Introduction

Ladybird Books, at their apogee in the third quarter of the twentieth century, were an influential British cultural institution occupying a unique place among children’s publishers.Footnote 1 By the time of the company’s centenary in 2015, almost 100 million copies of its Key Words reading scheme had been sold, and many millions more of its other publications.Footnote 2 For the best part of three decades, Ladybird’s editors, authors and illustrators spoke to the imaginations and interests of their readers with remarkable success, reflecting and shaping, although not always unproblematically, the identities, hopes and values of generations of British children, parents, carers and teachers. Investigating the Ladybird phenomenon therefore has the potential to offer revealing insights into central aspects of British cultural and social history in the postwar period and it is very surprising that so little research has yet been undertaken. The most substantial scholarly publication hitherto is Johnson and Alderson’s The Ladybird Story (2014), an indispensable introduction to the firm’s commercial and publishing history. But in the space available, Johnson and Alderson cannot delve deeply into the books themselves, given that 646 titles were published in 63 series between 1940 and 1980 alone, still less explore what Ladybird Books can tell us about the wider cultural currents that shaped them and to which they made such an important contribution.Footnote 3 Other than this, there is Lawrence Zeegen’s Ladybird by Design, published by the firm itself in 2015. But while this is informative and beautifully produced, it is a celebration of Ladybird’s design and typographical achievements rather than a critical history.Footnote 4 One reason for the paucity of research on Ladybird may be that much of the archival record is now in private hands, but there are some business records at the Record Office for Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland, while the Museum of English Rural Life has a rich collection of Ladybird artwork. Some of Ladybird’s authors and illustrators, such as Derek McCulloch (the BBC’s ‘Uncle Mac’) and the artist Rowland Hilder, were well-known figures whose footsteps are readily traceable through the public records and, above all, there is the vast resource of the Ladybird books themselves. So there is ample scope for the extensive research that the company’s cultural significance undoubtedly warrants.

The present article focuses on just four Ladybird publications: What to Look For in Winter (1959), What to Look For in Summer (1960), What to Look For in Autumn (1960) and What to Look For in Spring (1961). These form an unofficial mini-series within the 25-title Series 536 (‘Nature’), which ran from 1953 to 1979.Footnote 5 In restricting this study to such a seemingly narrow compass, I aim to demonstrate the rich rewards close analysis of Ladybird texts can offer cultural historians and to examine the ways the words and images of these books are informed by discourses linking nature, farming, the rural landscape, national identity, tradition and modernisation.

A crucial element of Ladybird’s popularity and commercial success in the mid-twentieth century was the standardisation of the format and design of their books. This allowed the company to achieve exceptional brand recognition combined with low production costs and highly competitive pricing (for thirty years, Ladybird books were sold at a fixed price of 2s 6d). The iconic 56-page pocket-sized format, introduced in 1940 in response to wartime paper shortages, allowed the whole book to be printed on a single sheet of 40” × 30” paper.Footnote 6 The Ladybird logo, restyled in 1961 in a cleaner, more eye-catching design, further strengthened brand identity and came to be perceived as a guarantee of quality as the firm’s reputation for informative educational texts grew.Footnote 7 Perhaps the most critical element of standardisation, however, was the highly effective relationship between text and illustrations that Ladybird’s pocket-sized format facilitated. The verso page always consisted of simple, informative text in a clear font with ample white space around it, and the recto page of a good-quality, full-page illustration corresponding to the text to its left. The ‘What to Look For’ mini-series was no different to any of Ladybird’s other pocket-sized books in these respects. It was also typical in that Douglas Keen, Ladybird’s inspired commissioning editor, managed to secure the services of an accomplished writer with genuine knowledge of the subject to write the text, and a capable artist for the illustrations. The author in this case was Elliot Lovegood Grant Watson, who was not only a prolific writer and novelist but had graduated with first-class honours in natural sciences from Cambridge in 1909 and subsequently undertaken laboratory-based biological research.Footnote 8 The illustrator was Charles Tunnicliffe RA, perhaps twentieth-century Britain’s most widely admired wildlife artist (and probably the most distinguished of Ladybird’s many fine illustrators).Footnote 9 Both men were devotees of the English countryside, and had worked with each other previously, although Tunnicliffe, brought up on a farm, perhaps identified more closely with agriculture while Grant Watson’s scientific interest in nature ran alongside a sense of its psychological and spiritual significance.Footnote 10 These influences can be traced in varying degrees in the ‘What to Look For’ books. However, behind them we should also perceive Keen’s inclinations and commitments. It was Keen who, after returning to the company following war work in 1946, persuaded the directors that the company’s future lay in children’s publishing rather than the motor and hosiery trade catalogues that had been its interwar mainstay. He had done so by writing a mock-up children’s book on British Birds and their Nests, with illustrations by his wife and mother-in-law.Footnote 11 It was undoubtedly in part due to Keen’s influence that natural history featured so prominently in Ladybird’s catalogue between his appointment as director in 1957 and his retirement in 1973.Footnote 12

The trope of the four seasons on which the ‘What to Look For’ books was based is probably as old as literature itself. Seasonal writing features prominently in the English literary tradition, with much-anthologised contributions by Chaucer, Spenser, Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Keats, Hardy and other canonical poets. The most notable literary reference point, however, was James Thomson’s The Seasons (1726–46), one of the most celebrated and influential poems in the English language. Since the ‘What to Look For’ books were written in the first instance to inform children about natural history, it is hardly surprising that they do not overtly invoke Thomson but his work may nevertheless consciously or otherwise have informed Grant Watson and perhaps Tunnicliffe’s approach to the subject. Thomson’s poem was undergirded by a conviction that the seasons were divinely ordained, ultimately conducive to man’s good and proof of God’s benevolence and power. The ‘What to Look For’ books eschew Thomson’s overt moralising but exude an equally calm, assured conviction that the seasons and the cyclical processes dependent on them form a coherent, orderly, self-sustaining and in toto benign natural order. The difference is that Thomson’s God has been replaced by an unspecified principle of order within nature itself, no doubt informed in part by Darwin’s theory of natural selection, in which Grant Watson had been steeped since childhood, but perhaps more by the spiritual awe that in Grant Watson’s case lurked behind this.Footnote 13 Tunnicliffe was a more reticent man, disinclined to trumpet his convictions, but the depth of his attachment to the English countryside and rural tradition is beyond doubt, while the superb glow of many of his bird, animal and landscape illustrations speaks for itself.Footnote 14

Other and quite possibly stronger influences on the ‘What to Look For’ books may have been the long tradition of calendars, almanacs and seasonal lore in English popular culture and, at a more refined level, the non-fiction genre of rural essays and commentary examined by W. J. Keith in The Rural Tradition, exemplified by writers like White, Mitford, Cobbett, Jefferies, Hudson and Sturt.Footnote 15 Albeit in quite different ways, both traditions were deeply imbued with seasonality and concerned with minute observation of its manifestations in changing flora, fauna and weather patterns. Grant Watson and Tunnicliffe were well versed in these literatures – Tunnicliffe, for example, had illustrated Jefferie’s Wild Life in a Southern County for Lutterworth Press in 1949.Footnote 16 However, it is the ways the ‘What to Look For’ books are in dialogue with contemporary agrarian and ruralist discourses that is of most interest from a cultural history perspective. Four such discourses pervade the series. Firstly, the implication that the countryside is fundamental to English national identity. This had become almost a cliché since 1918, such that the Scott Report of 1942, a compendium of contemporary attitudes to the countryside, could approvingly quote in its introduction H. G. Wells’s assertion that ‘There is no countryside like the English countryside’ and follow it up with G. M. Trevelyan’s claim that ‘without natural beauty the English people will perish in the spiritual sense’.Footnote 17 This discourse has been construed as conservative and backwards-looking (for example by Wiener, Howkins and Wright) but more recent scholarship, by Matless and Readman among others, has tended to emphasise the plurality of constructions of Englishness in relation to landscape and the modernising character of some of these.Footnote 18 What is not in doubt is how strong the nexus between landscape and English national identity had become by the mid-twentieth century, and the impetus this gave to preservationist legislation such as the decisive 1947 Town and Country Planning Act. Through endorsing and amplifying the perceived links between national identity and the rural landscape, the ‘What to Look For’ books reinforced the preservationist dispensation established by the 1947 Act, with its emphasis on urban containment and the retention of land in agricultural use. This, as Newby argued in his excoriating Green and Pleasant Land? was neither socially nor politically neutral.Footnote 19

A second discourse featuring prominently in the ‘What to Look For’ books concerns the relationship between farming, nature and the rural landscape, which is presented as one of benign mutual interdependence. This construction again echoes one of the central contentions of the majority Scott Report, which sought to impress upon its readers the conviction that: ‘[t]he beauty and pattern of the countryside are the direct result of the cultivation of the soil and there is no antagonism between use and beauty.’Footnote 20 The Report asserted that much agricultural land had gone out of cultivation between the wars due to lack of government support for farming, and that this had had deleterious effects on the landscape. Hence the argument that the rural landscape could only be preserved through maintaining agriculture had the very clear and direct political implication that farming should be supported by the state, through subsidies, tariff barriers or both. This was implemented in the 1947 Agriculture Act, which was intended to complement the Town and Country Planning Act of the same year and which ushered in as major a change in the relationship between the state and agriculture as the planning act did between the state and land use.Footnote 21 Again, therefore, Grant Watson and Tunnicliffe’s representation of farming, nature and landscape as mutually interdependent reinforced the existing agrarian political settlement, one that, as S. R. Dennison had insisted in his trenchant Minority Report to the Scott Committee, was by no means uncontroversial or even perhaps sustainable.Footnote 22

One of Dennison’s claims was that extensive mechanisation was necessary to maintain competitiveness and raise living standards in British agriculture, but that this would be incompatible with retaining a large agricultural workforce.Footnote 23 Once again, this was a perspective Grant Watson and Tunnicliffe chose to ignore. By 1959, when Winter was published, the most rapid and perhaps fundamental period of change British agriculture had ever experienced was already well advanced. In the late 1930s there were still 650,000 farm horses in Britain, constituting half of British agriculture’s total draught power and performing two thirds of the work, but by 1955 horses had been virtually eliminated.Footnote 24 The number of combine harvesters had risen from 940 in 1942 to 67,000 in 1966 while wheat yields rose from about two tonnes per hectare in 1952 to eight tonnes per hectare in 1986.Footnote 25 Within a few years, a centuries-old horse-based agricultural regime, with its associated crafts and skills such as blacksmithing, saddlery and wheelwrighting, had been swept away and replaced by something quite different. It was a concern to preserve the material culture of this vanquished agricultural ancien régime that led to the foundation of the Museum of English Rural Life in 1951.Footnote 26 But although mechanisation does feature in the ‘What to Look For’ books, in some interesting ways, there are only fleeting hints of any awareness of the troubling possibility that it might threaten the continuity of the agricultural landscape and of farming tradition, or the supposed symbiosis between agriculture and nature.

The fourth discourse prominent in the ‘What to Look For’ books is the link between people, farming, nature and the rural landscape. Representations of the English countryside, especially those influenced by the landscape painting tradition inaugurated by Gainsborough, have often been critiqued as ‘landscapes without figures’. It has been argued that the dominance of picturesque modes of apprehension has meant that artists and tourists have regarded rural landscapes from an almost purely visual perspective, experiencing the countryside as an aesthetic object rather than as a social environment within which people live and work. Even an artist as concerned with social relationships as Constable could, as Barrell demonstrates, end up more-or-less painting the people of the countryside out of his landscapes.Footnote 27 Grant Watson and Tunnicliffe reject this way of seeing. Rural workers feature in many of the illustrations to the ‘What to Look For’ mini-series, and their activities and skills are explained in the accompanying texts. However, the illustrations especially tend to subsume them unproblematically into the landscape, just as Tunnicliffe does the wild and domestic animals he paints with such care. Whether naturalising rural workers (and, hence, the often profoundly unjust social relations in which they are embedded) is preferable to denying their existence by failing to represent them altogether is perhaps an open question.

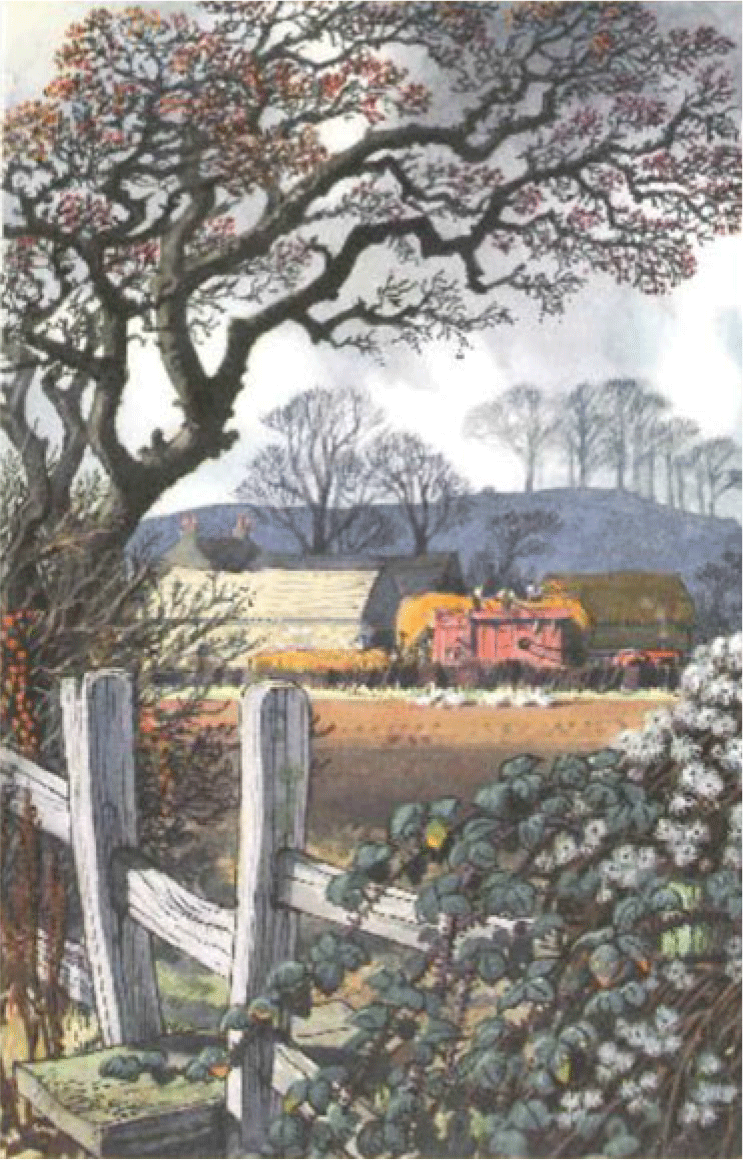

Figure 1. ‘The stile’. Illustration from What To Look For In Winter by Charles Frederick Tunnicliffe © Ladybird Books Ltd (1959).

Winter

To elucidate these points, I now turn to a close analysis of some of the most pertinent page spreads from the ‘What to Look For’ books, starting with Winter, the first to be published. Each book takes a diachronic approach to the season it describes, following it through from its inception to its end. The close of one book therefore leads seamlessly into the opening of the successive one, reinforcing the cyclical continuity the books attribute not only to nature but also to the rural life discursively embedded in it. One of the first spreads in Winter shows geese feeding on stubble and ploughland (Figure 1). Tunnicliffe’s composition underscores the ostensible unity between people and nature. The farmstead is framed within the protective embrace of what seems to be an oak, while a sheltering, tree-planted hill and trailing fronds of Old Man’s Beard complete nature’s encirclement of the human. The prominent stile and the geese contribute to the merging of the human and the natural. The stile is constructed, but out of natural materials; the geese are domestic animals so with affinities to both the human and the natural. Furthermore, they are eating grain, which has been spilt as a by-product of human labour. The other striking element in the composition is the careful balancing of tradition and modernity. The focus of attention is the threshing machine, with the diminutive figures of the labourers upon it. Although threshing machines were a devastatingly disruptive technology when they were introduced in the first half of the nineteenth century, and were, indeed, one of the leading causes of the Captain Swing protests of 1830–1, by 1959 they represented tradition and continuity rather than rupture, so much so that they were soon to become a staple feature of vintage steam fairs. However, the threshing machine is powered not by a steam engine but by a tractor, indicative of innovation and modernisation. Yet the tractor is sufficiently inconspicuous that it does not threaten the overall harmony of the scene.Footnote 28

We are offered a similar union of the human and the natural, mediated as before through farming, in another spread from Winter. Here, two farmworkers (one perhaps a farmer) are providing winter fodder for cattle.Footnote 29 Compositionally, the human is again encompassed by the natural: in this case, the men are framed between stems of cow parsley. Grant Watson points out that the men and cattle are both in their winter coats, as if the men grew their coats like animals. As with the previous image, mechanisation is intrinsic to the scene, yet it is soft-pedalled. The bright red tractor, the most potentially discordant element, is mainly hidden behind the blue trailer and faces unthreateningly away from us. Not only is blue often perceived as a more natural colour than red, but the trailer is loaded with kale, further softening the divide between the natural and the artificial.Footnote 30

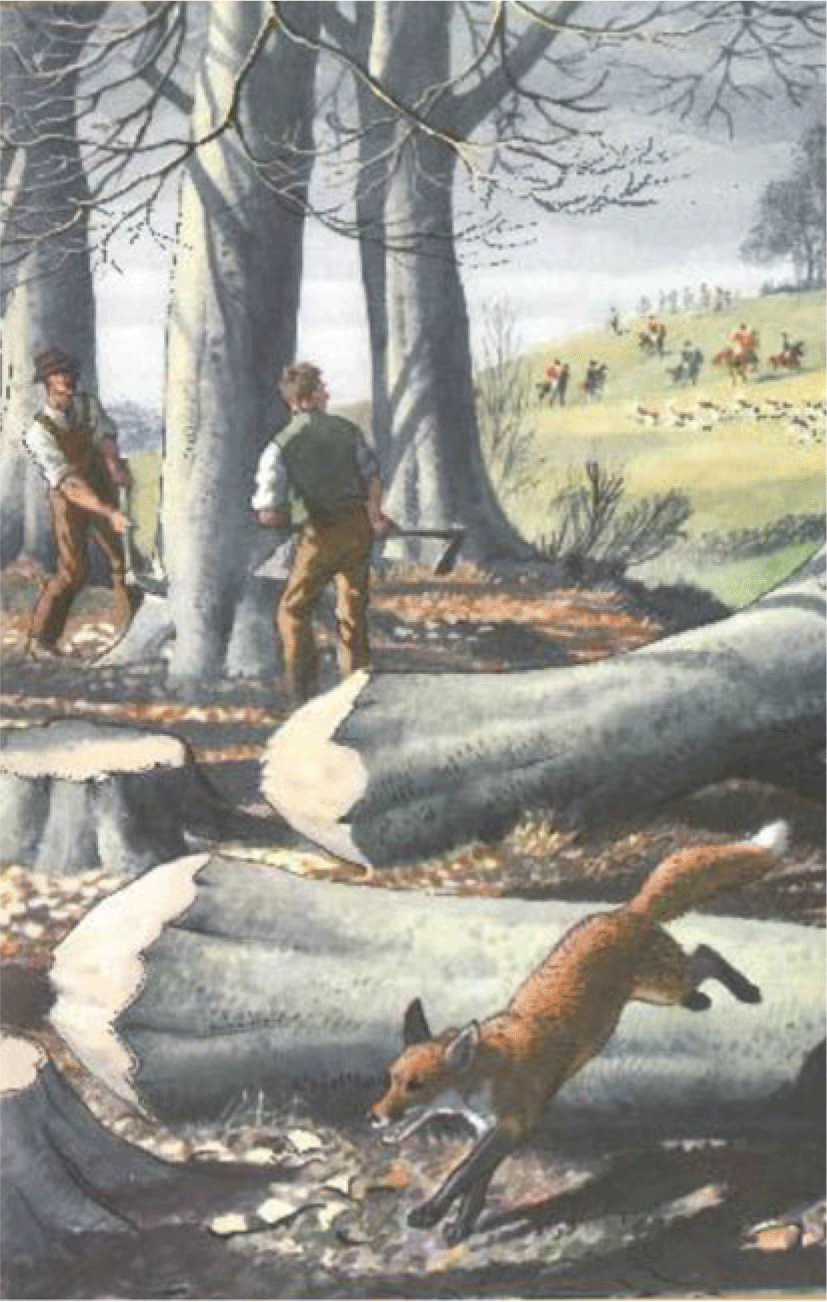

Figure 2. ‘The fox hunt’. Illustration from What To Look For In Winter by Charles Frederick Tunnicliffe © Ladybird Books Ltd (1959).

There were obvious aspects of rural life that it was less easy to represent in this way, as benign for all concerned. A striking instance is provided by Winter’s foxhunting scene (Figure 2). Yet Grant Watson’s text and Tunnicliffe’s painting work together to head off the apparent contradiction. As we see the fox bounding out of the picture to safety, we are assured that ‘he’ will ‘probably live to raid the farmer’s hen roost yet again’. An equivalence is created between the fox and the hunters: just as they hunt the fox, so it hunts their hens. Moreover, this conflict is supposedly on relatively equal terms. Similarly, image and text work together to ground hunting in rural society. The two woodcutters look up to watch the hunt streaming down the hill towards them, in a gesture open to a number of interpretations, but the text insists that ‘like all countrymen they enjoy the sight’. Here we have both a unitary, monolithic definition of rural society (one that excludes, for example, the members of the League Against Cruel Sports who bought land on Exmoor to provide hunted deer with refuges), and hunting presented as natural because the fox itself is a hunter, so in hunting the fox countrymen are only behaving like nature itself.Footnote 31

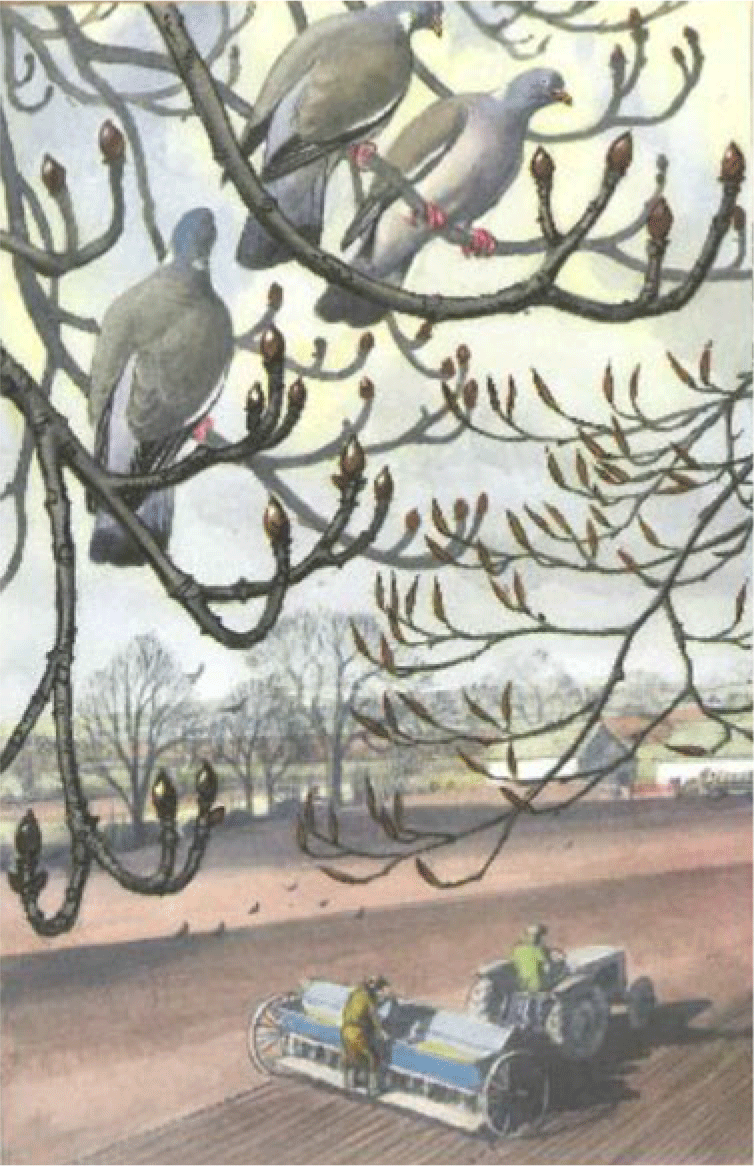

Figure 3. ‘The seed drill’. Illustration from What To Look For In Winter by Charles Frederick Tunnicliffe © Ladybird Books Ltd (1959).

Figure 4. ‘The seed drill’. Illustration from What To Look For In Spring by Charles Frederick Tunnicliffe © Ladybird Books Ltd (1961).

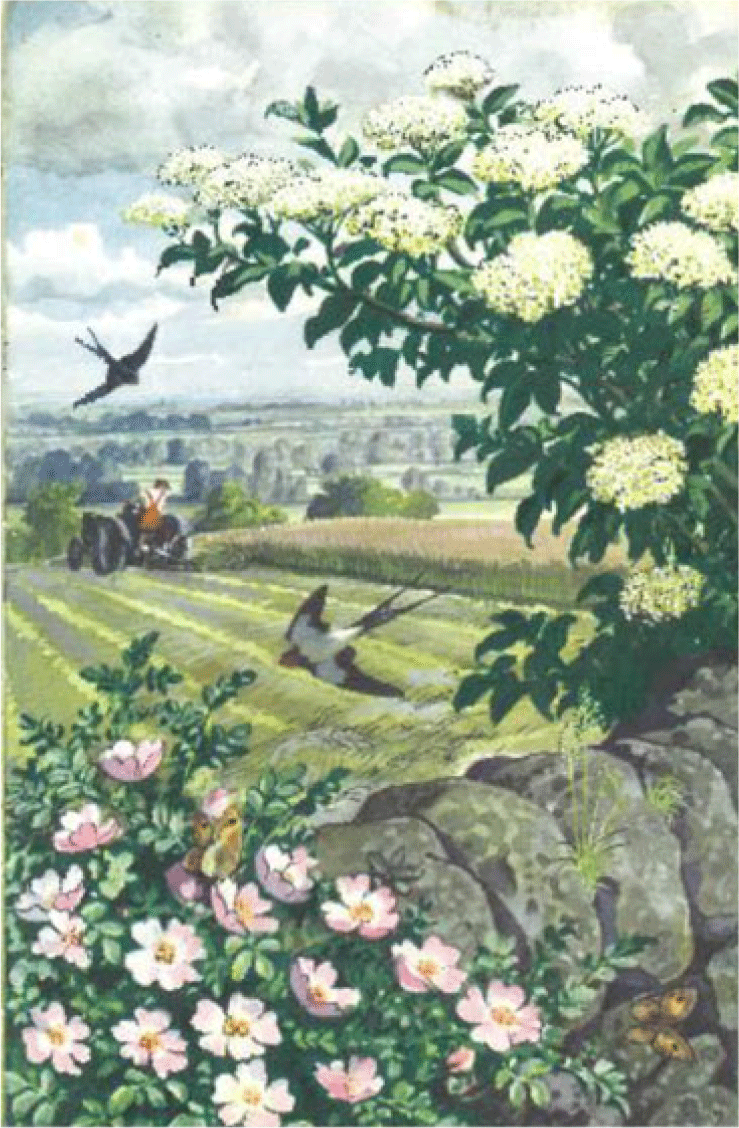

Figure 5. ‘The dry stone wall’ (cover). Illustration from What To Look For In Summer by Charles Frederick Tunnicliffe © Ladybird Books Ltd (1960).

The last spread I will consider from Winter shows a seed drill at work (Figure 3). Like many of Tunnicliffe’s accomplished illustrations, this is a striking and effective composition (although despite Ladybird’s impressive production standards, the published version lacks the glow of the original artwork now at The Museum of English Rural Life). The unusually high vantage point invites the reader to see the scene from the perspective of the woodpigeons perched in the horse chestnut. This reversal of perspective, such that ‘nature’ appears to be looking at ‘us’ also features in several of Tunnicliffe’s other ‘What to Look For’ paintings. There is a hint of ecological radicalism here in the anthropic decentring. Ultimately any such decentring inevitably involves a form of ventriloquism, since it is necessarily the human viewer looking at the woodpigeons looking at the farmworkers (who have their backs turned and may be unaware that they are being observed). Nevertheless, the quiet radicalism Tunnicliffe and Grant Watson achieve here should not be underrated. The ‘What to Look For’ mini-series sustains a careful balance throughout between the natural (ecological) and human (agricultural), with neither allowed to predominate. Natural processes are literally foregrounded and presented as having an intrinsic value of their own irrespective of human affairs but at the same time farming is shown as a legitimate and necessary activity in a continuous ongoing dialectical relationship with nature on a give-and-take basis of rough equality. Grant Watson’s text explains that while farmers shoot woodpigeons, ‘they are quite aware of what is happening’ and ‘know just as much about guns as they do about corn’. Yet from an animal rights rather than ecological perspective this equivalence does not ring true: the consequences to the woodpigeons of being shot are quite out of proportion to the consequences of a reduced harvest for farmers.Footnote 32

These tensions notwithstanding, Tunnicliffe’s palette and composition work skilfully to assimilate farming, nature and the landscape. The mauve of the woodpigeon’s heads, necks and tails corresponds to that of the sky, the end wall of the barn and, most significantly, to the seed drill and the tractor, while the barn is held within a lattice of beech twigs and merges into the fields and trees that adjoin it.Footnote 33 Again, there is a quiet radicalism here that it would be easy to miss. Although the characterisation of English landscape painting as ‘landscapes without figures’ is questionable, to describe the artistic (including photographic) representation of the modern English countryside as ‘landscapes without tractors’ would be entirely legitimate. There is a startling contrast between the ubiquity of the tractor in the phenomenal landscape and its absence from its representational equivalent. The ‘What to Look For’ books gently but persistently challenge this – tractors and agricultural machinery recur frequently in Tunnicliffe’s illustrations. There was no necessity for this in books whose remit was to draw attention to natural processes but to do so was characteristic of what was perhaps the fundamental reason for Ladybird’s pre-eminence in postwar children’s publishing: the company’s success in riding the wave of modernist optimism while simultaneously evoking a powerful sense of shared community, securely rooted in tradition.

Spring

One of the first spreads in Spring follows seamlessly from this, as it shows what appears to be the identical seed drill (Figure 4). The same careful balancing of modernity and tradition is in evidence, but now Grant Watson’s text seems barely able to contain the contradictions:

The elaborate tilling machine, which can till twelve drills of wheat at a time, is a far-reaching advance on the earlier hand-scattering of seeds. Hand-sowing was a primitive, though skilful, art – but had some virtues; the grains fell thickly, and the plants that sprang from them gave cover to such birds as the corncrake and stone-curlew, both of which are now becoming almost extinct.Footnote 34

Rachel Carson’s grim admonition Silent Spring was only published in 1962, a year after What to Look For in Spring, but Grant Watson was evidently already conscious of the potentially adverse ecological implications of agricultural modernisation.Footnote 35 While his 1961 text continues to celebrate the achievements of technological progress, the harmony between farming and nature now seems open to question, perhaps even a thing of the past. Tunnicliffe’s illustration, however, offers an implicit rebuttal. Black-headed gulls, rooks and lapwings swirl exuberantly round the seed drill, the gulls eating the worms and grubs the drill has exposed in a visual recapitulation of Winter’s theme of benign interdependence. The composition superbly expresses Tunnicliffe’s profound sense of the unity of nature, farming, landscape, history and national identity. The rooks and lapwings towering into the sky echo the tall elms, an iconic feature of the contemporary English landscape. In a signature Tunnicliffe motif, the elms embrace a medieval steeple, paralleling their tall boles. At the base of the elms and the church, discreetly, respectfully but unapologetically, is a tractor.Footnote 36

Summer

The theme of national identity carries across to the front cover of Summer and the text that accompanies the spread from which the cover illustration is taken (Figure 5). Grant Watson asserts that ‘the wild rose, the emblem of our country, has been loved by all generations of English men and women’.Footnote 37 The emphatic gender inclusivity is as characteristic of Ladybird’s determination to speak, or claim to speak, for all as is the uncompromising insistence on a singular national identity, and the apparently quite unselfconscious assumption that this national identity can be unproblematically English in a book published for a British readership. Yet if Grant Watson seems oblivious to the composite nature of the British state, both text and artwork respond to the nexus between national and regional identities. Dry stone walls of the kind over which the roses are shown as growing had by this time become feted markers of specific English regional identities, especially in upland areas such as the Cotswolds, Yorkshire Dales and Lake District.Footnote 38 The suggestion here, as Paul Readman has recently argued, is that distinctive regional identities fed into rather than competed with a larger sense of national identity.Footnote 39 As Grant Watson observes, ‘[t]he stone wall suggests a northern county rather than a southern one, but the June air is the same everywhere.’Footnote 40 Ladybird’s attempt to construct an inclusive nationalism was as concerned to encompass northern regional identities, which in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had often been marginalised by the dominance of ‘south country’ landscape representations, as it was to reach out to female citizens, although in both cases there is scope to question how far this reaching out constituted a genuine acceptance of diversity and how far it should be construed as abrogation to a project seeking to mould a hegemonic national identity.

The version of national identity Ladybird sought to construct in the postwar period was informed by developing conceptions of geographic citizenship. Matless has explored the ethics of close attention to nature developed, for example, in the bestselling ‘I-Spy’ books and in spatial practices such as the construction and walking of nature trails.Footnote 41 The ‘What to Look For’ books endorse this moral geography. The text accompanying the wild rose spread encourages young readers to walk among swathes of cut hay in the hope of finding, ‘if you are lucky’, tiger-moths, cream-spot tiger-moths, ghost swifts, slowworms and long and short-tailed field mice. Having found some of the ‘treasures’ the fields have to offer, readers are enjoined to ‘come back to the stone wall and smell the delicate scent of the roses, and the more pungent sweetness of the elderflowers’.Footnote 42 Text and illustration work together here to break down the barrier between representation and reality, since it is only in their imaginations that readers can walk back to the fictional wall and immerse themselves in the scent of the flowers.

Another spread in Summer warrants comment for three reasons.Footnote 43 It shows a cock house sparrow eyeing the nests that house martins are building under the eaves of a farm building, with a labourer constructing a haystack in the background. This reiterates, firstly, the supposedly benign relationship between agriculture and nature: the farm building provides habitat for the house martins and sparrow. Secondly, the text develops the representation of wild animals as knowing, even cunning, putting their relationship with humanity on a putatively level playing field and therefore implicitly justifying practices such as the killing of agricultural pests. Grant Watson tells us that the sparrow ‘is waiting to tell his wife how to get a new house without paying for it’ (that is, by expropriating one of the martins’ nests). Thirdly, the text draws attention to the farm worker forking hay in the background. Again, this is no landscape without figures. However, the farmworker is diminutive, smaller than the birds in the foreground, and like virtually every other human figure in the ‘What to Look For’ books, has his back turned to us so we cannot see his face. This is in part a familiar artistic device intended to draw the viewer into the picture but it also has the effect of de-individualising those represented. The worker is seen in the same glance as the birds and neither text nor illustration make any distinction in the way of seeing.Footnote 44 While there is potentially a positive ecological message in this recognition of a rural taskscape that collapses unsustainable dualistic distinctions between the natural and the human, naturalizing representations of rural labour of this kind have also been critiqued, for example by Barrell, as a means of obscuring the constructed, inherently political and often highly exploitative character of rural social relations.Footnote 45

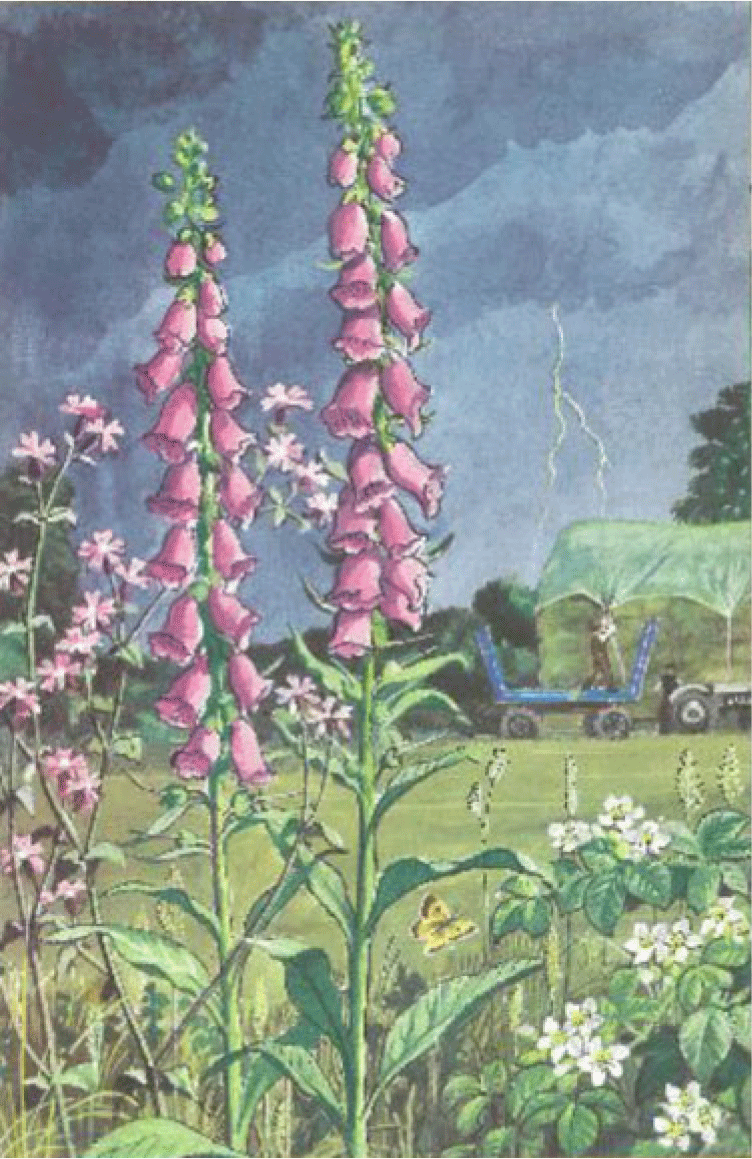

Figure 6. ‘The thunderstorm’. Illustration from What To Look For In Summer by Charles Frederick Tunnicliffe © Ladybird Books Ltd (1960).

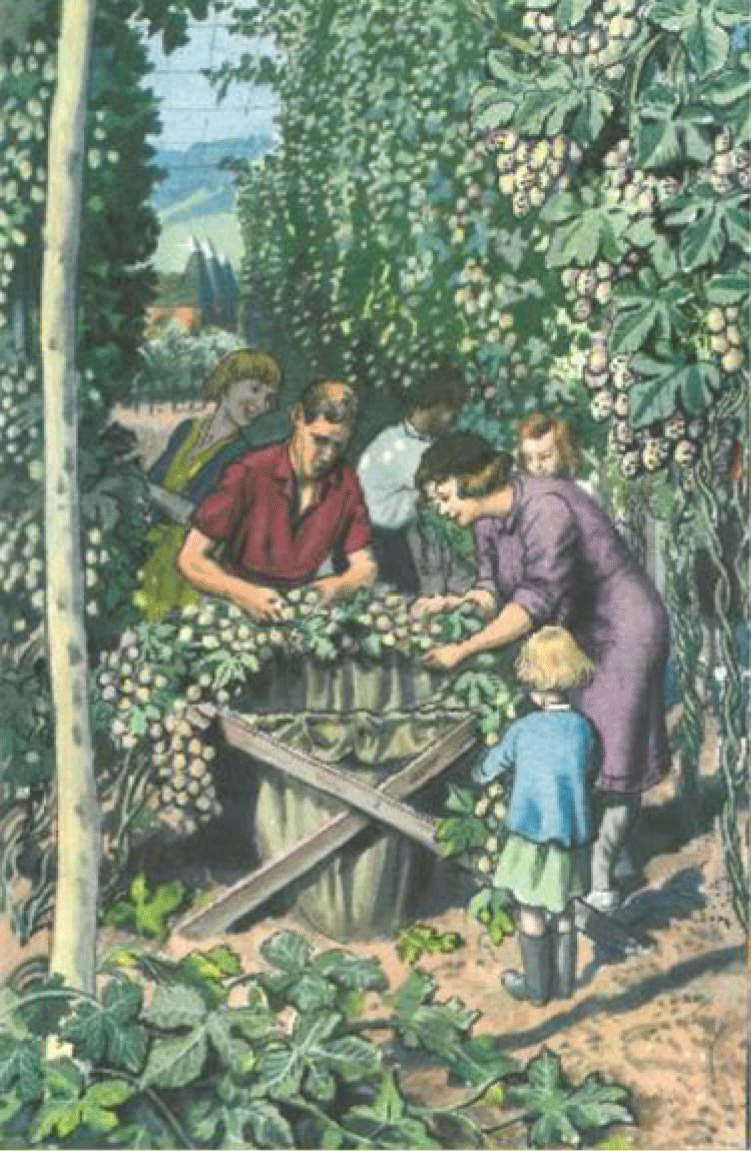

Figure 7. ‘The hop harvest’. Illustration from What To Look For In Autumn by Charles Frederick Tunnicliffe © Ladybird Books Ltd (1960).

This ambiguity is equally present in the one spread from Summer that hints at danger (Figure 6). This shows, in the foreground, two tall, elegant but poisonous foxgloves, and in the background a bolt of lightning descending towards a farmer covering a haystack with a tarpaulin. However, we are assured that he is ‘just in time’ to keep the rain from the newly stacked hay.Footnote 46 The scene is strikingly similar to one in John Schlesinger’s 1967 Far From the Madding Crowd.Footnote 47 In both cases, as in Hardy’s novel from which the film is adapted, danger is contained by traditional agricultural knowledge and skill. In the Ladybird book, the weather also threatens an uncommon butterfly, a clouded yellow that we are told ‘will have to seek shelter if it is not to be beaten down by heavy rain – and possibly drowned’. Grant Watson explains that clouded yellows do not breed in England, migrating from the continent only when weather conditions are favourable. They are, he asserts, ‘always welcome visitors from foreign lands’.Footnote 48

Autumn

A spread from Autumn suggests that this inclusive nationalism may also extend to human immigrants (Figure 7). The context here is hop picking, which for much of the twentieth century brought thousands of urban working-class people, many of them from the East End of London, out into the rural south-east and West Midlands in early autumn. The central figure in Tunnicliffe’s illustration is a black man, possibly Afro-Caribbean.Footnote 49 It would have been tokenistic and arguably even distorting to feature ethnic minorities in scenes intended to represent everyday farming operations given the exiguous numbers of ethnic minority residents and regular workers in the English countryside at this time. Here, however, it is neither, since the areas from which the migrant hop pickers were drawn were ethnically much more diverse. It may be relevant that Grant Watson, who had spent much time travelling in Australia, was noted for his sympathetic and respectful interest in Aboriginal culture, although the text that accompanies Tunnicliffe’s illustration makes no mention of ethnicity.Footnote 50 However, it is probably not accidental that the black worker faces away from us, in contrast to four of the five other figures depicted. This is consistent with the cautious inclusivity of Ladybird’s attitude to citizenship evident throughout the ‘What to Look For’ books and elsewhere in Ladybird’s oeuvre, although the lack of diversity and constraining approach to gender roles in Ladybird’s flagship Key Words reading scheme occasioned sharp criticism in the 1970s.Footnote 51

Other aspects of the hop picking scene require less comment. These are some of the few women workers depicted in the ‘What to Look For’ books – there are others, a few pages later, engaged in potato harvesting – but in a period when women’s agricultural labour had become increasingly restricted to the house, farmyard and non-mechanised harvesting, this was probably realistic.Footnote 52 The figure of the child is poignant, since this is one of very few representations of children in a series intended for child readers. Perhaps in this case the fact that she has her face turned away is an invitation to young female readers to identify with her. However, she is looking attentively down at her work, rather than at the oast houses (another quintessential regional signifier) framed between the hop poles. It is indeed this framing that dominates the image. Gender, age, ethnicity, class and urbanism are held within the hops, which like so much of what is emphasised in the ‘What to Look For’ books are both natural and artificial at the same time.Footnote 53

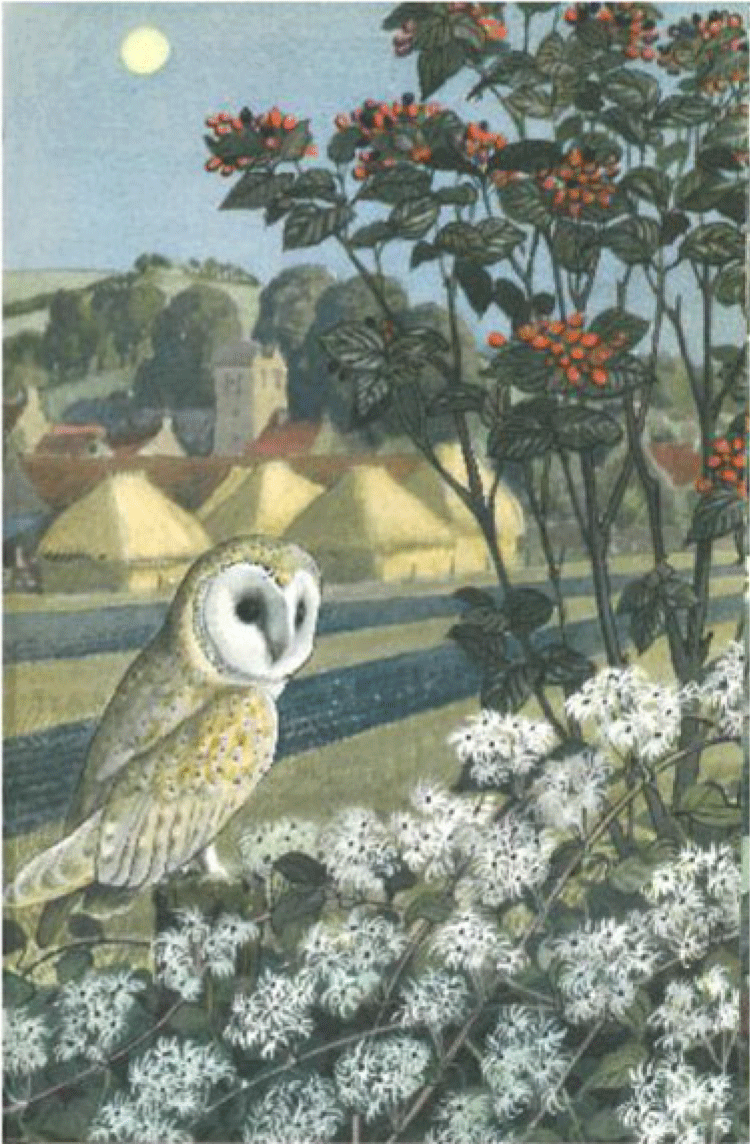

Figure 8. ‘The barn owl’. Illustration from What To Look For In Autumn by Charles Frederick Tunnicliffe © Ladybird Books Ltd (1960).

Among Autumn’s remaining spreads, the three most interesting in relation to the themes of this article are focused respectively on a barn owl, sugar beet harvesting and a shepherd. The barn owl spread draws together many of the key themes and messages of the ‘What to Look For’ books (Figure 8). In view of Tunnicliffe’s deep knowledge of ornithology and mastery of bird painting, it is not surprising that his painting for this spread is one of his finest Ladybird images.Footnote 54 The great white disc of the owl’s face stares towards the viewer, and once again Tunnicliffe makes use of reversed perspective, whereby we look from the natural to the human. The gradations are carefully calculated: in the foreground, the indubitably wild bird; then the field, earth superficially scored into furrows by man; the haystacks, wholly constructed but of natural materials; the houses, whose red-tiled gables echo the haystacks but are of artificial materials; and finally, at the centre of the village, the church, placed visually directly above the owl’s head, as if to symbolise its counterpart – civilisation juxtaposed with wildness. Yet despite these elements of polarity, more important is the continuum, which is achieved mainly through colour: the owl’s wings, the stubble, the stacks, the gable ends and the harvest moon high overhead are almost the same shade of yellow-buff.Footnote 55 This compelling image sums up Tunnicliffe’s vision of harmony between nature, farming, history (of which the church is a powerful signifier, just as it is in the Spring seed drill spread – see Figure 4) and landscape. The implication is that an agriculture rooted in tradition and respectful of nature will become, over time, an organic, enduring part of it. ‘[T]his will go onward the same/Though dynasties pass’, as Hardy wrote in 1915; even then, as the first American tractors arrived to help with the war effort, it was wishful thinking.Footnote 56

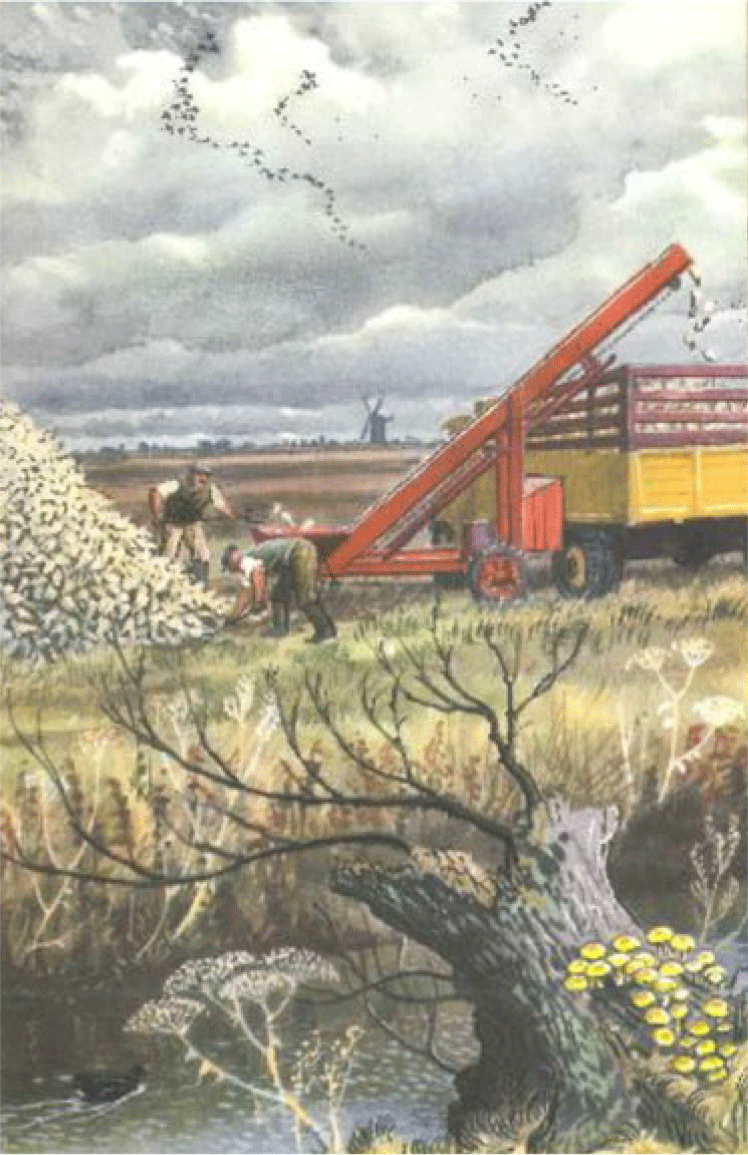

Figure 9. ‘The beet harvest’. Illustration from What To Look For In Autumn by Charles Frederick Tunnicliffe © Ladybird Books Ltd (1960).

As we have seen, however, the ‘What to Look For’ books did not shy away from agricultural mechanisation. The sugar beet spread is an interesting example of how Grant Watson and Tunnicliffe attempt to reconcile seemingly ugly, obtrusive machinery with nature and the landscape (Figure 9). The reader is informed that the large flat fields and few hills of the implicitly unappealing East Anglian landscape allow a ‘wonderful view of the sky’. Even here, history is not absent, as the ‘old-fashioned’ windmill indicates. Once again, Tunnicliffe’s composition works to integrate and harmonize nature, farming and the landscape. The harsh, angular triangle of the beet elevator rhymes not only with the beet pile opposite but with the arms of the windmill and the v-shaped skeins of wild geese and, more subtly, the umbellifers growing by the dyke.Footnote 57 It is as if the two men are determined to prove that even the most awkward, unappealing manifestations of agricultural modernity bear a meaningful relationship to nature and the landscape, so cannot be alien to it.

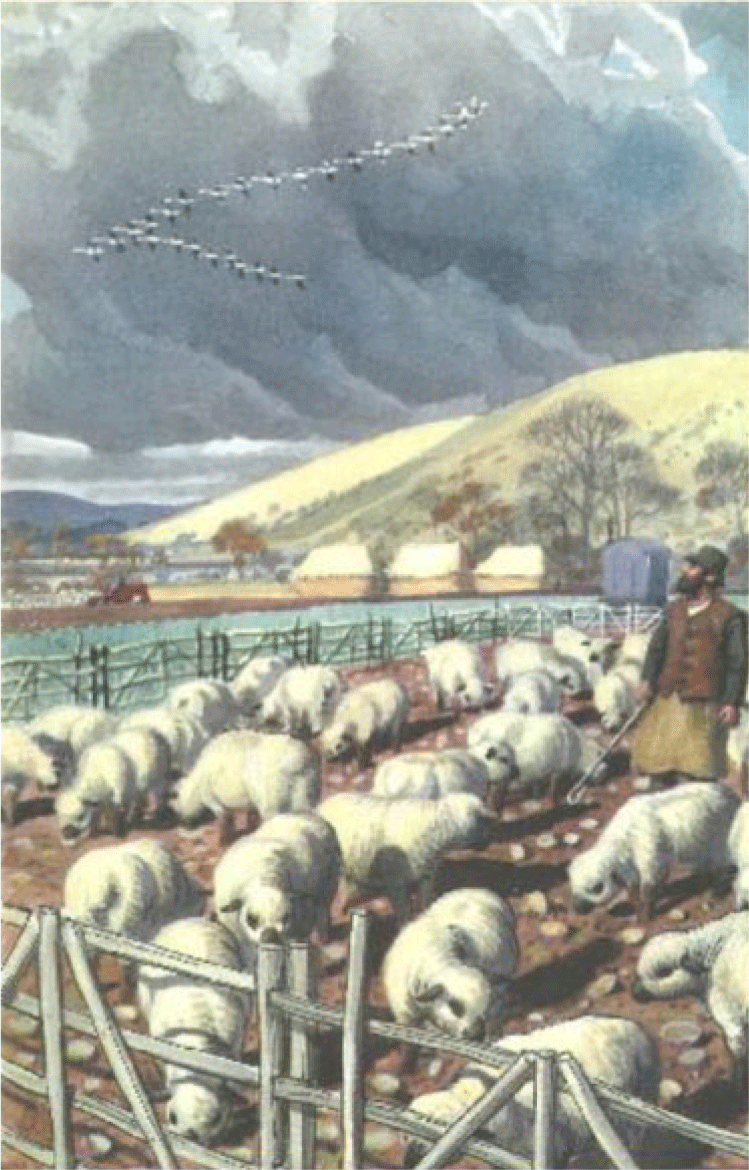

Figure 10. ‘The shepherd’. Illustration from What To Look For In Autumn by Charles Frederick Tunnicliffe © Ladybird Books Ltd (1960).

The final spread to which I would like to draw attention (of many that might have been chosen) reaffirms but also subtly undercuts this perspective. It shows a shepherd who has folded his sheep, which look like one of the traditional down breeds, in a temporary pen (Figure 10). In the background is the shepherd’s mobile hut – this shepherd, unlike most, still lives out with his flock. The bold clean curve of a chalk down rises behind.Footnote 58 These are signs that the shepherd is practising the sheep-corn system, which had been prevalent on the English chalklands in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The purpose was to transfer nutrients from the thin, infertile soils of the upper slopes, which were never ploughed, to the potentially more fertile valley floor and lower slopes. The sheep were pastured on the hill during the day, at least in summer, and folded in the valley overnight, where they dropped and trod in their dung, fertilising the land, which was subsequently ploughed and cropped. After harvest, the sheep might sometimes also be folded in the valleys and fed on roots such as swedes. The system depended on light, portable wooden hurdles, the making of which was a skilled local craft. Sheep-corn therefore bound together geology, landscape, craft skill and regional livestock breeds in a complex agricultural practice. However, by the mid-twentieth century it was in steep decline.Footnote 59 Its rationale was to boost crop production through raising the fertility of arable land but the rise of nitrate fertilisers (the volume of which used by British farmers quintupled between 1945 and 2001) made sheep dung redundant.Footnote 60 The high labour costs of sheep-corn sealed its fate once soil fertility no longer depended on keeping livestock.

Opposite the shepherd, visually on the same level as his head, is a small red tractor. In the established ‘What to Look For’ idiom, it is very definitely present, yet unobtrusively so – in the background, blending visually with the reddish soil, the shepherd’s jacket and the autumnal russet of the trees. But although the tractor is merged into the landscape, it also represents the new technology that was superseding the sheep-corn system. How does the shepherd relate to it? While Grant Watson assures us that he is looking at the skein of migrating whooper swans overhead, as Tunnicliffe has depicted it his gaze seems as much on the tractor below as on the swans above. In the verbal and visual representation of rural landscapes, shepherds are figures freighted with unmatched symbolic charge. This is partly biblical – the good shepherd, for example, as a metaphor for Christ – and partly due to the venerable literary tradition of pastoral, in which shepherds epitomise the benignity and even felicity of rural life. This shepherd, on the penultimate spread of Autumn, partakes of these associations. He is the guardian of rural tradition and sound agricultural practice – Grant Watson assures us that the ewes are ‘in good condition’ – and his gaze, encompassing swans and tractor, integrates farming and nature, modernity and tradition as the ‘What to Look For’ books seek to do throughout. Yet migrating birds always signify departure as well as arrival. Perhaps there is a hint of mournfulness in the shepherd’s glance – could the swans flying away overhead indicate the passing of the sheep-corn system, and the rupturing, through uncontainable modernisation, of the unity between nature and farming that previous spreads have worked so hard to establish?Footnote 61

Conclusion

The ‘What to Look For’ books omitted much. They gave no hint of the ongoing scandal of low wages in agriculture: as research by the Low Pay Unit demonstrated, even by the 1970s agricultural wages remained pitifully low: although in absolute terms they were much higher than a century before, in relative terms the differential with industrial wages had not closed at all.Footnote 62 Grant Watson and Tunnicliffe also passed over in silence the powerlessness of Newby’s ‘deferential worker’, trapped in a dependent, often one-to-one, relationship with his or her employer and usually without the protection of a union.Footnote 63 Nor did they acknowledge the drastic decline, to the point of near demise, in the number of regular, year-round farm workers, and the collapse in their staunch, often nonconformist and sometimes trade unionist culture – what Howkins with some hyperbole denominated ‘the death of rural England’.Footnote 64 Although to the observant reader Tunnicliffe’s illustrations did point to the very limited opportunities for outdoor work for rural women, Grant Watson’s text made no reference whatsoever to this. The ‘What to Look For’ books also evaded or distorted difficult questions about the relationship of humanity to both wild and domestic animals. Factory farms are conspicuous by their absence; wild animals are anthropomorphised by endowing them with a false equivalence in cunning to the human beings who hunt and shoot them.

Above all, the ‘What to Look For’ books ignored what Shoard called the ‘Theft of the Countryside’ – the massive destruction of hedgerows, woodlands, marshes, moors and hay meadows, the pollution of watercourses and the devastation of wildlife through modern agriculture practices, not only mechanisation but also the wholesale application of herbicides, pesticides and chemical fertilisers.Footnote 65 In many respects, the ‘What to Look For’ books were already out of date when they were written, a late expression of a brief moment of equipoise in British agriculture, best captured in the majority Scott Report, when prosperity had returned after decades of depression but before drastic modernisation swept away the fabric of traditional farming practices. Even Ladybird themselves eventually had to recognise elements of this unpalatable reality, issuing a new series, ‘Conservation’ (Series 727) from 1973. The third title in the series was ‘What on Earth Are We doing?’ (1976).Footnote 66 As Zeegen emphasises, what Ladybird Books had offered, at least in their heyday in the 1950s and 1960s, was a ‘utopian vision’ rather than the sober representation of reality it purported to be.Footnote 67

Yet understood as a vision of what the relationship between agriculture, rural society, the natural environment and the landscape could be, the ‘What to Look For’ books had much to recommend them. In a series primarily about wildlife, Grant Watson and Tunnicliffe could have excluded rural labour altogether, but instead they chose to give it a prominent place, avoiding the powerful, damaging representational trope of a ‘landscape without figures’. The two men construed the relationship between national identity and the rural landscape in inclusive, open terms, both with respect to regional identities and ‘welcome visitors from foreign lands’. Above all, the ‘What to Look For’ books offered an ambitious synthesis of the natural and the technological, mediated through an agriculture that was open to the future but firmly rooted in traditional knowledge and skill. Given that the ground was being cut from under the feet of those who, like Grant Watson and Tunnicliffe, clung to this way of seeing, it is unsurprising that cracks show through, most overtly in Grant Watson’s comments on the ecological consequences of the demise of hand sowing. But perhaps the failure of subsequent generations to sustain the optimism of the normative vision given such rich expression in the ‘What to Look For’ books, and to find ways of bringing agricultural practice into closer correspondence to it, is as worthy of comment as the omissions and elisions that allowed author and artist to present this vision as a version of reality in the first place.