forms against lordship. In other words, the perspective is reversed towards that of the dominated subject: In how far did country dwellers succeed to employ citizen status to hinder the pervasiveness of their lords? And how effective, accessible, and common was outburghership? The first section discusses how and why external citizenship appeared in Flanders and became so exceptionally successful between the 13th and 16th centuries. Consequently, the importance of outburghership for rural residents will be assessed, weighed against other means of contesting the seigneurie.

Outburghership in Flanders

External citizenship was a phenomenon from the north of contemporary France, Switzerland, and Germany to the Southern Low Countries.Footnote 15 Within this restricted area, Flanders was the uncontested focal point. Nowhere else was the absolute number and concentration of outburghers as high as in the Flemish county. Although powerful cities such as Ghent and Courtrai registered thousands of rural citizens, the urbanities in the Northern Low Countries counted some hundred at best.Footnote 16 Nor did the institution of external citizenship survive until 1795 in other places as it did in this densest urbanized region north of the Alps. It was precisely this unique landscape, densely dotted with smaller and bigger cities, acting as counterbalance to princely and seigneurial power, that ensured the exceptional endurance of citizenship for country dwellers.Footnote 17

Each Flemish lordship was inevitably unique. Such seigneuries were ‘a property right which entailed the exertion of public power over its inhabitants’.Footnote 18 Most power claims considered here however were common enough in Flanders and premodern Europe. Flanders adds a relevant contribution to the current state of the art, since the county displays several similarities as well as differences from the more intensively studied countryside of primarily France and England. Given its feudal bond with France, Flanders shared similar feudal and seigneurial bonds and obligations with its French counterparts. The vast historiography on the English feudal economy has shown that events on the continent often rhymed with those on the island, as was the case with revolts.Footnote 19 Flanders was dotted with seigneuries; however, our grasp of how such lordships functioned on a daily basis (i.e. how pervasive lords were over their subjects) is disappointingly shallow. The count of Flanders used external citizenship as an indirect attack on local lordship. Registered country dwellers could formally resort to urban courts, thus bypassing their lords’ bench of aldermen.Footnote 20 Specific analyses on how outburghership was used to break up seigneurial lordship, especially from the perspective of peasants, remain quite rare.Footnote 21

The paradoxical problem with outburghership is that despite a considerable amount of dedicated studies, much remains unknown about its precise purview. This lacuna is caused by the nature of historical research by both urban and rural historians, who either focussed on limited case studies (both in time and space: often one city and its immediate hinterland across one or two centuries) or grand narratives scratching the surface.Footnote 22 We possess many decent publications on particular cities and their specific privileges from the first half of the 20th century onwards (e.g. Huys, De Brouwer and later Monballyu, Castelain and others).Footnote 23 Verbeemen attempted an all-encompassing study on outburghership in 1954, providing an unprecedented overview of external citizenship and its impact on the old regime Low Countries. Verbeemen’s work however mostly focused on comparing and explaining the general trends in the numbers of external citizens, rather than investigating how these institutions worked in practice.Footnote 24 Similar critiques can be formulated for an overview from Maddens from 1986, whose primary intent was to facilitate further research.Footnote 25 That same Maddens excelled also in historiographical case studies, primarily focused on Courtrai. Other noteworthy studies from the 1970s onward advanced our knowledge on Flemish outburghership greatly in terms of how urban status protected rural residents, and how lords and urban authorities fought over jurisdictions.Footnote 26 Another scholarly trend has been to investigate specific cities and their influence on the surrounding countryside, along with demographic and socioeconomic effects.Footnote 27 Other great studies rightfully placed outburghership in between the political power struggle of the Flemish count, cities, and lords. Frontrunner of this socioeconomic and political analysis was Thoen (inspired by similar trends discerned by Van Uytven for Brabant), followed by scholars such as Scheelings, De Rock.Footnote 28 These latter studies already pointed their lens on how rural communities could instrumentalize urban privileges for their own agenda. The agency of country dwellers however often quickly reverts to the background of such narratives. The following section remedies these shortcomings by scrutinizing the general set of advantages citizenship provided for the Flemish peasantry from the 13th century until its demise in 1795, with specific attention to how seigneurial subjects tried to escape taxation and jurisdiction.

Rise, decline, and geographic density of outburghership

The exact origin and genesis of external citizenship is obscure, but enough is known to situate and contextualize it adequately.Footnote 29 After the inception of communal and urban rights (around the 11th, 12th century), normally restricted to members living inside the urban jurisdiction, the preconditions required for ‘poorters’ or ‘burgers’ became more flexible. Well-travelled citizens (merchants for example) and/or persons who had no (permanent) residence inside the city’s jurisdiction, but wanted to enjoy its benefits, inspired a pragmatic status.Footnote 30 The precise origin of outburghership, be it outgoing and returning merchants, wealthy citizens with landholdings in the countryside, growing of urban agglomerations towards larger outskirts, is unclear and variable depending on the studied cities and sources. The same goes for how exactly the respective city acquired or rather appropriated its citizen rights.Footnote 31 The exact modalities for becoming an outburgher knew as many iterations as there were respective cities. Generally, citizens were asked to reside in the city for minimal periods of time throughout the year, to pay urban subscriptions and/or taxes. Additionally, birth within the city’s jurisdiction or descent from (external) citizens could provide children with urban privileges.Footnote 32

Why bother with citizenship as a rural resident in the first place? The most obvious incentive resembles the pull factor of urban communities: namely a certain judicial and juridical independence from lordly power. Urban courts often promised more professional and favourable proceedings than the aldermen of local lordships.Footnote 33 More notorious was extortion by violent, corrupt bailiffs or lords (as push factor). A known misuse among lawmen was the so-called practice of ‘composition’ (‘compositie’). Normally, the procedure was intended to swiftly punish perpetrators of minor offences. Rather than being trialled before the lords’ bench of aldermen, and putting up with all its costs and hassles, the bailiff could propose the perpetrator a reasonable settlement. The offender thus ‘enjoyed’ a discounted fine along with his reprimand. Some bailiffs however abused composition to force unreasonably high fines upon (sometimes innocent) subjects, who then paid disproportionate ‘discounted’ fines under threat of violence or the uncertain outlook of a sketchy trial.Footnote 34 If one considers the often minimal cost of a few sols parisis (s. par.) per subscription or per year for outburghership in comparison to the maximum fine applicable in the lowest possible seigneurial jurisdiction (three pounds (lb.) par.), citizenship was a relatively cheap luxury.Footnote 35 A skilled thatcher in the seigneurie of Avelgem had to work for around ten days mid-16th century to earn three lb. par. His unskilled pupil earned half as much, which still made citizenship arguably accessible.Footnote 36

Another well-known advantage of outburghership was the exemption of certain seigneurial dues. The most important lordly taxes evaded by citizenship were the despised inheritance levies such as ‘mortemain’ and ‘meilleur cattel’. Initially, mortemain was a death tax weighing on serfs. As unfree workers bound to the land, the lord could take all their possessions after their death. Originally a measure to counter flight of serfs, the Commercial Revolution rapidly changed medieval socioeconomic relations in the Flemish countryside. Serfdom virtually disappeared by the end of the 13th century, and dues such as mortemain were softened. A lot of lords started demanding ‘meilleur cattel’ instead of mortemain. This was a boiled-down version of the former right, whereby peasants had to give up their ‘best piece’: often furniture such as beds or cattle.Footnote 37 Poorer subjects could only give up kettles or even rags.Footnote 38 The relatively high impact of these taxes, combined with their macabre timing (the death of a relative), made these inheritance dues among the most infamous and hated in the county.Footnote 39 Citizenship offered an attractive immunity from said taxes, since those under urban jurisdiction were exempt from mortemain and meilleur cattel. This is why during the late middle ages, the amount of outburghers increased dramatically.Footnote 40

The heyday of outburghership and urban power undoubtedly was the late middle ages. The cities could claim most power at the end of the fourteenth and beginning of the 15th century. The power of the Flanders Members (the three most prominent regional capitals Ypres, Ghent, and Bruges, along with the largest rural entity: the Franc of Bruges, had far-reaching political and fiscal leverage) was great. Comital institutions could hardly keep up with the administration and judicial and political quarrels accompanying the increasing amount of contested power claims. Between 1500 and 1600 however, the proverbial dust would settle. This contrasts with the preserved source material on external citizens. Most of our knowledge about Flemish outburghership before 1550 stems from estimates mentioned in narrative sources, charters, or researched case files. With the exception of Ghent and Oudenaarde, we possess no uninterrupted series of registration for outburghership predating 1500 for Flanders, though some cities have lists for isolated years (see Table 1 below).Footnote 41 Theoretically, every town was obliged to register new citizens (both internal as external) in dedicated ledgers, the so-called ‘poortersboeken’ (or in case of outburghers: ‘buitenpoortersboeken’, though both types could be noted in the same list, which sometimes hampers distinguishment between the two).Footnote 42 As can be seen from Graph 1 and as will be argued below, this discrepancy in the source material coincides with the initiated decline of urban political power, as well as a decreasing need for outburghership in the countryside after 1550.

Table 1. Preserved outburgher lists for prominent cities in Flanders and Brabant with considerable numbers of outburghers. For references, see endnote 36

Graph 1. Averages of registered outburgher subscriptions per city per year, outliers outbalanced by 10-year averages.

From the 13th century onwards, most large towns in Flanders upheld some form of external citizenship. Table 1 shows early iterations of outburgher lists. Undoubtedly, some sources did not survive the test of time. On the other hand, the administration was often deliberately neglected, since it allowed cities and their outburghers more leeway to interpret their privileges more broadly and claim the status more freely. This was primarily to the detriment of lords, who could hardly verify whether peasants claiming outburgher privileges did actually possess such a status. Erik Thoen saw the late 13th century as a decisive turning point, where the strong economic and juridical power of Flemish lords was permanently diminished. This had two important causes: first an ineffective domain management by lords themselves, who preferred fixed (i.e. depreciating) rents over leasehold. Second was the count’s policy to restrict seigneurial lordship by stimulating outburghership.Footnote 43 As Thoen is certainly right in discerning the origins of outburghership and its role in the 13th century, data on the popularity of external citizenship, as well as the persistence of conflicts between lords and country dwellers, suggest that outburghership remained a desirable tool for seigneurial subjects until at least 1550. Although seigneurial power was definitely long past its peak by 1300, rural residents happily continued subscribing for citizenships. This phenomenon can hardly be fully explained by the traditional paradigms on lordship or the emphasis on the triangle relationship between count, cities and lords. This is why the perspective of subject agency is so important. Living and dying without outburgher status meant more loss of surplus to the lord. While surplus extraction in the forms of seigneurial rents, inheritance rights (meilleur cattel), and labour (corvees) were less burdening than before 1300, poorer peasants remained vulnerable to such dues until 1795. An overall rising trend in central taxation between the 16th and 18th century, predominantly exacted upon land users (not necessarily proprietors), sustained the need of rural smallholders and farmers for certain statutory tax exemptions.Footnote 44 This was especially true for an inheritance tax such as meilleur cattel, potentially seizing needed livestock or tools during an ill-timed period.Footnote 45 This fiscal reason, along with surviving seigneurial claims on juridical matters such as criminal justice, explains why outburghership persisted throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, as can be seen on Graph 1 below.

Graph 1 is a reconstruction of yearly subscriptions, based on numbers from published research. As said, we generally only possess coherent series after 1550. This is partly caused by deliberate administrative neglect (e.g. Ghent, explained below), which enabled both seigneurial subjects as city administrators to stretch their claims to privileges and exemptions to the maximum. Undoubtedly, some extant archives were lost throughout calamities.Footnote 46 In order to reconstruct comparable trends and numbers for several cities from circa 1430 until 1795, data were selected on average subscriptions for 10-year intervals. This method was chosen to smooth out exceptional fluctuations and enable comparison between multiple cities. By consequence, certain data were excluded from this visualization (Courtrai e.g. has published numbers for the 16th and 17th century as well, but in absolute numbers, not subscriptions).Footnote 47 Data for Courtrai in the 15th century, Grammont and Aalst were used from Verbeemen (albeit with some cross-referencing and processing).Footnote 48 Numbers for Ghent are published by Decavele, together with an edition of poorterboeken by the city archive.Footnote 49 Decavele used relatively liberal estimation methods to calculate a number of 14.392 subscriptions between 1477 and 1492. Since these calculations are based on the only registers we have for outburghers – which since 1487 only recorded new subscriptions, thus ignoring existing memberships – the estimate is quite sketchy. Given Ghent’s great influence on its surrounding countryside however, and the fierce comital reactions against the cities privileges concerning external citizens, assuming Ghent had several thousands of outburghers, up to and around 15.000 is actually quite plausible (16th century Courtrai boasted a good 12.000 in total numbers according to Maddens).Footnote 50 The Franc of Bruges has left the most lenient source material for this research, published in Schouteet.Footnote 51

The definitive turning point, marking the decline of outburghership subscriptions, is 1550, paradoxically the date where decent series on external citizenship start to appear. This date however coincides with several breaking points marking the downturn of outburghership. First, the ascription of juridical authorities and competences between seigneurial courts, city courts, and courts of appeal became more stable, leading to fewer conflicts and more legal certainty. Although historians such as Thoen and Verbeemen rightly discern the second half of the 16th century as the turnaround for outburghership and city power, the case can be made for seigneurial rights as well. Though Thoen may be right in situating an already crippled nobility from the second half of the 14th century, lords definitely did not stop trying to exert their power and claim their surplus. And while lords complained about how their rights were violated and damaged by cities and their outburghers, they kept collecting rights, appealing against claimed outburghership exemptions and sending complaints to the count.Footnote 52 During the middle of the 16th century however, three important developments occurred, slowly shifting the power balance in favour of central institutions: The absolute peak of Flemish urban powers had passed, symbolized by Charles V’s victory over Ghent’s Rebellion (see below). The Council of Flanders established itself further as a legitimate court of appeal, and its sentences became more respected by lower jurisdictions such as cities and lordships (a trend with roots in the late 15th century).Footnote 53 Lastly, and tied to this former point: the judicial competence of lordships was delineated. Outburghership remained an effective protection against seigneurial justice and dues, but lords pertained competence on criminal justice.Footnote 54

An important rupture mark for the broken power of Flemish cities was the Revolt of Ghent of 1539–1540. This uprising was arguably the last particularist Flemish urban defiance against a centralizing state. While several troubles happened thereafter (among which religious conflicts, and a short-lived republic of Ghent), historians do consider 1540 as a watershed for premodern state power in Flanders. Particularistic city uprisings were no longer a match against imperialistic princes.Footnote 55 Charles V already hinted his centralizing ambitions at the expense of city powers with his joyous entry in 1515. Ghent’s tax refusal of 1537 and its demand for more autonomy in appointing its own aldermen in 1539 led to a relatively short-lived conflict that was easily won by the Prince’s forces. The most important consequence of their defeat was the definitive curtailment of a series of urban privileges, named the Concessio Carolina. While this charter was not unique in Charles repertoire of centralization both in Flanders and abroad, it was the harshest within the county at the time, especially concerning outburghership. Ghent lost its right to uphold external citizens altogether.Footnote 56 Charles imposed several eponymous concessions on Flemish towns, such as Courtrai and Oudenaarde. The main aim there was not to abolish external citizenship as in Ghent’s case, but to enforce a stricter administration, primarily to facilitate central taxation.Footnote 57 This shows in the preserved source material visualized in Table 1 and Graph 1. 1540 marked the turning point in Flanders where both seigneurial and urban power were definitively curtailed and incorporated within a centralized state apparatus that allowed both city and countryside a certain degree of autonomy. Lordships and civic privileges survived as mutual check and balance for each other, but within a Habsburg straitjacket.

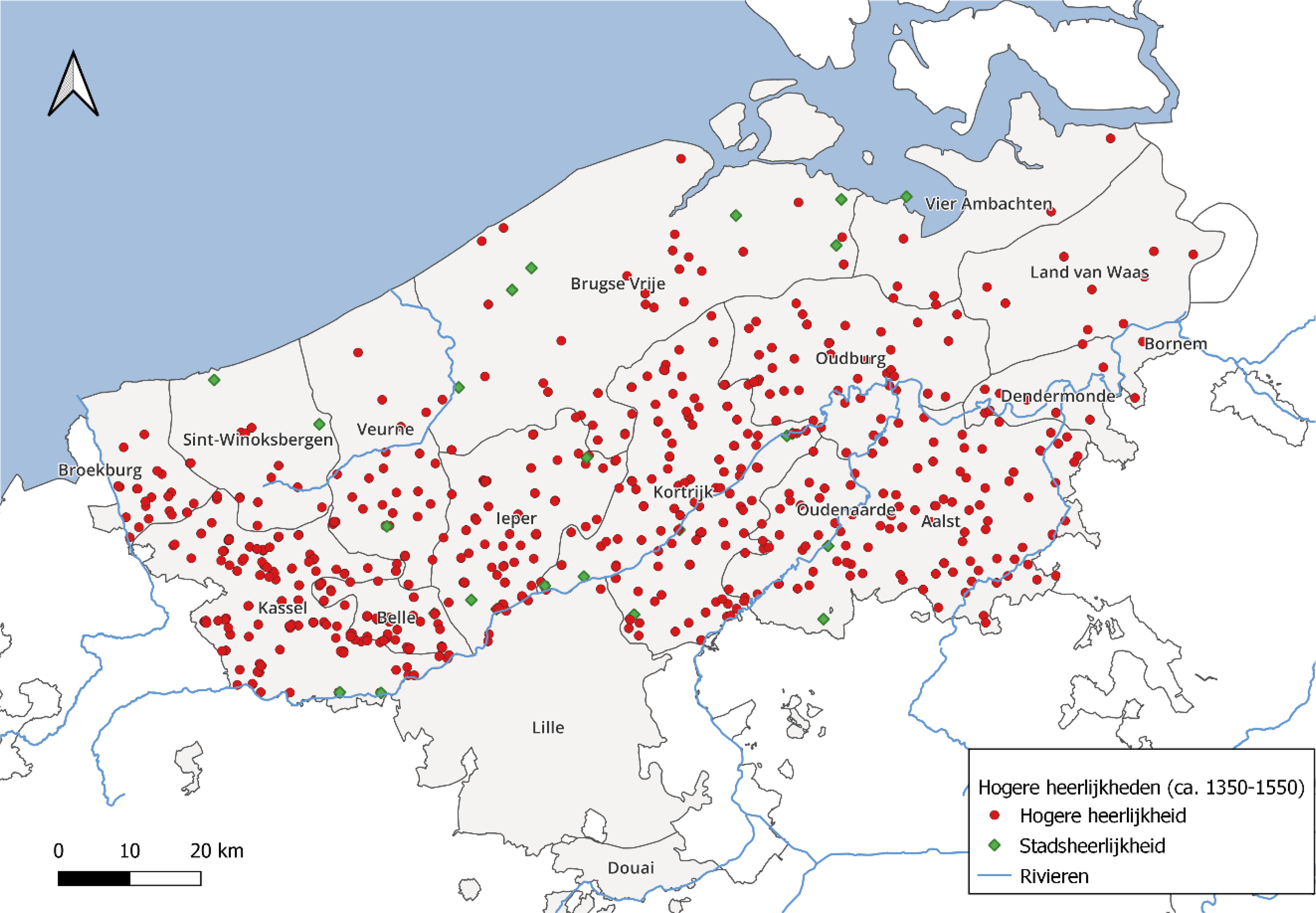

How outburghership freedoms acted as protection against seigneurial arbitrariness is also apparent from other sources. External citizen rights existed throughout the county of Flanders, but not in equal concentration. In those regions where lordships were omnipresent, outburghership subscriptions spiked and vice versa. Research from Adriaens and Buylaert mapped the concentration of lordships throughout the county of Flanders (see Map 1). Their findings are that the majority of seigneuries were present in Inland Flanders, especially in the castellanies of Kortrijk, Ghent, and Aalst. This also coincides with the property and exploitation systems that differed within Flanders. Coastal Flanders was characterized by large landholdings, where a lot of landless labourers farmed the land. Inland Flanders knew many small landowners, subjected to seigneurial rents and other forms of surplus extraction, such as meilleur cattel and chores.Footnote 58 It is precisely in those castellanies where most seigneuries and most seigneurial subjects resided, that outburghership thrived. This also shows in the subscription numbers (see Graph 1) and the sources on conflict between lords and outburghers. The impact on Ghent after 1540 was arguably the greatest, including outburghership, which was abolished by the Concessio. Though even during the 16th century Ghent would pragmatically and clandestinely restart accepting citizenship from country dwellers.Footnote 59 Ghent’s peak of more than 15.000 outburghers during the 15th century however was never to return, as is illustrated by Graph 1 above.Footnote 60 That said, external citizenship would remain popular within the county until 1795. Especially that region with the highest concentration of (high) lordships, Inland Flanders, where outburghership provided the most attractive incentives and advantages (more potential lords who could claim exactions and jurisdictional authority), remains overrepresented in the number of outburghership subscriptions. While cities in Coastal Flanders (e.g. Bruges) never counted as much external citizens, and saw a steeper decline of subscriptions during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, cities such as Courtrai and Grammont upheld their popularity. Courtrai retained between 10.000 and 13.000 outburghers between 1529 and 1580, and even during the longstanding misery of the 17th century, it still upheld thousands of external citizens until 1782.Footnote 61

Map 1. Lordships with high jurisdiction in the County of Flanders. Courtesy of: Mathijs Speecke, Miet Adriaens, Jesse Hollestelle, Pieter Donche, and Frederik Buylaert. Repertorium van de Hogere Heerlijkheden van het Graafschap Vlaanderen (c. 1360–c. 1570) (Ghent, 2023), p. 28.

Though power tensions and jurisdictional skirmishes kept lords, cities, and citizens occupied throughout later centuries, the great antagonisms seen between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries were at an end.Footnote 62 Peasants kept enjoying outburghership as a shield against seigneurial arbitrariness and fiscality, while lords safeguarded their most prestigious (albeit often least profitable) rights of justice. Cities pertained some political and judicial influence on their hinterland through outburghership and enjoyed important fiscal advantages through subscription fees and taxation on external citizens. The financial revenue from outburgher subscriptions for cities remained negligible however. Three quarters or more of urban income came from consumption taxes (excises, accijnzen, and ongelden).Footnote 63 Grammont’s estimated income from 4621 subscription fees for 1396 amounted to 1600 lb. par. (133 lb. gr.), which could pay for 104.000 L of wheat (the yearly consumption of 292 inhabitants).Footnote 64 The prince also profited from outburgher subscriptions, since some cities – such as Courtrai – had to share their subscription fees with the state’s coffers.Footnote 65

Contestation in practice: Outburgership in the defiant subject’s toolkit

To delve deeper into what advantages citizen status provided for country dwellers, this subsection looks into the two most important juridical advantages: judicial protection and fiscal protection. Physical protection was non-existent, unless we confuse retribution for security. If a local militia or lord wanted to hurt somebody, burgher status or not, fight or flight were the only viable options.Footnote 66 While violent confrontations often embellish historiographical accounts, they were relatively rare. More often than not, legal and jurisdictional disagreements were fought out via litigation (by use of justice and infrajustice). In this respect, urban and comital bailiffs eagerly defended their claims of power over outburghers in lordships of the surrounding countryside. Lords not only experienced this as a direct affront to their local authority. They felt it in their purses as well, which is why the aforementioned remarkable group of lay and clerical lords resorted to a joint complaint before the Flemish ‘Audiëntie’. In their request, they complained about how the city and bailiff of Aalst enrolled outburghers in an unlawful manner in order to ‘under the guise of citizenship, in several ways to diminish our lordships and the profits they entail’.Footnote 67 Unless the personal concerns of the sovereign himself or a member of his close retinue were at stake however, lords could barely depend on the count.

While outburghership certainly provided judicial protection and exemption from taxes, that protection was not absolute, especially during politically turbulent times. That said, it often was far better than nothing. And while every century saw enumerate contestations of external citizen rights, the evidence proving outburghership was an effective strategy for legal and fiscal protection is equally abundant.Footnote 68 Violent conflict whereby lords imposed their surplus extraction, such as successful collection of meilleur cattels often were – as Marc Bloch put famously – rare flashes in the pan.Footnote 69 But how effective was this urban protection in practice and how frequently was it used by farmers and peasants, compared to other strategies of defiance and resistance? The following part of this paper aims to put all possible strategies into perspective. First and foremost, not all country dwellers were outburghers. Some studies have tried to put a percentage on the ratio of citizens among the population within Flemish lordships. The results seem to endorse the image of geographic density of lordships and outburghership: namely higher concentrations of outburghers where there were more lords and surplus extraction rights. However, the situation on the ground could vary significantly, according to the influence and power of the lord and/or nearby city. Dombrecht reconstructed numbers for seven different districts (ambachten) in the Franc of Bruges, based on tax lists. Between three and thirty percent of the population there were outburghers between 1483 and 1486. This minority can be ascribed to the low density of lordships within that castellany, and the liberty the Franc itself provided to all its inhabitants: everyone was exempt of meilleur cattel.Footnote 70 D’Hoop, in contrast, assessed a majority of inhabitants in the castellany of Courtrai were outburghers, with an average of 70% during the second half of the 15th century.Footnote 71 Reconstructing such numbers is a difficult and nuanced affair. Van der Hoeven calculated outburgher numbers for Herzele, a lordship in the castellany of Aalst. He counted a mere 15% of outburghers, whereas one would expect much higher numbers, comparable to the situation around Courtrai.Footnote 72 Van der Hoeven however only consulted the outburgher lists for Ghent, whereas most of Herzele’s peasants chose citizenship from nearby towns Grammont and Aalst.Footnote 73 Overall, a main indicator for high concentration of outburghers is clearly the presence of a lordship with rights to meilleur cattel. The lord of Herzele successfully collected meilleur cattel from outburghers and won several appeals against outburghers of Ghent, Grammont and Aalst before the Council of Flanders between 1511 and 1536. Only after 1563 the tables turned in favour of the outburghers.Footnote 74 These case studies show that outburghership was not a do-all, fix-all solution, nor an omnipresent status for every subject all of the time. According to the specific lordship and present city power and the power balance at the moment, outburghership was a more or less viable strategy.

Nevertheless, country dwellers happily kept registering themselves before urban administrations.Footnote 75 As said, the main incentives remained judicial and fiscal, although the gamut of possible evasions generally narrowed from the 16th century onward (see below). Arguably, the largest fiscal benefitFootnote 76 was exemption of the seigneurial rights mortemain and meilleur cattel.Footnote 77 Many extant sources illustrate the fervour with which cities successfully defended the exemption of their outburghers from meilleur cattel. While urban status never guaranteed full immunity of death dues – especially from overachieving local lords or their bailiffs – thus leading to judicial conflict every now and then, the dust largely settled after circa 1550. In the case that a seigneurial bailiff claimed meilleur cattel from an outburgher, it was upon the relatives to point the official to their special status. Should the official persevere nonetheless – which they often did, putting local lordship and the threat over urban jurisdiction – the subjects then had to resort to urban officials. After recount of the outburgher’s heirs, the city officials then resorted to mediation with the respective lordship or started litigation to assert the urban exemption rights. Depending on the resolve of the contesting parties, either a swift settlement or a long judicial procedure was the outcome. Both cities and lords with deep pockets and big egos could be entangled in long, expensive lawsuits over petty rights. Lawyer and procedural costs could staggeringly surpass the profitability of seigneurial privileges, which sometimes carried more symbolic than economic value.Footnote 78 To lords and cities, it often was an issue of prestige and power display, rather than financial gain. To peasants however, it meant cheap judicial defence and a chance at keeping their best cow, tool, or bed. And even if chances were small, why not try?

Parallel to immunity for seigneurial exactions, rural residents also tried to leverage their outburgher status to escape more centralized taxation. The prince’s aides were exacted on the countryside through the castellanies, which organized regional and local quotations to collect the owed sums. These taxes were known in Flanders as the ‘pointingen’ (the actual part destined for the prince) and the ‘zettingen’ (the administration costs for the castellany).Footnote 79 Cities negotiated their part in the aides separately with the central authority and could generally achieve moderated contributions. As residents (and farmers) of the countryside, outburghers theoretically fell under the local tax administration, namely that of the castellany. Referring to their urban citizenship, outburghers claimed exemption from the pointingen and zettingen. Their reasoning was that, as citizens, they should contribute along with their city, not their location(s) of residence or of professional activity. In practice however, outburghers barely pulled their weight in urban taxation either, since most of a city’s fiscal revenue (also used to pay the Prince’s aides) was brought up by consumption taxes. Many outburghers rarely visited their city of subscription, thus evading urban dues as well.Footnote 80 The most aggrieved party of these tax evasion practices was the castellany. From the 15th century onward, castellany accounts are rife with procedure costs of court cases against outburghers claiming tax exemptions. De Rock found that over one-third of the castellany of Courtrai’s meetings and local visits were dedicated to outburgher disputes.Footnote 81 The many fiscal exemptions, along with particularistic interest conflicts between cities, castellanies, countryside localities, peasants, and outburghers, fed centuries long of tax evasion and tax disputes.Footnote 82 Reforms between 1515 and 1518 and between 1540 and 1550 settled important fiscal ambiguities, thus trying to reconcile the tense tax rivalries between towns and countryside. After 1540, most outburghers had to contribute with their localities in the countryside.Footnote 83 This only left protection against meilleur cattel as prime advantage of outburghership after roughly the middle of the 16th century, which might explain the relative decline of overall outburghership subscriptions shown in Graph 1.

Coincidentally with the clean-up of fiscal loopholes, centralizing state building efforts from the 16th century onwards increased the overall tax pressure significantly throughout the county of Flanders. Most financial reforms were to the detriment of the countryside and its inhabitants. Although the overall power and influence of particularist cities had decreased relative to that during the middle ages, the cooperation and consent of the Flanders Members remained essential for aid-seeking princes until the end of the 18th century.Footnote 84 Nevertheless, several tax reforms would appear and arguably burden country dwellers the most from circa 1543 onward. Direct as well as indirect taxation forms gradually took larger shares from rural budgets relative to other surplus extractors. Thoen and Soens calculated an increase in average central tax burdens for inland Flanders from roughly 5-8 per cent of the gross output per ha in 1630–1650, to 10–15 per cent between 1650 and 1700, 15–20 per cent in the 18th century.Footnote 85 Together with an increasing state taxation, the potential benefits bound to outburghership decreased alongside with the seigneurial share of rural surplus production. Van Isterdael’s data show similar results on central fiscal pressure in the castellany of Aalst during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Seigneurial rents only constituted one to two per cent of the gross output.Footnote 86 However, outburghership remained a method of escaping meilleur cattel, which explains why outburghership subscriptions steadily declined but coincidentally survived as welcome immunity for seigneurial claims to the inheritance of cattle, clothes, tools, and furniture.

In resemblance to the opportunism of their lords, some outburghers displayed a tendency to stretch the exemptions that their civic membership provided. By appealing to their status as citizens of Ghent, peasants from Kalken claimed to be free of all labour services (corvées, karweien). Their lord brought the case before Ghent’s city court in 1431 and was confirmed in his right to the corvées, outburghers or no.Footnote 87 Similar attempts at dodging labour service, as well as milling rights (molage, vrije maalderij; the obligation to mill one’s grain at the lords’ mill, against taxation), can be found for Eksaarde between 1438 and 1440. It is quite telling that this case also was closed in favour of the lord, in a sentence of Ghent’s city court against their own outburghers. Other cases for Flemish cities prove that while outburghership was certainly a power play of cities in undermining seigneurial power, local peasantries were equally creative and opportunistic in employing the institute of outburgher status in their own interest. The rural population did not merely undergo the struggle for power between lords, cities, and count, but possessed and used agency to try and escape local surplus extraction. City and count supported unruly peasantries when it served their purposes, but did not refrain from acknowledging seigneurial prerogatives from local lords if it suited a peculiar alliance. A telling example of the fickle judgement of urban courts is the case of Merlin Van Der Bauwede from 1559. Merlin took an inheritance piece from his late sister’s inheritance, against the prerogatives of Avelgem’s seigneurial bailiff, who fined Van Der Bauwede the maximum penalty of 60 lb. parisis. Merlin took the case to the court of Oudenaarde. The city’s aldermen ruled against their outburghers’s interest, in favour of the lord of Avelgem. Apart from the lords of Avelgem and Eine however, Oudenaarde fiercely defended her outburghers, until the 18th century.Footnote 88

Briefly after the watershed of 1540, the lords of Avelgem seem to have succeeded in forging a long-lasting relationship of understanding with the nearby city of Oudenaarde, settling years of preceding judicial conflict. A revealing iteration of how the contentious 14th to 16th century power struggles between lords and cities degraded from 1540 onward is the case of meilleur cattel collections at Avelgem. In seigneurial accounts before 1500, one finds notations of the occasional inheritance tax by the local receiver.Footnote 89 The bailiff’s account for 1547–’48 however mentions no revenue for said rights. On the contrary: the seigneurial officer was occupied with a lawsuit between the lordship and the city of Oudenaarde. The account mentions costs for this lawsuit, concerning meilleur cattel (‘angaende den beste hoofden’).Footnote 90 The outcome of the litigation (in the form of a judgement, if one ever fell) is unknown. However, indirect information from Avelgem’s seigneurial bookkeeping suggests a favourable outcome for Oudenaarde’s outburghers. The receiver’s expenses mention payments to the city clerk for excerpts from the citizen lists. There are no other means wherefore a lord required knowledge on registered citizenships, other than discerning who were outburghers – and thus exempt from meilleur cattel – and who were not. Another account from Avelgem’s receiver from 1776 posits it undeniably clear: ’Item payé au griffier de la ville d’Audenarde, pour les extraits de ceux qui ont payé leurs franchise de trois sols par an, pour etre exemptes du milieur chatel’.Footnote 91 Instead of diving in head first and starting potentially expensive and long-dragging litigation, lords and their receivers had become more prudent and pragmatic.Footnote 92 The case of Merlin Van Der Bauwede, along with another sentence from the year 1559, suggests that briefly after the lawsuit of the 1540s, the lord of Avelgem and the city of Oudenaarde settled their differences. A line from the latter sentence reads (about the lordships of Avelgem and Eine): ‘these are the two lordships who do not complain [about our outburghers and their exemption to meilleur cattel]’.Footnote 93

Strategies for contesting the Flemish seigneurie

The study above proves that outburghership was a limited strategy of protection against seigneurial power and surplus extraction, one that moreover was not available to all peasants. With three per cent at worst, and over seventy per cent at best of the rural population possessing civic privileges, this still left a rough minimum of a third of subjects vulnerable for seigneurial claims on their time and/or produce. This begs the question what agency non-outburghers possessed, and how frequent and effective this repertoire of resistance was. Evidently, the source material often stems from the archives belonging to the lords themselves (or religious or governmental institutions) but previous studies have displayed convincing methods to reconstruct the agency of subjects to some degree.Footnote 94 The same principles apply to this study. Seigneurial archives were drafted primarily to facilitate surplus extraction and the exertion of seigneurial power and justice upon its subjects. In so doing, these documents often recorded the exact actions of those peasants to avoid, escape, or withhold given exactions. If we read them against the grain, these sources do not only show us how lords wanted and expected their subjects to behave. They also reveal how those subjects tried to dodge the often oppressing dues and rules of the seigneurie. Perhaps most obvious are fines, intended to punish transgressions (and fill the purse of local rulers). Additionally, more indirect sources or methodologies are charters and regulations declaring measures to remedy past conflicts or misuses, annotations in seigneurial accounts describing tax evasions or unpaid rents, disappearing rights such as labour services.Footnote 95

The following sections delve deeper into the range of strategies country dwellers could use in Flanders between roughly 1400 and 1795, to escape seigneurial power and fiscality other than outburghership. First, lawsuits did happen, though it is hard to determine the frequency with which subjects in the countryside defied lordship by open judicial action. Second, informal negotiation forms, both amicable as antagonistic, between lords and their subjects are preserved in a wide range of sources. Third and lastly, the range of resistance forms outside of the law are considered. Hereby peasants knew all too well that they were acting clandestinely, but proceeded nonetheless.

Lawsuits between subjects and lords

In addition to the confined legal and fiscal protection provided by citizenship, country dwellers had other means of defence within the bounds of justice. Most obvious are lawsuits based on other legal stipulations, jurisdictions, or precedents outside of outburghership.Footnote 96 Both legal and socioeconomic historians have undertaken research into the accessibility and use of courts by both higher and lower strata of old regime societies in the Low Countries. The results and methods of said research are however often limited in space, time, and thoroughness.Footnote 97 Other publications (of which local studies are a prime example) explore specific cases quite thoroughly.Footnote 98 Sources such as case files, but also seigneurial accounts, offer detailed insights into the power struggle between lords and subjects, albeit tentative without quantitative inquiry.

The inhabitants of a seigneurie could and did resort to justice when they perceived that a lord or his officers failed the common good (in essence: the peasants’ interests) within that given lordship.Footnote 99 This is precisely what happened in Ingelmunster around 1653. There, the community’s cash box suffered a deficit of 6000 lb. gr. Jan De Laere – one of the largest local landholders (and outburgher of Courtrai) – started a community-supported lawsuit against the lordship’s officials. In their view, the seigneurial clerk, bailiff, mayor, and aldermen were guilty of ‘bad government’ (‘quaede regheeringe’). A big contributor to the locality’s debt pile were the lord’s fiscal exemptions, which even led some villagers to claim that he should contribute more in the castellany’s taxes.Footnote 100 When it dawned upon Ingelmunster’s lord, Dauphin de Plotho, that he might very well lose the trial at hand, he tried to appoint opponent De Laere as his new mayor. De Laere feared this office would make him complicit of the exact maladministration he was trying to amend, so he declined the mayorship. Consequently, the lord sued his stubborn subject for lèse-majesté. This started a whole new series of legal proceedings, whereby neither party budged an inch.Footnote 101 It should be noted that Jan De Laere, resolved as he may have been, was no simpleton. He possessed one of Ingelmunster’s largest farmsteads and acted as bailiff for another lordship (Waelbrugge). De Laere was in other words a figure who knew the tricks and dodges of local lordship and governmental administration. Moreover, he was an outburgher of Courtrai and sought refuge in Ghent during the conflict with his lord. Nevertheless, the village community of Ingelmunster repeatedly rallied behind and supported him: both by testifying in court, as by financially contributing in procedure costs for the ongoing lawsuits. Elaborate examples of communities taking initiative to litigate against the seigneurie in Flanders are quite rare in the existing historiography. Most publications focus on source material where it is the other way around. The case of De Laere may be exceptional, but it shows how prominent villagers made optimal use of their own agency (money, connections, citizen rights, judicial knowledge) to successfully resist power claims from their lords.

Seigneurial accounts complement the historiographical view on the pervasiveness of local lordship. As administrative bookkeeping tools, they reveal additional aspects of seigneurial logic, other than lawsuits or denombrements traditionally do. By comparing the (expected) yield of seigneurial rights to the duration and cost of litigation, enforcement and administration accompanying said rights, we can evaluate if the collected money was worth the trouble. If the economic value of certain forms of surplus extraction was heavily surpassed by the cost of their application, we should re-evaluate the meaning of lordship and its pervasiveness to lords. A case file about fishing rights in the river Mandel shows that contestation of seigneurial surplus extraction was not always primarily a matter of pure economic profit but also an issue of symbolic capital. The lord of Ingelmunster and the abbot of Ename (the abbey owned the lordship of ten Dale adjacent to Ingelmunster’s lands) disputed about fishing rights in the Mandel. The fishing rights in question were unprofitable, but the judicial procedure took almost two decades, surpassing any sum the fishing rights could render.Footnote 102 Regardless of their nature, even the most prestigious forms of capital could become priceless or untenable. This befell the lord of Avelgem in the 17th century. Accounts for this lordship show suspended entries for the inheritance right called ‘dubbele doodkoop’ from 1602 onward.Footnote 103 The aldermen bench of Otegem, a parish under the jurisdiction of the lord of Avelgem, had struck a verdict against their lord. The sentence denied Otegem’s seigneur any further payments of dubbele doodkoop. The lord had appealed the case before the Council of Flanders, where the sentence was ratified. Subsequently, the case was pursued at the Great Council at Malines. There, the procedure dragged on for decades. A sentence is unknown, but if the appeal at Malines was ever settled, it was presumably in favour of the Otegem community. While payments of ‘doodkoop’ reappeared in later 17th and 18th century accounts of Avelgem, it was always under parishes other than Otegem, where the entry was left blank.Footnote 104 This case proves that it was possible for rural communities to fight seigneurial claims in court (up to the highest level) and successfully defy lordship and its surplus extraction claims.

Pragmatic negotiation forms

Lawsuits, let alone violent incidents, were vastly outnumbered by smaller, pettier frictions. People could of course resort to violence and litigation, but this was primordially a last resort. Why unnecessarily anger community members and neighbours, start expensive litigation, or risk physical injury, when a heartfelt discussion with some (feigned) kind words could resolve a problem far easier, cheaper, and safer?Footnote 105 This daily commonplace reality has left fewer traces in archival records than exceptional transgressions.Footnote 106 Nevertheless, many disagreements proved too big for involved parties to amend by mere informal discussion and negotiation, and too small or expensive to persevere through a full-fledged lawsuit. Such situations resulted in iterations of what Garnot calls ‘infrajustice’: disputes whereby one of the involved parties resorted to means of justice (starting a judicial procedure), without the case ever concluding before a court. To a certain extent, infrajustice can be regarded as some sort of hybrid form of judicial action. People resolved their problems with one foot inside the legal framework and another foot on the outside. Quite unsurprising, different stakeholders regularly acted along the lines of the permissible and/or the possible. Sure enough, conflicts involving outburghers and meilleur cattel delivered their fair share of practices of infrajustice. Seigneurial bailiffs collecting inheritance rights during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries proved pragmatic at best and corrupt at worst.Footnote 107 Sometimes they (rightfully or not) refused to believe peasants claiming urban status, seizing the household’s best piece either way. When the external citizens resorted to their city’s officials, who in turn delivered notification (or if they were overzealous, served him a summons), the meilleur cattel was reluctantly returned.

The nature of these forms of infrajustice sometimes poses methodological issues: the paper trail can come to a sudden halt. This is commonly interpreted by historians as marking a struck agreement outside of the court, though faulty record-keeping or administration remains a possibility. This is illustrated by a peculiar case of meilleur cattel in the Franc of Bruges – where all inhabitants were exempt from the inheritance right since 1232 – when the lord of Praet had confiscated a horse of Anthonis, son of Riquarts. The lord exacted this illicit claim, arguing Anthonis’ deceased mother was a former subject of his lordship. Meilleur cattel was however due to the lord of the place of death. Anthonis asked and received support from the Franc’s aldermen, who adjourned all court meetings throughout the Franc until the horse was returned from 2 December 1424 until 28 December that same year. From there, no further traces concerning the outcome of the case exist, so presumably the lord of Praet conceded and Anthonis received his horse.Footnote 108

Through formal and informal discussion, claims of power and possession could be debated (partly) outside of official courts. The dread for costs and difficulties of yet another lawsuit lead some lords and communities to look for other pragmatic solutions, rather than enduring iteration after iteration of an endless judicial war of attrition. Such battle-weary agreements were struck for the much disputed meilleur cattel rights in and around Flanders. The lords of Edingen (Hainaut), Zomergem (Flanders), and Deinze (Flanders) reached compromises with the parishes under their jurisdiction. The inheritance tax – in essence a variable right; a subject had to die before the seigneurial officer could claim the due payment – was thereby replaced by either a fixed annual sum or a large unique redemption paid by the entire community.Footnote 109 Such a deal was advantageous for all parties involved. The lord received a reliable form of income, and his receiver was rid of the time-consuming work which inheritance taxes entailed. The peasants in turn were freed of the humiliating practice of giving up a significant heirloom after the passing of a relative and of the mental concerns coupled with succession right planning (and the weighing up of strategies of tax evasion). Most importantly, the tax pressure on peasants reduced or changed considerably: the uncertain timing of meilleur cattel was replaced by a single buy-out, or a recurrent light tax, which allowed for better financial planning. To achieve such compromises, lords and subjects had to negotiate intensively. The image delivered by such case studies sheds a different light on the concept of ‘pervasive lordship’. The lord was pervasive in the sense that he could negotiate from his seigneurial claim to surplus extraction, thus successfully receiving payment, albeit in a different form. As a consequence however, the further pervasiveness of the right in question was forfeited. Concurrently, peasants were equally successful in using whatever agency they had to renegotiate the terms, conditions, and even fiscal pressure of certain seigneurial rights.

Clandestine resistance

As subjects and as a community, villagers and farmers generally knew very well who was colouring outside the lines of the law. So long as the transgressors aided the community however, be it by selling or giving poached game to peers or by hushing up the fraud of ones’ neighbours, the mutual benefits and understanding among subjects was maintained.Footnote 110 Lords evidently deemed fraudulent practices illegal. As the aggrieved party, the seigneur and his officers considered transgressions of surplus extraction rights as infringements on their ‘justice’. Perpetrators such as frauds had to be detected, exposed, and prosecuted. This dichotomy provided the basis of the cat-and-mouse game portrayed in every lordship during the ancien regime. Wickham rightfully discerns the peasants’ position and their advantage as grounded residents, in the sense that they knew the environment best. Their grasp and knowledge on and of the surrounding farms, rivers, forests, and people was far more profound than that of its lordly possessor and administrator. This meant that peasants knew whichever opportunities available to nibble some of the lords’ claimed surplus away. To which extent the reward was worth its enticed risk, seigneurial subjects could consider for themselves. This last section delves deeper into such opportunistic strategies, with a careful assessment of their frequency and the appearance of clandestine peasant strategies in the sources.Footnote 111

The elephant in the room is of course the concept of dark numbers and the methodological hindrances it imposes. Since tax evasion was illegal, and lords possessed the authority to prosecute and fine perpetrators, we have records on such infractions. Even the lowest forms of lordship carried the inherent potency to safeguard those seigneurial rights the lord did possess, and the power to punish possible encroachments.Footnote 112 These documents entail the evidence on the crime and/or the stipulation of the penalty and/or fines. Within the county of Flanders, we discern such traces in seigneurial accounts, court cases, charters and ‘doorgaande waarheden’ (local recurrent questionnaires, whereby the entire village was summoned before the church, square or inn to report about infractions since the last hearing), to name a few.Footnote 113 Obviously, these sources provide a distorted image of the historical reality, since they solely record those infractions suffering an unlucky discovery. The ironic consequence is that our knowledge of such clandestine forms of resistance is shaped by failed attempts, which led to lawsuits, fines or legal measures to prevent or discourage further infractions. Calculating how far seigneurial rights and surplus extraction were conceded or escaped remains a risky endeavour, but a necessary projection nonetheless.

Perhaps the least extreme form of peasant resistance was idleness. Inaction could very well be a form of protest. It may not seem like a spectacular strategy, but it was easy and effective. Not doing anything may be interpreted in two ways: withholding information (not telling) and not performing mandatory action (not doing). Both inactions were reprimandable and could involve personal and/or another’s gain or detriment. An obvious example is concealing one’s due rents or taxes. Chances at success had an inverse relation with the quality of seigneurial administration: the poorer the documentation and memory of seigneurial dues, the higher the likelihood of the peasant’s evasion attempt to succeed. Relatively many examples survive of lordly receivers complaining about aporia and chaotic administrations, especially following periods of crisis such as wars and plagues. When enough peasants kept their mouths shut, officers could suffer great troubles reconstructing which rents weighed on which persons and lands. When Pierre de Goux, chancellor to the duke of Burgundy, bought the Flemish seigneurie of Denderwindeke, for example, he complained about this problematic deadlock. At his wits’ end, he wrote a request to the Burgundian duke (as acting count), who in turn ordered the officers of the Council of Flanders to enforce those inhabitants of Denderwindeke to acknowledge and pay their due rents. De Goux shortly after ordered the composition of a terrier. Be that as it may, even this powerful chancellor – and much less pervasive lords – suffered some temporary or permanent losses of income because subjects simply remained silent about their rents.Footnote 114

Only when methods of withholding, feigned compliance and everything in between failed, subjects resorted to an outright uprising. Though while these forms of resistance obviously fell outside of the law, they were seldomly tolerated. Revolts thus differ from extrajustice. Uprisings happened outside of the legal framework, along with more or less violent struggles and repression. Charters describing the spectacular circumstances and consequences of subject resistance usually testify of the special character of the incident, whereby extraordinary problems required extraordinary solutions. While the study of these conflicts has proven its merits, they should be nuanced and placed within the correct context. Revolts were unique outbursts, often last resorts for a peasantry that felt unheard, powerless, and desperate. One could argue that lords suffering such rare uprisings may have been too pervasive, pushing their subjects over the brink of the tolerable load of burdens, or as Kula put it, having exceeded the social limit for too long.Footnote 115

Conclusion

The socioeconomic and political developments of the 14th century marked the decline of seigneurial lordship in Flanders. While the power of local lords had been contested for longer – and by a multitude of adversaries such as the count, cities, and clerical institutions – the events following the Black Death implied a point of no return. Demographic crises indirectly empowered the surviving rural population. The Council of Flanders symbolized the growing power of the count and his central institutions, curtailing the jurisdiction and fiscal claims of local lords. Since the 13th century, outburghership had been an important medium for cities to control their hinterland and thwart the influence of surrounding lordships on the peasantry. Despite their lessened power, lordships endured until 1795. Outburghership also persisted as an affordable and accessible counterbalance to local seigneurialism. From the 15th century onward however, the established power relation between cities, count, and lords never necessitated the exorbitant urban subscription numbers from before. This went hand in hand with a declining economic and political importance of Flanders’ largest towns. Outburghership retained its use as defence mechanism for seigneurial subjects, but since 1540 the former possibilities of liberal and broad interpretation of its freedoms by both city courts as local peasantries were strictly curtailed. The centralizing efforts of Burgundian and Habsburg rulers had reduced outburghership from a creatively interpretable status claiming exemption for taxes and jurisdictions on several levels during the middle ages, to merely an immunity for certain seigneurial rights to inheritance and justice. Furthermore, the newly accomplished political equilibrium left more room for pragmatic forms of negotiation or ‘infrajustice’. The agreements struck about arrangements of ‘meilleur cattel’ in Edingen, Zomergem, and Deinze are good examples of local communities negotiating and settling disagreements with their lords, without a direct need for external interference.

What this article has shown, through a comparative and broad analysis of outburghership of the county of Flanders, is that even at its peak of power, external citizenship never dominated the entire province, nor did it provide full protection or immunity for lordship. Even being an outburgher was never a guarantee for success in defying seigneurial claims. While citizenship and its privileges remained an important part of the country dweller’s means of resistance until 1795, day-to-day small acts of unruliness or (re)negotiation outweighed the antagonistic conflicts and lawsuits. Historiography has dedicated disproportionate attention to exceptional disagreements between lords and subjects. These were important, obviously, but need to be put into perspective. Whomever wants to discern a rebelling countryside has to look at outburgher lists and lawsuits indeed. Other rebels can be found in seigneurial accounts and bailiff accounts. Entries and notes on rents gone dark, worthless chicken rents delivered or poachers fined hint at dark numbers of undetected, successful tax evasion practices.

Acknowledgements

I wholeheartedly thank Thijs Lambrecht and Frederik Buylaert for providing a research trail on lordship and outburghership, which eventually led to this publication. Several preliminary versions of this text were intensively discussed and corrected by members of the Brain 2.0 project LORD and the GOA project ‘Lordship and Agrarian Capitalism in the Low Countries, c. 1350-1650’. Every suggestion made by colleagues during overtimed meetings - sweetened by cake - improved this paper, for which I am most grateful. The reviewer of this article helped a great deal in improving the focus of this text. Finally I would like to thank the editors of Rural History for their swift and kind help along the publishing process. Even in times of AI technology can falter, which makes a warm human intervention most welcome and appreciated.

Archival sources

Bailiff account of the lord of Avelgem, General State Archives Brussels, TBO 283, L722/5. 1545–’46, f° 22v-23r.

Bailiff account of the lord of Avelgem (and Heestert), General State Archives Brussels, TBO 283, L735/1. 1651–’57, f° 8v-9r.

Archives of the Diocese of Ghent and Sint-Baafs Abbey, State Archives Ghent, series B, 2493.

Archives of the Diocese of Ghent and Sint-Baafs Abbey, State Archives Ghent, Series K, K10713.

Seigneurial account Avelgem, General State Archives Brussels, TBO 283, L684/7. 1473–’74, f° 5r-v.

Seigneurial account Avelgem, General State Archives Brussels, TBO 283, L722/7. 1473–’74, f° 19r.

Seigneurial account Avelgem, General State Archives Brussels, TBO 283, L690/1. 1602–’03.

Seigneurial account Avelgem, General State Archives Brussels, TBO 283, L 700/2. 1655–’56.

Seigneurial account Avelgem, General State Archives Brussels, TBO 283, L 701/5. 1662–’63.

Seigneurial account Avelgem, General State Archives Brussels, TBO 283, L 701/10. 1665–’66.

Seigneurial account Avelgem, General State Archives Brussels, TBO 283, L707. 1732, f° 19v.

Seigneurial account Avelgem, General State Archives Brussels, TBO 283, L715/1. 1776, f° 42v.